MR. LOBSTER rested for a long time, and when he woke up he felt much better than he had when he returned home from nearly being boiled. He remembered right away, however, that he had told the sculpin he was certainly going ashore again, and he realized that had been a rash thing to say. Right now he did not want to go ashore again.

And then he noticed that there were still some red places on his beautiful dark green shell, and he realized with sorrow that they would probably stay there until he shed his shell the next spring.

“I am not so very happy,” he said to himself. “I must therefore think a pleasant thought as soon as possible. Let me see. . . . Ah, when I shed this shell I shall be sixty-nine years old and my new shell will be number seventy. How fortunate I am to be able to shed my shell and get a new one every year. That’s more than the sculpin can do, and it is a pleasant thought.”

So, since it was a pleasant thought, and a superior one as well, he started the day by feeling better right then.

But he did not go out of his house at all, except to catch two small flounders who came to play in his seaweed garden.

In the afternoon he saw the sculpin come swimming up, and he immediately pretended to be sleeping. So the sculpin, being dignified, and therefore always polite, did not disturb him.

The next morning when he looked out, there was the sculpin again, moving his big fins slowly and staying right in one place.

“He is watching for me, and I have no desire to see him,” said Mr. Lobster to himself. “But if he does not go away I shall get hungry and have to go out. In fact, I am hungry now, come to think of it.”

He waited for quite a while, getting more and more hungry, until he felt actually hollow in a certain place under his shell. He looked at his shell to see if the red places were gone. No, they were still there. He knew the sculpin would say something unpleasant, but there was no waiting any longer. So he crawled out, looking just as pleased with himself as he could, which is the way to deal with stern and dignified people, but really not feeling at all pleased about those red spots.

“Well, well,” said the sculpin, “at last you have come out. I was really worried—deeply perturbed, I might say. I was afraid that something had happened to you and that you were not well. You know, you did look so poorly when you returned the other day.”

“Oh, not at all. Not at all,” said Mr. Lobster. “I am in fine condition. A person has to rest once in a while, you know. And I have been very busy these past weeks. It requires some effort to go ashore each day.”

“No doubt,” said the sculpin, without trying to look pleasant, which is the least he might have done. “But what has happened to your shell? I thought it looked strange the other day, and now I see that it is getting red! You really don’t look healthy.”

“That?” asked Mr. Lobster as though he were very much surprised at the sculpin’s question. “You mean that trifle of red? Don’t think of it. This shell is getting old, you know. I shall discard it in the spring.” He said this lightly, but he felt annoyed. The sculpin’s bright eyes saw too much sometimes.

Mr. Lobster decided to crawl right past the sculpin lest there should be any more annoying conversation to remind him of the unhappy meeting with Mr. Bear. So he started to go on without saying another word.

“Of course,” said the sculpin, swimming up very near, “now that you have had a rest, you are going ashore again at once.”

Now that was just what Mr. Lobster had been afraid the sculpin would say, and it was just the question he did not want to answer. It was strange how people of the dignity and wisdom of the sculpin always made the most unwelcome remarks when you did something which caused trouble just because you hadn’t followed their advice.

“At present,” Mr. Lobster answered sharply, “I am going to get my dinner.”

And with that, he tail-snapped away.

He did not go ashore that day. The next morning when he came out of his house to see if there were any pleasant creatures in his garden, who should come along but the sculpin.

“I wondered if you were going ashore today,” said the sculpin. “Because if you are, I’ll just go along a way with you.”

There was a suspicious look in the sculpin’s eyes.

“Not today,” said Mr. Lobster, and he started to move away.

“I see,” said the sculpin. “I see.”

Mr. Lobster did not wait to hear the sculpin say “I see” again. He gave two of his hardest tail-snaps.

But every day the sculpin came to ask him whether he was going ashore. Mr. Lobster didn’t know what to do. He wanted to go ashore just to show the sculpin that he wasn’t afraid, but he didn’t want to go because he thought of Mr. Bear, who might very well be on the beach. In a way, he wanted to see Mr. Badger, because they were friends; but in another way he didn’t want to see Mr. Badger for fear there might be more trouble.

After a few days Mr. Lobster was surprised to find that his curiosity was returning. He wondered what Mr. Badger was doing, and whether he could ever go into the woods in a pleasant manner, not being carried by Mr. Bear, and whether he could still get along all right out of water—and lots of other things.

“I suppose,” he said to himself, “that I shall be curious as long as I live, and I might as well face that fact. I wonder if anything cures curiosity. I really do want to go ashore again. And yet I am really afraid to meet Mr. Bear.”

He thought and thought and thought, and his curiosity got stronger and stronger. And then his wisdom came to the rescue. If he wanted to go ashore but was afraid to meet Mr. Bear, why not go to the river bank again, where Mr. Bear did not come? It was a wonderful thought.

This time when he met the sculpin he was glad to see him. “You are the gladdest to meet people,” he said to himself, “when you have nothing to hide from them.” And he spoke up quickly when the sculpin asked him if he was going ashore.

“Yes, I am,” he said. “It has been very nice staying here at home for a while. All travelers appreciate home, but of course I couldn’t live such a dull life all the time. It must be miserable not to be able to go ashore, and I don’t see how you stand it.”

The poor sculpin couldn’t say a word.

Mr. Lobster went in with the tide that day, but he did not hurry. In the first place, he stopped to catch several pleasant creatures on the way. In the second place, now that he was really on his way ashore again, he remembered the red places on his shell, and Mr. Bear; and he wondered just how wise it was to go ashore.

“After all,” he said to himself, “you should always think before you go into danger. It just does no good to think afterwards. Still, I am curious to know how Mr. Badger is, and whether the land is still pleasant.”

So he kept swimming until he came to the place where he used to meet Mr. Badger. Then he came up to the top of the water and looked around.

At once he saw Mr. Badger and at once Mr. Badger chuckled joyfully.

“Ha, ha! I knew you would come!” cried Mr. Badger. “I felt it in my bones you were safe. Come right ashore.”

Mr. Lobster went up the bank in the old way, hanging on to Mr. Badger’s tail.

“I am very sorry to have to use your tail again,” he said.

“Don’t mention it! Don’t mention it! You can pull all the hairs out of my tail if you want to on such a glad occasion as this. When old friends meet again for a reunion after great danger, such trifles as hairs don’t matter.” Mr. Badger seemed very happy. “Besides, you saved my life.”

“Oh, no,” protested Mr. Lobster, “you saved my life by knocking that kettle on the floor.”

“But you saved my life first by talking to Mr. Bear; so you really saved your own life.”

“But you saved my life yourself after I saved your life,” insisted Mr. Lobster.

“But I had such a good time,” said Mr. Badger. “I enjoyed teasing Mr. Bear. I always love a good joke, and it is such fun breaking things in a good cause. I did love to hear Mr. Bear’s window and dishes breaking. And you must admit that I couldn’t have saved your life if you hadn’t saved my life first.”

“Perhaps that’s true,” admitted Mr. Lobster. “It is a little confusing. I guess we’re even.”

“We are both heroes!” exclaimed Mr. Badger. “That’s what we are, and that is the important thing. It is delightful, isn’t it? And such a joke on Mr. Bear, who didn’t get either one of us! But you know, I did a very fine deed after you escaped.”

“Please tell me about it!” Mr. Lobster was curious at once.

“Well, it is all very well to have an enemy if he is a small enemy,” said Mr. Badger, his eyes twinkling. “It can be quite interesting. But when your enemy is as big as Mr. Bear it becomes a serious matter. So after you escaped and Mr. Bear went home, I went and gathered a great lot of fine corn and carried it to his door. I worked all night to get it there.”

“You did it at night—in the dark?”

“Oh, yes. You understand, it is the custom of badgers to go out only at night. We fear nothing. That is how I met the owl, and it was the owl who told me that badgers never went out in the daytime. Ever since then I have been out every day. You know, I told you the owl started all my troubles.” Mr. Badger sighed, but it was not an unhappy sigh, for he really loved trouble—so long as it was not as big as a bear. “Yes, I think it was very fine of me to return Mr. Bear’s corn.”

“Where did you get it?” asked Mr. Lobster.

“I stole it,” said Mr. Badger.

“Then you will have to return that also sometime, won’t you?” asked Mr. Lobster.

“Let us not go into that now,” said Mr. Badger. “The point is, I did a fine thing.”

“Well, anyway, you are very brave,” said Mr. Lobster.

“How brave we both are!” exclaimed Mr. Badger. “And what a happy occasion this is, to be together again. Two heroes—one a land hero, and the other a sea hero. And how lucky we are that our escapes were so narrow!”

“Pardon me,” put in Mr. Lobster. “Did you say ‘lucky’?”

“Of course. There is nothing in the world so delightful as to talk about the narrow escapes you have had. They are a great pleasure after they are all over.”

“I never thought of that,” said Mr. Lobster. “I see what you mean, though I myself am simply very glad my escape is over.”

They sat together on the bank of the river for a few minutes, very pleased with themselves. Mr. Lobster was especially delighted to realize that he was a hero who had had a narrow escape. And then suddenly he had an interesting thought which showed how wise he was.

“You know,” he said, “I have thought of another good thing. Each one of us has somebody else who knows he is a hero, and that is what really counts. I know you are a hero, and you know I am a hero. I suppose it is no fun at all being brave and a hero if no one knows but yourself.”

“Why, of course. What a brilliant thinker you are, Mr. Lobster!” Mr. Badger was happier than ever.

“And you also, Mr. Badger.”

“Oh, I beg your pardon, but not today,” put in Mr. Badger quickly.

“Not today?”

“Exactly. I mean I am not a badger today, though of course I am a hero. Once a hero, always a hero, is my motto.”

“Then you are a wallaby.”

“Oh, no, I was a wallaby before. Today I am a bandicoot. I must tell you why. You see, I knew that if the owl told me another thing I couldn’t do, I just wouldn’t be able to stand it. You see, now that I am eating meat again and living in my own house, I am quite happy. Well, the owl always calls me Mr. Badger; so now, whenever I go through the woods, I am a bandicoot. Naturally, when the owl calls out, ‘Good evening, Mr. Badger,’ I know he isn’t speaking to me because I am a bandicoot. And so I don’t have to answer. It is perfectly fair not to answer if people don’t know your name. As long as I don’t answer, the owl can’t tell me anything more I can’t do, because he can’t be talking to me.” Mr. Badger paused after that long explanation, looking quite pleased. “It is quite simple, you see,” he added.

“Perhaps it is,” said Mr. Lobster, “but I think it is very confusing. In many ways you baffle me. How am I going to keep you straight?”

Mr. Badger laughed out loud.

“It delights me to baffle people,” he said. “And think what a joke it is on the owl!”

Mr. Lobster did think of that, and he wondered what Mr. Badger would be tomorrow.

“Well, Mr. Bandicoot,” he began.

“Yes, yes, do go on,” said Mr. Badger, very much pleased.

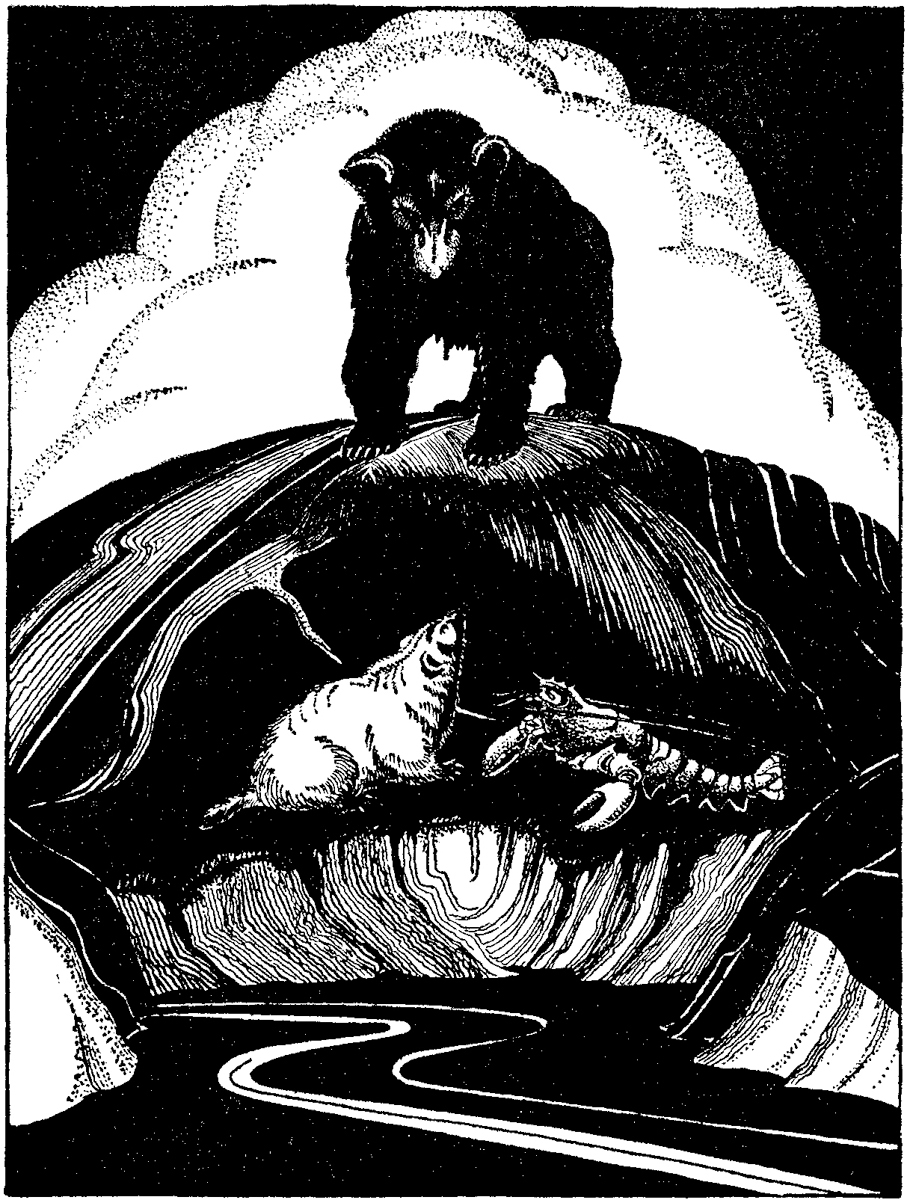

But just then came an interruption—a horrible interruption. It was a cough, a very deep cough that ended in a low growl. And it came from behind Mr. Lobster and Mr. Badger, because they were sitting on the bank of the river looking over the water.

Mr. Lobster trembled in every joint. He knew that he had heard that growl before.

Mr. Badger instantly stopped being happy.

Then they looked around.

There stood Mr. Bear, looking as big as a hill.

Mr. Lobster and Mr. Badger both started to move at the same time.

“I beg your pardon,” said Mr. Bear, in such a deep voice that Mr. Lobster’s tail curled and Mr. Badger’s hair stood up straight all down his back. “I didn’t mean to cough, and so the cough made me a little cross, and I growled. I tried to be very quiet.”

JUST THEN CAME A HORRIBLE INTERRUPTION.

For a moment the two heroes were silent.

Then Mr. Badger said, “I hate to swim, but I believe I will cross the river.”

And Mr. Lobster said, “I am feeling very dry. I really must be getting home.”

“Oh, no, please don’t do that!” exclaimed Mr. Bear. “I realized after I found the corn at my door that you were both so clever and so brave we all should be friends. Besides, you are both such good fishermen, and I love fish. I thought we could be friends and fish together.”

“But we can’t all be fish,” said Mr. Badger.

“I mean we ought to go fishing together.”

Mr. Lobster had been moving slowly backwards so that he could drop off the river bank into the water.

“Please don’t go, I beg of you,” said Mr. Bear. “It will make me very cross. I mean what I say about being friends. A bear is always cross but never deceitful. You know, you can trust cross people because they mean what they say, but you have to be careful of people who smile all the time.”

Mr. Lobster was so near the edge of the bank that he thought he could safely talk to Mr. Bear.

“Are you cross now?” he asked.

“I am furious,” said Mr. Bear calmly. “So you can believe every word I say.”

Mr. Badger’s back hair was lying down again.

“I feel better,” he said. “I am very independent; so it does my heart good to see people furious. But why are you furious now?”

“I have fished for hours on the beach and haven’t caught a thing.”

“I see,” said Mr. Badger thoughtfully.

“I am the largest creature in these parts, and I am the most civilized,” said Mr. Bear. “I had a window in my house until you broke it, and I fry much of my food. Now will you be friends? You know I am speaking the truth.”

“I know the window part is true,” said Mr. Badger, a rascally look gleaming in his bright eyes.

“I know a few things too,” said Mr. Lobster.

“Of course, you must realize that we are both heroes,” said Mr. Badger, still looking rascally.

Mr. Bear growled terribly.

“You both make me furious!” he exclaimed.

“Ah,” said Mr. Badger. “Then that settles it. We must be friends, because nobody but a friend can have the privilege of making one furious without suffering for it; and Mr. Lobster and I hate to suffer.”

“I should say so,” agreed Mr. Lobster, thinking of the red places on his shell, and the great heat that had caused them.

“Very well,” said Mr. Bear crossly. And he came and sat on the bank, unwound the fishing line which he had in his paw, and began to fish.

Mr. Lobster and Mr. Badger were not fishing, but they watched, and all three of them talked pleasantly, although Mr. Bear did not get any bites and so was very cross.

Mr. Lobster went into the river to get wet and to look around for fish. But there were no fish to be seen.

“Just my luck,” growled Mr. Bear. “It is always my luck to get places just too late. I shall probably be especially hungry today, too. I shall go home and eat blueberries for supper. I am very fond of blueberries, but you can’t fry them, and so whenever I eat them, no matter how good they taste, I feel uncivilized.” He began to wind up his line, growling softly to himself.

“I think,” said Mr. Badger, “that we had better plan some way of getting fish for Mr. Bear. Let us all meet here tomorrow and plan a fishing expedition.”

“We probably won’t get any, but I will come,” said Mr. Bear.

“And so will I,” agreed Mr. Lobster.

So Mr. Badger and Mr. Bear started home together.

“Good-by, Mr. Bear,” called Mr. Lobster, and then, “Good-by, Mr. Bandicoot.’ ”

“Thank you! Thank you!” called Mr. Badger.

“Now what did he mean by that?” asked Mr. Bear. “Was he calling names?”

Mr. Lobster did not wait to hear what Mr. Badger said, for he was sure it would be confusing. He just slipped off the bank, fell with a splash into the water, and started for home.

When he met the sculpin, just as he was getting near home, he said, “You know, there is nothing like going ashore. Such interesting and wise creatures there—and absolutely nothing to be afraid of.”

And he continued on his way, very happy indeed.