For sheer killing ability, I don’t think any cat

in the world surpasses the mountain lion.

—Maurice Hornocker, wildlife biologist,

British Columbia Magazine

In his autobiography, frontiersman and folk hero Daniel Boone recalled seeing a panther “seated upon the back of a large buffalo” with its claws “fastened into the flesh of the animal wherever he could reach it until the blood ran down on all sides. The bison struggled mightily but to no avail.” Chances are the bison outweighed the panther by at least 635 kilograms (1,400 pounds) but that didn’t prevent the cat from successfully bringing it down.

The cougar is an exquisitely built killing machine. Disproportionally long rear legs provide power for spectacular leaps while overdeveloped front legs ending in huge paws possess superb strength for gripping and slashing prey. Like all cats, cougars are incredibly flexible. As the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission explained, “A cat’s vertebrae are largely held together by muscles instead of ligaments, allowing it to twist, compress, lengthen and turn in pursuit of prey.” An added bonus is that the front legs attach directly to the shoulder blades, letting cats creep up on prey while remaining low to the ground, and loose, baggy skin permits a wide range of motion. Kilo for kilo, a cougar is ninety percent pure muscle. Cougars, especially pregnant females or those feeding young, require a high-protein diet to fuel their muscular bodies. While ungulates graze most of their waking hours, cougars that take down big prey usually follow a feast and fast regime. A cougar that hasn’t eaten in a while may gorge on up to five kilograms (ten pounds) or more of meat and blood at one time. When full, the cat drags or carries its catch a short distance away, scrapes out a shallow recess to stash the carcass in and lightly buries it with sticks and leaves to hide it from scavengers. If natural debris isn’t available, a cougar will make do; once a deer carcass was discovered in a backyard covered by pieces of lumber. After eating, a cougar will usually take a nap in a secluded spot nearby, then feast again, with the whole process repeating itself over the course of one to several days.

Deer are generally the mainstay of a cougar’s diet but they’ll eat any form of meat. This includes large game such as elk, moose and bighorn sheep, as well as smaller animals like rabbits, porcupines and mice. Maurice Hornocker once saw a cougar eating grasshoppers. When researchers in Pacific Rim National Park Reserve on the west coast of Vancouver Island analyzed cougar scat and prey carcasses, they found deer and harbour seals tied in second place as dietary sources, followed by river otters, sea lions and mink. The mainstay of the local cougars’ diet—up to twenty-eight percent—was raccoons.

In a February 2012 Postmedia News article by Larry Pynn, Danielle Thompson, a resource management and public safety specialist in the Long Beach unit of the park, speculated, “Young cougars lacking the skills to take down deer may be exploiting easier, smaller prey. Some cougars may also defer deer hunting to the coast’s dominant wolf packs.” She also pointed out that feeding on marine animals didn’t mean cougars were plunging into the ocean to tow sea lions to land; they were most likely picking off young, old, sick or injured animals resting on the beach.

Most cougars primarily feed on deer but other mammals such as raccoons, beavers and badgers (pictured here) can also form a substantial part of their diet. And, although they are stalkers, cougars are also opportunistic and will evaluate any potential prey that crosses their path.

Just like people, cougars also have food preferences. Although the big cats rarely attack cattle, they have a history of doing so in Arizona. And while researching cougars on Vancouver Island, Penny Dewar noticed beavers were a significant food resource for those living near a swampy area. There are also stories about mountain lions in California with a taste for pork and one in Arizona that was particularly fond of porcupine.

A University of Alberta study in the west central portion of the province clearly showed that individual cats had strong preferences for specific prey. And it wasn’t always a case of game being abundant or convenient to kill; some cougars actually went out of their way to hunt a particular species. “We found some extreme cases of selectivity,” said Professor Mark Boyce. “Big males seemed to really specialize when it came to larger prey. One killed seventeen feral horses, five moose, three elk and two deer. Some would pick off a bighorn sheep and then go get another one; we even had a female cougar that hunted bighorn sheep. They also attacked llamas—people sometimes keep them to guard livestock against predators but that doesn’t work with cougars—we tracked one that killed and ate seven llamas.”

Cougars that take down large prey generally kill a deer every eight to fourteen days. They may roam 20 kilometres (12.5 miles) or so a day in search of food and often shift their range with the seasons depending on where the deer are. Females with young cubs won’t travel as far, and those providing meat for larger offspring need to hunt more often. But no matter what the age or condition, a cougar’s primary goal is to find food.

Due to a relatively small lung capacity, which makes running long distances impossible, cougars are stealth hunters who sneak up on their prey. On beaches, wolves can be seen out in the open, noses in the air or on the ground searching for scent. But a cougar will move through the tall grasses and brush bordering the edge of the sand, slinking behind driftwood and boulders or anything else that provides cover. Harley Shaw, a retired wildlife research biologist who worked for the Arizona Fish and Game Department, noted that the lions he studied seemed to have two basic movements: hunting and travelling. And that aside from closing in on prey or being chased themselves, they seldom moved faster than a walk.

Cougars don’t perch in trees or hide at the side of a trail waiting for their next meal to walk by. But if something happens along, chances are they’ll check it out. They hunt by stalking and are perfectly content to trail prey for an hour or more, waiting for the perfect opportunity to strike. “It’s very unusual for a cougar to stay in one place very long,” explained Boyce. “If we had a radio-collared cougar in one spot for three or four hours, it was always on a kill. We got data from the collars every fifteen minutes. There was always a slow, steady stalk followed by a fast dash at the end, never an ambush.”

“A stalking cougar shows no sign of excitement, it is cool, calm and deliberate,” wrote Roderick Haig-Brown in Panther. “Its instinct is always to follow something, a deer, a racoon, a man . . . it follows not a scent but a motion.” And, like a meditating Zen master, a stalking cougar is intensely focused to the exclusion of everything else. They rarely shift their gaze from their intended victim, even when changing direction or creeping around to another position. In Out Among the Wolves: Contemporary Writings on the Wolf, Barry Lopez refers to the visual exchange of signals between predator and prey as “the conversation of death.”

Just the thought of being stalked by a big cat stirs a primal fear. Actually experiencing the hard stare is an event that becomes indelibly imprinted on the psyche. “It was a beautiful October afternoon after we’d had a lot of rain,” Liz Buckham recalled the spring of 2012. “l wasn’t going to walk far, just to the bridge and back.” But when the sixty-six-year-old reached her destination, the fine day and mellow jazz playing on her iPod persuaded her to keep going. As Buckham passed the last house on the road and headed up a trail, she realized she’d forgotten her knife and small canister of pepper spray. She’d been carrying them on a regular basis as cougars had been reported in the area. But she’d been concerned about cougars for thirty-eight years and had never seen one. In fact, one of the first things she did when moving to Merville, a rural area on the central east coast of Vancouver Island, in 1974 was buy a knife in case she met a cougar. “That was unusual then,” she said. “Everyone thought I was overreacting because I was from Ontario and we didn’t have cougars back east.”

Partway down the trail, Buckham noticed it had grown up a lot since she’d been there last. “Suddenly I felt anxious and picked up two stout sticks, one for each hand,” she said. She could hear someone hammering in the distance and picked up her pace. That’s when she noticed the cougar tracks in a partially dried mud puddle. But they were going the same direction as she was so she hoped the cat was well ahead of her. Then the trail ended and she was back on a road with vehicles passing by. Gradually she relaxed enough to throw one stick away. When Buckham decided to head home, she considered going the long way around on the road but was tired, so she opted for the river trail shortcut.

It was around 4:30 p.m. when Buckham strode up the trail embankment to the road, tossing the other stick aside as she did so. “I’m at the bridge—I’m safe—only ten minutes to home!” she thought. But just as she was about to step onto the wood planking, a flickering motion caught her eye. She thought it was a dog but as it came around the corner of the bridge railing she saw it was a cougar. “I felt its very focused stare. I couldn’t see its eyes because of the lighting but I felt that attention. That extremely focused attention.”

Buckham stopped and so did the cougar. Bending over to get a stick or rock seemed too risky so the petite woman shot her arms straight up in the air as high as she could. “There was no discernible reaction and I felt really vulnerable with my torso exposed,” she said. “A tingling went up my spine and I thought I was going to faint.”

Buckham knew that, no matter what, she couldn’t take her eyes off the cougar. “Go on, get out of here,” she said, not loudly but firmly the way she’d speak to a dog. The cougar kept its head down, staring intently. With her arms still in the air, Buckham wiggled her fingers, hoping the cougar would think she looked too weird to eat. The cat’s ears twitched and she took that as a good sign. She yelled again but the cat didn’t respond so she stamped her foot vigorously.

The stare down continued, then the cougar looked briefly to the side. Buckham hoped it was scouting out an escape route. “Then it moved a paw in my direction,” she said with a quiver in her voice. “The paw tapped the bridge deck a couple of times before he put it down. He was coming for me! I mustered all my energy and yelled as loud as I could, ‘get out of here!’

“I could see its underbelly flopping as it made two leaps and disappeared across the road up a driveway,” Buckham said. “That’s when I realized how big it was. It never made a sound; it was totally silent even when bounding away.”

Buckham didn’t dare cross the bridge to go home so she ran the other way until she found someone to give her a ride. At the bridge they saw a woman and a small child out for a stroll so the driver gave them a lift too. As soon as Buckham got home she called the neighbour to tell them a cougar had run down their driveway. They went out to investigate and saw the big cat darting away from the chicken coop.

Liz Buckham had just tossed the branch she was holding aside when a cougar appeared on the other side of the bridge and began to approach her. Photo by Paula Wild

It’s impossible to know if the cougar had been stalking Buckham but by not hiding or running away, it was most likely exhibiting predatory behaviour. And considering the proximity and the cat’s ability to leap thirteen metres (forty-five feet) in one bound, she was in grave danger. Even though Buckham was not physically injured, for over a year she was afraid to go for a walk or bike ride by herself. Time has dulled the intense fear but she still feels uneasy when she’s at the bridge or bent over in her garden.

Since cougars are sprinters, not marathon runners, they steal up on their quarry, say to within six to fifteen metres (twenty to fifty feet) or so, and then make a short, fast dash—at up to seventy-two kilometres (forty-five miles) per hour—to leap onto their victim’s back. If possible, they like to attack from a higher elevation; sometimes the impact alone is enough to incapacitate the victim or break its neck. Cougars kill by biting the back of the neck to sever the spine, biting the throat to crush the trachea and suffocate their prey, or by reaching forward with a front paw to grab the animal’s nose and pull the head sideways or backward until the neck breaks. Jerry MacDermott, a wildlife technician with British Columbia’s Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, once tracked a cougar in the snow that had ridden an elk’s back down a steep incline for about 90 to 140 metres (100 to 150 yards) until it eventually broke its neck.

A December 2001 video taken in New Mexico and posted on the Cougar Network’s website shows an approximately 70-kilogram (150-pound) cougar tackling a 120-kilogram (265-pound) mule deer. When the video started the cougar was hanging by its front paws onto the side of the running buck and slowly pulling itself on top of the trophy animal. Once astride the deer, the cougar bit the buck’s neck in an attempt to break it. But as the narrator pointed out, the buck was in rut and hormonal changes had caused its neck to thicken. As the buck stopped running, the cougar flopped to the ground, hanging from the deer’s lower neck trying to suffocate it.

The deer kicked the cougar’s head and body repeatedly with its sharp hooves but the cougar never flinched. Using its powerful forelegs and claws, the cougar pulled the deer’s head, then its entire body, to the ground. The buck thrashed and kicked mightily but the cougar held on. Eventually, seeming to realize it needed to change tactics, the cougar released its hold on the neck and clamped onto the deer’s snout, crushing it with its powerful jaws. There is no doubt the cougar suffered serious injuries during the struggle, but from the initial leap to the final scene it only took five minutes for it to asphyxiate its prey.

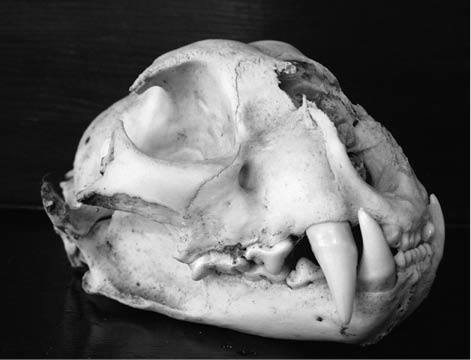

Wild canines primarily rely on scent to find and track their prey, so they have long muzzles and small eyes. Cougars depend on sight more than smell and have large eye sockets. In The American Lion author Kevin Hansen discussed the special membrane behind a cougar’s retina, which reflects light and provides extraordinary vision day and night. It’s estimated a cougar can see in the dark six times better than a human.

Cougars have large eye sockets as they rely on sight more than smell. Their short, muscular jaws are built to open wide and their incredibly strong canine teeth can exert tremendous force. Based on the small size and the teeth, which are small and not worn or yellowed, this skull probably belonged to a juvenile cougar eighteen months to two years old. Photo by Paula Wild

Cougars have relatively small heads with short, powerful jaws built to open wide and long canine teeth—up to five centimetres (two inches) on adults—made for tightly grasping and killing large prey. These very strong canine teeth have punctured and crushed the skulls of wolves, horses and humans and are resistant to bending even under extreme force. The smaller front teeth are used to pluck hair and fur from an animal before it’s eaten, while the blade-like teeth in the rear are for ripping meat from a carcass and cutting through tendons and sinew.

A cougar has four claws on its rear paws and five, counting the dew claw, on the front. These incredibly sharp tools are used to catch and hold prey. Unlike those of bears or canines, cougars’ claws are normally retracted except when they are scratching trees or during an attack. In one news article, Brian Keating of the Calgary Zoo and the University of Calgary referred to a cougar’s claws as “razor blade steak knives.”

Once its prey is dead, a cougar slices open the skin and removes and buries the stomach and intestines. The cat then enters the body from below the ribs and feeds first on the high protein, vitamin-rich liver, heart and lungs. There is no chewing involved, the cat simply rips the meat into strips and swallows chunks whole. Unless it is chased off a kill by other predators or hunters, a cougar normally consumes up to seventy-five percent of a carcass by weight.

Cougars aren’t lazy but they are prudent about their energy expenditure. They’re always looking for an easy meal, even if they’ve recently eaten. Female ungulates that are pregnant or have just given birth are vulnerable, as are newborn fawns. Bucks in heat, with their one-track minds, also fall into this category. Animals that are young, old, sick or injured are at increased risk, especially if they are separated from the herd, or look like they easily can be. This method of selecting prey also applies to livestock and pets, and humans if they hike alone, lag behind or bend over to tie a shoe.

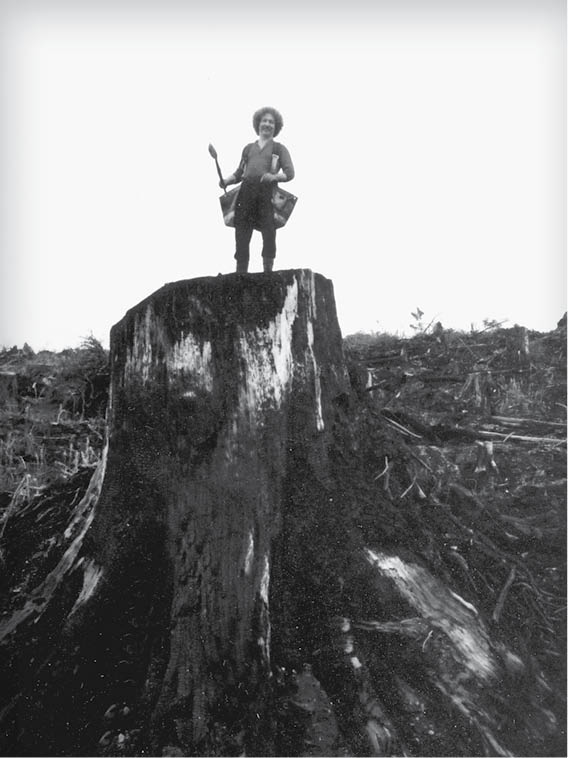

It was a typical misty morning at the Marble River estuary located north of the town of Port Alice on northern Vancouver Island. At the top of the slope a couple of ravens cawed from a stand of old-growth Douglas fir. Jack Scott had planted trees up the logged off clear-cut and was now working his way down the hill. It was February 1991 and he was moving quickly, both to keep warm and to make money as a piece-worker. Around 8:30 a.m. he paused to watch the noisy birds. “They were flying in circles, one would land on a lower branch and then the other would do it. They repeated this over and over,” he said. “I’m really interested in birds and thought maybe this was some kind of courtship ritual. So I kept looking back at them every few minutes.”

When one of the ravens flew straight at the thirty-nine-year-old, he ducked quickly to avoid being hit. “The raven went back to the tree line squawking really loudly,” Scott said. “I couldn’t figure out what they were up to.” He continued planting, working alongside a downed cedar snag that was too big to climb over. Then the hair on his head bristled. Scott planted the tree he was holding and looked over his shoulder but didn’t see anything. As he planted another tree he had a strong feeling he was being watched so he straightened up and turned around.

“The only reason I noticed it,” he said, “is because it blinked. It was a big cougar—maybe 130 to 140 pounds—crouched about 60 to 75 feet away, staring at me intently. In a fraction of a second it was bounding towards me. My first instinct was to throw my shovel at it but I knew if I didn’t brace myself for the impact, I’d be a goner. So I ran forward and hit the cougar in the chest with the point of the shovel.”

Treeplanting shovels have narrow, elongated blades that make them easy to use in the bush. Scott figures the spear-like weapon was the only thing that prevented the big cat from becoming airborne. He shouted but none of the nearby crew heard him. “I startled the cougar when I hit it,” Scott explained, “but it never let up. I began working my way towards the landing, yelling and throwing sticks and rocks at its face and hitting it with the shovel. But every time I turned, it tried to get on my back.”

Scott had changed tree bags that morning and accidently left his emergency whistle in his pack down on the logging road. That’s where he was headed but it wasn’t easy with eighteen kilograms (forty pounds) of trees on his back. The ground was pockmarked with big holes full of rainwater. He fell into several, bruising his legs and soaking his tree bag, making it even heavier. Finally he was able to shrug the bag off. “Then the cat moved in closer and ran beside me,” he said. “I managed to get my Stanfield’s off and threw it quite a ways in front of the cougar. Having something with my scent on it seemed to confuse it.”

With the cougar distracted by his shirt, Scott ran. Reaching his pack, he grabbed his whistle and blew on it continuously as loud and hard as he could. “The cougar came right down to the road and lay down just like a regular cat,” he said. “Its ears were back flat against its head and it was whapping its great big tail—it looked four or five inches thick at the base—on the ground. Then someone else showed up and it went into the bush.

“The cougar never made a sound the whole time it was after me,” Scott added. “If I would have thrown my shovel at it I wouldn’t be here now. As for the ravens, I think they were alerting the cougar to my presence so they’d have something to scavenge.” Ravens do scavenge cougar kills and in The Tiger, author John Vaillant mentioned carrion crows that followed tigers on a regular basis.

When Jack Scott was attacked by a cougar he used his treeplanting shovel to deflect the cat’s initial lunge. He’s shown here at the cut block near the Marble River estuary on Vancouver Island where the attack occurred, holding the shovel that saved his life. Photo by Jean-François Hautcoeur

Twenty-one years later, Scott continues to work in the bush but he is a lot more cautious. “I still go out by myself but I always take a knife and whistle,” he said. “I was arrogant when I was young but you know that saying, ‘Once you step off the road in a remote area, you become part of the food chain’? It’s true, the rules are different out there and most people aren’t fully aware of that.”

Cougars rarely attack humans, but why wouldn’t they? They are carnivores, and people are meat—and with no built in defence mechanisms such as sharp teeth, horns or hooves, pretty defenceless prey at that. Yet the risk of being attacked by a cougar is low to extremely low. Of course, if you live, work or recreate in cougar country, the odds of encountering the big cat and being attacked increase. In the last two hundred years in Canada and the US, cougars have attacked 281 humans resulting in 55 fatalities. That works out to an average of .28 people killed by cougars per year. (Actual figures are probably higher as few records were kept in the early days and some suspected deaths could not be confirmed as caused by cougars.) By comparison, 34,767 people were killed in motor vehicle accidents in the United States in 2012. That’s an average of 95 per day.

Cougars often watch and study their prey as they assess the risk-benefit ratio of launching an attack. Once the big cat has selected its victim, it rarely shifts its gaze from them even when creeping around into another position.

But cougar attacks are increasing. In the last hundred years (1912 to 2012) 201 attacks occurred, with 124 of those—sixty-two percent—taking place since 1990. Granted, early attacks sometimes weren’t recorded. But according to the data available, there was a minor spike in the 1950s (12 attacks compared to 5 the previous decade), perhaps due to some states and provinces ending or phasing out bounty hunting. There was a sharp rise in the 1970s and 1980s with 19 and 25 attacks each decade. And then a huge jump in the 1990s with 62 attacks, and another 58 taking place between 2001 and the end of 2012.

Cougars attack people for many reasons, with each cat, person and set of circumstances creating a unique situation. The cougar might be young, old, sick or starving. A high density of cougars in an area or a low prey population can cause aggression as males compete for territory and all cougars compete for food. Cougars will also act aggressively if they feel their prey carcass is threatened and females will respond the same way if they have cubs. Cougars that prey on livestock or pets may become accustomed to the human environment and begin to view people as another form of prey, and the quick movements of a jogger, mountain biker or child may trigger the cat’s chase/kill instinct. Cougars continually run off their kills by wolves may seek other sources of nutrition.

Because attacks on humans are so unusual, there is speculation that some cougars experience chemical changes in the brain, due to nutritional, genetic or other conditions, that affect their behaviour. Necropsies on some cougars that attacked humans revealed diseases such as rabies and feline leukemia.

Some believe logging affects cougar behaviour, too. “Deer do really well in old-growth forests where there is a healthy understory,” explained Danielle Thompson, a wildlife biologist with Pacific Rim National Park. “They also do well in recently logged areas where there is lots of lush, new growth. It’s during the in-between stage when tightly spaced trees grow back and choke out the undergrowth that they don’t do well. That’s when deer are forced out of their habitat and concentrate in marginal habitat near and in human use areas where they can find food. And despite their natural wariness, cougars will follow.

“Changes to the landscape such as extensive logging roads and more trails also has an impact on wildlife and alters their behaviour,” she added. “It’s energetically costly for an animal to move through a dense understory. So they travel on the same roads, trails and beaches that people do, creating an overlap of time and space that increases the chances of an encounter.”

One question often debated is whether cougars possess an innate fear of humans or if it is learned. From reading many accounts, it appears that cougars were more wary of humans in the past. In fact, they were commonly considered cowards who only attacked people if they were sick, injured or defending their cubs. In his 1917 book The Panther and the Wolf, Colonel Henry W. Shoemaker noted: “The woods [of Pennsylvania] teemed with them . . . Almost every backwoods kitchen had a Panther coverlet on the lounge by the stove. Panther tracks could be seen crossing and re-crossing all the fields, yet children on their way to school were never molested.”

But a lot has changed since the early days of the twentieth century. In the 1970s people began moving out of urban areas and onto rural or semi-rural properties. Some wanted to “get back to the land,” plant big gardens and raise chickens, horses or a cow or two. Others were looking for a quiet neighbourhood complete with star-studded skies and a nice view. An acre or more, often with dense vegetation and adjacent to similar properties or land in its natural state, provided privacy and more opportunities to see wildlife. The next decade brought an increased emphasis on the benefits of physical fitness, and the manufacturing of lighter-weight, better-functioning mountain bikes in the 1990s meant more people were hiking and biking in rural and wilderness areas than ever before. Also, improved transportation infrastructure meant many city dwellers were only a short drive away from national parks and other wild places. Cougar hunter George Pedneault noticed a change on Vancouver Island when pickups and campers became commonplace. “Around the 1970s, the island really opened up with logging roads into rural areas,” he said. “People had to walk in before, but now they can drive in and park their camper or travel trailer next to a nice lake.”

Some, like Dave Eyer, don’t think cougar attacks on humans are escalating just because there are more people in the woods. Eyer has a degree in biology and has worked as a naturalist, hunting guide and trapper. In his twenties his work in the adult education field took him to the Arctic, where he spent time with Inuit hunters observing the prey–predator interactions between caribou and wolves and between seals and polar bears. That experience, plus bear awareness and safety books by Stephen Herrero and Gary Shelton, reinforced his interest in large carnivores.

Since 1985, Eyer and his family have lived on 65 hectares (160 acres) an hour’s drive northwest of Clinton, BC, where seeing wildlife is as common as sitting down to dinner each evening. As owner-operator of Eyer Training Services, he’s taught a variety of safety and outdoor education courses. In 2000, he added a bear and cougar encounter program for industry and government field workers, which is now a required course for many employees. He offers a similar workshop for people who spend recreational time in the woods or who live in rural areas.

“The more people in the bush theory would result in more accidental encounters, which could lead to more attacks,” Eyre said. “That may be true for bears as the majority of grizzly bear attacks are defensive. But most cougar attacks are predatory. The majority of people are attacked from behind, they’re not accidently bumping into a cougar. In BC between 1983 and 2005, thirty-four percent of cougar attacks occurred in developed areas where normal human activity regularly occurs, so cougars are approaching places where people are.”

By developed areas Eyer is referring to houses, schools, playgrounds, logging camps, commercial campgrounds and youth camps. His statistics for cougar attacks on humans in British Columbia from the early 1800s to 2005 indicate that ninety-three percent of the attacks were either predatory or possibly predatory. He suspects that cougar and deer biology and genetics play a role in why cougars attack humans. Plus the fact that people now treat cougars differently than they did previously.

“I believe the unrestricted shooting, trapping and poisoning of cougars during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries seriously suppressed the cougar population,” Eyer said. “Many cougars were eliminated and the survivors took great care to avoid people. That’s probably why there were so few cougar attacks on humans before the 1950s.

“There were most likely always some cougars that would attack humans if given the opportunity,” he continued. “But up until the 1960s, most hunters, guide outfitters, ranchers, pioneers and government workers carried firearms in the bush. Cougars were thought of as vermin and shot on sight. There are many stories of cougars approaching people but no contact being made. That’s because the rifle was handy, loaded and quickly used. The cougar was either killed or ran away and learned not to hang around humans. There’s been a cultural shift in how people respond to cougars. Few people carry firearms anymore and a significant proportion of urban people who hike are naively unaware about the dangers of large predators.”

Bear expert Gary Shelton echoes those sentiments in his three books: The Bear Encounter Survival Guide, Bear Attacks: The Deadly Truth and Bear Attacks II: Myth & Reality. “In the early part of the 20th century, people lived off the land,” he wrote in The Bear Encounter Survival Guide. “They raised food and kept livestock. In those days people didn’t tolerate carnivores close by. They couldn’t or their crops and livestock would be destroyed. Then in the ’70s and early ’80s that culture changed. It became easier to grow food in large scale operations and ship it to outlying areas. So people were no longer competing with nature for their food and carnivores weren’t such a problem. That meant less bears and cougars were shot and over time their populations have increased.”

The majority of attacks on humans are by young cougars, but that isn’t always the case. And they aren’t always sick or starving either. There are accounts of two- to three-year-old healthy cougars, some that had recently eaten, attacking people. These animals fall within the borderline age of young adults that were perhaps still figuring out how to survive. But mature cougars in good condition also attack humans.

Cougars prefer treed, brushy areas or broken ground so they can stalk their prey, sometimes for hours. Many people don’t even realize a cougar is nearby until it attacks them.

On May 16, 1988, the badly mauled body of a nine-year-old boy was found in the Catface Range just north of Tofino on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Two days later a four-year-old, healthy male cougar was shot in the area. Examination of both bodies confirmed the cougar killed the boy. Thirty-year-old Frances Frost was killed around 1:00 p.m. while cross-country skiing in Banff National Park in Alberta on January 2, 2001. There was evidence that the healthy, eight-year-old male cougar found standing over her body had stalked her for some distance. One year later, a healthy three- to four-year-old male cougar that had recently eaten attacked sixty-one-year-old David Parker a short distance from his home in Port Alice, BC.

Frances Frost was moving faster than a walk, which may have triggered the cougar’s chase/kill instinct. David Parker had ducked under an overhang to shelter from a rain squall so he might have appeared vulnerable. No one knows what the young boy was doing but he was a small human. The one thing they all have in common is that they were alone when they were attacked or killed by a fit, mature male cougar.

In a paper presented at the 3rd Mountain Lion Workshop, held in Arizona in 1988, Dr. E. Lee Fitzhugh stated that “Mountain lions are large, strong predators and can treat people as prey.” His theory proposed that cougars learn to view humans as prey by watching another cougar attack a human, by seeing a human after a botched deer kill and attacking the person instead, or by having their kill instinct triggered by seeing a person exhibit prey behaviour such as moving quickly.

In “Managing with Potential for Lion Attacks Against Humans,” the wildlife biologist speculated that cougars may encounter an unknown species on numerous occasions before deciding it is prey. He noted that felines are programmed to attack anything that moves quickly away from them and mentioned personal knowledge of cougars following people from a distance while they were on foot or horseback and considered this type of behaviour a possible form of habituation.

“We understand through ecology that some predators engage in prey switching, moving from their primary prey, such as deer, to an alternative such as horses or sheep,” explained Marc Kenyon of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Not every lion, but some may consider people as potential prey. It depends on a lot of things: their nutritional needs at the time, their hunting experience, the availability of traditional prey. I believe every lion that attacks and feeds on a person has made the decision that humans are a potential prey item.”