My friends say, and I recognize the truth of it, that my hearing is not nearly as good when absorbed in astronomical work.

—Henrietta Leavitt in a letter to Edward Pickering

Although unmarked by a plaque, the second-floor room where Miss Leavitt and the other computers probably worked is still intact. The university, always pressed for space, hasn’t been as diligent about preserving the old observatory buildings as it has the collection of photographic plates. The wooden ceiling beams have been painted over in institutional white enamel. Fluorescent lights have been retrofitted where chandeliers once hung and an air conditioner mounted in one of the old sash windows. The place has all the charm of a room in a state hospital. Nearby a dumbwaiter, which shuttled the glass plates up from below, now holds a computer printer. A closet is crammed full of abandoned IBM Selectric typewriters, another archeological layer of cast-off technologies.

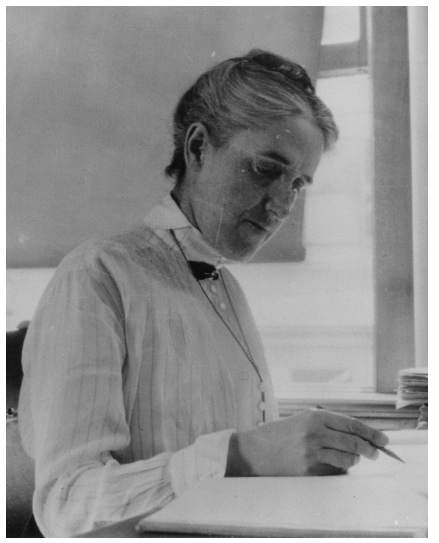

Haul off the junk, restore the late-nineteenth-century decor, and imagine Miss Leavitt, as she would have expected to be called, in a long frilled dress buttoned to the neck, her dark hair pulled tightly into a bun (we are extrapolating here from one of the only existing photographs). She is sitting at a table before a wooden viewing frame that supports a large glass plate—one of those black-on-white reversals of the night sky. At the base of the frame is a mirror, reflecting light in from a nearby window to illuminate the image from behind. Around her sit other computers, similarly occupied, and occasionally Edward Pickering drops by to see how the calculations are going.

Henrietta Swann Leavitt (Harvard College Observatory)

She was twenty-five when she arrived at the observatory in 1893 as a volunteer. Her goal was to learn astronomy, and apparently she was of somewhat independent means. The daughter of a Congregationalist minister, George Roswell Leavitt, Henrietta had been born on the Fourth of July 1868 in Lancaster, Massachusetts, to what once was called “good Puritan stock.” Her ancestry can be traced back to Josiah Leavitt of Plymouth, and to four centuries of Leavitts in Yorkshire, England.

At the time of the 1880 census the family was living in one half of a large double house, 9 Warland Street in Cambridge, near Pilgrim Congregational Church, at the corner of Magazine and Cottage streets. Reverend Leavitt served as pastor. The neighborhood was solidly middle to upper-middle class. The Leavitts’ neighbors included a piano tuner, a clerk, a police captain, a grammar school teacher, and a civil engineer, as well as a soda and mineral water manufacturer, a carriage manufacturer, and the owner of a plumbing company.

When he dropped in to take the census, the enumerator found Mrs. Leavitt, also named Henrietta Swan (her maiden name was Kendrick), tending to three of her children, George, Caroline, and two-year-old Mira. (It was the last year of her life. A few months later Mira was dead.) Eleven-year-old Henrietta, the eldest, and another sister, Martha, were away at school. Another brother, Roswell, had died in 1873, when he was fifteen months old; the youngest, Darwin, would be born two years later.

The household must have felt crowded. Henrietta’s aunt, Mary Kendrick, also lived there, as did a servant girl. Next door, in No. 11, her grandfather, Erasmus Darwin Leavitt, lived with his wife and a thirty-year-old daughter (the census taker noted that she had a spinal injury). They too employed a live-in servant.

The family valued scholarship. Henrietta’s father had graduated from Williams College and earned a doctorate in divinity from the Andover Theological Seminary. Like her grandfather, an uncle (Reverend Leavitt’s brother) was named Erasmus Darwin, perhaps after the renowned eighteenth-century physician and naturalist, the grandfather of Charles Darwin. The younger Erasmus, the second president of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, would gain national prominence for his design of the Leavitt pumping engine at the Boston Water Works’ Chestnut Hill station. He was also a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

A few years later the Leavitts moved to Cleveland, and in 1885 Henrietta enrolled at Oberlin College, taking a preparatory course followed by two years of undergraduate work. Returning to Cambridge in 1888, she entered Radcliffe, then called the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women. (One of her cousins, a daughter of Erasmus Leavitt, was in the same freshman class.)

The entrance requirements were strict. Every young woman was expected to prove her familiarity with a list of classics— Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and As You Like It; Samuel Johnson’s Lives of the Poets, William Makepeace Thackeray’s English Humorists; Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels; Thomas Gray’s poem “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”; Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice; and Sir Walter Scott’s Rob Roy and “Marmion”— by writing, on the spot, a short composition. There were also tests on language (“Translation on sight of simple [in the case of Latin, Greek, and German] or ordinary [in the case of French] prose”), on history (“Either [1] History of Greece and Rome; or [2] History of the U.S. and of England”), mathematics (algebra through quadratic equations and plane geometry), and physics and astronomy. In addition to these examinations on “elementary studies,” students had to demonstrate more advanced knowledge in two subjects—mathematics, for example, and Greek. The catalog noted reassuringly, “A candidate may be admitted in spite of deficiencies in some of these studies; but such deficiencies must be made up during her course.”

The only deficiency listed on Henrietta’s transcript was in history, which she had corrected by her junior year. Along the way she also took courses in Latin, Greek, the humanities, English, and modern European languages—German (her only C), French, and Italian—and in fine arts and philosophy. She didn’t take, nor was offered, much science: just natural history, an introductory physics class (she got a B) and a course in analytic geometry and differential calculus (an A). It was only in her fourth year that she enrolled in astronomy, earning an A–. Observatory Hill is just up Garden Street from Radcliffe, and some of the Harvard astronomers, supervised by Edward Pickering, taught classes there.

In 1892, shortly before her twenty-fourth birthday, Henrietta graduated with a certificate stating that she had completed a curriculum equivalent to what, had she been a man, would have earned her a bachelor of arts degree from Harvard. She stayed in Cambridge and the next year was spending her days at the observatory, earning graduate credits and working for free. Maybe her uncle Erasmus had pulled some strings for her. She stayed there two years.

No diary has been found recording what it was about the stars that moved her. One of history’s small players, her story has been allowed to slip through the cracks. She never married and died young, and it is only upon her death that we find, in an obituary written by her senior colleague Solon Bailey, testimony to what she might have been like as a woman:

Miss Leavitt inherited, in a somewhat chastened form, the stern virtues of her puritan ancestors. She took life seriously. Her sense of duty, justice and loyalty was strong. For light amusements she appeared to care little. She was a devoted member of her intimate family circle, unselfishly considerate in her friendships, steadfastly loyal to her principles, and deeply conscientious and sincere in her attachment to her religion and church. She had the happy faculty of appreciating all that was worthy and lovable in others, and was possessed of a nature so full of sunshine that, to her, all of life became beautiful and full of meaning.

Although the obituary didn’t say so, she was also deaf, although apparently not from birth. In her second year at Oberlin she had enrolled as a student in its conservatory of music. For her new calling, eyes were more important than ears, and perhaps deafness was an occupational advantage in a job requiring such intense powers of concentration.

2

Pickering, always happy to have a motivated volunteer, put her to work recording the magnitude of stars, a craft called stellar photometry. During a time exposure, brighter stars leave larger spots on a photographic plate, chemically darkening more grains in the emulsion. Size therefore is an indicator of brightness. Looking through an eyepiece, Miss Leavitt would compare each pinpoint against stars whose magnitudes were already known. Sometimes this information was displayed on a small palette marked with spots arranged and labeled according to magnitude. Shaped like a miniature flyswatter, the tool was called a “fly spanker.” When she was satisfied that she had gauged the brightness correctly, she would record the information in neat tiny writing on a sequentially numbered pink-and-blue-striped page in a ledger book initialed “HSL.”

Early on she was asked to look for “variables,” stars that waxed and waned in brightness like slow-motion beacons. (A few of the more interesting were to be found in a constellation she might have considered her namesake, Cygnus, the Swan.) Some of the variables completed a cycle every few days, others took weeks or months. Her job was not to speculate why. For a while it was thought that each variable actually consisted of two stars orbiting about a common point, periodically eclipsing each other’s light. More recent evidence indicated that the temperature (judged by the color of the starlight) rose and fell along with the brightness. That suggested that these variables were probably single stars that periodically flared and dimmed. The reasons for the pulsation remained obscure. This was before anyone knew what powered the stars, much less why the flame might not burn steadily.

In any case, the rhythms were imperceptibly slow and subtle. (Astronomers were surprised to learn later that Polaris, the North Star, which they had been using as their touchstone for measuring brightness, regularly varied in magnitude.) Only by measuring stars at various intervals through the year could one detect the variations.

Photography made that possible. With dense swarms of stars on every plate, it was impossible to check each one. To find likely prospects, a researcher would take two plates of the same region exposed at different times and line them up, sandwich style, one on top of the other. One image was the standard black-star negative produced by the camera. The other was a positive. Align them just so and they would cancel each other— except for the stars that had changed in brightness. They would look subtly different. A black dot surrounded by a white halo would mean, for example, that a star had brightened, its image on the plate expanding in size. If a star seemed particularly promising, more plates would be compared. (If necessary Pickering would order new ones from the astronomers.) Plate by plate, the computers would measure a dot as it swelled and receded, writing tiny numbers on the glass in india ink.

Henrietta Leavitt spent day after day doing this painstaking work, absorbing herself in the data with what one colleague later called “an almost religious zeal.” She wrote up a draft of her findings, then sailed for Europe in 1896, where she traveled for two years. We don’t know where or with whom.

She hadn’t forgotten about astronomy. When she landed back in Boston, she conferred briefly with Pickering, who suggested some revisions to her work. Then, taking the manuscript with her, she left for Beloit, Wisconsin, where her father was now the minister of another church. Because of personal problems, never really explained, she remained there more than two years, working as an art assistant at Beloit College. She must have found the work unsatisfying, for on May 13, 1902, she wrote to Pickering, apologizing for letting her research languish and for being out of touch for so long. She hoped he would let her resume her projects from Wisconsin.

“The winter after my return,” she explained, “was occupied with unexpected cares. When, at last, I had leisure to take up the work, my eyes troubled me so seriously as to prevent my using them so closely.” Her eyes were strong now, she assured him, and her interest in astronomy had not waned. She asked whether he might send her the notebooks she needed to complete her manuscript. “I am more sorry than I can tell you that the work I undertook with such delight, and carried to a certain point, with such keen pleasure, should be left uncompleted. I apologize most sincerely for not writing concerning the matter long ago.”

She also mentioned having some trouble with her hearing, worrying, a little oddly, that stargazing might make it worse. “My friends say, and I recognize the truth of it, that my hearing is not nearly as good when absorbed in astronomical work.” Cold weather seemed to aggravate her condition. “It is evident that I cannot teach astronomy in any school or college where I should have to be out with classes on cold winter nights. My aurist forbids any such exposure.

“Do you think it likely that I could find employment either in an observatory or in a school where there is a mild winter climate? Is there anyone beside yourself to whom I might apply?”

It seems from the letter that her hearing problems then were fairly mild—the first ailment she mentions is with her eyes. Yet one of the standard reference books, Dictionary of Scientific Biography, states that as early as Radcliffe she was extremely deaf—a misapprehension that has been picked up and recycled again and again.

She must have been delighted with Pickering’s response. Three days later, he offered her a full-time job. “For this I should be willing to pay thirty cents an hour in view of the quality of your work, although our usual price, in such cases, is twenty five cents an hour,” he wrote. If it was not possible for her to relocate, he would pay her fare for a short visit to Cambridge. She could get her work in order to take home to Beloit.

“I do not know of any observatory in a warm climate, where you could be employed on similar work,” he continued, “and it would be difficult to furnish you with a large amount of work that you could carry on elsewhere.” In any case, he noted, “I should doubt if Astronomy had anything to do with the condition of your hearing, unless you have been assured that this is the case by a good aurist.”

She gratefully accepted his proposal for a working visit to Observatory Hill. “My dear Prof. Pickering,” she replied, a few days later. “It has proved possible for me to arrange my affairs here so that I can go to Cambridge next month and remain until the work is completed. Your very liberal offer of thirty cents an hour will enable me to do this.” She planned to arrive around the time of Harvard commencement and to take up her job before the first of July.

En route to the observatory, she stopped in Ohio to visit relatives, encountering another of the family problems that seemed to punctuate her life. “The illness of a relative with whom I stopped to visit on my way to Cambridge is likely to detain me for some time,” she wrote to Pickering, adding that she might be waylaid for several weeks. “I am sorry for the delay, which seems to be unavoidable, but my face is set toward Cambridge and I hope it may not be very long before I can report at the Observatory.”

Finally, on August 25, she contacted him again from an address in Brookline, Massachusetts, where she was temporarily staying, announcing her arrival.

“It has been a disappointment to me that I have had to defer the beginning of my work for so long,” she wrote. “At last I find myself free to take it up, and expect to go to the Observatory Wednesday afternoon, arriving there between half-past two and three. If there is a time which will suit you better, will you please let me know either by letter or by telephone?” At first she could work only about four hours a day, but was hopeful that she would soon be able to give him her full attention. “I hope that this long delay has in no way inconvenienced you.” Whether Pickering was beginning to find these plaints a bit wearing has gone unrecorded. In the coming years there would be many more.

Working through the fall semester, she took winter break again in Europe. A letter dated January 3, 1903, finds her aboard the S.S. Commonwealth, a mail steamer for the Dominion Line, writing to Williamina Fleming about a misdirected paycheck. (Henrietta’s younger brother, George, who was living in Cambridge with Uncle Erasmus, now a widower, helped straighten out the problem.) A year earlier the shipping line had initiated winter Boston-to-Mediterranean service; so perhaps she was off with a friend to Italy, or the South of France. It is nice to imagine her on deck at night, bundled up to keep her aurist happy, looking up at the stars.