I had a camera once. When I found it wasn’t working, I had a sigh of relief.

Simon

The name ‘Norton’ is a fake. Simon’s paternal grandparents, from Germany, died before he was born – ‘No Nazis involved.’ His paternal grandfather anglicised the name from Neuhofer – i.e. New Towner, usually turned into Newton – then fiddled the result to sound less desperate. The only thing we can say for certain about these people, Simon pronounces sententiously, ‘is that when the surname was being used in Germany, the one place the Neuhofers did not live was in any village called Neuhof’. Then he sits back and stares at me happily, waiting for understanding to dawn.

The fact is, for all the interest Simon takes in his ancestors, you’d think he was bred in a flowerpot.

The rest of that day’s gentle journey through the South-East of England was taken up with Simon tracing our route on the Ordnance Survey map with his forefinger. He is extraordinarily bad at this. Invariably, he knows where we were ten minutes ago, or where we are about to be after the next level crossing; it’s where we are now that boggles him. He’s in a constant fret to find the spot. Every fifteen or twenty minutes he’ll succeed, look up, catch my attention and desperately point through the window at a ‘site of special historical interest’ several seconds after it’s disappeared from view. Simon’s general attitude to the third dimension is wary and defiant. It is always playing tricks on him. Two and 196,883 dimensions are the ones Simon prefers. He can spend the afternoon in his bath with twenty-four dimensions and suffer no ill effects at all. But every time he looked up from his map to point out a racecourse or a well-known housing estate that had once appeared in the New Scientist because it was built in the shape of a snowflake, a tall bush had got in the way, or the train was making an unexpected detour around a hill, or everything was pitch black because we were in a tunnel.

Between these annoyances, Simon devised games. ‘What is the minimum number of London Underground stations you have to go through to get all the letters of the alphabet?’

This is an old one of his.

‘Now, let me see, H ,’ I suggested, taking out my notebook and using appropriate Simon noises to help me along. ‘You take the Circle Line west from King’s Cross, which gets you, A

,’ I suggested, taking out my notebook and using appropriate Simon noises to help me along. ‘You take the Circle Line west from King’s Cross, which gets you, A  , let’s see now, Baker Street, that’s a, b, c, e, g, i, k, n, o, r, s, t. Then take the Bakerloo Line to …’

, let’s see now, Baker Street, that’s a, b, c, e, g, i, k, n, o, r, s, t. Then take the Bakerloo Line to …’

Simon doesn’t use his fingers or paper when he’s playing this type of memory trick. With exactly the same expression on his face that he has when analysing calculations, he parades stations through his recollection, snipping off letters. When my attempt crashed into the buffers after the third station, he began again at King’s Cross: ‘Northern Line to … then change at … next the Jubilee Line to … U (yawning) … St John’s Wood – fourteen stops in all.’

(yawning) … St John’s Wood – fourteen stops in all.’

The point about dimensions holds here, too. The Tube is one of the few places Simon never gets disorientated, because under London there are no landmarks to miss. Down there, the third dimension is made up entirely of shiny coloured tiles and adverts for Jack Daniel’s.

Another game was ‘What’s the smallest portion of the map that’s got every letter of the alphabet in it? It was a visit to Cornwall that made me think of this one,’ he said with pride. ‘There are lots of places with a “z” in them down there. Ohhh, look, there! THERE!’ Simon began stabbing at the window of our carriage. Flashed past on the other side: a break in the hedgerow. Beyond it, macadam, the glint of metal, a slash of something red and fat. Then it was gone. Simon beamed with satisfaction. ‘Weybridge Station – there used to be a Bridge Club there,’ he pronounced.

It’s Simon’s belief that all children should have compulsory lessons in orienteering and how to use public transport, ‘so they can learn to enjoy the countryside before they reach driving age, and as a result never want to learn to drive’.

The idea of representing something in different formats is a fundamental one in mathematics, so this education in map-reading and bus timetables would not just stop children from getting lost and being a worry to their parents, it would help them with their algebra homework.

The only other ancestral snippet I extracted was that every week of the year, on Friday, and also at Christmas, Simon’s father drove the family down to Woking in the Bentley to visit Kitty Hobbler. It is the one point about those days that remains distinct in Simon’s mind – not because of the droning regularity of the trips, but because, strapped in the back seat in a swirl of petrol fumes and his mother’s ‘particularly pungent’ French cigarettes, ‘that’s when my dislike of cars began’. Cars are ‘smelly, they kill children, they destroy the planet’.

‘So do buses. Why pick on cars?’

‘Cars are worse. Cars corrode mankind. Incidentally, have I told you my method of remembering the names of the Lanthanides?’ The Lanthanides are soft metals that burn in air, and appear as a row of chemical elements dangling off the bottom of the periodic table.

‘Loathsome Cars Produce Noxious Polluting Smelly Exhaust Gases: They Destroy Human Environments, Take Young Lives.’

And for the Actinides, another dangling row of metallic elements, this time radioactive:

‘Avoid These Perils. Use No Private Automobiles. Cars Bring Complete Enslavement For Mankind, Not Liberation!’

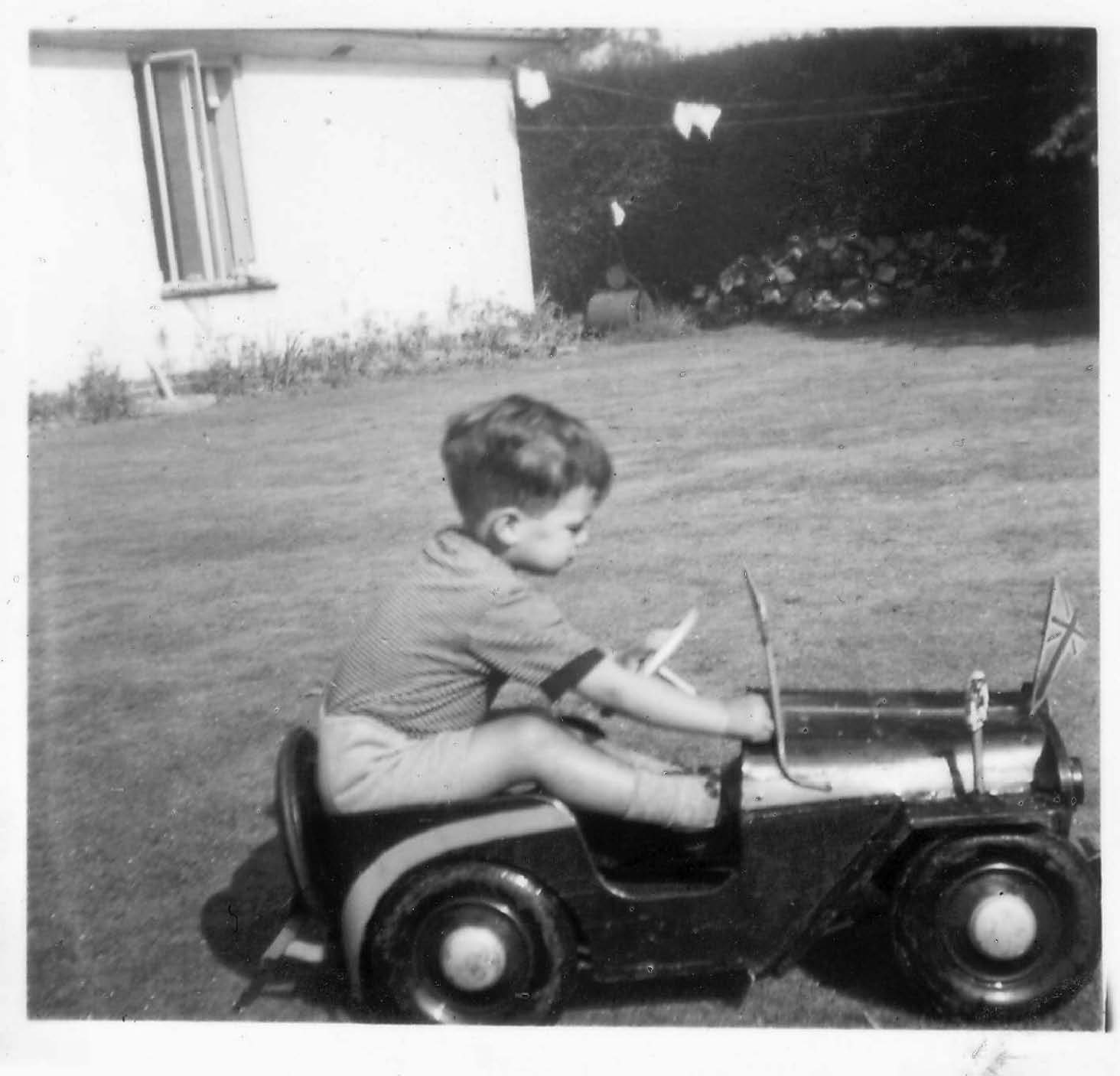

Simon, aged two.

‘Now, about your grandparents …’ I began, determined to return to biography.

‘Have you seen this?’ Simon burst out.

He dragged out a Philips atlas: ring-bound, super-size. The two most important books in Simon’s life are both atlases: the Atlas of Finite Groups, which made him famous throughout the world of Group Theory, and this grubby guide to the roads of Britain. Opening the cover, he flicked past a couple of pages. The paper, through his fingering, has acquired a dirty down.

If his house were burning down, this Phillips road atlas, says Simon, is the only thing he would run through the falling timber to retrieve.

Each time Simon travels along a new route on a bus, he traces over the relevant line in this book with a pencil. The Midlands, Kent and the Lake District are coated in smudge. Scotland, with the exception of a few contrails of graphite around Edinburgh and Scrabster, is largely crisp and clear. Along inland borders, his squiggles tend to get lost because on Phillips’ maps the county divisions are grey. The pages around Cambridge, submerged in carbon, have torn loose and flop about the middle of the book.

Simon is in the process of transferring the shading from one Phillips atlas to a new one. It isn’t easy to discover why this record of the-macadam-I-have-known he’s covered matters so much to him.

‘Is it a sort of stamp album? Are you hoping to collect all the roads of Britain in it?’

‘No.’

‘A record of every bus journey you’ve ever made?’

‘No.’

‘Would you like it to be like that? Would that be the ultimate? Is it your memory? Are you being peculiar and trying to write out a sentence in bus journeys across the surface of the country?’

‘No!’

One of the things I enjoy about Simon is his revulsion at my attempts to make him novelistically tidy.

Some of the pencil lines in his road atlas shoot into the sea. An amphibious bus service, was it? An inch or two free of land they start to arc, as though compensating for the curvature of the earth, and become obvious boat trips, ending up at the Isle of Man, Skye, Eigg, Wight.

Within these islands, none of the roads are shaded.

Why else would Simon have gone to those isolated spots, except to cover all roads?

‘Have these islands got a mental tick beside them?’

‘No.’

The sticker on the cover of the atlas said £6.99. ‘Actually, it was £1.99 in Budgens,’ he confessed, folding the book shut, delighted at the low cost of pricelessness. Then he picked up his map again, darted glances through the windows on either side of the carriage to remember his point of departure from three dimensions, and slid back into silence.

Fretful with impatience, Simon bustled down Woking platform as fast as his holdall and gout would permit, noted with satisfaction that the local bus service was three minutes late and, worried that those minutes might suddenly pick on us instead and delay all his plans, made quickly for the centre of town with me trotting behind.

The Martian is at the end of a dreary pedestrian walkway, its legs buckled with despair at finding that it’s travelled sixty million miles, the last hope of a dying civilisation, and ended up in Woking. In Woking, being (as the photo shows) punched by a lamp post and chased by fake Victorian bollards.

Standing on a coloured microbe, Simon admired the sculpture, consulted a street map and ate a pack of Bombay mix he’d found wandering about his bag.

‘Do you like this Martian?’ I asked.

‘It’s all right,’ he said.

‘Do you like Woking?’

‘H  . It’s all right. When I got older, I used my grandmother as my springboard. I used her to bounce all over the South-West.’

. It’s all right. When I got older, I used my grandmother as my springboard. I used her to bounce all over the South-West.’

We walked up the hill, and through a brick gateway into a private compound of 1930s houses, set, as in the American Midwest, among redwoods. The private roads rested on grass, between daffodils; the buildings, three times the size of city houses, were stockaded by laurel hedgerows and topiary yews.

‘H  (with contentment) this is it, my grandmother’s house,’ announced Simon.

(with contentment) this is it, my grandmother’s house,’ announced Simon.

But the moment we stepped in to look around, Simon got frightened that we were trespassing, and ran away.