EVERY MAN HAD HIS own special moment when he first knew that something was wrong. For RAF Group Captain R.C.M. Collard, it was the evening of May 14, 1940, in the market town of Vervins in northeastern France.

Five days had passed since “the balloon went up,” as the British liked to refer to the sudden German assault in the west. The situation was obscure, and Collard had come down from British General Headquarters in Arras to confer with the staff of General André-Georges Corap, whose French Ninth Army was holding the River Meuse to the south.

Such meetings were perfectly normal between the two Allies, but there was nothing normal about the scene tonight. Corap’s headquarters had simply vanished. No sign of the General or his staff. Only two exhausted French officers were in the building, crouched over a hurricane lamp … waiting, they said, to be captured.

Sapper E. N. Grimmer’s moment of awareness came as the 216th Field Company, Royal Engineers, tramped across the French countryside, presumably toward the front. Then he noticed a bridge being prepared for demolition. “When you’re advancing,” he mused, “you don’t blow bridges.” Lance Corporal E. S. Wright had a ruder awakening: he had gone to Arras to collect his wireless unit’s weekly mail. A motorcycle with sidecar whizzed past, and Wright did a classic double take. He suddenly realized the motorcycle was German.

For Winston Churchill, the new British Prime Minister, the moment was 7:30 a.m., May 15, as he lay sleeping in his quarters at Admiralty House, London. The bedside phone rang; it was French Premier Paul Reynaud. “We have been defeated,” Reynaud blurted in English.

A nonplussed silence, as Churchill tried to collect himself.

“We are beaten”; Reynaud went on, “we have lost the battle.”

“Surely it can’t have happened so soon?” Churchill finally managed to say.

“The front is broken near Sedan; they are pouring through in great numbers with tanks and armored cars.”

Churchill did his best to soothe the man—reminded him of the dark days in 1918 when all turned out well in the end—but Reynaud remained distraught. He ended as he had begun: “We are defeated; we have lost the battle.”

The crisis was so grave—and so little could be grasped over the phone—that on the 16th Churchill flew to Paris to see things for himself. At the Quai d’Orsay he found “utter dejection” on every face; in the garden elderly clerks were already burning the files.

It seemed incredible. Since 1918 the French Army had been generally regarded as the finest in the world. With the rearmament of Germany under Adolf Hitler, there was obviously a new military power in Europe, but still, her leaders were untested and her weapons smacked of gimmickry. When the Third Reich swallowed one Central European country after another, this was attributed to bluff and bluster. When war finally did break out in 1939 and Poland fell in three weeks, this was written off as something that could happen to Poles—but not to the West. When Denmark and Norway went in April 1940, this seemed just an underhanded trick; it could be rectified later.

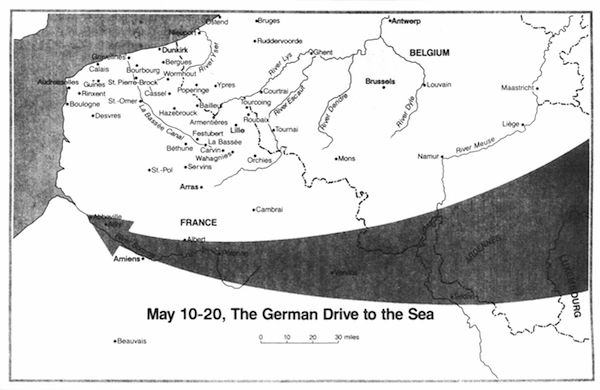

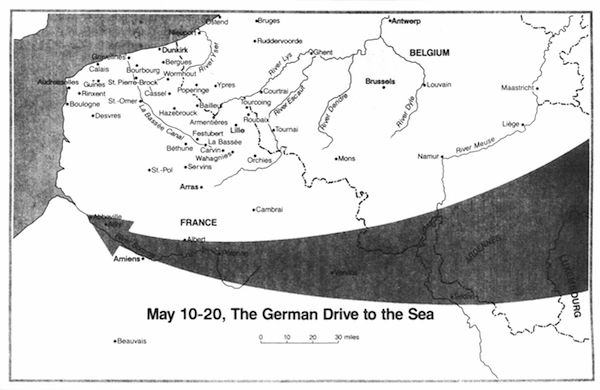

Then after eight months of quiet—“the phony war”—on the 10th of May, Hitler suddenly struck at Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Convinced that the attack was a replay of 1914, the Supreme Allied Commander, General Maurice Gamelin, rushed his northern armies—including the British Expeditionary Force—to the rescue.

But Gamelin had miscalculated. It was not 1914 all over again. Instead of a great sweep through Flanders, the main German thrust was farther south, through the “impenetrable” Ardennes Forest. This was said to be poor tank country, and the French hadn’t even bothered to extend the supposedly impenetrable Maginot Line to cover it.

Another miscalculation. While General Colonel Fedor von Bock’s Army Group B tied up the Allies in Belgium, General Colonel Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group A came crashing through the Ardennes. Spearheaded by 1,806 tanks and supported by 325 Stuka dive bombers, Rundstedt’s columns stormed across the River Meuse and now were knifing through the French countryside.

General Corap’s Ninth Army was the luckless force that took the brunt. Composed mainly of second-class troops, it quickly collapsed. Here and there die-hard units tried to make a stand, only to discover that their antitank guns were worthless. One junior officer ended up at the Le Mans railroad station, where he committed suicide after penning a postcard to Premier Reynaud: “I am killing myself, Mr. President, to let you know that all my men were brave, but one cannot send men to fight tanks with rifles.”

It was the same story with part of General Charles Huntziger’s Second Army at Sedan, fifty miles farther south. As the German tanks approached, the men of the 71st Division turned their helmets around—a rallying sign of the Communists—and bolted for the rear.

Three brigades of French tanks tried to stem the tide, but never had a chance. One brigade ran out of gas; another was caught de-training in a railroad yard; the third was sprinkled in small packets along the front, where it was gobbled up piecemeal.

Now the panzers were in the clear—nothing to stop them. Shortly after 7:00 a.m., May 20, two divisions of General Heinz Guderian’s crack XIX Corps began rolling west from Péronne. By 10:00 they were clanking through the town of Albert, where a party of untrained English Territorials tried to hold them with a barricade of cardboard boxes. … 11:00, they reached Hédauville, where they captured a British battery equipped with only training shells … noon, the 1st Panzer Division had Amiens, where Guderian took a moment to savor the towers of the lovely cathedral.

The 2nd Panzer Division rolled on. By 4:00 p.m. they had Beauquesne, where they captured a depot containing the BEF’s entire supply of maps. And finally, at 9:10, they reached Abbeville and then the sea. In one massive stroke they had come 40 miles in fourteen hours, cutting the Allied forces in two. The BEF, two French armies, and all the Belgians—nearly a million men—were now sealed in Flanders, pinned against the sea, ready for plucking.

Deep in Belgium the British front-line troops had no way of knowing what had happened on their flank or to the rear. They only knew that they were successfully holding the Germans facing them on the River Dyle. On May 14 (the day Rundstedt routed Corap), Lance Bombardier Noel Watkin of the Royal Artillery heard rumors of a great Allied victory. That night he had nothing but good news for the diary he surreptitiously kept:

Enemy retreat 6 ½ miles. Very little doing till the evening. We fire on S.O.S. lines and prevent the Huns crossing the River Dyle. Many Germans are killed and taken prisoner. 27,000 Germans killed (official).

Next day was different. As the French collapsed to the south, the Germans surged into the gap. Soon shells were unaccountably pouring into the British flank. That evening a bewildered Noel Watkin could only write:

What a day! We are due to retreat at 10:30 p.m., and as we do, we get heavy shellfire, and we thank God we are all safe. … Except for the shock I am o.k.

Most of the BEF were equally mystified by the sudden change in fortune. Throughout the 16th and 17th, the troops began to pull back all along the line; more and more guns were shifted to face south and southwest. On the 18th, when the 2nd Essex was ordered to man the La Bassée Canal, facing south, the battalion commander Major Wilson was incredulous—wasn’t the enemy supposed to be to the east? “I can’t understand it, sir,” agreed Captain Long Price, just back from brigade headquarters, “but those are our orders.”

One man who could understand it very well was the architect of these stop-gap measures: General the Viscount Gort, Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force. A big burly man of 53, Lord Gort was no strategist—he was happy to follow the French lead on such matters—but he had certain soldierly virtues that came in handy at a time like this. He was a great fighter—had won the Victoria Cross storming the Hindenburg Line in 1918—and he was completely unflappable.

General Alphonse-Joseph Georges, his French superior, might be in tears by now, but never Gort. He methodically turned to the job of protecting his exposed flank and pulling his army back. His trained combat divisions were tied up fighting the Germans to the east. To meet the new threat to the south and the west, he improvised a series of scratch forces, composed of miscellaneous units borrowed from here and there. Gort appointed his intelligence chief, Major-General Noel Mason-MacFarlane, as the commander of one of these groups, appropriately called MACFORCE. Mason-MacFarlane was an able leader, but the main effect of his assignment was to raise havoc with the intelligence set-up at GHQ in Arras. That didn’t seem to bother Gort; always the fighting man, he had little use for staff officers anyway.

Meanwhile, using a timetable worked out by the French, on the evening of May 16 he began pulling his front-line troops back from the Dyle. The new line was to be the River Escaut,* 60 miles to the rear, the retreat to be carried out in three stages.

Crack units like the 2nd Coldstream Guards carried out their orders meticulously—generations of tradition saw to that. For others, these instructions—so precise on paper—didn’t necessarily work out in fact. Dispatch riders carrying the orders couldn’t always find the right headquarters. Some regiments started late. Others lost their way in the dark. Others made the wrong turn. Others ran into hopeless traffic jams. Still others never got the orders at all.

The 32nd Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, was hurrying toward the Dyle, unaware of any retreat, when word came to take position in a field some miles short of the river. Gunner R. Shattock was told to take one of the unit’s trucks and get some rations. This he did, but by the time he got back, the whole regiment had vanished. After a night of worry, he set out for the main road, hoping to find at least a trace of somebody he knew.

He was immediately swamped by a wave of running men. “Come on, get going,” they shouted; “the Jerries have broken through, and it’s every man for himself.” They swarmed over the truck, piling on the roof, the hood, the fenders.

Shattock headed west, flowing with the tide. At first he made good mileage, but gradually the drive became a nightmare. Stuka dive bombers poured out of a dazzling sun. They had let the British columns advance deep into Belgium without interference, but the trip back was different. With toy whistles attached to both planes and bombs (the Germans called them the “trumpets of Jericho”), they screeched down in an orgy of killing and terror. Pulling out of their dives, they flew along the roads at car-top height, strafing for good measure.

The hot, still air filled with black smoke and the smell of burning rubber; the traffic slowed to a crawl. Weeping refugees swarmed among the dazed troops. Discarded hand-carts, bicycles, baby carriages, burnt-out family cars lay cluttered along the roadside.

Finally the traffic stopped altogether. Shattock’s passengers, seeing they could make better time on foot, abandoned him, and soon he sat alone in his stalled truck. He climbed onto the roof, but could see no way out. Traffic had piled up behind as well as ahead, and deep ditches on either side of the road ruled out any cross-country escape. He was simply glued in place on this blazing hot, smoky May afternoon. He had never felt so alone and helpless. Before, there had always been someone to give orders. Here, there was no one.

Actually, he could not have been very far from his own regiment, which had disappeared so mysteriously the previous day. They had pulled out when a battery observer, sent up a telegraph pole, reported “a lot of soldiers with coal scuttles on their heads a couple of fields away.”

To Lance Bombardier H. E. Gentry, it was the chariot race in Ben-Hur all over again. The regiment hooked up their guns … roared out of the meadow … and swung wildly onto the main road, heading back the way they had come.

It was dark by the time they stopped briefly to fire off all their ammunition—at extreme range and at no particular target, it seemed. Then on again into the night. Gentry hadn’t the remotest idea where they were going; it was just a case of follow the leader.

Midnight, they stopped again. It was raining now, and the exhausted men huddled around a low-burning fire, munching stew and trading stories of the hell they had been through.

Dawn, the rain stopped, and they were off again into another beautiful day. A German Fieseler Storch observation plane appeared, flying low, hovering over them, clearly unafraid of any interference. The men of the 32nd understood: they hadn’t seen a sign of the RAF since the campaign began. From past experience, they also knew that rifles were useless. In exasperation Gentry blazed away anyhow, but he knew that the real time to worry was when the Storch left.

When it finally did veer off, a dozen bombers appeared from the right. The 32nd came to a jolting stop at the edge of a village, and the shout went up, “Disperse—take cover!” Gentry ran into a farmyard, deep in mud and slime; he dived into a hayrick as the planes began unloading. Bedlam, capped by one particularly awesome swoosh, and the ground shook like jelly. Then the silence of a cemetery.

Gentry crept out. There, stuck in the slime a few feet away, was a huge unexploded bomb. It was about the size of a household refrigerator, shaped like a cigar, with its tail fins sticking up. A large pig slowly waddled across the barnyard and began licking it.

On again. To Gentry, the 32nd seemed to be going around in circles. They always seemed to be lost, with no set idea where they were supposed to be or where they were going. Occasionally they would stop, fire off a few rounds (he never knew the target), and then, on their way again. His mind drifted back to last winter in Lille, where he and his friends would go to their favorite café and sing “Run Rabbit Run.” Now, he ruefully thought, We are the rabbits and are we running!

At the River Dendre the 32nd once again got ready to go into action. Traffic was particularly bad here—few crossings and everyone trying to get over. Gentry noticed a number of motorcycles with sidecars moving into a field on the left. The soldiers in the sidecars jumped out and began spraying the 32nd with machine guns.

Jerry had arrived. The British gunners scrambled into action, firing over open sights, and for five minutes it was a rousing brawl. Finally they drove the motorcyclists off, but there was no time to celebrate: a squadron of German fighters swooped down from out of the sun and began strafing the road.

As if this wasn’t enough, word spread of a new peril. Enemy troops masquerading as refugees were said to be infiltrating the lines. From now on, the orders ran, all women were to be challenged by rifle. What next? wondered Lance Bombardier Gentry; Germans in drag!

Fear of Fifth Columnists spread like an epidemic. Everyone had his favorite story of German paratroopers dressed as priests and nuns. The men of one Royal Signals maintenance unit told how two “monks” visited their quarters just before a heavy bombing attack. Others warned of enemy agents, disguised as Military Police, deliberately misdirecting convoys. There were countless tales of talented “farmers” who cut signs in corn and wheat fields pointing to choice targets. Usually the device was an arrow; sometimes a heart; and in one instance the III Corps fig leaf emblem.

The Signals unit attached to II Corps headquarters had been warned that the Germans were dropping spies dressed as nuns, clergy, and students, so they were especially on their guard as they pulled off the main road for a little rest one dark night during the retreat. Dawn was just breaking when they were awakened by the sentry’s shouts. He reported a figure trailing a parachute lurking among some trees. After two challenges got no response, the section sergeant ordered the sentry and Signalman E. A. Salisbury to open fire. The figure crumpled, and the two men ran up to see what they had hit. It turned out to be a civilian in a gray velvet suit, clutching not a parachute but an ordinary white blanket. He had died instantly and carried no identification.

The sergeant muttered something about one less Boche in the world, and the unit was soon on the road again. It was only later that Salisbury learned the truth: an insane asylum at Louvain had just released all its inmates, and one of them was the man he had shot. The incident left Salisbury heartsick, and forty years later he still worried about it.

There were, of course, cases of real Fifth Column activity. Both the 1st Coldstream and the 2nd Gloucesters, for instance, were harassed by sniper fire. But for the most part the “nuns” were really nuns, and the priests were genuine clerics whose odd behavior could be explained by pure fright. Usually the Military Police who misdirected traffic were equally genuine—just a little mixed up in their work.

Yet who could know this at the time? Everyone was suspicious of everyone else, and Bombardier Arthur May found that life could be deadly dangerous for a straggler. He and two mates had been separated from their howitzer battery. They heard it had pulled back to the Belgian town of Tournai on the Escaut, and now they were trying to catch up with it. As they drove the company truck along various back roads, they were stopped and interrogated again and again by the British rear guard, all of whom seemed to have itchy trigger-fingers.

Finally they did reach Tournai, but their troubles weren’t over. A sergeant and two privates, bayonets fixed, made them destroy their truck. Then they were escorted across the last remaining bridge over the Escaut, put in the charge of three more tough-talking riflemen, and marched to a farmhouse on the edge of town. Here they were split up and put through still another interrogation.

Cleared at last, the three men searched two more hours before they finally found their battery. Nobody wanted to tell them anything, and the few directions they pried loose were intentionally misleading. May found it hard to believe that all these unfriendly chaps were his own comrades-in-arms.

But it was so; and more than that, these grim, suspicious rear-guard units were all that stood between the confused mass of retreating troops and the advancing Germans. Some, like the Coldstream and the Grenadiers, were Guards regiments of legendary discipline. Others, like the 5th Northamptons and the 2nd Hampshires, were less famous but no less professional. The standard routine was to dig in behind some canal or river, usually overnight, hold off the German advance during the day with artillery and machine guns, then pull back to the next canal or river and repeat the formula.

They were as efficient as machines, but no machines could be so tired. Digging, fighting, falling back; day after day there was never time to sleep. The 1st East Surreys finally invented a way to doze a little on the march. By linking arms, two outside men could walk a man between them as he slept. From time to time they’d switch places with one another.

When Lieutenant James M. Langley of the 2nd Coldstream was put in charge of the bridge across the Escaut at Pecq, the Company commander, Major Angus McCorquodale, ordered a sergeant to stand by and shoot Langley if he ever tried to sit or lie down. Langley’s job was to blow the bridge when the Germans arrived, and McCorquodale explained to him, “The moment you sit or lie down, you will go to sleep, and that you are not going to do.”

The enemy advance was often no more than ten or fifteen minutes away, but by May 23 most of the troops somehow got back to the French frontier, the starting point of their optimistic plunge into Belgium only two weeks earlier. The first emotion was relief, but close behind came shame. They all remembered the cheers, the flowers, the wine that had greeted them; now they dreaded the reproachful stares as they scrambled back through the rubble of each burned-out town.

With the 1st East Surrey’s return to France, 2nd Lieutenant R. C. Taylor was ordered to go to Lille to pick up some stores. Lille lay far to the rear of the battalion’s position, and Taylor expected to find the assignment a peaceful change from the hell he had been through in Belgium. To his amazement, the farther back he drove, the heavier grew the sound of battle. It finally dawned on him that the Germans lay not only to the east of the BEF, but to the south and west as well. They were practically surrounded.

The scratch forces that General Gort had thrown together to cover his exposed flank and rear were desperately hanging on. South of Arras, the inexperienced 23rd Division faced General Major Erwin Rommel’s tanks without a single antitank gun. At Saint Pol a mobile bath unit struggled to hold off the 6th Panzer Division. At Steenbecque the 9th Royal Northumberland Fusiliers grimly bided their time. A scantily trained Territorial battalion, they had been building an airfield near Lille when “the balloon went up.” Now they were part of an improvised defense unit called POLFORCE. They had no instructions, only knew that their commanding officer had vanished.

At this point Captain Tufton Beamish, the only regular army officer in the battalion, assumed command. Somehow he rallied the men, dug them into good positions, placed his guns well, and managed to hold off the Germans for 48 important hours.

Things were usually not that tidy. Private Bill Stratton, serving in a troop-carrying unit, felt he was aimlessly driving all over northeastern France. One evening the lorries were parked in a tree-lined field just outside the town of Saint-Omer. Suddenly some excited Frenchmen came pouring down the road shouting “Les Boches! Les Boches!” A hastily dispatched patrol returned with the disquieting news that German tanks were approaching, about ten minutes away.

The men stood to, armed only with a few Boyes antitank rifles. This weapon did little against tanks but had such a kick it was said to have dislocated the shoulder of the inventor. Orders were not to fire until the word was given.

Anxious moments, then the unmistakable rumble of engines and treads. Louder and louder, until—unbelievably—there they were, a column of tanks and motorized infantry clanking along the road right by the field where Stratton crouched. The trees apparently screened the lorries, for the tanks took no notice of them, and the British never attracted attention by opening fire. Finally they were gone; the rumbling died away; and the troop-carrier commander began studying his map, searching for some route back that might avoid another such heart-stopping experience.

It was so easy to be cut off, lost—or forgotten. Sapper Joe Coles belonged to an engineering company that normally serviced concrete mixers but was now stuffed into MACFORCE east of Arras. They had no rations or water and were trying to milk some cows when Coles was posted off with a sergeant to repair a pumping station near the town of Orchies.

By the following evening the two men had the pumps going again and decided to go into Orchies, since they still had no rations, nor even a blanket. The place turned out to be a ghost town—citizens, defending garrison, everybody had vanished.

They did find a supply depot of the Navy, Army and Air Force Institute. British servicemen always regarded NAAFI as the ministering angel for all their needs, but even in his wildest dreams Coles never imagined anything like this. Here, too, all the staff was gone, but the shelves were packed with every conceivable delicacy.

A stretcher was found and loaded with cigarettes, whisky, gin, and two deck chairs. Back at the pumping station, Coles and the sergeant mixed themselves a couple of generous drinks and settled down in the deck chairs for their best sleep in days.

Next morning, still no orders; still no traffic on the roads. It was now clear that they had been left behind and forgotten. Later in the day they spotted four French soldiers wandering around the farm next door. The poilus had lost their unit too, and on the strength of this bond, Coles dipped into his NAAFI hoard and gave them a 50-pack of cigarettes. Overwhelmed, they reciprocated with a small cooked chicken. For Coles and the sergeant it was their first meal in days, and although they didn’t know it yet, it would also be their last in France.

At the moment they thought only about getting away from the pumping station. The disappearance of everybody could only mean they were in no-man’s-land. By agreement, Coles went down to the main road and began waiting on the off-chance that some rear-guard vehicle might happen by. It was a long shot, but it paid off when a lone British Tommy on a motorcycle came boiling along. Coles flagged him down, and the Tommy promised to get help from a nearby engineering unit, also lost and forgotten. Within twenty minutes a truck swerved into the pumping station yard, scooped up Coles and his companion, and sped north toward relative safety and the hope, at least, of better communications.

The communications breakdown was worst in the west—an inevitable result of slapping together those makeshift defense units—but the problem was acute everywhere. From the start of the war the French high command had rejected wireless. Anybody could pick signals out of the air, the argument ran. The telephone was secure. This meant stringing miles and miles of cable, and often depending on overloaded civilian circuits—but at least the Boches wouldn’t be listening.

Lord Gort cheerfully went along. Once again, the French were the masters of war; they had studied it all out, and if they said the telephone was best, the BEF would comply. Besides, the French had 90 divisions; he had only ten.

Then May, and the test of battle itself. Some telephone lines were quickly chewed up by Rundstedt’s tanks. Others were inadvertently cut by Allied units moving here and there. Other breaks occurred as various headquarters moved about. Gort’s Command Post alone shifted seven times in ten days. The exhausted signalmen couldn’t possibly string lines fast enough.

After May 17 Gort no longer had any direct link with Belgian headquarters on his left, with French First Army on his right, or with his immediate superior General Georges to the rear. Nor were orders getting through to most of his own commanders down the line. At Arras his acting Operations Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel the Viscount Bridgeman, soon decided it was hopeless to rely on GHQ. Living on a diet of chocolate and whisky, he simply did what he thought was best.

The only reliable way to communicate was by personal visit or by using dispatch riders on motorcycle. Driving through the countryside, the jaunty commander of 3rd Division, Major-General Bernard Montgomery, would jam a message on the end of his walking stick and hold it out the car window. Here it would be plucked off by his bodyguard, Sergeant Arthur Elkin, riding up on a motorcycle.

Elkin would then scoot off to find the addressee. But it was a tricky business, driving along strange roads looking for units constantly on the move. Once he rode up to three soldiers sitting on a curb, hoping to get some directions. As he approached, one of the soldiers put on his helmet, and Elkin realized just in time that they were German.

To Gort, the communications breakdown was one more item in a growing catalogue of complaints against the French. Gamelin was a forlorn cipher. General Georges seemed in a daze. General Gaston Billotte, commanding the French First Army Group, was meant to coordinate but didn’t. Gort had received no written instructions from him since the campaign began.

The French troops along the coast and to the south seemed totally demoralized. Their horse-drawn artillery and transport cluttered the roads, causing huge traffic jams and angry exchanges. More than one confrontation was settled at pistol-point. Perhaps because he had gone along with the French so loyally for so long, Gort was now doubly disillusioned.

It’s hard to say when the idea of evacuation dawned on him, but the moment may well have come around midnight, May 18. This was when General Billotte finally paid his first visit to Gort’s Command Post, currently in Wahagnies, a small French town south of Lille. Normally a big, bluff, hearty man, Billotte seemed weary and deflated as he unfolded a map showing the latest French estimate of the situation. Nine panzer divisions had been identified sweeping west toward Amiens and Abbeville—with no French units blocking their way.

Billotte talked about taking countermeasures, but it was easy to see that his heart was not in it, and he left his hosts convinced that French resistance was collapsing. Since the enemy now blocked any retreat to the west or south, it appeared that the only alternative was to head north for the English Channel.

At 6:00 a.m., May 19, six of Gort’s senior officers met to begin planning the retreat. It turned out that the Deputy Chief of Staff, Brigadier Sir Oliver Leese, had already been doing some thinking; he had roughed out a scheme for the entire BEF to form a hollow square and move en masse to Dunkirk, the nearest French port.

But this assumed that the army was already surrounded, and it hadn’t come to that. What was needed was a general pulling back, and as a first step GHQ at Arras closed down, with part of the staff going to Boulogne on the coast and the rest to Hazebrouck, 33 miles closer to the sea. For the moment the Command Post would remain at Wahagnies.

At 11:30 the Chief of Staff, Lieutenant-General H. R. Pownall, telephoned the War Office in London and broke the news to the Director of Military Operations and Plans, Major-General R. H. Dewing. If the French could not stabilize the front south of the BEF, Pownall warned, Gort had decided to pull back toward Dunkirk.

In London it was a serenely beautiful Sunday, and the elegant Secretary of State for War, Anthony Eden, was about to join Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax for a quiet lunch, when he received an urgent call to see General Sir Edmund Ironside, Chief of the Imperial General Staff. Ironside, a hulking, heavy-footed man (inevitably nicknamed “Tiny”), was appalled by Gort’s proposed move to Dunkirk. It would be a trap, he declared.

Ironside’s consternation was evident when at 1:15 p.m. a new call came in from Pownall. Dewing, again on the London end of the line, suggested that Gort was too gloomy, that the French might not be as badly off as he feared. In any case, why not head for Boulogne or Calais, where air cover would be better, instead of Dunkirk? “It’s a case of the hare and the tortoise,” Pownall answered dryly, “and a very simple calculation will show that the hare would win the race.”

Dewing now put forward Ironside’s pet solution: the BEF should turn around and fight its way south to the Somme. It was a theory that totally overlooked the fact that most of the British Army was locked in combat with the German forces to the east and couldn’t possibly disengage, but Pownall didn’t belabor the point. Instead he soothingly reassured Dewing—again and again—that the Dunkirk move was “merely a project in the mind of the C-in-C” … that it was just an idea mentioned only to keep London informed of Headquarters’ thinking … that any decision depended on whether the French could restore their front. Since he was already on record as saying that the French were “melting away,” London was understandably not mollified.

Dewing took another tack: Did Pownall realize that evacuation through Dunkirk was impossible and that maintaining any force there was bound to be precarious? Yes, Pownall answered, he knew that, but heading south would be fatal. The conversation ended with Pownall feeling that Dewing was “singularly stupid and unhelpful,” and with the War Office convinced that Gort was about to bottle himself up.

Ironside urged that the War Cabinet be convened at once. Messages went out recalling Churchill and Chamberlain, who had each gone off for a quiet Sunday in the country, and at 4:30 p.m. the Cabinet assembled in what Churchill liked to call “the fish room” of the Admiralty—a chamber festooned with carved dolphins leaping playfully around.

Churchill agreed with Ironside completely: the only hope was to drive south and rejoin the French on the Somme. The others present fell in line. They decided that Ironside should personally go to Gort—this very night—and hand him the War Cabinet’s instructions.

At 9:00 p.m. Ironside caught a special train at Victoria Station. … At 2:00 a.m. on the 20th he was in Boulogne … and at 6:00 he came barging into Gort’s Command Post at Wahagnies. With the War Cabinet’s order backing him up, he told Gort that his only chance was to turn the army around and head south for Amiens. If Gort agreed, he’d issue the necessary orders at once.

But Gort didn’t agree. For some moments, he silently pondered the matter, then explained that the BEF was too tightly locked in combat with the Germans to the east. It simply couldn’t turn around and go the other way. If he tried, the enemy would immediately pounce on his rear and tear him to bits.

Then, asked Ironside, would Gort at least spare his two reserve divisions for a push south which might link up with a French force pushing north? Gort thought this might be possible, but first they must coordinate the effort with General Billotte, the overall commander for the area.

Taking Pownall in tow, Ironside now rushed down to French headquarters at Lens. He found Billotte with General Blanchard of the French First Army—both in a state of near collapse. Trembling and shouting at each other, neither had any plans at all. It was too much for the volcanic Ironside. Seizing Billotte by the buttons on his tunic, he literally tried to shake some spirit into the man.

Ultimately it was agreed that some French light mechanized units would join Gort’s two reserve divisions in an attack tomorrow south of Arras. They would then meet up with other French forces pushing north. A command change at the very highest level should help: the placid Gamelin had finally been replaced by General Maxime Weygand. He was 73, but said to be full of fire and spirit.

Ironside now returned to London, convinced that once the two forces joined, the way would finally be opened for the BEF to turn around and head south—still his pet solution for everything. Gort remained unconvinced, but he was a good soldier and would try.

At 2:00 p.m., May 21, a scratch force under Major-General H. E. Franklyn began moving south from Arras. If all went well, he should meet the French troops heading north in a couple of days at Cambrai. But all didn’t go well. Most of the infantry that Franklyn had on paper were tied up elsewhere. Instead of two divisions he had only two battalions. His 76 tanks were worn out and began to break down. The French support on his left was a day late. The new French armies supposedly moving up from the Somme never materialized. The Germans were tougher than expected. By the end of the day Franklyn’s attack had petered out.

This was no surprise to General Gort. He had never had any faith in a drive south. Midafternoon, even before Franklyn ran into trouble, Gort was giving his corps commanders a gloomy picture of the overall situation. Franklyn’s attack was brushed off as “a desperate remedy in an attempt to put heart in the French.”

Meanwhile, at another meeting of staff officers, Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Brownrigg, Gort’s Adjutant-General, ordered rear GHQ to move from Boulogne to Dunkirk; medical personnel, transport troops, construction battalions, and other “useless mouths” were to head there at once. Later, at still another meeting, a set of neat, precise instructions was issued for the evacuation of these troops: “As vehicles arrive at various evacuation ports, drivers and lorries must be kept, and local transport staffs will have to make arrangements for parking. …”

But neither Gort nor anyone from his staff attended the most important conference held this hectic afternoon. The new Supreme Commander General Weygand had flown up from Paris and was now at Ypres, explaining his plan to the commanders of the trapped armies, including Leopold III, King of the Belgians. But Gort couldn’t be located. He had once again shifted his Command Post—this time to Prémesques, just west of Lille—and by the time he and Pownall arrived at Ypres, it was too late. Weygand had gone home.

This meant that Gort had to learn about Weygand’s plan secondhand from Billotte, which was unfortunate, since the British were to play a crucial role. The BEF was to spearhead still another drive south, linking up with a new French army group driving north. If the French and Belgians could take over part of his line, Gort agreed to contribute three divisions—but not before May 26.

He agreed, but that didn’t make him a true believer. Once back in Prémesques, Pownall immediately summoned the acting Operations Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Bridgeman. The purpose, it turned out, was not to get Bridgeman working on the drive south. Rather, he was to draw up a plan for retiring north … for withdrawing the whole BEF to the coast for evacuation.

Bridgeman worked on it all night. Starting with the premise that an evacuation could take place anywhere between Calais and Ostend, he had to find the stretch of coast that could most easily be reached and defended by the three corps that made up the BEF. Which had the best roads leading to it? Which had the best port facilities? Which offered the best chance for air cover? Which had the best terrain for defense? Were there canals that could be used to protect the flanks? Towns that could serve as strong-points? Dykes that could be opened to flood the land and stop those German tanks?

Poring over his maps, he gradually decided that the best bet was the 27-mile stretch of coast between Dunkirk and the Belgian town of Ostend. By the morning of May 22 he had covered every detail he could think of. Each corps was allocated the routes it would use, the stretch of coast it would hold.

This same morning Winston Churchill again flew to Paris, hoping to get a clearer picture of the military situation. Reynaud met him at the airport and whisked him to Grand Quartier Général at Vincennes, where the oriental rugs and Moroccan sentries lent an air of unreality that reminded Churchill’s military adviser, General Sir Hastings Ismay, of a scene from Beau Geste.

Here the Prime Minister met for the first time Maxime Weygand. Like everyone else, Churchill was impressed by the new commander’s energy and bounce (like an India rubber ball, Ismay decided). Best of all, his military thinking seemed to parallel Churchill’s own. As he understood it, the Weygand Plan in its latest refinement called for eight divisions from the BEF and the French First Army, with the Belgian cavalry on the right, to strike southwest the very next day. This force would “join hands” with the new French army group driving north from Amiens. That evening Churchill wired Gort his enthusiastic approval.

“The man’s mad,” was Pownall’s reaction when the wire reached Gort’s Command Post next morning, the 23rd. The military situation was worse than ever: in the west, Rundstedt’s Army Group A was closing in on Boulogne, Calais, and Arras; to the east, Bock’s Army Group B was pushing the lines back to the French frontier. Churchill, Ironside—all of them—clearly had no conception of the actual situation. Eight divisions couldn’t possibly disengage … the French First Army was a shambles … the Belgian cavalry was nonexistent—or seemed so.

Worse, Billotte had just been killed in a traffic accident, and he was the only man with firsthand knowledge of Weygand’s plans. His successor, General Blanchard, seemed a hopeless pedant, lacking any drive or power of command. With all coordination gone, troops from three different countries couldn’t conceivably be thrown into battle on a few hours’ notice.

London and Paris dreamed on. After the meeting with Churchill, Weygand issued a stirring “Operation Order No. 1.” In it he called on the northern armies to keep the Germans from reaching the sea—ignoring the fact that they were already there. On May 24 he announced that a newly formed French Seventh Army was advancing north and had already retaken Péronne, Albert, and Amiens. It was all imaginary.

Churchill too lived in a world of fantasy. On the 24th he fired a barrage of questions at General Ismay. Why couldn’t the British troops isolated at Calais simply knife through the German lines and join Gort? Or why didn’t Gort join them? Why were British tanks no match for German guns, but British guns no match for German tanks? The Prime Minister remained sold on the Weygand Plan, and a wire from Eden urged Gort to cooperate.

The General was doing his best. The attack south—his part of the Weygand Plan—was still on, although the BEF contribution had been cut from three to two divisions. The German pressure in the east left no other course. As an extra precaution, Colonel Bridgeman had also been told to bring his evacuation plan up to date, and the Colonel produced a “second edition” on the morning of the 24th. Finally, Gort asked London to send over the Vice-Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Lieutenant-General Sir John Dill. Until April, Dill had been Gort’s I Corps Commander. He was more likely to understand. If he could see for himself how bad things were, he might take back a little sanity to London.

“There is no blinking the seriousness of situation in Northern Area,” Dill reported an hour and ten minutes after his arrival on the morning of May 25. His wire went on to describe the latest German advances. He assured London that the Allied drive south was still on, but added, “In above circumstances, attack referred to above cannot be important affair.”

At this point General Blanchard appeared. In a rare moment of optimism he said the French could contribute two or three divisions and 200 tanks to the drive. Dill returned to London in a hopeful mood—he had more faith than Gort in French figures.

This was the last good news of the day. Starting around 7:00 a.m., reports began coming in from the east that the Belgian line was cracking just where it joined the British near Courtrai. If this happened, Bock’s Army Group B would soon link up with Rundstedt’s Army Group A to the west, and the BEF would be completely cut off from the sea.

There were no Belgian reserves. If anyone were to stop the Germans, it would have to be the British. Yet they too were spread dangerously thin. When Lieutenant-General Alan Brooke, commanding the endangered sector, appealed to headquarters, the most that Gort could spare was a brigade.

Not enough. The news grew worse. The usually reliable 12th Lancers reported that the enemy had punched through the Belgian line on the River Lys. A liaison officer from the 4th Division said that the Belgians on his front had stopped fighting completely; they were just sitting around in cafés.

By 5:00 p.m. Gort had heard enough. He retired alone to his office in Prémesques to ponder the most important decision of his professional career. All he had left were the two divisions he had promised for the attack south tomorrow. If he sent them north to plug the gap in the Belgian line, he would be ignoring his orders; he would be reneging on his understanding with Blanchard; he would be junking not only the Weygand Plan but the thinking of Churchill, Ironside, and all the rest; he would be committing the BEF to a course that could only lead to the coast and a risky evacuation.

On the other hand, if he sent these two divisions south as promised, he would be cut off from the coast and completely encircled. His only chance then would be a last-minute rescue by the French south of the Somme, and he had no faith in that.

His decision: send the troops north. At 6:00 p.m. he canceled the attack south and issued new orders: one of the divisions would join Brooke immediately; the other would follow shortly. Considering Gort’s utter lack of faith in the French, it was a decision that should have required perhaps less than the hour it took. The explanation lay in Gort’s character. Obedience, duty, loyalty to the team were the mainsprings of his life. To go off on his own this way was an awesome venture.

If anything were needed to steel his resolve, it came in the form of a leather wallet stuffed with papers and a small bootjack, which had been found in a German staff car shot up by a British patrol. Brooke brought the wallet with him when he arrived at the Command Post for a conference shortly after Gort made his big decision. While he and Gort conferred, the intelligence staff examined the documents in the wallet. These included plans for a major attack at Ypres—confirming the wisdom of Gort’s decision to call off the drive south and shift the troops north.

There was only one worry. Could the papers be a “plant”? No, Brooke decided, the bootjack meant they were genuine. Not even Hitler’s brightest intelligence agents would have thought of that touch. Far more likely, the wallet belonged to some real staff officer whose boots were too tight.

Gort’s decision might not have been so difficult had he known that London was also going through some soul searching. Dill had returned, and his assessment finally convinced the War Office that Gort’s plight was truly desperate. Reports from liaison officers indicated that the French along the Somme couldn’t possibly help; the new armies were just beginning to assemble. Later that evening the three service ministers and their chiefs of staff met, and at 4:10 a.m., May 26, War Secretary Eden telegraphed Gort that he now faced a situation in which the safety of the BEF must come first.

In such conditions only course open to you may be to fight your way back to west where all beaches and ports east of Gravelines will be used for embarkation. Navy would provide fleet of ships and small boats and RAF would give full support. … Prime Minister is seeing M. Reynaud tomorrow afternoon when whole situation will be clarified, including attitude of French to the possible move. In meantime it is obvious that you should not discuss the possibility of the move with French or Belgians.

Gort didn’t need to be told. When he received Eden’s telegram he had just returned from a morning meeting with General Blanchard. There he reviewed his decision to cancel the attack south; he won French approval for a joint withdrawal north; he worked out with Blanchard the lines of retreat, a timetable, a new defense line along the River Lys—but never said a word about evacuation. In fact, as Blanchard saw things, there would be no further retreat. The Lys would be a new defense line covering Dunkirk, giving the Allies a permanent foothold in Flanders.

For Gort, Dunkirk was no foothold; it was a springboard for getting the BEF home. His views were confirmed by a new wire from Eden that arrived late in the afternoon. It declared that there was “no course open to you but to fall back upon the coast. … You are now authorized to operate towards the coast forthwith in conjunction with French and Belgian armies.”

So evacuation it was to be, but now a new question arose: Could they evacuate? By May 26 the BEF and the French First Army were squeezed into a long, narrow corridor running inland from the sea—60 miles deep and only 15 to 25 miles wide. Most of the British were concentrated around Lille, 43 miles from Dunkirk; the French were still farther south.

On the eastern side of the corridor the trapped Allied forces faced Bock’s massive Army Group B; on the western side they faced the tanks and motorized divisions of Rundstedt’s Army Group A. His panzers had reached Bourbourg, only ten miles west of Dunkirk. It seemed almost a mathematical certainty that the Germans would get there first.

“Nothing but a miracle can save the BEF now,” General Brooke noted in his diary as the pocket took shape on May 23.

“We shall have lost practically all our trained soldiers by the next few days—unless a miracle appears to help us,” General Ironside wrote on the 25th.

“I must not conceal from you,” Gort wired Anthony Eden on the 26th, “that a great part of the BEF and its equipment will inevitably be lost even in the best circumstances.”

Winston Churchill thought that only 20,000 or 30,000 men might be rescued. But the Prime Minister also had a streak of pugnacious optimism. In happier days he and Eden had once met at Cannes and won at roulette by playing No. 17. Now, as the War Cabinet met on one particularly grim occasion, he suddenly turned to Eden and observed, “About time No. 17 turned up, isn’t it?”

* This book uses the geographical names that were most common at the time. Today the River Escaut is generally known as the Scheldt; the town of La Panne has become De Panne.