IT WAS a cold day along a certain river that winds through the meadows and comes down to meet the sea near a big cliff. All the meadow grasses and cat-o’-nine-tails were brown. The blackbirds and long-legged herons were gone, and all the small birds that make their nests in the deep grass. Only the tough old crows, shiny black and bright-eyed, flew over the river country. They didn’t want cold weather, but they weren’t going to leave home, even if it snowed and froze.

Near the sea and along the beach the gulls were just as busy looking for small fish and flying on white and gray wings as though it were summer time. For the gulls, like the crows, stay in the north in the winter time. But one old gull, who had seen a good many years and who had been studying the sky for some time, said to some young gulls who were near: “I feel very sure by the feel of the water on my toes this morning that we are going to have a hard winter.”

“What is it that will be hard about it?” asked a very young gull who had never seen a winter.

“Everything,” replied the old gull, “but especially the water in the river. And when the water becomes hard nothing comes floating down, like fish or turnips or other dinners, and so it is hard work to find food. Also, when the water is hard you can’t dive into it. Altogether that makes a hard winter.”

The young gulls decided to land on the clam flats and talk the matter over, and they went off with a good deal of noise.

Up on the hills and in the woods, where such creatures as Mr. Bear and Mr. Badger and the owl and the dormouse and the permanent partridge lived, a cold wind was blowing. It made a wintry sound in the sky, and a dry rattly rustle in the bushes and trees. The pine trees knew that they would be green, no matter how cold it got, so they didn’t care. The other trees were already red and yellow and brown, so that the sunshine made them beautiful; but they shivered. And the bright-colored leaves, tired of holding on to their branches, and cold in the chill wind, let go and fell to the ground.

In all that shore country, which is a very special country where things are different from city and town things, only the old ocean was unchanged. There it was, as blue as blue and reaching away forever to the edge of the sky. And when you looked at it you were glad that even if winter were coming the great water would still be there, and its waves would still come rolling in on the sandy beach. But if you put your foot in the water, or your hand, then you would know that something had happened since summer.

Now Mr. Lobster, who was known far and wide as The Curious Lobster, lived in that ocean. And he was therefore in it all over; so he was sure that something had happened.

Mr. Lobster was in his home under two big rocks at the bottom of the ocean not very far from shore. When he woke up on this particular day his long feelers shivered a little.

“I believe,” he said to himself, “that we are going to have the turn of the seasons. This house has been a very handy place because it is easy for me to get from here to shore, where I love to go, and it does not take me long to get from shore to home. And home should be a place not too difficult to reach. Home is too important to be far away. But I am afraid that I am living so near the shore that the change of seasons will bring cold water here, and I hate water that’s too cold. A wise creature always prepares for necessary changes, and since I am wise I must think about preparing. I may even have to move for the winter.”

It occurred to Mr. Lobster that he could think just as well if he were walking, and he might meet a pleasant creature, such as a small fish, which would serve for breakfast. So he left his home and his seaweed garden and crawled along the bottom of the ocean.

As he crawled he realized that he was quite hungry, and he began to look carefully about for dabs, flounders, perch, or stray clams. In fact, he looked so carefully and thought so hard about breakfast that he forgot all about the coming of winter and preparations for moving.

He made several very fast rushes, and he tail-snapped backwards with amazing speed for a lobster sixty-eight years old when he thought he saw a shark, so that, generally speaking, he felt unusually strong and well. And when he had met several pleasant creatures—to be exact, two dabs and two small flounders, he felt even better.

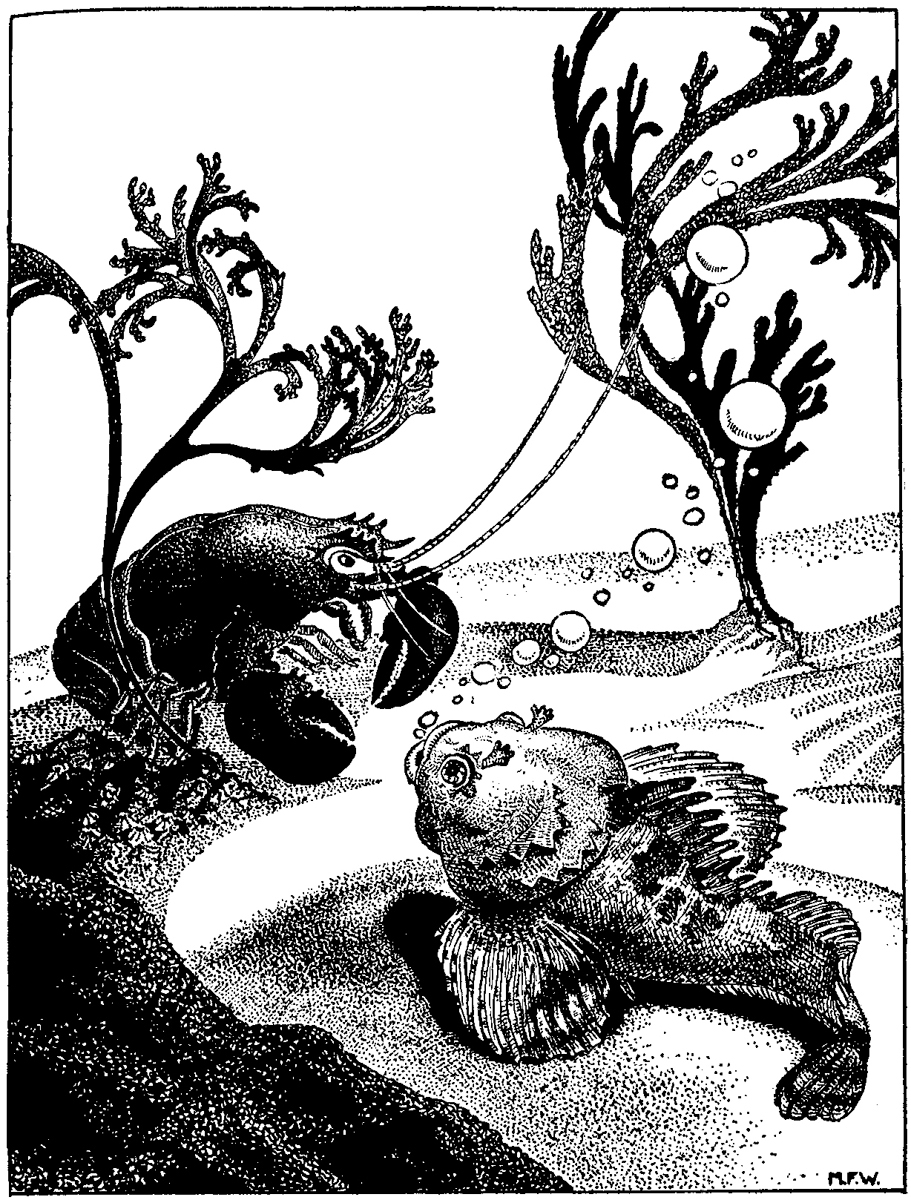

Just at the moment when he felt that it was not necessary to look for any more breakfast along came his old acquaintance the sculpin, looking extremely sulky, which made his ugliness even uglier than ever—and that is saying a good deal. For an instant Mr. Lobster had hopes that the sculpin was too cross to speak to him, because Mr. Lobster did not enjoy speaking with cross creatures. But the old fish came right up and, without the slightest courtesy, not even a good-morning greeting, said:

“Well, Mr. Lobster, it is a wonder you are not walking around on dry land this morning.” The sculpin had never gotten over the fact that Mr. Lobster had learned to go ashore, and whenever he thought about it he was angry because he could not go ashore, too. So the tone that he used now was not a pleasant one.

“Good morning,” said Mr. Lobster, who was too wise to be discourteous. “I am afraid I shall not be going ashore again for some time.”

“Afraid, indeed!” If the sculpin had had a nose he would have sniffed. As it was, he blew several impolite bubbles. “May I ask why, if you don’t mind talking with one who merely remains in the ocean where he is supposed to remain—and where you should remain?”

The sculpin did not say this in a humble tone. On the contrary, he was trying hard to be superior.

“I beg your pardon,” replied Mr. Lobster, “but I also consider the ocean my home. The mere fact that I have had many delightful times ashore with my friends this summer does not change my feeling about home. Home is the same, no matter where you go. The reason I shall not go ashore any more is that it is cold weather there now, and my friends, Mr. Badger and Mr. Bear, are no longer there to meet me.”

“Ah, so they have gone away.” The sculpin was actually pleased that Mr. Lobster’s land friends were gone.

“Well, you might say so,” said Mr. Lobster.

“I might? Now what do you mean by that?”

“They are not really gone,” explained Mr. Lobster. “They are hibernating.”

“Oh!” The sculpin was immediately unpleasant again—more unpleasant than ever. For he didn’t know what Mr. Lobster meant, and if there is anything superior creatures dislike, it is to find out that there is something they don’t know. So he scowled terribly; but he remained silent, as he did not want to ask Mr. Lobster to explain, which would reveal his ignorance. And then he waved his huge fins and sailed away without a sound. As he went, he stirred up a good deal of sand in Mr. Lobster’s face, apparently on purpose.

“AFRAID, INDEED!” THE SCULPIN BLEW SEVERAL IMPOLITE BUBBLES.

Mr. Lobster, now that he was alone again, dismissed the sculpin from his mind. He realized that he had not been thinking about preparations for winter at all.

“It’s strange,” he said to himself, “but when I am very hungry I find it hard to think about anything but eating, even if there are other important matters to be considered. I wonder if that’s so with all creatures.” And that thought made him curious to know what other creatures thought about it, and he wished that he could ask Mr. Badger, who always had an answer for any question. It made him sad to think that he would not see Mr. Badger again until spring.

While he was still being curious and somewhat sad, the sculpin came swimming back. He had decided that he would have to ask Mr. Lobster, after all.

“What is hibernating?” he demanded.

“Hibernating is sleeping,” answered Mr. Lobster politely, just as if the sculpin had also been polite. Mr. Lobster always pretended that other people were polite, for he had discovered that if only one person is impolite there is not much trouble caused by it, but if two people are impolite things are very difficult.

“Then why didn’t you say ‘sleeping’ in the first place?” snapped the sculpin.

“But it means sleeping all winter,” said Mr. Lobster.

“What! Night and day?”

“Yes.”

“And not ever eating?”

“Not eating a thing.”

“Then it is absurd, and I don’t believe it. If you did that you’d be gone.”

“Well, Mr. Badger and Mr. Bear do it all winter,” said Mr. Lobster.

“Then they’re gone, aren’t they?”

“Not really gone,” replied Mr. Lobster, “because they told me that they would be back in the spring of the year.”

“Nonsense, I should say!” This time the sculpin blew bubbles of satisfaction and superior knowledge. “You will see that they won’t ever come back. You can’t go all winter without eating and not be gone.”

Mr. Lobster straightened out the joints in his tail and shell so that he looked as big and important as possible. He was somewhat angry himself now.

“I am sorry to disagree with you,” he said calmly, “but my friends are both heroes, and heroes always tell the truth, and Mr. Badger and Mr. Bear both promised me that they would return. Besides, they have tried hibernating before, and they have always come back. So I guess they will this time.”

“Anyway, the whole thing is absurd!” The sculpin was surrounded by bubbles, and they weren’t pleasant bubbles either.

“Nothing a hero does is absurd,” declared Mr. Lobster. “And now I think I shall be going home.”

He gave an extra hard tail-snap, which left the sculpin yards away, and then turned and started for home.

As soon as he started he realized once more that he must think about moving. First his breakfast and then the sculpin had driven that really important matter from his mind. And he knew very well by the feeling of his shell and joints that the water was getting colder and that soon it would be altogether too cold for him. There was no doubt now that he must move out into deeper water for the winter. It was the one thing he had failed to consider in the spring when he had moved into the home where he now lived.

When he saw the two big rocks, which were such sure protection, and the lovely seaweed garden, which was such a delight to the eye, a feeling of real sorrow settled upon him. He was suddenly unhappier than he had been for a long time, a most unusual feeling for him to have just after a good breakfast. In fact, it was an unusual feeling for him to have at any time, for he was so curious that he was always trying to satisfy his curiosity. Of course that kept him busy and got him into adventures, and he usually had no time to be unhappy. As he had said to himself more than once, “In order to be really unhappy you have to sit down and think about it, and I haven’t time to do that, and I am too wise to do it, even if I did have time.” Which is just one of many things which show how wise Mr. Lobster was.

But now he was unhappy, and there was no denying it. “I love my home,” he said to himself, “and now I’ve got to move out. I wonder if there is anything worse than moving out of home. If there were only some way to avoid it . . .”

He went slowly past his seaweed garden and settled himself down inside his home to think. For a good many hours he thought and thought very patiently and very thoroughly. And then, when it seemed as though there were no more ideas left to think about, he had a wonderful thought.

“Hibernating is the thing!” he exclaimed. “If I hibernate I’ll be asleep, and I won’t know whether the water is cold or not. And I won’t have to leave home, because I can hibernate right here.”

And immediately he was happy.

“Tomorrow,” he told himself, “I shall go out and look for several pleasant creatures. Then, when I have eaten well, I shall come home and hibernate until spring. I shall be the first lobster ever to do such a thing. I wonder what it will be like. Already I am curious about it.”

The next day the water was even colder than before, but Mr. Lobster pretended that he did not notice it at all. He spent most of the day looking for pleasant creatures. Then, when the green daylight under the ocean began to fade, he hurried home. First he placed stones and sand in front of the entrance of his home to make a wall, so that it could be plainly seen that he did not wish to be disturbed. Then he climbed over into the most comfortable corner of his home, squddled down into the sand, and prepared to sleep.

All was dark.

“I shall hibernate until the water is warm and Mr. Badger and Mr. Bear come out again,” he said to himself confidently. And with that happy thought he went to sleep.

In the morning, when the sunshine coming down through the green water revealed his house and his wall and his seaweed garden as plain as could be, just as it did every bright morning, Mr. Lobster thought that he must be awake. A lobster, you know, never closes his eyes, even when he sleeps; so he could not help seeing things. In fact, at first, when he saw all the things he knew so well, he was greatly worried.

“No,” he said to himself, “I am not awake. I cannot be awake. I am hibernating, and so I must be asleep.”

And he did not move at all.

When the light grew brighter, and he could see each little leaf in his seaweed garden, and see how brown they were, now that cold weather had come, he said to himself: “I am asleep. I am asleep. I am hibernating for the winter.”

And he did not move at all, because he knew that if he moved he would be awake.

In the afternoon he had a feeling in a certain place under his shell, a kind of hollow feeling that he had known many times before.

“I am not hungry,” he told himself very firmly. “I cannot be hungry because I am asleep. And oh, how pleasant it is to be asleep for the entire winter. How pleasant to be in my own home instead of having to move.”

He had to say those words to himself a good many times, because the feeling under his shell was really not pleasant at all. Moreover, it seemed to be an unusually long day, so long that he began to wonder whether he could possibly sleep all winter long.

But finally the light faded and darkness came, and gradually everything was gone but the night.

The second day was even longer than the first, and much harder.

In the first place, not very long after the light came, several small fish just the right size for breakfast went swimming past Mr. Lobster’s front door. When he saw them the hollow feeling under his shell immediately became much worse than it had been the day before.

“If I did not know I was asleep,” he said to himself, “I should think I was good and hungry. But those fish must be just a dream. All that I see must be a dream, but I do wish it wouldn’t be so dreadfully real. I wonder what Mr. Badger does when he hibernates, and if he gets hungry while he is asleep, and if he has such dreams . . . Dear me, dreams can be so troublesome.”

In truth, Mr. Lobster was not happy, and not to be happy in your own home is to be miserable. So Mr. Lobster was miserable.

And then, to make things still worse, the water was much colder than it had been before, and the cold began to creep in between the joints of Mr. Lobster’s shell. His feelers were almost numb, and no matter how tightly he curled his tail, he grew colder and colder all over.

By the time night came he felt that he had passed the longest and coldest day of his life.

“I hope,” he said to himself, “that the beginning of hibernating is the worst, and that from now on it will be pleasant. How can it be so uncomfortable to be asleep?”

He was still firmly resolved to hibernate, but as he lay still and shivered in the darkness he was just a little afraid. He wondered if he might not starve or freeze before spring. It was a dreadful thought. But still he did not move at all.