Audrey set aside her clothing and mounted a small stand in the center of the studio. A workman proceeded to paint her entire naked body with a mixture of oil and grease. This was the first step for her to be cast head to toe in plaster for a sculpture. Audrey just hated it, but she brazened it out, as she always had done.

Guided by the sculptor, Audrey assumed the desired pose. The casting began. Workmen mixed up small batches of plaster of paris until it was sticky and soft. Two casters then began wrapping the warm plaster around Audrey’s feet. They applied layer after layer, patting the plaster firmly onto her flesh until she was rooted in a solidifying mass eight or ten inches thick.

The workmen had to work fast because the plaster dried quickly. Handful by handful, they worked their way up Audrey’s body—up her legs, around her hips, over her torso and her breasts and her shoulders—until she was entombed up to her throat. Swaddled in the huge, sloppy mess, she felt like a large snowman beginning to melt.

The most unpleasant part came when the casters had to enclose Audrey’s face and head. They stuffed her ears with cotton and slipped a silver tube between her lips for her to breathe. She closed her eyes so that an extra coat of oil and grease could be painted onto their delicate lids. Although she knew what was coming, there was no way to be prepared. It was like a living death. The casters began smearing soft lumps of plaster onto her face and the back of her head. The final touch was for a workman to stand on the table beside her and pour the remaining plaster from the bucket over her head.

“Inside, the girl cannot move so much as a fraction of an inch. She is virtually part of the plaster itself. It is nothing less than a horrible sensation,” Audrey later complained.

“I have tried to draw a full breath through my silver tube, only to find that I could not—there was no room inside of me for more than just the amount of air I had been breathing while the plaster was being put on. And once I was almost strangled because the workmen slapped the plaster onto my stomach and chest while I was exhaling a breath, and it hardened into place a moment later while I was again exhaling, giving me no room for expansion with the next intake of air. I had to breath[e] in little jerks till the mold was complete. Imprisoned in this way the model feels as if all the heaviness of the universe were pressed about her, slowly crushing her to death.”

For the model, it was an excruciating process. For the voyeuristic public, on the other hand, the spectacle of a naked woman being slapped with wet plaster might prove rather more erotic.

The casting of Audrey in plaster was to be the centerpiece of her first movie, Inspiration. For this key scene, Audrey had to be entirely naked. It was a breakthrough in cinema history.

France, naturellement, had pioneered nudity in film. George Méliès’s After the Ball, a one-minute scene of a servant bathing a woman, starring the director’s future wife, is generally credited with featuring the first nude on camera. Already by 1907, there were underground pornographic films circulating in America. The first mainstream American film featuring nudity was probably Hypocrites, which opened at the Longacre Theatre in New York on January 20, 1915. The film was written, directed, and produced by Lois Weber, the first American woman to become a major movie director. In the film, the hypocrisy of a church congregation is exposed by the nude figure of the uncredited Margaret Edwards as the allegorical character Truth. She was metaphorically and literally “the naked Truth.”

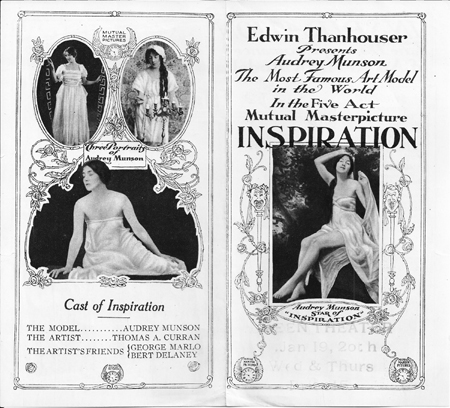

Inspiration, released ten months later on November 18, 1915, made Audrey the first leading lady in America to appear nude in a film. She became America’s first naked movie star.

The film industry at the time was split between the upstart independents and the would-be monopoly known as the Trust, organized by inventor Thomas Alva Edison, who falsely claimed to have invented the motion-picture camera and projector and controlled most of its patents. Motion-picture producers required licenses to make movies using the Trust’s patented equipment. But feisty independents, largely Jews and Catholics, mounted a determined challenge, producing films that were both long and more zesty than the complacent product of the overwhelmingly WASP Trust. Several of these swashbuckling pioneers would go on to become the megaliths of today: Universal, Fox, and Paramount.

Inspiration was made by the Thanhouser Company, one of the independents. In all, it produced over 1,000 movies—though it never made the journey west like other independent producers to California, where Hollywood was born.

Edwin Thanhouser was the first American movie producer to come from a background in the theater. A former actor, like his wife, he had run his own stock companies before making a success of the Academy of Music in Milwaukee. He set up in the movie business in 1909, renting an old wooden skating rink in the New York suburb of New Rochelle. The town was a popular refuge for Broadway’s theater people. Stars like Audrey could easily commute from Manhattan. Tin Pan Alley songwriter George M. Cohan, who grew up in Providence like Audrey, named a musical after the train ride from New York to New Rochelle: Forty-Five Minutes from Broadway.

Because of his thespian past, Thanhouser earned a reputation for luring fellow actors into the movie business. Hiring Audrey, however, was the first time he had pounced on a model from the art world. “Not content with causing stage celebrities to migrate ‘45 minutes from Broadway,’ he has now saddened the hearts of the Washington Square soft collar and flowing tie contingent by snatching from their midst ‘Divine Audrey,’ and he promises that in Inspiration, which is the title of her first release, he will give the pro- and con-ers of motion pictures something to talk about,” Moving Picture World reported.

Inspiration opened new horizons for Audrey. She could now set aside her hopes of a stage career for a dream of the silver screen. Propelled by the power of movie advertising in local papers across America, Audrey suddenly became a household name.

Despite her clash with Albee, Audrey got a crucial helping hand from the man who had been penciled in to direct her “beauty act” on tour. Arthur Hopkins was just breaking into directing himself. One of nine children of a Welsh miner who died when he was young, Hopkins had started out as a newspaperman. As a young reporter for the Cleveland Penny Press, he got the scoop on the man who shot President McKinley at the Buffalo World’s Fair. He rushed by horse-and-buggy to the Cleveland suburb of Newburgh, where the local priest told him that the assassin, Leon Czolgosz, was an anarchist.

Hopkins first got into show business as the press agent for Cleveland’s new Colonial Theater, which he made so popular that the best seats were sold by auction. He moved on to New York to book acts ranging from bears to brass bands for the booming new amusement parks. Hopkins graduated to Broadway, where he worked first as a talent agent and director before producing his first big hit, Poor Little Rich Girl at the Hudson Theatre in 1913. At the time of The Fashion Show, he had a two-room office in the Putnam Building with the United Booking Office. He went on to become a playwright, director, and producer of some eighty plays, including John Barrymore’s famous Hamlet. When Audrey was unceremoniously dumped by Albee, Hopkins stepped in and acted as her manager in negotiating her first movie deal with Thanhouser.

Loosely based on Audrey’s own life story, Inspiration retells the timeless tale of the young girl who seeks her fortune in New York. In the press agency’s account, Audrey is not discovered by the middle-aged Herzog but by a group of young Greenwich Village gallants out for a drive.

“Like thousands of the girls, Miss Munson came to New York alone pursuing elusive opportunity. New York was not kind to her and her little pile of savings grew lower and lower. But just as in popular fiction the silver lining of the cloud appeared when the deluge threatened and in the most Bohemian sort of way imaginable the girl was struck by an automobile as she crossed a street near Washington Square, the rendezvous of artists,” the press agent said. “In the machine were several men, one a sculptor in search of a model. When they learned the girl was not hurt and was looking for work the artist asked her to come and pose for him. Of course, he did not recognize what a find he had in this slim, hungry girl whom chance had thrown in his way. But when he came into the studio and saw the beauty and vivacity of the girl, he was amazed. That was the beginning of the brilliant career of Audrey Munson.”

In the film, the Audrey character secretly falls for her sculptor savior as he sculpts his masterpiece, Inspiration. When the work is done, she disappears, leaving him a note, convinced that he has fallen for one of the rich young women who frequent his studio. Of course, the sculptor is secretly in love with her too. Heartsick, he searches the city until he finds her in a miserable heap at the base of the Maine Monument in Columbus Circle, where he has gone to gaze on her features again in the statue.

Moviegoers, not surprisingly, loved the sight of the naked Audrey getting caked in warm, wet plaster. Audrey’s poses plastiques, in the form of her famous statues, also went over big—particularly the scene in which Daniel Chester French’s Evangeline dissolves into her nude body. “When it comes to nude posing ‘Inspiration’ has anything in the line of picture entertainment beaten to a frazzle. ‘Hypocrites’ caused comment with its nude figure flitting here and there in a semi-seeable manner, but in this there is no doubt one is seeing the real thing,” Variety declared. Movie Weekly ran a generally positive review, calling it “undeniably novel” and “a bit daring.” It was followed by a footnote: “The preceding review completely overlooks the raison d ’ être for the film: the nude exhibition of Miss Munson’s anatomy!”

Thanhouser was accused of trying to exploit Audrey’s nudity on-screen. But he defended his artistic purpose. Firing off a letter of complaint to the Morning Telegraph, he insisted: “The impression that I advocate the nude in moving pictures is wrong and should be corrected.”

Inspiration did gangbusters at the box office in Los Angeles, which was just emerging as the moviemaking capital of the world. The movie magazine Reel Life, the house organ of the film’s distributor, did the math: Inspiration played to a full house for nine showings a day through the entire two-week run at the Garrick Theatre, capacity 1,000. That meant 126,000 people saw the film, or almost 40 percent of the city’s 319,198 population. “For a film to create a furore in Los Angeles is unprecedented,” Reel Life concluded.

It was the same success story elsewhere. “There is absolutely no chance of ever taking in more money in this house in one day than we did yesterday, for we played to absolute capacity from opening until closing time, and could not have played to another 50 people—all of which goes to show that a good picture, well advertised, will go over big,” Herman Fichtenberg, owner of a chain of theaters in New Orleans, said.

Back in the film’s hometown of New Rochelle, however, the nude Audrey ran into opposition. Before the opening, a committee of clergymen showed up at the North Avenue Theater and demanded a private screening. Charles Jahn, the theater manager, capitulated and let them in. As a result, the film was canceled. “Many of our residents have seen this picture at Loew’s Circle Theater at 59th Street and can see nothing objectionable,” Jahn complained. A letter from a Frank Egan to the New York World tartly observed: “It is difficult to understand New Rochelle morals when it permits motion pictures to be manufactured within its limits which it will not permit to be shown there because of the pictures being ‘suggestive and likely to be harmful to young men and women.’ ”

The most severe reaction came in nearby Ossining, New York, where some of the wealthiest women in Westchester County had set up a censorship committee for the Civic League. Theater owner Louis Rosenberg was arrested at the league’s behest and charged with corrupting the morals of a two-year-old boy who saw Inspiration on his mother’s knee. The mother, Grace O’Neill, had walked out when the sculptor had wrapped Audrey in plaster only up to her knees. She admitted she did not know if her toddler, John, had been corrupted. The only visible ill effect, she said, was that he chewed off the leg of a red doll. When John was asked about the movie, he said only: “Me want more tandy, Ma-a-a!”

Sculptor Isidore Konti, shown in the film, was asked his reaction to the rumpus. As the man who first schooled Audrey about nudity in art, he stood strongly at her side. “To object to the nude is simply stupid. Nude pictures are found in all the noted art galleries,” Konti said.

Audrey was always similarly dismissive of the puritans who would censor her work. Kittie may have had misgivings, but she had learned from Konti’s lectures and stuck by her daughter. Movies were still new, and it was hard to understand why there should be a distinction between art forms. But Audrey and Kittie learned a bitter lesson about the finances of the nascent movie business. Despite Inspiration’s sensational success, and its historical importance as the first American film with a naked leading lady, Audrey complained she made only $450 from the picture—only a fraction of the box office take.