One of the most legendary and least understood mammals of North America.

—DR. CATHY SHROPSHIRE, wildlife biologist,

Wildlife Mississippi Magazine

Heavily falling snow covered our footsteps almost as quickly as we made them. The fat white flakes, the forest around us and the arrival of twilight meant visibility was fading fast. And right in front of us, filling with snow as we watched, were the large paw prints of a cougar.

Our pickup was parked a couple of kilometres (about a mile) from the small logging and pulp mill community of Port Alice on northern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. We’d pulled off Highway 30 onto the SE Main, a logging road at the bottom of the hill heading out of town, to retrieve our thermos from the back of the truck. But now, following the tracks into the woods toward a small creek, our thoughts were on cougars. As the snow silently erased the paw prints I peered between the alders and up into their branches with equal measures of apprehension and excitement.

Elusive, graceful, powerful. Whether they’ve seen one in the wild or not, most people are fascinated by the big cat called cougar, puma, mountain lion and approximately forty other names. And the animal’s size is part of the allure. Although it’s not the norm, there are records of cougars measuring close to three metres (slightly over nine feet) long from the tip of the nose to the end of the tail. It’s said that in 1936, John Huelsdonk, known as the Iron Man of the Hoh River on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, shot a cougar that stretched out to 3.35 metres (11 feet). Possibly the heaviest cougar on record was killed by an Arizona government worker in 1923. It weighed more than 125 kilograms (276 pounds). And that was after the intestines had been removed.

But don’t let their size mislead you about the cat’s speed and agility. Exceptionally long legs make cougars Olympic-class athletes when it comes to jumping. They’ve been observed leaping 5.5 metres (18 feet) straight up from a standstill, 18.5 metres (60 feet) down from a tree and nearly 14 metres (45 feet) horizontally onto the back of a deer. Noted conservationist, author and former cougar hunter Roderick Haig-Brown wrote that the big cat’s “muscles are powerful enough to swing his weight completely around in mid-air.” Cougars can run up to 72 kilometres (45 miles) per hour for a short distance, and even a smaller 45-kilogram (100-pound) cougar is capable of taking down a 318-kilogram (700-pound) elk.

Cougars are the fourth-largest cat on the planet and the biggest in Canada. The only feline of greater size in the Americas is the jaguar, which is primarily found south of the United States. Cougars were one of the most widely distributed large mammals in North and South America, but their populations were severely impacted by bounty hunting in the early to mid-twentieth century. In 2011 the United States declared the eastern cougar extinct and, aside from a small group of endangered Florida panthers, no one knows if any of the big cats are breeding east of the Mississippi River. But cougar numbers are stable and even increasing in many areas of western Canada and the United States, and some are even making their way to the Midwest and beyond.

At different times throughout the centuries humans have viewed cougars as mythical icons or mortal enemies, and called the big cats abject cowards or bloodthirsty killers. And cougars have the distinction of being classed as both predator and prey. During the bounty years, hunters were paid to shoot them; now most jurisdictions require people to pay for the privilege of doing so. Today, cougars are seen as symbols of agility, sex and power, and are frequently used as mascots for sports teams and in advertising campaigns. “Cougar” has also become the popular slang term used to describe mature women who prefer romantic liaisons with men a decade or more younger than themselves.

Although cougars normally claim the wild backcountry as home, it’s not unusual for a big cat to casually stroll through a suburban subdivision under cover of darkness. Or to occasionally appear in such unlikely urban locations as the parking garage of the Fairmont Empress Hotel in British Columbia’s capital city of Victoria. So, how does a cougar mysteriously materialize in a busy downtown area without being captured or shot somewhere along the way?

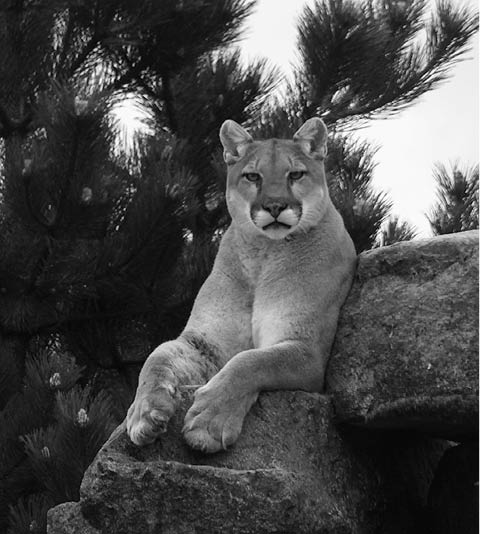

A cougar’s muscular front legs make it the Popeye of the animal kingdom. These legs, combined with oversized paws and razor sharp claws, make the big cat a formidable hunter capable of taking down prey as large as a full grown elk. Photo courtesy Cougar Mountain Zoo

Part of the reason is their large padded paws, which allow the cats to travel in near silence. And they’re masters at blending in, which is one reason they’re sometimes called ghost cats. Even people who work in cougar country rarely see them in the wild. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t there. Odds are that one has watched you walk through the woods while you’ve been totally oblivious to its presence. And that’s part of what makes the cougar an icon of all that is beautiful, wild and dangerous.

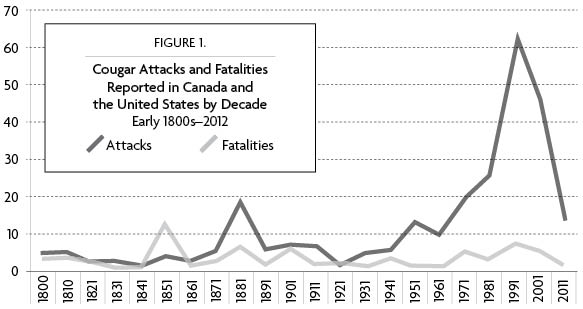

Although cougar attacks are extremely rare, they have increased significantly since the 1970s. Knowing the appropriate way to respond to a cougar can decrease the odds of an encounter becoming an attack and an attack resulting in a fatality. Graph prepared by David G. Eyer

In the last two hundred years there have been 252 documented attack incidents in Canada and the US, involving 255 cougars and 281 people. And statistics show that attacks on humans have increased significantly in recent years. In “Factors Governing Risk of Cougar Attacks on Humans,” an article in the spring 2011 issue of Human-Wildlife Interactions, published by the Jack Berryman Institute of Utah State University, wildlife researchers David Mattson, Kenneth Logan and Linda Sweanor noted the number of “confirmed attacks resulting in human death and fatalities increased four to fivefold between the 1970s and 1990s.”

In the overall scheme of things, however, cougar attacks are extremely rare. A person is far more likely to be killed in a car accident, by a domestic dog or even by a bee sting. Of course, the odds of seeing a big cat or having an encounter with one is higher for people who live, work or recreate in cougar territory. And as urban sprawl continues and more people venture into wilderness areas, encounters are becoming more common.

Most people don’t think about cougars unless one is seen in the neighbourhood or an attack makes the news. After such incidents, while walking the dog in the woods or even relaxing in my rural backyard, I’ve wondered, “Could it happen here?” More frequently than I’m comfortable with, the answer is “Yes.” I’ve also asked myself, “Was the attacked person doing anything I don’t normally do?” The answer is often “No.”

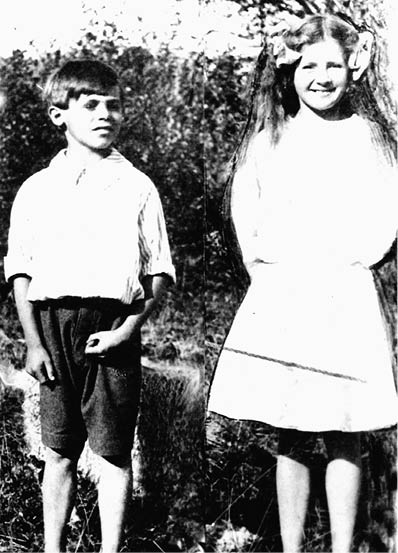

At times I’ve reassured myself by recalling an article I once read about a September 1916 attack near Cowichan Lake in the interior of southern Vancouver Island. One afternoon around 2:00 p.m., eleven-year-old Doreen Ashburnham and eight-year-old Tony Farrer were walking along a trail looking for a pony. They were less than a kilometre (about half a mile) from home when they spotted a cougar crouched on the path ahead. The children turned and ran. Ashburnham later told a reporter, “The cougar sprang from about 35 feet and landed on my back, throwing me forward onto my face. He chewed on my shoulder and bit chunks off my butt. Tony attacked him with the bridle he was carrying. They fought for 200 yards down the trail. The cougar scratched the skin off Tony’s back turning his shoulders, hips and legs into ribbons of flesh and ripped the flesh off his scalp until it was hanging off the back of his head by six hairs.”

Long and exceptionally strong rear legs mean cougars are capable of leaping phenomenal distances: 5.5 metres (18 feet) straight up from a standstill, 18.5 metres (60 feet) down from a tree and nearly 14 metres (45 feet) horizontally onto the back of a deer.

Despite Ashburnham’s injuries and Farrer yelling for her to save herself, the girl raced to her friend. “I jumped on the cougar’s back and started hitting it on the head. I reached around and put my arm in his mouth so he’d stop biting Tony—you can see where I got nicely chewed up in a few thousand places—and I managed to scratch his eyes a little bit and it finally let go.” Covered with blood, the children staggered home. “I remember my father taking Tony’s clothes off and throwing them on the bathroom floor,” Ashburnham said. “To this day I can see blood running out of the bathroom.”

Although they survived, both children were badly injured. Farrer required 175 stitches to his head alone and was hospitalized for a lengthy period. Ashburnham’s right arm was badly mauled and she developed blood poisoning. A few days after the incident, an underweight two-and-a-half-year-old cougar with cataracts was found in the area and shot. In 1917, on behalf of the king of England, the Governor General of Canada presented the Albert Medal to Ashburnham—the youngest female recipient at the time—and Tony—the youngest recipient ever—for “gallantry in saving life on land.”

Although eight-year-old Tony Farrer and eleven-year-old Doreen Ashburnham were severely injured, they fought off the cougar that attacked them. They were successful because they stuck together and focused their blows on the cougar’s face and eyes. In 1917 they were awarded the Albert Medal for “gallantry in saving life on land.” Photo courtesy Kaatza Station Museum and Archives P985.4.1

The bravery of these two youngsters was impressive, and I thought if they could fend off a cougar, perhaps I could too. But the incident raised some questions. It’s likely the cougar that attacked Ashburnham and Farrer did so because cataracts made it difficult for it to see and hunt. Out of 255 cougars involved in attack incidents over the past two hundred years, the condition of 168 is unknown. As for the others, 40 were classed as skinny or starving, 6 were injured or sick and 41 were healthy. And fifty-three percent of the victims were adults. So it isn’t just sick, starving or injured cougars attacking children. Sometimes healthy, mature cougars—even ones that have recently eaten—stalk and attack adult humans. I wondered if it was simply a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Or was something else going on? And what about the stories of particularly aggressive cougars on Vancouver Island and in southern California?

My great-grandfather, Frank Hicks, was buddies with Theodore Roosevelt, one of the most famous big game cougar hunters in North America, and I saw my first live cougar in Washington state before I could walk. Since then, I’ve found fresh tracks on northern Vancouver Island, seen what a guide referred to as “mountain lion poo-poo” in Mexico and heard a cougar scream in the green space behind my home. But until I began research for this book, I knew little about the big cats. I wasn’t sure what to do if I saw a cougar, and didn’t know the best way to prevent or survive an attack.

But my interest wasn’t solely driven by fear. I also knew the cougar was a remarkable animal and that as a large predator, it played a significant role in nature. I wondered if cougar populations would continue to rebound or if, as some say, they’re in danger. What would happen if cougars disappeared? As I studied the situation it became apparent that cougar populations and people’s perceptions of the big cats are intimately connected, and that this relationship has the potential to profoundly affect the environment.