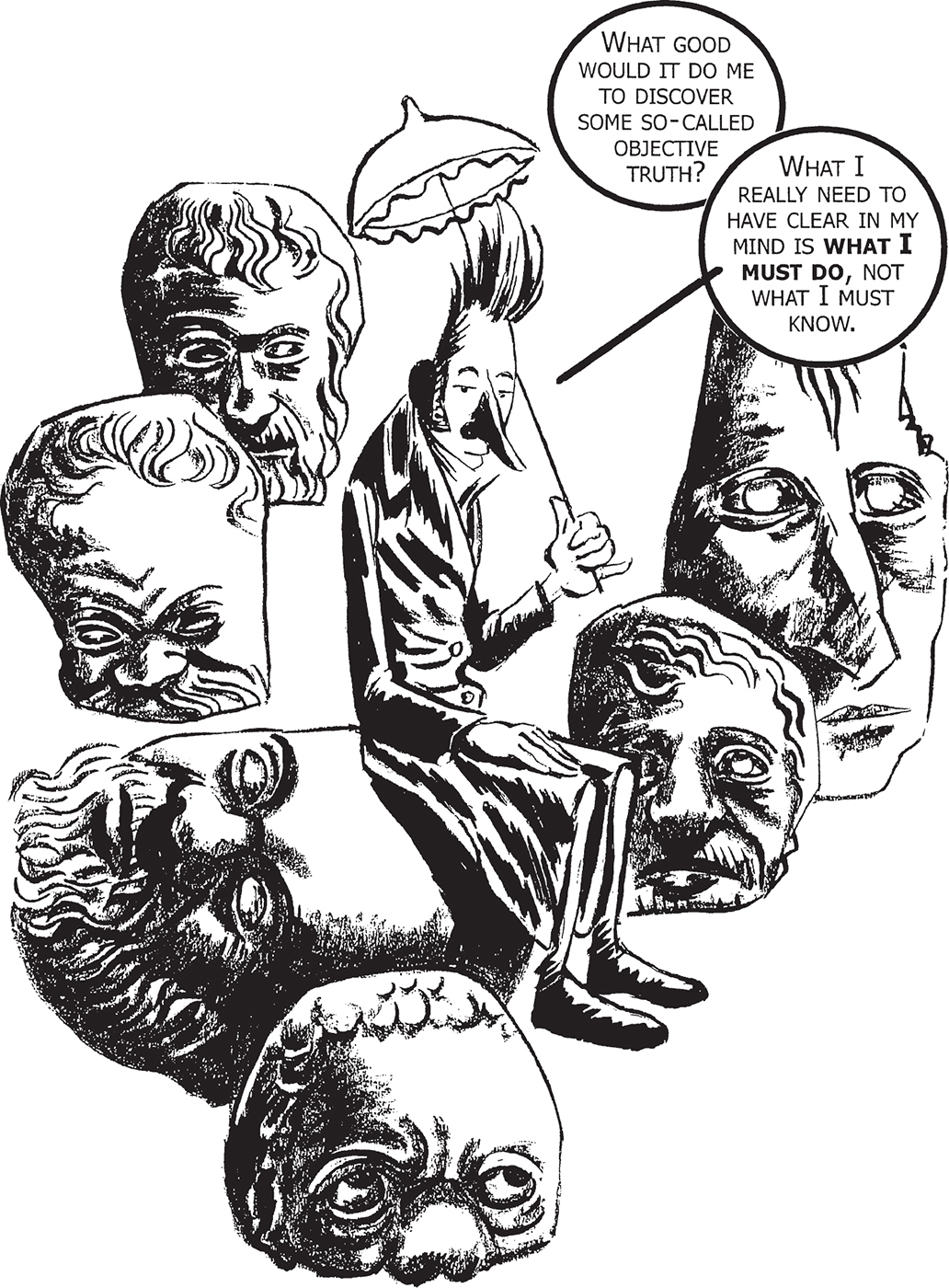

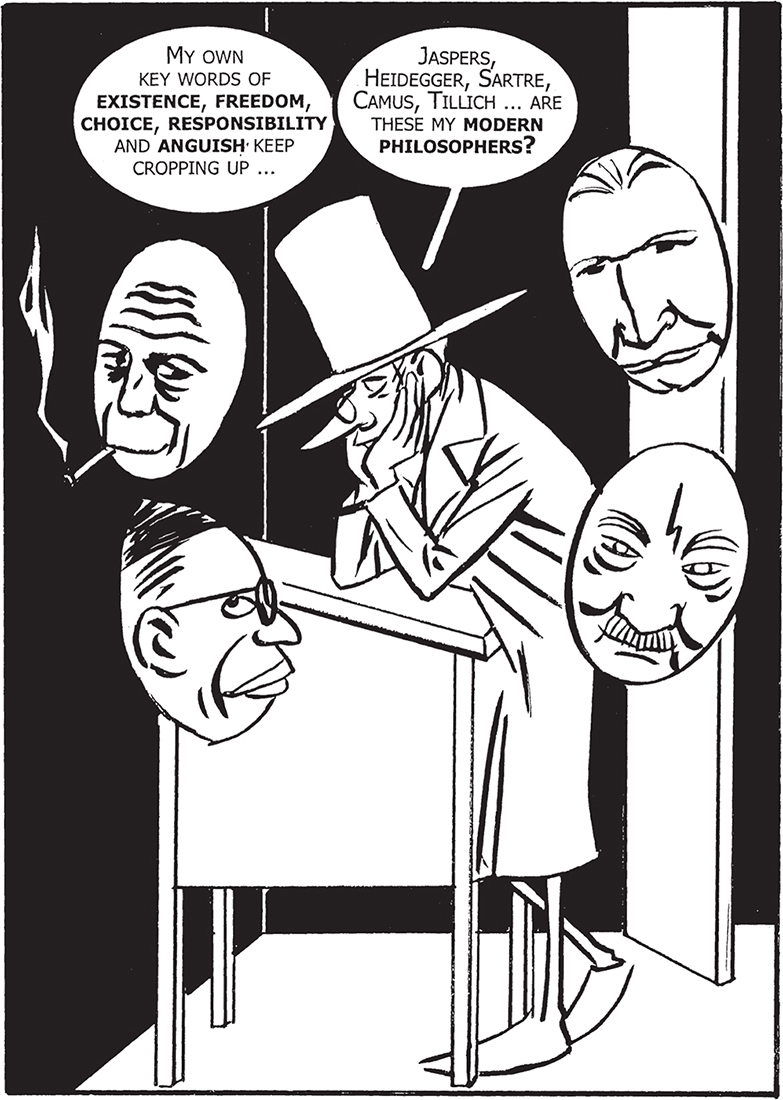

WHAT GOOD WOULD IT DO ME TO DISCOVER SOME SO-CALLED OBJECTIVE TRUTH?

WHAT I REALLY NEED TO HAVE CLEAR IN MY MIND IS WHAT I MUST DO, NOT WHAT I MUST KNOW.

For over 2,000 years, philosophers had insisted that their primary task was to establish what counted as certain and reliable knowledge. Søren Kierkegaard violently disagreed. The job of philosophy wasn’t to tell us what we could know. It had to tell us what we should do.

WHAT GOOD WOULD IT DO ME TO DISCOVER SOME SO-CALLED OBJECTIVE TRUTH?

WHAT I REALLY NEED TO HAVE CLEAR IN MY MIND IS WHAT I MUST DO, NOT WHAT I MUST KNOW.

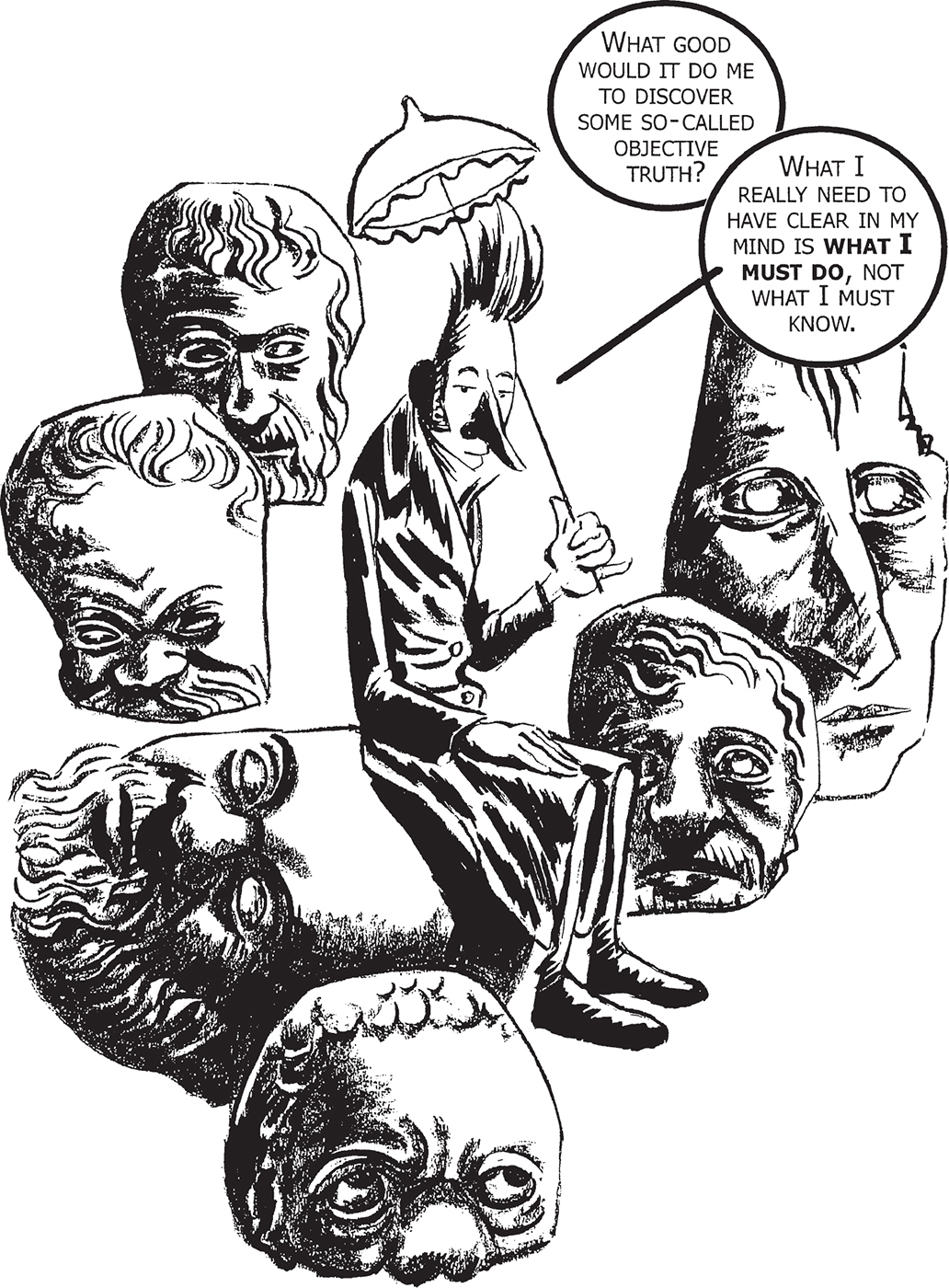

Søren Kierkegaard was born on 5 May 1813, the youngest child of Michael Kierkegaard. His family nickname was “Fork” because, as a child he had once threatened his dinner.

I AM A FORK AND I WILL STICK YOU!

I WAS ALREADY AN OLD MAN WHEN I WAS BORN.

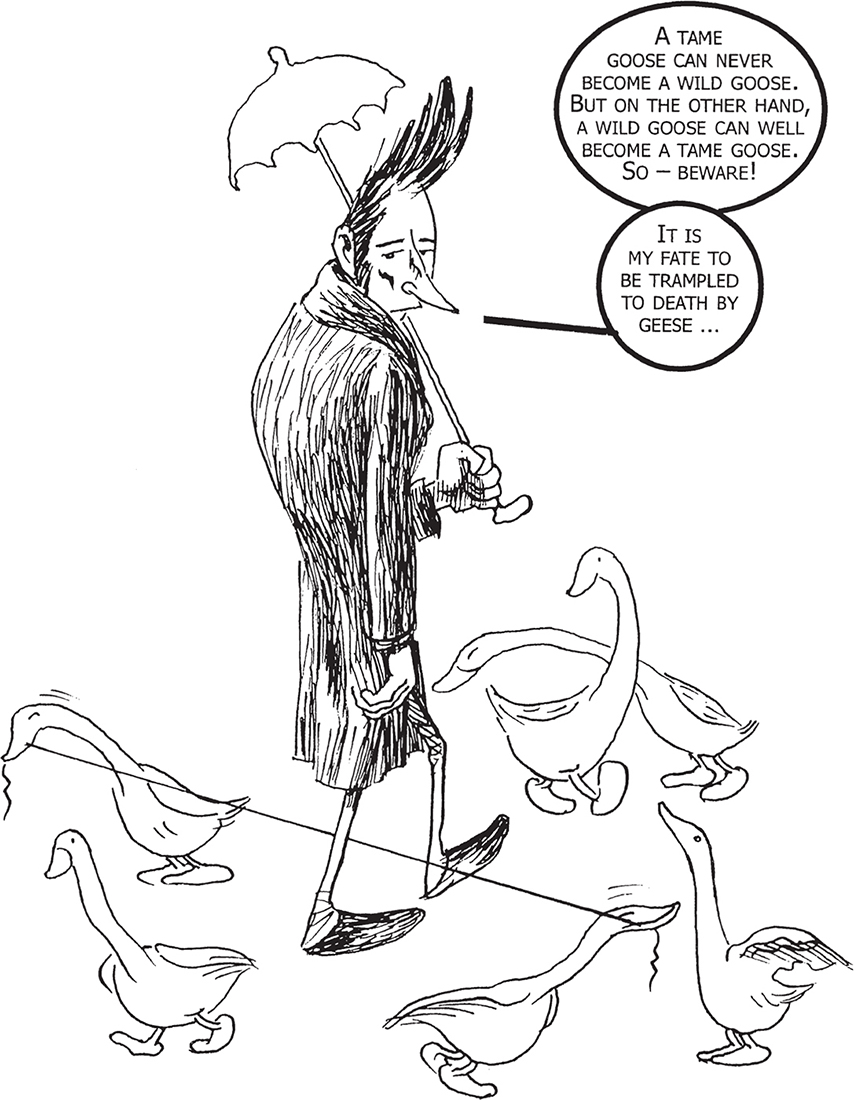

He was a frail child who suffered from a curvature of the spine, probably brought about by an earlier fall from a tree. He also suffered from mysterious fits that left him weak. And for the whole of his life he had an aversion to sunlight. Full-length portraits usually show him sporting an umbrella.

His old father was a remarkable man. He had been born in Jutland, as a landless serf, of an appallingly poor family.

We were called KIERKEGAARD, or “CHURCHYARD” – AFTER A PLOT OF LAND THE FAMILY FARMED THAT BELONGED TO THE LOCAL PRIEST.

He moved to Copenhagen at the age of 24 and rapidly became one of the most successful merchants in Denmark. By the age of 40, he was rich, so he retired from commerce and devoted the rest of his life to reading theology. He was a very intelligent and religious man – a great autodidact who enjoyed discussing Christian doctrine with the various churchmen he invited to his large town house.

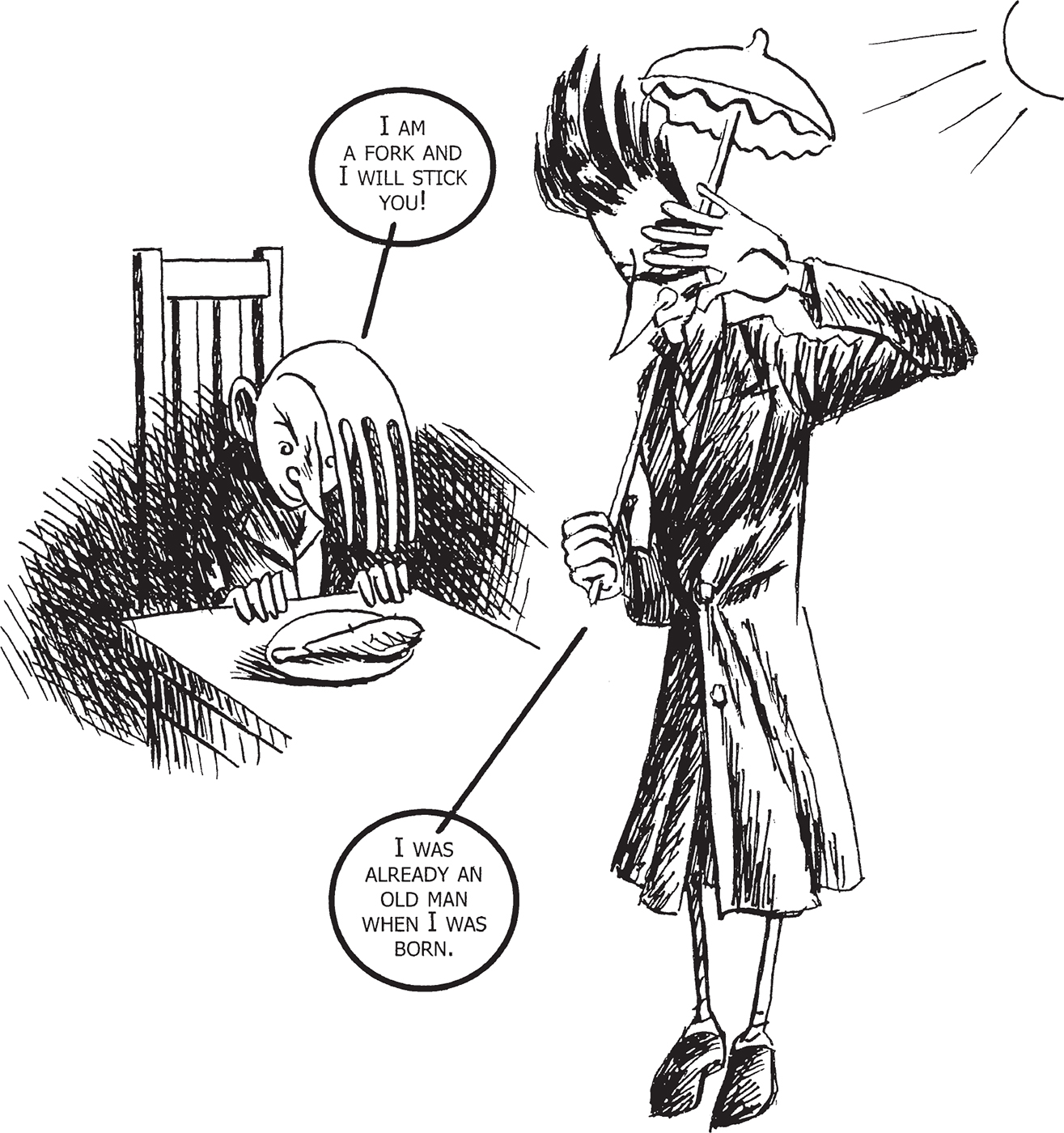

Michael Kierkegaard was also an authoritarian father who demanded correct behaviour and obedience from his seven children and was careful with his money. His religious views were a complicated mixture of orthodox Lutheranism, Moravian piety and an obsessive spiritual melancholy. It was a dark and grim Christianity that stressed the inevitability of sin, punishment and suffering. Søren had to learn a lengthy catechism and recite it to his father every day.

As A CHILD I WAS STRICTLY AND EARNESTLY BROUGHT UP TO CHRISTIANITY – HUMANLY SPEAKING, INSANELY BROUGHT UR

A CHILD TRAVESTIED BY A MELANCHOLY OLD MAN. TERRIBLE!

Søren’s parents were old when he was born. His “heavy minded” father was 56, and his mother Anne, 45. His mother had been the family’s former domestic servant, illiterate, and she seems to have made little impression on any of her children. The father ruled, and was both feared and admired by all his children, especially Søren.

THE RELATIONSHIP WITH MY FATHER, THE PERSON I LOVED MOST, WAS WITH A MAN WHO MADE ONE MISERABLE.

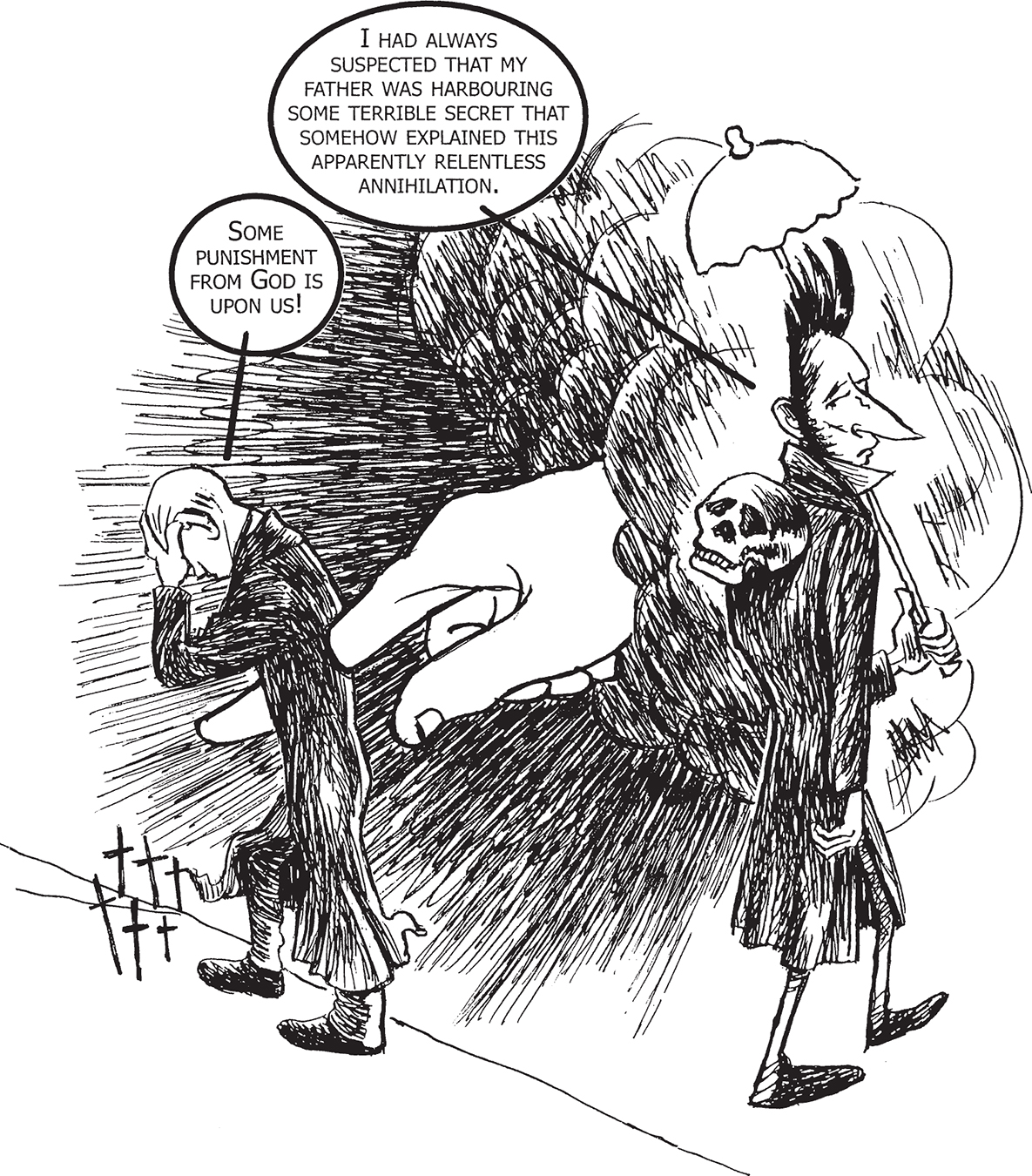

But out of the seven Kierkegaard children, only two survived. The young family and their mother were gradually obliterated by accidents, disease and complications of childbirth. Only Søren and his brother Peter remained. And their father thought he knew why. “The Great Earthquake” happened in 1835 when the old man told the truth at last. Søren was 22.

SOME PUNISHMENT FROM GOD IS UPON US!

I HAD ALWAYS SUSPECTED THAT MY FATHER WAS HARBOURING SOME TERRIBLE SECRET THAT SOMEHOW EXPLAINED THIS APPARENTLY RELENTLESS ANNIHILATION.

God had rewarded Michael Kierkegaard with material prosperity, but was progressively punishing him by finishing off his children, all of whom would die before they reached the age of 34. (Like Christ, crucified at 33.) But why?

WHEN I WAS A SMALL BOY OF 11 YEARS, AS I TENDED SHEEP ON THE JUTLAND HEATH, SUFFERING GREATLY, STARVING AND IN WANT, I STOOD UPON A HILL AND CURSED GOD.

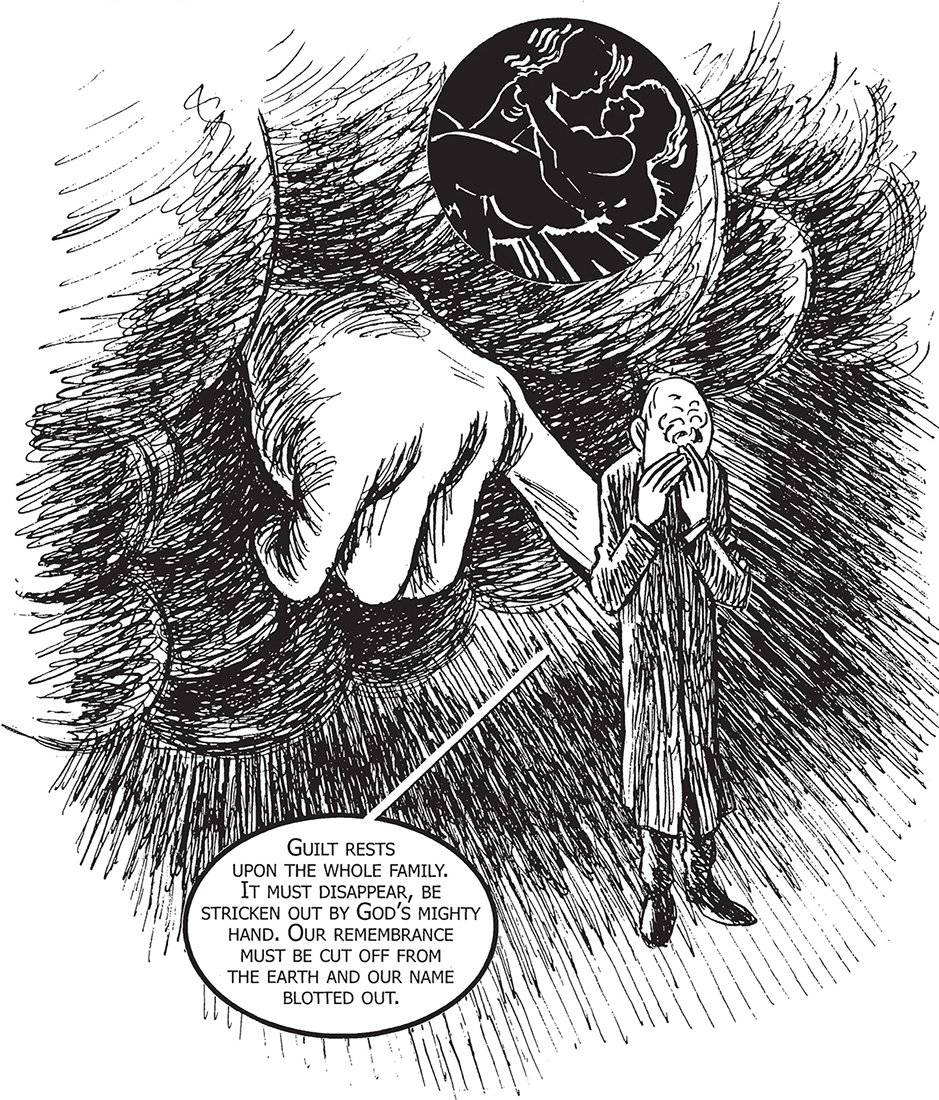

He also confessed to pre-marital sexual relations with his second wife, while she was still a servant, which probably didn’t please God much either. But it was his angry childhood blasphemy that had done for them all.

GUILT RESTS UPON THE WHOLE FAMILY. IT MUST DISAPPEAR, BE STRICKEN OUT BY GOD’S MIGHTY HAND. OUR REMEMBRANCE MUST BE CUT OFF FROM THE EARTH AND OUR NAME BLOTTED OUT.

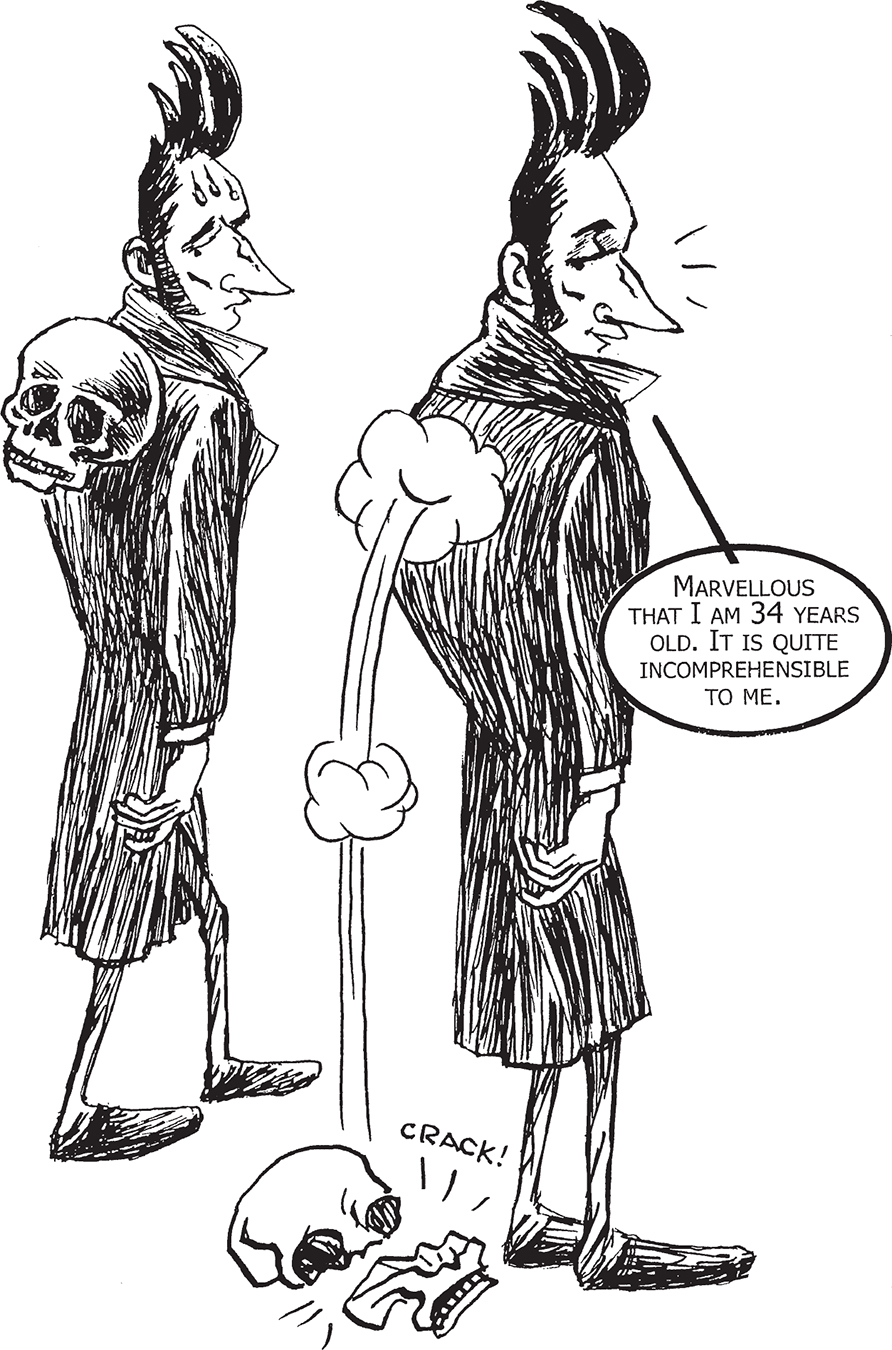

Both boys seemed to have accepted their father’s deranged explanation of the family’s misfortune. They immediately became convinced that they would both die young. So 12 years later, Søren was very pleasantly surprised to find himself still alive.

MARVELLOUS THAT I AM 34 YEARS OLD. IT IS QUITE INCOMPREHENSIBLE TO ME.

Søren became a student at the University of Copenhagen, studying theology and philosophy to become a pastor of the Lutheran church. But, perhaps because of doubts about his longevity, he gave up his studies halfway through. He moved out of his father’s house, lived the life of a scandalous aesthete and devoted himself to a life of pleasure and amusement, which his father (surprisingly) seems to have funded.

I WAS LEADING MY LIFE IN ENTIRELY DIFFERENT CATEGORIES.

He soon discovered the joys of reading literature, as opposed to theology, and became an opera enthusiast. He caroused with several good friends who called themselves “The Holy Alliance”. They discussed philosophy, girls and the opera, and Søren pretended to be more dissolute and outrageous than he actually was. By this time, he was developing more objective reservations about his father’s extreme religious views, and even entertained serious doubts about his own Christian faith. And like most philosophy students then and now, he was worried about what to do with his life. Philosophy itself certainly didn’t seem to have the answers.

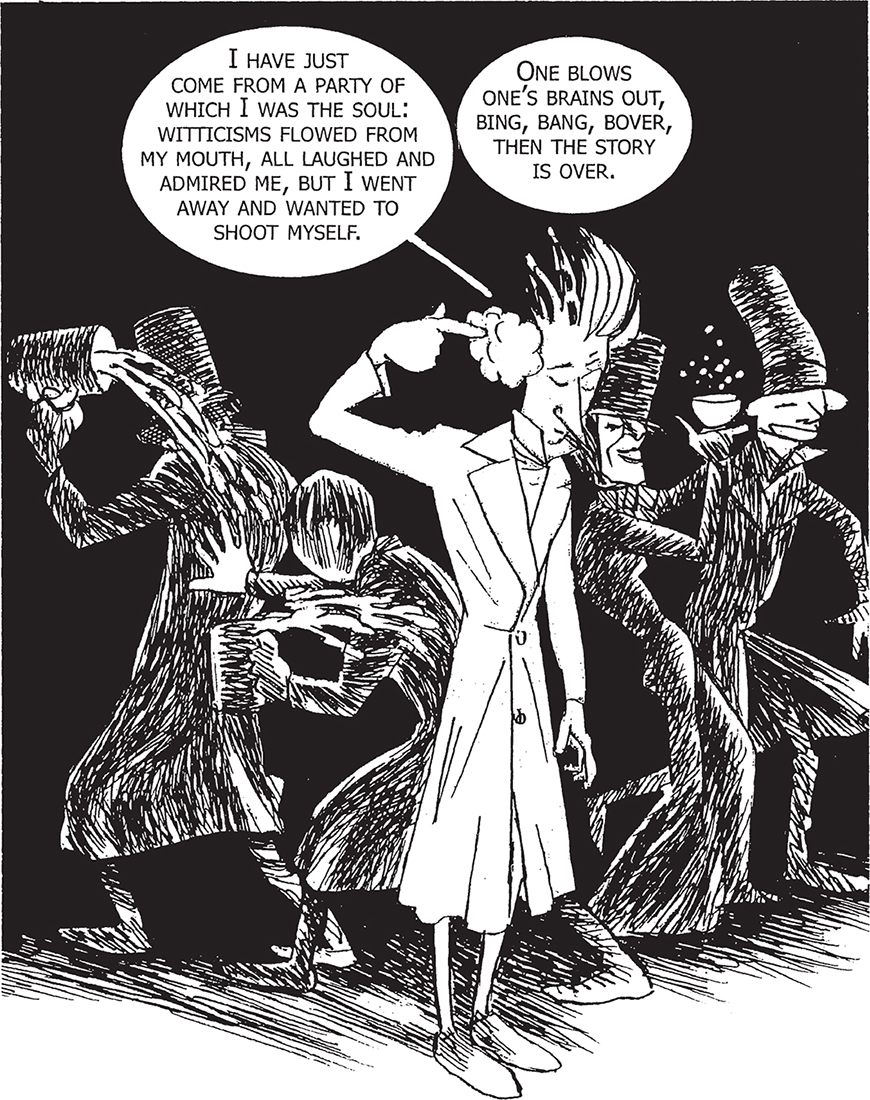

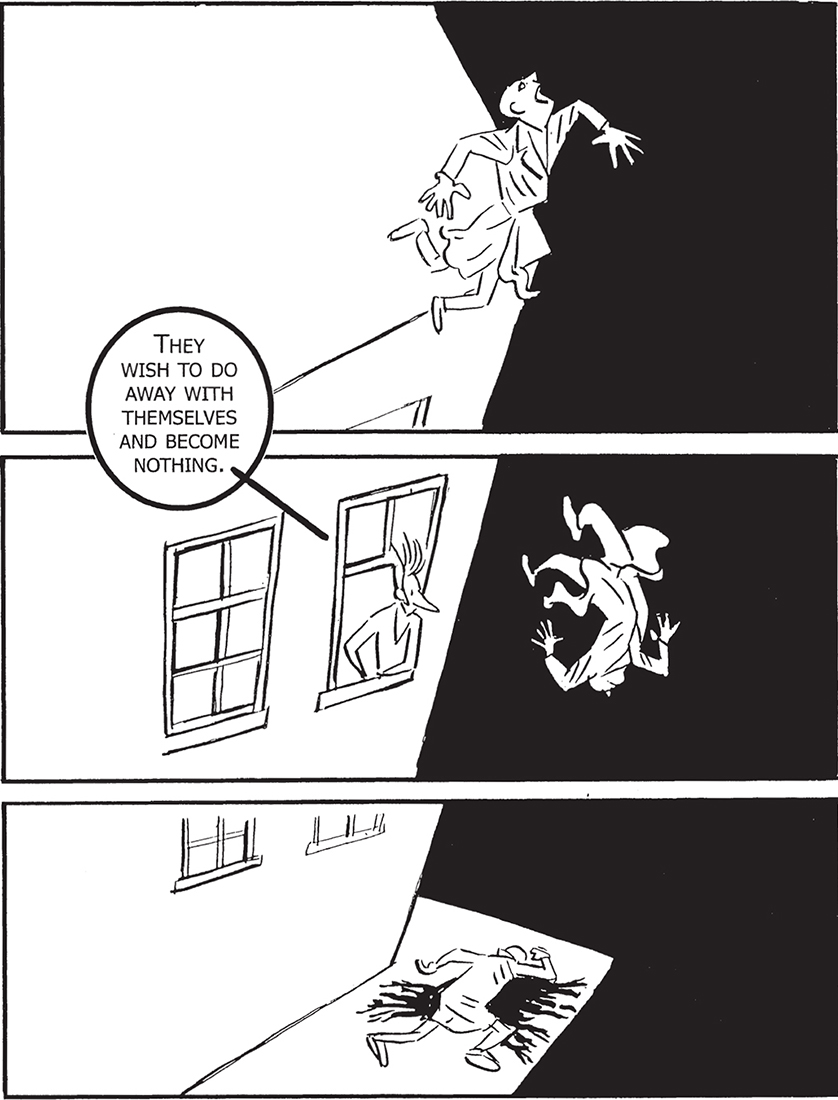

The young Søren was a naturally serious individual, not really cut out for the life of a dissolute rake, even if he did his best. He ran up bills with booksellers, tobacconists and restaurants. He got drunk with his fellow students and maybe even had a sexual experience or two. But the life of pleasure soon came to seem forced and futile. He sank into a deep, almost suicidal despair at his lack of direction, and felt completely remote from the lives of his friends, who all found him wonderfully witty, if rather aloof.

ONE BLOWS ONE’S BRAINS OUT, BING, BANG, BOVER, THEN THE STORY IS OVER.

I HAVE JUST COME FROM A PARTY OF WHICH I WAS THE SOUL: WITTICISMS FLOWED FROM MY MOUTH, ALL LAUGHED AND ADMIRED ME, BUT I WENT AWAY AND WANTED TO SHOOT MYSELF.

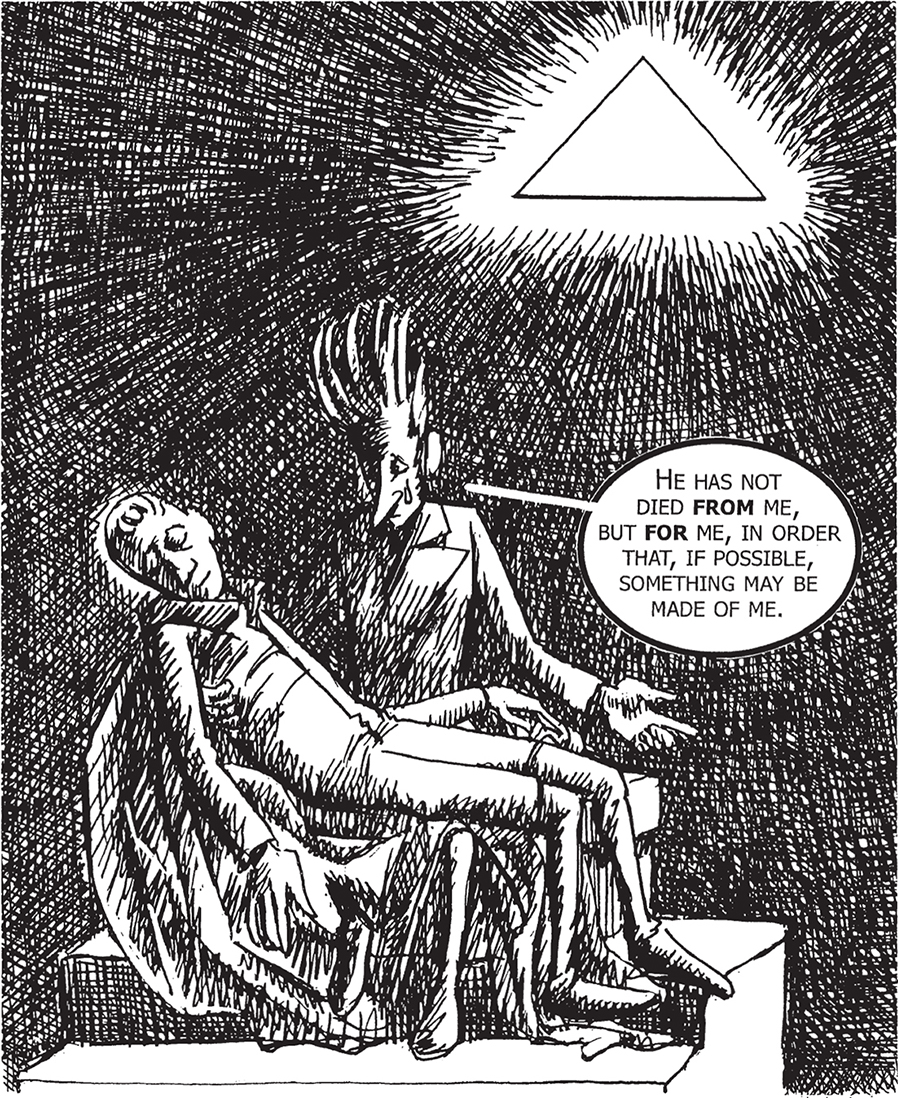

Fortunately, in May 1838, when he was 25, he seems to have had some kind of mystical experience that rekindled his religious enthusiasm. “There is an indescribable joy which blazes in me.” He became reconciled with his now ailing father but, three months later, the old man died. This affected Søren deeply.

He HAS NOT DIED FROM ME, BUT FOR ME, IN ORDER THAT, IF POSSIBLE, SOMETHING MAY BE MADE OF ME.

In his mind, returning to his father and God were more or less the same thing. He came to believe that his father had sacrificed himself so that his son could continue to preach God’s message to the world.

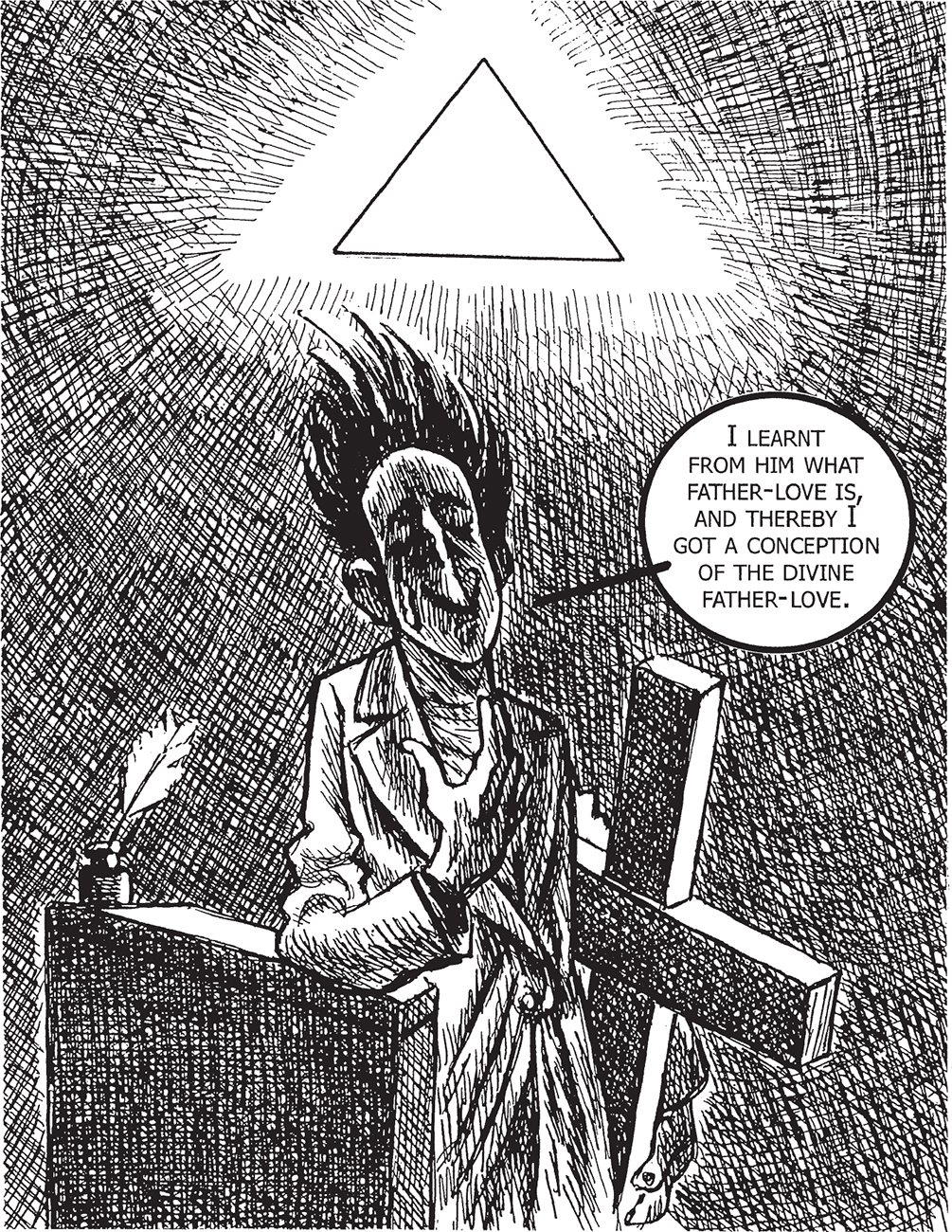

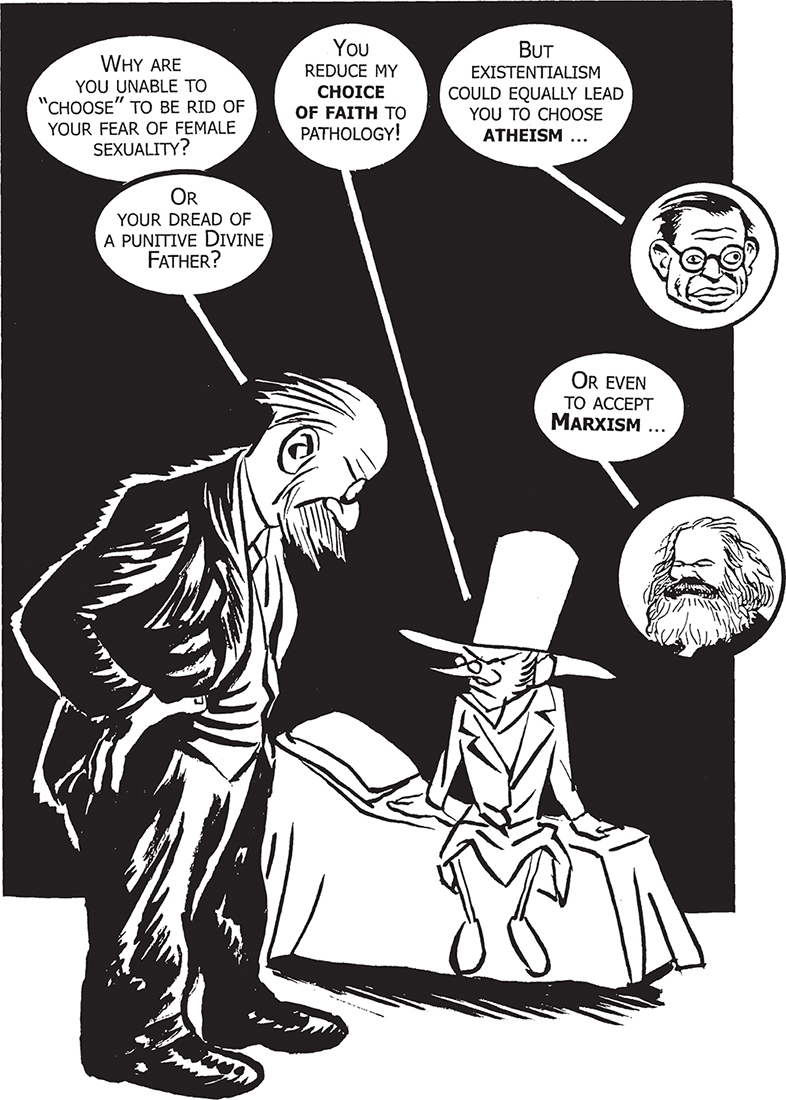

Kierkegaard undoubtedly had some kind of complicated “father fixation”. He projected the personality of his own very odd and stern father onto that of the authoritarian God he wrote about for the rest of his life.

I LEARNT FROM HIM WHAT FATHER-LOVE IS, AND THEREBY I GOT A CONCEPTION OF THE DIVINE FATHER-LOVE.

He also seems to have inherited some of his father’s mental instability. His religious frame of mind was equally obsessive, melancholic and guilt-ridden.

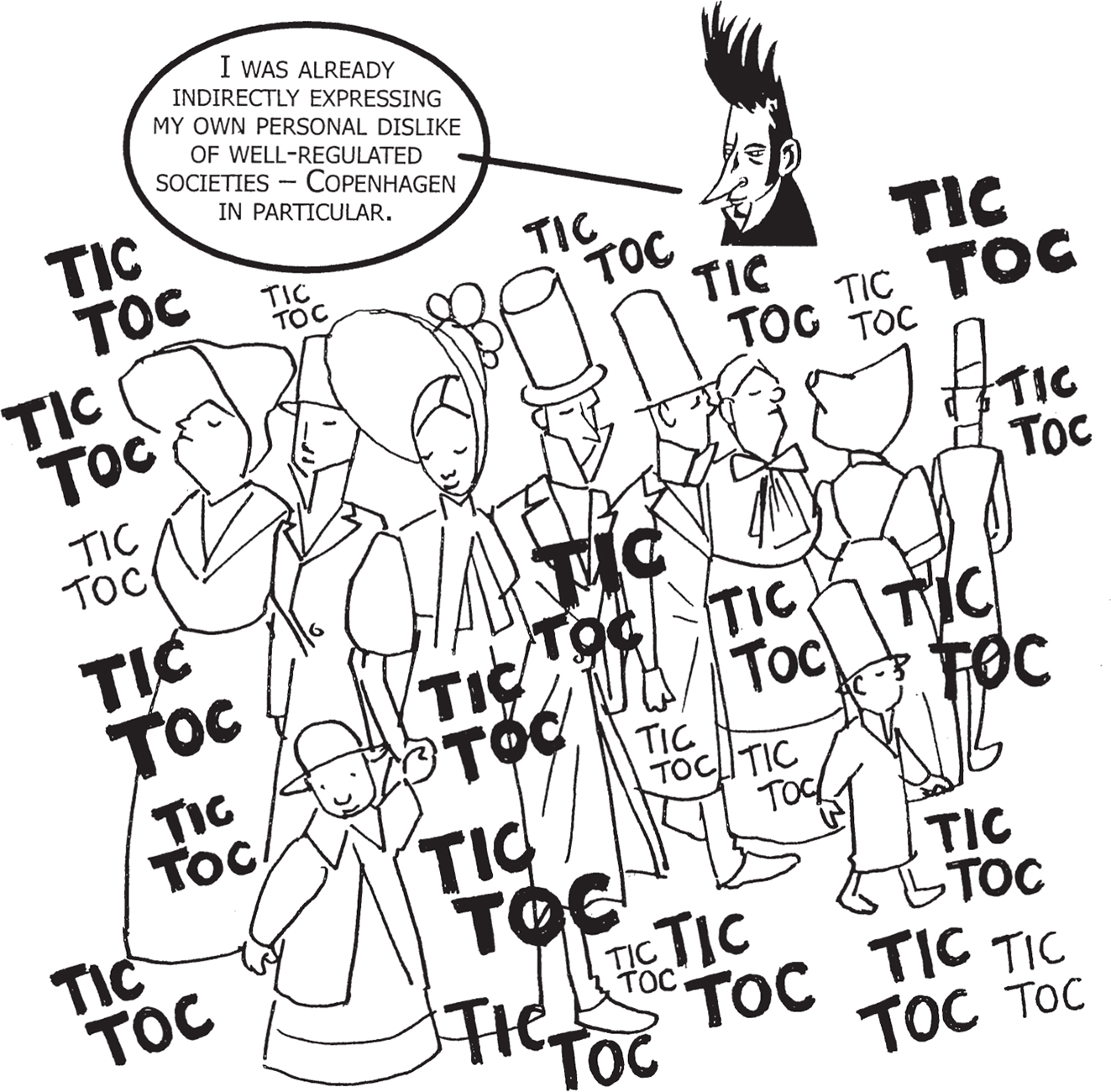

In 1840, after many years of interrupted study, Kierkegaard finally completed his degree in theology and was looking forward to becoming the pastor of a small country parish. He wrote a student thesis, “On the Concept of Irony, with Special Reference to Socrates”. In this essay he praises Socrates for his attacks on conventional ideas and accepted wisdoms, and his impressive ironic detachment. Socrates mocks all those who are “fossilized in their limited social conditions”.

I WAS ALREADY INDIRECTLY EXPRESSING MY OWN PERSONAL DISLIKE OF WELL-REGULATED SOCIETIES – COPENHAGEN IN PARTICULAR.

“Everything was perfect and complete and did not allow any sensible longing to remain unsatisfied. Everything was timed to the minute: You fell in love when you reached your 20th year, you went to bed at ten o’clock. You married, you lived in domesticity and maintained your position in the State. You had children.”

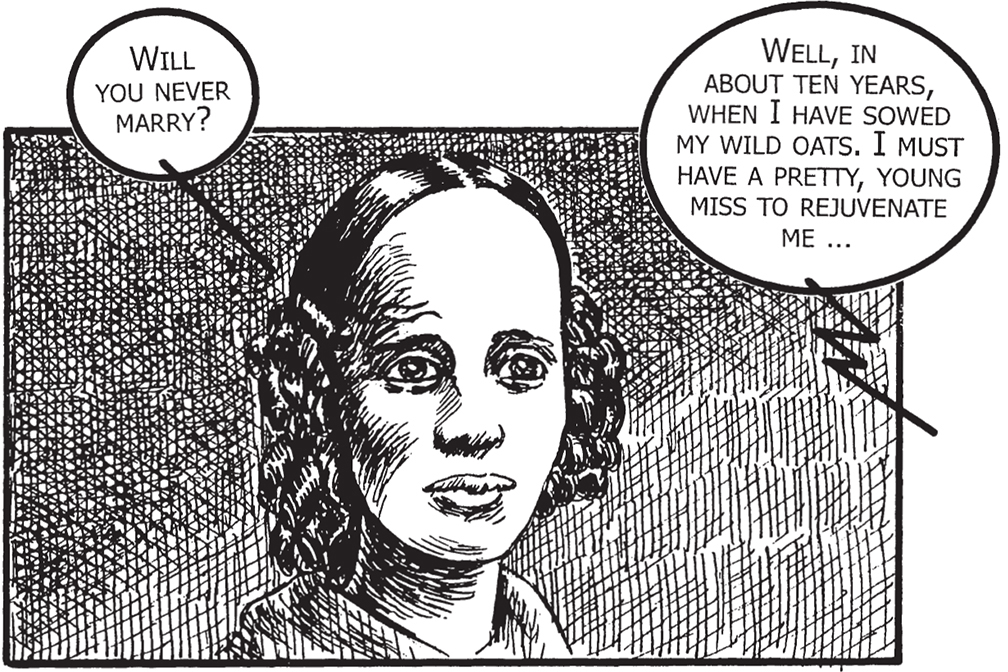

By now Kierkegaard was in love with 18-year-old Regine Olsen. She was both pretty and intelligent, and he had admired her for some time. In September 1840, he proposed to her and was accepted.

HER FATHER SAID NEITHER YES NOR NO, BUT NEVERTHELESS HE WAS WILLING ENOUGH. I ASKED FOR AN OPPORTUNITY TO TALK TO HER. SHE SAID YES.

A formal engagement of one year was agreed upon. So Kierkegaard was well on the way to becoming a highly respectable member of Copenhagen society, as his father would have wished.

But the day after the engagement was announced, he knew he had made a dreadful mistake. He suspected that Regine had accepted him out of pity. Doubts and anxieties flooded into his mind. He was not husband material. His habit of deep thought and reflection made him “a lover with a wooden leg”.

ANY GIRL FOOLISH ENOUGH TO AGREE TO MARRY ME WOULD SOON REGRET IT.

“Inwardly I saw that I had made a mistake. I should have to initiate her into things most terrible, my relationship with Father; his melancholy the eternal darkness which broods in my innermost part, my excursions into lust and debauchery The voice of Judgement said, ‘Give her up.’”

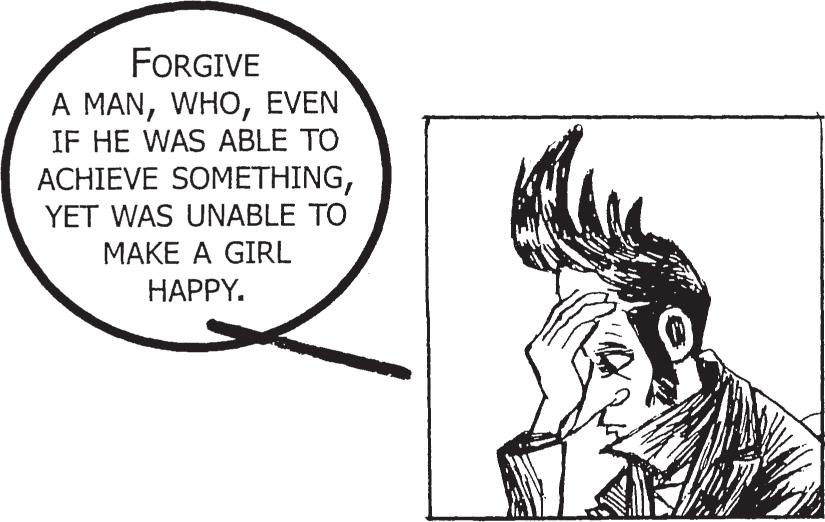

Kierkegaard panicked, broke the “very intellectual relationship” between them and returned Regine’s ring in the following August of 1841.

FORGIVE A MAN, WHO, EVEN IF HE WAS ABLE TO ACHIEVE SOMETHING, YET WAS UNABLE TO MAKE A GIRL HAPPY.

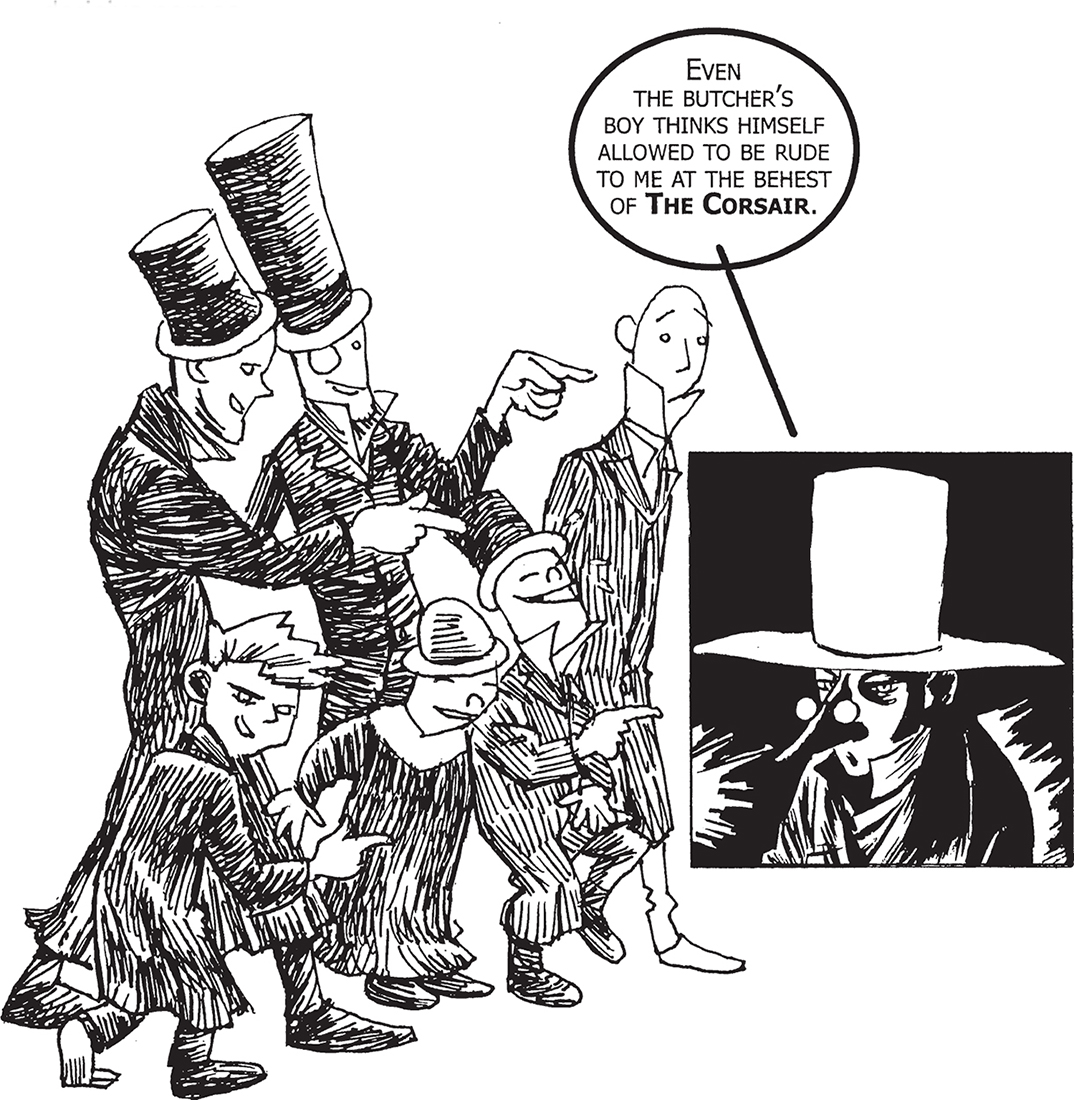

Regine was reluctant to let him go, even though Kierkegaard insisted on telling her all the sordid details of his dissolute student days. He honourably pretended to be a corrupt “scoundrel” and “deceiver of women” so that people would think it was Regine and not he who had broken off the engagement. Copenhagen was a small, gossipy provincial city.

IF A RESPECTABLE GIRL WAS REJECTED BY HER SUITOR, THERE HAD TO BE A SINISTER REASON.

IF A RESPECTABLE GIRL WAS REJECTED BY HER SUITOR, THERE HAD TO BE A SINISTER REASON.

IF A RESPECTABLE GIRL WAS REJECTED BY HER SUITOR, THERE HAD TO BE A SINISTER REASON.

IF A RESPECTABLE GIRL WAS REJECTED BY HER SUITOR, THERE HAD TO BE A SINISTER REASON.

But Kierkegaard would not relent. “So let us suppose I had married her. What then? About me there is something rather ghostly, which accounts for the fact that no one can put up with me. I was engaged to her for a year; and still she did not really know me. I was too heavy for her; and she was too light for me.”

Regine finally gave him up and eventually became engaged to the rather more reliable Johan Frederik Schlegel, an earlier admirer. She remained puzzled and confused about the whole affair.

WILL YOU NEVER MARRY?

WELL, IN ABOUT TEN YEARS, WHEN I HAVE SOWED MY WILD OATS. I MUST HAVE A PRETTY, YOUNG MISS TO REJUVENATE ME …

YOU HAVE BEEN PLAYING A DREADFUL GAME WITH ME.

Kierkegaard escaped from the Copenhagen gossip and a public scandal.

“I journeyed to Berlin. I suffered a great deal. I was so profoundly shaken that I understood perfectly well that I could not possibly succeed in taking the comfortable and secure middle way in which most people pass their lives. But it was she who made me a poet.”

In Berlin, he attended lectures by the Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling (1775–1854). As a determined bachelor, he spent the rest of his life praising the institution of marriage – from a distance. Regine became fictionalized in his mind as a kind of inaccessible muse. The whole sorry episode helped to make him into one of the most remarkable writers and philosophers of the 19th century. He had made up his mind what to do with his life, at last.

I SAT AND SMOKED MY CIGAR UNTIL. I LAPSED INTO THOUGHT. YOU MUST DO SOMETHING. YOU MUST UNDERTAKE TO MAKE SOMETHING HARDER.

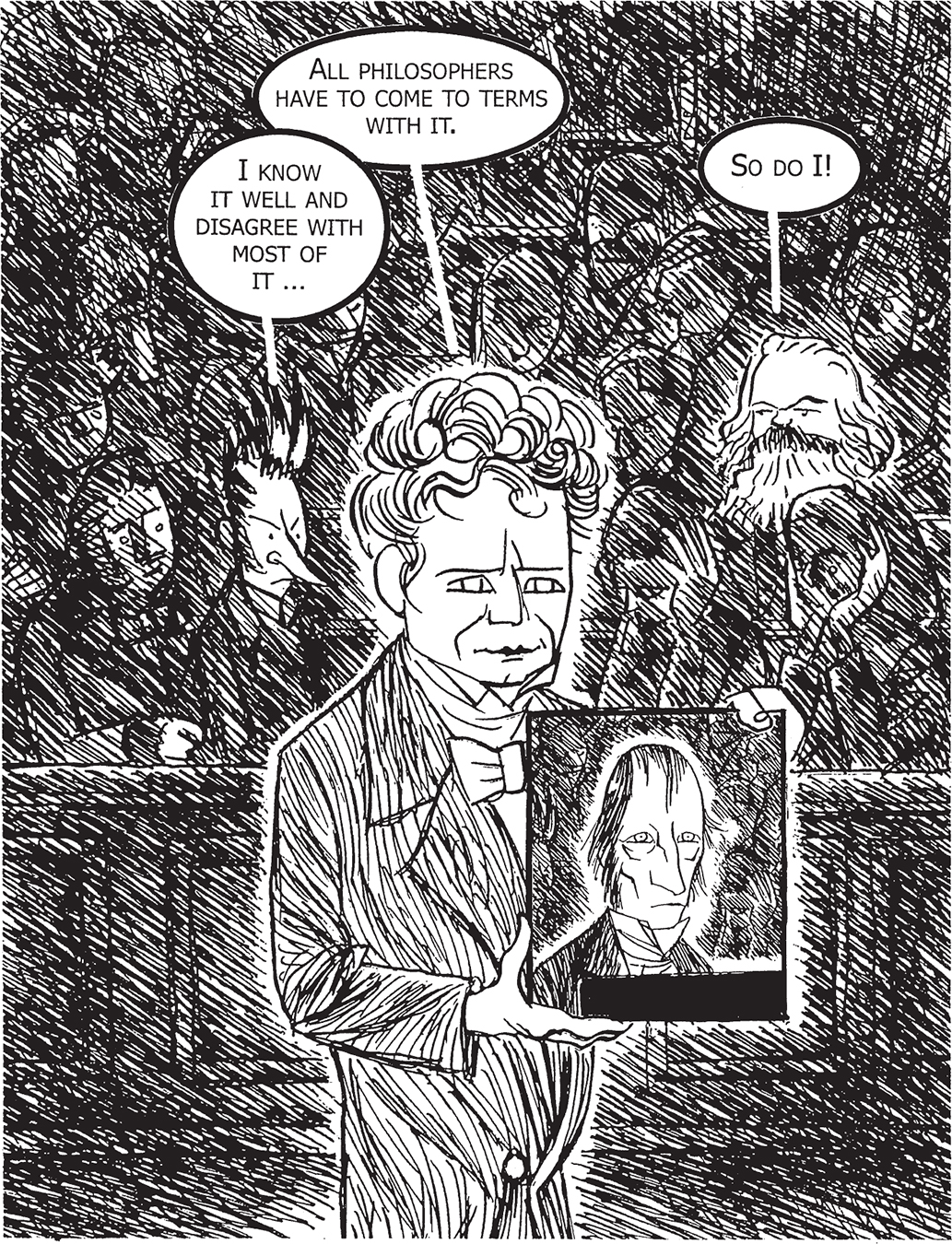

Schelling’s lectures on the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) were also attended by other extraordinary radicals, among them the young Karl Marx (1818–83). The philosophy of Hegel was a powerful influence on all European intellectual life at that time.

So DO I!

ALL PHILOSOPHERS HAVE TO COME TO TERMS WITH IT.

I KNOW IT WELL AND DISAGREE WITH MOST OF IT …

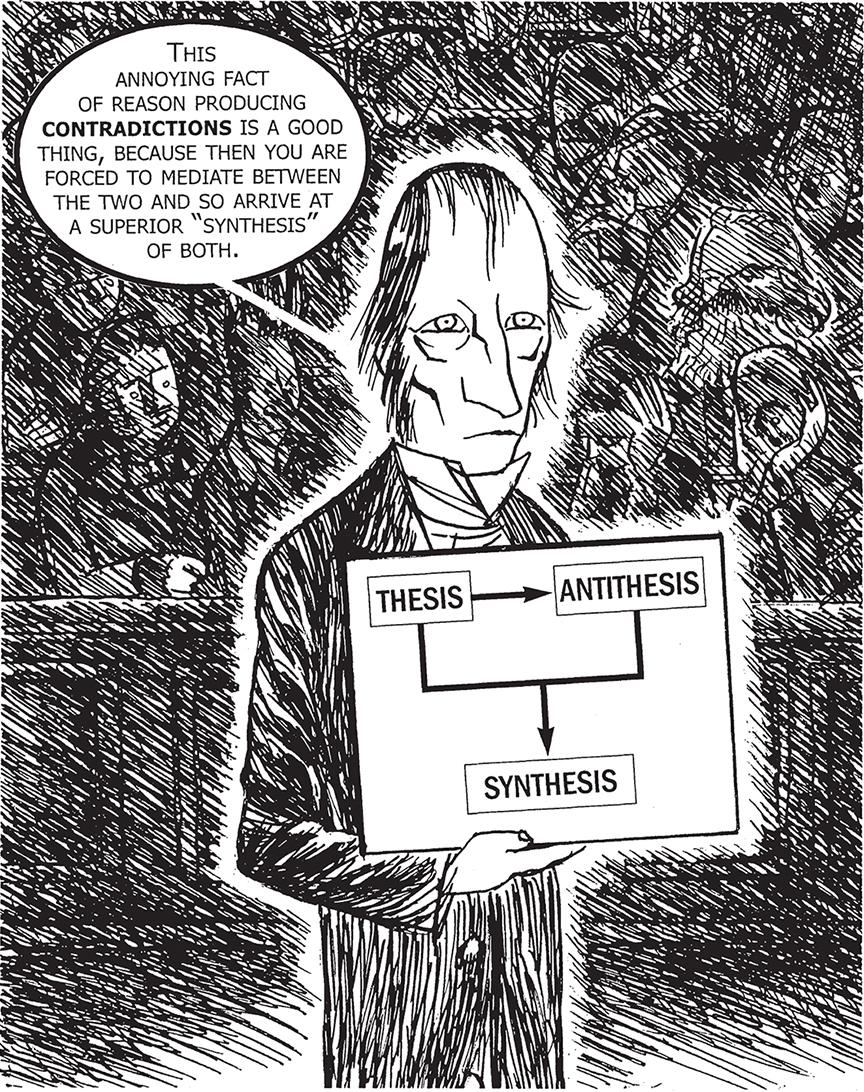

What was Hegel’s philosophy and why was it so influential?

Hegel believed that “Reason” is the best method of finding out the truth. But getting there was a complicated process. When you employ reason to investigate the world and its human inhabitants, you frequently end up with conclusions that seem utterly opposed.

THIS ANNOYING FACT OF REASON PRODUCING CONTRADICTIONS IS A GOOD THING, BECAUSE THEN YOU ARE FORCED TO MEDIATE BETWEEN THE TWO AND SO ARRIVE AT A SUPERIOR “SYNTHESIS” OF BOTH.

This synthesis cancels out the superficial conflict between contradictions, preserves the element of truth in both and so helps advance the inevitable progress of human rational thought towards the “Absolute Truth”.

I NEVER SAID THAT MY PHILOSOPHY WOULD GET THAT FAR. INDEED, I STRESSED HOW HUMAN KNOWLEDGE WAS INEVITABLY HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL, NOT TIMELESS AND ETERNAL.

Nevertheless, the process of “dialectic mediation” gets repeated throughout history, so that, in the end, human reason should be able to progress from lower levels of awareness until it reached the absolute truth about everything – human history, society, psychology, politics and religion. It was an evolutionary account of human knowledge and potential that appealed to many theologians, and even more to philosophers.

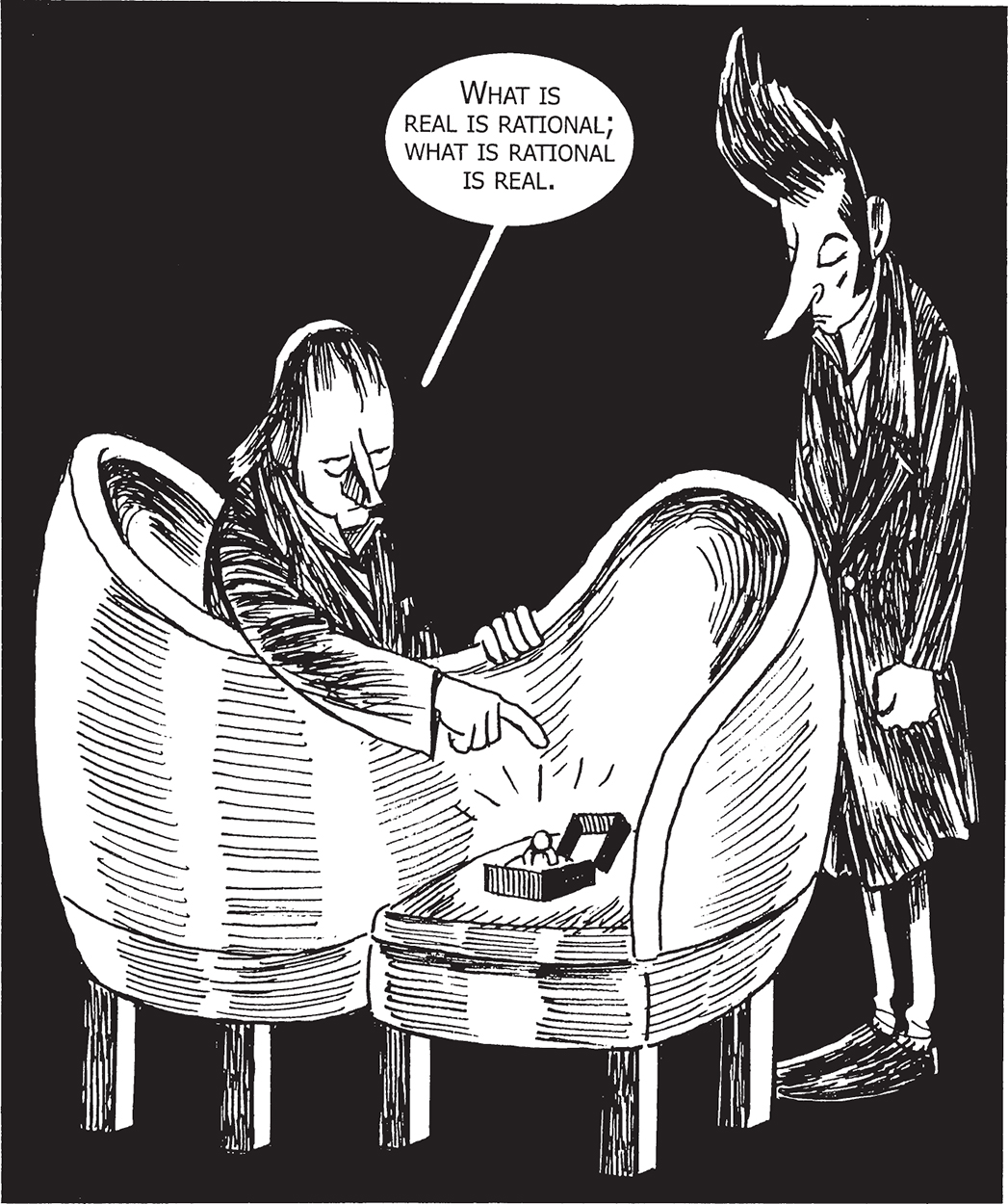

Hegelian dialectics is a logic of “ontology” (what is real) and idealist metaphysics (what is “really real”). It also dissolves the usually rather obvious distinctions that most people make between real objects in the world and human thought.

WHAT IS REAL IS RATIONAL; WHAT IS RATIONAL IS REAL.

Hegel argued that we need both mental concepts to categorize and explain the world of things as they appear to us, and things to give us something to think about. This means that “reality” must consist of both thoughts and objects, so the words “exist” and “real” take on rather odd all-inclusive meanings in Hegelian jargon.

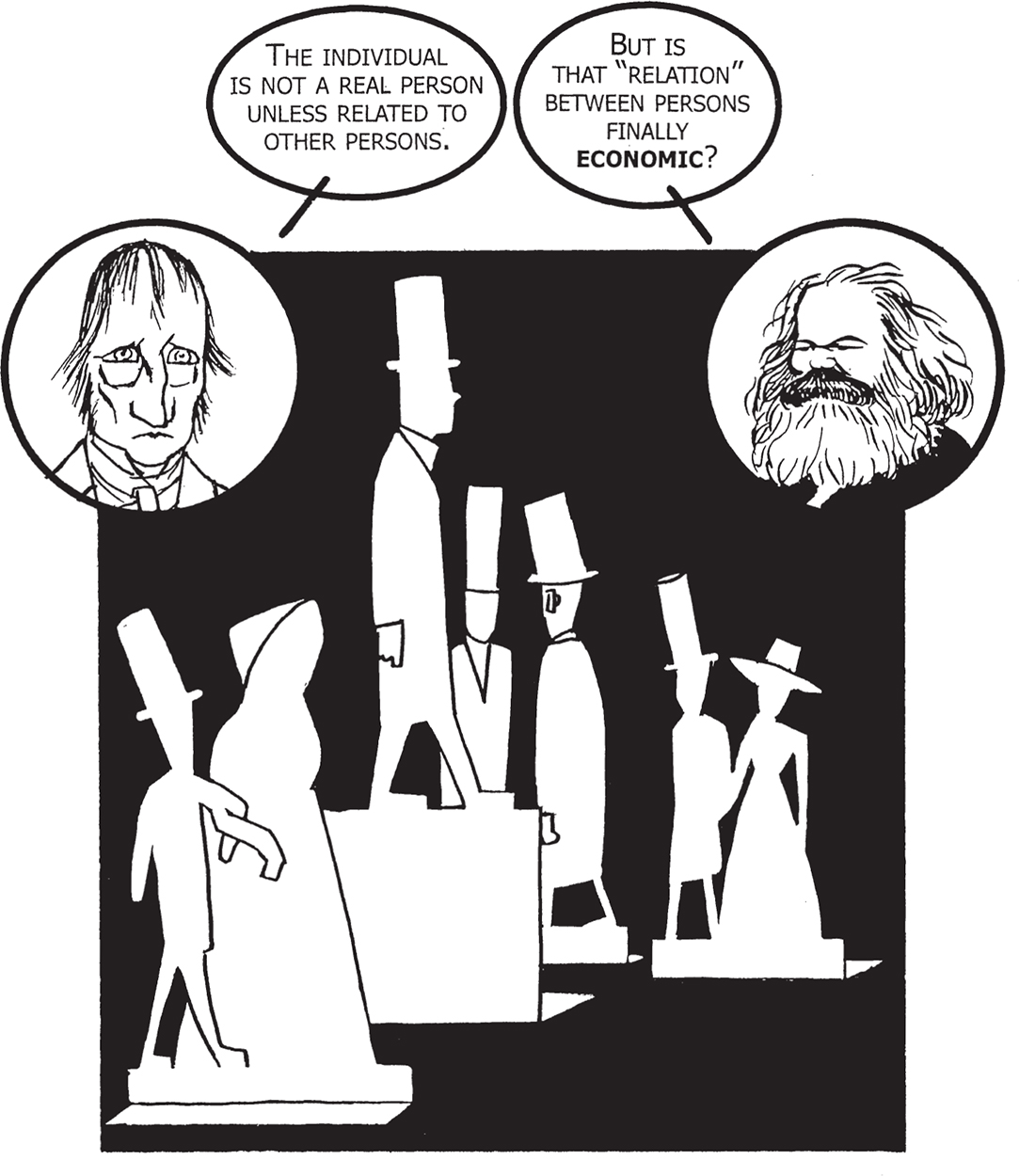

But it was Hegel’s views on society and the individual that most exercised Kierkegaard. Hegel was impressed by how modern 19th-century civil society had progressed. The more society advanced, the greater was everyone’s understanding and acceptance of individual rights and freedoms. But society had to be more than just a collection of individuals engaged in commercial dealings with each other.

HUMAN FREEDOM MUST MEAN SOMETHING MORE THAN JUST THE FREEDOM TO TRADE.

THE STATE HAS TO BECOME SOMETHING MORE THAN JUST A “NIGHT-WATCHMAN” OF THAT FREEDOM.

In Hegel’s ideal society, the will of each individual and society’s laws must coincide, because, ultimately, human beings are defined by their relation to others. That’s why it was conceptually impossible to “resign” from society or claim that you were some kind of “outsider”.

BUT IS THAT “RELATION” BETWEEN PERSONS FINALLY ECONOMIC?

THE INDIVIDUAL IS NOT A REAL PERSON UNLESS RELATED TO OTHER PERSONS.

The conclusion of this Hegelian “system” is that the individual must be subordinated to the family unit, the family to society, and society to the State.

Kierkegaard was initially overwhelmed by the immensity and scope of Hegelian philosophy, but soon became disillusioned. Hegel’s dialectic seemed to be a process of predetermined necessity in which individual choice was illusory or irrelevant. It was a world described from “outside” and had little to say to the young Kierkegaard trying to find out how to live.

THE ONE THING THAT HAS ALWAYS ESCAPED HEGEL IS – HOW TO LIVE. IT’S LIKE READING OUT OF A COOKBOOK TO A MAN WHO IS HUNGRY.

Kierkegaard’s objections weren’t just peculiar to his own personal situation. He went on to attack Hegel’s “system” on purely philosophical grounds. He had a deep distrust of any philosophy that promised to be all-inclusive. Hegel’s philosophy also seemed predominantly “backward looking”. It had a “world historical” point of view but ignored how actual individuals live their lives – in the present, continually faced with decisions about their future.

IT IS PERFECTLY TRUE THAT LIFE MUST BE UNDERSTOOD BACKWARDS. BUT IT MUST BE LIVED FORWARDS.

Hegel was simply too theoretical – obsessed by huge abstract concepts at the expense of particular real-life human beings who can never be reduced to mere concepts.

IF A PHILOSOPHY CANNOT TELL US HOW TO LIVE, THEN IT IS OF NO USE OUTSIDE ACADEMIC LIFE.

Philosophers had too long concentrated on the idea of “humanity” and ignored the fears, desires, thoughts, dispositions, neuroses and commitments of individual human beings.

For Kierkegaard, discovering the “truth” is not just about finding out how things are. It’s more a matter of making a commitment and taking specific kinds of action. Philosophy has to be more than just a calm search for objective truth.

IT HAS TO BE A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO LIVING, EVEN IF IT CANNOT TELL YOU EXACTLY WHAT TO DO.

Individual human beings constantly find themselves in a state of “paradox” (a crisis that needs to be resolved) and hope to find a “truth” (a resolution of the crisis, after making a commitment to a particular kind of action).

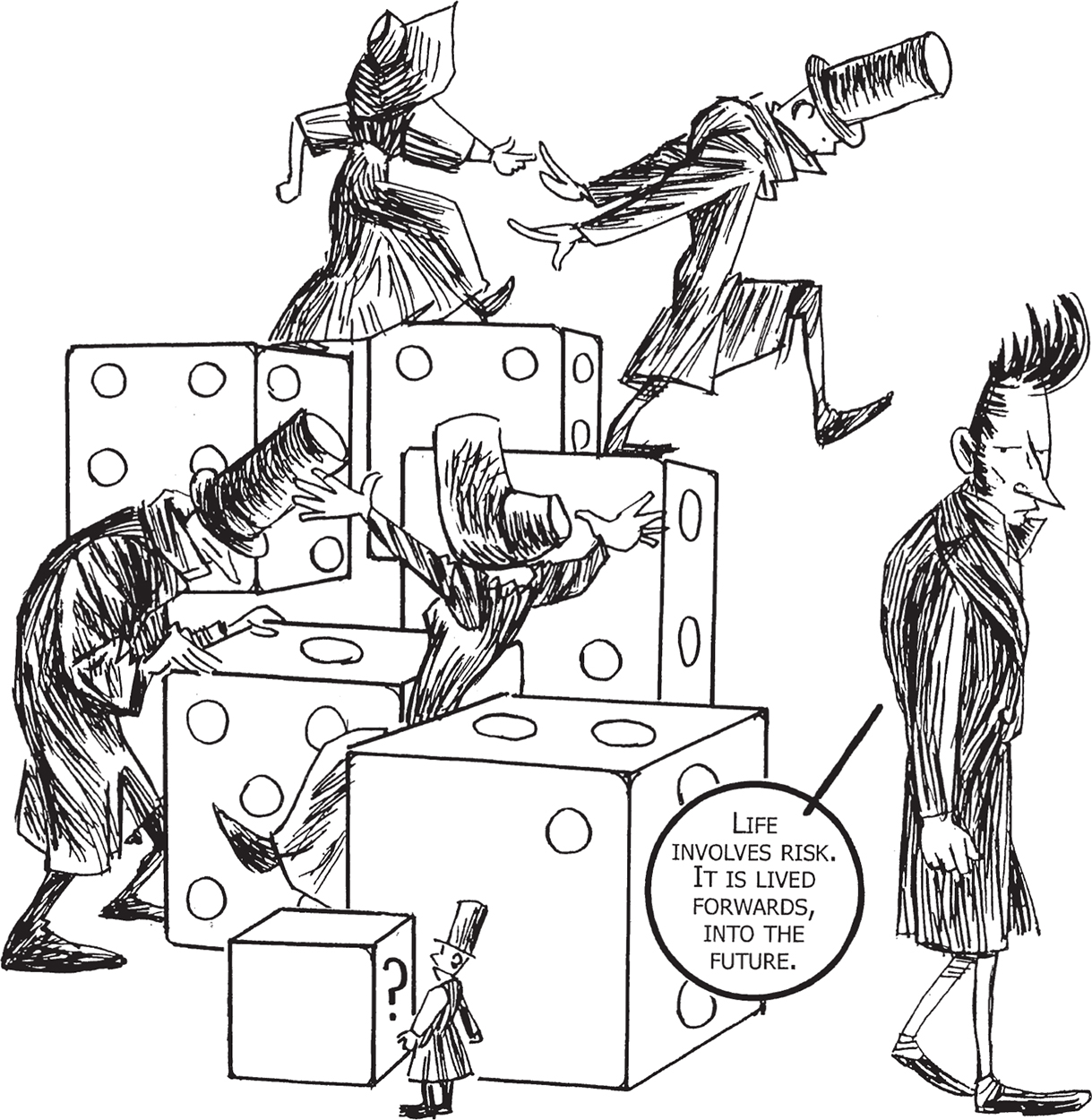

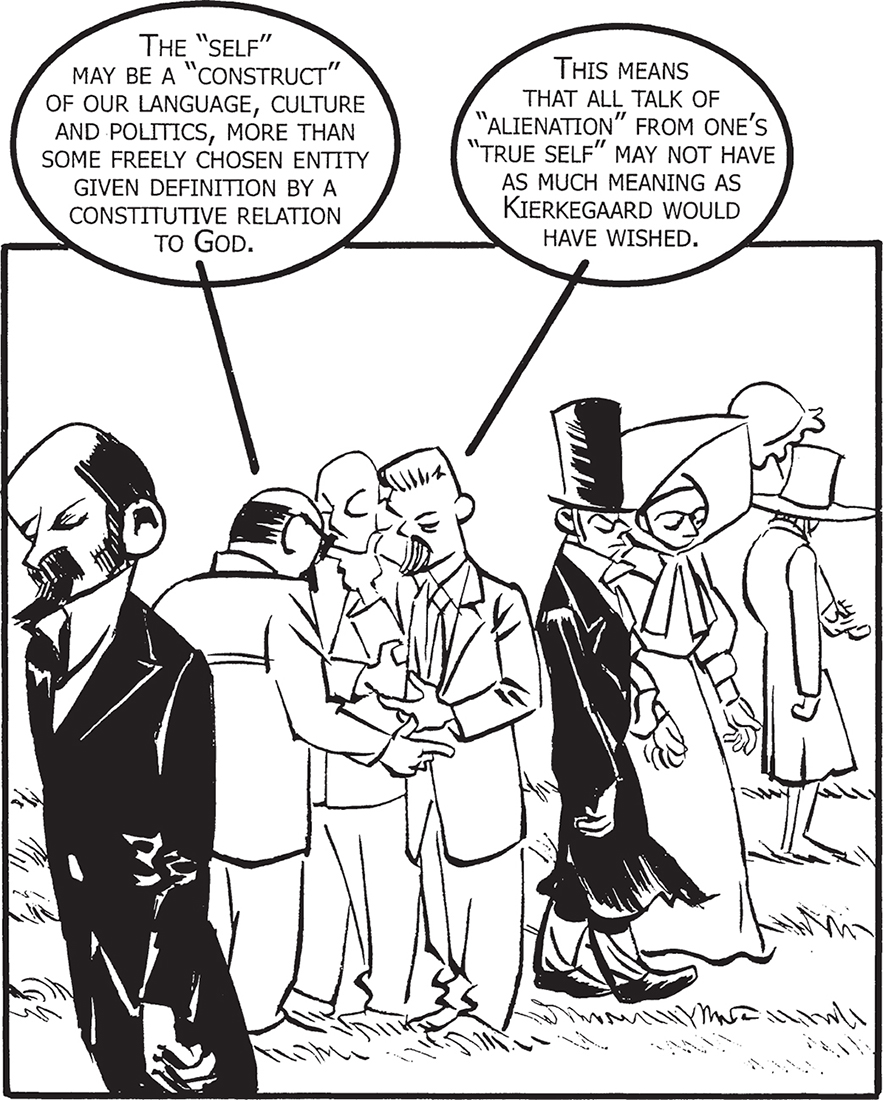

Fictional characters in plays and novels are already provided with a “character” or “essence” that determines their destiny. With real people, the opposite is true. It is their chosen actions that cumulatively determine their character over time. In order to live and not aimlessly drift through life, you have to choose a specific “sphere of existence” – and that is always a gamble. It often requires immediate decisions and implies a commitment to act in certain kinds of ways in the future. Living is not an activity that can be “mediated” by some ongoing dialectic.

LIFE INVOLVES RISK. IT IS LIVED FORWARDS, INTO THE FUTURE.

So it is not possible to wait until afterwards and subject it to analysis and synthesis.

Kierkegaard’s attack on Hegelianism has its attractions.

ANYONE WHO ONCE DESCRIBED HEGELIAN JARGON AS “TALKING WITH ONE’S MOUTH FULL OF HOT MUSH” GETS MY VOTE.

But Kierkegaard’s criticisms are sometimes off the mark. Hegel openly admitted the inadequacies of his own philosophy. How could it possibly tell each individual how to live a particular life? Kierkegaard’s own philosophy can sound dangerously “Hegelian” with its talk of “stages” and the attractions of the “universal”. But the philosophies of Hegel and Kierkegaard seem wholly incommensurate. Kierkegaard’s work is an “anti-philosophy” that rejects virtually the whole canon of Western philosophy with its emphasis on what is universal and objective, and on what can or cannot be known. Kierkegaard is playing a wholly different “language game” to Hegel. This makes it very difficult for anyone to analyze or criticize one in the terms employed by the other.

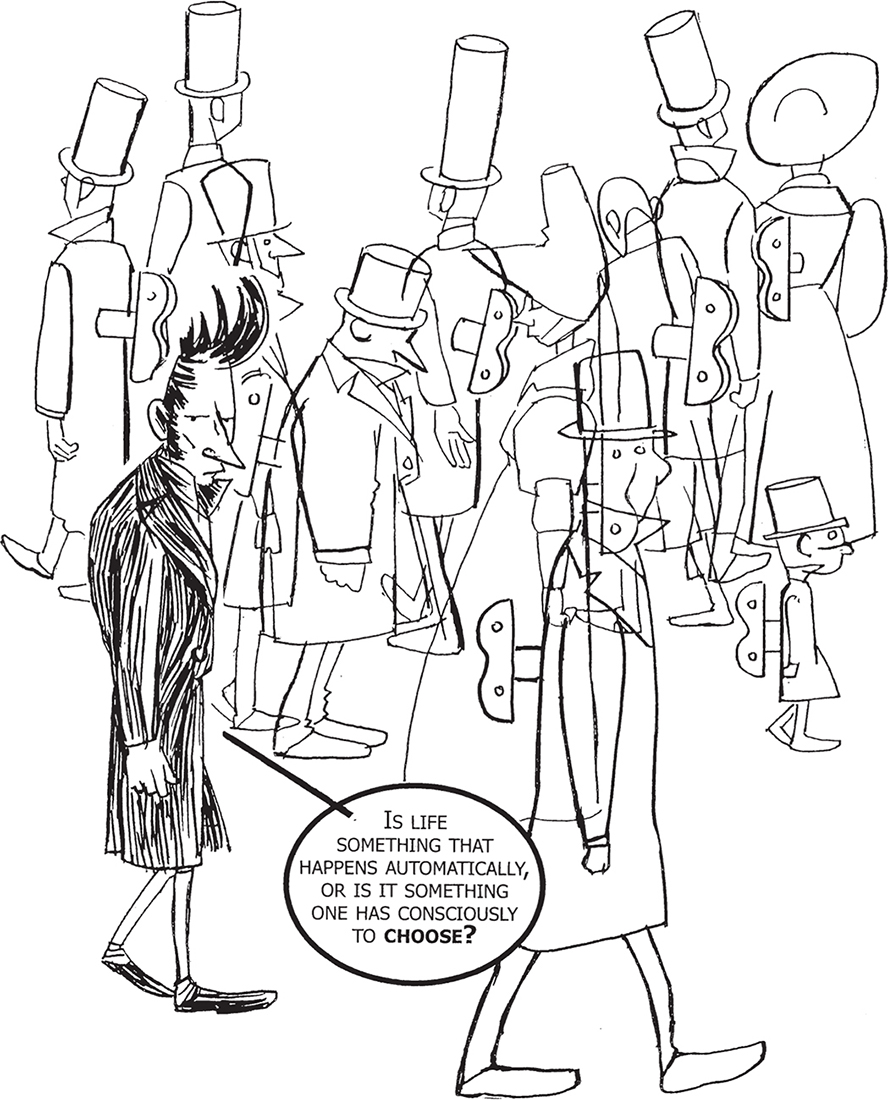

Kierkegaard returned to Copenhagen. He had finally come to realize that he was a natural “outsider” for whom the usual destinations of marriage and career were unavailable. Having rejected one specific way of life, he was naturally thinking about what it means to “choose” a specific way of life, and whether or not some forms of existence are superior to others.

Is LIFE SOMETHING THAT HAPPENS AUTOMATICALLY, OR IS IT SOMETHING ONE HAS CONSCIOUSLY TO CHOOSE?

Kierkegaard saw that most people were content to be absorbed into the everyday world of marriage, career and respectability. Most people follow the normal practices of their society. If the society is Christian, then they go to church. If it is communist, then they dutifully attend party meetings. That doesn’t make them hypocrites, because they have probably never thought of questioning the social and economic pressures that govern their daily thoughts.

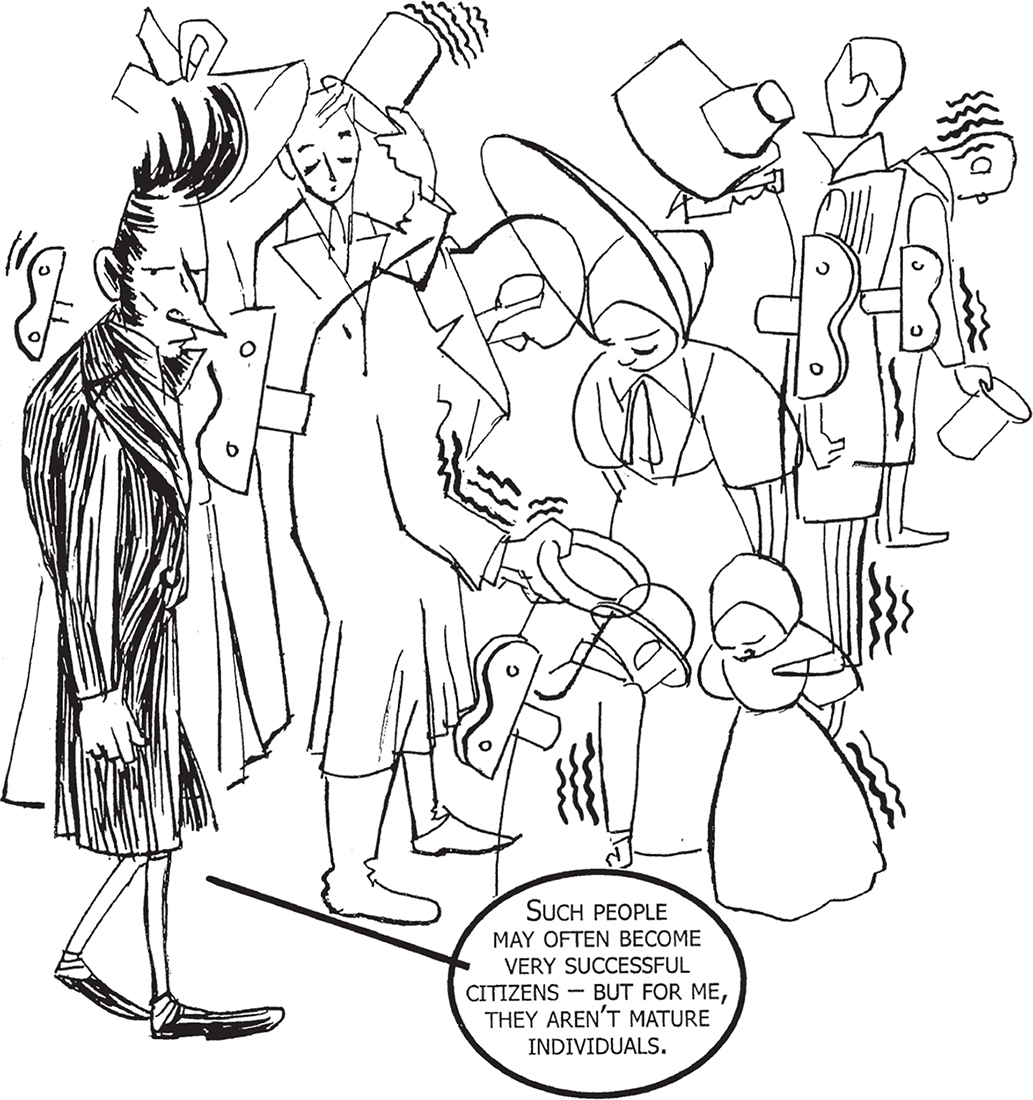

SUCH PEOPLE MAY OFTEN BECOME VERY SUCCESSFUL CITIZENS – BUT FOR ME, THEY AREN’T MATURE INDIVIDUALS.

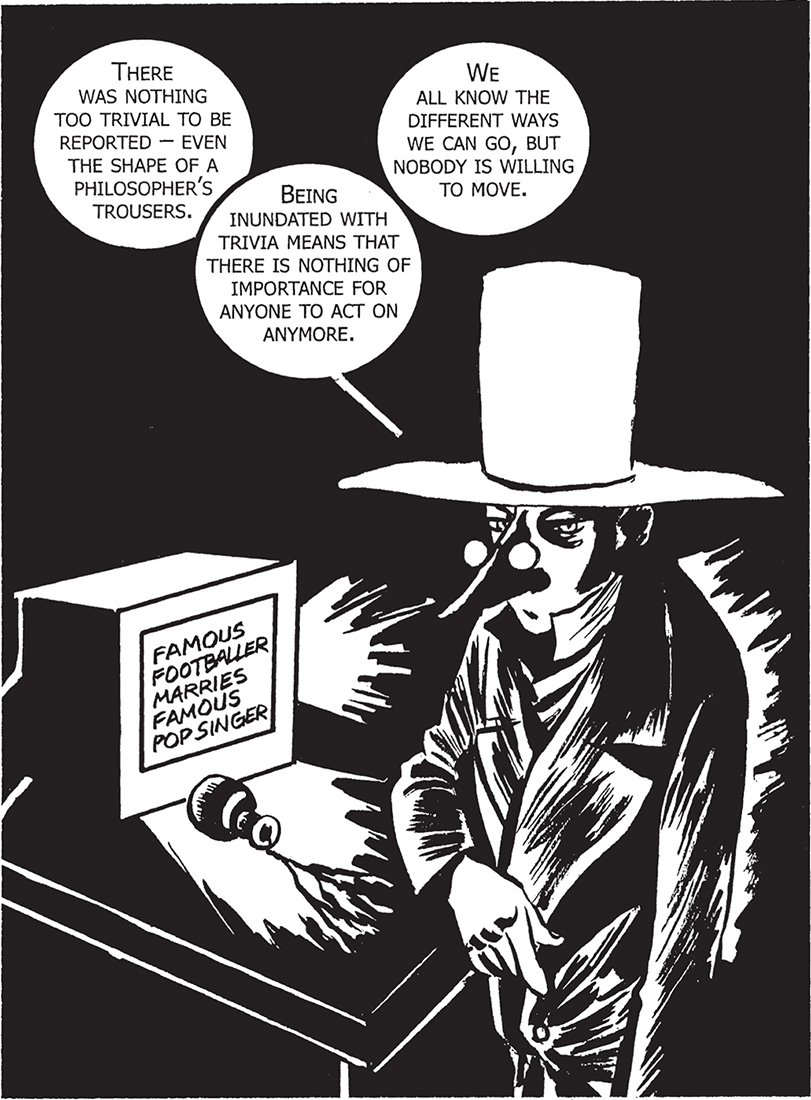

“Everything must be reduced to the same level by producing a phantom, a monstrous abstraction, an all-embracing something that is nothing, a mirage, and that phantom is ‘the public’.”

The “crowd” have avoided all self-conscious reflections about the sort of life they lead. Kierkegaard mentions many examples of such “philistines”.

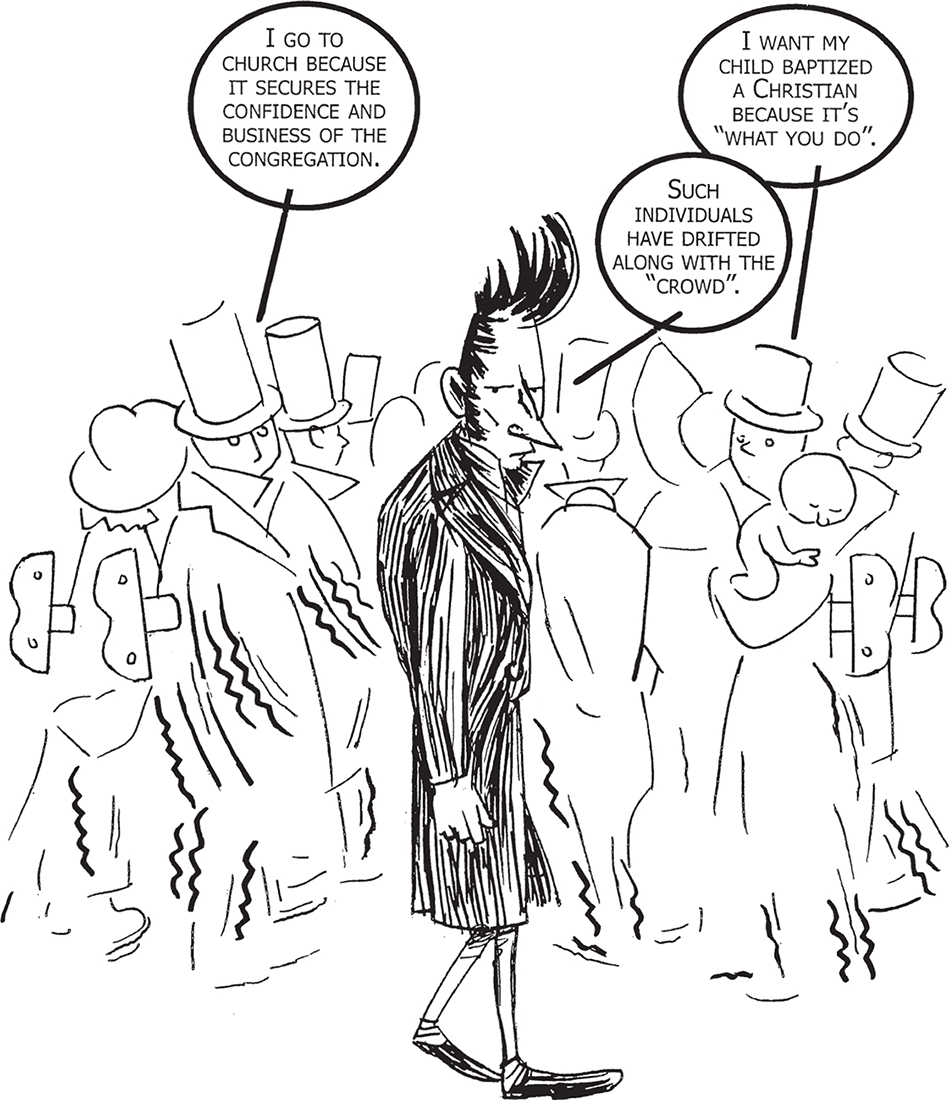

I GO TO CHURCH BECAUSE IT SECURES THE CONFIDENCE AND BUSINESS OF THE CONGREGATION.

I WANT MY CHILD BAPTIZED A CHRISTIAN BECAUSE IT’s “WHAT YOU DO”.

SUCH INDIVIDUALS HAVE DRIFTED ALONG WITH THE “CROWD”.

They are contented members of the “public” but lack any real personal freedom, because they have allowed others to decide how they should live.

Kierkegaard had chosen his own rather different way of life. He had made up his mind about his future at last.

I UNDERSTOOD PERFECTLY THAT I COULD NOT POSSIBLY SUCCEED IN TAKING THE COMFORTABLE AND SERENE MIDDLE WAY IN WHICH MOST PEOPLE PASS THEIR LIVES.

His father had left him a substantial legacy, which meant that he could become a full-time writer. His first real book Either/Or was published pseudonymously on 20 February 1843 and immediately became a literary sensation.

This book is a very odd mixture of puzzling prefaces, forewords, interludes, postscripts, appendices, letters, poems and diaries. There is no one declared “author” of the book but several. It is a wildly exuberant text, full of totally contrasting ideas about relationships, religion, marriage, seduction, metaphysics and art. Publishing under numerous pseudonyms became a habit for Kierkegaard, done partly to avoid yet more scandal. But he also wanted to create an “indirect” series of narratives told by different voices with different lives and opposed moral values.

THE INDIVIDUAL HAS MANIFOLD SHADOWS, ALL OF WHICH RESEMBLE HIM, AND FROM TIME TO TIME HAVE EQUAL CLAIM TO THE MAN HIMSELF.

By wearing a series of fictional “masks”, Kierkegaard could also speak out more clearly and dramatically, and let each character be wholly consistent in his views. What puzzled Kierkegaard’s Danish readers was the lack of an overriding “authorial voice” in the book, one that finally steers the reader towards some sort of moral consensus.

I AM DETERMINED TO WRITE AN “OPEN” TEXT, PARTLY BECAUSE HUMAN BEINGS AND THEIR LIVES CAN NEVER BE “CLOSED” LIKE A PIECE OF LOGIC OR MATHEMATICS.

The lives of his characters are extreme, so there is no possibility of a Hegelian synthesis or reassuring “middle ground”. That’s why the book has its eccentric title Either/Or – because “Both-And” is the way to hell.

Deciding upon which individual characters to admire and condemn is a more engaging exercise than arbitrating between abstract ideas. Some readers enjoy this disorientation process and the space it leaves for their own thoughts and opinions. Others like to be told what to think. But the choice remains resolutely either/or, not both/and, because this is what life is like.

You EITHER MARRY THE GIRL OR YOU DON’T. THERE’S NO HALFWAY.

Kierkegaard hoped that his book would help Regine to “push her boat from the shore”. But he never forgot her and regretted never having a second chance to marry her. He wrote about her, indirectly, for the rest of his life, and finally left her everything in his will.

Either/Or is edited by “Victor Eremita”, a detached spectator of the world around him and a shrewd observer of his fellow human beings. He introduces us to a whole series of articles by “Aesthete A” about Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni, modern and ancient tragedy, three fictional “betrayed women”, a review of a comic play, a strange essay on “How to Defeat Boredom” and the extraordinary “Diary of a Seducer” written by someone called “Johannes”.

EITHER/OR BEGINS BY EXAMINING WHAT IT MEANS TO LIVE THE LIFE OF AN AESTHETE, A LIFE DEVOTED EXCLUSIVELY TO SENSATION AND IMMEDIATE PLEASURES.

One of the main themes of the book is seduction. Don Juan – or Giovanni in Mozart’s opera – is a spontaneous seducer of hundreds of women and has a “demonic zest for life”. He has no moral principles and is indifferent to the suffering he causes to nearly everyone he encounters. He refuses to reflect on what he does, because, if he did, he would have to choose – to repent or carry on, but thereafter as a consciously unprincipled womanizer.

HIS CHARACTER IS SO ELEMENTAL THAT IT CAN BE TRULY EXPRESSED ONLY THROUGH MUSIC.

THIS POWER, THIS ENERGY, CANNOT BE EXPRESSED IN WORDS. MOZART UNDERSTOOD THIS.

Johannes the Seducer is a more dubious character because he is reflective. He’s well educated, intelligent and wholly aware that he has “a philosophy of life”. “I refuse to be bored and will devote myself solely to sensual pleasures.” He too is an outsider, which means he is not an unthinking “philistine”. He is, however, a calculating rake who takes pleasure in the chase rather than the end result. His “Diary” tells us in great detail how he secretly investigates the weaknesses of his intended victim “Cordelia”.

I SOON PERSUADE THE IMPRESSIONABLE GIRL TO ACCEPT MY UNORTHODOX DOCTRINE OF “FREE LOVE”.

“We need no ring to remind us that we belong to one another. We drive into the sky through the clouds, the wind whistles around us. If you are giddy, my Cordelia, hold me close.”

His poetic outpourings convince her and get her to the point where she virtually “seduces” herself. He sleeps with her and then immediately abandons her. He tries to persuade us of his good intentions.

I HAVE “DEVELOPED” CORDELIA BY GIVING HER A NEW “EXPERIENCE”.

He claims to be an “honourable” man, because he never promised to marry anyone, and never told lies. He appears to be self-deceived, not only alienated from the world and those around him, but also from himself.

The philistine is formed wholly by his social and economic environment, the aesthete by his natural instincts and feelings. But neither lifestyle is ultimately satisfactory. A life that is restricted to enjoyment and pleasure ends in despair, regardless of all the clever strategies the aesthete employs to fight off boredom.

IT APPEARS THAT EVERY AESTHETIC VIEW OF LIFE IS IN DESPAIR, AND THAT EVERYONE WHO LIVES AESTHETICALLY IS IN DESPAIR, WHETHER HE KNOWS IT OR NOT.

The aesthetic life is, in the end, a series of repetitive experiences that gradually lose their allure, because every individual has a sense of the eternal which this sort of self-indulgent life can never satisfy. Time passes, and the young aesthete, “A”, sees nothing more than duplication and death staring him in the face.

In a series of aphorisms in the section called “Diapsalmata” (“Musical Interludes”), this chosen way of life is revealed as empty and pointless, an endless dabbling with different art forms, people and careers.

FOR THE MOMENT, IN THE SAME MOMENT, EVERYTHING IS OVER, AND THE SAME THING REPEATS ITSELF ENDLESSLY.

The Aesthete is extremely funny on the subject of “boredom”. But because, unlike the vigorous Don Juan, he is a reflective intellectual, he is horrified by the egotistical nastiness of Johannes and able to examine what it means to live according to this self-centred world-view. He bitterly rejects the conventions of society that would force him into a dull marriage and onerous social conformity. But he is also very aware of the vanity of the temporal world – the source of all of his immediate short-lived pleasures.

WHAT IS YOUTH? A DREAM. WHAT IS LOVE? THE CONTENTS OF THE DREAM.

Very quickly, his way of life becomes more of an escape than a search. He drives out feelings of boredom and despair with short-term pleasures punctuated by long periods of lethargy and cynical pessimism.

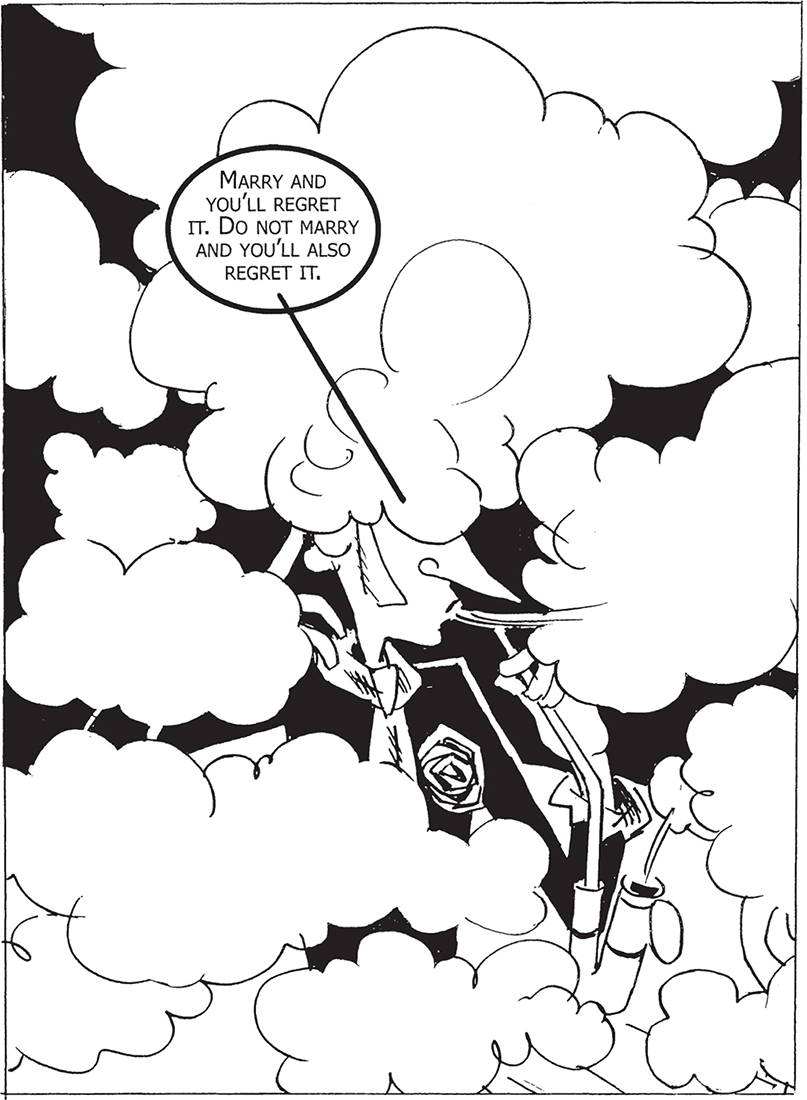

MARRY AND YOU’LL REGRET IT. Do NOT MARRY AND YOU’LL ALSO REGRET IT.

So what is he to do? Rejoin the hordes of unreflecting philistines?

In part two of Either/Or, Judge Wilhelm appears with a vision of another “sphere of existence” for the despairing aesthete.

A life devoted merely to pleasure is doomed. Eventually the young man will run out of new sensations and his wealth and talents will fade away. Judge Wilhelm points out that “A” will always be unhappy because he will be forever trapped in reminiscing about past pleasures or hoping for new ones.

WHAT YOU CAN NEVER DO IS LIVE IN THE PRESENT.

And that is when the “therapy” begins. The Judge says it is wrong to think of romantic love and social duties as inevitably opposed. There is much more to an ethical life than rote obedience to society’s laws. In two letters to the young man, he argues that, although human beings are trapped in time, they can choose to develop and change.

MARRIAGE MAY LOOK LIKE A REPETITIVE DEAD END, BUT ULTIMATELY IT IS MORE SATISFACTORY THAN SHORT-LIVED PASSION, FOLLOWED BY DISILLUSION AND DESPAIR.

MARRIAGE IS THE TRANSFIGURATION OF FIRST LOVE, NOT ITS ANNIHILATION.

Marriage brings with it a commitment to the future and changes one’s conception of the eternal. This makes it an escape from the “immediate”, as well as converting two individuals into active members of a stable community.

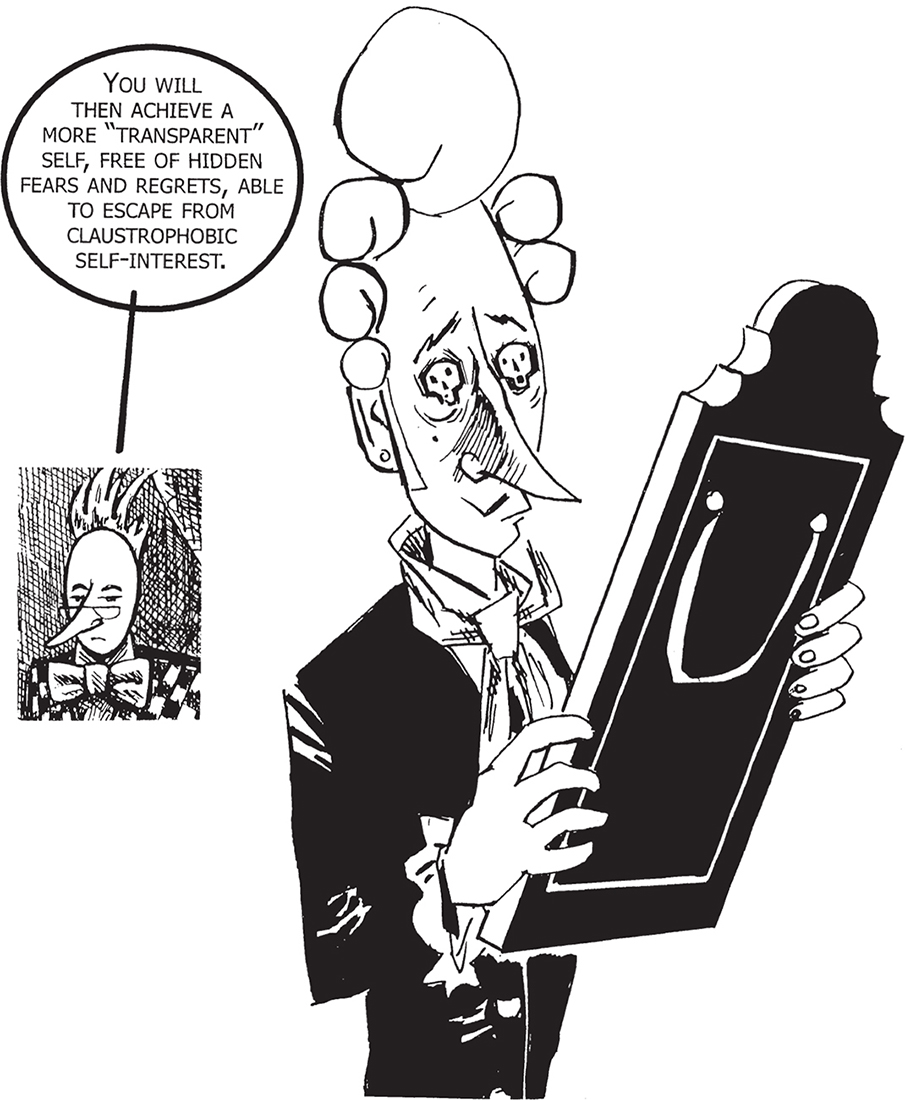

Then the Judge gives the young man some rather odd advice. He tells him to “choose despair”. By this, he means that a life devoted to disguising and escaping despair is futile. By choosing despair, the young man can face up to what causes his feelings of melancholy, recognize his guilt, repent, live by the superior categories of good and evil, and realize that life is more than just a game.

YOU WILL THEN ACHIEVE A MORE “TRANSPARENT” SELF, FREE OF HIDDEN FEARS AND REGRETS, ABLE TO ESCAPE FROM CLAUSTROPHOBIC SELF-INTEREST.

Judge Wilhelm also reassures him that the ethical life does not preclude an enjoyment of beauty and the good things in life – it is just that they are no longer the sole reason for living.

The good judge also insists that there is more to the ethical life than “crowd morality”. “Each individual must live life by choosing a set of moral principles and finding a place in the social order.” On occasion, ethical individuals may find themselves in conflict with the social norms of their community, but normally the ethical life brings contentment, because it gives meaning to the lives of those who choose it.

A “CIVIC LIFE” IS ONE OF MARRIAGE, CAREER AND SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY.

THIS LIFE MAKES NO MENTION OF “SIN” OR “FAITH” …

NEVERTHELESS, IT PREPARES ONE FOR AN EVEN HIGHER STAGE OF EXISTENCE – THE RELIGIOUS LIFE.

The ethical individual gains an overview of life, a greater sense of self, and changes his conception of time. Life is no longer merely a series of strategies to escape boredom and despair, but something related to the eternal.

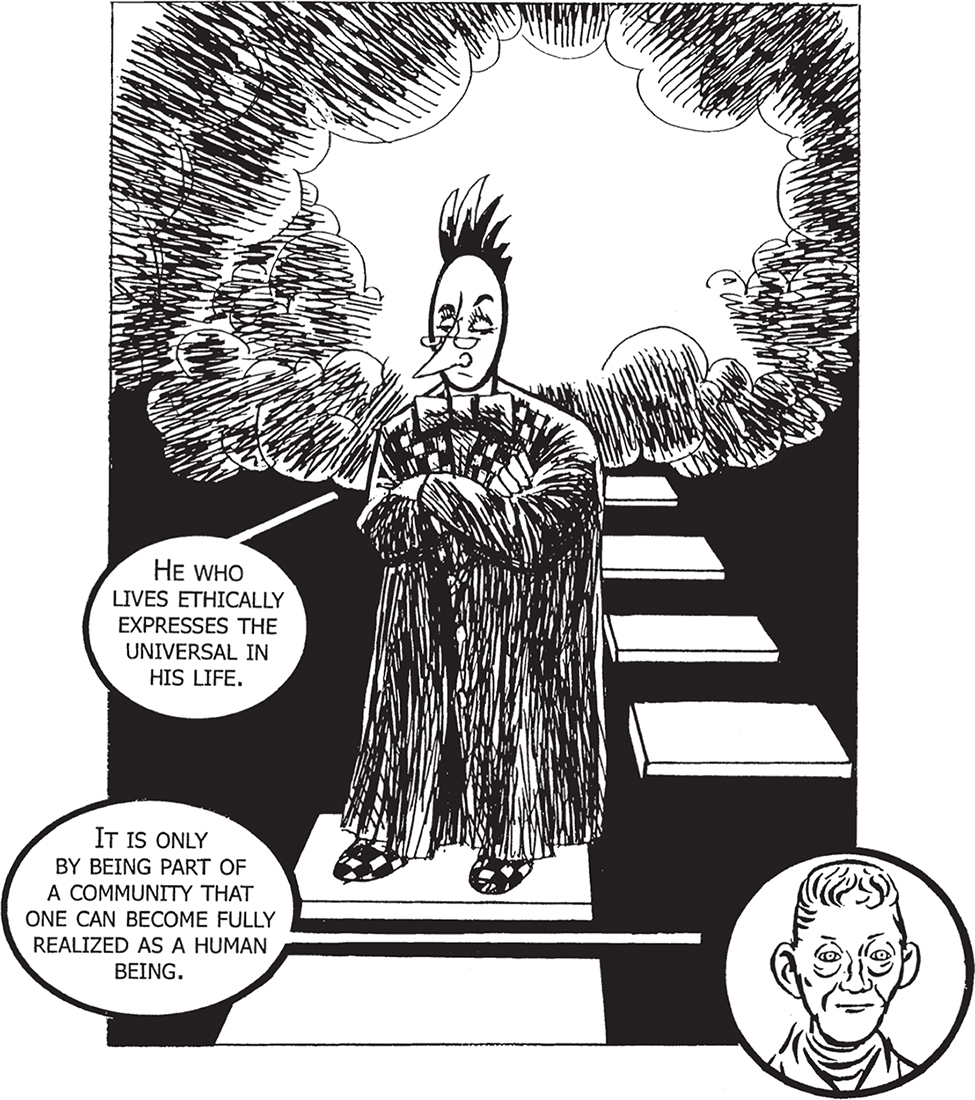

Judge Wilhelm is, frankly, a bit of a bore, especially after the dubious thrills of Johannes the Seducer. Detailed accounts of sexual depravity are more fun to read about than ethical sermons. It doesn’t help that Wilhelm is a very orthodox Protestant Lutheran, shares many of Michael Kierkegaard’s opinions and, as his Christian name would suggest, has some rather Hegelian views.

He WHO LIVES ETHICALLY EXPRESSES THE UNIVERSAL IN HIS LIFE.

IT IS ONLY BY BEING PART OF A COMMUNITY THAT ONE CAN BECOME FULLY REALIZED AS A HUMAN BEING.

The Judge’s views on married life are also exceptionally rosy. Kierkegaard seems to have been partly fantasizing here about the life he might have had with Regine.

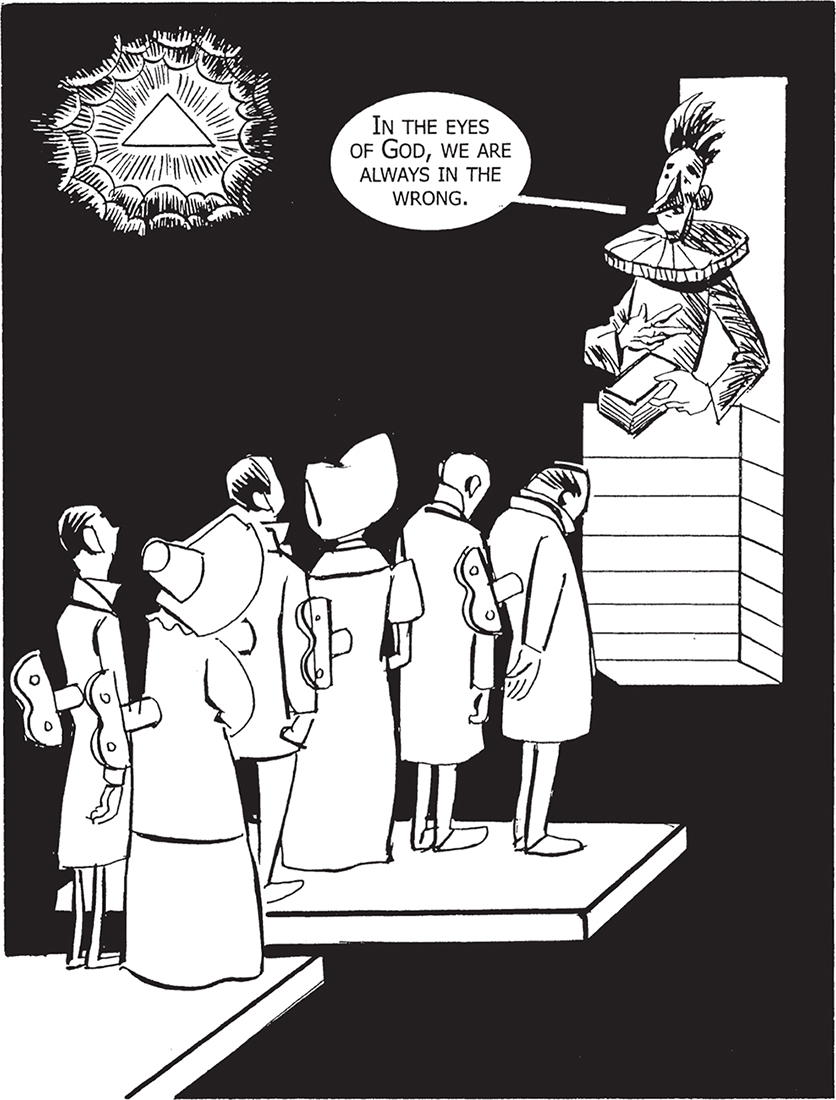

Rather disturbingly, Either/Or ends not with some final words of advice from the wise Judge, but with a religious sermon from a simple country pastor.

IN THE EYES OF GOD, WE ARE ALWAYS IN THE WRONG.

Human beings are wilful, ignorant creatures trapped in time, and Judge Wilhelm’s ethical life may be only a stepping stone to something higher and more mysterious.

Kierkegaard returned to the notion of “Stages” or “Spheres of Existence” many times. Everyone is eventually faced with alternative ways of life – like bachelorhood or marriage. And each individual has to choose one or the other, because it is not possible to have “the best of both”.

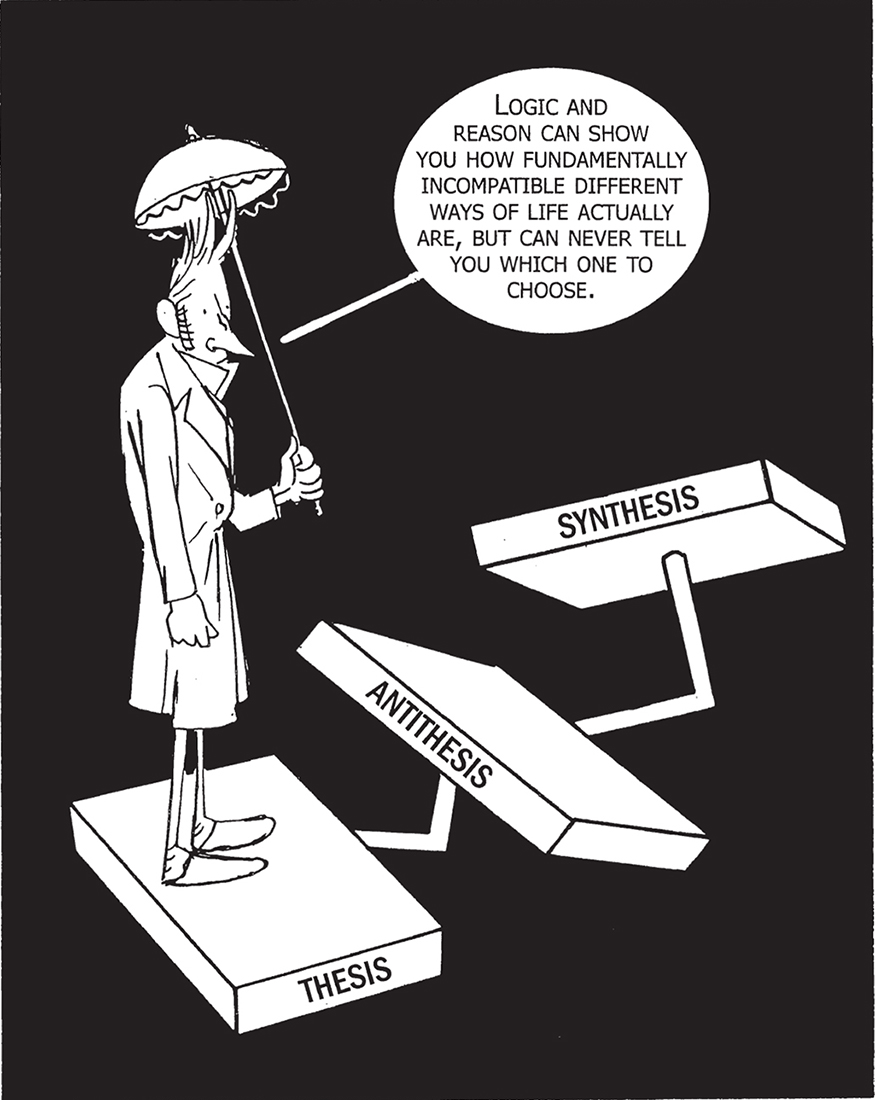

LOGIC AND REASON CAN SHOW YOU HOW FUNDAMENTALLY INCOMPATIBLE DIFFERENT WAYS OF LIFE ACTUALLY ARE, BUT CAN NEVER TELL YOU WHICH ONE TO CHOOSE.

No “stage” is more “rational” than any other, so in the end every individual’s choice is always “illogical”. Everyone has to make a dramatic “leap” to another stage – usually because they are forced to do so by overwhelming psychological feelings of inadequacy and despair.

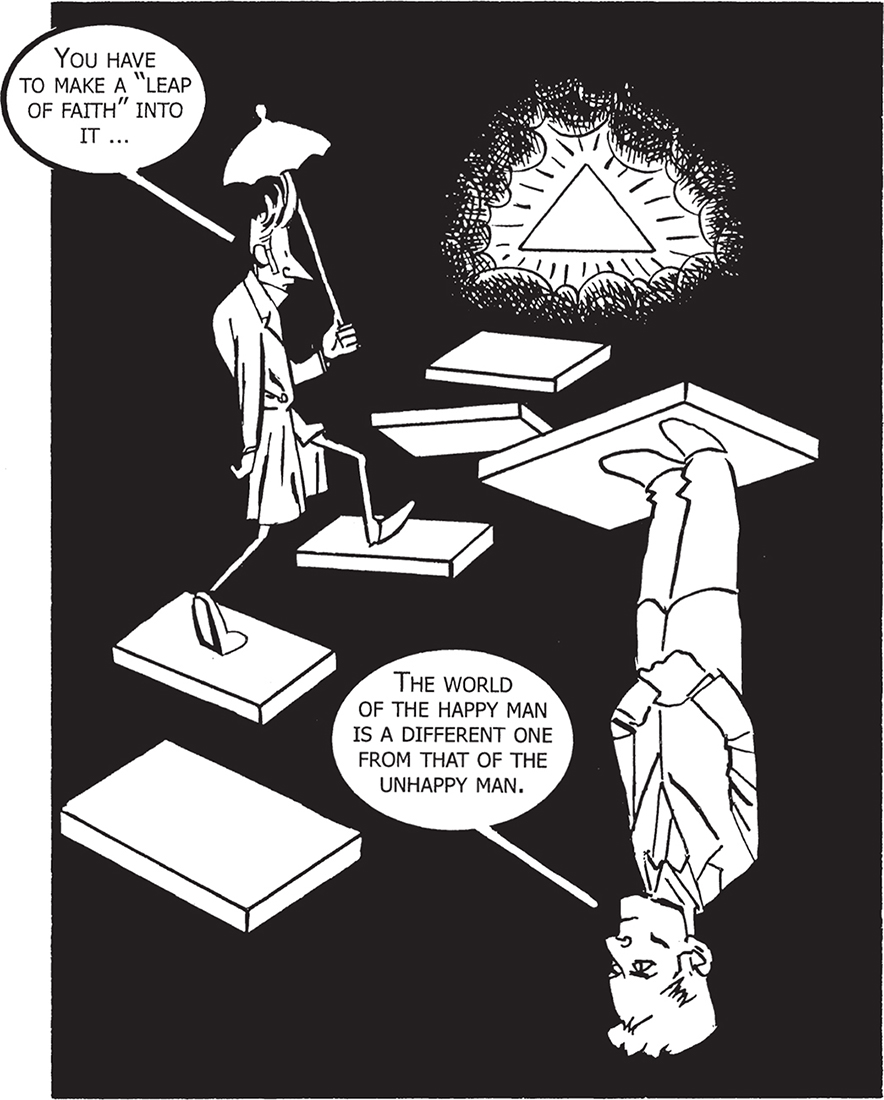

This kind of risk is especially true of the way of life that Kierkegaard aspired to – the religious world-view. The modern and deeply ascetic philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) agreed. Religion is a “form of life” in which the concepts and practices contained make sense only from “inside”. No one can truly describe it for you.

YOU HAVE TO MAKE A “LEAP OF FAITH” INTO IT …

THE WORLD OF THE HAPPY MAN IS A DIFFERENT ONE FROM THAT OF THE UNHAPPY MAN.

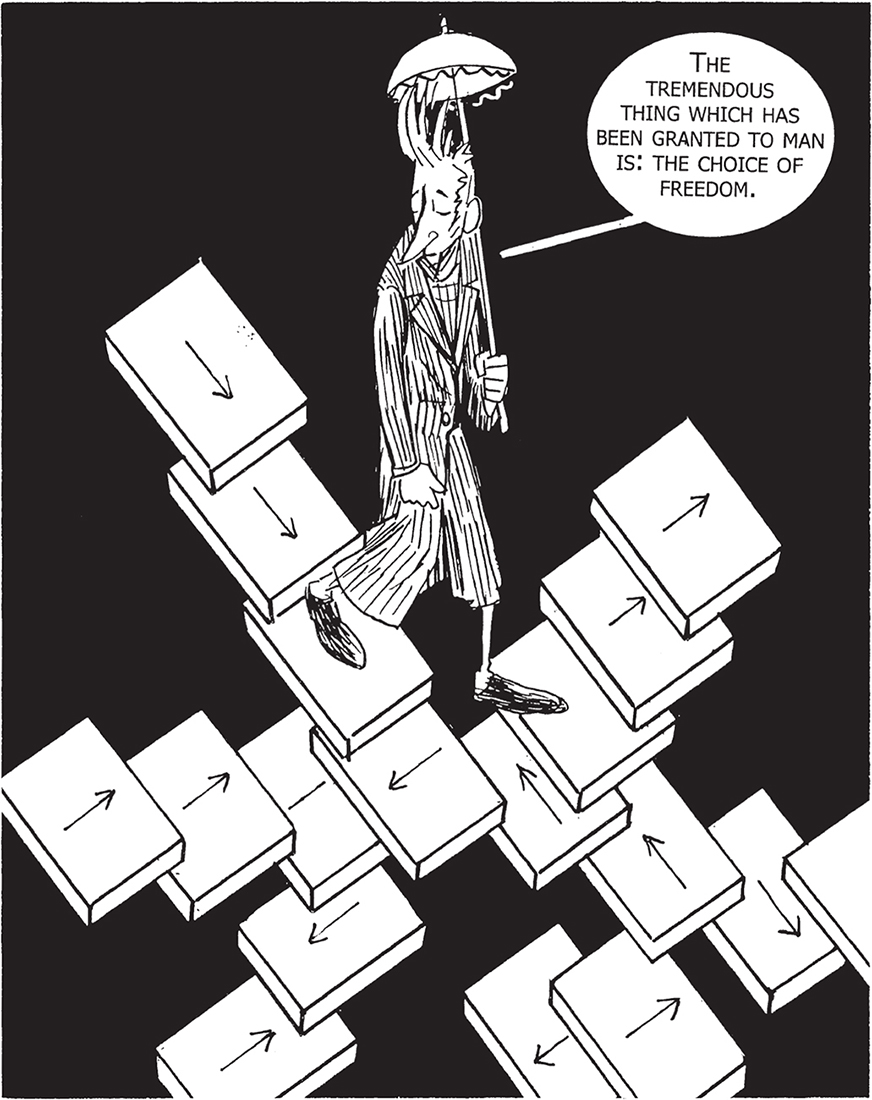

For Hegel, human freedom is a derivative and collective idea – a concept that makes sense only within the ideals of the community. For Kierkegaard, “freedom” is a more absolute and mysterious human attribute that has meaning only when an individual refuses to submit to group approval.

THE TREMENDOUS THING WHICH HAS BEEN GRANTED TO MAN IS: THE CHOICE OF FREEDOM.

It is exercising this freedom by choosing that makes you a true individual. “In making a choice it is not so much a question of choosing the right, as of the energy, the earnestness and the pathos with which one chooses.” What you choose is less important finally than how you choose. This is why Kierkegaard often presents his readers with highly persuasive exponents of wholly different sets of values, and leaves it up to each individual reader to decide.

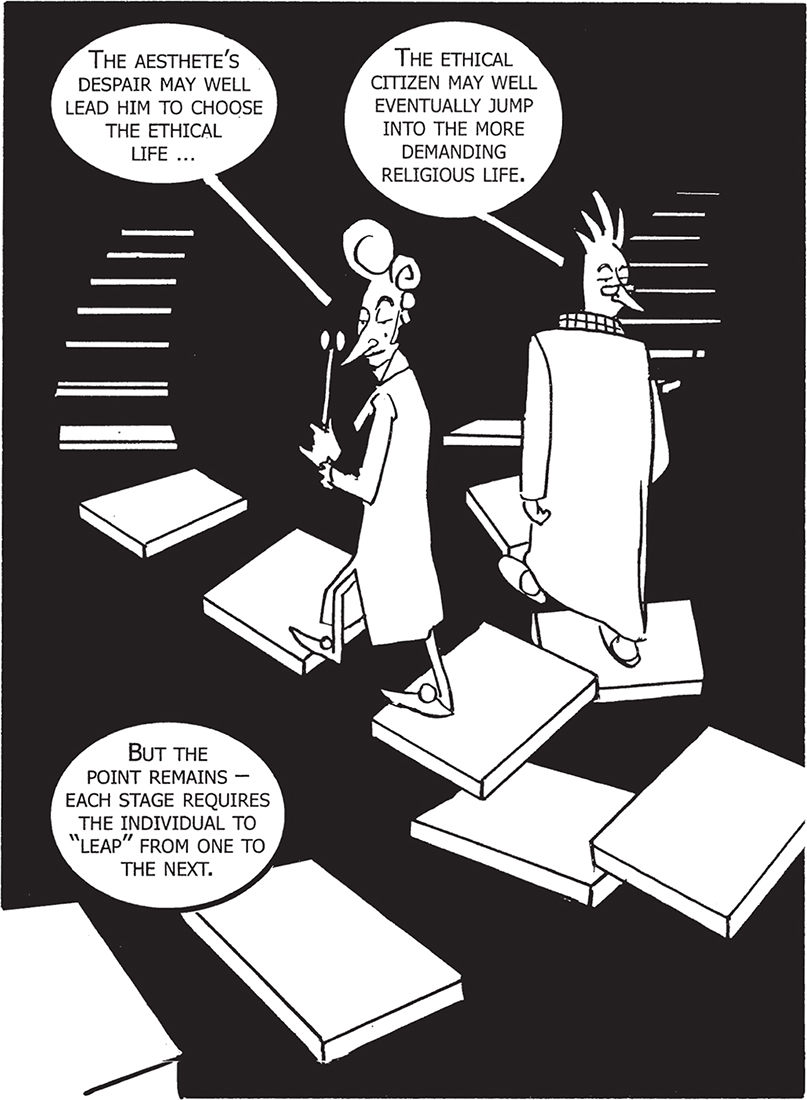

THE ETHICAL CITIZEN MAY WELL EVENTUALLY JUMP INTO THE MORE DEMANDING RELIGIOUS LIFE.

THE AESTHETE’S DESPAIR MAY WELL LEAD HIM TO CHOOSE THE ETHICAL LIFE …

BUT THE POINT REMAINS – EACH STAGE REQUIRES THE INDIVIDUAL TO “LEAP” FROM ONE TO THE NEXT.

There is no “Hegelian logic” of the inevitable about the climb upwards to “Absolute Truth”.

After the success of Either/Or, Kierkegaard produced a series of pseudonymous books at a phenomenal rate; although, by this time, most of Copenhagen’s intelligentsia knew well enough who had written them.

FEAR AND TREMBLING, Johannes de Silentio, 1843

REPETITION, Constantin Constantius, 1843

PHILOSOPHICAL FRAGMENTS, Johannes Climacus, 1844

THE CONCEPT OF DREAD, Vigilus Haufniensis, 1844

Stages ON LIFE’S WAY, Hilarius Bookbinder, 1845

CONCLUDING UNSCIENTIFIC POSTSCRIPT, Johannes Climacus, 1846

He also produced more orthodox signed works on religious themes, often published simultaneously with the more challenging works listed above: Upbuilding Discourses (1843–4), Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions (1845), Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits (1847), Christian Discourses (1848), The Lily of the Field, The Bird of the Air (1849).

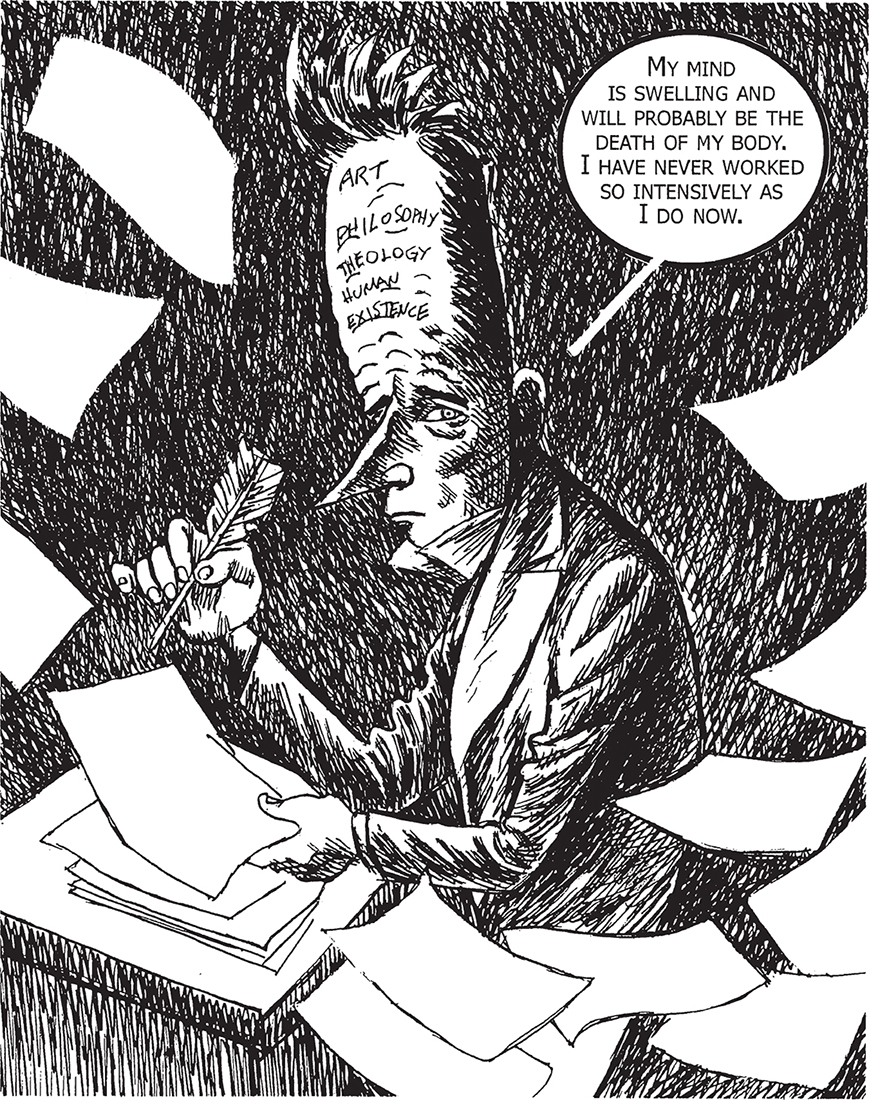

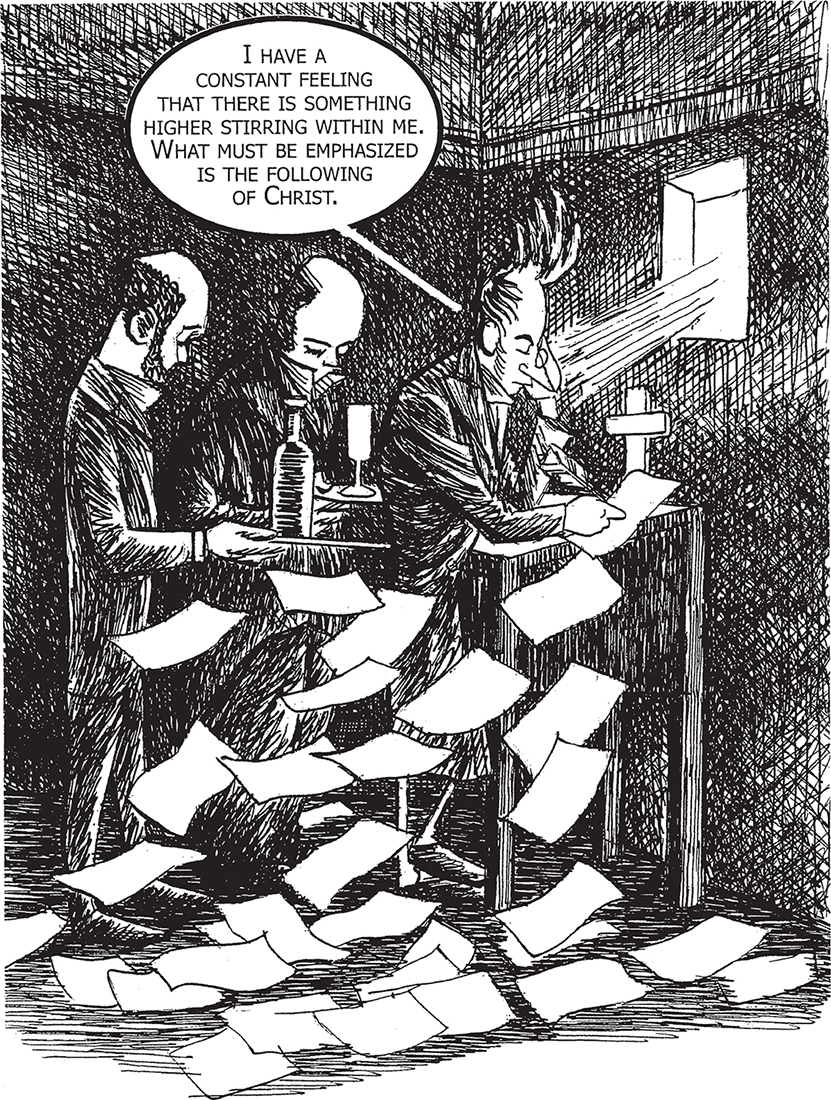

Kierkegaard’s extraordinarily prolific output can be partly explained by his belief that he was condemned to die young. An equally convincing explanation for his incessant production line is that he was an obsessive thinker, determined to publish his ideas about virtually everything – philosophy, art, theology, human existence, and, perhaps most importantly of all, what it actually means to “become a Christian”. It’s an extraordinary record for someone who was physically rather frail.

MY MIND IS SWELLING AND WILL PROBABLY BE THE DEATH OF MY BODY. I HAVE NEVER WORKED SO INTENSIVELY AS I DO NOW.

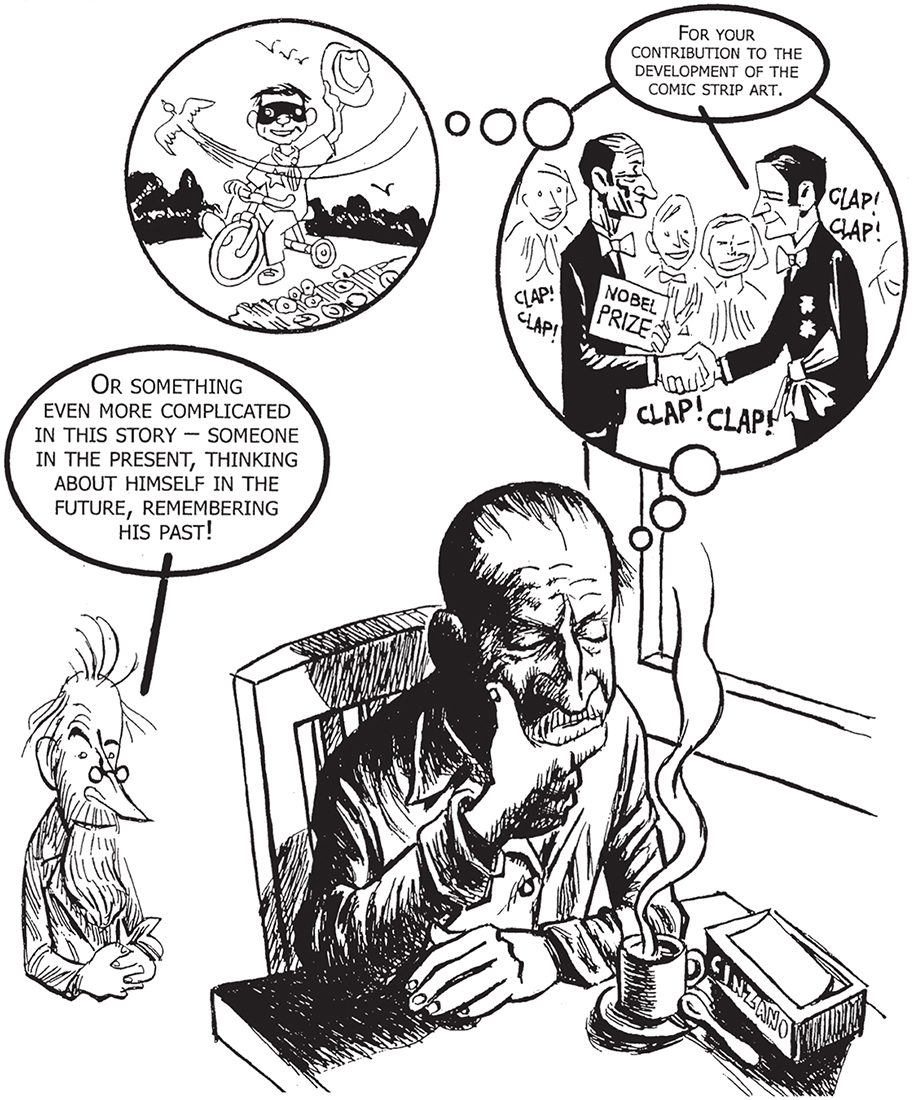

Repetition develops an idea taken from the earlier Either/Or. It is impossible to classify either as philosophy or psychology but is a complicated mixture of both. Its fictional author is Constantin Constantius, a shrewd intellectual, who tells us all about a young man in love. A day or two after he gets engaged, an odd thought strikes him. He imagines his future, not as a happily married young husband but as a disillusioned old man, sunk in an armchair, remembering the love of his youth.

SO HE PANICS.

THE GIRL I LOVE IS THE MUSE WHO TURNED ME INTO A POET, BUT I’VE SEEN WHERE MARRYING HER MIGHT LEAD.

“She had made him a poet, and in so doing, she had signed her own death warrant …”

The indecisive young poet breaks off the engagement. Constantius advises him to pretend to have a mistress. His outraged fiancée will go along with his plans – by rejecting him. He doesn’t have the nerve to go that far, but, a few days later, wonders if he has made the wrong decision after all, and becomes an unhappy rememberer of “what might have been”.

So, SHOULD HE START ALL OVER AGAIN?

I LONG FOR SOMEONE TO TELL ME WHAT TO DO!

ANYTHING RATHER THAN MAKE A CHOICE.

But then he reads in the paper that she has married someone else, so “repetition” is not possible. He commits suicide. Well, he does in the first version. By this time, Kierkegaard knew of Regine’s engagement to another man, so he changed the ending. The young man now celebrates his independence as a writer.

Repetition is a curious tale of self-imposed misery, partly autobiographical and partly therapeutic. But it does explore further the idea of the self-deceived individual who drifts through life dreaming of an imaginary past and future.

FOR YOUR CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMIC STRIP ART.

OR SOMETHING EVEN MORE COMPLICATED IN THIS STORY – SOMEONE IN THE PRESENT, THINKING ABOUT HIMSELF IN THE FUTURE, REMEMBERING HIS PAST!

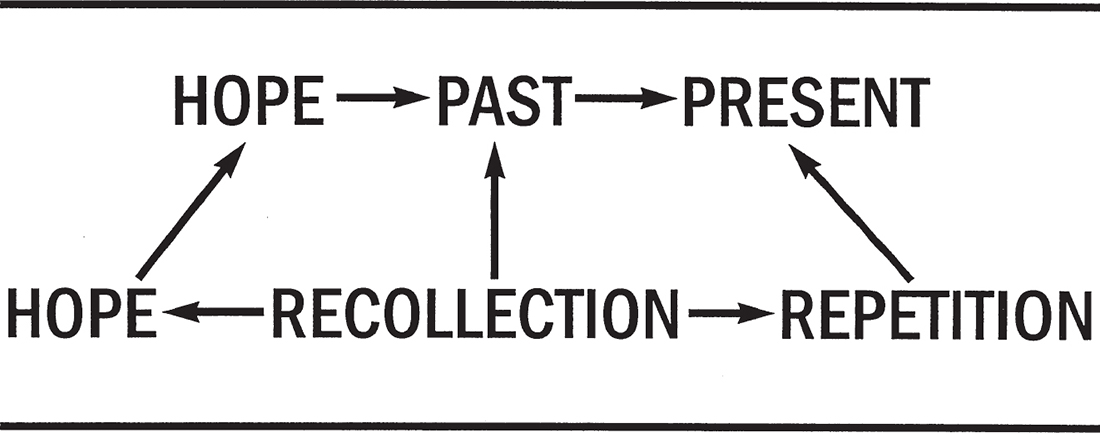

It’s easy to be nostalgic and believe that things were always better in the past. Or to hope that the future will be better than now. Both are common strategies that people use to avoid being “present to themselves”. They end up indecisive, in a constant state of unspecific melancholy and regret.

So “repetition” can be a good thing – if it means a second chance to choose something you repent having lost. Repetition also reinforces the idea that it is best to live in the present, not in some imaginary elsewhere. And the “repetition” of marriage is one way of freeing yourself from imaginary hopes or sad regrets.

HOPE IS A CHARMING MAIDEN WHO SLIPS THROUGH THE FINGERS.

RECOLLECTION IS A BEAUTIFUL OLD WOMAN, BUT OF NO USE AT THE INSTANT.

REPETITION IS A BELOVED WIFE OF WHOM ONE NEVER TIRES.

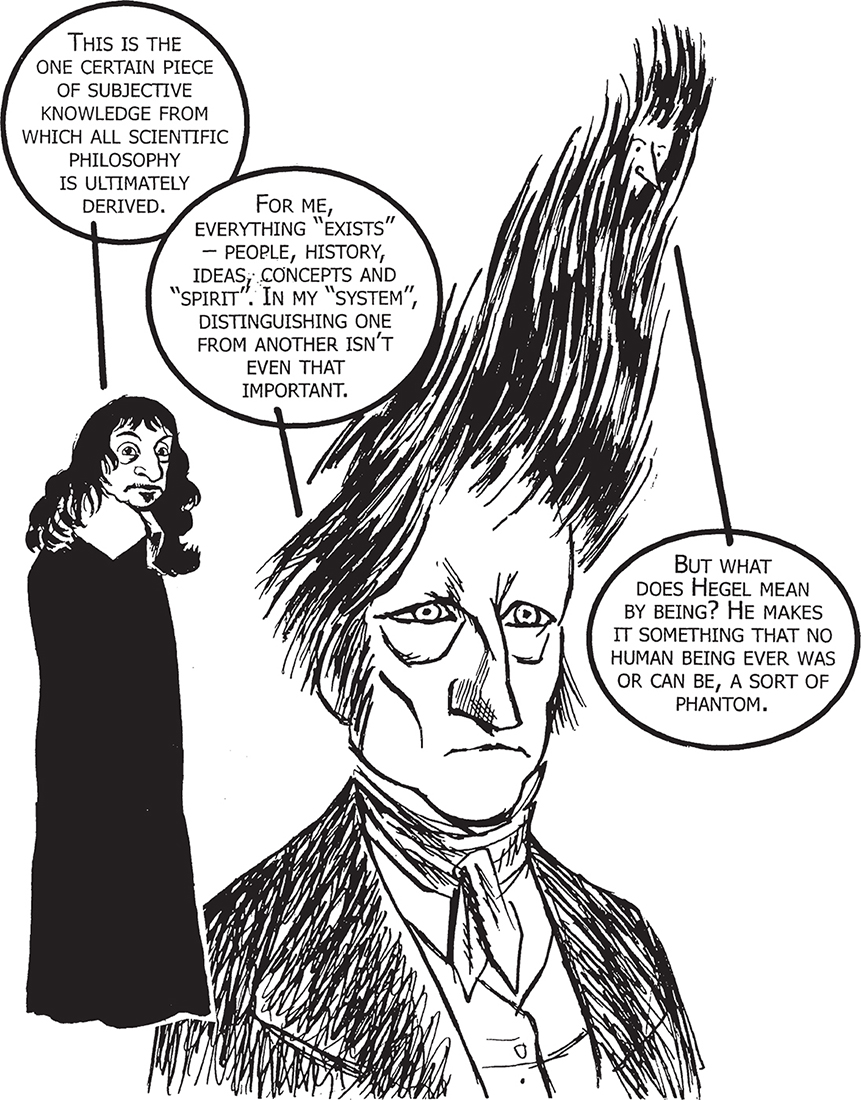

Kierkegaard claims that, until he finally decides what to do, the young poet does not really “exist”. What does he mean? Clearly there’s more to “existence” than just breathing, eating and thinking. The French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) was convinced he had proved that every thinking individual has to exist (“I think therefore I am”).

THIS IS THE ONE CERTAIN PIECE OF SUBJECTIVE KNOWLEDGE FROM WHICH ALL SCIENTIFIC PHILOSOPHY IS ULTIMATELY DERIVED.

FOR ME, EVERYTHING “EXISTS” – PEOPLE, HISTORY, IDEAS, CONCEPTS AND “SPIRIT”. IN MY “SYSTEM”, DISTINGUISHING ONE FROM ANOTHER ISN’T EVEN THAT IMPORTANT.

BUT WHAT DOES HEGEL MEAN BY BEING? HE MAKES IT SOMETHING THAT NO HUMAN BEING EVER WAS OR CAN BE, A SORT OF PHANTOM.

Kierkegaard insisted that philosophical concepts and individual human beings “exist” in wholly different ways. The living, striving suffering self determines one’s existence, not some remote abstract ego that is aware only of its thoughts.

FOR AN ABSTRACT THINKER TO TRY TO PROVE HIS EXISTENCE BY THE FACT THAT HE THINKS IS A CURIOUS CONTRADICTION.

THIS PURE EGO CANNOT WELL HAVE ANYTHING OTHER THAN A PURELY CONCEPTUAL EXISTENCE.

Kierkegaard’s point is a fairly elementary one. Concepts and reason can only ever tell us about the possibilities of existence, not about its actuality. A mathematician can happily use reason and concepts to tell us all about the possible areas and circumferences of a circular pond in the park. What he can’t do is use reason to tell us whether or not such a pond actually exists.

“Existence” is much more than just something you are born with. It is something you have to strive for, usually by distinguishing yourself from “the crowd”, which may be biologically alive but doesn’t “exist”. This means that Kierkegaard’s individuals are often asocial, or even anti-social, beings, at odds with those who surround them. Only by recognizing their true situation – knowing they are free to choose and consequently responsible for their choices – do they truly “exist” (or as later “existentialist” philosophers would say, do they become “authentic”).

SHOULD I BE A LONELY BACHELOR, A CAREFREE AESTHETE OR A CONVIVIAL HUSBAND AND FATHER?

THAT CHOICE IS HARD BECAUSE “REASON” CANNOT TELL YOU HOW TO LIVE YOUR LIFE.

ONLY YOU CAN MAKE THAT FIRST INITIAL “LEAP”. WITH NO ONE TO HELP YOU.

AND THE ISSUE IS AN URGENT ONE – BECAUSE HUMAN BEINGS HAVE SHORT LIVES.

This freedom to choose who you are, as well as what you do, sounds superficially rather attractive. But once you have made your decision, only you can be held responsible for it, if things go horribly wrong.

THE “GUILT” OF BEING RESPONSIBLE IF THINGS GO WRONG.

THIS IS WHY I STRESS THE “DREAD” OF ALL THOSE CHOICES AND POSSIBILITIES …

EACH INDIVIDUAL MUST MAKE DECISIONS BASED ON PERSONAL DESIRES, HOPES, FEARS AND LONGINGS.

THE “DESPAIR” OF HAVING TO MAKE DECISIONS WITHOUT EXTERNAL HELP …

The choice of a way of life can be made only by the person who has to live it – which is what Kierkegaard means by his puzzling and famous phrase: “Truth is Subjectivity.”

Kierkegaard himself had chosen a rather eccentric way of life. His days were remarkably uneventful. He rarely left Copenhagen; his whole life was one of writing, attending the theatre and taking brief journeys into the surrounding countryside.

ON ONE OCCASION, I VISITED THE FARM WHERE MY FATHER HAD WORKED AS A SHEPHERD BOY.

He greatly enjoyed walking the streets of the city, a hunched figure in black, carrying his umbrella, talking to ordinary people, whose conversation he valued highly. Like most good Danes, he attended the State Lutheran church regularly, and now thought of himself as a “religious poet”.

All of Kierkegaard’s writings are, in one way or another, deeply concerned with the religious way of life. And, unsurprisingly, he disagreed violently with Hegel’s analysis of religion and religious belief. Which takes us to his most important philosophical preoccupation – the relationship between religious faith and reason, a subject he wrote about extensively but again, pseudonymously, in his more “philosophical” works.

PHILOSOPHICAL FRAGMENTS and CONCLUDING UNSCIENTIFIC POSTSCRIPT TO PHILOSOPHICAL FRAGMENTS, WRITTEN BY ME, “JOHANNES CLIMACUS”.

Everyone has beliefs, from the everyday to the religious. Most of our beliefs are based on habit, some on reason and evidence, and rather a lot on faith.

I BELIEVE THAT MY DOOR KEY WILL WORK, BECAUSE IT HABITUALLY DOES.

I BELIEVE THAT THE EARTH IS ROUND, BECAUSE I HAVE SEEN PICTURES OF IT.

I PERSONALLY HAVE FAITH IN THE METAPHYSICAL ASSERTION THAT EVERY EVENT HAS A CAUSE AND THAT TIME ALWAYS GOES FORWARD.

BUT THERE IS MORE OBJECTIVE UNCERTAINTY TO OUR MODERN SCIENTIFIC BELIEFS THAN MOST OF US REALIZE.

For a belief to be “rational”, some kind of proof or valid argument is usually presupposed. A belief based on faith, however, has more to do with a personal commitment, and usually appeals to some kind of transcendent authority.

NO. OUR BELIEFS HAVE MORE TO DO WITH AN ACCEPTANCE OF DIVINE AUTHORITY AND AN EXERCISE OF OUR OWN PERSONAL WILLPOWER.

OUR RELIGIOUS BELIEFS ARE AS DEMONSTRABLE AS ANY OF OUR OTHER BELIEFS.

Some philosophers and theologians suggest that reason and faith together can form solid foundations for religious belief. Others insist that the two are inherently incompatible.

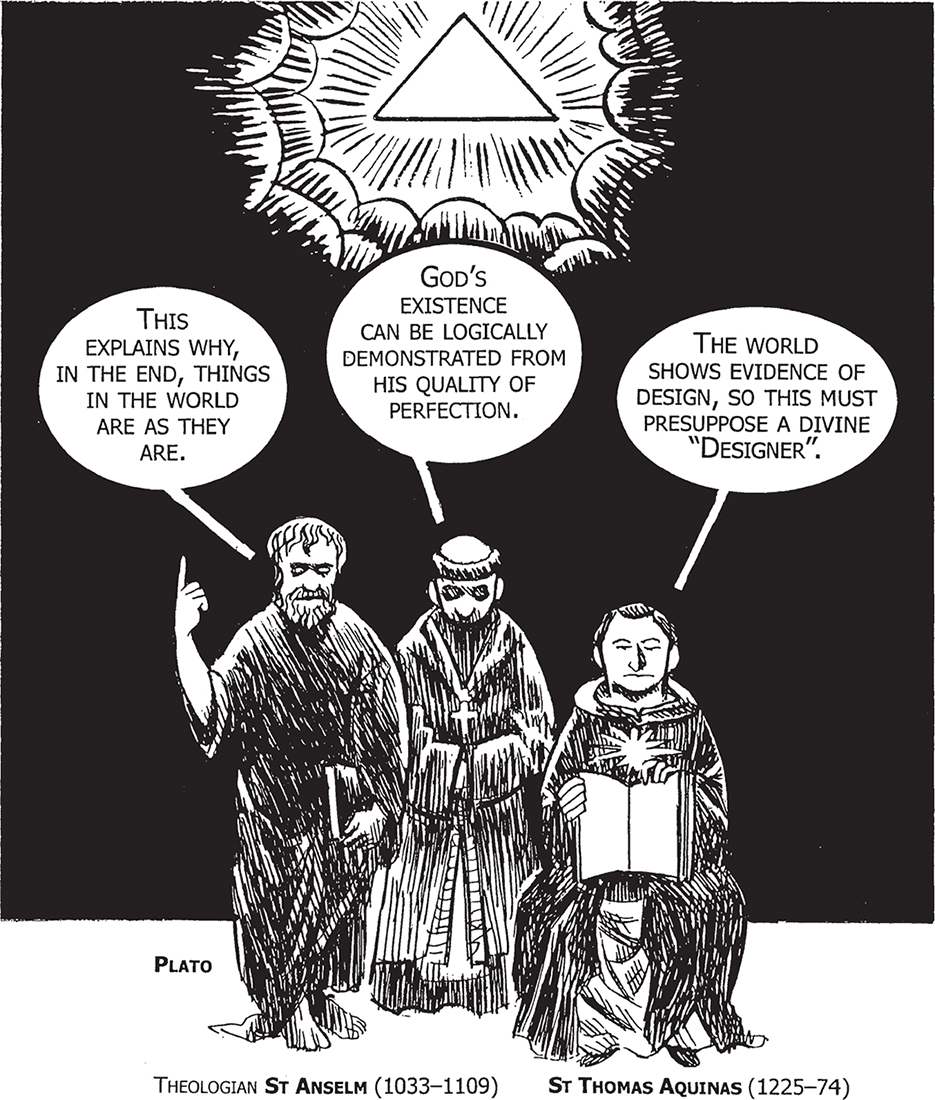

Those “apologetic” theologians who insist that reason and faith can be reconciled are sometimes called “natural theologians” or “compatibilists”. They often argue that God’s existence can be proved with reason. “Natural Theology” goes back at least as far as Plato (427–347 BC) and Aristotle (384–322 BC), who both appealed to transcendent entities like “The Good” and “The Unmoved Mover”.

GOD’S EXISTENCE CAN BE LOGICALLY DEMONSTRATED FROM HIS QUALITY OF PERFECTION.

THIS EXPLAINS WHY, IN THE END, THINGS IN THE WORLD ARE AS THEY ARE.

THE WORLD SHOWS EVIDENCE OF DESIGN, SO THIS MUST PRESUPPOSE A DIVINE “DESIGNER”.

Rationalist philosophers – Descartes, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) and others – also provided more elaborate versions of such “proofs”.

Hegel’s approach to this conflict between reason and faith was, essentially and typically, to dissolve it. For Hegel, God is not a transcendent being, but “immanent” – a part of all human beings and their spiritual selves. Indeed, God is identical with “Absolute Reality” – all that exists.

THERE IS ONLY ONE BEING … AND THINGS BY THEIR VERY NATURE FORM PART OF IT, AND THERE IS IN THE BELIEVER A DIVINE ELEMENT WHICH REDISCOVERS ITSELF, ITS TRUE NATURE.

The mystery of the Incarnation – God becoming human in the form of Christ – is no more than an allegorical fable which tells us that divine and human natures are not radically or intrinsically different.

Religion merely hints through myths and symbols at fundamental truths, truths that philosophy ultimately reveals more clearly. Religion is imaginative and figurative; philosophy is rational and conceptual. Some theologians welcomed Hegel’s “apologetic” explanation of the relevance and value of religion and agreed that it was a positive force for good.

RELIGIOUS BELIEFS REINFORCE THE UNDERLYING MORAL PRINCIPLES OF SOCIETY AND HELP BIND COMMUNITIES TOGETHER.

BUT PERHAPS THE COST OF HEGEL’S “MEDIATION” BETWEEN RELIGION AND PHILOSOPHY IS TOO HIGH …

HEGEL HAS DISSOLVED CHRISTIAN DOCTRINE INTO VAGUE PHILOSOPHICAL MUSH.

One obvious problem for “compatibilists” is that Christianity’s doctrines seem utterly beyond rational justification – God created the world from nothing; He is both one and three persons; and, as an infinite being, He took on a brief historical and finite existence in human form. Clever theologians can try to explain away these paradoxes. But a more radical way of dealing with them is to celebrate their very absurdity. After all, if God’s existence could be proved, and Christian doctrine made logically demonstrable, then there would be no real need for faith in the first place.

CREDO QUIA ABSURDUM EST – I BELIEVE BECAUSE IT IS ABSURD.

THE THEOLOGIAN TERTULLIAN (155–225 AD) MADE THIS POINT VERY EARLY ON …

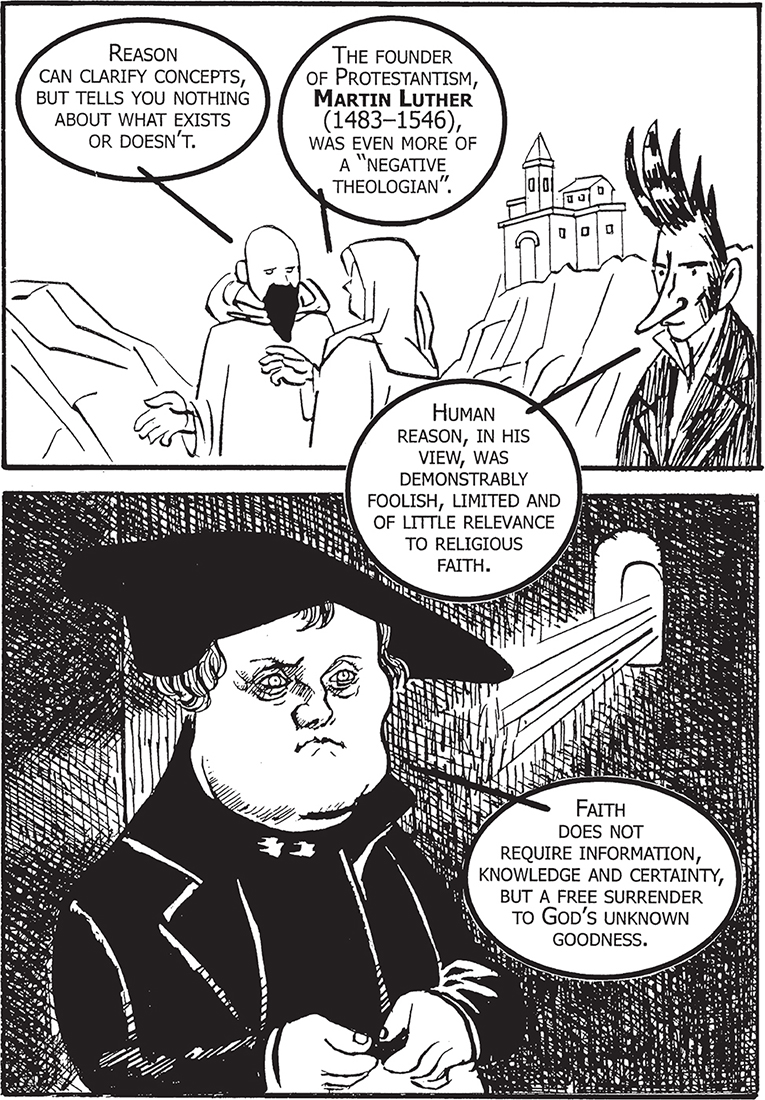

The Franciscan philosophers John Duns Scotus (1266–1308) and William of Ockham (1285–1349) were critical of all philosophical attempts to prove God’s existence.

The FOUNDER of Protestantism, MARTIN LUTHER (1483–1546), WAS EVEN MORE OF A “NEGATIVE THEOLOGIAN”.

REASON CAN CLARIFY CONCEPTS, BUT TELLS YOU NOTHING ABOUT WHAT EXISTS OR DOESN’T.

HUMAN REASON, IN HIS VIEW, WAS DEMONSTRABLY FOOLISH, LIMITED AND OF LITTLE RELEVANCE TO RELIGIOUS FAITH.

FAITH DOES NOT REQUIRE INFORMATION, KNOWLEDGE AND CERTAINTY, BUT A FREE SURRENDER TO GOD’S UNKNOWN GOODNESS.

French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal (1623–62) agreed that reason alone could not settle any matter of religious belief. He proposed a famous “wager”. Belief in God is a better bet, because if you are wrong, the consequences are unknown to you; if you are right, heaven awaits.

At THE FAR END OF AN INFINITE DISTANCE, A COIN IS BEING SPUN. HOW WILL YOU WAGER?

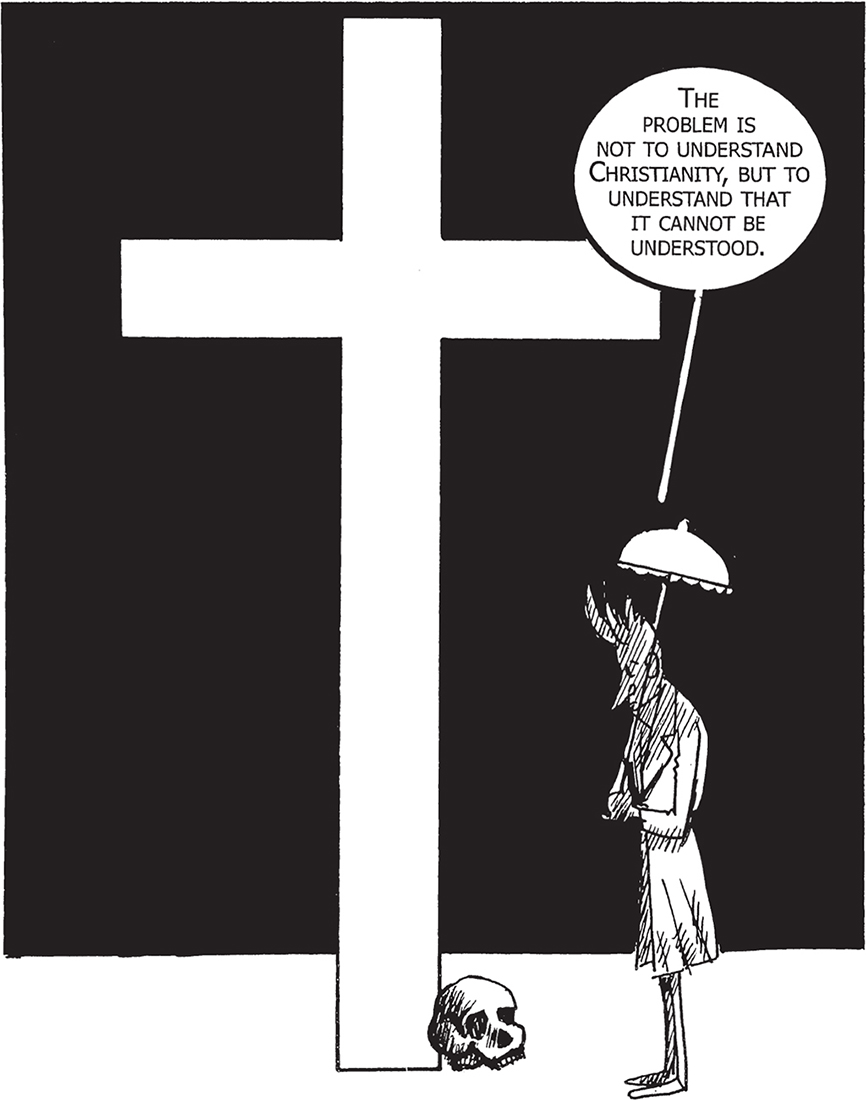

Kierkegaard read and admired Tertullian, Luther and Pascal, as well as other, more contemporary theologians like Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that religion was its own “sphere of existence” which had nothing to do with reason. And Kierkegaard is himself probably the most radical and uncompromising incompatibilist of all time.

THE PROBLEM IS NOT TO UNDERSTAND CHRISTIANITY, BUT TO UNDERSTAND THAT IT CANNOT BE UNDERSTOOD.

Kierkegaard frequently insisted that his philosophy was always centred on one deceptively simple question. “What is it to become a Christian?”

For most people, becoming a Christian is mostly a matter of being born to Christian parents, observing certain religious rituals and getting warm feelings of solidarity and worthiness from church attendance. This was especially true of the Protestant Lutheran churchgoers in Denmark, who, as Danish citizens, were also required to be members of the State Church.

“Thus it was established by the State as a kind of eternal principle that every child is naturally born a Christian. The State delivers generation after generation, an assortment of Christians, each bearing the manufacturer’s trademark of the State, with perfect accuracy, one Christian exactly like all the others with the greatest possible uniformity of a factory product.”

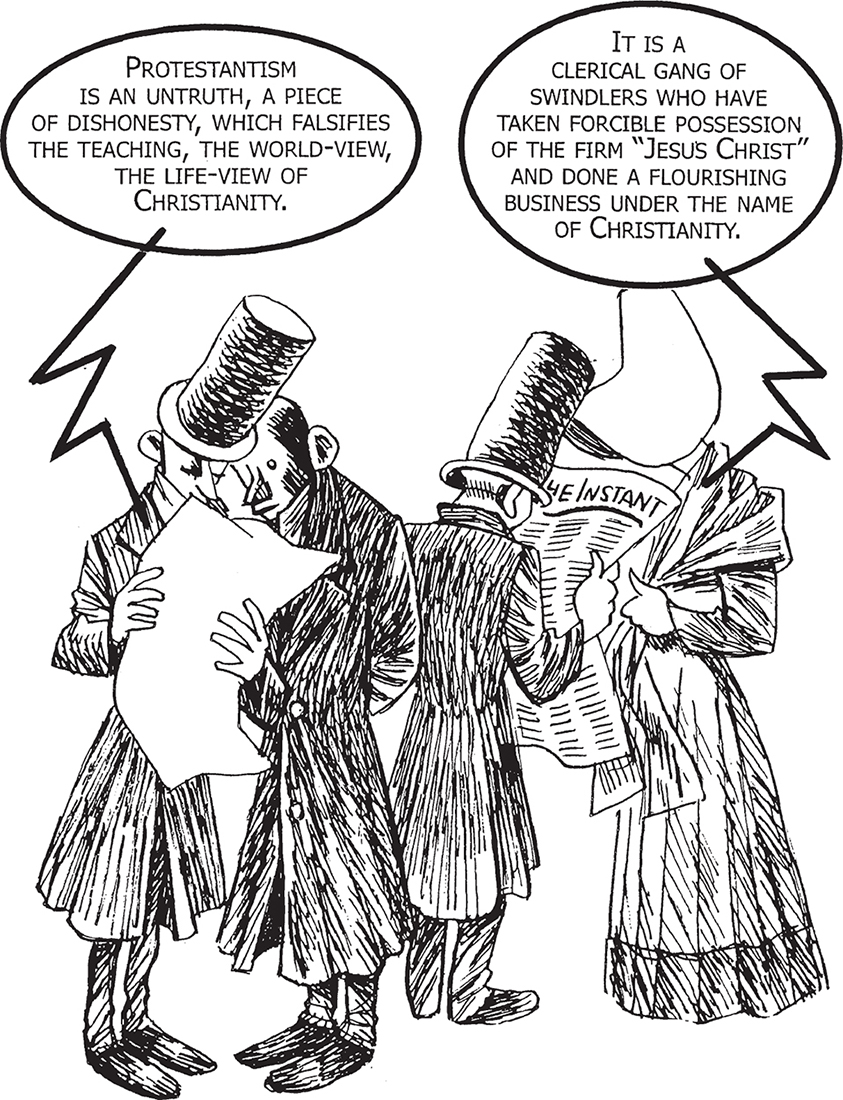

Kierkegaard attacked what he called “Christendom”. This included the majority of churchgoers in a secular and scientific age who declared that Christianity was a rational and sensible religion, based on true doctrines that Hegel had proven were the logical consequences of Western philosophical thought.

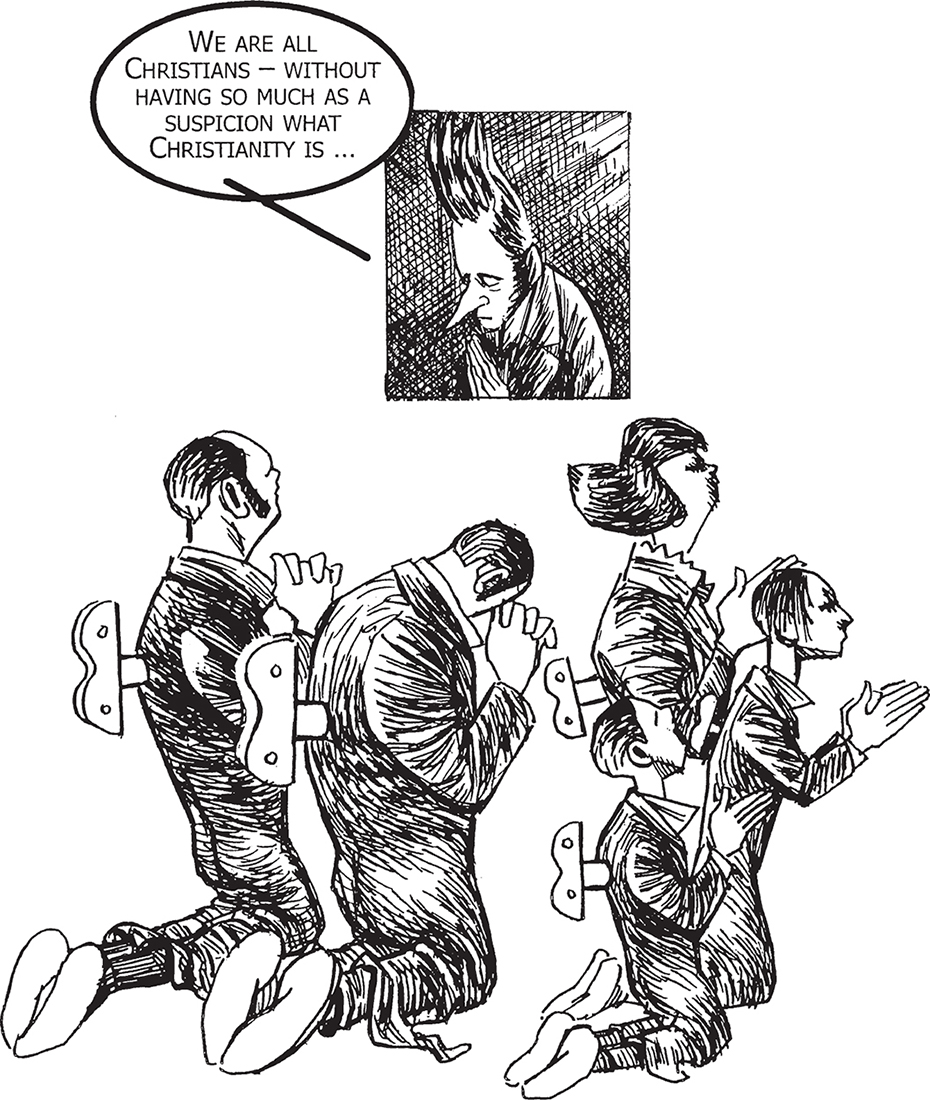

But, for Kierkegaard, becoming a Christian was a mysterious and agonizing process. No one really knew what it actually meant.

WE ARE ALL CHRISTIANS – WITHOUT HAVING SO MUCH AS A SUSPICION WHAT CHRISTIANITY IS …

Kierkegaard’s Christianity is very different to this “Sunday Christianity”. Every Christian is by definition an individual – so membership of some particular religious institution means very little. A true Christian is rarely happy or complacent. Kierkegaard’s Christianity was like that of his father – a religion of guilt, anxiety and suffering. Christianity had to be a total way of life, which meant that it was impossible to be both a true Christian and a successful member of society. So absolute were its demands that the true Christian must necessarily be an “outsider”.

BACK TO THE MONASTERY OUT OF WHICH LUTHER BROKE – THAT IS THE TRUTH.

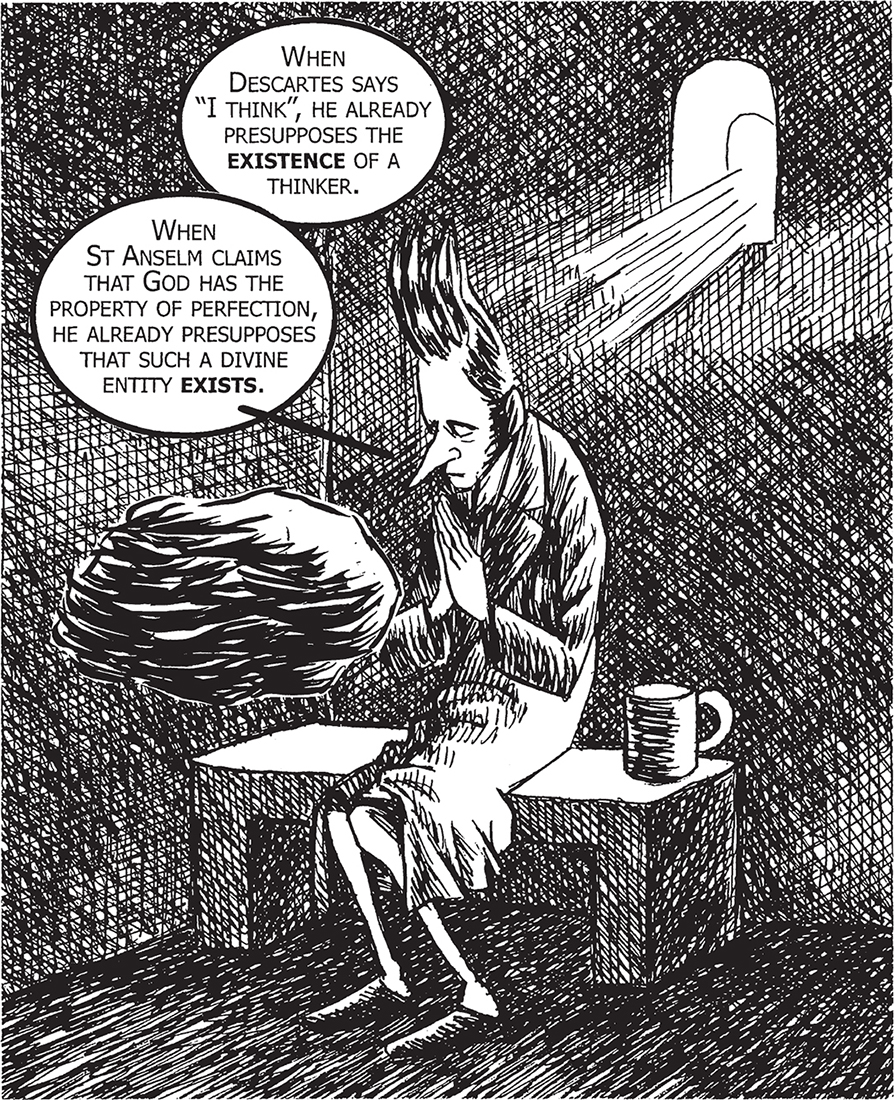

“Attempts to prove God’s existence are an excellent subject for a comedy of the highest lunacy.” Kierkegaard makes the point time and again that it is impossible ever to prove that anything exists.

WHEN DESCARTES SAYS “I THINK”, HE ALREADY PRESUPPOSES THE EXISTENCE OF A THINKER.

WHEN ST ANSELM CLAIMS THAT GOD HAS THE PROPERTY OF PERFECTION, HE ALREADY PRESUPPOSES THAT SUCH A DIVINE ENTITY EXISTS.

“The entire demonstration always becomes an additional development of the consequences that flow from my having assumed that the object in question already exists. Thus I always reason from existence, not toward existence. I do not, for example, prove that a stone exists, but that some already existing thing is a stone.”

Kierkegaard’s criticism of the “ontological” argument is that you cannot drag the existence of anything out of definitions or some ingenious logic. However hard you try, God’s existence cannot be proved like some kind of mathematical theorem. This is especially true for we finite beings whose intellects are exceedingly limited.

HOW CAN WE HOPE TO UNDERSTAND THE “EXISTENCE” OF A BEING WHO IS ETERNAL?

A criticism that is often made about Kierkegaard is that he claims to despise philosophical method, is dismissive of reason, and yet uses both brilliantly in his attack on orthodox Christian “proofs” for God’s existence. But Kierkegaard never says that being a Christian and using reason are incompatible, just that reason cannot make you into a believer. And, like Hegel, Kierkegaard rather celebrated the fact that it was a constant trait of rational thought to throw up irreconcilable paradoxes.

THE THINKER WITHOUT PARADOX IS LIKE A LOVER WITHOUT FEELINGS. THE SUPREME PARADOX OF ALL THOUGHT IS THE ATTEMPT TO DISCOVER SOMETHING THAT THOUGHT CANNOT THINK.

But, unlike Hegel, he never thought religious paradoxes could be “mediated”.

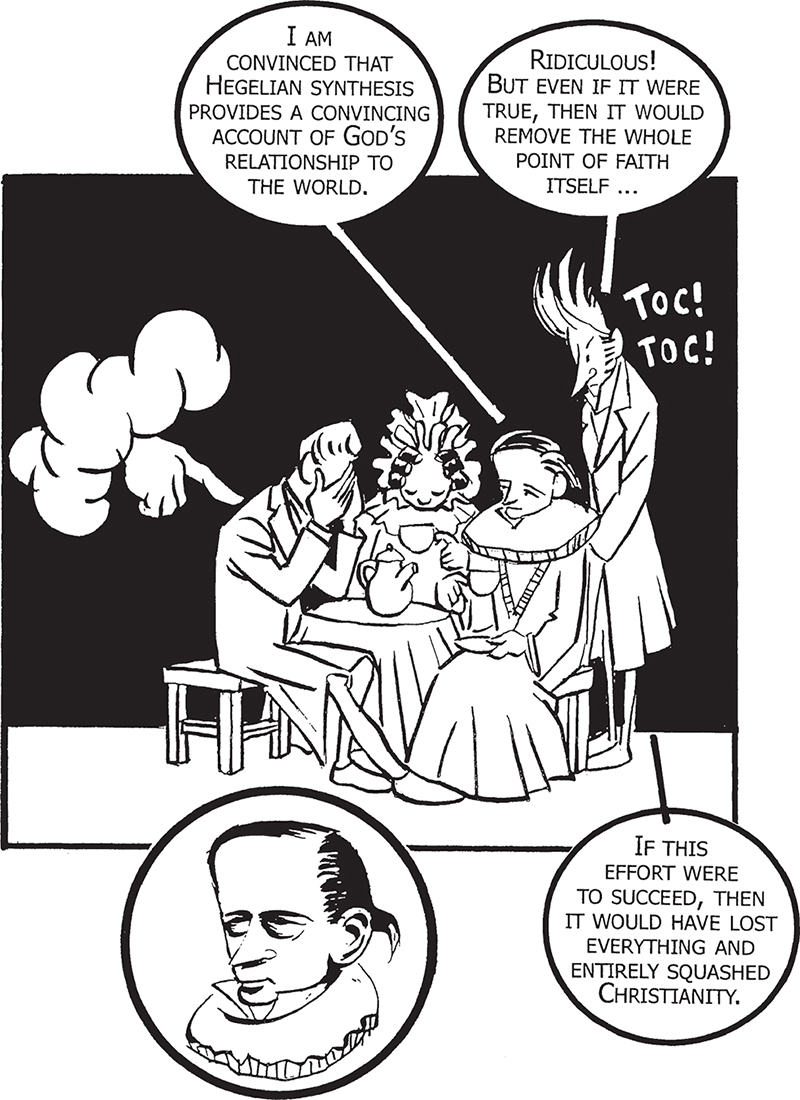

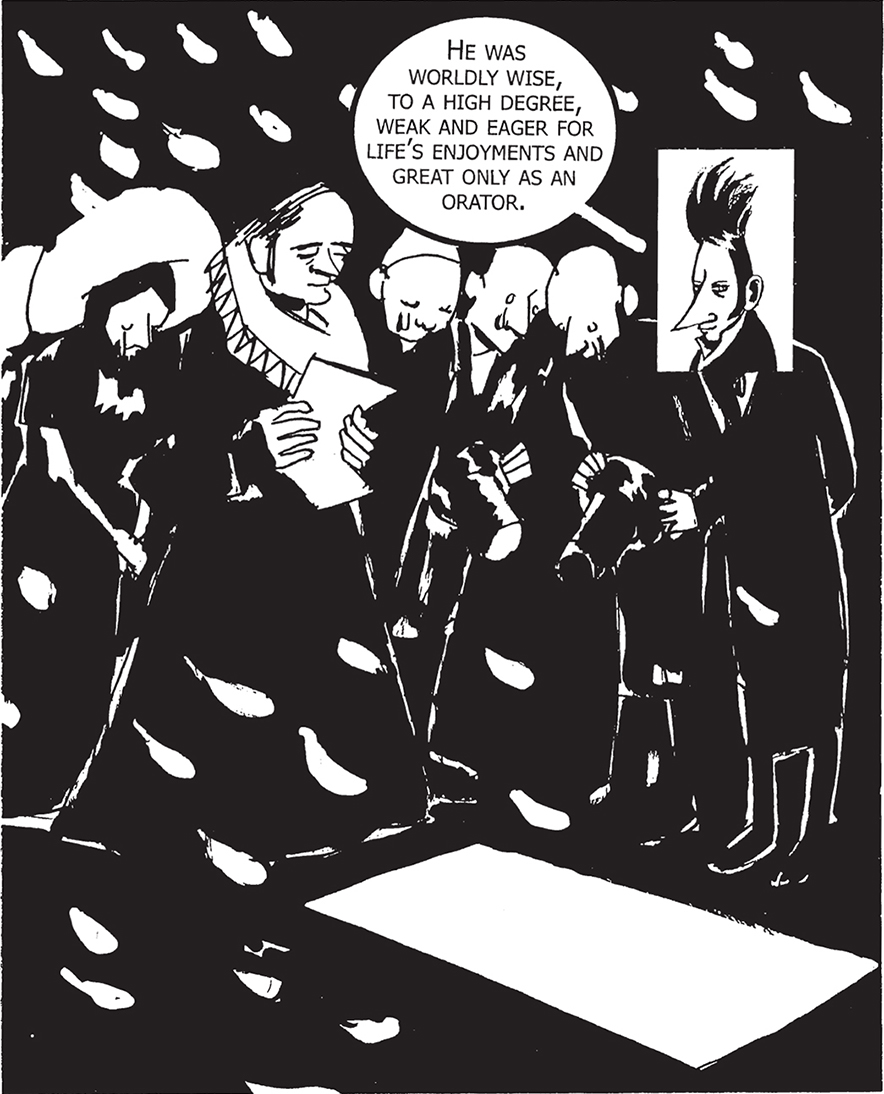

One Danish theologian who professed Hegelian views was Hans Lassen Martensen (1808–84). He was a major figure in Copenhagen society, a frequent visitor to the Kierkegaard household and a reasonably tolerant and liberal cleric who tried to moderate some of Michael Kierkegaard’s more pessimistic views about his vengeful God.

I AM CONVINCED THAT HEGELIAN SYNTHESIS PROVIDES A CONVINCING ACCOUNT OF GOD’S RELATIONSHIP TO THE WORLD.

RIDICULOUS! BUT EVEN IF IT WERE TRUE, THEN IT WOULD REMOVE THE WHOLE POINT OF FAITH ITSELF …

IF THIS EFFORT WERE TO SUCCEED, THEN IT WOULD HAVE LOST EVERYTHING AND ENTIRELY SQUASHED CHRISTIANITY.

Believing in Christianity means accepting fundamentally absurd doctrines, especially those that define its founder.

For Hegel, Christ’s appearance on earth – the Incarnation – was a “pre-reflective” expression of the potential synthesis of the universal and particular, the finite and the infinite. The story of Christ, in other words, was a primitive kind of “picture thinking” that hinted at a deeper and more conceptual truth that later philosophers would clarify. Christ was no more than a concrete example of the conceptual unity attainable through the synthesis of apparently irreconcilable opposites.

CHRIST THE GOD-MAN IS AN EXTRAORDINARY COMBINATION WHICH DIRECTLY CONTRADICTS THE UNDERSTANDING.

NEVERTHELESS, IT REVEALS THE TRUTH THAT THE DIVINE AND THE HUMAN NATURES ARE NOT IMPLICITLY DIFFERENT.

The divine and the human can reach a dialectical synthesis because human beings have the “divine” in them. By being fully rational, the human mind gets close to the divine and so becomes Christ-like. Hegel therefore frowned on those Christians who believed in introspection, trusted their own individual consciences and worshipped a wholly transcendent God.

CHRISTIANITY IS MOST VALUABLE AS A “FOLK RELIGION” THAT UNDERPINS THE CIVIC LIFE OF A COMMUNITY …

THE MORAL LIFE OF THE STATE AND THE RELIGIOUS SPIRITUALITY OF THE STATE ARE THUS RECIPROCAL GUARANTEES OF STRENGTH.

Kierkegaard argued both that the object of Christian faith is inherently paradoxical and that the act of Christian faith is itself absurd. There is a profound irrationality at the heart of Christianity that philosophy can never “absorb”. The incarnation of Christ – the historical and finite existence of an infinite deity in human form – is utterly self-contradictory. It is logically impossible for the “temporal” and the “eternal” to co-exist.

THAT GOD HAS EXISTED IN HUMAN FORM, BEEN BORN, GROWN UP AND SO FORTH, IS SURELY THE ABSOLUTE PARADOX.

THIS PARTICULAR INDIVIDUAL HUMAN BEING – WHO LOOKED LIKE OTHER HUMAN BEINGS, TALKED LIKE THEM AND FOLLOWED THEIR CUSTOMS – WAS … THE SON OF GOD!

And if God is a “transcendent” being, totally removed from the material world, how can Christ’s existence on earth be explained?

For Kierkegaard, we are all pitiful and finite temporal beings whose understanding is woefully limited by our earthly situation. To think that we can ever have a God-like perspective, outside of space and time, is the height of folly. No one, not even Hegel, can reach a vantage point of “pure thought”.

HEGEL IMPLIED THAT HUMAN BEINGS AND GOD ARE DIFFERENT IN DEGREE …

I INSIST THAT THEY ARE IRRECONCILABLY DIFFERENT IN KIND.

“As long as anyone exists, he is essentially an existing individual whose essential task is to concentrate upon inwardness in existing; while God is infinite and eternal.”

Kierkegaard also challenged the long-held philosophical view about truth. The traditional philosophical conception of knowledge is one that downgrades individual truths, insists on going beyond a private point of view and looks at things dispassionately and disinterestedly. Kierkegaard despised this exclusive definition of truth.

IF SOMETHING IS TO BE TRUE, IT HAS TO BE OBJECTIVE.

IF TRUTH HAS TO BE TRUE FOR ALL, THEN IT IS NO MORE THAN A CONSENSUS OF GENERALIZED OPINION.

Everyone is aware of the fact that some emotional truths are subjective. I love my cat, but that’s not a truth I expect anyone else to share. The indifference of others doesn’t mean it isn’t true – for me.

The same is true for the individual who has to make life-changing decisions that seem “true” for him or her. Very often these decisions have to be made at a particular moment, rapidly, in particular situations. There isn’t a rule or guidebook to tell you what is “true for you”. Kierkegaard frequently makes this point in exaggerated aphorisms like this …

“Our age is essentially one of understanding and reflection, without passion. Nowadays, not even a suicide kills himself in desperation. Before taking the step he deliberates so long and so carefully that he literally chokes with thought. He does not die with deliberation, but from deliberation.”

Another example of such subjectivity is religious “truths” for which the individual cannot get any external, rational warranty. This is obviously the case with a set of doctrines that are inherently paradoxical. “When subjectivity is the truth, the truth becomes objectively a paradox; and the fact that the truth is objectively a paradox shows in turn that subjectivity is the truth.”

IF THE OBJECT OF FAITH (CHRIST) IS PARADOXICAL, THEN FAITH ITSELF HAS TO BE EQUALLY UNCERTAIN AND IRRATIONAL.

AND BECAUSE IT CAN NEVER BE MADE OBJECTIVE, IT MUST BE SUBJECTIVE.

However ingenious his dialectic, Hegel cannot dispel the extraordinary contradictions lying at the heart of the Christian faith. True Christians must choose their own certainty – about an objective uncertainty – and enter a paradoxical state of mind that necessitates risk and a “leap of faith”. So what is “faith”?

Faith is usually defined as a belief in something for which there isn’t any proof or evidence. St Thomas Aquinas suggested that faith was for those without the intelligence or learning to follow his own complex philosophical “proofs”. For Kierkegaard, faith is not some kind of second-rate belief, but a “passionate inwardness”, the acceptance of a unique and precarious way of life. It has nothing to do with knowledge, proof or verification.

FAITH IS LYING OUT OVER A DEPTH OF 70,000 FATHOMS OF WATER …

Christian faith is something that utterly transforms an individual’s life, in the way that evidence, proof or knowledge never could. So, for example, if scientific evidence were found to show that matter can be made from “nothing”, it would be interesting, but it wouldn’t actually transform many people’s lives. Faith is more like sight than knowledge – something immediate and vital – which means that to prove Christianity would actually make it emotionally vacuous.

WHEN FAITH BEGINS TO LOSE ITS PASSION, ONLY THEN DOES A PROOF BECOME NECESSARY.

Faith involves a relationship with an invisible, eternal and transcendent God utterly remote from our temporal world, a relationship that often can produce feelings of guilt and despair in those committed to it (feelings that anyone outside of the religious life would just not understand). Kierkegaard’s own brand of Christianity was a belief system that seemed to justify his own constant feelings of dread and guilt. He understood that perfectly well.

CHRISTIANITY IS CERTAINLY NOT MELANCHOLY; IT IS, ON THE CONTRARY, GLAD TIDINGS – FOR THE MELANCHOLY.

We can occasionally glimpse eternity in rare moments of personal revelation. But it has little in common with the orthodox Christian heaven – a total commitment to Christ’s teachings in the past and his presence now – a whole way of life which abandoned all other “spheres of existence”, even the ethical one. And that is what Fear and Trembling is primarily about.

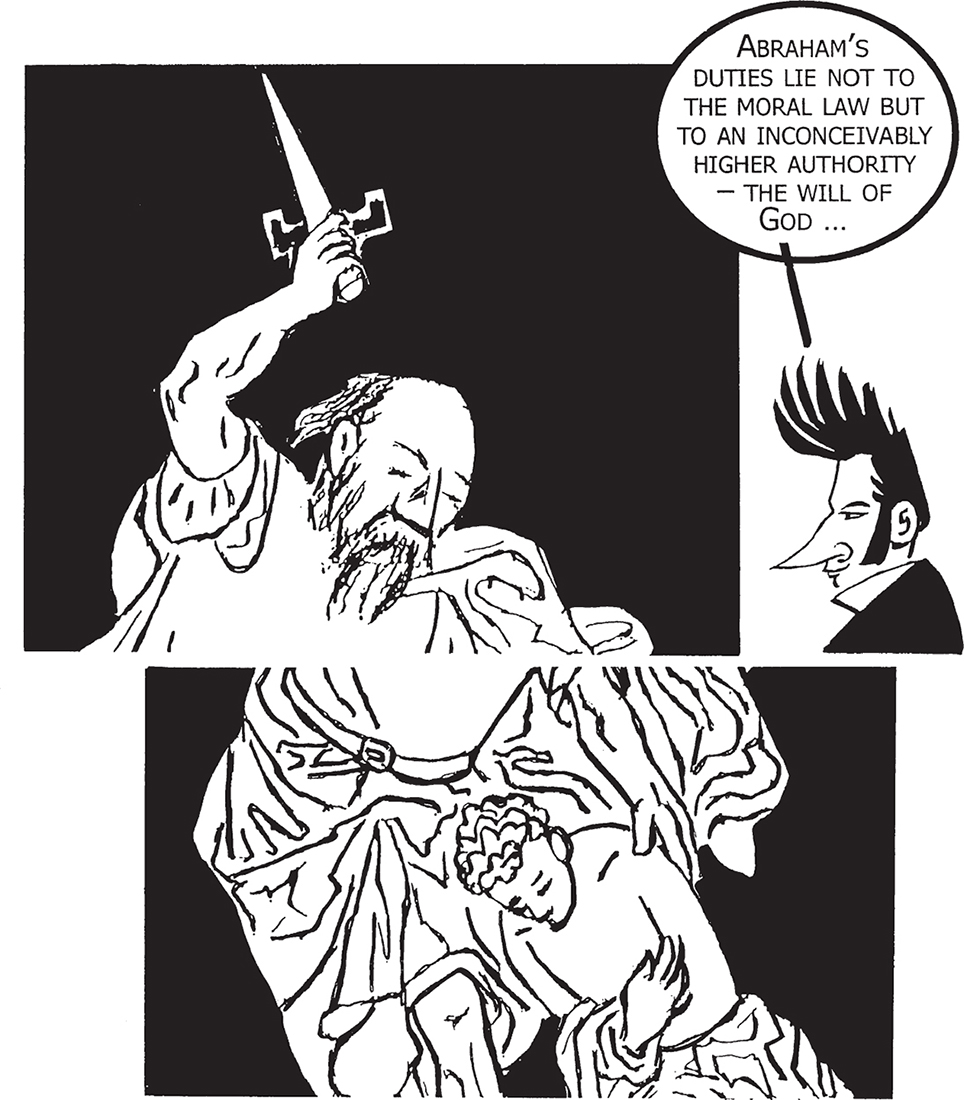

This book was published simultaneously with Repetition but is very different. Fear and Trembling is narrated by Johannes de Silentio, a man trying to come to terms with commitment to a religious way of life. His narrative centres on the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac. Abraham hears God’s voice telling him to sacrifice his son on the top of the mountain; he obeys the command without question, and prepares to kill his first-born.

“Abraham built an altar there and bound Isaac his son, and laid him upon the altar. And Abraham stretched forth his hand and took the knife to slay his son.”

Fortunately, a sympathetic angel intervenes, and Isaac is saved. A “ram caught in a thicket by his horns” acts as a substitute. But Johannes remains shocked by the story. It seems such an unnatural, irrational and unethical act to even contemplate carrying out, and he finds it hard to accept the praise heaped upon Abraham’s head for his obedience to God’s command.

EITHER ABRAHAM WAS EVERY MINUTE A MURDERER OR WE ARE CONFRONTED BY A PARADOX WHICH IS HIGHER THAN ALL MEDIATION.

There is clearly a fundamental difference between the “ethical sphere” (as recommended by Judge Wilhelm in Either/Or) and this strange and disturbing “religious sphere” which seems to sanction infanticide. Kierkegaard was fond of taking stories from the Bible and re-examining them in this sort of way. And it is the tale of an imperious old patriarch and his more timid son, a story that appealed to Kierkegaard for rather obvious reasons.

THERE ARE SOME MEN WHOSE DESTINY IS TO BE SACRIFICED IN ONE WAY OR ANOTHER.

After a long struggle, Johannes comes to accept that, when a human being encounters God so directly, normal human ethics and codes of behaviour no longer apply.

FAITH IS PRECISELY THIS PARADOX, THAT THE INDIVIDUAL AS THE PARTICULAR IS HIGHER THAN THE UNIVERSAL.

Choosing total obedience to God’s word requires a huge “leap” from the everyday world of traditional moral beliefs into a way of life that can make outrageous demands on the individual. In the end, Johannes recognizes the astonishing beauty of Abraham’s faith, but is reduced to “fear and trembling” when he asks himself if he could do the same. He concludes that he personally is not ready to move on to this utterly incomprehensible way of life.

Abraham’s test is indeed a puzzling and disturbing story. Kierkegaard is deliberately overstating his case with this shocking example of how the religious life and the ethical life can be so far apart. The tale is also a veiled criticism of Hegel’s plan to incorporate Christianity into the ethics of civic life. “I for my part have applied considerable time to understanding Hegelian philosophy, and believe that I have understood it fairly well. Thinking about Abraham is another matter, however: then I am shattered.”

COULD YOU DO WHAT ABRAHAM WAS ASKED TO DO?

The irrationality of Abraham’s choice seems so absolute. It would be hard to imagine a greater crime than killing your own child. Most of us would maintain that his story of “voices” and his “reasons” were those of a madman. He could never justify his act to others. But the will of God, apparently, has little to do with the civic life of the community.

ABRAHAM’S DUTIES LIE NOT TO THE MORAL LAW BUT TO AN INCONCEIVABLY HIGHER AUTHORITY – THE WILL OF GOD …

Perhaps it is best to think of Kierkegaard’s story as a challenge. The reader must decide whether to excuse or condemn Abraham’s obedience to divine command. Kierkegaard, as always, leaves the choice open. But his point is made: there is a huge difference between shared social norms and a system of values based on a wholly mysterious transcendent source.

True believers like Abraham are essentially asocial. They will always come into conflict with the prevailing social norms of their society, whether these are Judaic, Roman Catholic, Communist or Lutheran. Kierkegaard certainly appears to commend what he calls “the teleological suspension of the ethical” – the claim that certain people like Abraham, a “knight of faith”, are exempt from the moral considerations that the rest of us hold, even if he never says so directly.

BY HIS ACT HE TRANSGRESSES THE ETHICAL ALTOGETHER AND HAS A HIGHER CAUSE OUTSIDE IT …

The French Existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–80), a great admirer of Kierkegaard, pointed out, rather dryly, that Abraham actually made two choices.

HE HAD ALREADY MADE A RATHER QUESTIONABLE CHOICE – TO BELIEVE THAT THE VOICE HE HEARD, COMMANDING HIM TO PERFORM SUCH AN APPALLING ACT, WAS INDEED THE VOICE OF GOD.

THE “ANGUISH” HE WOULD FEEL, OVER HIS SUBSEQUENT CHOICE – TO KILL HIS SON – MIGHT HAVE BEEN EVEN GREATER, IF HE HAD THOUGHT OF THAT FIRST.

I EXPLORE THIS “KNOWLEDGE” OF PERSONAL GUILT AND SIN AS A PSYCHOLOGICAL STATE OF MIND IN THE CONCEPT OF DREAD.

The narrator of this odd book is Vigilus Haufniensis. He begins by remarking on the fact that “dread” (sometimes translated as “anxiety”) is something that most philosophers have avoided examining. (Nowadays, of course, it is a subject examined almost to death by psychoanalysts.) The subtitle of the book is very strange – A Simple Psychological Deliberation Directed Towards the Dogmatic Problem of Original Sin.

THE BOOK WILL INVESTIGATE THE PROBLEM OF ANXIETY AS BOTH A PSYCHOLOGICAL AND A THEOLOGICAL ISSUE.

The Concept of Dread is a deeply autobiographical work that indirect narrative methods do little to disguise. Kierkegaard begins by drawing a distinction between “dread” and “fear”. Fear is easy to explain.

FEAR IS A NATURAL HUMAN EMOTION WHEN AN INDIVIDUAL IS FACED WITH SOME KIND OF SPECIFIC DANGER.

BUT “DREAD” IS DIFFERENT … A VAGUE FEELING OF MELANCHOLY AND UNEASE THAT NEVER SEEMS TO GO AWAY.

Dread or anxiety plagues certain individuals who are normally unable to specify the cause of it.

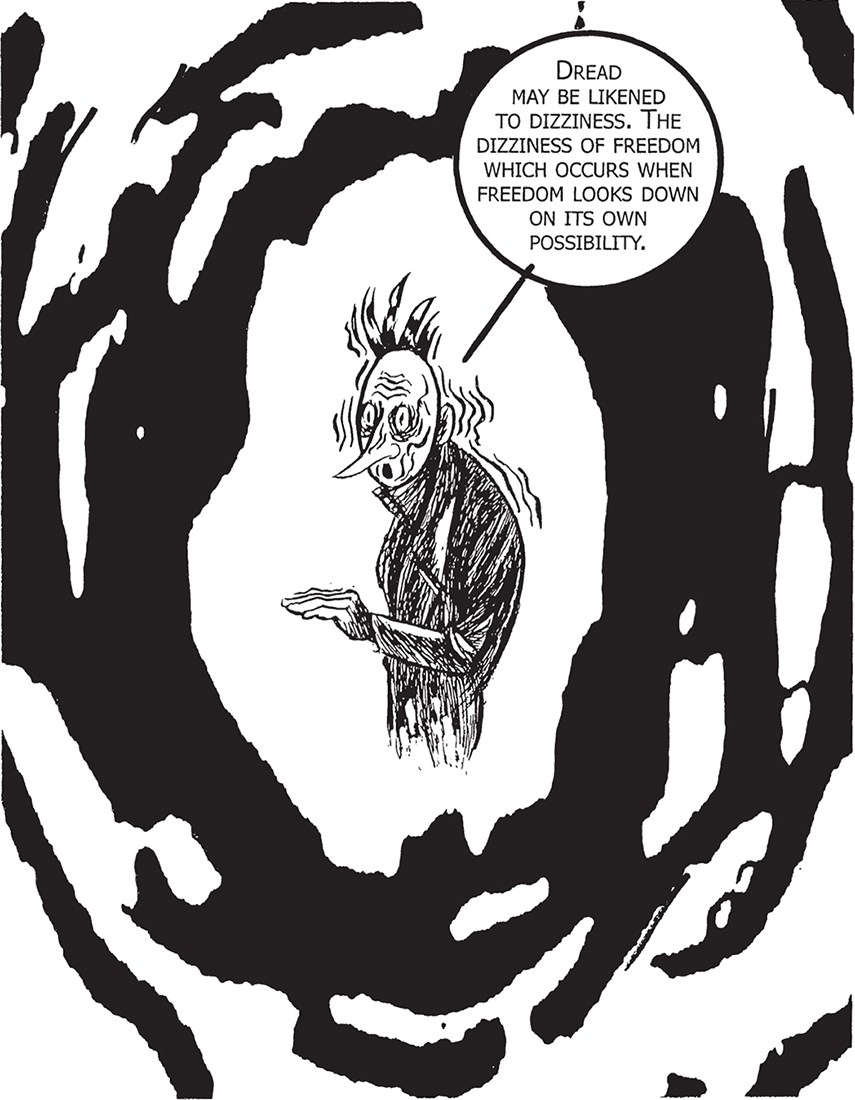

Dread is a symptom of “freedom’s appearance before itself in possibility”. Kierkegaard is saying that we are all free to choose what we do and so invent who we are. This is a fact most people are normally only half aware of, because they don’t like to think about it too much. It’s much easier to be a “philistine” member of the “public” and let others choose for you. But the knowledge of that fundamental freedom is always there, and the anxiety never quite goes away.

DREAD MAY BE LIKENED TO DIZZINESS. THE DIZZINESS OF FREEDOM WHICH OCCURS WHEN FREEDOM LOOKS DOWN ON ITS OWN POSSIBILITY.

Kierkegaard clarifies the idea with a Biblical example. Everyone knows the story of Adam and Eve. Why did Adam break God’s commandment and eat the apple from the Tree of Knowledge? The usual explanation is that the very prohibition tempted Adam and aroused his desire to break it. Kierkegaard’s explanation is different. The prohibition awoke a dread of breaking it, which made Adam perpetually anxious.

THE PROHIBITION MADE HIM ANXIOUS, BECAUSE THE PROHIBITION AWAKENS THE POSSIBILITY OF FREEDOM IN HIM, THE ALARMING POSSIBILITY OF DOING IT.

Adam eats the fruit to free himself of his constant anxiety. God must have known that the temptation was immense. But, in the final analysis, the decision was Adam’s alone and no one else’s, so he has to take responsibility for it.

Kierkegaard’s analysis of this “fear of freedom” is an intriguing one, pursued and expanded on by philosophers as different as Jean-Paul Sartre and Erich Fromm (1900–80). It can make individuals and whole societies “inauthentic”. People, as individuals or en masse, are too often happy to “escape” this fear by retreating into an obedience to ideologies dictated by others.

BUT THEY CAN NEVER BE TRULY SAID TO “EXIST”.

THIS WAY THEY CAN ESCAPE THEIR ANXIETY AND REPLACE IT WITH A FEELING OF CERTAINTY AND SECURITY.

The rest of The Concept of Dread contains odder ideas. Adam’s “original” sin is inherited by everyone. Even worse, each subsequent generation adds on sins of their own, a millstone that grows larger and heavier from generation to generation as the human race progresses. Kierkegaard seems to have had rather Hegelian views about individuals and families in this regard.

THE WHOLE FAMILY PARTICIPATES IN THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE INDIVIDUAL IN THE WHOLE FAMILY.

So presumably, Michael’s sin of blasphemy is one that his son also had to carry with him, to the grave.

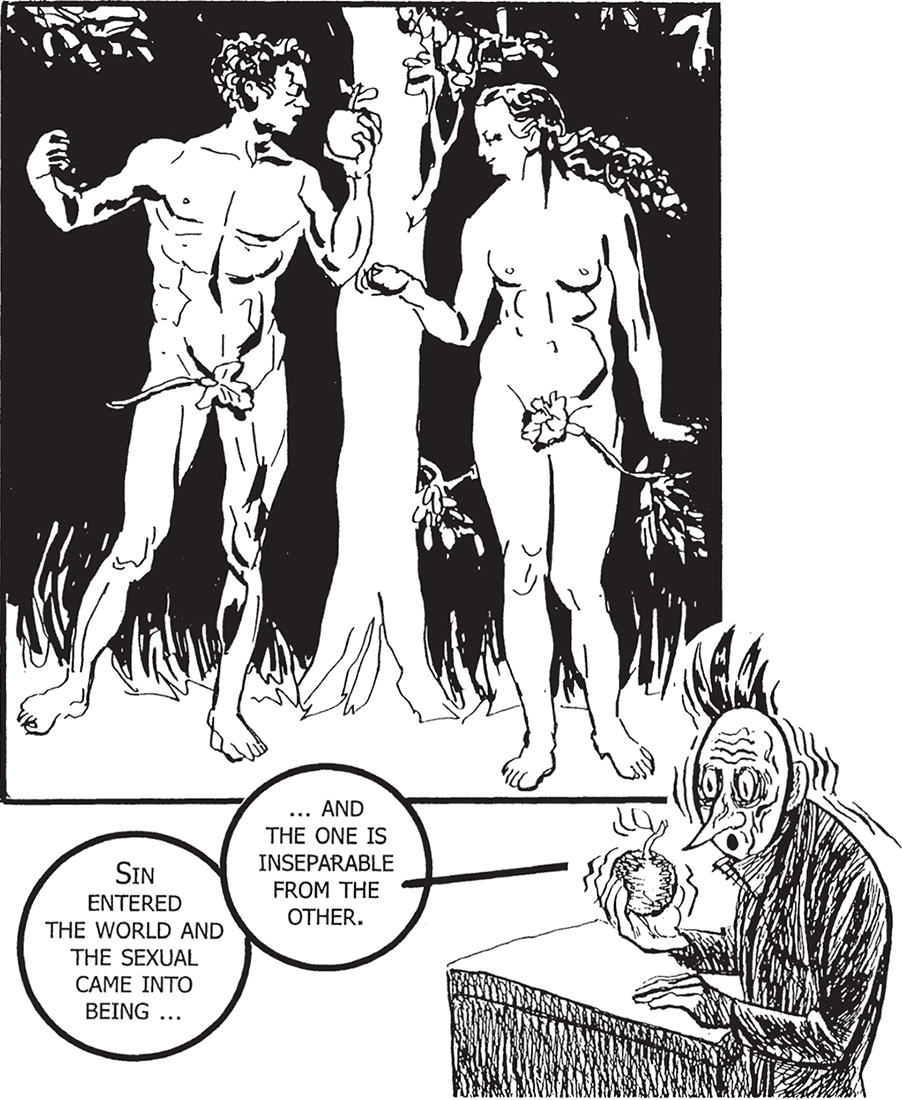

Kierkegaard’s views on human sexuality are also rather grim.

… AND THE ONE IS INSEPARABLE FROM THE OTHER.

SIN ENTERED THE WORLD AND THE SEXUAL CAME INTO BEING …

For Kierkegaard, this explains why thoughts of sexuality are always accompanied by feelings of anxiety. Sexuality is associated with Adam’s original dread about breaking God’s laws, the first sin and God’s curse. There is something Manichean about Kierkegaard’s depiction of his fellow human beings – as potentially pure spirits “trapped” in physical corruption. Kierkegaard undoubtedly had extreme anxieties about his own sexuality which he tried to escape by thinking of his own life as a progressive journey towards an ascetic life of “pure spirit”. “The spirit has conquered so that the sexual is forgotten and remembered only in oblivion.”

Kierkegaard was the first philosopher to recognize that in our modern age many people experience feelings of “anxiety” for reasons not easy to comprehend.

PERHAPS WE ARE CONFUSED BY TOO MANY “FREEDOMS” THAT CAPITALIST WESTERN SOCIETIES SEEM TO OFFER US …

ANXIETY COMES FROM NO LONGER THINKING OF OURSELVES AS “SPIRITUAL BEINGS” AS OUR ANCESTORS DID.

No! PEOPLE FEEL “ALIENATED” FROM THE PRODUCTS OF THEIR LABOUR, TRAPPED IN CEASELESS COMPETITION, WITH NO COHERENT SENSE OF COMMUNITY.

ALL OF THESE FACTORS, AND OTHERS BESIDE, CONTRIBUTE TO THE SYMPTOMS OF “DREAD”.

Stages on Life’s Way continues Kierkegaard’s exploration of his own life and ideas about women, marriage, ethics, psychology, guilt and responsibility. Five fairly cynical male speakers discuss women and love and conclude that neither should be taken very seriously.

YOU’VE MET FOUR OF US BEFORE …

JUDGE WILHELM ARRIVES TO DEFEND MARRIAGE AGAINST ITS (BY NOW) DRUNKEN CRITICS.

In one section of the book, “Guilty? Not Guilty?”, “Frater Taciturnus” provides a detailed account of another year-long engagement that ended in disaster. All the complex feelings, thoughts and motives of the young man involved (called “Quidam”) are analyzed and discussed in detail.

HIS NATURAL DISPOSITION IS MELANCHOLIC – THOUGH HE CONCEALS IT UNDER A MASK OF JOVIALITY.

THERE ARE ALSO HUGE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN HIM AND HIS FIANCÉE, ESPECIALLY IN THEIR RELIGIOUS VIEWS.

MARRIAGE MEANS ABSOLUTE FRANKNESS ON BOTH SIDES – A VERY DEMANDING REQUIREMENT – SO I CALLED THE ENGAGEMENT OFF.

Like Kierkegaard, Quidam is obsessed by responsibility. If there is the remotest possibility of the marriage going wrong, then he should not commit to it. “An ethical obligation cannot be cancelled out by the thought that it may not happen.”

Quidam bravely attempts to examine the features and the causes of his unceasing melancholy. These are a complicated mixture of his own feelings of guilt and the depressive tendencies he inherited from his father – an old man who had the most horrible nightmares. Quidam, like Kierkegaard, shared a bedroom with his father, and at last begins to realize that the old man was a bit of a monster.

IF EVER THERE WAS AN AGONY OF SYMPATHY, IT IS THAT OF HAVING TO BE ASHAMED OF ONE’S OWN FATHER, OF THE PERSON ONE LOVES BEST AND OWES MOST.

The book ends on a lighter note. Quidam ironically recognizes that life is suffering, and the way out of the swamp of personal despair is to make the leap into a third “stage” – the religious way of life.

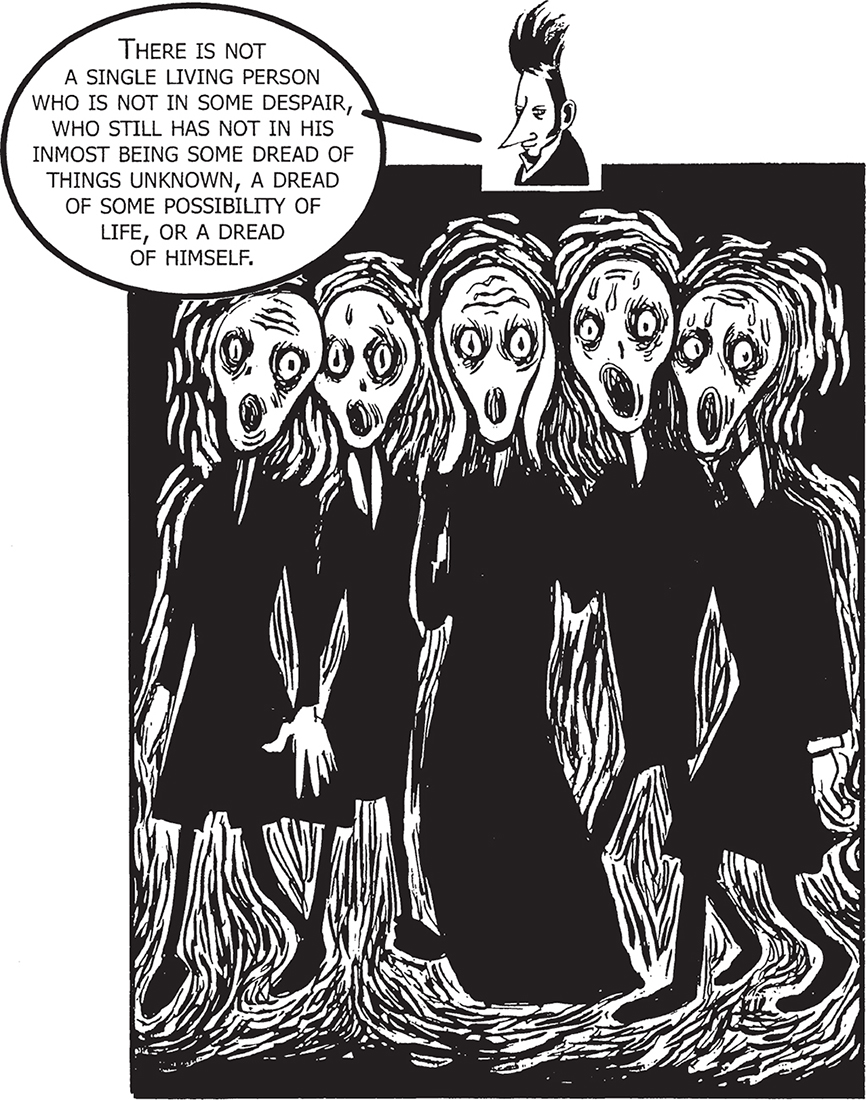

Kierkegaard thought The Sickness Unto Death was the best book he ever wrote, an opinion that not all of his readers now share. The theme is, again, despair – a state of mind most people are in for most of the time, even if they are not always consciously aware of it.

THERE IS NOT A SINGLE LIVING PERSON WHO IS NOT IN SOME DESPAIR, WHO STILL HAS NOT IN HIS INMOST BEING SOME DREAD OF “HINGS UNKNOWN, A DREAD OF SOME POSSIBILITY OF LIFE, OR A DREAD OF HIMSELF.

Fortunately, the book tells us how to cope. As human beings, we are all given a unique individual self. For most people, this self is given by nature; but for a Christian, it is the product of a relationship to God. Feelings of despair are experienced by both, in different forms. Normally we assume that despair is a feeling that has a specific cause – like being abandoned by a lover.

BUT I REFER HERE TO THE VAGUE SORT OF UNEASE CAUSED BY A DESPONDENCY ABOUT THE SELF.

THIS UNEASE COMES ABOUT BECAUSE ACQUIRING A TRUE SELF IS A TASK – SOMETHING THAT HAS TO BE WORKED AT AND DEVELOPED.

As the human self progresses, it understands more about everything, including itself. But people who drift through life without recognizing the importance of this task will never become authentic human beings. Even a brilliant scholar, without this kind of self-awareness, can never become a successful human being, only some sort of brilliant analytical automaton.

THE MORE UNDERSTANDING INCREASES, THE MORE IT BECOMES A KIND OF INHUMAN UNDERSTANDING.

The same is true of such other human attributes as sensitivity and the will. If your sensitive nature is directed at something impossibly large, like “all humanity”, then it will become unreal and inhuman. “The Will” should also be exercised in immediate situations. The more “will” someone possesses, the more self is attained. But most people are without much willpower. They meander through life and avoid the challenging issue of who they are. Kierkegaard’s views on will parallel those of several other 19th-century philosophers – in particular Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900).

THE WILL DIRECTS ALL THINGS …

THE WORLD IS THE WILL TO POWER AND NOTHING ELSE.

THE GREATEST DANGER, THAT OF LOSING ONESELF, CAN PASS OFF IN THE WORLD AS QUIETLY AS IF NOTHING AT ALL HAD HAPPENED.

Vague feelings of despair are an inevitable by-product of a “wilful” neglect of the self. For many, this is a deliberate strategy – to avoid the problem by ignoring it. For others, the avoidance strategy involves inventing some new self that they picture to themselves as a possibility never seriously achieved. Such individuals become “strangers” to themselves and on occasion become suicidal.

THEY WISH TO DO AWAY WITH THEMSELVES AND BECOME NOTHING.

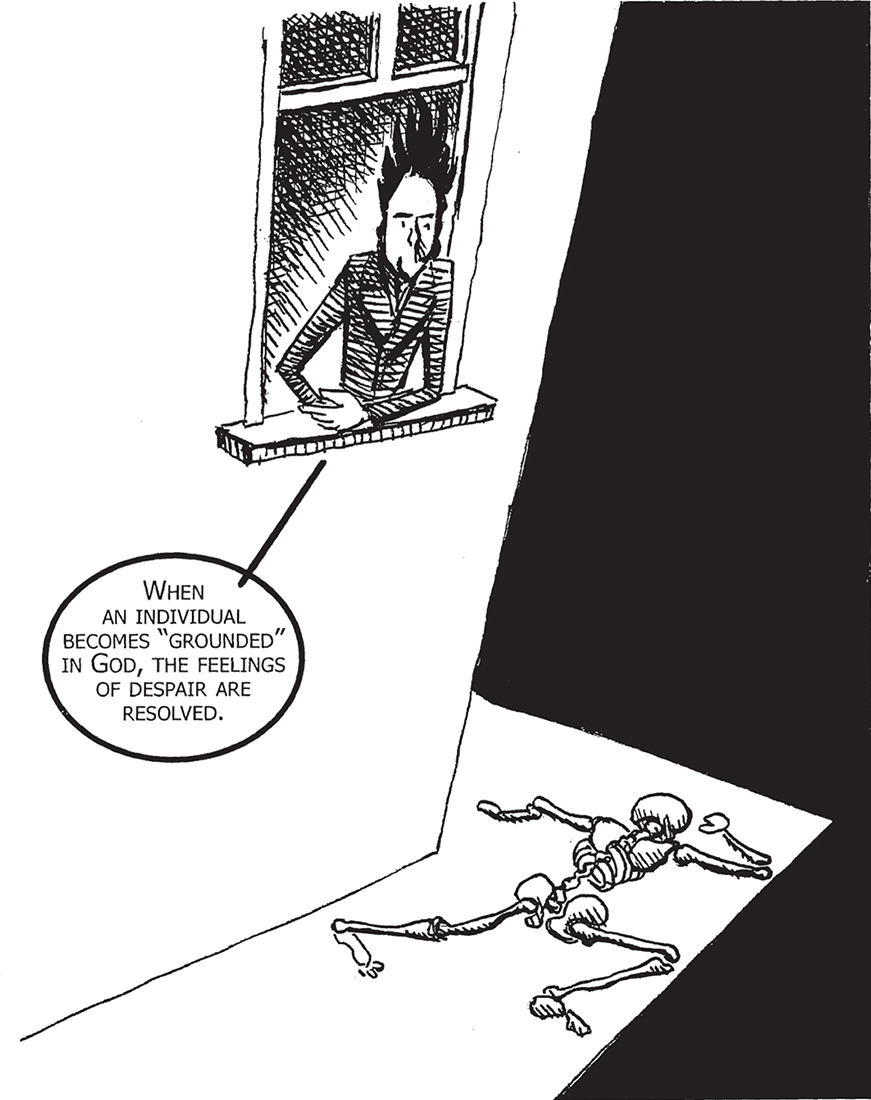

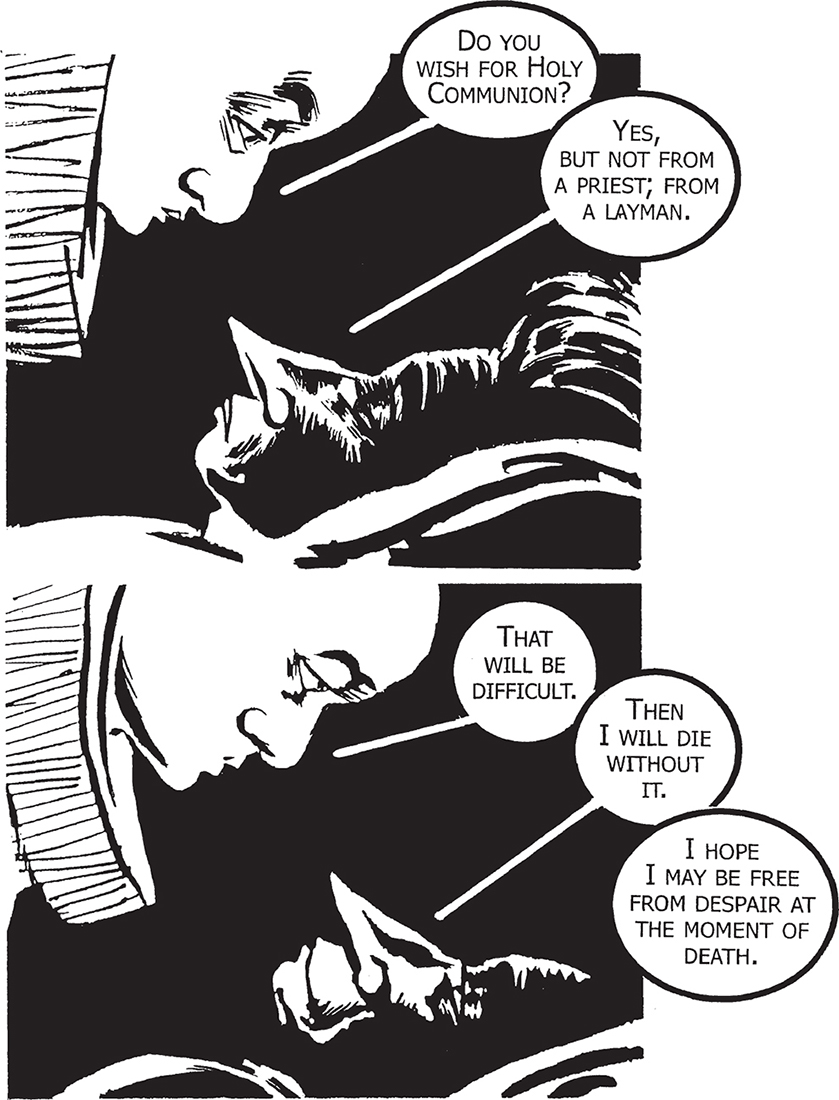

For the “natural” man, death is tragic – the end of life. For a Christian, death is an event of less significance – merely one stage towards an eternal life. But for the committed Christian, these vague feelings of melancholy can turn into something much worse – despair, which is “sickness unto death”. Paradoxically, the more one strives to be a good Christian, the more one becomes aware of one’s own guilt, and its companion – a despairing sense of sin. The remedy is faith.

WHEN AN INDIVIDUAL, BECOMES “GROUNDED” IN GOD, THE FEELINGS OF DESPAIR ARE RESOLVED.

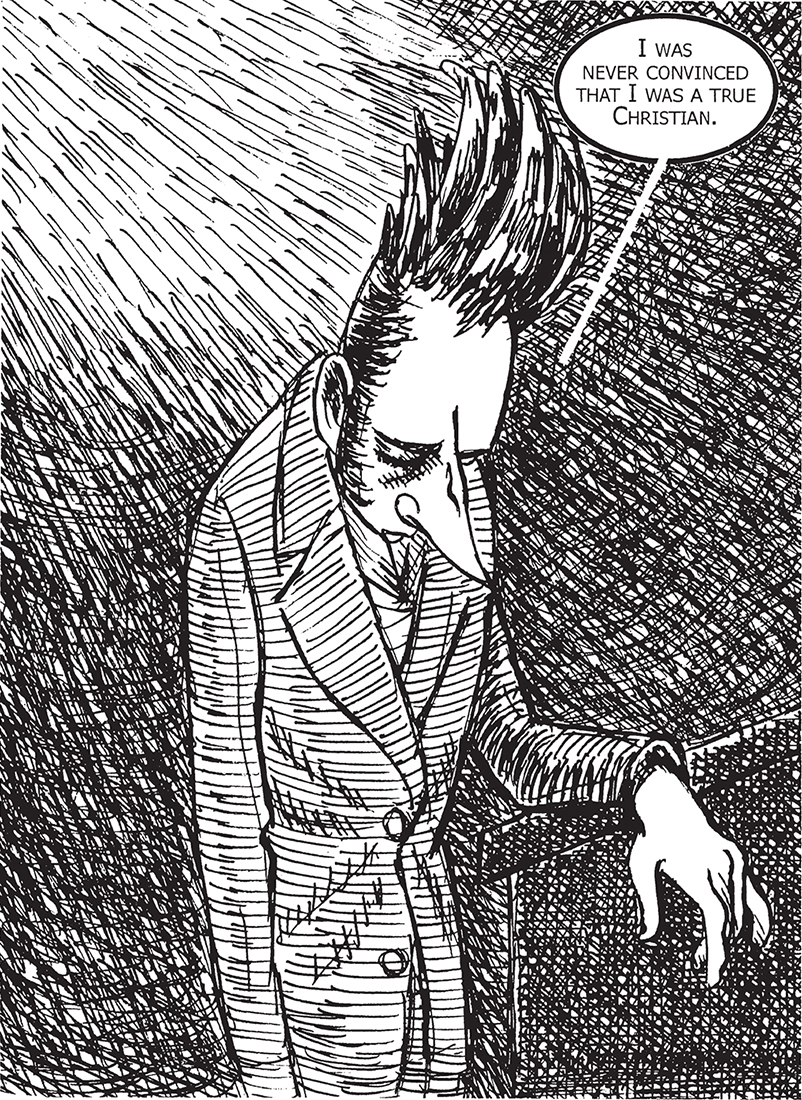

The Sickness Unto Death is the usual conflicting mixture of very incisive psychology and less immediately attractive Christian theology. “Being oneself” was not effortless – it involved a long struggle and a ruthless kind of honesty that most people would rather avoid. Kierkegaard felt he had to engage in this “self-struggle”, and it destroyed what little happiness he might have achieved. He was always highly self-critical.

I WAS NEVER CONVINCED THAT I WAS A TRUE CHRISTIAN.

In one of his later books, Training in Christianity (1850), Kierkegaard declares that a true Christian had to be “contemporaneous” with Christ. Most 19th-century Danish citizens would be horrified if they ever chanced to meet Jesus – a carpenter’s son accompanied by beggars and lunatics.

JOIN HIM? I HAVE NOT GONE MAD YET! THE MESSIAH WILL APPEAR QUITE DIFFERENTLY.

HE HAS NO DOCTRINE, NO SYSTEM …

LOOK WHO RUNS AFTER HIM – WORTHLESS STREET-LOUNGERS AND TRAMPS!

EITHER YOU ARE SCANDALIZED BY CHRIST OR YOU MAKE HIM YOUR WHOLE WAY OF EXISTENCE. THERE IS NO MIDDLE WAY.

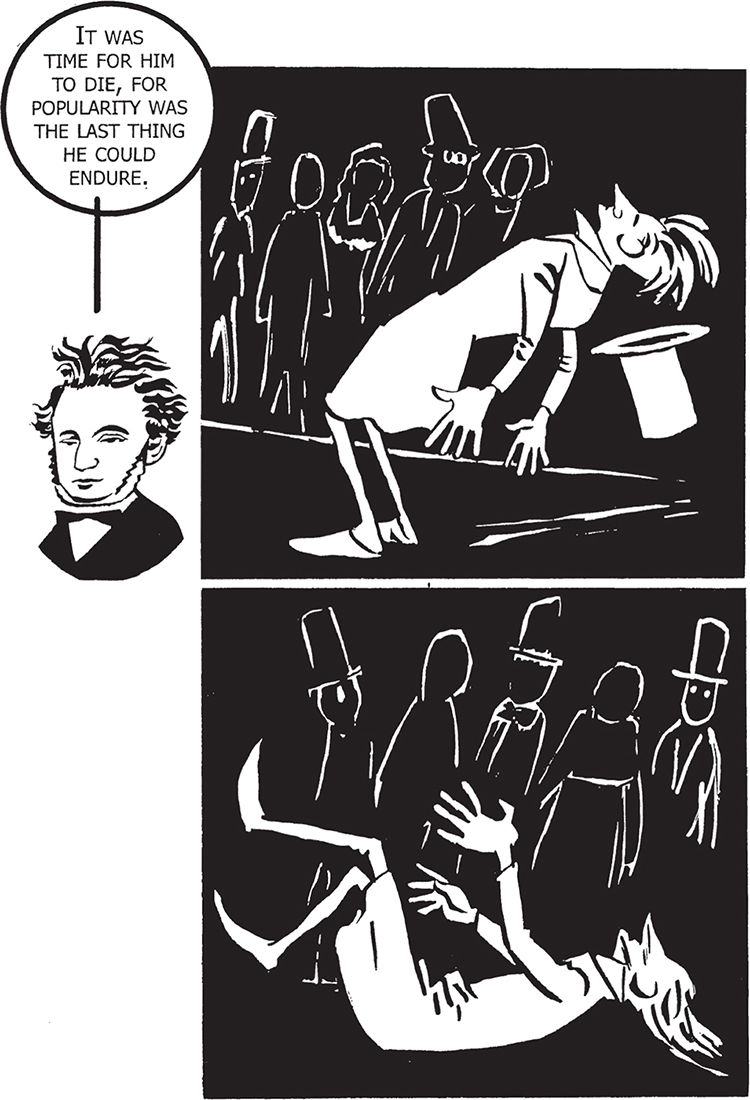

This doctrine completely dominated Kierkegaard in his final years, brought him ridicule and unhappiness, and outraged the State Church.

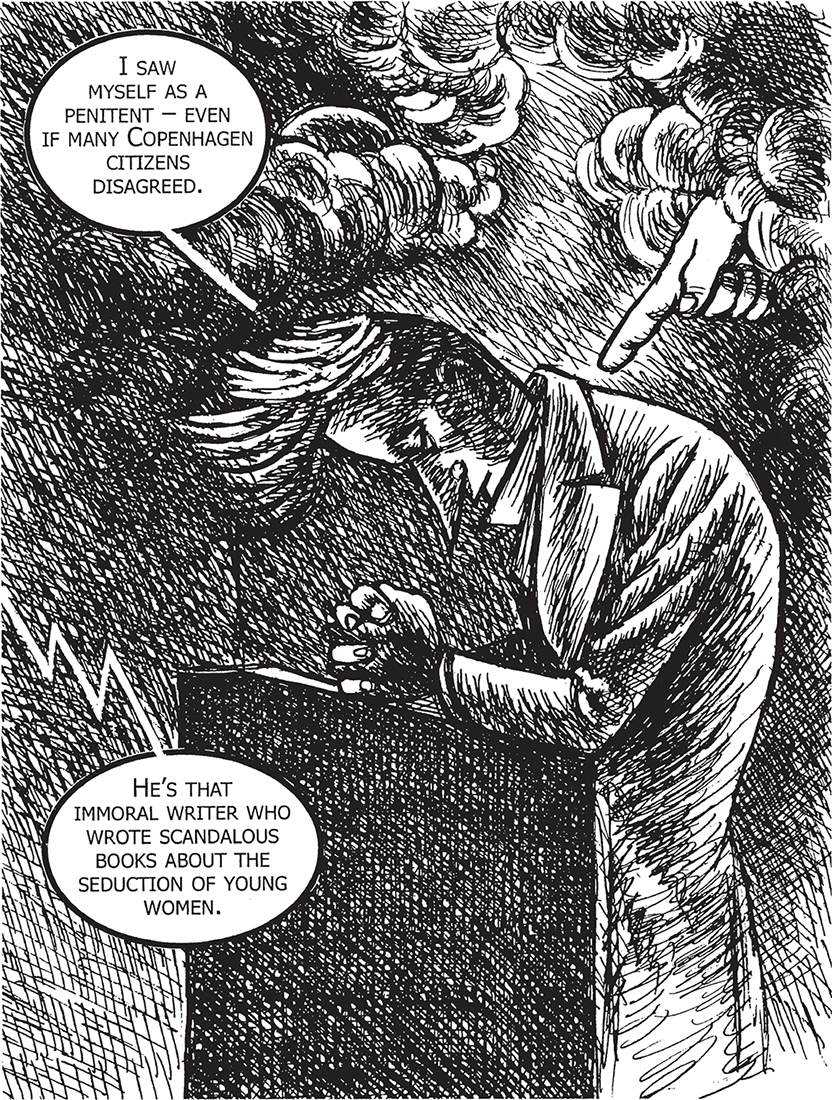

After the broken engagement with Regine, Kierkegaard believed he had to choose between the life of the worldly aesthete or “the cloister”. For a Danish Protestant, the monastic life wasn’t really an option, so he spent his latter years as a recluse, reading theology and philosophy and writing his extraordinary books. Occasionally, he had “glimpses of the infinite”, but he was never a fervent mystic or much of a radical dissenter.

I SAW MYSELF AS A PENITENT – EVEN IF MANY COPENHAGEN CITIZENS DISAGREED.

HE’S THAT IMMORAL WRITER WHO WROTE SCANDALOUS BOOKS ABOUT THE SEDUCTION OF YOUNG WOMEN.

Denmark was an absolutist monarchy with Protestant Lutheranism as its official State religion, and Kierkegaard still retained thoughts of becoming a Lutheran pastor in a small country parish. Bishop Mynster, the old family friend who had debated theology with his father, thought that Kierkegaard’s own religion was “pitched too high” for him ever to be a humble country preacher – a judgement that now seems rather astute. Kierkegaard was rather too keen on self-denial, suffering and hellfire to suit most rural parishioners.

WHY DON’T YOU FOUND ONE OF YOUR OWN?

WHEN I ASKED HIM IF THERE MIGHT BE A FREE PARISH I COULD GO TO, THE BISHOP REPLIED …

Kierkegaard finally gave up all thoughts of being a church employee and branded the Christianity of Denmark as “Christendom” – a worldly, hierarchical and authoritative institution devoid of any true spirituality.

CHRISTENDOM, IN WHICH A NICE, GRUNTING, PROSPEROUS BOURGEOIS, PROVIDED THAT HE IS GENEROUS TO THE PASTOR, IS SUPPOSED TO BE THE EARNEST CHRISTIAN.

The Church was a “machine that just kept buzzing on”. If it were proved that Christ never actually existed, he said, how many good Christian churchmen would actually resign their posts?

Kierkegaard also wrote a series of fables in the manner of his old “Holy Alliance” friend, Hans Christian Andersen (1805–75), about the early Christian church, comparing it to the corrupt and tame institution that now went under its name.

A TAME GOOSE CAN NEVER BECOME A WILD GOOSE. BUT ON THE OTHER HAND, A WILD GOOSE CAN WELL BECOME A TAME GOOSE. So – BEWARE!

IT IS MY FATE TO BE TRAMPLED TO DEATH BY GEESE …