SECRETLY, WHEN Mr. Lobster was safe in his own house, and no one else could see him, he trembled quite a little in all his joints as he thought about his narrow escape. He had nearly gone too far on land and dried up there. In fact, he had gone too far. As long as there was nobody around to hear him, he admitted it. If it had not been for Mr. Badger, he would have been gone—just as the ugly old sculpin had warned him he might.

Mr. Lobster decided that he would not tell the sculpin about that experience. It seemed unnecessary. The sculpin certainly knew a great deal, but there had to be some things that Mr. Lobster knew that the sculpin didn’t, so that Mr. Lobster could meet the sculpin and talk to him and feel superior.

When he woke up bright and early the next morning Mr. Lobster thought at once of going in with the tide. Again he thought of the dangers of the land and of his narrow escape, and so he hesitated. But then he began to feel curious. He said to himself:

“You will never satisfy your curiosity if you let a little fright keep you at home. It is always the things away from home that you have to find out about. Home is where you come to think over things you’ve found out.”

Then he answered himself back: “But suppose you get too far on land and start to dry up. Maybe Mr. Badger won’t drag you to safety. And besides, think how much you know already.”

So he spoke up to himself very sharply, saying, “It is unworthy to be satisfied with what you know.” And he added in a low whisper to himself, so that he could hardly hear: “Besides, you know you are just as curious as you can be about the land, and you will never be happy until you explore it some more.”

So he went out of his house, wondering if it was too late to catch the 6:17 tide. He was determined not to run for it.

On the way he met the sculpin.

“You don’t seem to be in any great hurry,” said the sculpin unpleasantly. “Surely, if you had such a delightful time yesterday, you are going ashore again today.”

“I have been planning my excursion,” answered Mr. Lobster, which, he felt, was very near the truth. “I am leaving now. What a pity it is you cannot go ashore.”

“I wouldn’t think of it,” said the sculpin. “Fortunately, age has brought me good sense. But are you really going?”

“Yes, indeed,” said Mr. Lobster, now very pleased with himself, because he knew he had made the sculpin furious with envy.

“Probably for the last time,” said the sculpin in a gloomy tone. “There comes a day when the wanderer does not return.”

Mr. Lobster gave three tremendous tail-snaps and shot away. It was so depressing, anyway, just to look at the sculpin without having to listen to such dire thoughts. He wondered if the sculpin always had such unhappy ideas. Perhaps that explained why the sculpin was so ugly.

“Just for that, I shall think joyous things all day,” he told himself. “I never want to look like a sculpin.”

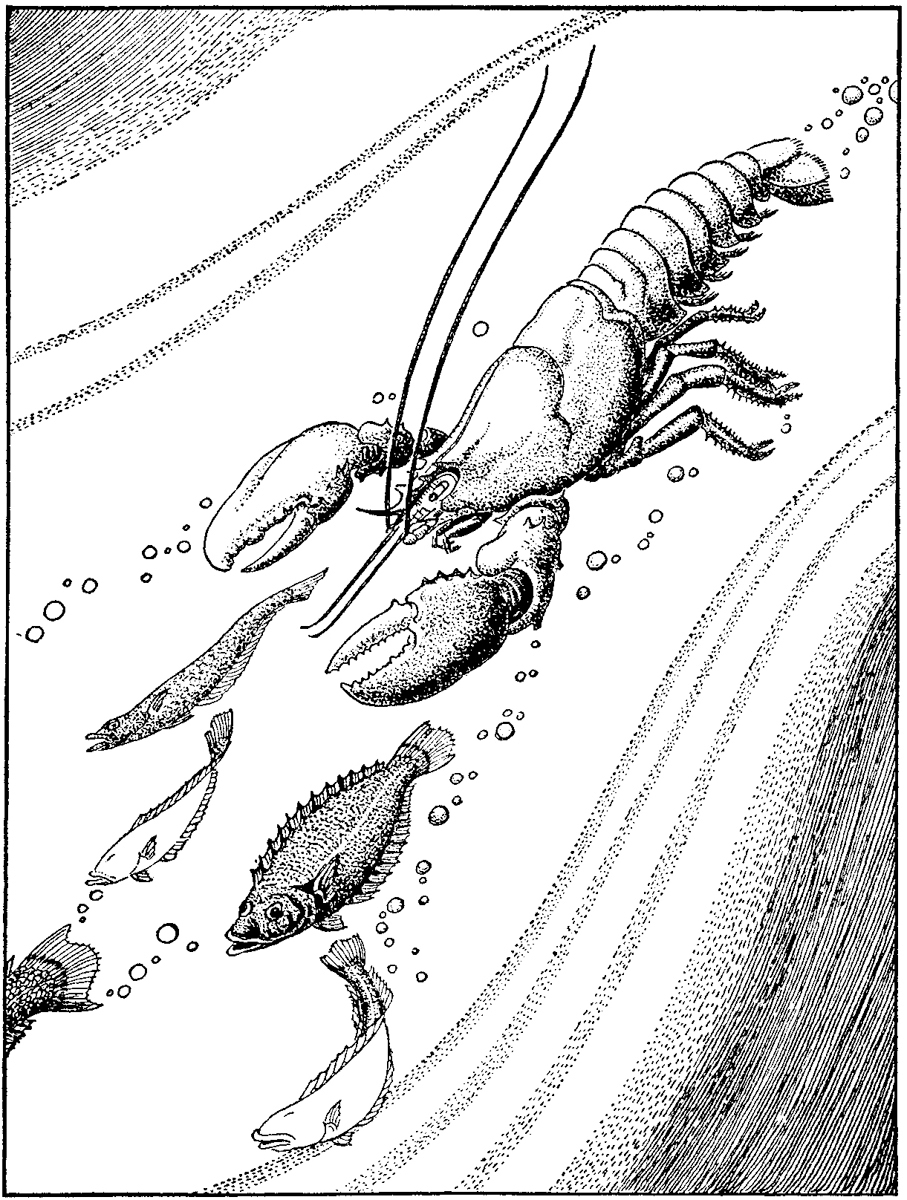

He had his first joyous thought just after he reached the river. There he saw that a great many small fish were going in with the tide, and he thought how joyous it would be to catch them and eat them.

“It will be a little late for breakfast, and a little early for lunch,” he explained to himself. “So I shall be eating between meals. Everybody knows that is joyous. In fact, I am sure that one of the best things about meals is to eat between them.”

And that was just what he did on his way up the river.

A GREAT MANY SMALL FISH WERE GOING IN WITH THE TIDE.

He kept a sharp look-out for clams without shells. When he found several all together he swam to the surface of the water, but there was a boat. So down he went and continued going along the bottom.

He noticed that the water in the river was dirtier than before, for there was brown in the green today; so he knew that it had been raining. Although he had never seen any rain, it had been explained to him years ago by a large eel.

“I shall find out about rain,” he thought. “One can never know too much. Evidently rain happens on land.”

Just as he was thinking this, and being very curious about rain, which was a second joyous thought, he came to another clam without a shell. He swam right up to the surface of the river and looked around, and there was Mr. Badger sitting on the bank.

“Well, good morning,” said Mr. Badger. “I say good morning, though it is really a very bad morning for fishing, because one must be polite. Couldn’t you bring a fish or two with you when you come in from the Ocean? Though of course, I am delighted to see you even if you bring nothing but yourself. Friends are people who don’t have to bring anything when they come to see you, aren’t they?”

“But I have brought six small flounders,” replied Mr. Lobster joyously. “Only they are under my shell, so to speak.”

Mr. Badger laughed.

“That is a fine joke,” he said, “but the next time please bring them in a paper bag so that I can count them. Will you come ashore? Let me give you my tail.”

Mr. Lobster went ashore, being very careful this time not to hold too tightly to Mr. Badger’s tail. He sniffed the air and was delighted to find that it was quite cool, for this was one of those summer days when the sun was resting, and the sky was down low over all the earth. Also, he saw with pleasure that there were pools of water on the meadow, which made the place seem very safe.

“I’ll never dry up today,” he said, “and I shall take time to look around and see everything. You know, Mr. Badger—”

“Oh, pardon me for interrupting,” said Mr. Badger with a twinkle in his eye. “But today I am pretending that this part of the meadow is Australia. That makes me in Australia also, fortunately; so I am no longer a badger. I am a wallaby. Just for today, I assure you, but I beg of you to take it very seriously. You see, if you don’t pretend seriously, there is no use pretending at all, and there is really nothing like pretending. You know, it is a great relief to me not to be a badger some days. But do continue. I am afraid I interrupted you.”

“I was going to say, Mr. Wallaby—”

“Oh, thank you, thank you, Mr. Lobster.”

“I was going to say that I must be careful not to walk too far, although I see that this meadow—”

“Oh, pardon me again,” put in Mr. Badger. “This is Australia.”

“I don’t understand at all,” said Mr. Lobster. “But let me see—this Australia has so much water on it that I am sure I am in no danger of drying up. These little pools are a very good idea.”

“Very good! Very good!” exclaimed Mr. Badger. “It has been raining today.”

“I was thinking of going for a short walk,” said Mr. Lobster.

“Very well,” said Mr. Badger. “I know it will make me hungry and I shall want to catch more fish than ever, but I will go with you. Just in case, you know.”

They walked slowly across the meadow. Mr. Lobster, who was looking as hard as he could, finally pointed a claw toward a hill at the edge of the meadow.

“There,” he remarked, “at the very edge of the meadow—”

“Pardon me.”

“There at the edge of the Australia,” began Mr. Lobster again, “is a creature standing perfectly still with his tail in the air. You can see it move, Mr. Badger.”

“I beg your pardon. Were you speaking to me?”

“I mean Mr. Wallaby.”

“Oh, yes, I hear perfectly now. Do go on.”

“You can also see its scales,” said Mr. Lobster. “It is an enormous creature, but I am very curious, and as soon as I can walk that far I shall go over there.”

“That is a tree,” explained Mr. Badger.

“Is it dangerous?”

“Oh, no, not unless it falls, and it only falls when there is a storm, and all sensible creatures stay at home during storms. So falling trees fall only on foolish and stupid creatures. So falling trees are good things. There, do you see?”

“I think so. I mean, I hope so,” said Mr. Lobster. “And I think we had better turn around now.”

“Very well. Besides, trees are not creatures, you know. They are only things. They were made for unimportant creatures like birds and squirrels to live in. Trees are not important.” Mr. Badger seemed very positive.

“Still, I want to see one close to. I am curious,” said Mr. Lobster.

“Some day you must come and see me. That is, when you have learned to stay ashore long enough,” said Mr. Badger pleasantly. “At present I am living in the woods. Somebody planted a tremendous number of trees in the woods. They are all over the place there. I suppose it was because there are so many birds in the woods. Of course, trees do give shade, but wouldn’t one know enough to stay home when it is too hot?”

That thought made Mr. Lobster feel a trifle too warm himself. In fact, he felt a trifle dry. He knew that he could stay on the meadow (which Mr. Badger said was now an Australia) for some time yet before he would be in any real danger, but he wanted to satisfy his curiosity about the rain. So he said to Mr. Badger, “Please excuse me for a moment, as I am going to try the rain.” And he crawled over and plumped himself into the biggest pool and took a good deep breath.

Immediately he gave a terrible tail-snap which made him come out of the pool backwards and land on the meadow right near Mr. Badger.

Then he tumbled over and sneezed four times. And each sneeze was so hard that it shook him down to the very last joint in his tail.

Mr. Badger tried to be polite, but he did love to laugh, and the sight of Mr. Lobster sneezing was so funny that this time he just laughed right out loud.

“I am furious!” exclaimed Mr. Lobster. “I might have been drowned! Why didn’t you tell me that was not water I was jumping into?”

“But, my dear Mr. Lobster, that is water,” cried Mr. Badger.

Mr. Lobster curled up his tail very tightly, which he did only when he was cautious or angry or when he was about to go somewhere at full speed. This time he was angry.

“I am sixty-eight years old,” he said, “and I guess I know what water is, having lived in it all my life. There is no salt in that pool. Therefore it is not water.”

Mr. Badger laughed so hard that Mr. Lobster tried to curl his tail even tighter. In fact, he was just about ready to crawl to the edge of the bank and fall in the river and go home.

But Mr. Badger finally stopped laughing.

“You really must pardon me,” he said. “But that is really about the best joke of all. You see, water has no salt in it unless you put it in. Somebody has put salt in the Ocean. Probably the same person who planted all the trees in the woods. I never dreamed that you did not understand that.”

Mr. Lobster let his tail uncurl a little.

“I forgive you,” he said. “I must say that it is a good thing somebody put salt in the Ocean. Otherwise I should live somewhere else.”

“Of course! Of course!”

“But I do think,” went on Mr. Lobster seriously, “that it would be a good thing if the rain were salted as well.”

“Oh, no doubt.” Mr. Badger nodded his head.

They were quite near the bank of the river by this time; so Mr. Lobster hurried over and fell in. Then he had a good swim, several long breaths, and got good and cool and wet.

Mr. Badger hung his tail over the bank.

“Won’t you come ashore again?” he invited.

“Well, just for a few minutes,” answered Mr. Lobster. “You notice that I did better today than I did yesterday.”

“I should say you did.”

When Mr. Lobster was ashore again, Mr. Badger said:

“I don’t know whether it is a pity or a good thing that I cannot see my tail. But I know that if this goes on long I shall lose all the hair out of it.” He was craning his neck, trying in vain to see his tail. “However, I do admire your courage, Mr. Lobster. I admire it because I have courage myself. That is how I know it is a good quality. If I find that you have the same opinions I have, I shall know you are perfect. But tell me, did you ever wonder why I come here fishing?”

“Why, no,” answered Mr. Lobster. “To tell the truth, it seems to me a very natural thing. Of course, everybody likes fish.”

“Oh, not at all!” exclaimed Mr. Badger. “Would you like to hear my story?”

Mr. Lobster wondered if the story would be so long that he would feel dry, but he was near the river, and he was curious. So he begged Mr. Badger to tell it.

“Well,” began Mr. Badger. “It is this way. Not all creatures like fish, strange as it may seem to you. Now I found out from an owl in the woods—”

“Excuse me, did you say an owl?”

“Yes. An owl is a very old bird who is so wise that he never goes out except at night, because he knows so much he cannot associate with other birds and has to go out when he will be sure not to meet them. And night is the only time. You can easily see how that would be.”

“Oh, of course,” agreed Mr. Lobster. “Do go on.”

“Well, the owl informed me that all badgers and wallabies and bandicoots and brocks, which I am, you remember, lived in burrows, that is, nice warm holes in the ground, and ate only meat. He said that they were never allowed to do anything else. Of course that made me furious. I had a fine burrow with a bed of dry leaves and hay; but of course I moved out at once, and since then I have lived under an old stump in the woods. It is a very unpleasant place. There is a good deal of noise from other creatures passing by, and it leaks when it rains. But of course I shall stay, since the owl said that I couldn’t.”

Mr. Badger drew a long breath of satisfaction. Then he continued:

“And then, when I realized that badgers were allowed to eat only meat I immediately decided to live on fish. It has been hard at times, for I hate fish, but I am glad to say I have succeeded. You see, I am independent, just as you are curious.”

“Is that being independent?” asked Mr. Lobster in some surprise.

“It is. The owl said I was contrary, but that is what other people always say when you are independent.”

“I see.”

“I lead a hard life in some ways,” Mr. Badger went on, “as you can easily understand. But I do not complain. Of course, one never complains about the troubles he makes for himself, such as eating fish and living in a miserable hole under a stump where the rain leaks in. Oh, no, I never complain, but right now I would like to eat seven pounds of meat and go to sleep in my own burrow.”

“I wonder if I am independent,” said Mr. Lobster.

“Of course you are. You live in the Ocean, and you want to be on land. When you are in one place and insist on being in another, that is a sure sign of independence—especially if you go there, as you do.”

“That pleases me,” said Mr. Lobster. “All in all, this has been a joyous day; I have learned so much. And you have no idea how much I have enjoyed your story. But now I must go home.”

With that he said “Good-by,” waved his right claw at Mr. Badger, and fell in the river.

On his way home he thought: “What a wonderful day! I have learned about a tree and an owl. I have satisfied more of my curiosity about the land. I have shown the sculpin that I am independent, for I have gone ashore again and am returning safely. Another thing—I have discovered that rain is not good at all, since it is nothing but water with the salt left out. Just wait until I see the sculpin!”