CHAPTER III

[ December 8, 1762 — Wednesday ]

AS far as Sir William Johnson was concerned, there was no occupation in the world so fraught with frustration as this business of being head of the Indian Department. It seemed that he was continually being pulled apart: by the Indians on one side and by Lieutenant General Sir Jeffrey Amherst on the other. There seemed to be no middle ground whatever where they could meet, and the fault lay not with the Indians but with that fool in military command — and he

was

a fool! No one but a fool could so confidently and consistently ignore the multitude of deadly warnings that were afloat; and no one but a fool could consider the Indians as not being dangerous when goaded too far.

With an exasperated, unintelligible grunt, Johnson read through George Croghan's report a second time and still found it almost beyond belief. Croghan reported first that Ensign Tom Hutchins had returned to Fort Pitt from doing some mapping on the upper lakes and he brought with him the disturbing intelligence that the western Great Lakes Indians were extremely uneasy and that there was evidence of French agitation among them against the English. Reports had it, though Hutchins himself had seen none, that war belts were circulating. Further, the Indians he had encountered were all in very great need and they had fully expected to receive gifts of ammunition and goods. As Hutchins had stated it in his report to Croghan:

They were disappointed in their expectations of my having presents for them; and as the French have always accustomed themselves, both in times of peace and during the late war, to make these people great presents three or four times a year and always allowed them a sufficient quantity of ammunition at the posts, they think it very strange that this custom should be so

immediately broken off by the English, and the traders not allowed even to take so much ammunition with them as to enable those Indians to kill game sufficient for the support of their families.

Croghan went on to say that practically on the heels of this report from Hutchins he had had a visit — late on the night of September 28 — from a Detroit Indian, a Huron. This Huron told him that while he had not been allowed to attend it, since he was not a chief, there had been a highly secret council held in June at the village of the Ottawa war chief, Pontiac. Both civil chiefs and war chiefs from a number of tribes had attended and it was whispered that there had been at this council, dressed as Indians, two French officers from the Illinois country. Croghan's informant had admitted he did not know exactly what was said, but he was certain a plot was being fomented against the English and that the French officers were urging the tribes into an uprising. The Huron also said that with his own eyes he had in June seen deputies with belts being sent to tribes in the Illinois and Ohio countries and that another council was said to be scheduled for September, which was probably being held right then, as he had seen numerous parties en route toward Detroit.

Then, as if this were not enough, two days later when Croghan mentioned this to a trio of Iroquois he trusted, they informed him that they knew of it and had heard the same from a Shawnee. This in itself was verified when one of Croghan's associates came in from a trading trip into the Shawnee country with the news that the Shawnees had received a war belt from the Weas and that the Weas had gotten it from the French at Fort de Chartres. Croghan reported that he had then immediately sent all this information to Amherst in the hands of an experienced express messenger, who was to return at once with the general's reply. The man had returned to Fort Pitt from New York in record time, but hardly with the answer Croghan had expected. Amherst had replied:

I look upon the intelligence you received of the French stirring up the Western Indians to be of little consequence, as it is not in their power to hurt us. They are without ammunition and they would not dare to anger us, for before a regular army the Indians are helpless.

Stunned beyond measure, Croghan had thereupon written this report to Sir William. It was obvious that George Croghan was entirely disgusted and Johnson's heart sank at the thought that he might lose the services of his most able assistant. Croghan had concluded:

The Indians are a very jealous people and they had great expectations of being very generally supplied by us, and from their poverty and mercenary

disposition, they can't bear such a disappointment. Undoubtedly the General has his own reason for not allowing any presents or ammunition to be given to them, and I wish it may have its desired effect, but I take this opportunity to acquaint you that I dread the event, as

I

know the Indians can't long persevere. They are a rash, inconsistent people and inclined to mischief and will never consider consequences, though it may end in their ruin. Their success the beginning of this war on our frontiers is too recent in their memory to suffer them to consider their present inability to make war with us, and if the Senecas, Delawares and Shawnees should break with us, it will end in a general war with all the western nations, though they at present seem jealous of each other. For my part, I am resolved to resign if the General does not liberalize our expenditures for Indian affairs. I don't choose to be begging eternally for such necessaries as are wanted to carry on the service, nor will I support it at my own expense. There are great troubles ahead. How it may end the Lord knows, but

I

assure you I am of opinion it will not be long before we shall have some quarrels with them.

Slowly William Johnson refolded the letter and pushed it to one side. The thought of an Indian uprising sickened him. Too long had he been close to the Indians not to realize their temper and what would happen if they set out on the warpath. He had seen it time and again — the misery, the atrocities, the paralyzing fear, the death and destruction. To know that one man had it in his power at this moment to prevent this from happening— or, for that matter, to allow it to happen — very nearly caused him to tremble, for that one man was General Sir Jeffrey Amherst.

Wearily, fearful that it would do no good, yet desperately hopeful that somehow, in some way, he might find the right words to open the general's eyes to the peril looming, Sir William began to write to Amherst. It was a long letter and it went again over the need to relax policy where the Indians were concerned and to provide them with the materials they so desperately needed. The continued holding back of ammunition from them was a very grave error; instead of preventing an Indian uprising, it would almost certainly precipitate one. The signs were all there that such an uprising was forming now, but there was yet time to avert it if proper actions would be taken swiftly. He continued:

. . .

and tragedy, your Excellency, is on the point of breaking. It is true that through your orders the Indians are now very short on ammunition, but this will not prevent their uprising. However short of it they are kept in peace, these Indians will not in war lack for ammunition, as they will certainly capture military supply trains in the woods and overrun depots where ammunition is stored. They will also find powder in the frontier houses they will overrun. Nor, your Excellency, can warriors used to living off the

woods be starved out by any blockade or strategic cutting of their supply lines. The forts on which the General relies to hold them back, if not captured, will simply be passed by and the warriors will cut off and destroy a number of families, destroy their houses, effects, and grain, all within the compass of a very few hours, and then return by a different route to some of their places of rendezvous. The surviving inhabitants, together with all those near them, immediately forsake their dwellings and retire with their families in the utmost terror, poverty, and distress to the next towns, striking panic into the inhabitants who then become fearful of going to any of the posts. Trade becomes at once stagnated, nothing can be carried to any of the posts without an escort and, unless 'tis a very strong one

—

which is not always to be procured

—

the whole may fall into the hands of the Indians. This picture of a state of a country under an Indian War, however improbable it may seem, will be found on due examination not to have been exaggerated.

Late into the night Sir William continued writing until at last he was drained. He signed the final sheet with a flourish, folded and sealed it and then placed it into a waterproof pouch. At the front door, curled up and sleeping on a rug there, he found his Mohawk messenger, Oughnour, and prodded the warrior with his toe. Dressed in some of Johnson's castoff clothing and with his hair grown long and tied in a small queue in back in English fashion, Oughnour looked far more like a Mohawk Valley settler than an Indian.

"Daniel," said Johnson, using the Mohawk's Christian name as the Indian came alertly to his feet, "this is very important." He tapped the pouch. "Carry it to the big general at the mouth of the Hudson, where you have taken messages to him before. Go as fast as you can. Wait for his reply and then come back safely."

Oughnour dipped his head once, took the packet and an instant later the door had clicked shut behind him.

[ December 10, 1762 — Friday ]

Well established now as the foremost English trader of both Fort Michilimackinac and Fort Sault Sainte Marie, Alexander Henry was rather pleased with his lot and the way things had gone for him. The nervousness over the potential danger his savage customers might be to him had gradually dwindled until now he was rarely bothered with it. All signs pointed to the fact that the Indians had indeed fully accepted the English now and were happy with the trade — or at least as happy as they could be when still being deprived of ammunition and liquor.

He had spent a large portion of this year at the home of Jean Baptiste Cadotte and they had become rather good friends; and since Cadotte, in

deference to his wife who could speak no French, preferred to converse in the Chippewa tongue, Henry had by now become quite fluent in the language, though he was still learning more of it every day.

Cadotte was something of an enigma. While he seemed genuinely pleased at the presence of Henry here and the reopening of trade, yet there was a side of the man's character which Henry could not seem to penetrate — an aloof reserve into which Cadotte retreated on occasion. On such occasions, Henry had several times discovered the Canadian staring at him in an uncomfortably penetrating manner; and under that gaze the young trader would experience a little inexplicable shiver of omen at his nape. It was not a pleasant sensation.

But then, on September 19, had arrived a small detachment from Fort Michilimackinac to regarrison Fort Sault Sainte Marie. Five soldiers under the command of a thin, sharp faced officer. This commander was Lieutenant John Jamet of the 60th Regiment, recently promoted from the rank of ensign, and a rather engaging young man with whom Henry got along well from the very beginning. The presence of the garrison here at the Sault was beneficial for Henry, as the soldiers were eager to buy various trade goods from him.

Beginning in early October the whitefish run began and for weeks Henry had been occupied with the Indians in the taking of them, spearing great numbers as they swam the rapids. Each of the fish, when caught, would be neatly gutted and then, with the head also removed, split in half down its length until within an inch of the tail. They would then be hung for drying on a rail resting on two forked sticks, the tails sticking skyward and the slablike sides hanging below and the raw meat exposed to the air. By the middle of October Henry alone had caught and dried over five hundred of the fish and, though he tried to sell some to the garrison, Jamet declined to buy. The young officer had shaken his head and wrinkled his nose.

"Never was much of one for eating fish," he told Henry, "even when they're good and fresh. But when they're like this," he indicated the dry fish with his thumb and made a sour expression, ". . . well, I'd hate to think of being stuck here all winter with nothing to eat but that. I don't think I'll have any trouble trading some of our liquor supply to the Indians for all the venison and other food we might need throughout the winter. Of course," he added hastily at Henry's look of surprise, "that's not something I'd like my superiors to know about. The general frowns on giving them liquor almost as much as he does about giving them powder and lead. But, what little I give them can't be of any consequence."

Henry had shrugged and simply sent several loads of dried fish by boat back to his store at Fort Michilimackinac for his assistant, Etienne Campion, to use in the trade. Now, with winter rapidly closing in and the navigation likely to close any day, Henry began to think about heading

back with the remainder of his dried fish to his more comfortable quarters at Michihmackinac — a nice frame house he had rented, standing on the lot beside that belonging to Charles Langlade. It had been a busy time for Henry here and he could do with a few weeks of rest and change.

He had fallen asleep almost instantly upon retiring last night and slept deeply until a few moments ago when shrill cries had penetrated from outside and caused him to sit groggily erect in bed. It was still very dark and he frowned, thinking he had been dreaming, but then the calls came again:

"Fire! It's on fire! Fire!"

He bolted to his feet, hastily dressed and then raced out of the door of his little house, which was fairly close to Cadotte's. The Canadian was already outside, silhouetted by the roaring conflagration which was sweeping through the commander's quarters and even now spreading to the barracks of the garrison. Soldiers, some only partially clad, had spilled out the door of the latter structure. It was their shouting which Henry had heard. The trader ran to Cadotte's side and grasped his arm. He pointed to the front of the commander's house, where the door was little more than a wall of flame, and shouted to make himself heard over the roar of the blaze:

"Jean! Where's the lieutenant? Is Jamet still inside there?"

Cadotte nodded and then shook his head sadly. "There is no way to get to him. He is lost. The fire started there," he pointed at the chimney of the soldiers' barracks, "and fell over onto the front of the officer's house. He couldn't get out."

Henry, familiar with the interior of the officer's quarters, shouted and waved to several of the soldiers to follow him and ran around to the other side of the building. There a small window, broken now, belched great volumes of smoke. For just an instant, Henry thought he saw a movement in the smoke. With the help of two of the men, both coughing and choking nearly as much as he, Henry smashed the crossrods of the window sash and thrust the upper part of his body inside. The heat and smoke were suffocating.

"Jamet!" he screamed.

“Jamet!

Where are you?"

A gagging, strangling cry reached his ears and the sound of shuffling. An instant later, one of Jamet's outstretched arms touched Henry's hand and the trader snatched it, then caught Jamet's wrist. With a strength bred of panic Henry lunged backward and literally pulled Jamet halfway through the opening. The officer was naked and large areas of his skin were burned and shriveled. Some of these tore free as he was dragged through the narrow opening and dumped to the ground outside.

Immediately, even while the soldiers were continuing to pull Jamet away, Henry was back at the window, leaning inside. He was blinded by the smoke boiling past him, gagging and choking, feeling desperately with outstretched hands for anything that could be saved. He

touched a small keg and with great effort managed to lift it up and carry it some yards off before slumping to the ground. It was a half-keg of gunpowder — a portion of the ammunition supply stored in Jamet's quarters.

An instant later there was a tremendous whooshing explosion as the powder still inside ignited. The entire roof of the burning house lifted and then disintegrated and the pieces flew off in great arcs of cometlike brilliance. Several large chunks struck Henry's own quarters and in a few minutes that place was engulfed in flames. Even the stockade was burning now and in a very short while one whole wall had collapsed. The soldiers were doing all they could to extinguish the fire and keep it from spreading, but their efforts were mostly useless. In less than an hour virtually all of Fort Sault Sainte Marie was destroyed. Only Cadotte's house had by some miracle been spared.

Henry watched his own quarters being destroyed, along with the soldiers' barracks. Everything he and they had was gone — food, clothing, ammunition, supplies, equipment. His face was blackened by smoke and his throat raw from breathing it. White lines channeled down his cheeks from the tears which ran from smarting eyes and he stumbled to the doorway of Cadotte's house and entered.

Jamet, moaning with pain, lay on Cadotte's bed, his bare legs and buttocks and back badly burned. The Chippewa woman who was Cadotte's wife was already carefully rubbing a thick coating of bear grease all over the injured man. Cadotte, standing by the bed, saw Henry and came over to him. He clucked his tongue and shook his head sadly.

"My friend, it does not look good. She will do what she can for him, but he is very badly burned. He may not make it."

[ December 31, 1762 — Friday ]

Pontiac had risen to a considerable height of power and influence during the course of last summer, gradually winning the support not only of many of the chiefs of his own Ottawa tribe, but those of neighboring and even distant tribes as well. Yet, there were still many who were reluctant to cast their lot with him, reluctant to take up the war hatchet against so formidable an enemy as the English without some good sign that they would emerge victorious. This was particularly true with the tribes close to Detroit, where the English strength was most evident in the Great Lakes country.

After the two secret councils, Pontiac had held smaller council after council with these nearby chiefs, assuring them that they would not be in this alone if they joined him. He told them that the Detroit Frenchman who was their good friend, Antoine Cuillerier, had told him that a messenger from the Illinois country — a man named Sibbold — had come to him with word that right now a large French army was being readied and would

be here at Detroit in the spring to help the Indians in their endeavor to drive out the English. Cuillerier, Pontiac declared, was one white man who could be trusted and since he said the French army was coming, Pontiac had no doubt of it. Further, the war chief promised the assembled Indians that there would come a sign, that in a manner evident to all, an omen of evil for the English would manifest itself. When it did, he told them, they must divorce themselves from the English and prepare to destroy them all at a given time.

Pontiac was no seer, no prophet, but he was a shrewd leader and he knew that somehow, some way, something was bound to occur sometime that could be construed as an evil omen for the English. He hardly expected the meteorological phenomenon which occurred on October 5, but he was swift to claim it as the manifestation of his prediction. On that Tuesday morning ugly black clouds hung low over the whole area. More and more dense they became until even the chickens of the Frenchmen around Detroit went to roost. It was very nearly like night and the fearful eyes of both Indians and whites were almost continuously directed upward.

At one o'clock in the afternoon the rain began and it was a rain such as no one here had ever before experienced. The rain was black. As if a great reservoir of ink had suddenly been released, the ugly liquid slashed downward in torrents, running off roofs in streams of black, turning the ground dark, collecting in black puddles in even

depression, staining the creeks and rivers and lakes with each drop. With the rain came an oppressive smell, similar to that of burning sulphur. It was so strong and offensive that it caused some people to gag and hold kerchiefs to their mouths and noses to breathe through. It caused the eyes to smart and tears to form in them.

84

To the majority of the English it was simply an unexplainable phenomenon. Some were uneasy about it, but most were merely curious or amused. Some of the soldiers caught the fluid in empty inkpots as it runneled from the eaves, determined to use it for ink, and laughing and joking about it.

To the Indians, however, the black rain was a very powerful omen, a foreboding of evil directed against the English. Pontiac, as much awed by the black and smelly rain as anyone else, was nonetheless swift to snatch up the opportunity and claim it as the sign he had predicted would come; and the Indians who had hesitated in giving their allegiance to him, now were very strongly swayed by the greatness of this Ottawa chief who apparently knew the future. Many now came and said they would do as he asked.

Pontiac immediately sent runners to carry the news of what had happened here to the far distant villages of numerous tribes and thus increase his renown and prestige. Other runners he held in readiness while under his direction a bevy of squaws worked night and day making numerous long, broad belts of red and black war wampum.

He called for another council to be held in late November and that one

was attended by representatives of no less than twenty tribes. This time there were no white men in attendance — neither French nor English. The council was held at Pontiac's village, only recently relocated on the narrow

Isle

aux Peches

65

— Fish Island — which was hidden from the view of the Englishmen at the fort by the bulk of the thickly wooded island called by the French

Isle aux Cochons

.

68

During the preliminaries before counciling began, medicine men of the various tribes made small fires and removed sacred objects from their medicine bags and mumbled odd incantations. They created magic protective charms out of rocks and twigs by urinating on them, drying them out over the fires and then passing them out to all who were assembled that they might be protected from evil beings who moved through the darkness.

On the fifth day before the council was to begin, Pontiac stained his body black and, naked, disappeared into the woods of the island in order to fast and commune with the Master of Life. Even as the medicine men continued their mumbling over more charms, Pontiac returned and walked among them as if he were possessed. The black stain still covered his body and though it was bitterly cold out and he was unclothed, he gave no sign of being discomfited. His eyes were filled with a feverish brightness and in his right hand he carried a tomahawk stained with vermilion.

As practically everyone watched, he walked to where a cedar post painted black had been sunk to stand upright to a height of six feet. He stopped before it and then, with a wild, incoherent cry he slammed the red tomahawk into it with such force that much of the head of the weapon was buried in the wood. Then he entered his longhouse, had his squaws repaint him in garish blue, red and white paints, attached a cluster of vermilion-stained feathers to his scalp, tossed a blanket about his shoulders and returned to the assemblage.

He moved among them wordlessly to his own place, sat down and quietly smoked a red clay pipe while a score or more Ottawa squaws passed out portions of cooked dog meat from platters to all in attendance except Pontiac. Though it was whispered that Pontiac had not eaten for five days, the chief showed no desire to eat now, but merely sat and puffed on his pipe without expression, the large crescent-shaped nose pendant of smooth white stone reflecting the light of the small fires.

At last, when the assemblage had eaten and smoked, Pontiac stood up again and then he began to speak. His voice was strange, deep and compelling, and they clung to his words. He told them that he had communed with the Master of Life and that he had seen a vision in which a great war eagle had dropped from the skies and crushed Detroit in its grasping talons. He talked to them, chanted to them, sang of his own prowess and exploits, hammered a litany of war into them until it spread to a raging fire in every warrior's breast; and one by one the chiefs in attendance had stood and

danced and chanted and then buried their own tomahawks into the war post.

All night they danced and pounced and sang until exhaustion overcame them and they slumped to the ground. Only the Hurons, of all the tribes in the Detroit area, were not fully in agreement. They watched as the Chippewas and Potawatomies, the Ottawas and Mississaugis, Miamis and Delawares and Shawnees sunk their hatchets into the post, but they themselves were split. Half of the Detroit Hurons under Teata — a band largely proselytized by Jesuits — and half of the Sandusky Wyandot Hurons under Orontony rejected the plea of Pontiac and walked out, returning to their village. But the remainder of the Detroit Hurons under Chief Takee and those of Sandusky under Chief Odinghquanooron accepted the belt and hatchet and struck the post. What this all boiled down to was that in the Detroit area alone, Pontiac had now become the head of an alliance of no less than four hundred and sixty proven warriors.

In the morning the messengers who had been held in readiness were given the completed belts of red and black beadwork in intricate design; they memorized the message they contained. They would take them to every tribe and village to the east of the Mississippi and north of the Ohio and west of the Alleghenies; they would sing the message of war and throw down the red hatchet that it might be picked up and ceremoniously driven into the war post; they would tell of the great and final prewar council which would be held on the fifteenth day of the Green Moon — April — on the banks of the River Ecorse near where it emptied into the Detroit River to the south and west of the English fort.

The messengers had gone and already, in these weeks that had passed since then, many had returned from their missions and almost without exception had reported to Pontiac that the hatchet had been picked up and the war post struck, the war belt accepted and the promise given to attend the great council on the fifteenth day of the Green Moon.

And now, to one of his most trusted messengers, Pontiac gave another long, wide belt of wampum woven with a maze of intricate red and black designs. It was a belt that was more than just a war belt; it was a belt that would heal an old wound and which would bind two former enemies together in alliance; it was a belt in reply to a belt of similar construction just received from a runner who had come directly from Chief Kyashuta.

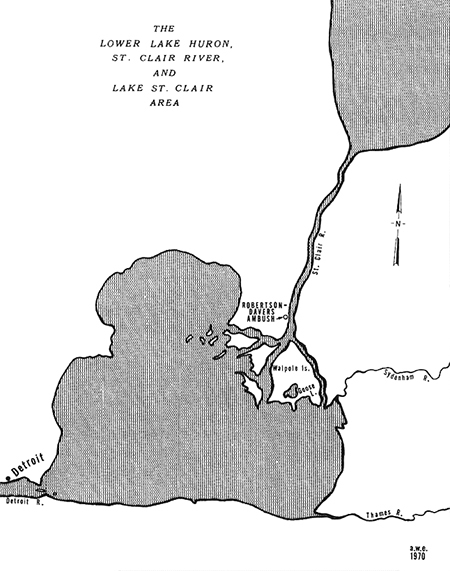

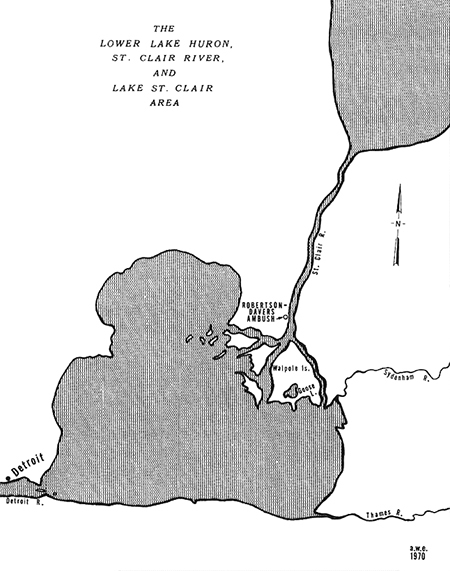

With a savage satisfaction, Pontiac watched his own messenger and the Iroquois messenger, each with his own small party, paddle away downstream on the Detroit River in two canoes. They would follow the river to its mouth and then continue southward and then eastward along the shore of the not-yet-frozen Lake of the Erighs — Lake Erie — until at last they came to the head of the Niagara River. Here they would conceal their boats

and strike off overland toward the upper reaches of the Genesee River to the village of Chenusio, seat of the Seneca government.

There, Pontiac had no doubt, the Chenusio Senecas under Chief Kyashuta would accept it — as he had already accepted Kyashuta's belt — and ally the Senecas to his new confederacy. They would help, when the time came, to destroy the English. And possibly — just possibly — that powerful Seneca chief might be able to persuade the entire Iroquois League to join in the uprising.

The dark eyes of the Ottawa war chief glittered at the thought.

[ January 24, 1763 — Monday ]

Captain George Etherington was a long, lanky sort of individual. He had joined the army a decade ago at the age of twenty and in doing so had found his niche. He was a reasonably good officer, though by no means outstanding. He followed orders well, commanded his men well, but rarely projected his thoughts to the future. He was content to accept things as they came. He personally did not like his command of Fort Michilimackinac any more than his predecessor, Lieutenant Leslye, now his second-in-command, had liked it. Etherington, however, would never consider complaining about it as Leslye had done. Long ago the captain had learned to accept without complaint whatever came his way in the military, knowing that eventually, whether he liked it or not, the situation would change. And anyway, things could always be worse. He could, for example, have been named commander of Fort Sault Sainte Marie instead of Michilimackinac, and it could have been he who was at death's door rather than Lieutenant Jamet.

Sitting at his desk in the little office preparing the monthly returns of his company — a copy each to be sent to Major Gladwin at Detroit and Colonel Bouquet, now in Philadelphia — Etherington reflected on what had happened at the Sault and shook his head. Poor Jamet was in a pretty bad way. Eleven days after the fire and explosion there, a messenger had reached Fort Michilimackinac with a letter from Jamet containing news of the disaster. And ten days after that — on December 31 — the entire garrison of Fort Sault Sainte Marie, with the exception of Jamet, arrived at Michilimackinac with more details, having completed the hazardous water journey to this post just in time, as navigation closed on the very next day.

Jamet, the returned soldiers told Captain Etherington, was too badly injured to be moved at the moment. He and the trader Alexander Henry were staying in the house of Jean Cadotte, the Frenchman. It was the only structure, other than the scattered wickiups and tepees of the Indians there, left standing after the fire. Since the lieutenant hadn't died of his burns in

the first few days, Cadotte was reasonably convinced that Jamet would recover. However, the young officer would have to do a good bit of recuperating before he'd be able to move about. With the barracks destroyed, there had been no other choice for Jamet than to send his men back to Fort Michilimackinac in the two remaining batteaux. He hoped to survive his burns and to follow the men himself before too long, when the lakes and straits had frozen over solidly enough to travel across on foot.

Again Etherington shook his head. From what the returned soldiers told him, Jamet was in a very bad way and they still doubted he would live, despite Cadotte's optimism, much less be able to walk the fifty miles or more through deep snow all the way to Michilimackinac. Etherington sighed and picked up his quill pen again, dipped it into the ink and began a letter to his regimental commander in Philadelphia:

Michilimackinac

24th January

1763

To

Colonel Henry Bouquet

Sir:

I have here enclosed you the monthly returns of my company to this day. On the 21st of December I received a letter from Lieutenant Jamet, who commands at the Falls of St. Marys, wherein he informs me that about 1 o'clock in the morning of the 10th of the same month, a fire broke through the soldiers chimney, which communicated itself directly to Mr. Jamet's house, where the provisions and ammunition were lodged. The latter prevented the soldiers at first from attempting to extinguish the flames, but in a little time the powder took fire and blew the roof off the house, after which the soldiers did everything in their power to put out the fire, but it was all to no purpose; for in less than an hour from the time that the sentry discovered the fire, one of the curtains of the fort, with the officers and soldiers barracks, was burnt to the ground, and all the provisions and ammunition entirely consumed; which obliged Mr. Jamet to send his garrison here, where they arrived safe. Mr. Jamet lost everything

he had in the world and made a very narrow escape for his life by getting naked out of a window. He is now, if alive, in a very miserable condition, being burnt to such a degree that he was not able to come in the batteaux with his men and is now at St. Marys without either coat, shirt, shoes or stockings; but as the lake is fast, I intend sending an Indian sleigh for him tomorrow. The other day I had one of my men killed by the fall of a tree. 1 am, dear sir,

Your most obedient, humble servant,

George Etherington

Captain Commandin

g

[ February 4, 1763 — Friday ]

Despite the parties and dances held every Saturday night, winter occupancy of Fort Pitt was hardly the most desirable duty. True, the new commander, Captain Simeon Ecuyer, a Swiss mercenary, was a rather lighthearted character and encouraged merriment and levity and casually overlooked numerous infractions of military discipline, but at best the social life at the fort was drab and the weekly dances only emphasized the routine sordidness of duty here.

The barracks were drafty and cold, the men plagued by lice during the day and by bedbugs at night, their tempers short and fistfights common. Sudden torrential flooding came and went from the Monongahela on one side or the Allegheny on the other, and the muck from it collected everywhere. The soldiers had to stay at the post because it was their duty to do so, but why anyone would remain here who was not required to was something of a mystery to every soldier. Yet the fort and the sprawling little town of Pittsburgh around it were crowded with settlers, trappers, Indians, scouts, schemers and drifters. On the whole, they were a coarse and rowdy lot, more often than not drunken and immoral and quite frequently criminals seeking to escape the law.

Some attempt at decorum was made by Captain Ecuyer, but it rarely succeeded. Inevitably he would have a gaggle of old women on hand to act as chaperons at the Saturday night dances, but theirs was a feeble effort at best. George Croghan, who vied with Ecuyer at being the life and wit of each of these sessions always made it a habit to quickly fill the glasses of these women, and fill them often, so that before half the night was over they could scarcely mumble their own names much less perform their charge.

The dances started modestly enough with a dozen to a score or more couples swirling to the tunes played by the garrison's musicians, but as far as most of the men in attendance were concerned, there were only three activities worth engaging in: drinking to excess, gambling for anything, making love with anyone. Liquor flowed in abundance and was consumed by the women almost as much as by the men. The debauchery usually began with toasting, and more often than not it was George Croghan who would leap up onto a chair and tower over the crowd, shouting out toasts and belting down a hefty jolt of liquor for each one. The toasting started innocently enough each time, with glasses raised and then their contents quaffed to such comments as:

"May the friend we trust be honest, the girl we love be true, the country we live in be free!"

"The heart of friendship and the soul of love!"

"Motherhood, friendship, and country!

"

"May we kiss whom we please . . . and please whom we kiss!" Gradually, though, as drink after drink was downed, the toasts became more ribald. Croghan, thrusting his glass high, would bellow such suggestive toasts as: "Days of ease . . . and nights of pleasure!" "Days of sport . . . and nights of transport!"

"May the lady of the night have crossed eyes, but never crossed legs!" Gales of drunken laughter would sweep over the assemblage at each toast and soon the couples would begin drifting off in search of quieter quarters for activities of a more penetrating nature. Captain Simeon Ecuyer was not at all backward in joining in such measures, nor was he particularly concerned over who knew about it. While well in his cups during the Saturday dance of January 8, he retired to his quarters with a very pretty young lady, and with both braggadocio and indiscretion penned a swift note to Colonel Bouquet in Philadelphia, telling him that:

. . .

thus, the prettiest ladies attend these dances and are regaled with punch; and, if that fails to produce an effect, whiskey. You may be sure that we shall not be completely cheated.

Of all the officers, soldiers and civilians connected to Fort Pitt, only three did not have regular Indian mistresses. Neither Croghan nor Ecuyer were of these three. The Indian women, mainly Delawares or Senecas, for presents of bright cloth or powdered paints or mirrors, would service any man and quite often they brought along daughters as young as only eleven or twelve to do the same. There was not an ordained minister at the post at this time and Sunday prayers were led by one of the local traders, but they were of little conviction and not only frequently interrupted by drunken hiccoughs, but tempered by each man's knowledge of the fact that the man who was delivering them was living with Fort Pitt's most prominent prostitute. The doctor hired by Croghan to look after his Indian employees seduced and impregnated the daughter of the blacksmith and then fought a duel with an officer of the Royal Americans over his right to her.

An air of hollow gaiety overhung all activities. It was as if each person there suddenly felt that his life would soon be over and now was the time to throw inhibition to the winds and do things which heretofore had only been shadowy, shameful thoughts. A common, undiscussed knowledge was in every man; a knowledge that before long, perhaps very soon, all hell was going to break loose on the frontiers again and that if anyone at all was to blame, it was none other than the commander of all the English military forces in America, Lieutenant General Sir Jeffrey Amherst. Indicatively, of all the multitude of toasts drunk at Fort Pitt, there had never been one drunk to him

.

Secure in the haven of his own quarters in New York, Amherst continued handing down directives which seemed to be deliberately calculated to offend and deprive the Indians. Croghan had pleaded with Amherst in letter after letter to alter his instructions for harsh economy, to ease up on the unbearable pressure he was placing on the Indians, to help alleviate the suffering being undergone by many of the tribes because they were being denied the very means of survival. Amherst continued deaf to all such pleas and Croghan became more and more convinced that the only sensible course for himself to follow was resignation of his office and a trip to London in an effort to get some measure of restitution for his personal financial losses in the handling of Indian affairs for the Crown.

And the prevailing impulse at Fort Pitt continued to be to eat, drink, and make merry . . .

[ February 10, 1763 — Thursday ]

Peace!

With the scratching of pens on parchment in the city of Paris this day, the war between England and France, which was already being called the Seven Years' War, was ended. The Treaty of Paris was signed and enemies in Europe had now become friends. The terms of the treaty were both noteworthy and audacious, for France had bought her peace by giving up to England what she had never owned in the first place.

By the dictates of the treaty, France now ceded to Great Britain all her territories in North America to the east of the Mississippi River, with the exception — by special provision — of New Orleans and its suburbs, from whence she declared she would continue to govern her immense Louisiana Territory.

And so now by this act, England not only had possession of Canada and the territory to the north and west of the Ohio River — the Northwest Territory — but also what she felt was the rightful ownership of the land and control of the inhabitants of it.

But Paris is a long way from the valleys of the Ohio and Mississippi and St. Lawrence Rivers. Sixty-five thousand French residents of Canada, plus several thousand more in the Michigan, Indiana and Illinois countries still knew nothing of this declaration of peace. Nor did the conquerors in residence — the English — know of it.

Nor did the Indians whose land it was.

[ March 16, 1763 — Wednesday ]

Ensign Robert Holmes, commander of Fort Miamis at the confluence of the St. Joseph and St. Marys Rivers, where these two substantial streams met to form the Maumee River, sat in his chair and tried hard to concentrate on the report he was writing to Major Gladwin at Detroit. Concentration

was difficult at best and his eyes kept deserting the paper before him and swinging to the bed where the bare-breasted Miami Indian woman lay outstretched, her dark eyes locked on him and waiting patiently. Her only covering was a loincloth, and even as his eyes met hers, she smiled and untied the waistcord knot, raised her hips slightly to free the material and then tossed the flimsy garment to the floor.

With herculean effort, Holmes turned his attention back to the report. Much as he wanted to put it off, he simply

had

to get this report written tonight to send off to Detroit with that damned war belt first thing in the morning. There might not be much to it, but then again it could be very important, perhaps even vital.

The last express from Gladwin had brought word that peace negotiations were in progress in Paris and that a cessation of arms had been called while the talks went on. The only problem here was that neither the French nor the Indians whom Holmes told about it in this area seemed inclined to believe it. The war belt was evidence of what they were thinking and feeling. Well, he would send it to Gladwin and that officer could be the judge of its importance. The major would probably talk it over with Captain Campbell and together they'd reach some conclusion and pass it on to the general.

A faint smile curled Holmes's lips as he thought of the general. What would that officer think if he could see Ensign Holmes now, writing an official report while not fifteen feet away an attractive, naked Indian woman lay waiting for him. He stifled a giggle. Amherst ought to know better than to order no friendly contact between his officers and the Indians. Men were only human, after all, and had fundamental hungers which had to be satisfied. Besides, rumor had it that even Major Gladwin had a little Chippewa filly to romp with, so why should Ensign Holmes be concerned?

Robert Holmes had first bedded with this Miami maid a couple of months ago. She was perhaps five or six years younger than he, which made her about eighteen, and the tanned coppery skin covered a body that was lithe and firm and showed no trace of the plumpness so common among many of the somewhat older women of her tribe. A rather striking angularity of facial features kept her from being truly beautiful, but she was indeed attractive and, as Holmes already knew well, extremely fulfilling. She had told him her name — Ouiske-lotha Nebi — but he was unable to pronounce it well and so he had simply called her by the first two syllables of it — Whiskey — and she seemed pleased with the nickname. During these weeks past she had virtually moved into his quarters, providing him not only a carnal release but also cooking meals for him and washing his clothing. In return, he provided her with food from the garrison's stores

and even gave her occasional pouches of powder and lead. After all, the poor devils had to hunt, didn't they?

As Whiskey made a slight noise behind him, he turned and watched with admiration as she yawned and stretched luxuriously, then turned on her side facing him and smiled again. Holmes swallowed and blew out a deep breath, averted his gaze reluctantly and began writing again hurriedly.

In the letter he explained to Major Gladwin how he had heard from an Indian — he did not mention that it was Whiskey who had told him — that a war belt had arrived and was circulating in the Miami nation. He told how he had then summoned Chief Little Turtle, the one who called himself Michikiniqua, who had come to him early this morning and readily admitted the truth of the rumor. The chief went even further; from a pouch slung over one shoulder he extracted the long, broad war belt and gave it to Holmes, saying that he had received it the day before from a party of Shawnees. It was a belt, Michikiniqua had said, that directed him to gather his warriors together and wait for a prearranged signal, at which time they were to rise and strike down all the English. But Michikiniqua, having always been far more inclined toward the English than toward the French, did not care to do so.

"This belt," he told Holmes, pointing to one end of it, "says to me, 'The English seek to become masters of all and will put all Indians to death. Brothers, let us die together, since the design of the English is to destroy us. We are dead one way or the other.' This is what the belt says at its beginning, and it says much more."

For nearly two hours Holmes had questioned Michikiniqua, until he was sure he had all the information. Then he directed the Miami principal chief to bring all his lesser chiefs into council so that he could speak with them, and this Michikiniqua had done. All afternoon Holmes had spoken to them and listened to what they had to say in return. It had not been until early evening that the council had ended and the Miamis had gone their own way.

Holmes had returned to his own quarters and mechanically ate the meal Whiskey had prepared for him and then started this report. Now he finished it with a flourish and quickly reread what he had written, to be certain he had left nothing out. After explaining to Gladwin how he came to acquire the belt and information, the ensign reported on the meeting with the chiefs and concluded with a transcription, as nearly accurate as possible, of what Chief Michikiniqua had said to him at the close of the council. He wrote :

I made notes as it was given and the following is a reasonably accurate copy of the speech of Chief Little Turtle

:

“My Brother, according to your desires and treaties with us I have consulted with our chief warriors in respect to this belt of wampum which you discovered to be in the village. We all think it best to deliver it to you so that you may send it to your general, though we were not to let this belt be known of till it arrived at Ouiatenon; and then we were to rise and put the English to death all about this place and those at the other places. This belt we received from the Shawnee Nation; they received it from the Delawares; and they from the Senecas, who are very much enraged against the English. As for the Indian who was the beginner of this, we cannot tell him, but he was one of their chiefs and one that is always doing mischief. And the Indian that brought it to this place was our Chief Michikiniqua, who was down at the council held in Pennsylvania last summer. We desire you to send this down to your general and George Croghan and let them find out the man who was making this mischief. For our parts, we will be still and take no more notice of their mischief; neither will we be concerned in it. If we had ever so much mind to kill the English, there is always some discovery made before we can accomplish our design. This is all we have to say, only you must give our young warriors some paints, some powder and ball and some knives, as they are all going to war against our enemies, the Cherokees."

I think, to the best of my knowledge, this is the contents of what was said at the delivery of the belt now sent. This affair is very timely stopped, and I hope the news of a peace in prospect will put a stop to any further troubles with these Indians who are the principal ones of setting mischief afoot. I send you the belt with this packet, which I hope you will forward to the general.

I am, Sir, etc.,

Robert Holmes

Ensign 1, B.R.A.R.

Commanding at the Miamis

True Copy and Endorsed of Indian Speech.

Satisfied, Holmes placed the folded belt of wampum atop the letter, ready for dispatch in the morning. He then lowered the lamp flame to a dim glow and turned toward the bed, swiftly stripping off his clothing as he went. By the time he reached Whiskey he was as bare as she and thoughts of Amherst or Gladwin or anyone else were suddenly very far away.

[ April 4, 1763 — Monday ]

Henry Gladwin, ever since taking command of Detroit, had made it a practice to meet with all his officers once each month to discuss anything that required attention and, in general, to learn the views of his subordinate officers. But the meeting he had called for today was not one of those

regularly scheduled affairs and a spark of uncommon interest was alight in the eyes of most of the young officers as they assembled.

Captain Campbell and Captain Joseph Hopkins entered together, conversing quietly between themselves, and they were followed by Lieutenants Jehu Hay and James MacDonald. Moments later a half-dozen more junior officers entered, with Lieutenant George McDougall in the lead. All took seats on the chairs provided and fell silent as they waited expectantly for the commander's opening remarks.

"Gentlemen," Gladwin began, "I have just received some reports which I would like to read to you and discuss. I would like to know your opinions in regard to their contents."

Gladwin raised a large black and red wampum belt from the desk and let it fall open. It was so long that although he held it near the middle over his head, both ends were still on the floor. He then bunched it together and placed it back on the desk and picked up a letter. It was the communique he had received, along with the belt, from Ensign Holmes at Fort Miamis. The assembled officers listened attentively as he read the letter, including Holmes's transcription of the speech made to him by Michikiniqua.

Without pause after he finished it, Gladwin put it down and picked up a second letter. "This one," he told them, "is from Lieutenant Jenkins, dated a week ago at Fort Ouiatenon, which I have just received. I read as follows:

Sir:

The bearer arrived from the post last Sunday, with two more deserters and his wife. They have not heard yet below of the cessation of arms, and I am acquainted by Monsieur La Bond that we have attacked or at least blocked up some place near the Mississippi; indeed, I don't well understand him, as he has an odd way of talking, but Captain Campbell will understand him better. Mr Hugh Crawford, the trader, acquainted me this morning that the Canadians that are here are eternally telling lies to the Indians, and tells me likewise that the interpreter and one La Pointe told the Indians a few days ago that we should all be prisoners in a short time

[and he adds parenthetically here]

(showing them when the corn was about a foot high) that there was a great army to come from the Mississippi; and that they were to have a great number of Indians with them, therefore advised them not to help us; that they would soon take Detroit and these small posts, and that then they would take Quebec, Montreal and all Canada and go on into our country. This, I am informed, they tell them from one end of the year to the other, with a great deal more that I cannot remember. I am convinced that while the French are permitted to trade here, that the Indians here never will be in our interest, for although our merchants sell them a stroud for three beaver, they will rather give six to a Frenchman. It is needless inquiring into the affair as the French had so much influence

over them that they will deny what they said, for the other day

I

had the express before me saying we should all be fighting by and by; but could make nothing of it as the Indians were afraid to own it before him, although the Indians that heard them talk of it stood to it. I am, Yours, et cetera.

That, gentlemen, is the end of Mr. Jenkins's letter. Now I would like your feelings in the matter. Do you think there is an actual plot afoot, or do you think this is all just so much talk calculated to keep us on the defensive?"

Donald Campbell was first to reply. He raised his rotund figure from his chair and straightened his wig slightly. "It seems to me, sir," he began, "that it may be a little of both. Certainly there is no doubt that the stories being fed the Indians that an army is coming to help them are lies. Yet, it appears that the Indians are beginning to put some credence in it. Though they have been very quiet lately, I feel sure I've detected a fundamental change in the attitude toward us recently. I have noticed a distinct coolness in them and there's a possibility that, acting on this misinformation, they may indeed be planning some sort of mischief. I've heard from some of the French here that Pontiac has been holding numerous councils and is gaining in prestige, but no one seems to know — or will

admit

to knowing — what they have been about. The general feeling is that he's stirring up the tribes."

Campbell paused and seemed about to say more when Captain Hopkins indicated a desire to comment and Campbell yielded to him.

"I agree," Hopkins said to Campbell, then addressed himself to the major: "Sir, I've heard a lot of reports that the French inhabitants here at Detroit —

some

of them at any rate — are growing continually more bitter at having to pay taxes for our support. They are angered, apparently, that they should have to help support with increased taxes, a garrison much larger than their own king had maintained here, and they complain that the outlying posts are always sending for more supplies. Men such as Antoine Cuillerier are said to be actively stirring up a heated resentment against us among the Indians and promising them with every breath that King Louis is going to send them help. They've passed the word that the report you gave out, sir, on the cessation of arms while peace talks are progressing, is a lie to hold them in check until we are ready to destroy them. The Indians believe them, but they're angry and frightened. At the moment they are quiet, but if they

should

happen to rise against us, we'll be in great trouble. The new policies have kept the tribes desperately in want, and yet they see here at Detroit and the dependencies goods worth in value somewhere around half a million pounds sterling, and they are envious. If only we could provide them with the gifts they are accustomed to . . .

"

Hopkins's voice dwindled away and he shook his head and sat down again, knowing it was unnecessary for him to finish.

"Unfortunately, Captain," Gladwin said, "our directives from the general are clear: we may not

give

the Indians anything. What they have need of, they can barter for with the traders, bargaining with the skins they have brought in. It is a policy we are required to uphold, regardless of our own personal feelings and whether or not we approve."

For over an hour they continued discussing the situation before finally breaking up. Gladwin returned at once to his own quarters and wrote a letter to Amherst, enclosing the wampum belt and the letters from both Holmes and Jenkins. Pointing out that the sum total of Detroit's defenses were three cannon — two six-pounders and a three-pounder — and several small mortars, along with one hundred and twenty-two men and eight officers, their position here was none too strong if the Indians decided to rise against them. The forty English traders and their engagees now at Detroit might be of some help in such a case, but this was offset by the likelihood that many of the French would either do nothing to help the English, or might even actively aid the Indians. Nevertheless, mentally crossing his fingers and praying he was right, he concluded the letter by expressing the opinion formed from his staff meeting today: that there was a general sense of irritation among the Indians near the dependency forts but that the affair would probably blow over, and that in the neighborhood of Detroit the Indians were perfectly tranquil, as they had been for some months. The Indians, he added, apparently did not relish the idea of the war between England and France possibly coming to an end, but that if he could have seventy or eighty medals to bestow on their chiefs as rewards and distinctions, he was sure they would be mollified.

In less than half an hour after Gladwin finished his writing, the packet for Amherst was on its way east by express courier.

[ April 27, 1763 — Wednesday ]

A sense of power such as he had never known before surged through Pontiac as he looked out over the great sea of faces before him, patiently awaiting his words which they had come so many miles to hear. Never before in the memory of any person present had so many Indians gathered at one spot to listen to the words of one man. Never before had one Indian had such influence among this many tribes as did Pontiac on this day and he was filled with an exultation and pride beyond anything previously experienced.

Seated on the ground before the little knoll upon which he stood were nine thousand warriors, representing at least two dozen tribes; and beyond them on both sides and at the rear were easily that many or more women and children. Perhaps eighteen or twenty thousand Indians were gathered

here and with the morning sun not yet halfway to its zenith, they waited patiently to hear the words of the war chief of the Ottawas.

This was the fifteenth day of the Green Moon and many of those in attendance had been traveling for weeks to arrive here for what promised to be one of the most important Indian councils ever held on the continent. For days they had been arriving here and as far as the eye could see there were hastily erected clusters of quonsets and wegiwas, tepees and wickiups, longhouses and cabins and various other types of shelters, while the air roundabout was filled with the bluish-white haze of smoke from a thousand or more campfires and nine times that many pipes.

The site Pontiac had chosen for this council was well selected. At his back as he faced to the north was the broad expanse of the Ecorse River and, in front of him, the broad grassy valley which so handily accommodated such an assembly.

87

Less than a quarter mile up-stream the Ecorse River split into north and south branches, and about the same distance downstream the watercourse emptied into the swiftly moving Detroit River at the foot of a nearly mile-long treeless island.

88

Most populous among the tribes on hand were the Chippewa, with about four thousand warriors, plus another thousand from the subtribe, the Mississaugi. The Delawares and Shawnees present from the Ohio country numbered six hundred and five hundred men respectively, while the Ouiatenons — also called the Eel River Miamis — had four hundred men here. The Miami and Potawatomi tribes were represented by three hundred and fifty men each and there were another three hundred each for the Hurons and Kickapoos, plus two hundred and fifty Piankeshaws. Another fifty men were on hand representing such tribes as the Seneca, Peoria, Fox, Muncee, Sac, Menominee, Mascouten, Sioux, Osage, Winnebago, Cahokia, Nipissing, Caughnawaga, Abnaki, Algonkin, and Kaskaskia.

The air quivered and thrummed with the muted sounds of ankle bells and rattling beads, pebble-filled gourds and shell horns, crude string instruments, small drums attached by rawhide thongs to the outer thighs, and smooth sticks of varying sizes tapped together to produce a wide range of tone. There was a pervading murmur of thousands of private conversations and soft laughter interspersed with raucous chatter from the squaws and children.

There were Frenchmen on hand, too — some of the most prominent Canadians from Detroit; men such as Antoine Cuillerier and his son Alexis and daughter Angelique, Mini Chene, Jacques Godefroy, two of the Campeau brothers, Baptiste and Chartoc, Pierre Cardinale, Thomas Gouin, and many others. They had been specifically invited here by Pontiac and had been escorted by a special squad of the war chief's men. They had all been shocked and more than just a little frightened by such an enormous gathering of Indians

.

Incredibly, though Fort Detroit was less than six miles distant and inhabited by no less than one hundred and thirty men and officers, not one Englishman was here at the Ecorse River. As a matter of fact, not a single individual of Major Henry Gladwin's garrison even suspected that such an Indian council was convening here. Secrecy had been maintained in exemplary manner and now guards were stationed on the perimeters to intercept and hold or turn back any Englishman, whether soldier or trader, who might accidentally come this way.

Over an hour ago a half dozen or more elderly Indian men acting as heralds under the orders of Pontiac, had wound their way through the makeshift shelters of the sprawling encampments calling in loud voices every so often that it was time to assemble for the council. And assemble they had, until now all were on hand who were expected and Pontiac stood before them, visible to all on the steep little knoll beside the river.

The crescent-shaped pendant hanging from his nostrils glistened whitely against the darkness of his skin and the swirling lines of paint and tattoos which decorated him. The loops of white porcelain beads hanging from his ears clicked softly as he moved his head back and forth, studying the assemblage. Broad beaten-silver bands were around both his arms just above the elbows and, from a silver disk an inch in diameter which was attached to his right temple, three eagle feathers — one bleached white and two dyed red — hung down and over his right shoulder. He was naked except for a loin cloth perhaps eight inches wide which hung to his knees in back and front, and a pair of soft doeskin moccasins upon his feet. Though not especially large in stature, he was nonetheless a commanding figure with a well-muscled body and stern, self-assured features. Around his neck and hanging down his sides so far that the two ends were on the ground was a broad belt of wampum, its black characters and symbols afloat in a field of deep red.

He raised both arms now and, as if by magic, a profound hush fell over the audience. His voice when he spoke was strong and far-carrying, audible clearly even to those farthest removed from him. Even as he spoke there came the murmur of many interpreters of the various tribes softly transposing the Ottawa tongue into that of their own people.

"Friends and brothers," Pontiac began, "it is the will of the Great Spirit that we should meet together this day. He orders all things and has given us a fine day for our council. He has taken His garment from before the sun and caused it to shine with brightness upon us. Our eyes are opened that we may clearly see; our cars are unstopped, that we may distinctly hear; our minds are open, that we may understand."

He paused and as the voices of the interpreters gradually died away after him, there came the rumble of a number of deep, guttural sounds of agreement and approval. When there was silence again, he continued:

"Friends and brothers, now do we know in our hearts

what the great antlered moose feels when he is pulled down in the snow by wolves, and his body devoured even before he is dead. Now do we know this, because now we are that moose and the wolves are the white men in red suits who call themselves Englishmen. They have worried us and kept us from our sustenance until we are become weak, and even now they crouch with tightened muscles, ready to spring and throw us down and devour us while still we live.

It shall not be!

"Brothers! These Englishmen are not as the French who are our friends. The Frenchmen wished to be our brothers, to live with us in peace, but not the English. No! The Frenchmen wished to do business with us and provide for us what we needed in exchange for what they wanted, but not the English. No! Yet now the French soldiers who protected us have been driven away and the English soldiers have taken their place and our lot grows unbearable. They take from us our land, our game, our forests, devouring them in great bites, always taking more than they can use and destroying that which is left; and when we request them to leave, they snap at us as will a mad dog snap at the hand of he who has nurtured and protected it. They deny us the means by which we survive. They are full of pride and they are constantly grasping for whatever they can reach, and there is no way by which we can obtain justice. Their highest general treats us with neglect and contempt, withholding from us those necessaries without which we grow weak, so that one day soon he may merely puff out his cheeks and blow us off the land. His officers in command of the posts on our lands abuse us, laugh at our misery, kick us away from them and call us names. When we come to their forts to council, we are made to state our business too quickly and then we are ordered away like little children whose minds are not complete and must be told what to do; and if we do not leave at once, we are struck by hard fists or the wooden ends of their guns until we run away for our own safety. Look at what they have done to us, my brothers. They have taken our game. They have taken our furs. They have taken our weapons. They have taken our pride and our self-respect. Still they reach out for more that they can take from us and only two things are left — our land and our lives — and now it is these they seek to grasp. They have swept away the French forever, so they think,

But such is not so!"

He stopped and pulled the wampum belt away from around his neck and held it high over his head in outstretched hands, turning from side to side several times so that all who were present could see it.

"Friends and brothers," he shouted passionately,

"it is not so!

This belt I have only recently received from an emissary of the French King, in token that he has heard the voice of his red children. It says that he has been asleep for many seasons, but now he is no longer asleep and his great war canoes will soon come up the big river of the lakes from the eastern sea, and he will pluck Canada back out of the English hands, and he

will lay against them a great punishment for their misdeeds against his red children while he slept. At this time the Indians and their French brothers will again fight side by side as they have always fought. We will then strike the English down as eight summers ago we struck down their strong arms under the General Braddock on the Monongahela when, as many of you who were there remember, we watched them walk up to where we were hidden and then we shot them down like empty-headed pigeons who are too slow-witted to flee. So again we will destroy them!"

There was a prolonged roar of approval punctuated by shrill war cries as he paused and several minutes passed before it became silent enough for him to continue. In the interval he glanced at the Frenchmen in attendance who were obviously very nervous. Before the meeting had begun, one of his chiefs who had helped escort the Frenchmen here had come to him. He reported to Pontiac that many of the French feared that an uprising, if it came, would be directed against all white men, including themselves, and they wished reassurance that this was not so. Now the war chief of the Ottawas directed his gaze toward them.

“The French," he said loudly, "have always been our brothers, and it is not necessary for brothers to fear brothers. I wish no harm to come to my French brothers here or elsewhere in this land. As a proof that I do not desire it, just call to mind the war with the Foxes and the way I behaved as regards you seventeen summers ago. When the Chippewas and Ottawas of Michilimackinac and all the northern nations came with the Sacs and Foxes to destroy you, who was it that defended you? Was it not I and my men?

"When Mackinac, then great war chief of all these nations, said in his council that he would carry the head of your commander to his village and devour his heart and drink his blood, did I not take up your cause and go to his village and tell him that if he wanted to kill the French, he would have to begin first with me and my men? Did I not help you rid yourselves of them and drive them away? How does it come then, my brothers, that you would think me today ready to turn my weapons against you? No, my brothers, I am the same French Pontiac who helped you seventeen summers before.”

69

Pontiac at this time handed the war belt to one of his chiefs sitting nearby and directed his gaze once again over the huge audience. Now that he had stirred their anger and resentment, it was time to appeal to their religious beliefs and superstitions. Some months ago when he had visited a Delaware village he bad listened to the words of an alleged prophet of that tribe who told of an encounter he had had with the Great Spirit. Not sure in his own mind whether or not he believed the story, Pontiac had nevertheless been greatly moved by the vocal picture the ancient Delaware had painted. Such a story, turned to his own devices, could be just what he

needed to weld the Indian nations together under his leadership. Word had already spread through this assemblage of the vision Pontiac had claimed to have had last autumn. It had laid the groundwork for what was to come now. Ten days before this council convened, Pontiac had made a show of mysteriously striking out into the woods in a straight line, his movements trancelike. On the ninth day he reappeared and hinted broadly of the great meeting he had just concluded with the most powerful deity, the Master of Life. Rumor of this flashed to every ear as the Indians had assembled here. Now Pontiac meant to profit from the seeds he had planted.

The Indian audience was sitting with quiet attendance, waiting for him to continue, and so he did, his voice still carrying clearly but filled now with a new and stirring tonal quality. He told them of how he had heard the Delaware prophet — noticing the Delawares in attendance nodding in support — and how he had learned from the old man the secret of direct communication and confrontation with the Great Spirit. He told them that he had then returned here and set about achieving a similar meeting. He now raised both arms until every eye impaled him, every tongue was mute.

"Friends and brothers," he continued, "let your ears hear well what now I have to say to you. As that Delaware Indian had, so had I a great desire to learn wisdom from the Master of Life. In order to find Him that I might learn from Him, I did as the Delaware prophet advised and took to fasting and dreaming and the saying of magical songs. By these means it was revealed to me that if I would travel straight ahead in a course as true as the good arrow's flight, I would in time reach the lodge of the Great Spirit. I told my vision to no one, but set out on my straightforward journey, having first equipped myself with gun, powder horn, lead balls, and a kettle for preparing my food. For some time I journeyed on in high hope and confidence.

"Some of you here," he added, "have told me that you witnessed my leaving, but I saw no one and heard nothing as I departed this place. On the evening of the eighth day of my travel I stopped by the side of a brook at the edge of a meadow and there I began to prepare my evening meal. Suddenly looking up, I saw in the woods before me three large openings and three well-beaten paths entering them. I was much surprised and my wonder increased the more when even after darkness had fallen the three paths were more clearly visible than ever. Remembering the important object of my journey, I could neither rest nor sleep and so, leaving my fire, 1 crossed the meadow and entered the largest of the three openings. I had advanced but a short distance when a bright flame came out of the ground before me and I

could go no farther. In great amazement I turned back and entered the second opening, and in a little while I encountered the same strange fire again and was forced to go back. Now, though afraid and

puzzled, I yet resolved to persevere and I followed the last of the three paths into its opening. On this I journeyed a whole day without interruption and at last, emerging from the forest through which the path had been winding, I saw before me a great mountain of dazzling whiteness."

Pontiac paused to give the straining interpreters time to catch up. As they did so, a satisfied murmuring arose from the assemblage who had been listening intently to his story. There was absolutely no doubt that they believed implicitly every word he was speaking.

"So steep was the climb, my brothers," the Ottawa war chief continued, "that I thought it hopeless to be able to go farther and I looked about myself in despair. My eyes searched the woods and the meadow and then the mountain and in that moment they stopped on a beautiful woman all in white who was seated some distance above. She stood up as I looked upon her and said to me thus: 'How can you hope to succeed in your design when laden as you are? Go down to the foot of the mountain, throw away your gun, your ammunition, your provisions, and your clothing; wash yourself in the stream which flows there, and you will then be prepared to stand before the Master of Life.' I obeyed her and began to climb among the rocks, but it was very difficult and the woman, seeing me still discouraged, laughed at my faintness of heart and told me that if I wished for success, I must make my climb using only one hand and one foot. After great effort and suffering, I at last reached the summit, but the woman had disappeared and I was alone. A rich and beautiful plain lay before me and at a little distance I saw three great villages far superior to the homes of my own people. I walked to the largest and hesitated before it, wondering whether I should enter. A man superbly dressed stepped out, took me by the hand and welcomed me to the abode. He then conducted me into the presence of the Great Spirit and I was awed to silence at the unspeakable splendor about him. The Great Spirit told me to sit and spoke to me thus: 'I am the Maker of heaven and earth, the trees, lakes, rivers, and all things else. I am the Maker of mankind, and because I love you, you must do my will. The land on which you live I have made for you, and not for others. Why do you suffer the English men to dwell among you? Your people, my children, have forgotten the customs and traditions of your forefathers. Why do you not clothe yourself in skins as they did? Why do you not use the bows and arrows and the stone-tipped lances which they used? You have bought guns, knives, kettles and blankets from the white men until you can no longer do without them. What is worse, you have drunk the poison firewater which turns you into fools. Fling all these things away and live as your wise forefathers lived before you. Take to you no more than one wife and do no longer practice the use of magic, which is a way of worshiping the spirit of evil. And as for these English, these dogs dressed in red, who have come to rob

you of your hunting grounds and drive away the game, you must lift the hatchet against them! Wipe them from the face of the earth and then you will win my favor back again, and once more be happy and prosperous. The children of your great father, the King of France, are not like the English. Never forget that they are your brothers. They are very dear to me, for they love the red men and understand the true manner of worshiping me. Go back now to your people, gather them together and those of other tribes and explain to them what I have explained to you. Direct them each tribe to rise as one in their own land and strike down the intruder of your lands who wears the red coat. Do not give him warning. Do not let him suspect. Catch him unawares and destroy him, and when you have done so, then you may discard his clothes and his weapons and his food and return again to the way of life that I directed for you in the beginning.' This," Pontiac added, "is what he said to me and then at once he was gone and the beautiful house and white mountain were gone and I was in the woods near here and returned to my village to tell my people what I had seen and felt and experienced and heard. I told them and now I have told you."

Abruptly his voice became harshly passionate again and his arms spread as if to encompass the whole of the assemblage. His body was shiny with perspiration and the flesh of his chest and thighs and upper arms quivered and trembled as if from a great chill and he appeared to be a man possessed.

"My brothers!" he shouted. "My friends! My children! Hear me now: we must now, from this time forward, cast out of us the anger for whatever ill has risen up between ourselves in the past. We must cast it away from us and we must let ourselves become one people whose common purpose it must be to drive from among us the English dogs who seek to destroy us and take our lands!"

There was a wild, shrill, thunderous roar of approval which grew in volume until the mind and ear were dazed by it; a fantastic, fierce, frightening, unforgettable sound which only gradually died away. Here was a man possessed of the Great Spirit. They could see it! Before their eyes the Great Spirit was using the voice of the war chief Pontiac to command them and a riotous blood-seeking fever swept through them. There was no need for Pontiac to ask them if they were with him. It was self-evident that they were. Fully five minutes elapsed before Pontiac found it quiet enough again to continue.

"Go now," he said to them. "Return to your homelands. Study the English in your lands and see how best to fall upon them and destroy them utterly before they can prepare to meet you. Deceive them! Let them accept you as friends and when the moment is right, strike them all in the same instant. Leave here at once, and when the word comes to you that