Plunging down from the sky, a German Stuka dive-bombs an Allied tank, as Hitler strikes west in May 1940. Together with the armored panzer division, the Stuka symbolized a new kind of lightning war—the Blitzkrieg—which the Allies were utterly unprepared to meet. German columns knifed through to the sea, trapping the British and French against the coast of Flanders. (Hergestellt im Bundesarchiv Bestand)

On the receiving end of the German onslaught were the Allied commanders, British General the Viscount Gort (left) and French General Maurice Gamelin. Within days Gamelin was fired and Gort was reeling back toward the French port of Dunkirk. Below, a file of British troops straggles into Dunkirk, hoping to escape by sea. (Top: Wide World Photos. Bottom: Hergestellt im Bundesarchiv Bestand)

Thousands of Allied soldiers soon crowded the beaches that stretched from Dunkirk to La Panne, a small Belgian resort ten miles to the east. Long lines of men curled out into the sea, patiently waiting to be picked up. (Times)

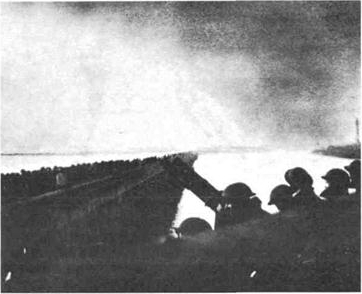

As the troops waited, German planes continued to pound them. For protection they dug foxholes in the dunes. Casualties were surprisingly light, since the sand tended to smother the exploding bombs. (Imperial War Museum)

Across the English Channel, a giant rescue operation was hastily organized under the command of Vice-Admiral Bertram H. Ramsay. Here Admiral Ramsay briefly relaxes on the balcony of his headquarters, carved out of the famous chalk cliffs of Dover. (Courtesy of Jane Evan-Thomas)

Command center for the evacuation was the austere “Dynamo Room,” buried deep in the Dover cliffs. Here Ramsay’s staff, using a battery of telephones, assembled and deployed a rescue fleet that ultimately totaled 861 ships. This photo is believed to be the only picture ever taken of the room. (Courtesy of W. J. Matthews)

Every kind of vessel was used for the evacuation, ranging from warships to small pleasure craft. Above, a “G” Class destroyer races toward Dunkirk “with a bone in her teeth.” This entire class was eventually knocked out. Below, the yacht Sundowner was luckier. She rescued 135 men and escaped without a scratch. Her owner-skipper, Commander C. H. Lightoller, had performed earlier heroics as Second Officer on the Titanic.(Top: Imperial War Museum. Bottom: courtesy of Patrick Stenson and Sharon Rutman)

Dunkirk was easy to find. A huge pall of smoke from burning oil tanks hung over the shattered port. The smoke seemed to symbolize defeat and disaster, but had the happy side effect of concealing the harbor from German bombers. (Courtesy of W. J. Matthews)

In contrast, La Panne, at the eastern end of the evacuation area, looked deceptively tranquil. Rescue ships can be seen here, picking up troops near the shore. Gort’s headquarters was in one of the detached houses on the far right. (Courtesy of J. L. Aldridge)

Picking up troops direct from the beach seemed to take forever—“loading ships by the spoonful” was the way one embarkation officer described it. Above, a trawler and a coaster take aboard men wading out from the shore. At right, British Tommies are up to their shoulders in water, approaching a rescue ship. (Top: Wide World Photos. Bottom: The Granger Collection)

Captain William G. Tennant (left) was finally appointed by Admiral Ramsay to take charge at Dunkirk and speed up the evacuation. As Senior Naval Officer (SNO), Tennant discovered that the eastern mole of Dunkirk harbor was ideal for loading ships. Here a destroyer could lift 600 men in 20 minutes, while it took 12 hours along the beaches. For most of the next week the mole was packed with an endless line of troops (below) trudging out to the waiting ships. (Top: ILN Pic Lib. Bottom: Times)

Ingenuity triumphed on the beaches too. Abandoned lorries were strung together, to form improvised piers leading out into the water. Here one of these “lorry jetties” is visible in the background. (Courtesy of D.C.H. Shields)

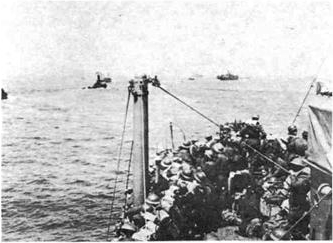

Soon an unbroken line of crowded ships could be seen carrying the men across the Channel to safety. (Culver Pictures)

The Luftwaffe did not leave the rescue fleet alone. These two pictures show how suddenly disaster could strike. In the top photo an Allied ship has just blown up, while two others lie nearby still untouched. In the bottom photo, taken an instant later (note that the configuration of smoke is still the same), the two nearby ships have now disappeared, obliterated by the rain of bombs. Troops on the beach are futilely firing their rifles at the planes. (Top: Imperial War Museum. Bottom: Fox Photos Ltd.)

The French destroyer Bourrasque joins the growing list of Allied casualties. Packed with troops, she struck a German mine and went down with a loss of 150 lives. (Imperial War Museum)

A fleet of French fishing trawlers was a late addition to Ramsay’s armada. They concentrated on the inner harbor of Dunkirk, where hundreds of poilus swarmed aboard. (Wide World Photos)

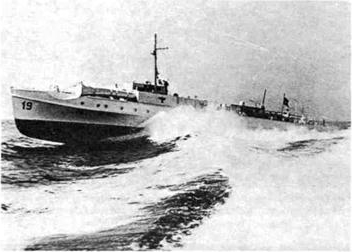

Bombs and mines were not the only perils faced by the rescue fleet. The Schnellboote, fast German motor torpedo boats, prowled the seas at night, sinking and damaging Ramsay’s ships. (Hergestellt im Bundesarchiv Bestand)

German artillery added to the toll. Nothing was safe—neither the ships, the harbor, the mole, nor the men on the beaches. “Greetings to Tommy” is the message painted on this shell. (Hergestellt im Bundesarchiv Bestand)

German troops finally broke into La Panne on June 1 and began moving down the beach toward Dunkirk itself. Below, the fall of Dunkirk, June 4, Weary but triumphant, German troops of the 18th Infantry Division stack their arms and rest. (Hergestellt im Bundesarchiv Bestand)

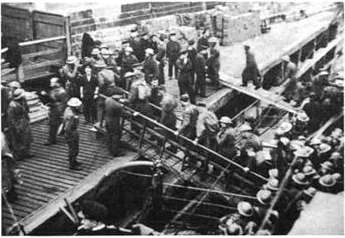

The quarry was gone. In nine desperate days Ramsay’s fleet brought back more than 338,000 Allied troops. Typical was this batch, disembarking from the minesweeper Sandown. Naval officer in the lower-left foreground is Lieutenant Wallis, the ship’s First Lieutenant. (Courtesy of J. D. Nunn)

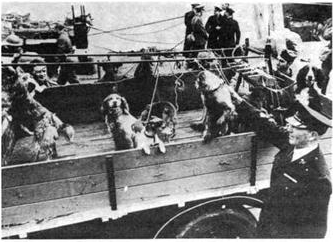

Sometimes it seemed as if half the canine population of France had been evacuated too. Never was the Englishman’s legendary fondness for dogs more ringingly affirmed. At least 170 dogs were landed in Dover alone. (Wide World Photos)

Disheveled but happy, the Tommies were sent by train to assembly areas all over Britain for rest and reorganization. At every station a relieved populace showered them with cigarettes, cakes, candy, and affection. (Wide World Photos)

At Dunkirk, the captured French rear guard heard no cheers. They would soon be marching off to POW camp, most for the duration of the war. (Hergestellt im Bundesarchiv Bestand)

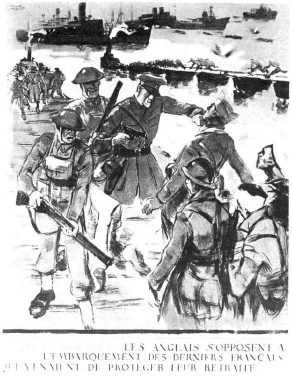

In another two weeks France was knocked out of the war. The new pro-German Vichy government lost no time charging that the British had run out, leaving the French holding the bag at Dunkirk. Actually, Ramsay’s rescue fleet saved over 123,000 French soldiers, 102,570 in British ships. Despite the statistics, French bitterness continues, even today. (Musée des Deux Guerres Mondiales—B.D.I.C., Universités de Paris)