There’s no such thing as a tame cougar.

—Robyn Barfoot, curator, Cougar Mountain Zoo

“The owner went into the [African] lions’ cage first, there were maybe three or four of them,” Rick James recalled. “The lions growled and snarled and he really had to pay attention. He used a whip and chair to keep them back. It was scary to watch as a kid—you knew if he glanced away for a second they’d be on top of him.

“After that he’d go into the cougar cage,” James continued. “They were laying in a bunk bed arrangement. As soon as the cougars saw the man they’d roll over on their backs and he’d rub their bellies. Then the cougars would put their front legs and paws around his shoulders and neck and lick his face. They were like big tame pussy cats compared to the lions.”

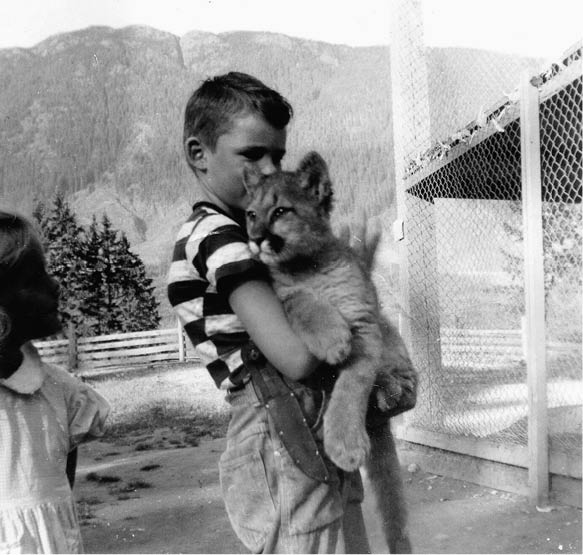

The James family often visited Hertel Zoo when passing through Nanaimo, BC. But what stands out most in Rick James’s mind is the time in 1956 when he was nine years old and got to hold one of the young cougars. “It was heavy, all squirming muscle and gristle. And even as a kitten, so strong and powerful.”

Rick James will never forget holding a five- to six-month-old cougar cub at Hertel Zoo in 1956. But while he struggled to hang on to the squirming animal, it focused its attention on his younger sister, Bonnie. Photo courtesy Rick James

The zoo was popular with many families and Paul Hertel always put on a good show. But tragedy struck in May 1958 when an African lion escaped and killed a young girl playing in the nearby woods. The zoo was closed and Hertel was charged with manslaughter. He wasn’t convicted but the jury recommended British Columbia establish regulations for the operation of private zoos.

Humans have kept wild animals since ancient times. Originally called menageries, early collections belonged to royalty and were primarily for their private use. King Solomon, William the Conqueror and China’s Empress Tanki were all known to keep a variety of large cats, elephants, monkeys, birds and other exotic creatures. In the New World, Montezuma, emperor of the Aztecs, included pumas among his captive wild beasts. And ancient South American artwork often featured jaguars and cougars sitting next to people. Many of these private collections of wild animals ultimately became zoological gardens open to the public. Later, resourceful individuals took caged wildlife on the road as travelling exhibits.

In Canada and the US, hunters and farmers sometimes trapped and displayed bears, cougars and other animals for a small fee. Eventually exotic animals from overseas were imported, thus introducing mobile menageries and circuses to the continent. Many of these enterprises were small; others, such as the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, initially billed as the “World’s Greatest Menagerie,” gained worldwide reputations. North America’s first official zoo opened in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1847.

Although some criticize the concept of zoos, they are the only way many people will ever see some wild and exotic animals in person. And an accredited zoo is a huge improvement over the old shoot and stuff it method of studying wildlife that was predominant in former times. As for animals born in zoos or orphaned in the wild while too young to survive on their own, a zoo can mean the difference between life and death.

Miksa, Keira and Tika were born in a Wisconsin zoo on May 20, 2011, and moved to Cougar Mountain Zoo in Issaquah, Washington, when they were eleven days old. Situated on just over three hectares (eight acres) the zoo is a small, intimate facility housing approximately one hundred animals. The non-profit society is funded by admissions, membership fees and donations. When I visited in March 2012, the nine-month-old cougars still had remnants of their spots. Miksa’s coat was a striking shade of red while his sisters’ coats were a more sombre grey. Their paws and forelegs were already huge in relation to the rest of their bodies and it was easy to see the power in their long rear legs, so clearly built for leaping and bounding. Their small, rounded ears constantly rotated to pick up sounds. As I watched, the trio amused themselves by sunbathing, roughhousing with each other and surreptitiously keeping an eye on the folks watching them.

Miksa, Keira and Tika play king of the mountain at Cougar Mountain Zoo in Issaquah, Washington. Shown here at nine months old, they’ve lived at the zoo since they were eleven days old. Most cougar siblings part ways when around two years old but since these three don’t need to compete for food or other cougars to mate with, they’ll remain close companions throughout their lives. Photo by Robyn Barfoot

At one point, Keira suddenly whipped around to stare intently at the other side of the compound. The focus and concentration was palpable. I moved to see what had caught the cat’s attention and there, at the other end of the enclosure, was a small child. Every time one of the cougars saw a child the cat locked its eyes on the youngster, tracking them until they were out of sight. Children’s small size, erratic movements and high-pitched voices make them look like prey to cougars. I later learned that zoo staff ask youngsters not to run within view of the cougar compound as the movement excites the cats’ chase instinct. And when I asked Robyn Barfoot, the zoo curator, why a cougar was fixated on a volunteer sweeping the walkway, she explained that the person’s downcast eyes and slightly bent position made them appear vulnerable.

Miksa spent most of his time as close to the people side of the enclosure as he could get. Although he didn’t make eye contact, he frequently emitted a soft coughing sound. I thought he had a cold but it turns out chuffing is a way cougars communicate with each other and, in this case, nearby humans, sort of a big kitty way of saying hello. The only other sound the siblings made was a bird-like chirping, the standard “Hi” or “Where are you?” call between siblings, and with their mother (or in this case familiar zoo staff or visitors). Other than that, the cats were totally silent; their oversized padded paws made absolutely no sound even when they were running or playing. Once—from a complete standstill—Tika leapt about 1.5 metres (5 feet) high and the same distance across, clearing a bush and her sister along the way. The entire motion was graceful, agile and eerily soundless.

At the time the two females weighed approximately 29.5 kilograms (65 pounds) each while their brother—males typically weigh thirty percent more than females—tipped the scale at 38.5 kilograms (85 pounds). “That’s 85 cougar pounds,” explained big cat specialist Robyn Barfoot. “That means a lot of muscle. Pound for pound, cougars are the most powerful of the big cats. They can take down an animal ten times their body weight while a lion or tiger only kills prey three to four times their weight.”

Barfoot fell in love with large felines after watching world-renowned animal trainer and circus performer Gunther Gebel-Williams in a Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus act when she was four years old. In 2005, after working at several zoos and completing a stint of tiger conservation in India, Barfoot was employed by Cougar Mountain Zoo; she became general curator the following year.

The life of a cougar in the wild is violent and fraught with danger. Adults of both sexes are preoccupied with finding prey and mating. Females expend a lot of energy raising their young while males fight amongst themselves over mates and territory and are often battle-scarred. Disease and dental problems are common and it’s not unusual for kittens to die from starvation or to be killed and eaten by predators including adult male cougars. And sometimes the cats are hit by vehicles or shot by humans. The average lifespan of a wild cougar is eight to twelve years; well-cared-for captive cougars often live until eighteen or twenty, with one resident of Big Cat Rescue in Tampa, Florida, dying just short of its thirtieth birthday.

Cougars are excellent hunters, but obtaining food is a risky undertaking. The cats are chased off their kills by bears, wolves or more dominant cougars and are sometimes injured or even killed while attempting to take down prey. In March 2012, people travelling along Highway 93 near Radium Hot Springs in southwestern BC witnessed a jumble of rocks and snow cascading down a cliff in Sinclair Canyon. At the centre of the avalanche a cougar rode the back of a bighorn sheep, jaws tightly clamped on its throat. When the duo slid to a stop at the end of a more than ten-metre (thirty-three-foot) drop, the cougar, perhaps disturbed by the traffic, walked away. While the sheep was mortally wounded and had to be put down, the cougar tackled and killed another bighorn sheep the following day.

In contrast, Miksa, Keira and Tika lead a pampered existence. They romp in a large compound with a dirt, sand and grass floor and real trees and rocks. There are logs and a towering boulder mound to climb, a couple of caves to hide in and heated platforms to curl up on. Like house cats, cougars may nap as much as eighteen hours a day. Zoo cougars also get regular vet check-ups. The three cats at Cougar Mountain Zoo don’t get an opportunity to hunt, of course, but Tika, the smallest yet feistiest of the lot, killed and ate a bird that flew into the compound and defended the carcass from her siblings until she was ready to give it up. Zoo cougars are fed a manufactured diet that includes marrow, muscle meat and blood—just what they’d eat in the wild. And since free-roaming cougars don’t eat every day, the three fast once a week. After their permanent teeth came in, they were given bones to gnaw on. They also get occasional treats in the way of venison, salmon and steak donated by zoo members and volunteers.

“It’s been my experience that cougars aren’t big on pork,” noted Barfoot. “And they don’t like tongue. Heart and liver seem to be the main attraction for them, then the kidneys.” These preferences make sense as organ meats are packed with nutrients and the heart and liver are the part of a carcass wild cougars generally consume first.

In nature cougars are constantly on the move searching for prey, finding a mate or defending their territory. Cougar Mountain Zoo employees keep their charges stimulated by giving them a variety of toys, moving their “furniture” around and sometimes hiding their meat. They also add olfactory excitement with spices and perfumes, and when the zoo’s reindeer shed, staff scatter some of the fur in the cougars’ enclosure. Except when mating or rearing young, wild cougars generally spend a lot of time alone. (African lions are the only big cats that live together in a pride.) But because Miksa, Keira and Tika won’t compete for food, mates or territory, they’ll remain close companions throughout their lives.

Some big cats in zoos are trained as much as possible to move to commands so keepers can assess their health. This is a big change from the old days when animals were tranquillized to check every little thing. “Each cougar has its own personality. Nashi hated training but Merlin loved it, you’d walk by him and he’d put a paw up or roll over all on his own,” Barfoot said of the zoo’s two previous cougars, both of which died of old age.

According to Barfoot, cougars are the most difficult big cat to train that she’s encountered in her sixteen-year career. “They’re funny, smart and intelligent but also headstrong and mischievous. Tigers, lions and leopards like routines and patterns. Cougars like to change things up and do stuff differently every time. That’s why you don’t see them in many circus acts. On the other hand, captive cougars are the least aggressive of all the big cats.”

Female cougars give birth to litters of one to three, or occasionally more, any time of year. To blend in with their surroundings, the tiny cubs have dark spots on their coats and dark rings around their tails that fade over time. They open their eyes, which are blue for the first year, at around two weeks. In the wild, they stay with their mother learning how to hunt and survive until they’re about eighteen months to two years old. At zoos, big cats are often removed from their mother soon after birth and hand-raised. “This is really beneficial to animals that will never be in the wild,” explained Barfoot. “It allows them to be comfortable around humans and not to hide or feel upset by their presence. It really decreases their stress level and increases their quality of life.”

Zookeepers had full contact with Miksa, Keira and Tika until they were a year old. Then the cats were too big and powerful for it to be safe. “The bond between the animals and keepers is very strong,” admitted Barfoot. “Some facilities allow full contact with adult big cats but it’s Russian roulette. Sooner or later the animal will simply be itself and follow its instincts. No matter how well cared for it is and how strong a bond there is, a cougar is opportunistic. It’s hard for the humans to let go of the full contact but the cats don’t care. Human life holds more value than an animal’s. If someone goes in the cougar habitat and there is an incident, the cat will be put down. We can’t put them at risk just for our desire to be with them. There’s no such thing as a tame cougar.”

Until the three cougars were a year old, zookeepers entered the compound most afternoons to interact with the animals and give a mini-lecture to the public. I had an opportunity to observe one of these sessions during my visit. As 2:30 drew near I could see the cougars getting excited, and when Sasha Puskar and Logan Hendricks approached the door to the habitat the cats rushed over to greet them. Apparently each cougar had formed a close relationship with a particular employee, and Barfoot said they even recognize and respond to regular zoo visitors.

As Puskar began her talk, Keira kept leaping up and chewing her clothes and sucking her hand. Puskar repeatedly pushed the cougar away explaining to onlookers that the cat wasn’t hurting her, just playing. “Zookeepers can have two types of relationships with the animals in their care,” she said. “They can play a maternal role, which means the cougar respects them, or they can act like a playmate, which leaves them open to injury. The cougars don’t realize you’re not as strong as they are.

In the beginning, staff at Cougar Mountain Zoo had physical contact with Miksa, Keira and Tika, but by the time the trio were nine months old they were getting too big and strong for it to be safe much longer. When they were a year old, all physical contact with humans was cut off. Here, Sasha Puskar chastises Keira for being too rough. Photo by Paula Wild

“So, it’s time for me to be mom,” she added grabbing Keira by the neck, throwing the cougar to the ground and holding her there for a few moments. When she stood up, she pointed her finger at the cougar and scolded it in a firm voice. As Puskar continued her talk, Keira stared up at her balefully just like my dog looks at me after I discipline him.

While this was going on, Miksa and Tika had melted into the background to watch the proceedings, one crouched behind a rock, the other by a small bush. Their bodies were clearly visible but they were so still and they blended in so well that if you weren’t aware they were there, you’d never notice them. Periodically, one would creep out, sneak up behind one of the zookeepers and attempt to jump on their back. That’s why there were always two keepers in the compound: one to talk and one to watch. Hendricks and Puskar calmly deflected the leaping cougars with a swing of the arm, but it was clear that soon the cougars would be too large for this casual action to work. Even though the cubs were playing, their activity was obviously leading up to adult stalk and attack behaviour. Being hand-raised and developing strong bonds with humans had not diminished their predatory instincts at all.

“It’s fun to roll around on the floor with an adorable ten-pound cub but it isn’t so cute or safe when it’s an eighty-pound cat,” said Barfoot. “Most people who get big cats as pets don’t have the knowledge or experience necessary to handle them as they mature.”

Cougars end up being kept by humans in a variety of ways. In the old days, if a bounty hunter, rancher or rural resident killed a nursing female cougar, they sometimes captured the young and sold them to zoos or kept them as pets. That’s how fourteen-year-old Pansy, twelve-year-old Pearl and eleven-year-old Marion Schnarr ended up with four tiny cougar cubs in January 1934. When their dad, August, a trapper and hand-logger, brought the young cats home to Sonora Island, BC, the girls, who had lost their own mother four years earlier, fed the cougars warm canned milk from pop bottles fitted with baby bottle nipples.

Two of the cubs died by the summer but Leo and Girlie thrived. According to a 1938 article in the Nashua Telegraph Parade of Youth, the girls treated the cougars like dogs, teaching them to “jump through the girls’ arms, play tug of war, catch food thrown to them, etc., as good as any circus cat.” “Teaching them tricks was easy,” Pansy is quoted as saying. “We just let them know who’s boss. Anytime we want them to stop doing something we slap them. They quit then.”

Leo and Girlie were affectionate and loved to play with the girls but didn’t like men—even August. They’d hiss at strangers and on occasion knock a visitor down and sit on the person until one of the girls hauled them off or August bopped them on the head with a piece of wood. After Marion caught Leo stalking the family pig, the cougars were kept chained up unless supervised. Over time, increasingly heavy chains were needed as the cats periodically broke free to roam the island and molest neighbours’ livestock. But they always came home, and even though they caused trouble, the girls loved and looked after the cats until they died, at ages three and six.

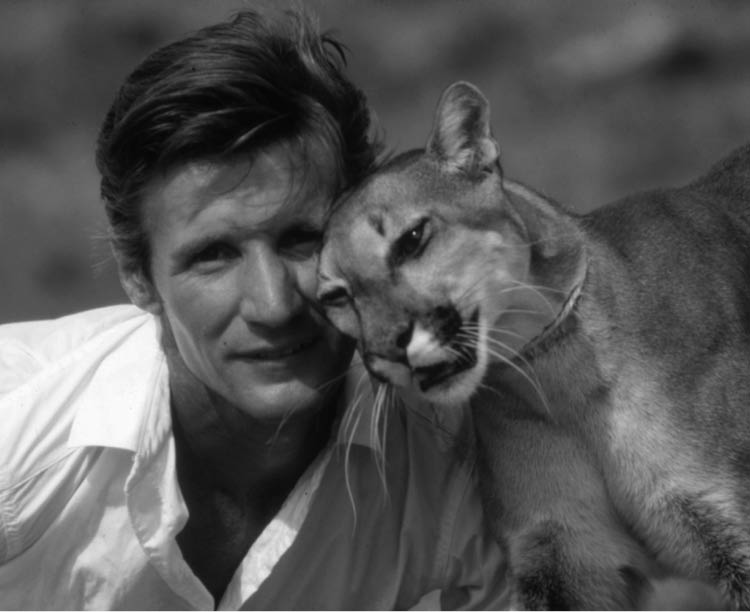

In 1962 Stan Brock, a good Samaritan to orphaned or injured wildlife, was offered a wild puma cub while on a five-minute airline stopover in southern British Guiana (now the Cooperative Republic of Guyana) in South America. He took the cat home with him to the Dadanawa Ranch located in a remote part of British Guiana. There Leemo, as she was called, joined a menagerie that at times included wild cats, dogs, deer, monkeys and other creatures. Brock didn’t tame or train the animals but he named them, fed them, treated their ailments and, in most cases, gave them free run of the ranch house yard.

Born in Britain in 1936, Brock attended private school until his father accepted a job in South America. By age sixteen Brock was working at the large and remote Dadanawa cattle ranch. While there, he became fascinated with wildlife and also appalled at the lack of health care available to people residing in isolated regions. Folks of a certain age may remember Brock as the handsome and daring co-host and associate producer of Mutual of Omaha’s popular television show Wild Kingdom. He went on to star in two movies, write three books and create his own television series, Stan Brock’s Expedition Danger. In 1985 he founded the Tennessee-based Remote Area Medical volunteer corps, a non-profit society that provides free health care services to people in the United States and other countries.

But back in the 1960s, Brock was a bush pilot, a research associate for the Royal Ontario Museum Department of Mammalogy and manager of the Dadanawa Ranch. Leemo soon established her place in the hierarchy of wildlife Brock had taken in. She was buddies with an ocelot called Beano but terrorized all the others. Except Chico, the jaguar. In More About LEEMO, Brock confessed he worried that Chico would break his chain and there would be a terrible fight to the death. Chico was the heavier and more aggressive of the two but Brock described Leemo as having the speed and agility of a “lightweight boxer” and wasn’t sure who would survive the battle.

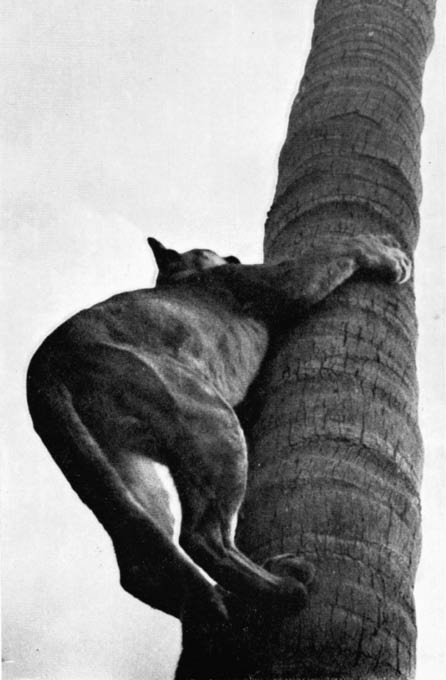

Powerful legs and long claws make climbing trees second nature to cougars. Here a South American puma called Leemo scampers up a coconut palm. Stan Brock, who cared for Leemo, said she could scale a fifteen-metre (fifty- foot) tree faster than most men could run the same distance on the ground. Photo courtesy Stan Brock

Timid around humans when she was young, Leemo became more aggressive as she matured and many of the ranch staff were wary of her. But she was affectionate with Brock and often shared his bed. They wrestled together and she often jumped on his back pretending to bite his throat. “I was never concerned,” he said. “She never even snarled at me.” But Brock was amazed at how easily the puma could knock him down. “She’d run up beside me, wait until one of my feet was at its extreme rear motion and then tap my ankle. It worked every time.” (A Texan with a pet cougar said it used the same technique to trip his children.)

Stan Brock, who later starred in the television series Wild Kingdom and Stan Brock’s Expedition Danger, became involved with wildlife when he managed the Dadanawa cattle ranch in South America. He formed a close bond with Leemo, who often shared his bed. Photo courtesy Stan Brock

Leemo employed this method of bringing down prey when she tackled the ranch’s cattle, sheep or horses. Brock once watched her raise a front paw and run on three legs beside a sheep waiting for the perfect moment to strike its ankle. And on several occasions he saw her stalk a flock of quails then rear up as they took flight and bat one into her mouth with a paw. Leemo always chirped and came when Brock called her unless she was in stalking mode. Then, nothing except a vigorously wielded broom or a slap on the head would get her attention. Brock tried to prevent the cat from killing ranch animals but was never angry when she did, as “she was only acting on her instincts.”

When Leemo stalked an animal, she placed each hind foot in the exact spot the forepaw had been. And even when circling around, she never took her eyes off her prey. Brock often observed Leemo reacting to moving objects more than a kilometre (up to a mile) away and was convinced that her eyesight was “as good at a distance as a human’s and a lot better at short range.”

Brock considered Leemo’s greatest assets her speed for short distances, her coordination and her strength. “She can catch a deer from a standing start with a twenty-yard handicap, hit top speed within thirty feet and maintain that for well over a hundred yards,” he wrote. “Her athletic prowess probably surpasses that of any other feline, regardless of size, including the leopard. She leaps from tree to tree like a monkey grabbing a branch by the forepaws and, as it gives way, leaping to another. It’s like watching Tarzan swing through the trees.”

When Leemo was four she died while Brock was in Venezuela. “She got into a fight with her friend Beano,” he said. “She outweighed him many times over and had him down on the ground and was on top of him. But the ocelot grabbed Leemo by the throat and hung on until she asphyxiated. No one was able to stop them in time.”

In addition to providing a home for orphaned animals, some individuals, like David and Lyn Hancock, have obtained cougars for educational purposes. The Hancocks were planning a film series that would encourage people to respect and conserve wildlife in British Columbia. When a cougar hunter shot a female near Campbell River, BC, and planned to use her four kittens as training bait for his hounds, David intervened and took them home. The couple lived in a small bungalow in Vancouver; Lyn taught at a nearby elementary school while David studied zoology at UBC. Their dream was to buy property on Vancouver Island and open a small zoo to promote conservation.

“Private zoos were much more prevalent in 1967,” Lyn said. “I knew quite a few people who kept cougars but everyone was supposed to have a scientific or educational permit. Attitudes were different in those days and keeping and displaying wildlife wasn’t uncommon. Regulations are much stricter now.”

In her book Love Affair with a Cougar, Lyn related how the cubs joined the Hancocks’ menagerie of dog, fur seal and a variety of local seabirds and raptors. “They were all for research or education or breeding in captivity because populations were dwindling in the wild,” she said. Lyn taught a class of high-IQ students and was able to create her own curriculum, so from time to time the cougars and other animals accompanied her to school. Some also appeared on television programs. Eventually Lyn found foster parents for the three female cougars, keeping only Tom at home. Right from the beginning he was the most docile and people-friendly. Lyn later discovered why. He had cataracts and could hardly see.

All the cubs formed strong attachments with their caregivers and Tom, perhaps because of his disability, was especially close to Lyn. There were a few tense moments: when young, the cougars often escaped over the back fence to roam the neighbourhood and they all showed an unhealthy (from a human’s point of view) interest in small children. And once on a trip to Little Darcy Island to let the cougars roam free, Tom became extremely jealous of a friend of Lyn’s, causing her great concern.

“It’s hard to resist a cute cuddlesome fur ball with blue eyes who begs to be fondled,” Lyn wrote in her book. “It’s almost impossible not to pick it up, let it lick your cheek, jump in your arms, knead and paw. But when that same kitten with its grown-up teeth, sandpaper tongue and towering body pins you to the ground and you yell for him to stop or you turn on the water hose or hit him with a two-by-four, he is going to feel frustrated and never comprehend. You have turned on him, not he on you. He has done the same all his life, so why not now?” Friends who owned cougars told Lyn it was best not to let them jump on or knead humans when they were young as they’d be too rough when they got older. But it was already too late.

After the Hancocks moved to Saanichton on southern Vancouver Island, Tom was boarded at zoos up-island while a suitable enclosure was prepared for him. But Lyn, who’d never had or even liked cats, had fallen in love with the cougar. Every weekend she found a way to visit and spend the day with Tom in his cage. A video a friend made showed Tom’s reaction when Lyn gave a chirping whistle from the parking lot. He’d pace and gaze in the direction she’d approach from, obviously excited.

“People freaked out when they saw me in the cage,” Lyn recalled. “He’d run and jump, knocking me down, then knead my body with his massive paws and suck on my fingers just like any kitten who has been removed from its mum when young. His tongue was like sandpaper, I had to put bandages on my fingers to protect them.” Zoo visitors often thought Lyn was being attacked. She wasn’t frightened, however, as she knew Tom was only playing. But she knew it was a dangerous game. “It was teetering on the edge,” she said. “As Tom matured and grew larger, he played rougher. Sometimes he forgot to sheath his claws or bit when excited. Even though we both weighed about 150 pounds, I didn’t have nearly the strength and agility he did. I was worried a few times.

“People must have a reason to have a cougar, educational, scientific or otherwise,” Lyn emphasized. “Because of their strength and underlying predatory instinct they can be a danger to others. You can’t ever entirely trust a wild animal—as far as they’re concerned, they’re doing the right thing, doing what they’re meant to do.”

Against Lyn’s wishes, David took the cougar with him as he toured northern BC communities with their first feature film, Coast Safari. In Fort St. James a young native boy ran by the cougar as it was being brought into the community hall. Attracted by the movement and the smell of dried moose blood on the boy’s jacket, Tom grabbed the boy’s sleeve and wouldn’t let go. It took David and his assistant a while to get the boy out of the jacket with Tom hanging on the whole time. No one seemed overly disturbed—two RCMP in the audience didn’t even get up and the film proceeded as planned. The boy needed a few stitches but was otherwise unharmed. But worried about the possibility of similar incidents, David had Tom put down that night.

Unfortunately, the life of many captive cougars is not as comfortable as Tom’s younger years or what the trio residing at Cougar Mountain Zoo are experiencing. It’s estimated that a thousand or more cougars are privately owned in the eastern United States. Figures are even sketchier in Canada; some say there are probably two hundred or so in Ontario alone. But those are only guesses, as many big cats are kept illegally.

“Things are different now but in the past you could buy a tiger or lion for five hundred to a thousand dollars, but a cougar only cost a hundred and fifty,” said Carole Baskin, founder and CEO of Big Cat Rescue. The Tampa, Florida, non-profit society is the largest accredited sanctuary in the world dedicated entirely to the care of abused and abandoned big cats. The Captive Wildlife Safety Act was passed in the United States in 2003, making it illegal to sell big cats, including cougars, across state lines as pets. But many people get around that by obtaining a USDA licence, which means the animal is used in some sort of commercial venture. “Unfortunately, it’s still far too easy to buy and sell cougars from one state to another,” said Baskin.

People purchase cougars for a variety of reasons. They might want to breed and sell them or add a big cat to their roadside zoo. Or maybe they spot a cub at an auction and decide to “rescue” it. Some people are interested in big cats and become collectors. Others want the prestige of owning an exotic pet. And there are even stories about drug dealers releasing big cats during police raids to distract officers while they escape out the back door.

Websites blatantly advertising “cougars for sale” are no longer common, but those in the know say the internet is still a good source for prospective buyers. Or sometimes it’s as simple as responding to a carefully worded ad in a newspaper or magazine. “There are lots of people who breed big cats in their backyards or basements,” said Rob Laidlaw, executive director of Zoocheck, a Canadian charity that was established in 1984 to protect wild and captive wildlife. “Breeders often say big cats will only mate if they’re healthy and happy but that’s not true. I’ve encountered cougars kept in a Toronto basement with dead cubs in a freezer.

“In the past, you could just drive up to a place, buy a cougar and drive out,” he added. “There’s more scrutiny and criticism about that sort of thing now so you’d probably have to get to know someone and get them to trust you first. But there are still a tremendous number of people who deal in captive wild animals, often with no questions asked.”

Exotic or alternative animal auctions are another source of big cats. Regulations about owning cougars vary from strict to nonexistent depending on the province or state. Even if legislation is in place, many people get around it by claiming the animal is part of a roadside zoo and is being used for educational purposes. And sometimes they are. But the reality is that many small zoos are not accredited and all too often animals live in deplorable conditions.

Based in Toronto, Zoocheck inspects public and private zoos across the nation and investigates reports of captive wildlife being abused or kept in unsatisfactory conditions internationally. “Captive wildlife in Canada is under provincial jurisdiction so the rules differ from province to province when it comes to keeping, breeding or selling cougars,” explained Laidlaw. “This means there are no standards in some jurisdictions for animal welfare, management or safety. I recently saw facilities with big cats behind two-metre-high fences. The people working there don’t realize that with the right trigger, a mature cat could easily jump the fence and kill someone. Visitors assume they’re safe but that’s not necessarily true.

“Some provinces do a lot, others do nothing,” he added. “For instance, Ontario has no regulations regarding exotic wildlife in zoos, kept as pets or in menageries. A person could go out today and buy a cougar, tiger, spitting cobra and monkey, stick them in cages and put up a zoo sign without any pre-inspection or licensing. In Ontario you need a licence to operate a hot dog stand or nail salon but not a zoo.”

Keeping a captive cougar is way different than having an oversized house cat. Cougars require a large enclosure that resembles their natural habitat as much as possible, along with a prepared zoological diet to ensure proper nutrition. And they need regular check-ups by vets specializing in big cats, as well as enough physical and mental exercise to keep them fit and stimulated. This maintenance requires a huge investment of time, commitment and money. Adequate fencing alone could cost seventy thousand dollars or more.

Authorities estimate that the majority of big cats being kept as pets are illegal. If a person wants to be legitimate, they need to research and pay any licensing fees required in their region and possibly purchase insurance as well. In 2008, one Ontario man was forced to pay a $5,500 annual insurance premium to keep the cougar he’d hand-raised since it was a kitten. Apparently finding an insurance company to cover the cat—Lloyd’s of London finally agreed to do so—was almost more difficult than raising the money. Another drawback with big cats as pets is that they spray urine to mark their territory. Not only is it messy and stinky, but it’s nearly impossible to get rid of the strong ammonia-like smell.

But the biggest problem is that, around age two, the formerly adorable kitten becomes difficult or even impossible to handle. Despite the best of intentions, the reality is that very few people outside of accredited facilities have the resources, knowledge and experience to safely care for a big cat once it matures. A person who purchases a cougar kitten may be able to hold and play with it for up to a year and then have the responsibility and expense of feeding and looking after a pet they can’t touch for the next twenty.

The responsibility of securely maintaining a captive big cat is no small matter. There are numerous accounts throughout Canada and the US of “pet” cougars suddenly and seemingly without provocation reaching through cage bars or scaling four-metre (fourteen-foot) fences to attack people. In 2001, a pet cougar in Nevada escaped and hopped aboard a school bus. Luckily, no children were present and the driver exited unharmed, shutting the door behind him. More than one child has been mauled at a birthday party where a cougar was the featured attraction. And even cougars that have been bottle-fed by their owners since they were tiny have caused trouble. In June 2005, an Ohio resident was loading his 90-kilogram (200-pound) cougar into a van to take it to an educational program for Cub Scouts when it attacked him. The same month and year, a New Jersey man suffered severe injuries from his hand-raised cougar. And being declawed and having filed teeth didn’t prevent a pet cougar from severely mauling two children in Texas.

“At Big Cat Rescue, we’ve found that after leopards, cougars are the scariest big cat to handle,” said Carole Baskin. “If a cougar sees a child or small volunteer, they instantly and constantly focus on them as easy prey. Nothing you do will divert a cougar’s attention once it fixates on someone—you can bang on the cage or spray it with a water hose and it will still remain fixated on what it sees as easy prey.”

Cougars fixate on potential prey—be it wildlife, livestock, a pet or a human—with an incredible focus that is extremely difficult to disrupt. And when it comes to humans, they’re particularly attracted to young children and small adults, perhaps because they appear more vulnerable.

So far, there is no record of any person being killed by a captive cougar. But there have been some close calls. Doug Terranova, an exotic animal owner and circus trainer based out of Dallas, Texas, had worked with big cats for thirty years when he was attacked. Like most in his profession, he’d experienced dangerous moments. But as Terranova explained in the Animal Planet documentary Fatal Attractions: The Deadliest Show on Earth, the decision to clean his cougar’s cage on his own nearly cost him his life.

It was a cold day so he phoned his employees and said he’d look after the animals himself. When he got to the cougar’s cage, Terranova realized he was breaking his rule about no one entering the enclosure on their own. But he’d worked with the cougar for close to fifteen years, so figured it would be okay. Since it was cold, he decided to scatter sawdust on the floor and sweep it up rather than hosing out the cage. Looking down at the floor and bending slightly put him in a vulnerable position. Being alone made him even more so. And when he scooped the sawdust into a large garbage bag, picked it up and turned his back, the cougar’s predatory instincts kicked in. It leapt on Terranova, severely mauling him before he could escape.

It’s extremely difficult to get rid of a pet cougar after it’s outgrown its welcome. Most zoos only accept young orphaned cougars or those that have been born in another zoo. So people sometimes sell their unwanted animals to canned shoots. In these situations an animal is kept in a confined area so it cannot escape and it is then shot. At one time, internet hunting—allowing the “hunter” to shoot the animal with a remote-controlled gun from their computer—was even proposed by some.

Other times, people simply release big cats that are no longer wanted. While it’s possible a cougar raised in captivity could survive in the wild, their chances of making it decrease radically if the animal has been declawed and/or defanged. And familiarity with humans, combined with having no hunting experience, means these cats may approach people or otherwise act inappropriately and be shot. Wildlife agencies believe that many cougar sightings in eastern Canada and the eastern US are of cougars that have escaped or been released from captivity. It’s not unusual for sightings to spike after legislation is introduced that requires owners to spend money on licences, insurance, cage modifications and/or beefed-up security. Some cougars end their days in big cat sanctuaries but many have been closed due to lack of funding or are already operating at capacity.

All too often, once they mature, pet cougars are banished to a pen in the garage or backyard where they become isolated, bored or worse. Unfortunately, the ultimate fate of many captive cougars is one of abuse and neglect. One cougar cub in Texas was bought under the table for fifty dollars. Her claws had been removed with wire cutters and her paws became infected. And when her baby canine teeth were ripped out, her jaw abscessed. Another cougar, in Nevada, was kept in a chicken coop on a .58-metre (23-inch) chain for six years.

But perhaps the most heartbreaking story belongs to Max. He spent a decade confined in a 3.5 by 3.5 metre (12 by 12 foot) horse stall in a barn in Poetry, Texas. Adjacent stalls contained nine more cougars, nine African lions and one tiger. The only outside light came from two windows high on a wall and the animals were never let out of their pens, never received any mental stimulation or veterinary care, and only had minimal interaction with humans. When their owner died the summer of 2011, people attempting to care for the animals didn’t know what to do beyond tossing packages of meat still wrapped in plastic into their pens.

Max spent the first ten years of his life confined to a barn stall with little or no exercise, mental stimulation or veterinary care, and irregular supplies of food and water. When his owner died, volunteers from Big Cat Rescue drove Max to his new home at Safe Haven Rescue Zoo in Imlay, Nevada. There he romps in a large outdoor enclosure and has everything he needs. Lynda Sugasa, executive director of the facility, said, “Despite his horrible past, Max is a very sweet cat and purrs constantly.” Photo courtesy Safe Haven Rescue Zoo

In-Sync Exotics, a Texas-based wildlife rescue and education centre, was called in. When they arrived the big cats were emaciated, dehydrated and sick and their enclosures and water containers looked like they hadn’t been cleaned in years. In an empty stall they discovered a shallow grave filled with the bones of previous feline residents. The non-profit society found a new home for Max at Safe Haven Rescue Zoo in Imlay, Nevada, but had no way of getting him there. That’s when volunteers from Big Cat Rescue agreed to donate their time and expenses for the nearly 8,850-kilometre (5,500-mile) journey. Until he was loaded in the van for the trip to Nevada and released at Safe Haven, Max hadn’t been outside or walked on grass for ten years. Today, staff at the sanctuary say he always bounds out of his den to greet them with a chirp and purrs continuously.

Private ownership of big cats gained international attention in October 2011, when Zanesville, Ohio, resident Terry Thompson released his collection of wild animals shortly before committing suicide. Due to public safety concerns officials were forced to shoot and kill nearly fifty animals, including three cougars. Not long afterward, organizations like Big Cat Rescue, the International Fund for Animal Welfare, the Humane Society of the United States and others were lobbying for the passage of the Big Cat and Public Safety Protection Act, which, if passed, would make it illegal to breed or possess big cats as pets in the US. People already owning cougars would be allowed to keep them providing they met certain regulations, and highly qualified, licensed facilities—such as accredited zoos, wildlife sanctuaries and research institutions—would be exempt.

As of mid-2013, Canada had no federal animal act regarding big cats and other animals in zoos or menageries. “Right now in many areas, municipalities have to deal with any problems,” said Rob Laidlaw. “As well intentioned as they may be, they don’t have the knowledge or expertise required. It’s a ridiculous and inconsistent mishmash of rules and regulations from one province to another. Canada’s a terrible country when it comes to captive wildlife legislation; they have better regulations in China and India.”

Keeping wild animals in captivity is a contentious issue and, in the case of big cats, potentially dangerous to both the animals and humans. The emotional appeal of a small, furry kitten might be hard to resist but the plight of many captive adult big cats is deplorable. US and Canadian governments need to join forces to enact and enforce legislation that will ensure the well-being and secure containment of wildlife in captivity, as well as the safety of any humans they may be near.