His whole movement more silent than the drift of the down that the wind blows from dry fireweed.

—Roderick Haig-Brown, Panther

“You got a cougar in there,” yelled Charles Wuester. It was just after 11:00 p.m. and parking attendant Tim Loewen wasn’t sure he’d heard the Blue Bird taxi driver correctly. But when the man repeated himself, Loewen closed the metal security gate of the underground parking lot just in case. Then he jumped in the cab to tour the three-hundred-car parkade. They didn’t get far before the headlights revealed an animal. It was March 3, 1992, and there was a cougar at the venerable Empress Hotel. And unlike the tiger whose skin was hanging above the fireplace in the Bengal Lounge upstairs, it was very much alive.

When night manager David Woodward answered Loewen’s phone call, he was sure the sighting was a mistake. How could a cougar make its way along busy city streets into downtown Victoria? The Empress Hotel was across the street from the bustling Inner Harbour and kitty-corner to British Columbia’s legislative buildings. Woodward decided Loewen must have seen a big yellow dog. But earlier that day the Times Colonist had run an article warning residents that a cougar had been spotted at the University of Victoria, Uplands Golf Course and Beacon Hill Park, each sighting a little closer to the heart of the city. To be on the safe side, Woodward had bellboys lock the doors connecting the garage to the hotel.

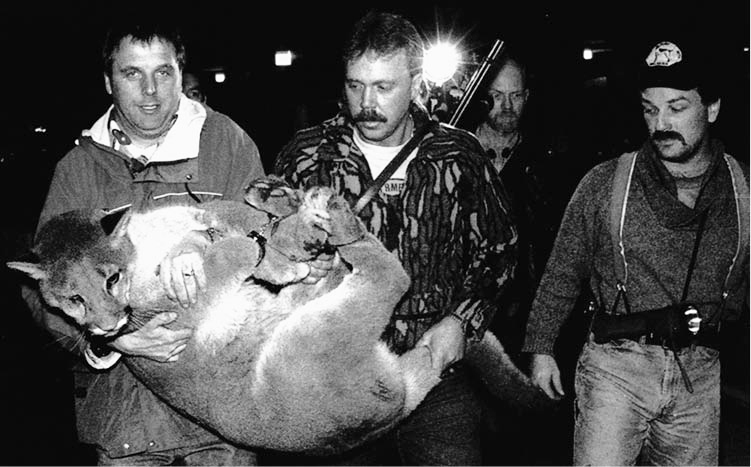

According to Cat Attacks: True Stories and Hard Lessons from Cougar Country, when conservation officer Bob Smirl arrived at the Empress a crowd of two hundred, as well as an assortment of newspaper and television reporters, were gathered outside the hotel. Smirl, two dog handlers, their hounds and a police officer entered the parkade sometime after midnight. They were armed with a tranquillizing gun and a .30-30 Winchester. The cougar, no doubt feeling threatened, went for the dogs. It took three tranquillizing darts to knock it out. After a bit of show and tell outside the hotel, the 60-kilogram (132-pound) cougar was taken to a remote area up-island near Duncan. It was approximately four years old, in good physical condition and hadn’t acted aggressively toward anyone, so the cat was a prime candidate for relocation.

Even people who work in the woods rarely see a cougar. So it’s a shock when one’s encountered in an urban setting. But the big cats visit metropolitan and residential areas more often than most people realize. In Island Gold, author Dell Hall lists twenty-one cougar sightings and incidences between 1902 and 1989, all occurring within eight kilometres (five miles) of Victoria city boundaries. And several, like the 1926 shooting of a cougar behind the Carnegie Library building on Yates Street and the 1961 killing of another in the doorway of Mac & Mac’s hardware store in the 1400 block of Government Street, took place in the downtown core.

Few people see a cougar in the wild, so discovering one at the Fairmont Empress in downtown Victoria, BC, was a huge surprise. Escorting the sedated cat out of the underground parking garage is (from left) Sgt. Gary Green, Victoria Police Department; Frank Wolf, Saanich Fire Department; and Shane Brady, houndsman. Photo courtesy the Fairmont Empress

George Pedneault lives in Sooke, BC, about a thirty-minute drive from Victoria, and has tracked cougars for sixty years. He believes generations of cougars have followed the same trails into Victoria for as long as the big cats have been on the island. “It’s not something we’d recognize as a trail, it’s something triggered in their heads,” he explained. “A cub won’t know to walk along a certain way but somehow it recognizes a path that’s been used by other cougars. They won’t follow it exactly but they won’t be off by more than a hundred feet. And they don’t identify it from scent markings—it can be two or more years since another cougar has passed that way but somehow they know.”

Pedneault suspects many cougars swim across a narrow section of Finlayson Arm and work their way into Saanich and then downtown. “There’s a big rock next to the Uplands Golf Course and if a cougar’s in the area, they seem to always go by that rock, I’ve tracked lots of cats from there.” He says others probably travel through the vast green spaces of the Highlands to Sooke and Mechosin, eventually finding their way to Esquimalt, only a short distance from downtown Victoria.

These cats might be surprised to find themselves in such developed human habitat, but it turns out cougars aren’t all that unusual in urban areas. An August 2011 article in the Issaquah Press revealed details of a study conducted by Brian Kertson as part of his doctoral thesis at Washington State University. Using GPS and radio collars, he documented the travels of more than thirty cougars in the northwestern portion of the state from 2003 to 2008. Among other things, Kertson discovered most of the cats spent seventeen percent of their time in built-up areas. The majority were mature animals who moved through the urban landscape quickly and for brief periods of time. Nonetheless, they were frequently within 500 metres (550 yards) of residential developments, yet rarely noticed.

A telemetry study of eighteen mountain lions near Prescott, Arizona, in 2006 and 2007 revealed that twelve visited urban residential areas. Some did so often while others only made brief forays and left. A number were simply passing through, but some used urban areas as part of their normal habitat. Despite the sometimes frequent proximity of humans, the only time anyone saw or heard about a mountain lion was if one was hit by a car or killed by a hunter. And, at the 10th Mountain Lion Workshop—a forum for research biologists and wildlife managers—held in Bozeman, Montana, in 2011, four presentations focused on cougars living near urban or exurban environments, including Los Angeles.

Dr. Mark Boyce, professor and Alberta Conservation Association Chair in Fisheries and Wildlife at the University of Alberta, where five major cougar studies have taken place from 2004 to 2013, noted, “Cougars adapt fairly well to human presence. They are very secretive. They’ll be right in amongst houses in suburban areas and most of the time no one ever sees them.” Niki Wilson knows this is true. She was a child in the 1970s when a female cougar with bad teeth bedded down under a neighbour’s trailer to have her kittens. The cougar fed on neighbourhood pets and lived in the densely populated Jasper, Alberta, trailer park for weeks before it was discovered.

Unexpected encounters with cougars can happen anywhere, anytime. At the Port of Kalama in Washington state, workers were shocked to see a large cougar at the brightly lit and noisy dock at 1:30 a.m. one night in July 2011. Another middle of the night encounter occurred the same month when RCMP followed a cougar into the town of Sydney, BC, and watched it casually saunter through yards and past businesses on one of the main streets. In December that year, travellers arriving for an early morning B C Ferries sailing had to wait outside the Swartz Bay terminal until a cougar hiding under the administration building was destroyed.

Around noon one day in October 2003 a male cougar was found in the commercial district of Omaha, Nebraska; it wasn’t until someone spotted a long tail sticking out of the bushes surrounding the Lewiston, Idaho, Safeway store parking lot at 3:00 p.m. in May 2011 that anyone realized a cougar was there. Two months later a resident of Bonner’s Ferry, Idaho, looked up from his dining room table to see a cougar staring at him through the sliding glass door. He said it didn’t appear concerned about being in a residential neighbourhood and walked around just like a pet would. A janitor noticed a mountain lion in the courtyard of an office building in downtown Santa Monica, California, at 6:00 a.m. in May 2012. One morning in August 2012 a cougar tried to enter Harrah’s Casino in Reno, Nevada, via the revolving door, and in May 2013 a mountain lion was found hiding in an aqueduct in downtown Santa Cruz, California.

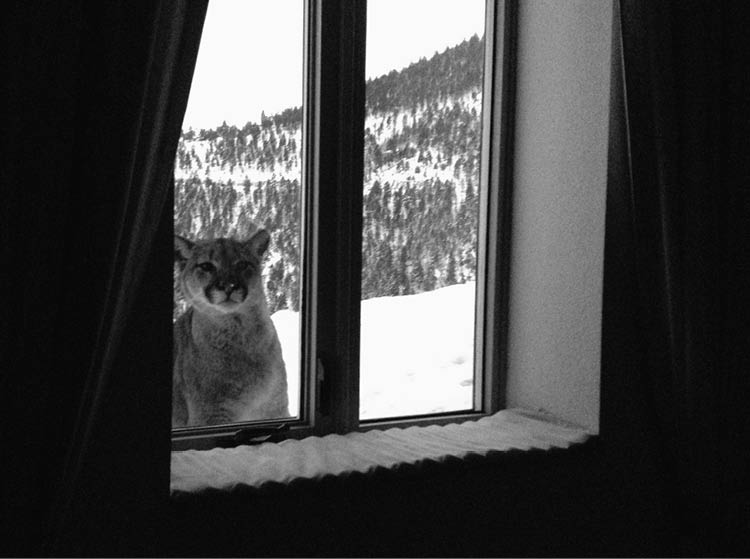

John and Verena Vomastic knew wildlife roamed around their Manitou Springs, Colorado, home during the night but they weren’t prepared to see a mountain lion staring through the window in broad daylight. At one point the cat stood up and put its paws on the window and the Vomastics worried it would break the glass. Luckily, the young adult decided it had seen enough and sauntered away. Photo by Verena Vomastic

For the most part, cougars make their way into urban areas by way of river drainages, golf courses, parks and greenways. They end up in unusual places for a variety of reasons. To begin with, a burgeoning human population means more subdivisions, many of which are located on formerly vacant property and often abut land that’s still in its natural state. No bounty means that in some areas the cougar population is larger than it was fifty years ago. Deep snow can bring cougars into areas where it’s easier to hunt. And if there’s a shortage of their preferred food source, deer, cougars may go into or near communities to hunt raccoons, squirrels and other small animals. A dog or cat can become an easy meal and one a cougar will look for again. Deer are an attractant too, of course. So if Bambi and cohorts are chowing down on the courthouse lawn, it’s entirely possible a cougar will drop by for dinner.

It’s the cats that don’t make their way out of town or find good hiding places before dawn that are apt to get in trouble. Most normal, healthy cougars avoid humans and are adept at observing without being seen. So if one starts showing itself during the day or acting nonchalant around people in an urban or suburban environment, something is wrong. The cougar may be habituated, old, weak, sick, young or overly curious. The Cougar Network’s 2007 Puma Field Guide noted that “puma seemingly have become less wary of humans near residential or recreation areas in puma habitat.” If a cougar’s not afraid of humans, people need to be extremely cautious around it.

Most adult pumas have a permanent home territory, which can encompass 390 square kilometres (150 square miles) or more. A female with kittens, however, will significantly reduce her range to remain close to her young, yet has the added pressure of finding more prey to feed her family. Photo courtesy Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Many cougars that appear in inappropriate places are young juveniles. When cougar cubs separate from their mother, usually at around eighteen months to two years of age, they need to become self-sufficient. Like riding a bike, taking down a deer or even a raccoon takes some practice before any real skill is developed. And finding and killing prey is even more difficult for cubs that have been orphaned or abandoned at an earlier age, so some young cougars may come to town looking for a meal that’s less strenuous to obtain.

The biggest challenge for young adult cougars is the struggle to find their own territory. Most mature cougars have a permanent home range that may fluctuate with the seasons. Range sizes vary depending on prey density, terrain, habitat and whether a female has kittens or not. According to Cougar Ecology and Conservation, edited by Maurice Hornocker and Sharon Negri, males typically have larger ranges than females, which in good conditions can be roughly 195 to 390 square kilometres (75 to 150 square miles) and 65 to 130 square kilometres (25 to 50 square miles) respectively. If prey is scarce or habitat is poor, a male’s range may be as large as 1,800 square kilometres (700 square miles) or more. Although male territories may overlap to some degree, in most cases they go to great lengths to avoid each other.

According to Cougar Management Guidelines, a collaborative effort by thirteen cougar biologists and wildlife managers to synthesize all information about managing cougars available up to 2005, virtually all young adult males disperse about 85 to 100 kilometres (53 to 62 miles), or sometimes further, from their birth area, which may be a way of ensuring genetic diversity. Females, however, are more social. It’s estimated that fifty to eighty percent of female offspring either replace a resident female in their home range or establish a territory that partially or fully overlaps with other breeding females. Young males have the most difficulty finding a spot to claim as their own. If they venture into a mature male cougar’s territory they will be chased out—or even killed.

While mature mountain lions may visit or pass through urban areas, it’s often young adults that get into trouble. They’re still fine-tuning their hunting skills, as well as trying to establish a territory of their own. This is a risky time for the young cats, especially males who are often challenged or even killed by mature males defending their territory. iStockphoto

Like human teenagers, young adult cougars may be full size, or nearly so, but haven’t quite figured out how to make their way in the world. And they don’t always display the best judgement when it comes to honing their survival skills. These are the cougars that often find themselves in tough situations. And it isn’t always in backyards or city streets. In February of 2011 David Roberts and his wife, Nancy, were enjoying a quiet evening at their Palomar Mountain home northeast of San Diego, California. Then the glass patio door “violently sprung open.” When David saw a mountain lion half a metre (two feet) away from him, he jumped up on the couch and started yelling as loud as he could. Nancy, sitting nearby, added her screams to the racket. Looking surprised at the commotion, the cougar ran out the door. The Roberts think it may have been after their cat, which was in the room with them.

Three months later, Jesse Taylor entered his garage to chase away what he thought was a raccoon or other small animal. The Taylor family lived in Herperia just north of San Bernadino, California. But instead of a raccoon, Taylor found himself face to face with a mountain lion. Fish and Wildlife officials tranquilized the animal and released him in the San Bernadino National Forest. The Taylors suspect the lion had been in their garage for three days.

One night in October 2012, a Dexter, Oregon, couple woke up to find a cougar in their bedroom. Apparently it had chased their dog in through the pet door and upstairs into their bedroom. They ran out on the deck and yelled for help but before anyone arrived the cat had gone back out the door.

“In California it’s nearly an everyday occurrence to have a mountain lion in a garage or in a residential area,” said Marc Kenyon, the black bear, mountain lion and wild pig programs coordinator for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “We’re noticing that mountain lions occur in and around humans and human development a lot more than previously thought. Studies have tracked them with GPS collars that give a specific location every two hours. The results show them moving in and around human habitat and subdivisions and sleeping in backyards on a routine basis yet causing little concern for public safety. For the most part, this is just the reality of how lions make their living in these areas.

“The take home message here,” he added, “ is that we’ve had collared lions in the area for twelve years and during that time only had one type yellow incident, all the rest were green.” The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has a colour-coded system of guidelines that regulates how personnel respond to mountain lion sightings. Green indicates the animal is not acting in an unusual or aggressive manner and there is no cause for concern. Yellow means there is the potential for threat; for instance, a mountain lion is seen near a school when children are getting out. And red signifies a physical altercation between a human and a mountain lion. In 2013 a new policy was adopted that gives officials more options for dealing with potential human conflict situations where the mountain lion has not acted in an aggressive manner.

Cougars may enter buildings out of curiosity or because they’re looking for a place to hide or find prey. And it doesn’t only happen in California. Twenty-four-year-old Denise Mueller was in her bedroom one morning in 1989 when the window of her basement suite in Victoria, BC—approximately 1.5 kilometres (almost one mile) from the Empress Hotel—shattered. A cougar fell through the glass, landing at her feet. Mueller ran into the closet and closed the door. Baying hounds and men barged through the window after the three-year-old cougar, which was shot beside Mueller’s bed.

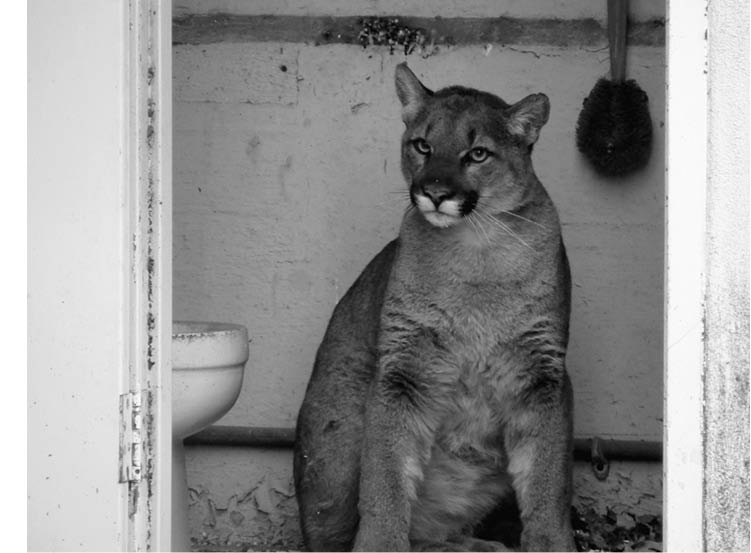

Mountain lions frequent urban areas much more frequently than most people imagine. And they enter buildings on occasion. This young adult was photographed in a restroom at the Chatsworth Reservoir in Los Angeles County. Photo courtesy National Park Service of California

Nine years later, in 1998, Craig Grebicki, a salesman for Scott Plastics, was just about to take a break from making phone calls when he noticed a movement in his peripheral vision. To his amazement he saw a cougar placing its front paws on an interior windowsill. With only a filing cabinet and a potted plant between them, Grebicki held his breath. The cat didn’t seem to notice him and dropped back to the floor and went into another office. But when it passed another interior window they made eye contact. Grebicki shoved his desk chair into the doorway and dashed for the back door. As it closed behind him he heard something heavy hit the other side. At the time, the Scott Plastics office overlooked downtown Victoria’s Inner Harbour and was within sight of the Empress Hotel.

One evening in August 2012, Angie Prime was sitting in the living room of her home in Trail, located in the West Kootenay region of BC. Her two pomeranian-chihuahua puppies were curled up on the couch next to her and her eleven-year-old border collie was asleep on a nearby chair. The small, slight woman was thinking about taking the dogs outside when she saw movement out of the corner of her eye. The next thing she knew a cougar was leaping toward her. Prime screamed as she threw her arms and legs up in an effort to defend herself. Roused from her nap, Vicious, the border collie, jumped out of the chair and chased the cougar outside. Prime escaped with a couple of scratches; an old, emaciated cougar was shot nearby the next day.

In May 2013, Angie Prime and her eleven-year-old border collie/lab cross travelled to Toronto where Vicious was inducted into the Purina Animal Hall of Fame. The previous summer Vicious had leapt to the rescue when a cougar entered an open sliding glass door and attacked Prime while she sat on her living room couch. Photo courtesy Purina Animal Hall of Fame

What has to be the most harrowing account of a cougar entering a building, however, was of an encounter in Kelsey Bay on northern Vancouver Island. Ed McLean, a sixty-two-year-old telephone and telegraph lineman, returned with his dog to the cabin where he was staying late in the afternoon of January 26, 1951. While McLean was splitting wood for the stove he noticed a cougar nearby. He’d seen the cat before and wasn’t concerned but made sure his spaniel came inside with him. Around 9:00 p.m. McLean looked out the window and saw the cat standing not far away, watching him intently. Thinking it might be attracted to the light or movement, he turned the gas lantern off.

As soon as the cabin was dark, the cougar burst through the window, locked its jaws on McLean’s elbow and knocked him to the floor. McLean managed to get on top of the animal and push it toward the table. He didn’t have his rifle with him but there was a large knife on the table. By the time McLean reached his destination, his right arm was badly mauled and his strength was ebbing. Using his left hand, he stuck the knife into the cat’s throat far enough to sever the jugular vein. When the cat stopped struggling, McLean crawled toward the door, calling his dog from its hiding place under the bed.

But just as they crossed the doorsill, McLean heard the cougar coming after them. He quickly closed the door and, for a few moments, listened to the heavy breathing on the other side. Barefoot and dressed only in his long underwear, McLean stumbled to the rowboat. To survive, he knew he had to reach another cabin almost ten kilometres (six miles) across the bay. A strong wind, loss of blood and drifting in and out of consciousness resulted in the voyage taking two hours. At the cabin McLean tried to call for help but was unable to reach anyone. And he was so cold he couldn’t even light a match to start the wood stove. Somehow he managed to cover himself with a sleeping bag before passing out.

The next morning, twelve hours after his ordeal began, McLean made contact with the outside world. When help finally arrived, his blood-soaked underwear had to be cut away from his body. After receiving first aid at the company’s office McLean was taken to the hospital in Campbell River, where he was treated for loss of blood, exposure and multiple injuries. In the meantime, Fred Dingwall and Bill French visited the scene of the attack. As they opened the cabin door they saw the cat’s bloody body lying on McLean’s bed. It was still alive and tried to attack them but they shot it from the doorway. The badly emaciated one-and-a-half-year-old female cougar only weighed 25 kilograms (56 pounds).

Encountering a cougar in a building is extremely rare. But that’s not the only unlikely place they’ve been seen. Due to most cats’ aversion to water, many people assume cougars will avoid the wet stuff unless getting a drink or crossing a shallow stream. But it turns out the big cats are exceptionally strong swimmers and don’t seem to mind the water at all. In Island Gold, Del Hall described a cougar swimming from Vancouver’s North Shore to Stanley Park, more than half a kilometre (a third of a mile) away. He also wrote about two separate cougars that travelled between the Gulf Islands in 1928. Starting at Gabriola Island near Nanaimo, each cat swam to Valdes, Galiano, Samuel and then Saturna, killing sheep at every stop.

The most gripping story Hall told, though, took place in 1930 just north of Tofino on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Jacob Arnet was heading back to the Mosquito Harbour mill where he was caretaker when he thought he saw a dog swimming. He turned the motorboat toward it and, as he got close, realized it was a cougar. He quickly reversed direction but the cat was close enough to grab the side of his cedar clinker-built boat. As it began to climb aboard, Arnet pried a boat seat loose and swung it at the animal, knocking it back in the water. The rudder got hit in the process, resulting in the boat going in circles with the cougar trying to climb into the boat and Arnet doing his best to keep it out. When Arnet finally got the rudder under control, he glanced over his shoulder to see the cougar climbing aboard again. And so the battle continued. Arnet eventually escaped but the sides of his boat were badly scratched.

In 2012 alone, several groups of people out on the water witnessed cougars swimming long distances. Two of the cougars were near Sechelt on the Sunshine Coast of BC while a third was a short ways from Tahsis on the west coast of Vancouver Island. In each instance, the cougar turned and swam directly toward the boat.

While there are numerous stories about how far cougars can swim, one is supported by scientific evidence. In Cat Attacks: True Stories and Hard Lessons from Cougar Country, authors Jo Deurbrouck and Dean Miller mentioned a UBC wildlife program student who radio tracked a cougar from “the wild heart of the island [Vancouver Island] straight through Nanaimo . . . When it reached the busy waterfront, the cougar jumped in and swam four miles through the ferry lane to built up Gabriola Island.”

Cougars usually make their their way into urban areas via green spaces such as golf courses and parks and by following river drainages. They don’t mind water and have been known to swim long distances.

So what does it mean to have cougars sauntering through neighbourhoods, strolling city streets, leaping through windows and attempting to board boats? It’s a reminder that cougars are curious, stealthy, unpredictable and sometimes bold. And that in some regions of Canada and the US, human and cougar territories are overlapping to a greater extent than ever before. More people are living and recreating in cougar habitat and more cougars are visiting and even living and hunting in or near urban areas. Whenever large predators share the landscape with humans the potential for trouble is present. And that means people who live, work or visit cougar country need to know how to respond in the unlikely event they encounter a cougar.