CHAPTER XII

[ August 26, 1764 — Sunday ]

COLONEL JOHN BRADSTREET wore a half-smile on his ruggedly handsome military face as the wooded shoreline of the Detroit River moved past on both sides. Soon they would be at Detroit where, he had little doubt, more laurels were waiting to be plucked. Obviously, from comments made at the Niagara Congress, there were still many bands of Indians in this area who, despite the actions of their brothers, had not made peace at Niagara. It was upon these that he would concentrate and, just as he had brought peace to the entire Ohio country and the far west, so now he would bring peace here.

His smile broadened some as he thought of the events of this campaign till now. He could visualize the stories already appearing about him in the eastern newspapers and he could virtually hear his own name on the lips of everyone as the word was passed of his grand accomplishments. Soon, perhaps, he would be getting dispatches from General Gage and he very nearly squirmed with anticipation of the praise they would contain. Perhaps — certainly it was not an impossibility! — he would return from this campaign to find he was advanced in rank to brigadier. After that, who knew what? Eventually there would be need for another military commander in chief in America; why not John Bradstreet?

There had been times, as his army continued westward along the south shore of Lake Erie after having left the Presque Isle area, that it had been impractical in the extreme for the Indian detachment traveling with them to continue afoot on shore as they had been, At such times they were wedged into the already crowded and leaking batteaux. It was quite uncomfortable. They could have kept pace on shore had Bradstreet slowed his pace a little, but this he adamantly refused to do. When, at one rest stop,

several officers came to him with a number of the chiefs in tow, he heard them out impatiently.

"Sir," one of the young officers asked hesitantly, "how are these Indians to get along, when the boats are too crowded and yet they can't keep pace on shore?"

"By God," Bradstreet snorted, waving them off with a disparaging motion of his hand, "let them swim and be damned, or let them stay and be damned!"

The fact that a number of the chiefs understood English well enough to follow perfectly what he had said concerned him not in the least. Whether or not they continued with his force made little difference to him.

Arriving at Sandusky, where his orders called for him to attack and destroy any Ottawas, Wyandots or Shawnees who appeared hostilely inclined, Bradstreet was met by a deputation of warriors who said they had been sent by their chiefs to beg that no attack be made against them, that they wished peace, and that if Bradstreet would continue to Detroit, they would meet him there in fifteen days and conclude a peace with him there. Again ignoring the advice of his officers that this was no more than a ploy to keep the army from destroying their villages, Bradstreet again entered into a preliminary treaty. He was not at all disturbed by the fact that the Shawnees and Delawares, with whom he had treated at Presque Isle, had not shown up here to surrender their prisoners as promised. After all, the army had traveled fast and he was certain they had merely been delayed, that they would soon be here to sec to that matter. Since Bradstreet himself would undoubtedly soon be back here too, there was no problem.

At the mouth of the Maumee River, the army paused again. Bradstreet had given much thought to the idea of ascending that river and moving westward into the Illinois country, but it was such a flagrant breach of his orders that he decided against it. He did, however, dispatch Captain Thomas Morris with an escort of Indians to go up the Maumee and down the Wabash, to make peace with each tribe he came to until he reached the Illinois country. Morris was selected because he could speak French, which Bradstreet assumed would be an advantage when the young, round-faced officer presented himself at Fort de Chartres to take over command of the place. He also gave Morris, as bodyguard, a Frenchman who was being returned to Gladwin at Detroit from Niagara. He had authority to hang the man but now told him that he would spare his life if he would go with Morris, interpret between the captain and the Indians, and take good care of the officer. Quite naturally, the Frenchman, expecting to be hung upon reaching Detroit, jumped at the chance. When Morris asked his name, he identified himself as Jacques Godefroy.

167

That sending Captain Morris and his party out on such a mission was an

extremely rash move of highly doubtful benefit, not in accordance with his orders, and subject to the sacrificing of this officer's life, did not seem to concern Colonel Bradstreet in the least. In the morning, having seen Morris's party off, the flotilla set out again for Detroit.

Now, as the Detroit River shoreline slid past, Bradstreet began writing a letter to General Gage. A private in the boat obligingly bent over to allow his back to be used as a sort of makeshift desk, steadying the inkpot with one hand and himself with the other. The colonel wrote proudly of what had occurred at both Sandusky and the mouth of the Maumee River, and then added:

. . .

and

I

will hold an Indian council at Detroit and intend to demand that Pontiac be given up, to he sent down the country and maintained at his Majesty's expense the remainder of his days.

The booming of a cannon and a great cheering smote Bradstreet's ears now and he looked up, then quickly put away his writing materials. Billows of white smoke puffed far in the distance from the walls of Detroit, followed moments later by more throaty boomings of the cannon as an excited welcome was given the approaching army, The ramparts were lined with soldiers cheering wildly and waving their hats,

It was precisely the sort of welcome Bradstreet expected and he was highly gratified. This, he reasoned, was only a sampling of what awaited him when he returned to New York.

[ August 27, 1764 — Monday ]

Rarely in his life had Colonel Henry Bouquet ever completely lost his temper. An extraordinarily levelheaded individual, he generally considered uncontrolled outbursts of anger as rather juvenile manifestations which accomplished little. When something came up which irritated him, it was characteristic of him either to do whatever was in his power to set matters right again or, if this was not possible, to accept the situation as philosophically as could be and look ahead from there. It was an admirable disposition which had gone far in contributing to his notable success as a leader of men. But there were exceedingly rare instances when an all-consuming rage gripped him. This day was one such time.

For the first two hours after receiving the impertinent, astonishing, and utterly unbelievable message from Colonel Bradstreet written from Presque Isle, he had been enveloped by a rage more blinding than any he had ever before experienced. Had Bradstreet been before him, he believed he could have gladly, and with malice aforethought, strangled the man with his bare hands. The nincompoop! The blindly ambitious unmitigated ass! Were not

matters on this frontier bad enough as it was without being hampered by the actions of an absolute idiot?

Little had gone as Bouquet might have wished since he had left Philadelphia at the time that the Niagara Congress was being held by Sir William Johnson. The force he had hoped to have available to take with him had been nowhere near the strength he had anticipated, and on his arrival at Carlisle on August 5 he had with him considerably fewer of the new provincial troops than were necessary, and his regulars were mainly the veterans of his battle at Bushy Run and Edge Hill a year ago.

Within five days after arrival at Carlisle, some two hundred of his provincials had deserted — some because they were afraid, others because they wanted to hunt Indians on their own and claim the high bounties being offered for scalps and prisoners, which they could not claim if they were in the pay of the province for such purpose. As a result, Bouquet had been forced to send an express to Colonel Andrew Lewis, commanding the Virginia Militia, and request two hundred of his men as volunteers to take the place of the deserters.

Supplies had not been available as they should have been and much of the gunpowder had been so damaged by persistent rains that it was worthless. The season was already extremely advanced to attempt still carrying out the Ohio expedition before winter closed in. Everything was chaotic and to this was added the continuing peril of red marauders all around them. The arrival of the army under Bouquet had done little to discourage the Indian war parties roaming this frontier. Five days ago, for example, insolently and within almost a stone's throw, six of Bouquet's men had been captured and killed. Throughout the whole countryside cabins were still being attacked and burned, their inhabitants butchered or led away as captives into the Ohio country.

Determining to carry on as best he could with what he had, Bouquet had led the army farther westward and it was today, at the tiny, disintegrating post of Fort Loudoun, that the express from Bradstreet had reached him. Not until three hours after he received it was he able to calm himself down enough to write in a still-trembling hand to General Gage:

Fort Loudoun, 27th August 1764

Sir:

I received this moment advice from Colonel Bradstreet which it is impossible for me to comprehend and which threatens our entire enterprise. He has treated with some Indians at Presque Isle the 12th instant and the terms he gives them are such as to fill me with astonishment . . . Had Colonel Bradstreet been as well informed as I am of the horrid perfidies of the Delawares and Shawnees, whose parties as late as the 22nd instant

killed six men, he could never have compromised the honor of the nation by such disgraceful conditions; and that at a time when two armies, after long struggles, are in full motion to penetrate into the heart of the enemy's country! Permit me likewise humbly to represent to your Excellency that I have not deserved the affront laid upon me by this treaty of peace, concluded by a younger officer

—

in the department where you have done me the honor to appoint me to command

—

without referring the deputies of the savages to me at Fort Pitt, but telling them that he shall send and

prevent my

proceeding against them! I can therefore take no notice of his peace, but shall proceed forthwith to the Ohio, where I shall wait till I receive your orders . . .

Completing that letter, he immediately wrote another, similar to it, to Governor William Penn in Philadelphia, stating the affair briefly:

Sir:

I have the honor to transmit to you a letter from Colonel Bradstreet, who acquaints me that he has granted peace to all the Indians living between Lake Erie and the Ohio; but as no satisfaction is insisted on, I hope the general will not confirm it, and that I shall not be a witness to a transaction which would fix an indelible stain upon the Nation.

I therefore take no notice of that pretended peace, and proceed forthwith on the expedition, fully determined to treat as enemies any Delawares or Shawnees I shall find in my way, till I receive contrary orders from the General . . .

Not trusting himself to write more, Bouquet signed and sealed the two letters and sent them off to Gage and Penn at once by express. Then, with his hands clasped tightly behind his back, he paced to and fro within his headquarters tent, trying to compose himself enough to sit down and write to Colonel Bradstreet. But in the end he gave it up, deciding that in his present frame of mind he would be unable to refrain from verbally crucifying John Bradstreet, as he would be more than pleased to do physically if that officer were here. In four or five days, he decided, when this all-encompassing wrath within him cooled, then he would write to the officer whom he now thought of as "that buffoon on Lake Erie."

[ August 31, 1764 — Friday ]

Behind him still, in the distance, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Gladwin could see the crowds of Indians and soldiers lining the banks of the Detroit River and the ramparts of the fort. Three cannon in succession belched smoke and flame and their rumbling roar swept past the schooner

Victory

and

reverberated down the river. At last — at long, long last! — he had been relieved of the command of Detroit and he knew beyond any shadow of doubt that he was looking at the fort for the last time in his life.

It was hard for Gladwin to remember any time over the past fifteen months that he had not felt perpetually weary, nor any time over the past nine or ten months when his thoughts and desires had not been more in England than here. And now there was a need, as well as a desire, for him to go home. Among the letters and dispatches brought to Detroit recently had been one for Gladwin from England bearing the sad news that his father had died and that Gladwin had been appointed executor of the estate. His presence was therefore required to attend to urgent matters.

He had made his decision and he meant to stick to it. Already he had requested and received permission to retire with his rank from His Majesty's service, and he wished with all his heart that the deck beneath his feet at this moment was, instead, that of the ship which would soon be carrying him to London and home. He was tired of everything: tired of war, of sieges, of Indians, of negotiations, of Frenchmen, of military life. Existence at Detroit these months past had become a monumental tedium which nearly drove him out of his mind.

What was in store for Detroit now, he had no way of knowing, but he was thankful that he would not be there to witness it. The extreme joy of welcoming Bradstreet and his army had quickly paled and in just this very short time he had come to dislike that officer intensely. As everyone else had been, he was shocked to learn what Bradstreet had done since leaving Fort Niagara. And the actions of the man since he arrived at Detroit were hardly conducive to inspiring trust and confidence.

One of the very first things Bradstreet had done upon arrival was to summon all the neighboring tribes to a council. The Chippewas were represented by Wasson, the only chief present who had taken an active part against Detroit during the siege. On hand to represent the Ottawas were Chief Atawang and Chief Manitou. Instead of the principal chief of the Miamis, Little Turtle — who called himself Michikiniqua — it was Chief Naranea who was on hand, and instead of Ninivois or Washee for the Potawatomies, the tribe was represented by Kioqua and Nanequoba.

Again in defiance of his orders, John Bradstreet now consummated still another treaty of peace, this time with all the Detroit area Indians who had not treated at Niagara. In the process of doing so, he clearly gave evidence of his total ignorance of Indian protocol, courtesy, custom, honor and pride. He tried to make a grand impression; and impression he made, though there was grave doubt as to how grand it was. He boasted of his prowess, of how he had brought the fierce Delawares and Shawnees into submission, of how he was the engineer of peace for this whole country. When, at one point, it seemed to him that the listeners were paying more

respect and attention to the Indian speakers than to him, he leaped to his feet and snatched a belt of war wampum that had been sent to Detroit by Pontiac and was being circulated among the tribes here. Before the incredulous eyes of all the Indians, Bradstreet proceeded to chop the belt to bits with a tomahawk — such an extreme breach of Indian parliamentary procedure that it was almost beyond belief to them that it had actually happened. Had they not witnessed it, they could not have believed it. He then demanded that the Indians present declare themselves to be "subjects of King George III," but there was no term for this in the Indian languages. The interpreters, already considerably upset themselves, improvised by telling the assembled Indians that they must now refer to the English King as "Father" rather than as "Brother."

168

When the council was terminating, the Indians,

as

straight-faced as possible, bestowed upon Colonel John Bradstreet an Indian name, calling him with seeming respect,

Peshikthi Matchsquathi.

He took it to be a great honor and carefully memorized the two alien words, while the interpreters, nearly bursting from containing their laughter, did not dare to tell him that it meant "The Timid Deer."

It was wholly without reluctance that Henry Gladwin had turned over the reins of command to his successor, Lieutenant Colonel John Campbell of the 17th Regiment. He wished him the best of luck with fervent sincerity and had immediately set about packing his things to go.

Some other matters of interest occurred before he left, however. The first was that on August 26, Bradstreet had organized a detachment of three hundred soldiers under Captain William Howard to head north and take possession again of Fort Michilimackinac. Among those nonmilitary people accompanying this detachment was a young trader who had joined Bradstreet at Niagara, intent on recouping his losses in the Michilimackinac area — a trader named Alexander Henry. Bradstreet also, by promising a payment of fifty cents per day per man — which he had absolutely no intention of ever paying — was able to raise two companies of fifty Frenchmen each from among the Detroit inhabitants to escort the detachment to that place.

169

Another thing Bradstreet did was to send the former commander of Fort Sandusky, Ensign Christopher Pauli, back with a small detachment to where the fort had been, there to establish a new post and to meet the Shawnees and Delawares who were due to arrive with their prisoners to be liberated.

Finally, at nine o'clock yesterday morning, John Bradstreet had assembled all the inhabitants of Detroit over fourteen years of age and made them renew their oaths of allegiance to the King of England.

Now, as the schooner coasted around a bend in the river and be could no longer see Detroit, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Gladwin turned away from

the rail and went to his cabin. There, propped against a lamp, was a little note written by the captain of the ship in a precise and flowing hand:

Sir:

It is a great pleasure having you aboard. I have the honor to inform you that upon reaching the harbor at the lower end of Lake Erie, this vessel, the

Victory,

is to be rechristened and will thereafter be officially known as the

Gladwin.

[ September 2, 1764 — Sunday ]

The fury of Major General Thomas Gage at his New York headquarters was hardly less than had been Henry Bouquet's. The commander in chief had just received both the letter from Bouquet and the letter, report, and preliminary treaty copy from Bradstreet. That one of his two principal field commanders should so blatantly thwart his orders and act in the manner Bradstreet had acted was unthinkable. Yet, here was the evidence of it, in his own boastfully written words.

Unlike Bouquet, Gage had no hesitancy about writing to Bradstreet. His pen flew across the page in line after line of bitter denunciation and chastisement. For nearly an hour he wrote, filling page after page, and then finally he concluded with a stinging reprimand:

They have negotiated with you on Lake Erie, and cut our throats upon the frontiers. With your letters of peace I received others giving accounts of murders, and these acts continue to this time. Had you only consulted Colonel Bouquet before you agreed upon anything with them (a deference he was certainly entitled to, instead of an order to stop his march), you would have been acquainted with the treachery of those people, and not have suffered yourself to be thus deceived, and you would have saved both Colonel Bouquet and myself from the dilemma you have brought us into. You concluded a peace with people who were daily murdering us. Your instructions called for you to

offer

peace to such tribes as should make their submission. To

offer

peace, I think, can never be construed a power to

conclude and dictate the articles of peace,

and you certainly know that no such power could with propriety be lodged in any person but in Sir William Johnson, his Majesty's sole agent and Superintendent for Indian Affairs. I again repeat that I annul and disavow the peace you have made!

[ September 17, 1764 — Monday ]

The Captain Thomas Morris who staggered into Detroit this day was a far cry from the neatly dressed, enthusiastic young officer who had been

dispatched westward toward the Illinois country at the mouth of the Maumee by Colonel Bradstreet. His eyes were sunken and haunted with fear and malnutrition, he was dressed in tattered remnants, he had obviously been badly mistreated and he was on the point of collapse from exhaustion. He asked for Colonel Bradstreet, but it was Lieutenant Colonel John Campbell who saw him.

"My God, man," the new Detroit commander exclaimed, "what happened to you?"

Morris shook his head and waved the question aside, saying instead, "Where is Colonel Bradstreet, sir?"

"Back at Sandusky by now," Campbell replied. He added grimly: "Apparently things were not as he thought they'd be. The Delawares and Shawnees came to Sandusky all right, but evidently they took Ensign Pauli and his detachment prisoner and have gone again."

Morris groaned. "He's been duped! Every step of the way. There is no peace with the Shawnees and Delawares."

Little by little Campbell got the story out of him. After leaving Bradstreet on his mission, Morris continued up the Maumee River until, on August 20, he had come to Pontiac's village. There he found himself immediately treated very badly by the Indians and was in constant danger of his life. He was saved by Jacques Godefroy, who had hidden him in a cornfield all night. Then Pontiac had arrived, and had treated Morris reasonably well. They had conversed in French and Pontiac had boasted of a great alliance growing under him, claiming that he had forty-seven tribes and one hundred and eighty villages at his command, with more joining him daily. Surprisingly, he restrained his men from harming Morris further and allowed him to continue his journey upstream. Perhaps he had known what was awaiting the officer there. Only a few days before Morris arrived at the deserted Fort Miamis, the Miami Indians there under Chief Cold Foot were visited by a band of Shawnees and Delawares who were carrying a war belt toward the Illinois country. The Miamis were asked to kill or turn back any English who came this way.

When Morris had arrived, he was immediately seized, all his goods taken, his clothing stripped from him and then he was bound to a stake to be tortured and burned. Only through the efforts of a young Miami chief named Pacanne, son of the principal chief of the whole tribe, Michikiniqua, had he been spared. A council was held on September 9 and when it was concluded, Captain Morris was given the choice of either returning to Detroit or being killed. The decision had not been difficult for him to make. The next morning he had set out overland for Detroit and it had taken a week of steady, extremely difficult traveling for him to get here to warn Bradstreet, and now he was dismayed to find the colonel was gone

.

Refusing to accept any care for himself until he had gotten word to Brad-street, he sent that officer the journal which he had kept of his travels since leaving the colonel, and enclosed with it a covering letter in which he wrote:

. . .

thus, Sir, have the villains nipped our fairest hopes in the bud. 1 tremble for you at Sandusky; though I was greatly pleased to find you have one of the vessels with you, and the artillery. I wish the chiefs were assembled on board the vessel and she had a hole in her bottom. Treachery should be paid with treachery; and it is more than ordinary pleasure to deceive those who would deceive us .

. .

170

[ October

12,

1764 — Friday ]

"You sail when, Henry?" Thomas Gage asked.

"Within two hours, General," replied Lieutenant Colonel Gladwin.

Gage shook his head. "Lord knows, you deserve it, but I'm damned sorry to see you go, sir. A general whose field officers are incompetent is severely crippled, but when he has officers of the caliber of yourself and Colonel Bouquet, he is well-nigh invincible. You will be sorely missed here."

He shook Gladwin's hand and then handed him a folded piece of paper that was on his desk. "This may interest you. Take it along and read it when you get on board. Good-by, Henry, and good luck."

Gladwin, impressive in his immaculate uniform, snapped to attention and saluted his general. "Good-by to you, too, sir," he said. "And especially good luck. God bless you, sir."

He turned and left, tucking the paper into his pocket as he did so. Returning to his quarters he gathered up his things and boarded the ship. Not until the shore had dropped out of sight in the sea behind them and he had retired to his cabin did he recall the paper Gage had given him and he took it out of his pocket. It was a copy of a letter from Gage to the Secretary of War, which said:

Major Gladwin, having come here from Detroit and his affairs long ago requiring his presence in England, I have given him leave to go home before the 80th Regiment, to which he belongs, is reduced. The services this gentleman has performed will alone be sufficient to recommend him to your protection. I would only presume to hope that his merit will procure him the same rank that every other officer has hitherto obtained who has served in the station of Deputy Adjutant General.

17

1

[ October 17, 1764 — Wednesday ]

From the very beginning of this campaign, Colonel Henry Bouquet had resolved to take no nonsense whatever from the Indians. He had no intention of making any sort of hasty council with them just for the sake of establishing a makeshift peace. If and when a peace would be asked of him by the Indians, as he was sure it would be on this expedition, it would be entirely on his terms and

only

after there was no vestige of doubt left in the minds of any of the chiefs of both Shawnee and Delaware tribes that he could — and, if necessary, would — crush them to oblivion.

The action of Bradstreet at Presque Isle had stripped from him all good humor and the orders which he issued thereafter to his men were neither questioned nor disobeyed. His manner was stern and in every soldier's mind — regular or militia — was implanted the knowledge that, during this campaign, at least, the word of Henry Bouquet was absolute law and the final authority. In short, he was not a man to be trifled with in any respect.

Also, he was through with waiting.

Disregarding the weakness his force had sustained through desertion, and disgusted with waiting any longer for the party of Iroquois which were supposed to have been sent by Sir William to join him, he put his men on the move and did not allow the pace to flag. Between Fort Bedford and Fort Ligonier, and again between Fort Ligonier and Fort Pitt, several of his men were picked off on the flanks and in the rear by tiny parties of Indians, but other than ordering the men to keep alert, he paid little attention to such parries.

On September 15 they passed the site of his bloody battle fourteen months before, and two days later they arrived at Fort Pitt. Here Bouquet found that only the day before his arrival, a large party of Shawnees and Delawares had appeared on the other side of the river and set up camp, then sent a deputation of three men across to the fort, saying they wished to make peace. Suspecting them to be spies rather than peace emissaries, Captain Grant had ordered that they be held as hostages and immediately the camp on the other side of the river was broken up and the remaining Indians fled westward.

Bouquet, pleased at Grant's action, questioned the three captives himself and agreed that they were hardly qualified to act in the name of their tribes. He determined to send one of them back to the tribes with a message and, through the fort's young but able interpreter, Simon Girty, he addressed the Indian.

"Are you Shawnee or Delaware?"

"Shawnee, and you will never conquer my people."

When Girty interpreted, Bouquet stared coldly at the native and said, "Tell him to speak no more, only to listen and listen well. If he speaks

again, I'll have him executed and send one of the others back with the message for his people."

Girty rattled off a string of guttural sentences and the Shawnee lost some of his composure and clamped his lips tightly together. Girty grunted, then grinned at the officer.

"He'll listen now, Colonel."

"Will he be able to repeat what I tell him?"

Girty nodded. "Not only the gen'rul idee of what you say, Colonel, but he'll be able to quote you word for word. They got a knack for that."

"All right, here it is," Bouquet said. He faced the Indian and began speaking strongly and emphatically. "I have received an account from Colonel Bradstreet that your nations had begged for peace, which he consented to grant, on the assurance that you had recalled all your warriors from our frontiers. In consequence of this, I would not have proceeded against your towns if I had not learned that in open violation of these promises, you have since murdered many of our people.

"I was therefore determined to attack you as a people whose word could not be relied on. However, I will one final time put it in your power to save yourselves and your families from total destruction. This can only be done by your giving us satisfaction for the hostilities you have committed against us. First, you are to leave the path open and safe for my messengers from here to Detroit. I am today sending two men with dispatches to Colonel Bradstreet, who commands on the lakes. You will send two of your own people along with them and bring them back safe with an answer. If these two receive any injury, either in coming or going, or if the letters are taken from them, I will immediately put to death the two Indians now in my custody here, and I will show no further mercy for the future to any of the people of the Shawnee or Delaware Nations who may fall into my hands. I allow you ten days to have my letters delivered at the Detroit, and ten days to bring me back an answer."

The strong, unrelenting nature of Bouquet's speech had a profound effect on the Shawnee. Girty whispered to Bouquet that he'd never seen a Shawnee so shaken before. Not commenting, Bouquet ordered the warrior released and then instructed Grant on what to do, since he had no intention of staying here himself for twenty days waiting for the return of his messengers. The word, he knew, would be passed swiftly through the forest. They would know now with what sort of man they had to deal.

Before moving the expedition out, Bouquet, who had finally been able to write a markedly restrained letter to Bradstreet, had the satisfaction of having Gage's letter of chastisement to Bradstreet sent to him first, to read, then seal and relay to the colonel on Lake Erie. In the letter of that packet which was directed to Bouquet by Gage, the condemnation of Bradstreet continued. In fact, Gage had concluded by saying:

. , .

and if they find Colonel Bradstreet is to be thus amused, they will deceive him till it is too late to act and then insult him and begin their horrid murders. There is nothing will prevent this but the fear of chastisement from you, and I think myself happy that you are in a condition to march against them.

But though it was personally satisfying for Bouquet to read such words from his commander, there was little inclination on his part to gloat. He issued final marching orders on September 28 and they were very strict. Under penalty of death, no man was to fire his gun, whether at Indians or for any other reason, except at the colonel's own command. This order was not to be questioned, only obeyed. On October 1, the sheep and cattle were moved across the Allegheny in preparation for the march and the next day the expedition into the wilderness began, Fifteen hundred men crossed the river and began following their commander into a land where never before had an army marched.

On October 6 they camped thirty-two miles from Fort Pitt.

172

Here they encountered their first fresh Indian sign — the tracks of fifteen Indians and the skull of a child impaled on a stake. If it was meant as a warning, it had no effect on Bouquet. He kicked it down and in the morning the march was resumed.

On October 12 they reached a little stream called Sandy Creek,

173

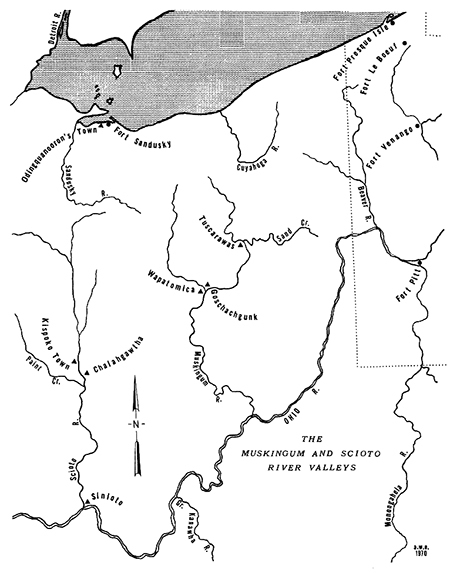

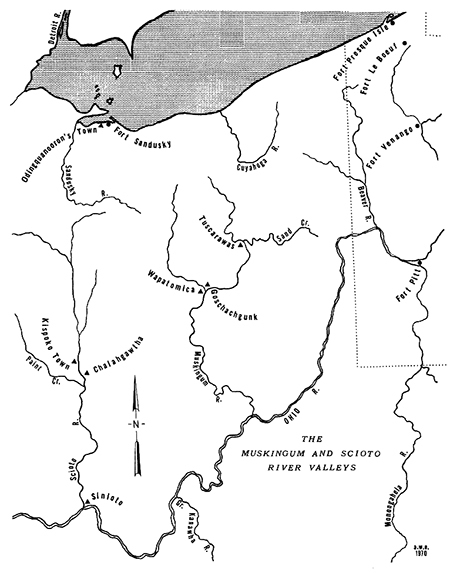

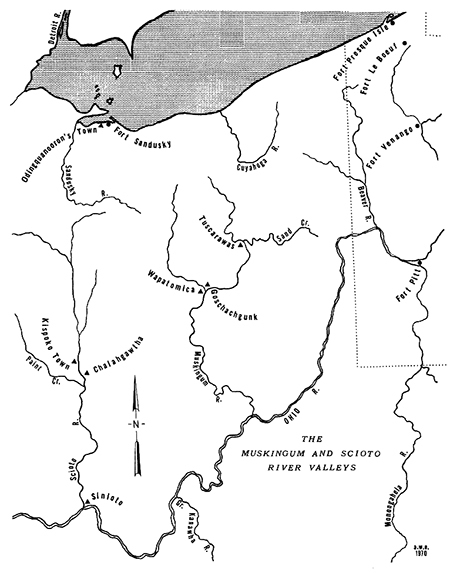

a tributary of the Tuscarawas River, which was itself one of the two principal branches of the Muskingum. Now they began encountering small Delaware villages, but all were deserted. Continuing down Sandy Creek, they camped at a point on the north bank of the little stream, exactly eighty-three miles distant from Fort Pitt.

174

While his men prepared for the night's rest, Bouquet dictated an order. At 7 a.m. the next day, it was read aloud to the troops, who listened attentively:

BY ORDER OF THE COLONEL: This army has already penetrated to the heart of the enemy's country. These perfidious savages have already and severally experienced the valor of Britons, which must have struck them with terror, as they now shun encountering the same gallant troops that formerly put them to flight, and this instance of so distant a progress of his Majesty's successful arms in this part of the vast continent of North

America has hitherto met with no serious opposition. Nor have the barbarians, who brutally destroyed the defenseless inhabitants of the back settlements of our colonies, dared to appear in the face of this small but well composed army in a hostile manner.

The troops will this day proceed to Tuscarawas, a settlement now abandoned but formerly inhabited by a numerous tribe of the enemy Indians.

From the pacific disposition of several savage Nations to the northward, who applied for and have had peace granted to them by Sir William Johnson,

and from appearances lately in this quarter, it is probable that a deputation from the Shawnee and Delaware Nations will sue for peace. Colonel Bouquet desires every person in this army may be acquainted it is his orders that, to avoid unnecessary bloodshed, the troops are generously to forbear treating the savages hostilly till their intentions are fully known. And should they meanly and servily attempt to recover the countenance and favor of any person whatsoever, it is positively forbidden to hold any kind of friendly intercourse with them, by speaking, shaking hands or otherwise. But, on the contrary, to look on them with utmost disdain and with that stern and manly indignation justly felt for their many barbarities to our friends and fellow subjects. They will continue to be regarded as enemies till they submit to the terms that will be offered them and till they have in some measure expiated the horrid crimes they have been guilty of, by a strict compliance with those terms. Ample satisfaction will be demanded and insisted on for all possible reparation of wrongs and such satisfaction as will be adequate to the spirit now exerted by an injured people, and equally consistent with the honor and dignity of the British Empire. Should the savages have the audacity to dispute the access of this army to Tuscarawas, the conduct and bravery of the officers and men will soon retaliate their cruelties on their guilty heads in a manner more becoming their resentments, although repugnant to their humanity.

It was while the reading of the order was going on that the messengers Bouquet had sent off to Detroit caught up to the army. They had not made it. The men related that they had been held by the Delawares and not permitted to go to Lake Erie. They had not, however, been in any way mistreated, nor had their letters been taken from them. They had been asked to tell Bouquet that within a few days the principal chiefs would arrive to hold council with him.

Having no intention of waiting on their favor, Bouquet again put his army on the march and followed the main Indian trail to the site of Tuscarawas.

175

Here the branch they were following emptied into the much larger Tuscarawas River many miles upstream from where the Tuscarawas and Walhonding Rivers joined to form the Muskingum River. Here there was a fording place and here a number of Indian trails branched off, leading to Detroit, Cuyahoga and the Shawnee towns on the Scioto. Bouquet ordered camp made and a strong palisade erected to protect stores and baggage.

In the morning the march began again downstream on the river. And finally there was Indian contact.

A deputation of Delaware, Shawnee and Seneca chiefs appeared in the twilight, unarmed, and came directly to Bouquet, paced by a guard of soldiers. Without preamble they told Bouquet that their warriors were massed in great numbers just eight miles away. They asked Bouquet to name the

time and place for a council and Bouquet agreed. After a short discussion the chiefs turned and left in the direction from which they had appeared. As soon as they were gone, Bouquet set his men to constructing a sort of arbor beneath which the council could be held.

176

And now it was the morning of October 17 and the time for the first council had arrived. Bouquet, knowing the Indians would be impressed by the greatest possible show of strength, suitably situated his troops; and the sight of fifteen hundred men bristling with weapons, their fixed bayonets glittering in the morning sun, was indeed an impressive sight. Here were the Royal Americans in uniforms that were a splash of scarlet across the meadow, and there were the tartans of the Highlander regulars. Here were the moccasined and leather-shirted frontiersmen, and there the quaintly garbed provincials. Abruptly there was a brief roll of the drums and an expectant hush fell over the assemblage as a group of seventy or eighty Indians approached, being led by the principal chiefs of the three tribes gathered here — Custaloga, chief of the Delawares, and better known to the English as White Eyes, beside whom walked Turtle's Heart,

177

chief orator of that tribe, in whose hand was a bulging leather pouch containing wampum belts; Hokolesqua, principal chief of the Shawnees, well known as Chief Cornstalk, beside whom strode his war chief, Pucksinwah; and Kyashuta, chief of the band of Senecas who had broken from the rest of their tribe when it had agreed to meet Johnson's demand and attend the Niagara Congress.

With amazing calmness and dignity, looking neither to left nor right at the ranked soldiers who stared murderously at them, they walked to the huge arbor that had been constructed, where Bouquet and his officers sat waiting and, behind them, several secretaries poised to take down on paper all that was spoken.

At a motion from Custaloga the greatest part of the following warriors stopped and sat on the ground. This was about a dozen yards from the arbor. The chiefs, however, along with half a dozen others, did not stop and sit until they were well under the arbor.

No words were spoken by anyone as the calumets were packed with

kinnikinnick

and the ceremony of smoking began. In turn, from each of the chiefs, Bouquet and the officers accepted and puffed a time or two on the pipes and handed them back. At last, when all smoking was finished and the calumets laid aside, it was Kitehi who rose and began to speak, offering wampum belts at the appropriate pauses.

"Brother," he began, "I speak in behalf of the three nations whose chiefs are here present. With this belt I open your ears and your hearts, that you may listen to my words.

"Brother, this war was neither your fault nor ours. It was the work of the nations who live to the westward, and of our wild young

men who would have turned and killed us if we had resisted them. We now put away all evil from our hearts and we hope that your mind and ours will once more be united together for the common good.

"Brother, it is the will of the Great Spirit that there should be peace between us. We, on our side, now take fast hold of the chain of friendship; but, as we cannot hold it alone, we desire that you will take hold also, and we must look up to the Great Spirit, that he may make us strong and not permit this chain to fall from our hands.

"Brother, these words come from our hearts and not only from our lips. You desire that we should deliver up your flesh and blood who are now captive among us; and to show you that we are sincere, we now return to you as many of them as we have at present been able to bring."

He made a circular motion with his hand above his head and immediately the horde of warriors gathered in the distance opened and a party detached itself and walked forward. Within five minutes, eighteen English prisoners had been turned over to Bouquet's officers.

Kitehi nodded when this was finished and added, "You shall receive the rest as soon as we have time to collect them."

Having completed the principal address, Kitehi now took his place with the others. One by one then, chief after chief of tribe and village arose and came forward to speak, each of them saying in one way or another virtually what Kitehi had said, and each of them, before returning to his place, presenting Bouquet with a bundle of smooth cedar sticks bound together with rawhide. Each of these sticks represented one prisoner and each bundle was the number of prisoners the individual chief pledged himself to give up.

Since it was not proper, in the procedures of formal council, for Bouquet to give his reply on the same day, the council now broke up, to be resumed tomorrow morning. As the officers moved away, Chaplain John Thomas of the 6oth Regiment moved up beside Colonel Bouquet.

"It looks," he murmured to the commander, "as if they're serious about ending the war and giving up their prisoners, doesn't it?"

"Nowhere near serious enough," Bouquet replied shortly. "They'll be surprised at what I have to say to them tomorrow, I'll wager."

[ November 6, 1764 — Tuesday ]

Colonel John Bradstreet looked with mild disgust at the wet and shivering men crouched naked around the fires here at the mouth of the river, trying to get their clothing dry before the journey resumed. The delay irked him but he supposed he had to at least give them this respite anyway. He ignored entirely the murderous looks which were being directed his way. What the rank and file thought of him bothered him not at all. In fact, he didn't even care what his subordinate officers thought of him. He was lost

in new thoughts of what glory would come to him when his great plan for the elimination of all the Indians was made public.

He'd been working on this plan ever since leaving Sandusky to head east and now, even though most of his notes had become wet and many of them were illegible, still he had the plan fixed well enough in his own mind that he could quickly write it out again. As a matter of fact, this might be the ideal time to do it, while these idiot soldiers of his continued to wring themselves out around the fires.

He strode to the tent and got out fresh, dry writing materials and then carefully separated the soggy sheets. The words written on them had little to do with the campaign behind him. In the manner of most megalomaniacs, since it was a distasteful episode pointing to his own ineptitude, he simply refused to think about it. The glory lay ahead, not in what was behind.

It was just as well that he didn't dwell on those events that had occurred since leaving Detroit. To dwell on them would have been to admit his own incompetence, and this was something he would not,

could not,

do. Having left Detroit upon hearing that the English detachment at Sandusky had been taken prisoner, Bradstreet led his army back to Sandusky Bay. It was immediately apparent that the area was deserted. Absolutely refusing to believe that the Indians could have hoodwinked him and had no intention of coming back, Bradstreet waited. At last, after three or four days, a little group of warriors hesitantly approached, though with no chiefs among them. They said they were emissaries from their tribe and that if the colonel would keep waiting and refrain from attacking their villages, they would begin bringing their prisoners in by the next week.

It was vindication for Bradstreet and his face became wreathed with a great smile as he agreed — against the advice of practically every other officer in his army. They waited . . . and waited. The colonel was still positive that there must be some mistake in the report of Ensign Pauli's detachment having been taken captive and reasoned that they had probably returned to Detroit by now and the whole thing was no more than a rumor.

But then had come the double blow that had sent him mentally reeling. Letters from both General Gage and Colonel Bouquet came — letters which severely raked him over the coals, made him out to be a fool and reprimanded him in a way he had never in his whole military career been reprimanded before. The harsh words of Gage in particular almost made him physically ill. And not content in reprimanding him, Gage now had given him an order to immediately lead his army south through the Ohio wilderness to launch an attack against the Shawnees living along the Scioto River.

Even while he staggered under the enormity of all this, the second blow

had come. A messenger arrived from Detroit, bearing with him the journal of Captain Morris's abortive trip up the Maumee River, along with that officer's accompanying letter — undeniable proof that he, Bradstreet, had been duped by the Indians; that he, a skilled military commander had been outthought, outmaneuvered, entirely outwitted and made a complete

ass

of by a pack of ignorant savages!

His wrath made him inchoate and only after a long while did some degree of normalcy return to him. His officers, who had stood back, now came to him, wondering aloud if they should get their men ready for the move southward into the enemy territory. All he did was rebuke them severely for bothering him. Day after day they continued to perch at Sandusky and, to the consternation and incredulity of his officers and men, it became clear that he was still determined to wait here for the Indians to honor their promises to him! His temper became such that it was a decided risk for anyone even to address him. His actions were at best capricious and the harshness with which he treated his troops increased and, with it, the discontent of the whole army. Most inexplicable to them was his continued tenderness of thought toward the Indians of these woods while at the same time never missing any opportunity to curse his own Iroquois allies, which enraged them no little.

Finally, on October 14, he dispatched one of the French volunteers with him, Louis Hertel, along with a small party of his discontent Indians, to Colonel Bouquet with a message; a message which declared that because of the advanced season, he was no

longer able to remain in the Indian country and would soon be returning east.

Two days later, after having sent out a party of five Iroquois to hunt for some venison, which he had a taste for, and two of his New Jersey privates to catch some fish for his table, he abruptly decided that he had had enough of this country. He charged out of his tent bellowing orders for the men to load the boats and the army to be ready to embark for Niagara within the hour. The camp became a beehive of activity as gear was gathered and the loading of the batteaux began. Then several concerned officers came to him in a little group and one of them self-consciously cleared his throat.

"Sir," he said, "what about the men who are out? The Indians you sent out deer hunting? And the Jersey men?"

"What about them?" Bradstreet growled.

"They're not back yet, sir."

"Then that's their problem. We'll go without them."

The officers were shocked. "But Colonel," their speaker protested, "those men were sent out on your orders. Can't we at least leave one of the batteaux here for an hour or two for them? It could catch up to us easily enough.

"

"No!" Bradstreet roared. "They can stay here and be damned! Not one boat will stay here to wait one minute for them. We're ready to leave now and so, by damn, we're leaving!"

And so they did.

Several of the more high-ranking officers hesitantly asked the colonel why they were going east, when the general's orders specifically had been for them to move south and attack the Shawnees to support Bouquet. At first Bradstreet refused to discuss it, but at last he mumbled such excuses as the season growing too late, provisions failing, the way there being too difficult a passage, and no good maps to guide them. When the officers declared that they were willing to try anyway, he silenced them and would not discuss it further.

On October 21 they had reached the vicinity of the mouth of the Cuyahoga River.

178

Great black clouds were piling up over the lake and it looked as if a good storm was in prospect. Although a thousand boats could have found relatively safe harbor just a short way upriver and weathered nearly any storm, Bradstreet ignored all suggestions in this respect and ordered camp to be made on an exposed beach. Within mere hours one of those fierce Lake Erie tempests was full upon them. Great waves formed and rolled ashore and the beached boats were beaten and capsized and smashed to pieces. For three days the storm raged on and when at last it was over and they took stock of the damage, it was found that most of the ammunition, provisions, arms, baggage and six cannon were lost and the remaining boats, all of them in very bad shape, were no longer enough to carry everyone.

Bradstreet solved this problem by ordering all his Indians and one hundred and fifty of his provincials to make their way to Niagara as best they could on shore. With that, he set out with his remaining force in the boats that were left. And on November 4, seventeen days after having left Sandusky, they arrived at Niagara.

179

By this time, having for many days already been working on his grand plan for the extermination of the Indians, Bradstreet was in no mood to rest, though his men needed it badly. What he wanted to do was get back east so he could expand and promote his ideas. He discharged the few Indians with him in a few curt words, the next morning had his men get aboard the remaining batteaux and a couple of schooners from the fort and set off for New York via Oswego, the Mohawk River, and Albany.

This afternoon they had reached Oswego but, as luck would have it, another storm caught them before they landed. One of the schooners loaded with troops foundered and a number of men were drowned. It was only with the greatest of exertion that the others were saved.

And so now, while his troops wrung themselves dry before roaring fires and muttered imprecations against a commander whom many of them

could have joyfully slain without qualm or conscience, Colonel John Bradstreet busied himself with dashing off on fresh paper his ideas on annihilating the Indians. The strange thing was, however, that the Indians he inveighed most against were the staunch allies of the English, the Iroquois, while those for whom he recommended the most tender treatment were the Indians of the upper Great Lakes. He knew he'd still have a bit of revising to do on it, but now he read over the first brief outline he had made:

Of all the savages upon the continent, the most knowing, the most intriguing, the less useful and the greatest villains are those most conversant with the Europeans and deserve attention of the government most by way of correction, and these are the Six Nations, the Shawnees and Delawares. They are all well acquainted with the defenseless state of the inhabitants who live on the frontiers and think they will ever have it in their power to distress and plunder them. And they never cease raising the jealousy of the Upper Nations against us, by propagating amongst them stories such as to make them believe the English have nothing so much at heart as the extirpation of all savages. The apparent design of the Six Nations is to keep us at war with all savages but themselves, that they may be employed as mediators between us and them

—

at continuation of the expense to the public, which is too often and too heavily felt, and the sweets of which these Six Nations will never forget nor lose sight of if they can possibly avoid it. That of the Shawnees and Delawares is to live on killing, captivating and plundering the people inhabiting the frontiers, long experience having shown them that they grow richer and live better thereby than by hunting wild beasts.

This campaign has fully opened the eyes of the Upper Nations of Indians. They are now sensible that they are made use of as dupes and tools of those detestable and diabolical Six Nations, Shawnees and Delawares, and it would require but little address and expense (the posts and trade properly fixed) to engage the Upper Nations to cut them from the face of the earth (and they deserve it) or to keep the Six Nations in such subjection as would put an end to our being any longer a kind of tributary to them. And their real interests call upon the Upper Nations to destroy or drive out the Shawnees and Delawares out of the country they now possess, to hunt in. This they know and would soon put either into execution if assured his Majesty would not suffer any other savages to live there. Happy it will be when savages can be punished by savages, the good effects of which the French can tell. That we can punish them is beyond doubt, whenever wisdom, secrecy, dispatch and good troops in numbers proportionate to the service are employed

.

He intended to write more — much more — but this would do for a start, and John Bradstreet was pleased with it. Already he could see himself being hailed as the master planner, the brilliant strategist who, with stroke of pen, wiped out the great deterrent to expansion and scourge of the English, which had for so many years plagued them.

Yes, indeed, laurels were ahead for Colonel John Bradstreet.

180

[ November 28, 1764 — Wednesday ]

Colonel Henry Bouquet was back!

Fort Pitt virtually split its seams with excitement as the weary army led by Bouquet hove into view on the west side of the Allegheny, moved to the river's edge and began the crossing. The riverbank of the fort side became mobbed with cheering people — soldiers, settlers, frontiersmen, shopkeepers, traders, people of every description and state — and the air was filled with the din of their voices. Soldiers lined the ramparts shoulder to shoulder, raising their rifles time after time to fire into the sky, while for more than an hour the heavy artillery rumbled and roared and belched great bursts of fire and smoke.

Bouquet was back and the Indian War was ended and there was peace!

Never in its turbulent history had Fort Pitt been so wild with excitement. Never had the huts and cabins and houses of adjacent Pittsburgh seen so much laughter and backslapping and delight. Never had so many happy reunions been effected. And the story of how it had all come about was on everyone's lips.

After the initial council session Bouquet had held with the Indians there had been a delay. The council scheduled for the next day had been postponed because of a driving rainstorm which had come up at dawn and lasted most of the day; but on October 19 the council had resumed. Colonel Henry Bouquet had not been wrong in his comment that the Indians might be surprised at what he had to say. Obviously they had expected him to be all smiles and generosity and eager to settle things quickly and be off. Such was not at all the case.

With such interpreters as Simon Girty, his brothers James and George, Matthew Elliott and Alexander McKce reiterating in the Delaware, Seneca and Shawnee Indian tongues every phrase as he finished uttering it, Bouquet had launched into them with a tongue-lashing such as none of them had ever before received. Even in his opening statement it was obvious that this was going to be a tough speech, for he began to talk without any of the usual courteous addresses such as "My children," or "Brothers," or the like. He simply stood before them and when every ear was attuned to what he would say, he began:

"Sachems, war chiefs and warriors. The excuses you have offered are

weak and have no weight with me. Your conduct has been beyond defense or apology. You could not have acted, as you pretend you have done, because of fear of the western nations, for had you stood faithful to us, you knew that we would have protected you against their anger. And as for your own young men threatening you, this I cannot accept, for it was your duty to punish them if they went amiss."

Already the eyes of his listeners were widening as the interpreters caught up to him in this first lengthy pause, and many of the Indians looked startled. It was not at all what they had expected to hear. As soon as the interpreters stopped, Bouquet went on in a loud voice.

"You have drawn down our just resentment by your violence and perfidy. Last summer, in cold blood and in a time of profound peace, you robbed and murdered the traders who had come among you at your own express desire that they do so. You attacked Fort Pitt, which was built at the forks of the Ohio not only with your consent, but at your request. You have destroyed our outposts and garrisons wherever treachery could place them in your power."

Again he paused to let the interpreters catch up, and then flung a hand out to point at the ranks of soldiers standing on both sides. "You assailed our troops — the same who now stand before you — in the woods at Bushy Run, and when we had routed you and driven you off, you sent your scalping parties to the frontier and murdered many hundreds more of our people.

"Last July," he continued after another pause, "when the other nations came to treat for peace at Niagara, you not only refused to attend, but you sent an insolent message instead, in which you expressed a pretended contempt for the English, calling them old women. At the same time you told the surrounding nations that you would never lay down the hatchet.

"Afterwards, when Colonel Bradstreet came up Lake Erie with his army, you sent him a deputation of your men and concluded a treaty of peace with him, but your engagements were no sooner made than broken. And from that day to this, you have scalped and butchered us without ceasing!"

Bouquet stopped and looked sharply at each of the principal chiefs and then at the horde of at least a thousand warriors standing silently several hundred yards beyond the ranked soldiers. The colonel shook his head. "Nay," he said, "I am informed that when you heard this army was penetrating the woods, you mustered your warriors to attack us and the only reason you did not do so was because you discovered how greatly we outnumbered you with the men of this army and that to the north under Colonel Bradstreet, which could join with us swiftly to destroy you all.

"This," he added, "is not the only instance of your bad faith, for since the beginning of the last war you have made repeated treaties with us and

promised to give up your prisoners, but you have never kept these engagements, nor any others."

Bouquet slammed his fist into his palm with a loud smack and cried out, "We shall endure this no longer! I am now come among you to force you to make atonement for the injuries you have done us. I have brought with me the relatives of those you have murdered, and they are eager for vengeance! Nothing restrains them from taking it but my assurance that this army shall not leave your country until you have given ample satisfaction.

"Your allies, the Ottawas, Chippewas and Hurons have begged for peace; the Six Nations have leagued themselves with us; the Great Lakes and the rivers around you are all in our possession; your friends, the French, are in subjection to us and can do nothing more to aid you. You are all in our power and, if we choose, we can exterminate you from the earth!"

He let the interpreters catch up and when he continued, his outrage had abated some and his voice had become gentler, though by no means friendly. "Yes, you are in our power, but the English are a merciful and generous people. We are averse to shedding blood, even that of our greatest enemies. If it were possible that you could convince us that you sincerely repent your past perfidy, and that we could depend on your good behavior for the future, you might yet hope for mercy and peace. Therefore, if I find that you faithfully execute the conditions which I shall prescribe, I will not treat you with the severity you deserve.

"I give you twelve days from today to deliver into my hands all the English prisoners in your possession,

without exception!

All of them — men, women, children, whether or not you have adopted them into your tribes, whether or not they have married among your people, whether or not they have sired or borne children with you or among you, whether or not they wish to stay among you —

all of them

who are living among you under any denomination or pretense whatsoever!

"Further, you are to furnish these prisoners with clothing, with provisions, and with horses to carry them to Fort Pitt. When you have fully and faithfully complied with these conditions, then and only then will you know on what terms you may obtain the peace you sue for."

If ever a group of men had been whipped by words and awed by threats, it was this body of Shawnees, Delawares and Senecas now before Bouquet. Never had any white commander dared to bring his army so far into their territory; never had any white man ever before spoken so harshly to them; never had any other commander refused to bargain until such far-reaching conditions were met. They were chagrined and they were more than a little frightened.

On the next day their replies had been lifeless, even insipid, with none of the flamboyance of oratory which so often before had issued from them.

And though they approached the matter in a roundabout way, attempting in every way possible to preserve face and dignity, their reply boiled down to this: they would return to their different villages at once and return with their prisoners — all of them — in the prescribed manner and in the prescribed time.

Lest they think he had been too easily mollified, Bouquet gave them one final word. "I will not wait here," he told them, "but you will know where I am. I will move my army into the very center of your nation, beginning at once, so that if your promises are not met, mine will be more swiftly fulfilled! And that you will make no attempt at deception, I will keep with me as hostage your principal chiefs who spoke here, who will be well treated and returned to your people safely — but not until every prisoner has been surrendered."

A coincidence occurred then, but it had the appearance of a plan to emphasize his strength and ability to carry out his threats. Under Captain William McClellan, a tardy corps of Maryland volunteers which had arrived late at Fort Pitt, had found Bouquet gone and had followed his path, chose this moment to arrive. The same thought was instantly in every Indian mind: how many other smaller forces like this were still coming? Enough were already here to cripple them, perhaps enough to annihilate them. Looking fearfully over their shoulders, the Indians departed at once.

As he promised, Bouquet moved his army downstream at once, down to near the head of the Muskingum River. This was not only the heart of the Delaware nation, it was equally the traditional meeting place of both the Shawnees and Delawares for their intertribal councils. It was a beautiful site, where the Walhonding River flowing in from the west and north joined the Tuscarawas River flowing in from the east and north. Their merging formed the great Muskingum River which flowed south and east, eventually to empty into the Ohio River.

On the east side of the Muskingum here was the sprawling Delaware principal town of Goschachgunk, and on the west side of the river directly across from Goschachgunk

181

was the somewhat smaller Shawnee town of Wapatomica. Bouquet knew that from this point, should it become necessary for the army to march against them, it was only a matter of about ninety miles southwest to the principal Shawnee villages on the Scioto River.

182

Even though he was holding the principal chiefs as hostage, Bouquet took no chances on a sudden massive surprise attack against him. He ordered the immediate erection of a substantial fortification, as well as makeshift barracks for the prisoners to be released and the construction of another council arbor. Awed as much by their commander as the Indians had been, the soldiers worked hard and they worked fast. Hundreds of trees were felled and very quickly a surprisingly good defensive works was

erected, along with the rude but functional structures to be used as hospitals, storehouses, cabins and dormitories for liberated prisoners, plus the necessary council arbor. A score or more of sturdy married women, mainly wives of frontiersmen and border settlers brought along for just this purpose, prepared themselves to take charge of any women and children prisoners to be delivered up.

And the prisoners came.

In singles or small groups, by the tens or by the scores, they were led to this place by the returning Indian parties and turned over to Bouquet's army. Day by day these parties came, meekly and submissively handing over all their prisoners, including even those who had no desire to return, who wept and screamed and fought against such liberation — those who had become adopted into the tribes, had become part of them, had been brought up through childhood in them, had married in them, had children in them. There were as many tears of anguish shed as there were tears of joyful

reunion. In some cases the released prisoners had to be physically restrained from running away to rejoin their adopted people.

During the midst of this activity the Frenchman carrying the message from Colonel Bradstreet, Louis Hertel, arrived. The dispatch he carried informed Bouquet that the northern campaign was being given up and that Bradstreet was going home. Hertel confirmed that no prisoners had been given up to him by the Wyandots or the Shawnees or the Delawares and, in fact, Ensign Christopher Pauli and his small detachment, sent to rebuild Fort Sandusky, had been taken captive. The colonel's shoulders slumped at the news.

Now, in addition to his own difficult job here, Bouquet had to send a detachment to the Wyandot country near Sandusky Bay — along with an escort of Shawnees and Delawares willingly given by his hostage principal chiefs who guaranteed success of the mission — to demand the return of Pauli and his men, along with the other prisoners which Bradstreet should have liberated.

Nor was the fact lost on Bouquet that once again Bradstreet had, by failing to follow his orders, narrowly missed placing Bouquet's force in jeopardy. Had this message from Bradstreet come only a few days before this and fallen into Indian hands here, it could have greatly encouraged the red men to consider Bouquet not quite so strong as he let on, perhaps resulting in attack rather than in full submission and deliverance of prisoners. But, thankfully, the time for that was past. He had cowed them — using the threat of Bradstreet's force as an extra club — as they had never before been cowed, and the liberation of prisoners continued.

Throughout it all, Bouquet maintained his stern attitude, permitting no fraternizing with the Indians by his men and reminding the tribes that until conditions were fully met, he must continue to treat

them as enemies. He knew only too well that any softening on his part, and show of leniency or friendliness by him or his men, might yet be interpreted as weakness or indecision or timidity. The cardinal rule was clear in his mind: only when he had proved to them clearly and beyond any doubt that he could subdue them at any time by force, only then could he indulge the luxury of treating them with the kindness and natural clemency toward which he was naturally inclined.

By early November so many prisoners had been returned that it was becoming difficult to care for them and so, on November 9, Bouquet had given orders for a detachment under Captain Abraham Buford

183

to lead this first contingent of one hundred and ten liberated prisoners back to Fort Pitt.

Still more prisoners were brought in — including Ensign Pauli and his men and the captives of the Wyandots — and day after day their numbers mounted and the scenes of misery or joy that accompanied them were wrenching to every heart there, Indian or English. And when at last the conditions had been met and the council reconvened, Colonel Henry Bouquet released the hostages he had been holding and the speeches began anew.

"Brother," said Kitehi, extending a broad belt of white wampum, "with this belt I dispel the black cloud that has so long hung over our heads, in order that the sunshine of peace may once more descend to warm and gladden us. I wipe the tears from your eyes and condole with you on the loss of your brothers who have perished in this war. I gather their bones together and cover them deep in the earth, that the sight of them may no longer bring sorrow to your heart, and I scatter leaves over the spot so that it may depart forever from your memory,"

When Simon Girty had interpreted the guttural intonations to English, Kitehi continued:

"The path of peace which once ran between your dwellings and ours has lately become choked with weeds and thorns, so that no one could pass that way. So long has it been overgrown that both of us have almost forgotten that such a path had ever been. I now clear away all such obstructions and make a broad, smooth road so that you and I may freely visit each other, as our fathers used to do. I light a great council fire, whose smoke shall rise to the skies in view of all nations, while you and I sit together in friendship again and smoke the calumet of peace before the blaze."

Kitehi's speech was only the first of many along the same line and a multitude of belts were given, along with speeches of peace. For one of the few times in a long career of dealing with Indians, Bouquet felt the wonderful conviction within him that they spoke with absolute sincerity. It took several days for all the chiefs to speak but then, at last, it was Bouquet's turn. He replied

:

"My children, by your compliance with the conditions which I imposed upon you, I have been satisfied completely of your sincerity in wishing peace between us, and I now receive you once more as brothers. The English King, however, has commissioned me not to make treaties for him, but rather to fight for him. Although now I offer you peace, it is not in my power to settle the precise terms and conditions of it, by which both of us must be bound. For this I refer you to Sir William Johnson, who you know is His Majesty's agent and Superintendent for Indian Affairs. It is he who will settle with you the articles of peace and determine everything in relation to opening trade among you again. Two things yet, however, I must insist on. First, you are to give hostages freely, as security that you will keep faith and will send, at once, authorized deputations of your chiefs to Sir William Johnson. Second, these chiefs must be fully empowered to act for you and speak for you, to treat for peace in behalf of your entire nations, in a manner which will be binding upon all of you. Finally, you must, without the slightest deviation, bind yourself to adhere completely to everything that these chiefs shall agree upon in your behalf."

Such a demand was not unexpected and it was agreed to with alacrity. Even before Bouquet himself left the area, the delegation of chiefs with two hundred or more unpainted warriors in tow was on its way for the treaty talks with Johnson at Fort Stanwix on the upper Mohawk River. And as Bouquet prepared to give his own army the command to return to Fort Pitt, he was visited by Hokolesqua — Cornstalk — principal chief of the Shawnee tribe.

"When you came among us," Hokolesqua said, "you came with hatchet raised to strike us. We now take it from your hand and throw it to the Great Spirit, that he may do with it what shall seem good in his sight. We hope that you, who are brave warriors, will take hold of the chain of friendship which we now extend to you. We, who are also brave warriors, will take hold as you do and, in pity for our women and our children and our old people, we will think no more of war."

And so now it was all over and today, with his weary but exultant army behind him, with two hundred more liberated prisoners among them, Colonel Henry Bouquet rccrossed the Allegheny and was once again at Fort Pitt.

[ December 13, 1764 — Thursday ]

For many years past, nothing had given Major General Thomas Gage so much pleasure as writing the letter he was just now finishing to Lord Halifax. Step by step he had gone over the brilliance of the campaign just concluded by Bouquet, from the gathering of the troops and their departure from Fort Pitt to his dealings with the tribes that had caused so much woe, the subsequent submission of the Indians and liberation of their prisoners

and the ultimate, victorious return to Fort Pitt again, where the army had been disbanded.

Now, in conclusion, he dipped his pen again and wrote the words which brought him such utmost satisfaction:

I must flatter myself that the country is restored to its former tranquility and that a general and, it is hoped, lasting peace is concluded with all the Indian Nations who have taken up arms against his Majesty.

I remain,

etc.

Thomas Gage