There is a history of cougars attacking and consuming people . . . and it happens more on Vancouver Island

than any other place in North America.

—Bob Hansen, wildlife specialist, Canadian Geographic

Cougars are mysterious, magnificent creatures. Their stealthy nature allows them to pass through forests, deserts and urban neighbourhoods unseen and to sneak up on their prey without a sound. They are built to kill, and do so extremely well. But while the majority of cougars prey on deer and other animals, some attack humans. And in certain regions of Canada and the US, this happens much more frequently than in other locations.

Around 7:00 p.m. on August 1, 2002, David Parker was walking to the Jeune Landing industrial log-sorting depot a couple of kilometres (a little over a mile) from his home in Port Alice, BC. Located on northern Vancouver Island, the community has about eight hundred residents, most making a living in the logging industry or working at the pulp mill. Parker’s a regular walker and he particularly enjoyed taking this route on a summer evening. “You often see a really nice sunset from the dry-sort,” he said.

About a half an hour into the outing a rain squall blew in off the inlet. Parker’s short-sleeved shirt and jeans didn’t offer much protection so he ducked under a rock overhang and leaned back to wait the rain out. The next thing he knew, a cougar’s fangs were less than an arm’s length from his head. “Just before the attack I heard a soft plop plop sound like snow falling from a tree limb and striking the ground,” he said. “It was the cougar’s paws on the rock above me. As soon as I saw it, I instinctively raised my left shoulder to protect my neck.”

The force of the impact knocked the sixty-one-year-old face down on the gravel logging road, shattering his left temple, eye socket, cheek bone and jaw. He felt a floating sensation, then the pain of his scalp being shredded. A piece of it fell forward and blood dripped from his hair. “The cougar was on my back so I put my hands behind my neck to protect it,” Parker explained. “Then the cougar bit into my skull—the pressure was enormous—it was crushing, scooping out a piece of my head. Despite the excruciating pain, I knew if I didn’t do something soon I’d die.” He reached for the folding knife in the sheath on his belt. But as soon as his hand moved, the cat went for his neck. Realizing his mistake, Parker snapped his head to the side. The cougar bit into the right side of his face, peeling it back from his nose to his ear, which was left hanging by a thread of skin. His eye, along with some attached muscles and socket pieces, dangled on his check by the optical nerve. “At that moment I thought my life was over and decided to inflict as much damage as I could.”

Despite having his head on the down side of the hill and a forty-five-kilogram (one-hundred pound) cougar on his back, the retired millworker used his arms to lift his body up. “I just kept pushing, pushing as hard as I could against the gravel,” he said. “Finally I got my knees under me and pushed back as hard and fast as I could.” As they toppled backwards, the cat scampered clear, then charged. Parker swivelled on his butt to kick it in the face. “It came at me again and again, it was relentless,” he said. “My feet were bruised from kicking it so hard. I was yelling obscenities and it was making a yowling noise.” Once when the cougar swatted at him he grabbed it by the forepaw but it quickly twisted free. Another time it ran between his legs and he gripped it in a scissor hold but it squirmed loose.

Then Parker grabbed the cougar again. “I got a grip just back of its forelegs, put my chin into its chest and held on,” he said. The cougar thrashed and squirmed. “He hated being held like that but I squeezed as hard as I could. I just kept pushing and squeezing until the cougar was standing on its back toes.” But as soon as he eased up on the pressure, the fight resumed. Parker knew he had to go for his knife again. This time he managed to get it out but lost it in the scuffle. “The cougar was on me and I was trying to hold it away,” he said. “Then I felt the smoothness of the knife under the back of my right hand and grabbed it.” He let go of the cougar to open the folding knife. And dropped it again. The fight continued. When Parker found the knife a second time he knew it was his last chance.

Despite the excruciating pain and pressure of a full-grown cougar’s canine teeth puncturing and crushing his skull, David Parker knew he had to fight back or die. Photo by Paula Wild

While Parker was opening the knife, the cougar dug its right foreclaws into his shoulder. Parker swung the blade at the paw, stabbing himself instead. “I couldn’t really see—my left eye was full of blood and dirt from the cougar bite and wrestling around on the ground, and my right eye was bobbling uselessly on my face,” he said. “With my right elbow on the cougar’s chest I took two quick jabs towards its head.” By luck, he stabbed it in the jugular vein each time. The cougar went wild. Even with blood spurting from its neck it still fought. Parker hugged the cat to him as hard as he could in an attempt to minimize the damage. “When it stopped moving I let go,” he said. “But it jerked to life again so I had to hold it for at least another minute.”

When Parker stood up he saw two huge pools of blood on the ground: one his, the other the cougar’s. He threw the knife at the cat and staggered a kilometre and a half (a mile) down the road toward the dry-land sorting depot. It was closer than home and he could hear equipment operating. He went to the machine shed where some fellows had been working the evening before but it was locked. Farther away someone was cleaning up the grounds on an excavator. By this time it was getting dark. Parker threw a chunk of wood at the machine to get the driver’s attention. Jeff Reaume took one look at the blood-soaked man and sped him to the Port Alice Hospital.

Parker and his wife, Helen, spent the next two years visiting hospitals as he underwent extensive reconstructive surgery. He knows if he had lost the sight of both eyes on the logging road, or not found the knife the second time, he wouldn’t be around today. The couple still lives in Port Alice, and Parker goes for walks most days but never outside the village alone.

Trying to get the folding knife (shown at bottom) open while a cougar attacked him almost cost David Parker his life. Now he doesn’t even go into his own backyard without a fixed-blade knife (top) in a sheath on his belt. Photo by Paula Wild

“Everything has changed,” he said. “My right eye doesn’t work and I have trouble with my right ear and nostril. I have three steel plates in my head and a big dent in my skull where the cougar bit me.” Parker never leaves the house—even to go into the backyard—without a fixed-blade knife on his belt. “All my injuries occurred before I got the knife out,” he explained. “The conservation officer told me I was lucky the blade was so sharp. He said most knives aren’t sharp enough to cut through a cougar’s hide.”

As for the cougar, a post-mortem exam revealed it was a healthy three- to four-year-old male that had eaten within twelve hours of the attack. Although Parker’s a tall, fit man, he was alone, and ducking under the rock overhang may have made him appear smaller and thus more vulnerable. Healthy, mature cougars attack humans less frequently than young cats but, due to their size and hunting expertise, the encounters are more often fatal. The fact that a 77-kilogram (170-pound) man, unarmed for much of the altercation, was able to fight off an animal capable of taking down a full-grown elk is a true testament to Parker’s resourcefulness and will to survive.

Soon after the attack, Parker watched walkers pass his home armed with knives, bear spray and walking sticks. But ten years later few carry any defensive weapons. “People forget,” he said. “They think it won’t happen to them. But my wife and I, we never forget. Not even for a day.”

In 2002, Parker had lived in Port Alice for twenty years. He knew cougars were around but had only begun carrying a knife eighteen months before the attack. And he’d done so because of what happened to John Nostdal on February 8, 2001. Around 9:30 p.m., the Seattle resident was riding his bike from the Port Alice townsite back to his boat near the pulp mill when he noticed a clicking noise similar to fingernails tapping on a hard surface and thought something was loose on his backpack. Then a heavy weight hit the fifty-two-year-old from behind, knocking him to the ground. Suddenly the big, strong tugboat owner was fighting for his life. The cougar kept trying to bite his neck but Nostdal’s jacket and backpack, which had his yoga mat in it, were in the way.

Elliot Cole was driving home from the mill when he saw a man on the ground covered in blood. Initially he thought it was a biking accident. Then he saw the cougar. Without thinking, Cole leapt out of his truck and began yelling and hitting the cougar with a bag of binders. When that didn’t work, he punched the animal in the head a few times. But the cougar wouldn’t give up. Cole grabbed Nostdal’s bike and used it to pin the cat to the ground while yelling at Nostdal to get in the truck. Cole punched the cougar so hard its head bounced off the pavement and he joined Nostdal in the vehicle. Even then the cougar held its ground, only leaving when Cole stomped on the gas pedal. Nostdal is convinced that his backpack, his yoga mat and Cole’s timely appearance and brave actions saved his life. Wildlife officials believed the cougar might have been the same one that had recently survived being hit by a car, confronted a local resident and killed several pets.

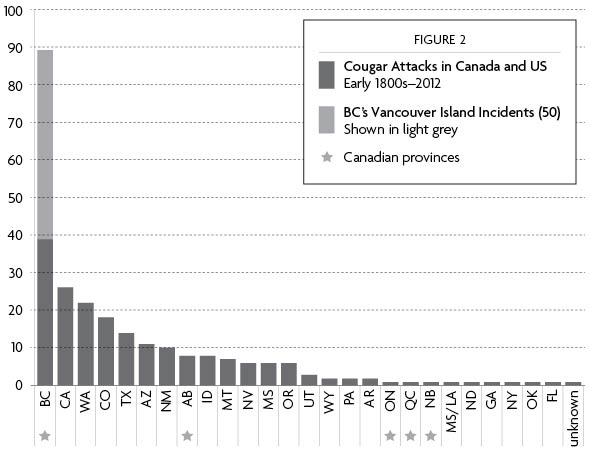

Overall, cougar sightings are infrequent, encounters rare, and attacks extremely so. Yet it seems like everyone who has lived on Vancouver Island any length of time has a cougar story to tell, and often two or three. Most are of fleeting glimpses of a long tail arcing across the road in front of a vehicle late at night. That’s a thrilling moment. But other stories are filled with emotional and physical trauma and sometimes death. In the last two hundred years, 89 of the 252 documented cougar attacks on humans have occurred in British Columbia. And 50 of those took place on Vancouver Island. That’s pretty amazing considering that the island is just over three percent of the land mass of BC and less than one percent of current cougar habitat in North America. In comparison, the next highest number of attacks, 26, took place in California.

At the end of 2012, the B C Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations estimated there were six thousand cougars in the province, including six hundred on Vancouver Island. If those ratios were more or less constant over the years that would mean a mere ten percent of the BC cougar population was responsible for fifty-six percent of the attacks in province.

Chart prepared by David G. Eyer

As well as having the highest number of attacks of anywhere in Canada and the US, Vancouver Island has the highest density of cougars. And that’s despite extensive hunting. Some say cougars on the island have been the most aggressively hunted of any state or province. In Island Gold, Dell Hall noted that sixty percent of the cougars killed in BC during the bounty years came from Vancouver Island. After the bounty was dropped and cougars became a big game animal, forty-two percent of cougars killed in BC (as of 1990) were from the island. Obviously, the big cats have been able to hold their own and even increase their populations at times.

BC has some of the biggest cougars in the world—some weighing more than 225 pounds—but Vancouver Island has always had a reputation for the most aggressive ones. “West Coast cougars have a particularly nasty disposition,” Hall wrote. And in Panther, Roderick Haig-Brown noted, “The black striped northern Vancouver Island cougars were the ones hunters most feared.”

The number of attacks on the island vary from year to year but what’s interesting, in a macabre sort of way, is where they’ve taken place. David Parker’s 2002 encounter was the second incident in Port Alice within two years. And the sixth to occur between 2001 and 2005 in what Vancouver Island residents call the North Island, loosely defined as the area north of Campbell River and Gold River. Over the last two hundred years the North Island has been the site of thirty-one cougar attacks. That is twelve percent of all incidents in Canada and the US. And the attacks weren’t just randomly scattered across the landscape. At Fort Rupert, a twenty-minute drive south of Port Hardy, one cougar killed twelve girls. In the vicinity of Port Alice and nearby Lake Victoria there have been seven attacks. The Port Hardy area, Gold River and Holberg have experienced three each and Quatsino Sound, Kyuquot and Zeballos have had two attacks each. Eight other locations have experienced one attack and there have been numerous occasions where cougars have stalked people and pets.

Beginning in 2011 the high frequency of cougar–human altercations shifted to the lower portion of the island. That year a cougar stalked a teenager in Nanaimo, and then over the Labour Day weekend a two-year-old healthy cougar was shot at Park Sands Beach Resort near downtown Parksville and an eighteen-month-old cougar was killed at Goldstream Park, just north of Victoria. Both young animals were brazenly watching crowded campgrounds in broad daylight and showed no fear of humans, even when people shouted and threw rocks at them. A cougar killed a horse in the Comox Valley on the central east coast of Vancouver Island, and a woman in a rural area of Nanaimo found a cougar feeding on a deer in her backyard. Cougar sightings in the greater Victoria region included a kindergarten class that had to abandon their walk when they came across a cougar feeding on a kill.

Communities on the western side of the island also had some tense situations. In 2011, an eighteen-month-old boy was attacked at Swim Beach in the Kennedy Lake day-use area of Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. After the grandfather and a family friend rescued the boy, the cougar circled his four-year-old sister. A woman was stalked and threatened while jogging near Ucluelet. Farther up the peninsula, a man who broke off from a group walking on Cox Bay Beach was stalked and cougars were seen in the middle of the day at the Long Beach parking lot and the Tofino Crab Dock. The following year, a seven-year-old boy was attacked at Sproat Lake near Port Alberni in August and a month later a thirty-eight-year-old man was attacked at an Ahousaht gravel pit located on Flores Island, northwest of Tofino. Altogether, twelve Vancouver Island communities have been the site of more than one cougar attack in the last century.

Vancouver Island isn’t the only place that seems to have unusually aggressive cougars. Like most of Canada and the US, California went through an intense bounty-hunting period, followed by the regulation of mountain lions as big game. In 1990 residents voted in favour of Proposition 117, making mountain lions a “specially protected species.” According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Proposition 117 makes it “illegal to take, injure, possess, transport, import, or sell any mountain lion or part of a mountain lion.” They can only be killed if a depredation permit is issued for a specific lion attacking livestock or pets, to preserve public safety and to protect listed (endangered) bighorn sheep. A new policy allowing conservation officers more options to deal with potential human conflict was introduced in 2013. Aside from Florida, California is the only jurisdiction in the US or Canada to protect mountain lions to such an extent.

As of this book’s publication, the most recent serious mountain lion attack in California took place on January 24, 2007. Fortuna, California, residents Jim and Nell Hamm were near the end of a sixteen-kilometre (ten-mile) trek in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, half a day’s drive north of San Francisco. It was close to 3:00 p.m. and starting to get dark so they turned onto a shortcut to the parkway trailhead. “I heard a couple of little noises and then something louder like a bike behind me on the gravel path,” recalled Jim. “I turned and a mountain lion was in mid-flight, paws straight out, coming right at me.” The seventy-year-old quickly lowered his shoulder and turned to the side. The lion flew over him, turned and leapt at Hamm’s upraised arm. “The lion had its teeth clamped on my arm and was dangling from it with all four paws in the air trying to get me,” he said. “I tried to punch it but the cat was heavy and I fell down.”

With Jim face down on the path, the lion ripped a piece of his scalp off. “Jim didn’t scream,” said Nell, who was about six metres (twenty feet) up the trail. “It was a different, horrible sound.” When the sixty-five-year-old spun around she saw her husband laying on the trail with his head in the lion’s jaws. “I don’t remember looking for it but the next thing I knew, I was holding a big redwood branch about four inches thick and eight feet long,” Nell said. “It was winter so the log was wet and heavy. Even with the adrenaline flowing, it was all I could do to lift it.” Afraid of hurting Jim, she hit the lion over and over on its torso, screaming “Fight, Jim! Fight!” with every blow.

“The branch was so heavy it bounced off Nell’s legs every time she hit the lion,” Jim said. “Her legs were black and blue afterwards but the cat never flinched.” Jim shifted his body a bit, stuck his fingers in the lion’s nose and twisted as hard as he could. “It let go of my head and grabbed me by the lips. We were teeth to teeth and I could see every cell in its eyes, they went from round to elongated. Then it shook its head, tearing my lips apart from my nose to my chin, exposing a large part of my mouth.” When the lion went back to licking his head, Jim shoved his thumb in its eye with all the force he could muster. “A cat’s eyes move around in the sockets and my thumb went sideways hitting bone. That’s when I told Nell to get a pen out of my pocket and stab the lion in the eye right through to the brain.”

“When Jim started talking it was a relief because I knew he was still alive,” Nell remembered. “I thought the pen would go in easily but after about an inch it bent so I went back to hitting the cat with the log. I just knew it was going to kill Jim.”

The lion kept biting Jim’s skull and trying to shake him by the neck but his backpack was in the way. In desperation, Jim stuck his right hand in the cat’s mouth. “It really hurt but its tongue was rubbery and I could get a good grip on it,” he explained. “I know if you hold a dog’s tongue they can’t do anything. But that made the lion really mad so I had to release and grab again. Then it got loose and went back for my head.”

“Jim told me to do something different,” said Nell. “So even though I was worried about hurting him, I took the sharp end of the log and rammed it in the lion’s face.” The cat was holding onto Jim with its eyes closed, apparently waiting for him to die. But Nell’s new tactic caused it to open its eyes and let go of Jim. It crouched two metres away (six feet) with its ears pinned back, glaring at Nell. “Jim’s blood was all over her muzzle and chest,” she said. “I knew she was going to attack so I raised the branch over my head and screamed as loud as I could, “She’s got me, Jim! She’s got me!” The lion hesitated then casually walked off into the ferns.

The fight had lasted about six minutes. Nell tried to get Jim up but he was bleeding profusely and in shock, and kept muttering that he was tired. But Nell knew that having so much blood around meant the cat would be back. Somehow she got Jim on his feet and they headed to the trailhead four hundred metres (a quarter mile) away. “Part of my scalp was left on the ground, the rest hung from my head,” Jim said. “At one point we managed to jog a bit and I could feel it bouncing on my shoulders.” When they reached the trailhead Nell laid Jim down and gathered some logs in case the lion followed them. Their cellphone wouldn’t work so they had to wait for someone to come by. Jim’s head and face were so badly mauled Nell couldn’t bear to look at him.

Jim had lost a lot of blood and was treated for wounds to his head, hands and legs. His lips had to be sewn back together and a thin slice of muscle with a skin graft was needed to cover the large section of scalp that had been torn away. His wounds became infected and he nearly died. At the attack site, wildlife officials killed two lions. The larger of the two, a healthy but skinny two- to three-year-old female, had human blood under her claws.

The Hamms had always been active and athletic and they’d previously discussed what to do in the event of a mountain lion attack. But most importantly, like David Parker, they never gave up. Officials told them that if Jim had been by himself, he probably would have died. Nell is certain neither one of them would have survived if the attack had taken place earlier in the day. “Jim couldn’t have gone very far and I never would have left him,” she said.

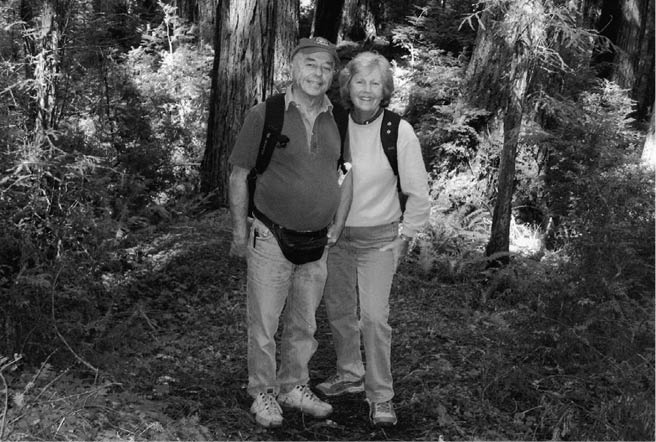

After a mountain lion nearly killed Jim Hamm, he and his wife, Nell, were afraid to go on the long-distance hikes they loved. But over time they conquered their fear and now encourage others to be aware and alert and to carry bear spray and knives when in lion habitat. Photo courtesy Jim and Nell Hamm

Most mountain lions go to great lengths to avoid humans but when they do attack, it can be physically and emotionally devastating. In addition to Jim’s long physical recovery, the Hamms had to deal with their fear. “During the attack I knew I was going to die,” Jim said. “Afterwards, I was afraid to go outside. I thought about moving to the city but a person isn’t necessarily safe there either. It took a lot of willpower and determination to go outside—our backyard borders onto redwood forest—but I didn’t want to huddle in the house the rest of my life.”

The Hamms have resumed taking long-distance hikes several times a week and have even revisited the site of the attack. “We’re not afraid now, just aware,” Jim said. “We both carry bear spray and knives. And we’ve spent a lot of time informing people about cougar attacks and encouraging them to be prepared and not hike alone.”

California’s earliest verified mountain lion attack occurred in 1870, and there were a total of nine by 1944. Then there was a stretch of forty-two years before the next one. That took place in Caspers Wilderness Park in Orange County, just outside of San Juan Capistrano in southern California. At about 2:00 p.m. on March 23, 1986, Laura Small was looking for tadpoles in a stream with her mother, Susan. The family had visited the park often and Laura’s dad and nine-year-old brother were nearby. Suddenly, the five-year-old disappeared without a sound. Susan had glimpsed a “muscular animal” dragging her daughter away but it took a few moments for her to comprehend what had happened. Then she screamed as loud as she could. Laura’s dad and brother came running, as well as some other hikers. They found Laura in some bushes with the mountain lion standing over her. One of the hikers brandished a stick at the cat while her parents grabbed her and ran.

Laura was in bad shape. In Cat Attacks: True Stories and Hard Lessons from Cougar Country, Jo Deurbrouck and Dean Miller wrote, “Her scalp, nose, and upper lip hung loose. Her right eye had been sliced open. Her skull had been crushed so severely that a portion of her brain had been liquefied by the pressure.” Immediately after the attack Orange County closed Caspers Wilderness Park for a while and a two-year-old, healthy male lion was shot near the site of the incident. The Smalls successfully sued the county, citing numerous daytime sightings of mountain lions and aggressive behaviour by two cats during the months preceding Laura’s attack, but no warning signs posted at the park to warn visitors. Then, on October 19 of the same year, six-year-old Justin Mellon was hiking with his parents and sister, as well as his uncle’s family, in the park. Justin stopped to tie his shoelace and a mountain lion hit him so hard it knocked him out of his shoes. His dad, Tim, rushed the cougar with the fixed-blade knife he carried in a sheath. The cat dropped the boy but kept its eyes on him while his mother carried him away. Tim and his brother-in-law waved their arms in the air and yelled until the mountain lion walked away.

The Mellons also sued Orange County and settled out of court. This time the park was closed for three months. When it reopened, children, accompanied by adults, were only allowed in the picnic areas adjacent to the paved roadway. Warning signs about mountain lions were posted in prominent locations and updated after each sighting. Visitors were even asked to sign waivers before entering the park. Only a few declined to do so and left. Ten years later, in December 1997, children were once again allowed full access to the park. Within two weeks a group of hikers consisting of women and young children were charged by a mountain lion, which was later destroyed. Orange County was in a difficult position. No one wanted to close the park to children permanently and Californians were unlikely to condone the killing of all mountain lions in the area. As of 2013 the park has remained fully accessible to children and there have been no further incidents.

In 2004, attacks in Whiting Ranch Wilderness Park, about a thirty-minute drive from Caspers Wilderness Park, made the news. Thirty-year-old Anne Hjelle was mountain biking with her friend Debi Nicholls on Cactus Ridge Run on January 8 when a mountain lion knocked her off her bike around 4:30 p.m. The fitness instructor and former Marine fought back with everything she had but said afterward the lion possessed “the strength of ten men.” She didn’t know that just a short distance away and within the past twenty-four hours the cat had killed and partially eaten Mark Jeffrey Reynolds, a thirty-five-year-old competitive mountain bike racer.

The lion tried to bite the back of Hjelle’s neck but when her helmet got in the way the cat shifted its teeth toward the side of her head. The mountain lion bit her face and neck, ripping her left ear from her skull and folding the left side of her cheek over her nose. As the mountain lion dragged Hjelle into the bush she heard Nicholls screaming and then felt her friend grab her leg. The forty-seven-year-old played a deadly game of tug-of-war with the mountain lion as it pulled both women farther from the trail. Then five other cyclists heard the ruckus. They threw rocks from the trail and when one hit it in the face, the lion released Hjelle but remained nearby. Hjelle was severely mauled but survived thanks to her friend’s determination. A healthy two-year-old, 55-kilogram (122-pound) lion was later killed in the area. Tests revealed that it was responsible for both attacks.

But perhaps the spookiest series of California mountain lion skirmishes took place 121 kilometres (75 miles) away from Whiting Ranch Wilderness Park. In 1993 and 1994, mountain lions in Rancho Cuyamaca State Park chased horseback riders, bit a ten-year-old girl, mauled a dog, threatened three cyclists and almost attacked a three-year-old boy. In the last incident, when five park officials, accompanied by two dogs, found the cat they said it showed no fear of humans. Some of the problem mountain lions were juveniles and one had a deer carcass stashed nearby. But it was a healthy 59-kilogram (130-pound) male about five years old that killed fifty-six-year-old Iris M. Kenna on December 10, 1994, as she hiked in the park alone.

The lions in Rancho Cuyamaca Park were getting such a bad reputation that even park rangers were wary of walking the trails alone. People living nearby felt that going to the park meant entering the food chain. Throughout the 1990s there were eighteen occasions when lions acted aggressively toward humans, including two attacks and one fatality. Between 1993 and 1998 wildlife officials killed twelve lions due to public safety concerns. Park maps even carried warnings that Cuyamaca lions were known to be unusually aggressive. But that didn’t deter people from enjoying the tranquillity and beauty of the area.

Lucy Oberlin had been running in the park for seventeen years when she encountered a mountain lion in August 1997. Oberlin and her long-time friend Diane Shields were halfway through a 22.5-kilometre (14-mile) run when they spotted the animal. As the cat trotted toward them the women yelled and waved their arms. When it didn’t stop, one of them used her pepper spray. The spray didn’t make contact with the cat’s face but did make the cat back up. The women edged over to a stand of small trees just as the lion charged. Oberlin waved a big stick and Shields threw rocks. For fifteen minutes the cat charged again and again, coming in fast and low then retreating. But each time it came a little bit closer. The women yelled constantly, even when talking to each other, but the lion never made a sound. Shields started to go into shock and Oberlin yelled at her to bring her around. Then the lion charged and didn’t stop. This time it got a squirt of spray in the face. It retreated but refused to leave. Slowly the women moved from tree to tree until they reached their vehicle in the parking lot.

Despite their ordeal, Oberlin and Shields still ran in the park. Four mountain lions were shot soon after their report and they figured their odds of seeing another one were extremely low. Just in case, Oberlin bought a .380 handgun to carry in her fanny pack. They avoided the trail where they’d met the cat for about a year. Then one day they included it on their run. They’d just passed a bunch of children at an outdoor camp when Oberlin saw a mountain lion across the river watching them. It shadowed them for half a kilometre (a third of a mile). Oberlin got her gun out but decided not to shoot unless it crossed the river. Even then she wasn’t sure she’d be able to use the gun due to their proximity to the highway. Once again the women made it to safety.

In 2001, in response to all the negative encounters, the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center was hired to study how mountain lions and people shared the landscape at Rancho Cuyamaca State Park. The team fitted lions with GPS collars capable of tracking their movements hourly and monitored visitor and lion use of trails. The results of the study were pretty much what researchers expected and consistent with research in other areas: male mountain lions covered larger distances than females and both sexes were most active on or near trails just before and after dawn and dusk and throughout the night. Those were the times when the mountain lions did most of their hunting. In general, the lions were farthest away from human activity areas during the daytime.

But they weren’t a great distance away. Eight out of thirty-three prey caches were located within 100 metres (109 yards) of a trail and two were within 300 metres (328 yards) of human structures such as campgrounds, park headquarters and residences for park employees. The study revealed that during the day adult lions could be expected to be within 100 metres (109 yards) of a trail nearly a quarter of the time they were within park boundaries. None seemed to be overly attracted to areas used by humans and none showed any aggression. In fact, the study indicated the lions were going out of their way to avoid people. The most likely time for altercations was around sunset when people were often still on the trails and the lions were becoming more active.

“It’s interesting that as soon as the study started there was no further aggression by mountain lions,” said Winston Vickers, associate veterinarian at the Wildlife Health Center. “Back in the nineties, in Cuyamaca and a park in Orange Country, there were several incidents of aggression. But nothing like that has happened in Cuyamaca since then and only one incident has occurred in Orange County. So to say mountain lions in either area are inherently aggressive does not appear to be accurate. That sort of activity is so rare. There can be a cluster of aggressive behaviour and then nothing for decades. Lions ignore people ninety-nine point nine per cent of the time—they just let us go by or sneak away.”

Just as individual cougars exhibit different behaviour, so can cougar populations within a particular geographic location. For instance, researchers studying mountain lions in New Mexico were able to approach within fifty metres (fifty-five yards) of lions on 256 occasions and only observed threatening responses 16 times. On the other hand, in the past 31 years there have been 14 mountain lion attacks in Texas, with 11 of them occurring in Big Bend National Park. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to tell if there is an aggressive cougar in an area. Cougars that attack humans are often killed and the problem goes away. But since there’s no way to tell if another aggressive cougar has recently moved in to claim the vacant territory, it is best to always be aware and prepared, especially in regions with a history of aggressive cougars.

The frequency of attacks and fatalities in different regions of western Canada and the western US is baffling in its diversity. In the last two hundred years, California has been the site of twenty-six attacks with eight fatalities, Oregon has had six attacks with no fatalities and Washington has had twenty-two attacks and two deaths. During the same time period in Canada, Alberta had eight attacks resulting in one fatality and of the eighty-nine attacks in BC, twenty were fatalities. The fifty BC incidents that occurred on Vancouver Island led to seventeen deaths. Out of the eight fatalities in California, five were adults. In contrast, out of the twenty fatalities in BC, nineteen were children and teenagers, seventeen of which were killed on Vancouver Island.

|

|

|

|

|

|

So why are there so many attacks on the island? Both California and Vancouver Island enjoy a temperate climate and have experienced large increases in human population. And improved infrastructure often means parks and wilderness areas are only a short distance away from residential areas. On the island, logging roads have made remote areas more accessible than ever before. But Vancouver Island has always had more attacks, even when there were fewer roads and humans. And in the United States, radio-collared mountain lions have been tracked in high-density human habitation and yet remained largely unnoticed and did not attack anyone. So something else must be going on.

Wildlife officials and scientists have various theories about the aggressive tendencies of Vancouver Island cougars. Information obtained from the B C Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations (FLNRO) noted there is a high density of cougars on the north end of the island but the habitat isn’t the best for deer and elk and there are lower populations of small prey such as raccoons. As the deer population fluctuates, cougars either have enough to eat or may become desperate enough to attack humans. The spike of cougar complaints in the 1990s coincided with a large crash of the local deer population.

The ministry also pointed out that the broken rock, steep ground and dense vegetation on the North Island provides prime stalking cover. Indeed, in places the brush is so thick a person could be right next to a cougar and not know it. Other factors FLNRO mentioned that may trigger aggression included a high density of cats resulting in more territory overlap, increased fighting among males and more adult males killing kittens, as well as a high population of wolves consistently running cougars off their kills. All these stressors have the potential to affect cougar health and behaviour.

Data from FLNRO also noted, “Aggressive cats are generally younger ones that have a hard time making kills and/or are severely emaciated. This can degrade their physical and mental health to such a point that they will take huge risks and hunt in the open, during broad daylight, in the same small area, say along a walking trail, where they have encountered pets in order to make a kill.” Yet, despite the higher attack statistics, FLNRO doesn’t believe Vancouver Island cougars are necessarily more aggressive than those in other locations.

Former Arizona cougar researcher Harley Shaw wondered if being on a relatively isolated island might have something to do with the aggression. Strong ocean currents, plus long distances to other islands or the BC mainland in many areas, could limit dispersal, thus creating a high-density population that must compete for territory and prey. Although some cougars could swim from island to island and possibly reach the mainland, they would likely be a minority.

Dave Eyer speculates that cougars in the relatively isolated gene pool of northern Vancouver Island may be genetically disposed to aggression. As well, poor prey habitat may force young cougars to seek other forms of prey and low prey populations may cause dominant males to increase their territory, thus forcing younger or weaker cougars to find a new range and possibly new prey.

Maurice Hornocker, often referred to as the dean of modern cougar research, agreed that genetics probably plays a role. “We have evidence that some population units are more aggressive than others just like some cities have higher crime rates than others,” he said. “I think a genetic link predisposes Vancouver Island mountain lions to aggression. Mountain lions on Vancouver Island and in Idaho, where I conducted most of my research, exhibit extremely different behaviours. It was rare for an Idaho lion to jump from a tree or attack a dog. Yet, when Penny Dewar was studying lions on Vancouver Island, it was a regular occurrence, they almost expected it. That reinforces my personal theory that individual mountain lion populations are predisposed to different behaviours.

“And,” he added, “the Vancouver Island cougar population is isolated and heavy hunting pressure over the years quite possibly has selected for aggressive behaviour—aggressive individuals simply survive.”

Another possibility is that some cougars may be losing—or never had—a fear of humans. When interviewed in 2004 by Mitchell Gray for a story for Canadian Geographic, Bob Hansen, Pacific Rim National Park’s wildlife–human conflict specialist at the time, stated, “We know cougars do view people as prey. There is a history of cougars attacking and consuming people. It’s a small but ever present risk, and it happens more on Vancouver Island than any other place in North America.”

The spring 2011 issue of Human–Wildlife Interactions presented another theory about particularly aggressive carnivores. Researchers Dave Mattson, Kenneth Logan and Linda Sweanor pointed out that man-eating carnivores are often specific individuals, prides or packs who attack people in a particular location. They also noted that this activity is learned and can continue for decades. That could explain why wolves often attack humans in Asia and eastern Europe but rarely do so in North America. And why tigers and other big cats in Africa and Asia attack people much more often than cougars attack people in North America. “These behaviours of other species elsewhere in the world serve as a cautionary tale and may partly explain the high concentration of cougar attacks on Vancouver Island,” the authors stated near the conclusion of their paper.

If that is so, an in-depth study of Vancouver Island cougars might be able to provide some answers as to what types of stressors may cause clusters of aggression, as well as lead to possible ways of disrupting the behaviour before it’s passed on to the next generation.