The mountain lion works a strong magic in the imagination of many . . . It is the ultimate loner, a renegade presence in the wildest canyons and wildest mountains, the sign of everything that is remote from us,

everything we have not spoiled.

—Donald Schueler, Incident at Eagle Ranch

The bed jiggled and a cold nose nudged my hand. Bailey needed a bathroom break. Our thirty-six-kilogram (eighty-pound) golden retriever–shepherd mix rarely goes out in the middle of the night. But he wanted out right then and, since Rick was away, I had to get up. The fir boards of the floor felt cool beneath my bare feet as I shuffled through the dark kitchen. I opened the door and was reaching for the screen when I heard the scream. A woman’s being murdered in the green space behind my yard! I thought in horror.

I yanked Bailey back, slammed the door and leaned against it as if holding all the demons of hell at bay. Call 911! was my second thought. I heard the scream again and bolted for the bed, leapt in and pulled the covers over my head. I knew then that it was some kind of animal out there, not a woman. But the only being that came to mind was Tsonqua, the Wild Woman of the Woods in west coast First Nations lore. Lowering the covers slightly I peered at the French doors leading onto the deck and considered moving to an upstairs bedroom.

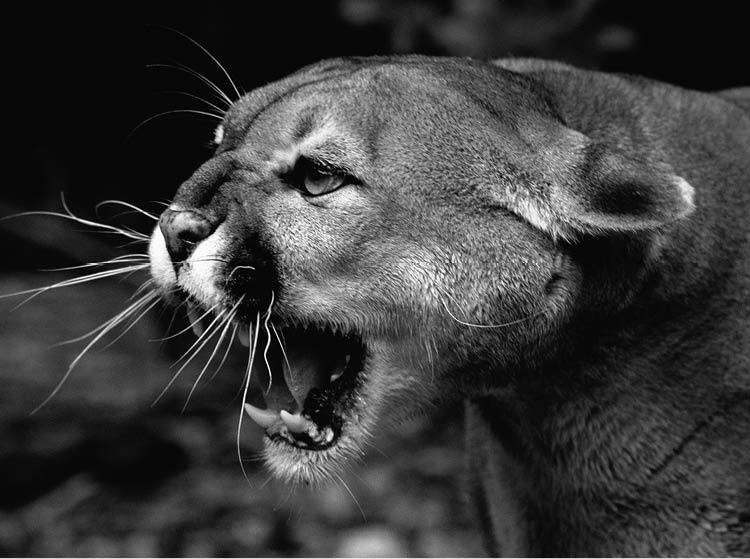

The next morning I googled animal screams and listened to coyotes, rabbits, owls and other creatures make unpleasant sounds until I found what I was looking for. A cougar had visited the green space the previous night. Although the big cats are extremely quiet, they do hiss, purr, growl and make bird-like chirps. And sometimes they scream. Lyn Hancock, author of Love Affair with a Cougar, has heard captive cougars scream when they were sick, desperate or females in heat. Judging by the internet sound bites, it was the latter I’d heard. I saw that the noise has been described as “a nerve-wracking, demoniac and terror-striking caterwaul.” That summed it up well.

I heard the cougar scream years before I began this book. But it’s something a person never forgets. I didn’t know that experience would eventually take me on a journey that would include mock encounters with cougars in the backcountry of BC, as well as years of research and then more of writing.

Cougars are extremely quiet but they do growl, purr and hiss, as well as make bird-like chirps and occasionally shriek like a banshee.

I made one mistake while researching this book and it was a big one. I read every cougar attack description I could find over the course of two days. For the next week I flinched whenever Bailey entered the room and disturbing dreams interrupted my sleep. I wondered if I’d ever be able to walk in the woods again. Then one day I did. Yes, I was very aware of my surroundings. And yes, a cougar could have been lurking in the thick undergrowth along the side of the trails. I knew they passed through the neighbourhood searching for prey—and apparently boyfriends too. But not long into the walk I realized I didn’t feel frightened, I felt confident. Because I knew what to do if I ran into one of the big cats.

People are fascinated by cougars. They’re wild and beautiful, shy and secretive, curious and mysterious. They are compelling icons of everything humans fear and admire. And sometimes they’re deadly. Seeing a cougar is rare and being attacked by one even more so. But, as civilization continues to encroach on cougar habitat, the number of people living in and exploring rural and wilderness areas increases, and if cougar populations and territories continue to expand more interactions are inevitable. There will always be some level of risk. However, it can be reduced.

When asked if he thought humans and mountain lions could coexist, Winston Vickers of the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center replied, “It’s clear that we do. The data shows that, in some places, we’re coexisting at relatively close quarters without conflict. That happens fairly regularly around urban and exurban development. Given the low number of attacks and proximity of humans and lions, people aren’t aware of just how much coexisting is going on.”

We live on a small acreage on the outskirts of Courtenay on central Vancouver Island. One evening late in the summer of 2012, I was getting laundry off the clothesline, located thirty-three metres (thirty-six yards) from the house. Suddenly Bailey’s hackles stood straight up and he crouched low to the ground, a steady growl rumbling from deep within his chest. The wild part of our property was about fourteen metres (fifteen yards) from where I stood. I scanned the tangle of trees, bushes and undergrowth but couldn’t see anything.

A variety of wildlife crosses through the back of our property, and sometimes the occasional person. Whether it’s a feral cat, deer, bear, bunny or someone who’s strayed off the trail below, Bailey always runs to the post-and-wire fence and barks until we tell him it’s okay. He’d done that for ten years. But now he was very slowly backing up toward the house. I hesitated for a few seconds then balanced the laundry basket between an arm and a hip, waved the other arm in the air and spoke firmly and loudly as I joined Bailey in a slow retreat to the back door.

Was it a cougar? Who knows? The following day when I met the next-door neighbour on the street, he asked if I’d seen any sign of bears lately. When I said no and asked why, he said he’d gone outside the night before and gotten a creepy feeling he’d never experienced in his more than two decades of living here. Just as I’d followed Bailey’s cue, he’d paid heed to his intuition and gone back inside. Since that incident Rick has cleared the brush on the wild side of the fence to provide a better sightline from the house and yard and to make it less likely something big could sneak up on us.

Working on this book generated a wide range of emotions. I was appalled to discover how humans had heedlessly killed cougars in the past and horrified by accounts of cougars attacking humans. Research on the cat’s behaviour piqued my curiosity and I cried when I read about Max, the cougar confined to a barn stall for ten years. But most of all I felt awe at the power and grace of the cougar: the sleek and supple perfection of its body gliding through the landscape and leaping from precipices in absolute silence. At times the symmetrical beauty of the cat’s facial markings moved me in an inexplicable way. And always I admired the carnivore’s intense focus.

Like most cats, cougars are curious and drawn to moving objects. Evidence indicates they watch and observe humans more frequently than most people realize. Photo by Brad Boner, courtesy Panthera

Over the centuries cougars have been revered, feared, persecuted and protected. As the dynamics of cougar–human relationships continue to evolve, I wonder about the future. How will people perceive cougars ten or one hundred years from now? And what impact will that have on cougars, people and the environment? In the meantime, I imagine cougars moving through shadowy forests and resting on sun-warmed rocks, living their mysterious lives mostly beyond human view. But watching us. And surviving.