In this classic game-theory puzzle, the best thing you can do is to squeal like a pig. Imagine your sentences in the following possible scenarios:

• You remain silent, your partner squeals: ten years.

• You remain silent, your partner remains silent: six months.

• You squeal, your partner squeals: five years.

• You squeal, your partner stays silent: you walk.

So look, no matter if your partner squeals or if he stays quiet, your sentence is reduced if you squeal. Unfortunately, your partner’s working with the same information. He’s gonna squeal too, and you’ll both end up with five years, when you both could have gotten six months if you’d both stayed quiet.

The prisoner’s dilemma is an example of Nash equilibrium in which individuals act in their best interests and bring the situation to an equilibrium—but not necessarily the optimal one! If they’d cooperated instead of acting selfishly, they could have punched through Nash equilibrium into optimization.

The prisoner’s dilemma has implications for social policy. Should every individual be left to fend for him- or herself (as in Ayn Rand’s social Darwinism, where the fittest individuals prosper)? Or is the group bettered by mutual aid programs? Should society be left to find its own Nash equilibrium, or should government provide incentives for desired behaviors?

2,2,2 beats 1,1,4 and ties against all other strategies (1,2,3 and 2,2,2), so it “weakly dominates” all other choices and is Colonel Blotto’s best strategy.

2,4,6 ties 1,4,7 and 2,4,6 and 3,4,5 and 4,4,4, and beats the rest. Thus it “weakly dominates” all other choices and is Colonel Blotto’s best strategy.

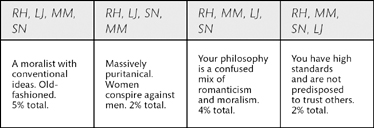

Find your answers in the following chart. RH = Robin Hood, LJ = Little John, MM = Maid Marian, SN = Sheriff of Nottingham. Percentages show people’s common responses. Note: Figures are rounded to the nearest percentage.

This short test measures your trust. First add the scores for questions 1, 3, 4, and 7. Then subtract your scores for questions 2, 5, 6, and 8. The best way to interpret your score would be in comparison with those of other test-takers, but very generally, a positive score indicates that you’re trustful while a negative score indicates you’re distrustful.

At the end of each day, the prisoner can look forward and say I must be executed on a later day, allowing him to deduce the day of his execution and thus avoid execution (’cause he can’t know the day ahead of time; if he does, he can’t be executed). But this assumes he can make it to the end of the day. In other words, he can’t ever rule out being executed in the present day. If days were inviolable chunks, he would survive, but they’re not—he can be executed without warning at any time.

It makes sense to put the torch in A’s quick hands and let him/her run with it, shuttling people across and returning with the torch. But that takes 18 minutes: A takes B and then returns the torch: 3 minutes. A takes C and then returns alone: 6 minutes. A takes D: 9 minutes.

Better to stick the slowest people together, but with someone else to return the torch: A takes B and then returns the torch: 3 minutes. C and D cross together and then B returns the torch: 10 minutes. A and B sprint across together: 2 minutes, for a total of 15 minutes.

Your best strategy is to leave very early and drive very fast—if you mashed the pedal at 5:30, you could perhaps make it home by 6:15. Even assuming you can’t make the whole trip before your mom starts driving, you should still leave-early/drive-fast—the faster you drive, the less time it’ll take to meet your mother on the way out, and your drive home will simply double this shortened time.

On the scale, place one bar from box number one, two bars from box two, three bars from box three, etc. Now the number of 20ths below the expected weight tells you which box is counterfeit.

If you bet, your opponent folds with a Jack or raises with a King. Half the time, you win your opponent’s one-chip ante, and half the time you lose your ante plus your bet.

This is not good. In fact, it’s bad. You’re losing twice as many chips as you’re winning.

So you check.

Now your opponent checks only if holding the Jack and you win. If your opponent bets he/she either has the King or is bluffing with the Jack. So calling this bet wins half the time (assuming your opponent is an ice-cold bluffer). If you call, you’ve got two chips versus two chips in a 50/50 pot; if you fold, you lose your ante every time.

So your best strategy when holding the Queen and playing first is to check and then call if necessary.

Serious game-theory geeks should search online for Steve Kuhn’s description of three-card poker, in which he shows that with both players playing optimally, the first player loses 1/18th of his stack over time.

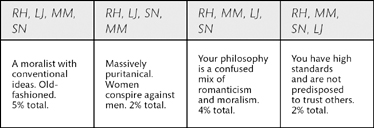

This self-test is one of the shortest scientifically accurate assessments of the “Big Five” personality factors: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and intellect/imagination. While it’s best to interpret these scores relative to other people taking the test, you can get an overview of your personality by looking for especially high and low scores, and noticing which of the five personality traits seem to outweigh others.

Here’s how to score the test: First, write your score (1 through 5) for each question next to that question’s + or – mark. Now you’ll need to go through your answers one trait at a time; for instance, note that questions 1, 6, 11, and 16 are all marked “E.” That means they all measure extraversion, and we’ll need to combine our answers to them to get our extraversion score. Answers with a + mark in front of them should be added to your total score for a trait; those with a – mark should be subtracted. So, looking at extraversion again, you’d add your score for question 1, subtract your score for question 6, add your score for question 11, and subtract your score for question 16 to get your total extraversion score. Do the same with the remaining four traits. Which of the five do you score highest on? Lowest?

Did you say 50/50 both times? Wrong! Imagine the four possibilities for a two-child family: girl-girl, girl-boy, boy-girl, and boy-boy. In the first case, we know the first child’s a girl, so we can cross off the last two options (boy-girl and boy-boy), leaving the options girl-girl and girl-boy. OK, in this case you’re right: there is a 50 percent chance the second child’s a girl.

Now let’s look at the second case.

If we know that “at least one of them is a boy,” we can cross off only girl-girl, leaving girl-boy, boy-boy, and boy-girl. Notice that only one of the remaining three scenarios is boy-boy. As counterintuitive as it may seem, after specifying that “one child is a boy,” there’s only a one-in-three or 33 percent chance that both are.

Well, the maximum possible average of numbers from 0 to 100 is 100 and so you’re certainly not going to guess above 66.67 (which is % of 100). You can be assured that the other game theory experts in your guessing group aren’t going to guess above 66.67 either. So you can consider 66.67 the maximum possible guess. Now the maximum you’d want to guess is two-thirds of that, or 44.45. And that’s true for everyone. So now you can be assured that no one will guess over 44.45. Eventually, you can extend this reasoning all the way to 0, which is your best guess.

In practice, the winning guess in a Dutch version of this game, which drew almost 20,000 entries, was 21.6. Apparently, not every Netherlander is versed in game theory.

This short test measures your happiness. First add the scores for questions 2, 3, 6, 8, and 10. Then subtract your scores for questions 1, 4, 5, 7, and 9. The best way to interpret your score would be in comparison with those of other test-takers, but very generally, a positive score indicates that you’re more happy than sad.

Look at the puzzle pieces. Included are two right triangles, one 5 × 2 and another 8 × 3. Here’s the thing: Their hypotenuses (top sides, here) sit at slightly different angles. And so when we stack these triangles tip-to-top as in this puzzle, it creates a very slight bend in the hypotenuse of the resulting, larger “triangle.” We’re used to seeing right triangles, so we don’t notice it. So the hypotenuse of the top figure caves slightly inward, while the hypotenuse of the lower figure bends slightly up, allowing the bottom figure a little more area than the top. Thus the extra box.

The catch-22 is that any “best” strategy is doomed to fail: If everyone decides to stay home, the bar will be empty and thus fun; if everyone decides to go, the bar will be crowded and people should’ve stayed home.

And so the best strategy is a mixed strategy in which each person has a set probability of going. The probability depends on how many people are deciding, the capacity of the bar, and how close the experience of staying home is to the experience of going to the bar.

If you can communicate and lie, you should say that you’re going to the bar, every time. If you end up going, your truth may have scared others away; if you stay home, your lie hasn’t hurt you at all.

The man in the foreground’s fishing rod’s line passes behind that of the man behind him.

The sign is moored to two buildings, one in front of the other, with beams that show no difference in depth

The sign is overlapped by two distant trees.

The man climbing the hill is lighting his pipe with the candle of the woman leaning out of the upper story window.

The crow perched on the tree is massive in comparison with it.

Believe it or not, the pirate king need only split the 100 gold pieces as follows: 98 for himself, none for B, one for C, none for D, and one for E.

Imagine it came down to pirates D and E. D could keep all the gold, with the one-to-one tied vote falling in his favor. E knows this.

And so does C. So C only needs to offer E one gold piece to ensure E’s vote (that’s one more than E would get otherwise).

But B knows this too. So B offers D one gold to ensure D’s vote and the tie.

But pirate king A hasn’t become pirate king for nothing. He’s a craftily rational pirate and has the game aced: He ensures a 3/2 split in his favor by offering a gold piece each to C and E, which is exactly one more than they would get for throwing the king overboard.

1. Mahatma Gandhi. 2. Walt Whitman. 3. Fidel Castro. 4. Abraham Lincoln. 5. Jane Austen. 6. The Zodiac killer. 7. Jack the Ripper. 8. Charles Darwin.

In two dimensions, it’s impossible. Exactly one line has to cross one other. But imagine the houses and utilities placed on a 3-D shape like a donut. This allows you to connect the one tricky line, house to utility, by wrapping around the donut’s outer edge and reentering through the center (electricity to house #3 in this picture).

Ha! There is no solution! Did that hurt your brain? With prior knowledge of your opponent, you might be able to guess if he or she is likely to demand more or less than half the pot. But that’s the best you can do: guess.

This short test measures your conservatism. First add your scores for questions 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7. Then subtract your scores for questions 3, 5, and 8. The best way to interpret your scores would be in relation to those of other test-takers, but very generally, a score above 6 implies you are more conservative than not.

This short test measures your honesty. First add your scores for questions 2, 3, 6, and 8. Then subtract your scores for questions 4, 7, 10, and 11 (numbers 1, 5, and 9 are not scored). The best way to interpret your scores would be in relation to those of other test-takers, but very generally, a positive score implies honesty.

The number you picked is 7. Pretty cool, eh? Addition wipes your mind free of distraction, priming you to subtract 5 from 12.

No matter what cards he has, Jonathan will always be able to turn over two non-ace cards. Showing those two cards has no effect on the probability that one of his three cards is an ace. But most people can’t help but treat the remaining cards as equally likely to be an ace, and therefore they (incorrectly) calculate the chances of Jonathan’s hand containing an ace as one-third. So, very few wanted to switch hands with him.

The correct answer, of course, is to switch hands, earning the original three-to-five odds.

In game theory, a pure strategy is one in which you act in a certain way every time. There are two pure strategies in the Diner’s Dilema: expensive meal every time or cheap meal every time. Playing the pure strategy of the expensive meal means that after everyone eats phat, splitting the bill results in everyone paying exactly the price of the expensive meal (which we already said wasn’t worth it). But playing the other pure strategy (everyone orders cheap), you never “win” any utility over the baseline. Technically, these two pure strategies are equal: In both, you get what you pay for.

And so a mixed strategy might be best, with some people ordering cheap and others ordering expensive. The exact mix depends on how much individuals value the expensive meal (compared with its price), how many people are in the group, etc.

Did you think of a carrot? Yes, a carrot looks much like a downward-pointing arrow.

If you were playing mano a mano, the best strategy would be the pure one of war all the time. You would either tie (1,1) or win outright (3,0). You would forgo earning a long string of two-point peace/peace ties, but you would beat or tie your opponent. This is what Genghis Khan did. It’s what the Vikings did, too: you know, all that burning and pillaging.

But constant war works only until the surrounding countries get hip. And when they do, they team up to punish the aggressor. In the Vikings’ case, this team was called the Hanseatic League, which played a strategy that game theorists call the “provocable nice guy.” This strategy shoots “peace” the first round and then mimics the opponent’s actions every round thereafter. The majority of peaceful nations gain wealth through cooperation, while every round, the aggressor is attacked by the nation it attacked last time (a bit like many swallows worrying a hawk).

A refinement of the provocable nice guy is “provocable nice guy with a touch of forgiveness.” This adds an infrequent “peace” in the round after an opponent shoots “war,” and can break an escalating cycle of aggression.

The clock hands show it five minutes ahead.

If the entire clock is stopped in time, then it no longer exists in the present. Poof, it’s gone!

The hands remain unchanged but its existence skips ahead: you have to wait five minutes to see it.

This is just a bit tricky, so dig in:

Most people think that you originally have a one-third chance and that after seeing a goat in an open door, you have a half a chance and so you might as well stick with your original choice.

Most people are wrong. Imagine the three possible choices and the results of switching:

So switching results in a win two out of three times. A study of 228 people found that only 13 percent switched and that the vast majority of these did so thinking they still had a 50/50 chance.

Question #1: Second.

Question #2: Um, how can you overtake the last person?

Question #3: 4,100. (What, did you get 5,000? Check your math.)

Question #4: Mary. Duh.

Question #5: He opens his mouth and asks for it.

This short test measures your emotional intelligence. First add your scores for questions 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9. Then subtract your scores for question 7 (questions 1, 4, and 10 are not scored). The best way to interpret your score would be in comparison with those of other test-takers, but very generally, a score above 15 implies you are fairly emotionally intelligent.

Because every couple eventually has exactly one boy, if there are x number of couples, there will be x boys. Done.

Now imagine the number of girls:

Half the couples have a girl first, so x/2 girls are born in this first “generation.” The chance of having two girls in a row is one in four, so of the couples who have to try again, x/4 girls are born. The chance of having three girls in a row is one in eight, so x/8 girls are born. So the total number of girls is x/2+x/4 + x/8 + x/16, etc. Eventually this all adds up to one.

So the ratio of boys-to-girls in this country is one-to-one.