Oh the beautiful, splendid, supple, graceful, powerful, silent puma! I would rather watch and draw and dream about it than about any other thing.

—Charles Livingston Bull,

The Century: A Popular Quarterly, 1914

“The hounds were already loose, moving fast on the cougar’s fresh scent. The day was cold and clear and the sound of the dogs’ excitement filled the air,” Penny Dewar recalled in 2012. Back in 1973, she and her husband, Percy, had one rule when it came to winter hunting: never release the hounds after noon. But they’d passed the same spot an hour before and there had been no sign of cougar. Now there were large, round tracks most likely made by an adult male. “How far could he go?” they asked each other. And so the chase was on.

The couple wasn’t hunting for bounty or sport. They were conducting the first long-term, in-depth telemetry study of wild cougars in Canada. And they were doing so in the capital of cougar country, Vancouver Island. It all started in 1971 when the BC Fish and Wildlife Branch gave Penny two orphaned cubs. Hoping to replicate studies conducted with African lions, she planned to raise the cougars, release them on Cracroft Island, then follow and observe them. But at three months old the cubs were already too wild to handle, let alone bond with. On December 31, 1971, Penny’s future husband, Percy Dewar, knocked on her door. “If you want to learn about cougars, I’ll help you,” he said.

After the orphaned cougar cubs were placed at a wildlife reserve, Fish and Wildlife suggested the couple radio-collar cougars. Their study area stretched from the Strait of Georgia inland to Mount Arrowsmith and between the Nanaimo and Big Qualicum Rivers. All of their work took place in Percy’s guiding territory, most around Northwest Bay in the Englishman River watershed near Parksville. Their goal was to study the population dynamics and behaviour of cougars and determine how many were in the area.

The Dewars were an unlikely duo. When they met, Penny was a petite twenty-three-year-old with a degree in biology. Fifty-two-year-old Percy was extremely strong and fit and had spent most of his life in the bush logging, collecting bounty on cougars and guiding. “But he wasn’t just hunting,” explained Penny. “He was smart and paid attention to cougar and dog behaviour. Percy’s hounds were better trained than most poodles—they never chased deer or anything else, just cougars.”

And that’s what Lou and Blue were doing late this December 1973 afternoon. Percy ran ahead after the dogs while Penny moved at a slower pace, making notes and taking photographs. “The cougar was travelling,” she wrote in an unpublished article titled “Data.” “He climbed a high ridge, then down across gullies and through creeks, up another ridge, balanced over icy logs hanging in space, strode over snow and steep rock on and on. I climbed and crawled, slipped and trudged behind.

“Hours passed as well as the light and frail warmth of the sun,” she continued. “Wet from snow and effort, I was freezing. I’d lost the trail and Yaka, my Australian shepherd, had lost interest. Hours more searching, stumbling and cursing, circling and circling until I found an old road. Dark miles further I saw the fire. For thaw and signal, Percy had lit a pitch stump that flared the sky. He too had lost the trail, feared he’d lost me.”

With Yaka between them Penny and Percy stood on branches piled at the fire’s edge letting the heat melt the frost from their jackets and warm their bodies. “The flames were a wall above and before us,” Penny wrote. “We wondered how far the cougar would go before the hounds treed him. We knew they’d bay and bound beneath the tree until their voices died out then collapse in sleep. Once before we’d arrived to find a cougar snoring on a branch and the dogs below opening and shutting their mouths with not a sound coming out. We knew it might be days before we saw them again.”

Then something leapt through the flames and Yaka fell through the branches they were standing on. “Suddenly there was a cougar between us,” Penny wrote. “Percy and I looked at each other in surprise. The cat looked into our eyes, became frantic and ran.”

The Dewars returned the next day to read the story in the snow. When they’d started tracking the cougar they were deep in the woods, far from human habitation. But over the course of the night, they’d travelled to the edge of a neighbourhood—one that the hungry young cougar had staked out as a source of easy prey. “So, while Percy and the hounds chased one cougar, another had followed me and Yaka,” explained Penny. “We could see where it had lain on a log at the other side of the fire watching before sailing through the flames. Heedless of me it had stalked my dog and was locked in predator focus. It saw the dog as food and apparently did not notice the humans until it landed between us.”

The Dewars studied cougars from 1972 to 1978. For four of those years a 3.5 by 3.5 metre (12 by 12 foot) tent served as headquarters and home. It had cedar shake walls 1.2 metres (4 feet) high, a dirt and plank floor and a tarp roof that “flew when it blew.” Amenities included a bed, table and chair set and a bathtub the Dewars had carved out of a cedar log. The tent surrounded a very small travel trailer that served as a storage area, as it was mouse-proof. An airtight stove and a wood cookstove completed the furnishings. At one point the body count in the tent was two humans and fifteen dogs.

Biologist Penny Dewar listens at the telemetry tower outside the tent she shared with her husband, Percy, and up to fifteen dogs at a time while conducting Canada’s first long-term, in-depth cougar study in the 1970s.Photo by Su-San Brown, courtesy Penny Dewar

Lou, one of Percy’s bluetick hounds, was the star of the show. “She never made a mistake, all the dogs deferred to her,” said Penny. “We did most of our tracking during the summer. When it’s hot and dry scent can dissipate in seconds so we depended on well-trained dogs. Once, a cougar with cubs attacked Lou chewing her up around the head. When she recovered and took over as lead dog again we noticed we weren’t treeing any cougars. Percy ran after her one day and discovered that as soon as Lou got close to a cougar she turned back and all the dogs followed her.

“The cougars we encountered seemed to have an instinctive fear of humans,” Penny noted. “They’d climb a tree to get away from the dogs but one look at us and they often jumped. They’d leap from fifty or sixty feet up, land on the ground and then leap another thirty or forty feet and start running. They channelled the energy of the initial impact into the next leap.”

Even though it was cutting edge at the time, the telemetry equipment of the 1970s was mediocre at best. “If we hadn’t lived in the woods and devoted all our time to the research, we wouldn’t have learned anything,” Penny said. Even so, the Dewars were able to track and document cougar behaviour in a way that had never been done in the Pacific Northwest before. An unexpected discovery was the size of a cougar’s range. “Once a female had kittens her area shrunk to about five square miles,” said Penny. “Mature males roamed around one thousand square miles. There’d be a central portion within that where they spent most of their time and which they defended as their territory.”

The Dewars weren’t the first to observe cougars with a scientific eye. In the mid-1930s Frank C. Hibben received a grant from the Southwestern Conservation League in the US to study mountain lions, as the organization feared “this most colorful of American animals was becoming greatly reduced in numbers with little or no knowledge concerning them.” So Hibben spent a year hanging out with professional cougar hunters in New Mexico and Arizona. As research for his master’s thesis at the University of New Mexico, he studied the big cat’s prey, collected scat and talked to ranchers about livestock predation. In addition to his paper, Hibben wrote popular articles for magazines, as well as the book Hunting American Lions.

When it comes to cougar research, Maurice Hornocker’s work is the cornerstone of knowledge about the big cats. Over the course of his forty-year career, he’s studied wildlife worldwide, written books, made documentary films, published more than one hundred scientific articles and served on the board of many wildlife organizations. He also founded the Hornocker Wildlife Institute and later the Selway Institute, a non-profit society dedicated to wildlife research and education.

In the early 1960s Hornocker began the first ever long-term continuous study on mountain lions, pioneered the use of telemetry equipment on the big cats and discovered information that was instrumental in changing the animal’s status from vermin to big game species. “At the time, very little research had been conducted on mountain lions,” he said. “They’re very secretive so difficult to study and there were many misconceptions about them. My idea was to start from scratch, capture and mark all the lions in one location then recapture them over time to study them.”

The first winter he tagged and tattooed thirteen lions in western Montana. But the state still had a bounty and nine of his research subjects were killed by spring. So Hornocker shifted his study to an isolated region in the backcountry of Idaho. During the next ten years he captured sixty-four lions three hundred times. This was the first time anyone had really examined the sociology and ecology of the mountain lion and how the animal fit into the environment as predators of deer and elk. A major discovery was that they don’t just wander aimlessly but are strongly territorial. Another was that, instead of being a threat to big game, mountain lions kept ungulate populations in check. “Mountain lions have an important place in the environment,” Hornocker explained. “Ungulates have the ability to overpopulate and ruin the environment but mountain lions keep the whole system in balance. If the mountain lion population is stable, deer populations in the area will thrive.”

Hornocker’s groundbreaking research persuaded many western states to reclassify lions as big game, rather than vermin, and thus introduce regulations about hunting them. As public attitudes and the focus of governments shifted, studies on the carnivores increased. And while hounds are still the fastest way to tree a cat, more sophisticated telemetry equipment and the advent of global positioning devices that can document an animal’s movements as often as every five minutes have catapulted cougar research into a new era. Velcro is strategically placed to obtain fur samples, trail cameras record previously unknown journeys and DNA obtained from fur, scat or blood has the potential to identify individual cougars no matter what geographical or political boundaries they cross.

So what do we now know about cougars? More than ever before, but just enough to raise additional questions. The truth is no one even knows how many cougars live in any state or province, let alone in North and South America as a whole. But ongoing fieldwork continues to provide new information about the predator’s behaviour as well as insights into cougar–human dynamics.

Maurice Hornocker’s groundbreaking research in the wilderness of central Idaho during the 1960s was a major influence in the reclassification of mountain lions from bounty hunted vermin to big game species. In this photo he’s holding a forty-pound (eighteen-kilogram) cub that, along with its entire family, was tagged and tattooed as part of the study. Photo courtesy Maurice Hornocker

Witnessing a flock of sandhill cranes fly overhead one day while she was treeplanting in a remote BC location convinced Danielle Thompson that she wanted to learn more about wildlife and their habitats to ensure their continued presence on the landscape. Soon afterwards, she enrolled in the wildlife management program of the University of Northern BC. Now she’s a resource management and public safety specialist at the Long Beach Unit of Pacific Rim National Park Reserve.

In the mid-2000s research projects in the park examined the habitat needs of cougars, the impact of increasing visitor numbers and social reactions to large carnivores. As part of the WildCoast Project, Thompson analysed West Coast Trail visitor data and human–cougar interaction data from 1993 to 2006. “It’s hard to determine if people were seeing the same cat or different ones,” she said. “We know that in 2005 some siblings’ home range overlapped the West Coast Trail and that they had multiple interactions with different people. So there aren’t necessarily more cougars just because more activity is noticed.”

Thompson observed that cougar sightings on the West Coast Trail appeared to be cyclical with peaks of activity occurring every two to three years. It’s suspected this cycle may relate to the availability of larger-sized prey, such as deer, and competition with local wolf populations for prey. “What the research did show, however,” she said, “was that the majority of human–cougar encounters occurred during times when human use levels were low. This indicates that cougars are trying to avoid interactions with people.”

Students from the University of Alberta began studying cougars in the Central East Slopes and Cypress Hills regions of the province in 2004 and 2007. “There hadn’t been any cougars in the Cypress Hills for a hundred years,” noted Mark Boyce, professor and Alberta Conservation Association Chair in Fisheries and Wildlife at the University of Alberta. “Ranchers were anxious and angry as they were convinced they were losing livestock to cougars. At times they were so hostile I wondered if the student conducting the study could handle the pressure. The ranchers were also making accusations that Alberta Parks was releasing cougars into the area.

“That wasn’t the case at all,” Boyce continued. “The cougars were travelling up the coulees and Red Deer River Valley from the mountains in the west to repopulate their former range. But what was surprising was that out of the three hundred and fifty to four hundred cougar kills that took place during the study, not one was livestock. If an animal dies of disease or natural causes and is scavenged by coyotes some people will think it was killed by a cougar. But if you know what to look for and get to the carcass soon enough, it’s easy to tell if a cougar was responsible. The student conducting the study examined every cougar kill during the study and not one was livestock.”

Farther south, the Teton Cougar Project, based out of Jackson Hole, Wyoming, is examining the predator–prey relationships and demographics of cougars in the region, as well as how they’re adapting to the expansion of wolves and grizzly bears into their habitat. “We want to know everything about these cougars: what they eat, how they relate to each other and how wolves and grizzlies are affecting their lives and populations,” said Howard Quigley, the Teton Cougar Project director and executive director of jaguar programs at Panthera, the world’s leading cat conservation organization.

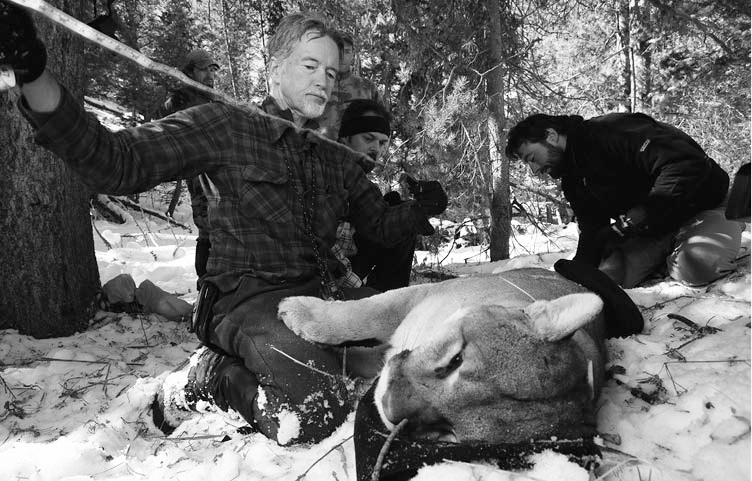

Advanced technology, such as the telemetry equipment being used by Howard Quigley, director of the Teton Cougar Project in Wyoming, allows researchers to better understand the movements and behaviour of cougars. Photo by Brad Boner, courtesy Panthera

Quigley became involved with cougars in a roundabout way. While working with bears in Tennessee, he was invited to study pandas in China then jaguars in Brazil. He met Maurice Hornocker while completing his doctorate at the University of Idaho, eventually becoming president of the Hornocker Wildlife Institute and working on long-term cougar projects in Idaho, New Mexico, Yellowstone National Park and now even parts of Latin America, where jaguars and cougars coexist.

“Technology has opened up a whole new world of studies,” he said. “Before we could only obtain DNA if we took a sample of blood from an animal. Now there are several ways to fingerprint individuals and determine who they’re related to, it’s very exciting. And GPS radio collars and high-definition trail cameras allow us to capture behavior that has never been seen before.”

Quigley recently watched a video of a male and a female cougar at an elk kill suddenly crouching, looking off camera and then running away. Shortly afterward, a big wolf appeared on the film. On another occasion, the Teton team discovered that F1, the female cougar profiled in the National Geographic video American Cougar, had lost two of her three kittens to a wolf pack. “Cougars adjusting to other large carnivores in the environment hasn’t really been studied in this detail before,” said Quigley. “It’s a rare opportunity in the field of science to witness these changes.”

Initially partnered with Craighead Beringia South, a wildlife research and education institute, the Teton Cougar Project began in 2001 and Quigley hopes it will continue through 2015 or even 2017. “With its collage of federal and private multi-use lands and protected areas, as well as amenities such as an airport, major highway and town, Jackson Hole is an ideal location for a long-term study like this,” he commented. “There aren’t many places where you can roll out of bed and be at the site of a cougar kill within forty minutes. It’s this type of long-term, intensive fieldwork that’s necessary to get the information we’re obtaining.”

The program’s proximity to wilderness resulted in Quigley becoming the first wildlife biologist to witness and report on a wild cougar adoption. After a hunter killed a female cougar with three young cubs in 2007, another female cougar, also with three kittens, adopted the orphans. Quigley believes the adopting female was the adult daughter of the dead cougar. “This kind of altruism is seen in many animals, including birds and humans, and is usually limited to those with close relations,” he wrote in an article for Panthera.

Another revelation occurred one winter day in 2012 when Teton team member Drew Rush went looking for F51. Following the VHF signal from her collar, he found the female and her two kittens. But he also saw two other cubs and another adult female cougar that weren’t collared. Then to top it off, a male cougar arrived and all seven of the big cats fed off the same kill. This was a shocker as it’s generally believed cougars are solitary animals, never travelling or eating together unless it’s a mother and cubs, young siblings recently out on their own or a mating pair.

This gathering of cougars raises interesting questions about how, when and why they might socialize with each other. And it turns out the 2012 meet-up wasn’t an isolated event. In their Vancouver Island study the Dewars radio tracked a get-together between two adult cougars that they suspected were mother and daughter. “They spent about thirty minutes together,” said Penny. “And what was interesting, was that they both had kittens but left them behind.”

Howard Quigley and field staff examine a cougar and record data such as weight, length and general health as part of the Teton Cougar Project in Wyoming. Photos by Steve Winter, courtesy Panthera

And when Brad Thomas set up a motion-sensor camera on a trail near Wenatchee, Washington, in February 2011, he got more than he bargained for. Thomas had never seen a cougar in the wild but his camera recorded a gathering of eight of them. Wildlife biologists examined the photo and declared it legit. Because mother and daughter cougars sometimes have close or even overlapping ranges, they speculated that it was a mother and her adult daughter, both with kittens. One of the biologists recalled seeing a 1960s photo of seven cougars crossing a bridge over the Stehekin River, also in Washington state.

As it turns out, cougars are full of surprises. During the bounty years poisoned bait was often used to exterminate wolves but wasn’t considered effective for cougars as they weren’t scavengers. But the research team at the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center has experienced incredible success using dead deer as bait for mountain lions. In 2001 a cougar even stole a dead deer out of their pickup. “I learned several lessons from that,” said Walter Boyce, wildlife veterinarian and professor at UC Davis. “The puma found the deer by smell, not sight; he wasn’t fazed by the streetlight and unnatural touch and smell of the truck and he ate and cached the carcass, treating the deer just as he would one he had killed himself.”

Between January 2001 and October 2003, the UC Davis team placed forty-four deer carcasses at twenty-three locations to study puma scavenging. Eight to twelve pumas scavenged at nearly half of the spots and some—ranging in age from eleven months to nine years—were captured seven times at scavenging sites. They took carcasses that were frozen, fresh or rotten. And all, except tethered carcasses, were treated as if it was the cougar’s own kill. One radio-collared puma frequently scavenged carcasses from a domestic livestock graveyard.

In 2005, the UC Davis team were radio collaring lions in the Santa Ana Mountains. They set a trap and a cat went in and tripped the door release within an hour. Boyce and the others were eating dinner at a cabin located in the Santa Rosa Plateau Ecological Reserve half a kilometre (a quarter of a mile) away when the radio transmitter went off. When they checked the cage thirty minutes later they found a healthy, twenty-six-kilogram (fifty-seven-pound) male lion about a year old. While they waited for the tranquilizer dart to take effect, Eric York checked the videotape from the motion-sensor camera they’d set up outside the cage.

It showed the lion approach and enter the trap, then pace back and forth and peer between the wires. “Suddenly, another set of eyes glowed in the darkness, and a second puma emerged,” said Boyce. “This puma clawed and dug at the back of the cage and we wondered, was he trying to get the trapped puma out, or did he want the deer?”

The lion circled the trap and jumped onto a large overhanging oak limb. Then a third, much larger lion appeared. As the team realized that there were at least three mountain lions, most likely a mother and cubs, in the area and only one was in the trap, they became more attuned to the darkness around them. Before moving the drugged lion closer to the cabin to examine him, they reset the trap. Forty-five minutes later the door clanged shut. The second young lion was in the trap. They repeated their health check, attached a radio collar and called it a night. Two evenings later, using another frozen deer, they caught the six-year-old mother mountain lion at the same location. And six months later they recaptured all three lions within a few days employing the same method.

“We now know this behaviour is not unusual,” said Boyce. “Pumas are predators and scavengers. Hunting and killing your dinner is hard work. And there is always the risk of being injured by your prey. A puma whose nose leads it to a dead deer finds an easy meal. The difficult part of capturing cougars this way is obtaining bait, it’s labour intensive. We work closely with agencies that monitor road networks. When we get a call about a deer carcass on the road someone goes out to pick it up.”

Finding dead deer to use as bait is one thing, but discovering wildlife where you don’t expect it is another. Some terrestrial mammals in North America are amazing scientists with their long walkabouts. In 2008, DNA from fur and feces revealed that a wolverine in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of northeast California had travelled approximately a thousand kilometres (six hundred miles) from the Sawtooth Mountains in Idaho. A radio-collared fisher, also from Idaho, surprised researchers by regularly meandering sixty-nine kilometres (forty-three miles), a remarkable feat for such a small animal. Gray wolves are also wandering back to Wisconsin, and coyotes are creeping eastward.

Winston Vickers of the UC Davis Wildlife Heath Center prepares to dart a mountain lion as another team member distracts it. Unlike most researchers, the UC Davis team doesn’t use hounds to tree their subjects. Instead they bait traps to capture lions. And since the big cats are most active during the darker hours, the field crew often works the night shift. Photo by Pablo Bryant, courtesy UC Davis Wildlife Health Centre

Cougars are getting into the act too. When they’re about eighteen months to two years old their mother lets them know it’s time to be independent. Besides honing their hunting skills, they also have to find and claim their own home turf. According to Cougar: Ecology and Conservation, edited by Maurice Hornocker and Sharon Negri, a male cougar’s territory may range from 120 to 1,125 square kilometres (75 to 700 square miles) depending on habitat and prey. A female’s will typically be around 40 to 80 square kilometres (25 to 50 square miles). Male ranges overlap with female ranges and sometimes those of other males, although the males tend to avoid each other.

Dispersing is necessary to control cougar populations and to prevent inbreeding. But the search for home ground is a perilous journey. Young cougars are at increased risk of death due to starvation, close contact with humans or being hit by vehicles. It’s especially dangerous for young males who are chased out of other males’ territories and are sometimes—perhaps often—killed in the process. Female cougars seem more tolerant when it comes to sharing their territory. Many adolescent females establish ranges within a five-minute walk of mom’s, and may even overlap it.

Cougars require habitat that provides enough cover for stalking, along with adequate prey. And, as well as needing to find a spot that’s not occupied by a dominant tom, young males need mates. In a 2010 South Dakota State University paper titled “Dispersal Movements of Subadult Cougars from the Black Hills,” Daniel J. Thompson and Jonathon A. Jenks noted that even if a territory is vacant and adequate prey is present, a male cougar tends to continue travelling until he finds those conditions plus one or more available females.

It’s normal for a young male to disperse 160 to 480 kilometres (100 to 300 miles), but apparently some are prepared to walk even farther in their search for sex. In 2004 scientists were astonished when a young adult male cougar weighing 52 kilograms (114 pounds) was killed by a train near Red Rock, Oklahoma. Its radio collar identified it as part of a South Dakota University research project in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Experts figure that in the eleven months since the cougar was tagged, it travelled at least 1,600 kilometres (1,000 miles). Four years later, DNA from a young adult cougar shot in Chicago (the first recorded in the city since 1855) suggested he also hailed from the Black Hills and had covered around the same distance.

But who would expect to find a wild cougar a ninety-minute drive from New York City? Especially when the last documented sighting in the state was in the late 1800s. Apparently Paul Beier, a cougar researcher, professor at Northern Arizona University and president of the Society for Conservation Biology, did. When asked how far he thought migrating cougars might go, he speculated they would reach New Jersey. And when an SUV hit a young adult male outside Milford, Connecticut, in June 2011, he was proved right. The healthy 64-kilogram (140-pound) cat was collared in the Black Hills in 2009. By the time he met his death two years later, it’s estimated he walked 2,415 to 2,900 kilometres (1,500 to 1,800 miles)—the longest recorded journey of any North American land mammal to date. In an ironic twist of fate, the cougar was run over just three months after the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared the eastern cougar extinct.

But what’s more significant is that male mountain lions aren’t the only ones travelling long distances. Since 1996, Utah State University has been studying lions in the Monroe and Oquirrh mountain ranges. Now in its seventeenth year, it’s one of the longest continuously comparative lion studies in the world. In February 2005, researchers fitted a young female cougar in the Oquirrh Mountains with a GPS radio collar. She was only 354 kilometres (220 miles) away when a hunter shot her in Meeker, Colorado, a year later. But her GPS unit revealed she’d travelled more than 1,340 kilometres (833 miles), crossing an interstate highway and three major rivers, as well as climbing a 3,350-metre (11,000-foot) mountain along the way. Three years later, a young female cougar killed in Saskatoon was found wearing a collar from the Black Hills study. It’s estimated she’d travelled more than 1,100 kilometres (684 miles). And in March 2013, a mature female cougar, also from the Black Hills, was killed 676 kilometres (420 miles) away in Montana.

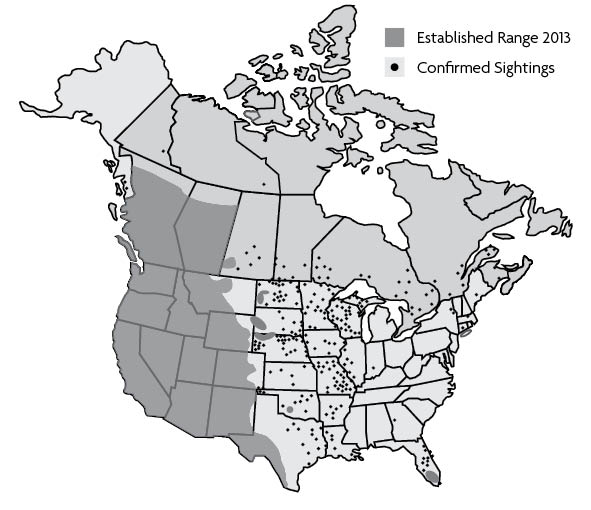

Dots indicate confirmed sightings as cougars migrate out of established range. Information from the Cougar Network, Government of Canada agencies and François-Joseph Lapointe of the Université de Montréal

What’s particularly interesting about these incredible journeys is that five out of the six cats originated in the Black Hills, where mountain lions became locally extinct in the early 1900s. Over time, they recolonized the area on their own and estimates of the population in 2010 ranged from 150 to 300 animals. Although the majority of cougars dispersing long distances have been young adult males, the fact that some females are doing so—plus increased documented sightings in the Midwest and southern and eastern Canada and the US—indicates the possibility of additional colonies being established.

Who knows? Perhaps cougars will eventually reclaim their former habitat and roam North America from coast to coast. But will people residing in areas that haven’t had cougar populations for more than a century be prepared to accept the predator?