IN HIS OFFICE JUST off the Dynamo Room Admiral Ramsay listened politely as Captain Moulton described the desperate situation at Dunkirk, and the need for a greater naval effort if many men were to be saved. Moulton had the sinking feeling that he wasn’t getting his point across … that this was one of those cases where a mere Marine captain didn’t carry much weight with a Vice-Admiral of the Royal Navy.

His mission accomplished, Moulton returned to France, reported back to General Adam’s headquarters, and went to work on the beaches. Meanwhile, there were still few ships, but this wasn’t because Ramsay failed to appreciate the need. Relying mainly on personnel vessels—ferries, pleasure steamers, and the like—he had hoped to dispatch two every three and a half hours, but the schedule soon broke down.

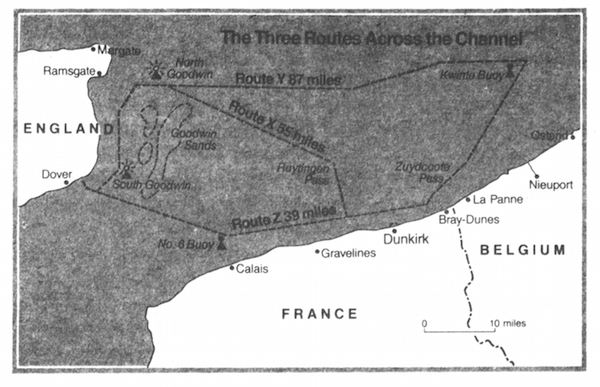

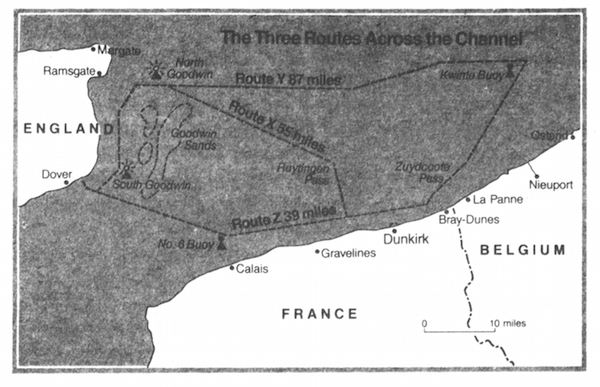

The first ship sent was Mono’s Isle, an Isle of Man packet. She left Dover at 9:00 p.m., May 26, and after an uneventful passage tied up at Dunkirk’s Gare Maritime around midnight. Packed with 1,420 troops, she began her return journey at sunrise on the 27th. Second Lieutenant D. C. Snowdon of the 1st/7th Queen’s Royal Regiment lay in exhausted sleep below decks, when he was suddenly awakened by what sounded like someone hammering on the hull. This turned out to be German artillery firing on the vessel. Because of shoals and minefields, the shortest route between Dunkirk and Dover (called Route Z) ran close to the shore for some miles west of Dunkirk. Passing ships offered a perfect target.

Several shells crashed into Mona’s Isle, miraculously without exploding. Then a hit aft blew away the rudder. Luckily, she was twin-screw, and managed to keep course by using her propellers. Gradually she drew out of range, and the troops settled down again. Lieutenant Snowdon went back to sleep below decks; others remained topside, soaking in the bright morning sun.

Then another rude awakening—this time by a sound like hail on the decks. Six Me 109’s were machine-gunning the ship. All the way aft Petty Officer Leonard B. Kearley-Pope crouched alone at the stern gun, gamely firing back. Four bullets tore into his right arm, but he kept shooting, until the planes broke off. Mona’s Isle finally limped into Dover around noon on the 27th with 23 killed and 60 wounded. Almost as bad from Ramsay’s point of view, the 40-mile trip had taken eleven and a half hours instead of the usual three.

By this time other ships too were getting a taste of those German guns. Two small coasters, Sequacity and Yewdale, had started for Dunkirk about 4:00 a.m. on the 27th. As they approached the French coast, a shell crashed into Sequacity’s starboard side at the waterline, continued through the ship and out the port side. Another smashed into the engine room, knocking out the pumps. Then two more hits, and Sequacity began to sink. Yewdale picked up the crew, and with shells splashing around her, headed back for England.

By 10:00 a.m. four more ships had been forced to turn back. None got through, and Admiral Ramsay’s schedule was in hopeless disarray. But he was a resourceful, resilient man; in the Dynamo Room the staff caught his spirit and set about revamping their plan.

Clearly Route Z could no longer be used, at least in daylight. There were two alternatives, neither very attractive. Route X, further to the northeast, would avoid the German batteries, but it was full of dangerous shoals and heavily mined. For the moment, at least, it too was out. Finally there was Route Y. It lay still further to the northeast, running almost as far as Ostend, where it doubled back west toward England. It was easier to navigate, relatively free of mines, and safe from German guns; but it was much, much longer—87 miles, compared to 55 for Route X and 39 for Route Z.

This meant the cross-Channel trip would be twice as long as planned; or, put another way, it would take twice as many ships to keep Ramsay’s schedule.

Still, it was the only hope, at least until Route X could be swept clear of mines. At 11:00 a.m. on the 27th the first convoy—two transports, two hospital ships, and two destroyers—left Dover and arrived off Dunkirk nearly six hours later.

The extra effort was largely wasted, for at the moment Dunkirk was taking such a pounding from the Luftwaffe that the port was practically paralyzed. The Royal Daffodil managed to pick up 900 men, but the rest of the convoy was warned to stay clear: too much danger of sinking and blocking the harbor. With that, the convoy turned and steamed back to Dover.

During the evening four more transports and two hospital ships arrived by Route Y. The transport Canterbury picked up 457 troops at the Gare Maritime, but then the Luftwaffe returned for a nighttime visit, and it again looked as though the harbor might be blocked.

As Canterbury pulled out, she received a signal from the shore to turn back any other vessels trying to enter. She relayed the message to several ships waiting outside, and they in turn relayed it to other ships. There was more than one inexperienced signalman at sea that night, and garbles were inevitable. By the time the warning was flashed by a passing ship to the skoot Tilly, coming over by Route Y, it said, “Dunkirk has fallen and is in enemy hands. Keep clear.”

Tilly was one of six skoots that had sailed together from the Dover Downs that afternoon. Her skipper, Lieutenant-Commander W.R.T. Clemments, had no idea why he was going to Dunkirk. His only clue was a pile of 450 lifejackets that had been dumped aboard just before sailing—rather many for a crew of eleven. Now here was a ship telling him to turn back from a trip he didn’t understand anyhow. After consulting with the nearest skoot, he put about and returned to Dover for further orders.

The other skoots hovered off Nieuport for a while. They too received signals from passing ships that Dunkirk had fallen. They too turned back. To cap off the day, two strings of lifeboats being towed over by a tug were run down and scattered.

This chain of mishaps and misunderstandings explained why the men waiting on the beaches saw so few ships on May 27. Only 7,669 men were evacuated that day, most of them “useless mouths” evacuated by ships sent from Dover before Dynamo officially began. At this rate it would take 40 days to lift the BEF.

As the bad news flowed in, Admiral Ramsay and his staff in the Dynamo Room struggled to get the show going again. Clearly more destroyers were needed—to escort the convoys, to fight off the Luftwaffe, to help lift the troops, to provide a protective screen for the longer Route Y. Ramsay fired off an urgent appeal to the Admiralty: take destroyers off other jobs; get them to Dunkirk. …

HMS Jaguar was on escort duty in the cold, foggy waters off Norway when orders came to return to England at once. … Havant was lying at Greenock, tucked among the green hills of western Scotland. … Harvester was a brand new destroyer training far to the south off the Dorset coast. One after another, all available destroyers were ordered to proceed to Dover “forthwith.”

Saladin was a 1914 antique on escort duty off the Western Approaches when she got the word. The other escort vessels had similar orders, and all complied at once. The twelve to fourteen ships in the convoy were left to fend for themselves. These were dangerous waters, and Chief Signal Clerk J. W. Martin of the Saladin wondered what the commodore of the convoy thought as he watched his protection steam away.

On the destroyers few of the men knew what was up. On the Saladin Martin, who saw much of the message traffic, caught a reference to “Dynamo,” but that told him nothing. He just knew it must be important if they were leaving a convoy in this part of the Atlantic.

Speculation increased as the destroyers reached Dover and were ordered to proceed immediately to “beaches east of Dunkirk.” On the Malcolm the navigation officer, Lieutenant David Mellis, supposed they were going to bring off some army unit that had been cut off. With luck they should finish the job in a few hours. The Anthony passed a motor boat heading back to England with about twenty soldiers aboard. The officer of the watch shouted across the water, asking if there were many more to come. “Bloody thousands,” somebody yelled back.

It was still dark when the Jaguar crept near the French coast in the early hours of May 28. As dawn broke, Stoker A. D. Saunders saw that the ship was edging toward a beautiful stretch of white sand, which appeared to have shrubs planted all over it. Then the shrubs began to move, forming lines pointed toward the sea, and Saunders realized they were men, thousands of soldiers waiting for help.

The whole stretch of beach from Dunkirk to La Panne shelved so gradually that the destroyers couldn’t get closer than a mile, even at high tide. Since no small craft were yet on the scene, the destroyers had to use their own boats to pick up the men. The boat crews weren’t used to this sort of work, the soldiers even less so.

Sometimes they piled into one side all at once, upsetting the craft. Other times too many crowded into a boat, grounding or swamping it. All too often they simply abandoned the boat once they reached the rescue ship. Motors were clogged with sand, propellers fouled by debris, oars lost. Operating off Malo-les-Bains in the early hours of May 28, Sabre’s three boats picked up only 100 men in two hours. At La Panne, Malcolm’s record was even worse—450 men in fifteen hours.

“Plenty troops, few boats,” the destroyer Wakeful radioed Ramsay at 5:07 a.m. on the 28th, putting the problem as succinctly as possible. All through the day Wakeful and the other destroyers sent a stream of messages to Dover urging more small boats. The Dynamo Room in turn needled London.

The Small Vessels Pool was doing its best, but it took time to wade through the registration data sent in by owners. Then H. C. Riggs of the Ministry of Shipping thought of a short-cut. Why not go direct to the various boatyards along the Thames? With a war on, many of the owners had laid up their craft.

At Tough Brothers boatyard in Teddington the proprietor, Douglas Tough, got an early-morning phone call from Admiral Sir Lionel Preston himself. The evacuation was still secret, but Preston took Tough into his confidence, explaining the nature of the problem and the kind of boats needed.

The Admiral couldn’t have come to a better man. The Tough family had been in business on the Thames for three generations. Douglas Tough had founded the present yard in 1922 and knew just about every boat on the river. He was willing to act for the Admiralty, commandeering any suitable craft.

The first fourteen were already in the yard. Supervised by Chief Foreman Harry Day, workmen swiftly off-loaded cushions and china, ripped out the peacetime fittings, put the engines in working order, filled the fuel tanks.

Tough himself went up and down the river, picking out additional boats that he thought could stand the wear and tear of the job ahead. Most owners were willing; some came along with their boats. A few objected, but he commandeered their vessels anyhow. Some never realized what was happening, until they later found their boats missing and reported the “theft” to the police.

Meanwhile volunteer crews were also being assembled at Tough’s, mostly amateurs from organizations like the Little Ships Club or a wartime creation called the River Emergency Service. These gentleman sailors would get the boats down the river to Southend, where the Navy would presumably take over.

The Small Vessels Pool, of course, did not confine its efforts to Tough’s. It tried practically every boatyard and yacht club from Cowes to Margate. Usually no explanation was given—just the distance the boats had to go. At William Osborne’s yard in Littlehampton the cabin cruisers Gwen Eagle and Bengeo seemed to fill the bill; local hands were quickly rounded up by the harbor master, and off they went.

Often the Small Vessels Pool dealt directly with the owners in its files. Technically every vessel was chartered, but the paperwork was usually done long afterwards.

Despite a later legend of heroic sacrifice, some cases were difficult. Preston’s assistant secretary Stanley Berry found himself dealing interminably with the executor of a deceased owner’s estate, who wanted to know who was going to pay a charge of £3 for putting the boat in the water. But most were like the owner who asked whether he could retrieve some whisky left on board. When Berry replied it was too late for that, the man simply said he hoped the finder would have a good drink on him.

By now the Dynamo Room was reaching far beyond the Small Vessels Pool. The Nore Command of the Royal Navy, based at Chatham, scoured the Thames estuary for shallow-draft barges. The Port of London authorities stripped the lifeboats off the Volendam, Durbar Castle, and other ocean liners that happened to be in dock. The Royal National Lifeboat Institution sent everything it had along the east and south coasts.

The Army offered eight landing craft (called ALC’s), but some way had to be found to bring them from Southampton. Jimmy Keith, the Ministry of Shipping liaison man in the Dynamo Room, phoned Basil Bellamy at the Sea Transport Division in London. For once, the solution was easy. Bellamy flipped through his cards and found that the cargo liner Clan MacAlister, already in Southampton, had exceptionally strong derrick posts. She began loading the ALC’s on the morning of the 27th, and was on her way down the Solent by 6:30 p.m.

On board was a special party of 45 seamen and two reserve officers. They would man the ALC’s. Like the crews for the skoots, they were drawn from the Chatham Naval Barracks. Sometimes a ship was lucky and drew an experienced crew. More often it was like the skoot Patria, which had a coxswain who couldn’t steer and an engineer making his first acquaintance with marine diesels.

In the Dynamo Room, Admiral Ramsay’s staff worked on. There seemed a million things to do, and all had to be done at once: Clear Route X of mines. … Get more fighter cover from the RAF. … Find more Lewis guns. … Dispatch the antiaircraft cruiser Calcutta to the scene. … Repair damaged vessels. … Replace worn-out crews. … Send over water for the beleaguered troops. … Prepare for the wounded. … Get the latest weather forecast. … Line up some 125 maintenance craft to service the little ships now gathering at Sheerness. … Put some men to work making ladders—fast.

“Poor Morgan,” Ramsay wrote Mag, describing the effect on his staff, “is terribly strained and badly needs a rest. ‘Flags’ looks like a ghost, and the Secretary has suddenly become old. All my staff are in fact completely worn out, yet I see no prospect of any let up. …”

For Ramsay himself there was one ray of light. Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville had come down from London, volunteering to take over from time to time so that Ramsay could get a bit of rest. Somerville had an electric personality, and was worshiped by junior officers. He was not only a perfect stand-in but a good trouble-shooter as well. Shortly after his arrival on May 27 morale collapsed on the destroyer Verity. She had been badly shelled on a couple of trips across the Channel, her captain was seriously wounded, and the crew had reached the breaking point. One sailor even tried to commit suicide. When the acting skipper reported the situation to Dover Castle, Somerville went back with him and addressed the ship’s company. Knowing that words can only accomplish so much, he also rested Verity overnight. Next morning she was back on the job.

To Somerville, to Ramsay—to the whole Dynamo Room contingent—the evacuation had become an obsession. So it seemed like a visit from another world when three high-ranking French naval officers turned up in Dover on the 27th to discuss, among other things, how to keep Dunkirk supplied.

From General Weygand on down, the French still regarded the port as a permanent foothold on the Continent. Admiral Darlan, the suave naval Chief of Staff, was no exception, and his deputy, Captain Paul Auphan, had the task of organizing a supply fleet for the beachhead. Auphan decided that trawlers and fishing smacks were the best bet, and his men fanned out over Normandy and Brittany commandeering more than 200 vessels.

Meanwhile, disturbing news reached Darlan. A liaison officer attached to Gort’s headquarters reported that the British were considering evacuation—with or without the French. It was decided to send Auphan to Dover, where he would be joined by Rear-Admiral Marcel Leclerc from Dunkirk and by Vice-Admiral Jean Odend’hal, head of the French Naval Mission in London. A firsthand assessment might clarify the situation.

Auphan and Odend’hal arrived first, and as they waited for Leclerc in the officers’ mess, Odend’hal noticed a number of familiar British faces. They were strictly “desk types”—men he saw daily at the Admiralty—yet here they were in Dover wearing tin hats. Odend’hal asked what was up. “We're here for the evacuation,” they replied.

The two visitors were astonished. This was the first word to reach the French Navy that the British were not merely “considering” evacuation—they were already pulling out. Leclerc now arrived, and all three went to see Ramsay. He brought them up to date on Dynamo. Auphan began rearranging the plans for his fleet of fishing smacks and trawlers. Instead of supplying the beachhead, they would now be used to evacuate French troops. The two navies would work together, but it was understood that each country would look primarily after its own.

Back in France next day, the 28th, Auphan rushed to French naval headquarters at Maintenon and broke the news to Darlan. The Admiral was so amazed he took the Captain to see General Weygand. He professed to be equally surprised, and Auphan found himself in the odd position of briefing the Supreme Allied Commander on what the British were doing.

It’s hard to understand why they all were so astounded. On the afternoon of May 26 Churchill told Reynaud that the British planned to evacuate, urging the French Premier to issue “corresponding orders.” At 5:00 a.m. on the 27th Eden radioed the British liaison at Weygand’s headquarters, asking where the French wanted the evacuated troops to be landed when they returned to that part of France still held by the Allies. At 7:30 a.m. the same day the French and British commanders meeting at Cassel discussed the “lay-out of the beaches” at Dunkirk—they could only have been talking about the evacuation.

Informally, the French had been aware of Gort’s thinking a good deal sooner. As early as May 23 a British liaison officer, Major O. A. Archdale, came unofficially to say good-bye to his opposite number, Major Joseph Fauvelle, at French First Army Group headquarters. Fauvelle gathered that evacuation was in the wind and told his boss, General Blanchard. He in turn sent Fauvelle to Paris to tell Weygand. The information was in the Supreme Commander’s hands by 9:00 a.m., May 25.

And yet, surprise and confusion on the 28th, when Captain Auphan reported that the British had begun to evacuate. Perhaps the best explanation lies in the almost complete breakdown of French communications. The troops trapped in Flanders were no longer in touch with Weygand’s headquarters, except by wireless via the French Navy, and their headquarters at Maintenon was 70 miles from Paris.

As a result, vital messages were delayed or missed altogether. The various commands operated in a vacuum; there was no agreement on policy or tactics even among themselves. Reynaud accepted evacuation. Weygand thought in terms of a big bridgehead including a recaptured Calais. Blanchard and Fagalde wrote off Calais, but still planned on a smaller bridgehead built around Dunkirk. General Prioux, commanding First Army, was bent on a gallant last stand down around Lille.

In contrast, the British were now united in one goal—evacuation. As Odend’hal noted, even senior staff officers from the Admiralty were manning small boats and working the beaches—often on the shortest notice.

One of these was Captain William G. Tennant, a lean, reserved navigation expert who normally was Chief Staff Officer to the First Sea Lord in London. He got his orders on May 26 at 6:00 p.m.; by 8:25 he was on the train heading for Dover. Tennant was to be Senior Naval Officer at Dunkirk, in charge of the shore end of the evacuation. As SNO he would supervise the distribution and loading of the rescue fleet. To back him up he had a naval shore party of eight officers and 160 men.

After a brief stopover at Chatham Naval Barracks, he arrived in Dover at 9:00 a.m. on the 27th. Meanwhile buses were coming from Chatham, bringing the men assigned to the shore party. Most still had no idea what was up. One rumor spread that they were going to man some six-inch guns on the Dover cliffs. Seaman Carl Fletcher was delighted at the prospect: he then would be stationed near home.

He soon learned better. On arrival at Dover the men were divided into parties of twenty, each commanded by one of Tennant’s eight officers. Fletcher’s group was under Commander Hector Richardson, who explained that they would shortly be going to Dunkirk. It was a bit “hot” there, he added, and they might like to fortify themselves at a pub across the way. To a man they complied, and Seaman Fletcher belted down an extra one for the trip over.

The destroyer Wolfhound would be taking them across, and shortly before departure her skipper, Lieutenant-Commander John McCoy, dropped by the wardroom to learn what his officers knew about conditions at Dunkirk. Sub-Lieutenant H. W. Stowell piped up that he had a friend on another destroyer who was there recently and had a whale of a time—champagne, dancing girls, a most hospitable port.

At 1:45 p.m. Wolfhound sailed, going by the long Route Y. At 2:45 the first Stukas struck, and it was hell the rest of the way. Miraculously, the ship dodged everything, and at 5:35 slipped into Dunkirk harbor. The whole coastline seemed ablaze, and a formation of 21 German planes rained bombs on the quay as Wolfhound tied up. Commander McCoy dryly asked Sub-Lieutenant Stowell where the champagne and dancing girls were.

The Wolfhound was too inviting a target. Captain Tennant landed his shore party and dispersed them as soon as possible. Then he set off with several of his officers for Bastion 32, where Admiral Abrial had allotted space to the local British command.

Normally it was a ten-minute walk, but not today. Tennant’s party had to pick their way through streets littered with rubble and broken glass. Burned-out trucks and tangled trolley wires were everywhere. Black, oily smoke swirled about the men as they trudged along. Dead and wounded British soldiers sprawled among the debris; others, perfectly fit, prowled aimlessly about, or scrounged among the ruins.

It was well after 6:00 p.m. by the time they reached Bastion 32, which turned out to be a concrete bunker protected by earth and heavy steel doors. Inside, a damp, dark corridor led through a candle-lit operations room to the cubbyhole that was assigned to the British Naval Liaison Officer, Commander Harold Henderson.

Here Tennant met with Henderson, Brigadier R.H.R. Parminter from Gort’s staff, and Colonel G.H.P. Whitfield, the Area Commandant. All three agreed that Dunkirk harbor couldn’t be used for evacuation. The air attacks were too devastating. The beaches to the east were the only hope.

Tennant asked how long he would have for the job. The answer was not encouraging: “24 to 36 hours.” After that, the Germans would probably be in Dunkirk. With this gloomy assessment, at 7:58 p.m. he sent his first signal to Dover as Senior Naval Officer:

Please send every available craft East of Dunkirk immediately. Evacuation tomorrow night is problematical.

At 8:05 he sent another message, elaborating slightly:

Port continually bombed all day and on fire. Embarkation possible only from beaches east of harbour. … Send all ships and passenger ships there. Am ordering Wolfhound to anchor there, load and sail.

In Dover, the Dynamo Room burst into action as the staff rushed to divert the rescue fleet from Dunkirk to the ten-mile stretch of sand east of the port. …

9:01, Maid of Orleans not to enter Dunkirk but anchor close inshore between Malo-les-Bains and Zuydcoote to embark troops from beach. …

9:27, Grafton and Polish destroyer Blyskawicz to close beach at La Panne at 0100/28 and embark all possible British troops in own boats. This is our last chance of saving them. …

9:42, Gallant [plus five other destroyers and cruiser Calcutta] to close beach one to three miles east of Dunkirk with utmost despatch and embark all possible British troops. This is our last chance of saving them.

Within an hour the Dynamo Room managed to shift to the beaches all the vessels in service at the moment: a cruiser, 9 destroyers, 2 transports, 4 minesweepers, 4 skoots, and 17 drifters—37 ships altogether.

In Dunkirk, Captain Tennant’s naval party went to work rounding up the scattered troops and sending them to the nearest beach at Malo-les-Bains. Here they were divided by Commander Richardson into packets of 30 to 50 men. In most cases the soldiers were pathetically eager to obey anybody who seemed to know what he was doing. “Thank God we’ve got a Navy,” remarked one soldier to Seaman Fletcher.

Most of the troops were found crowded in the port’s cellars, taking cover from the bombs. Second Lieutenant Arthur Rhodes managed to get his men into a basement liberally stocked with champagne and foie gras, which became their staple diet for some time. But this did not mean they were enjoying the good life. Some 60 men, two civilian women, and assorted stray dogs were packed in together. The atmosphere was heavy … made even heavier when one of the soldiers fed some foie gras to one of the dogs, and it promptly threw up.

Some of the men took to the champagne, and drunken shouts soon mingled with the crash of bombs and falling masonry that came from above. From time to time Rhodes ventured outside trying to find a better cellar, but they all were crowded and he finally gave up. Toward evening he heard a cry for “officers.” Going up, he learned that the Royal Navy had arrived. He was to take his men to the beaches; ships would try to lift them that night.

Cellars couldn’t hold all the men now pouring into Dunkirk. Some, looking desperately for cover, headed for the sturdy old French fortifications that lay between the harbor and the beaches east of town. Bastion 32 was here, with its small quota of British staff officers, but the French units holed up in the area were not inclined to admit any more visitors.

Terrified and leaderless, one group of British stragglers wasn’t about to turn back. They had no officers, but they did have rifles. During the evening of the 27th they approached Bastion 32, brandishing their guns and demanding to be let in. Two Royal Navy officers came out unarmed and parlayed with them. It was still touch and go when one of Tennant’s shore parties arrived. The sailors quickly restored order, and this particular crisis was over.

Seaman G. F. Nixon, attached to one of these naval parties, later recalled how quickly the troops responded to almost any show of firm authority. “It was amazing what a two-badge sailor with a fixed bayonet and a loud voice did to those lads.”

Captain Tennant, making his first inspection of the beaches as SNO, personally addressed several jittery groups. He urged them to keep calm and stay under cover as much as possible. He assured them that plenty of ships were coming, and that they would all get safely back to England.

He was invariably successful, partly because the ordinary Tommy had such blind faith in the Royal Navy, but also because Tennant looked like an officer. Owing to the modern fashion of dressing all soldiers alike, the army officers didn’t stand out even when present, but there was no doubt about Tennant. In his well-cut navy blues, with its brass buttons and four gold stripes, he had authority written all over him.

And in Tennant’s case, there was an extra touch. During a snack at Bastion 32 his signal officer, Commander Michael Ellwood, cut the letters “S-N-O” from the silver foil of a cigarette pack, then glued them to the Captain’s helmet with thick pea soup.

Unfortunately no amount of discipline could change the basic arithmetic of Dunkirk. Far too few men were being lifted from the beaches. Tennant estimated he could do the job five or six times faster if he could use the docks. Yet one glance at Dunkirk’s blazing waterfront proved that was out of the question.

But he did notice a peculiar thing. Although the Luftwaffe was pounding the piers and quays, it completely ignored the two long breakwaters or moles that formed the entrance to Dunkirk’s harbor. Like a pair of protective arms, these moles ran toward each other—one from the west and one from the east—with just enough room for a ship to pass in between. It was the eastern mole that attracted Tennant’s special attention. Made of concrete piling topped by a wooden walkway, it ran some 1,400 yards out to sea. If ships could be brought alongside, it would speed up the evacuation enormously.

The big drawback: the mole was never built to be used as a pier. Could it take the pounding it would get, as the swift tidal current—running as high as three knots—slammed ships against the flimsy wooden planking? There were posts here and there, but they were meant only for occasional harbor craft. Could large vessels tie up without yanking the posts loose? The walkway was just ten feet wide, barely room for four men walking abreast. Would this lead to impossible traffic jams?

All these difficulties were aggravated by a fifteen-foot tidal drop. Transferring the troops at low or high water was bound to be a tricky and dangerous business.

Still, it was the only hope. At 10:30 p.m. Tennant signaled Wolfhound, now handling communications offshore, to send a personnel ship to the mole “to embark 1,000 men.” The assignment went to Queen of the Channel, formerly a crack steamer on the cross-Channel run. At the moment she was lifting troops from the beach at Malo-les-Bains, and like everyone else, her crew found it slow going. She quickly shifted to the mole and began loading up. She had no trouble, and the anxious naval party heaved a collective sigh of relief.

By 4:15 a.m. some 950 men crammed the Queen’s decks. Dawn was breaking, when a voice called out from the mole asking how many more she could take. “It’s not a case of how many more,” her skipper shouted back, “but whether we can get away with what we already have.”

He was right. Less than halfway across the Channel a single German plane dropped a stick of bombs just astern of the Queen, breaking her back. Except for a few soldiers who jumped overboard, everyone behaved with amazing calm. Seaman George Bartlett even considered briefly whether he should go below for a new pair of shoes he had left in his locker. He wisely thought better of it, for the ship was now sinking fast. He and the rest stood quietly on the sloping decks, until a rescue ship, the Dorrien Rose, nudged alongside and transferred them all.

The Queen of the Channel was lost, but the day was saved. The mole worked! The timbers did not collapse; the tide did not interfere; the troops did not panic. There was plenty of room for a steady procession of ships. The story might be different once the Germans caught on, but clouds of smoke hung low over the harbor. Visibility was at a minimum.

“SNO requires all vessels alongside east pier,” the destroyer Wakeful radioed Ramsay from Dunkirk at 4:36 a.m. on the 28th. Once again the staff in the Dynamo Room swung into action. They had spent the early part of the night diverting the rescue fleet from the harbor to the beaches; now they went to work shifting it back again. On the beach at Malo-les-Bains Commander Richardson got the word too and began sending the troops back to Dunkirk in batches of 500.

But even as the loading problem was being solved, a whole new crisis arose. Critical moments at Dunkirk had a way of alternating between the sea and the land, and this time, appropriately enough, the setting once again reverted to the battle-scarred fields of Flanders.

At 4 a.m.—just as the Queen of the Channel was proving that the mole would work—Leopold III, King of the Belgians, formally laid down his arms. The result left a twenty-mile gap in the eastern wall of the escape corridor. Unless it could be closed at once, the Germans would pour in, cut the French and British off from the sea, and put an abrupt end to the evacuation.