When Noël was still two the doctor pronounced that his brain was much in advance of his body and advised that he should be left very quiet, that all his curls should be cut off and that he was to go to no parties.

Cole Lesley, The Life of Noël Coward (1976)

‘Two, two, two …’

Simon, have you had a stroke?

‘Two, two …’

We were sitting in the Excavation, Simon eating Mackerel Norton again, but this time the authentic version, with Chinese-flavour packet rice. The stench creosoted your lungs. It’s as though Batchelor’s has thrown the Chinaman in with the rice. I was in the middle of the room, balanced on a dining chair that often drifts on the sea of rubbish, several feet north of the corner clothes cupboard. Simon was rocking on his bed, the stained and crumpled blankets pushed aside, his eyes crimped with delight.

‘… two, two, two …’

Simon! What’s going on?

He forked up more fillet and boiled Chinaman from the plate on his lap. ‘… two, two, two …’ exhaled in a cloud of fishy bits.

Somebody shoot him!

‘… two, two, two, two …’ cried Simon, louder.

Simon’s first ever mathematical memory is of sitting on his parents’ sofa, working out the value of two to the power of thirty, that is:

2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 = 230

He doesn’t know why he started this snake of digits. He remembers not being able to stop. One moment he was fidgeting quietly on the sofa cushions; the next he was soaring into the stratosphere of the thousands, and lo! ‘My life as a mathematician had begun.’

2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 = 210 = 1,024

2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 = 211 = 2,048

2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 = 212 = 4,096 …

He still likes twos. He enjoys how they underpin half the number system, and the rest of mathematics teeters on top.

‘… two, two …’

The Monster (as Simon deftly observes) is (take a deep breath) ‘a group of characteristic 2 type, with involution centraliser, structure 21+24Co1, where the group at the bottom of the normal series of the centraliser is of order 2; the group in the middle of order 224, and if one divides the order of the top group of the series by that of the Conway Group, one gets 225’.

That day, sunk in his mother’s sofa, he noticed that 225 (which is to say two, multiplied by itself twenty-five times over) equals 33,554,432, ‘and I liked the fact that it began with three pairs of digits’.

‘… two, two, two …’ he continues now.

Stop, Simon!

‘… two to the twenty-six, two, two, two …’ he sped up. ‘TWO!’

Deflated with satisfaction, he downed three congratulatory mouthfuls and bounced his lips to endure the heat.

‘Two to the power of thirty is one, oh, seven, three, seven, four, one, eight, two, four.’ Above the mid-hundred thousands, Simon rarely calls a number by its full name. He raises his eyes up and slightly to the right, and reads each digit off, as though they floated there, projected out of his mind onto a screen in the sky. ‘Excuse me, this rice is too hot. Can I use that napkin to blow my nose?’

When Simon first did this multiplication as a child, he liked the patterns the numbers made.

‘What do you mean, “patterns”?’

‘Two to the power of twenty-three was my favourite’:

2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 = 223 = 8,388,608

‘Why?’

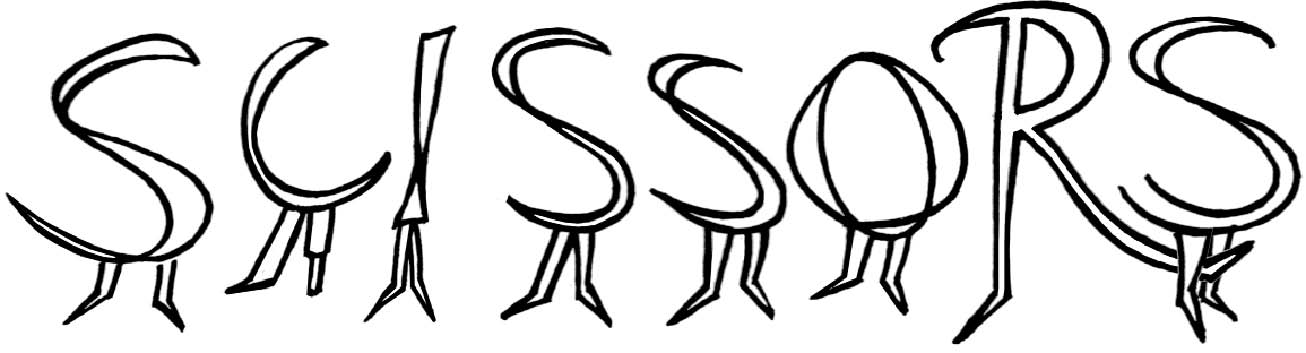

‘It spelled “sissors”.’

Mathematics is the study of patterns. We use the word ‘two’ to describe the pattern of ‘twoness’ – the pattern we see if someone shows us first two of Simon’s socks with holes, then two empty mackerel tins, next two bus tickets to an orchid lecture in Pembrokeshire, after that two plastic bags of British Rail ‘Weekend Rover’ holiday brochures bought in Torbay … The existence of this ‘twoness’ pattern (and also the patterns for ‘oneness’, ‘threeness’, ‘forty-sevenness’, etc.) gradually led primordial man to develop the idea of a sequence of whole numbers, stretching from the small values, such as 1, 2 and 3, needed to tot up woolly mammoths and caves, through the midland quantities – 10, 15, 20 – better suited for sheep and birds’ eggs, and on to the infinite reaches of God.

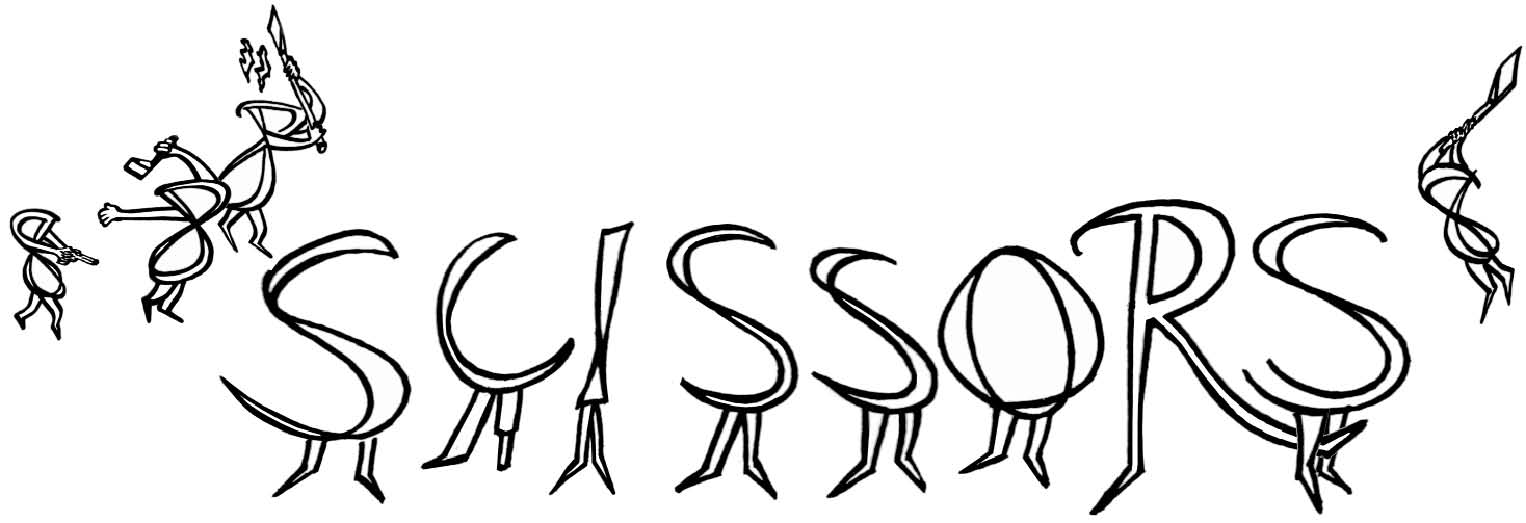

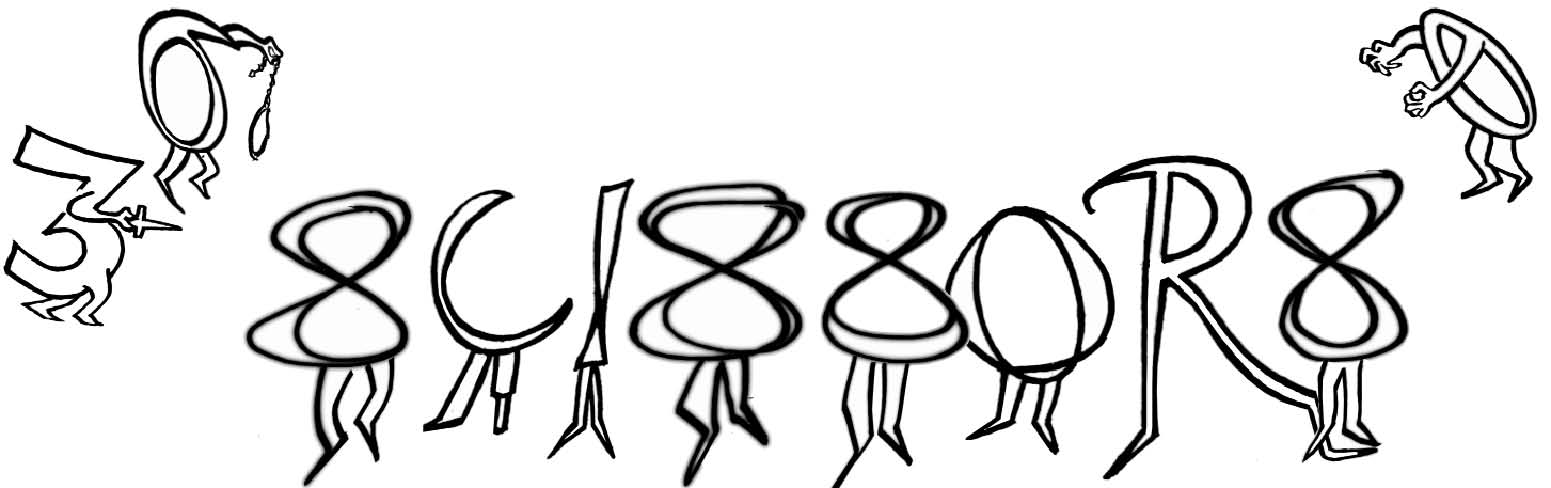

What Simon means by saying that he likes the ‘pattern’ that two to the power of twenty-three made ‘because it spells “sissors”’, is that the answer:

223 = 8,388,608

has its digits set out in the same arrangement as the letters in the word ‘scissors’.

Replace the S’s with eights:

And let 3, 6 and 0 swap with the remaining letters, as appropriate:

‘So you see,’ said Simon, who had meanwhile gone to the kitchen for more supper, ‘8,388,608 therefore has the same form as –’

‘No it doesn’t,’ I interrupted. ‘It can’t spell “scissors” because it still leaves the “c” unaccounted for. 8,388,608 has seven digits, and “scissors” has eight letters.’

‘It does when you spell “scissors” the way I did: S-I-S-S-O-R-S.’

‘But that’s cheating! I could make any number I like equal any word if I took that approach. It makes a nonsense of the whole game.’

Simon re-emerged from the kitchen in a fresh waft of headless fish and boiled Chinaman.

‘It doesn’t when you’re four.’

Another puzzle-book game Simon played as a child – utterly pointless, vital to his mathematical development – was to turn phrases into sums. It’s important to understand how these games work. They’re the next step up from ‘sissors’, and they confirm (I think) the arrival of something critical – a sort of mischievous joy, a playfulness; I’m not quite sure what to call it – to Simon’s genius.

Simon’s love of mathematics as a child had nothing to do with logic. It was aesthetic and jocular. He enjoyed the subject in the same way a theatre-goer applauds an energetic musical.

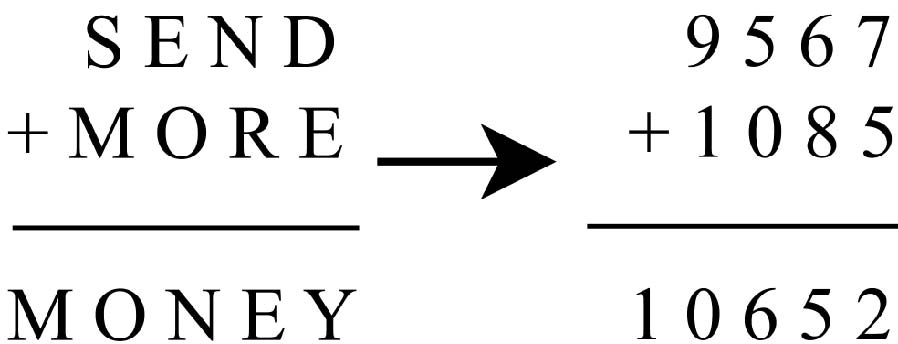

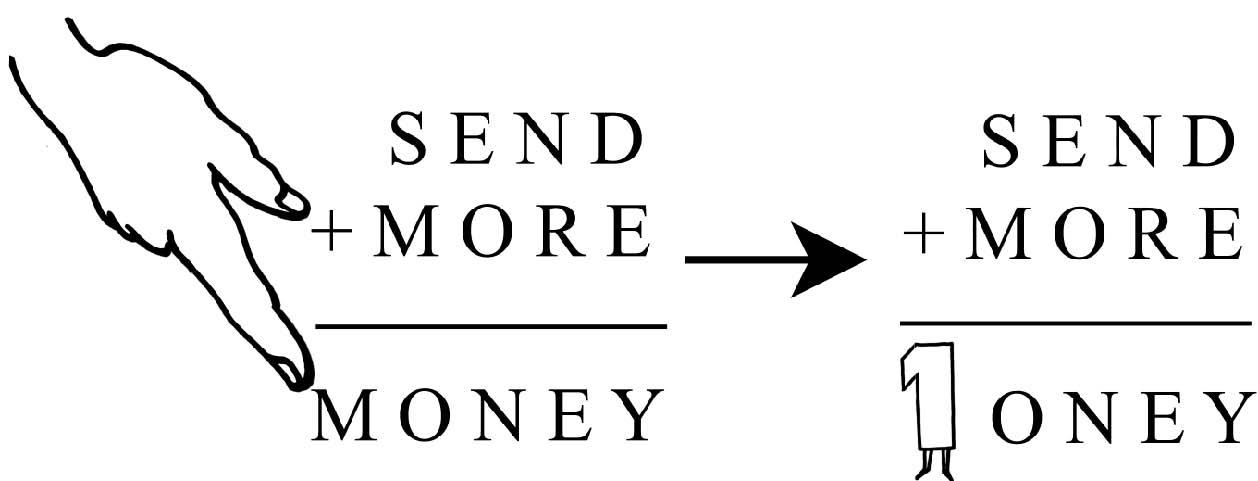

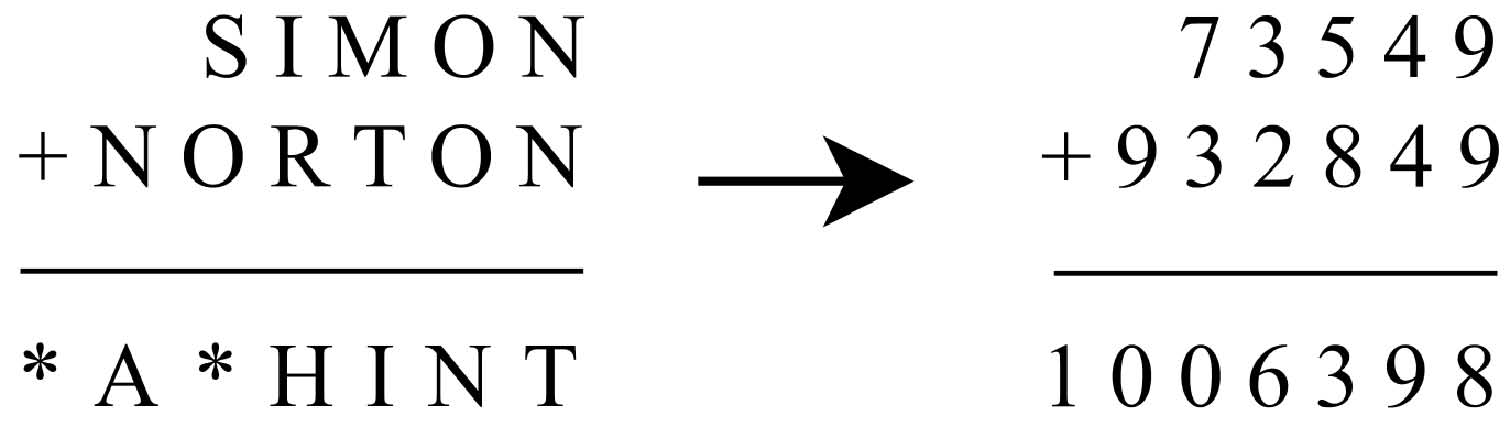

The most famous phrase-into-sum was invented in 1924 by Henry Dudeney, a civil servant:

The aim is to replace each letter with a unique number, and make the sum come out right. After a great deal of shredded paper and pencils hurled at the wall, you discover that the only possible substitution is:

These puzzles are like one of Simon’s anecdotes. Just when you think you’re getting somewhere, they’re abruptly over and you’re nowhere at all. The intriguing message you started with (why ‘SEND MORE MONEY’? Is Mr Dudeney on the run from the police? Is he kidnapped, tied to a chair, with a pistol at his head?) turns abruptly to dust: it’s nothing more than 9,567 + 1,085 = 10,652. So what? You’re winded of excitement.

Computers are ideally suited to this type of puzzle. They chew through all the options for the letters at vast speed, and spit out the answer in milliseconds. The good schoolchild puzzler likes to discover shortcuts. He wants to exploit patterns to help him out. The most important thing is not the answer, but reaching the answer with slyness. He wants to creep round the back of the puzzle and give it a sharp pinch; then he’ll puff up his chest, pull at his shirt collar and consider himself a clever swell. A good mathematician has a lot in common with a seaside hoodlum.

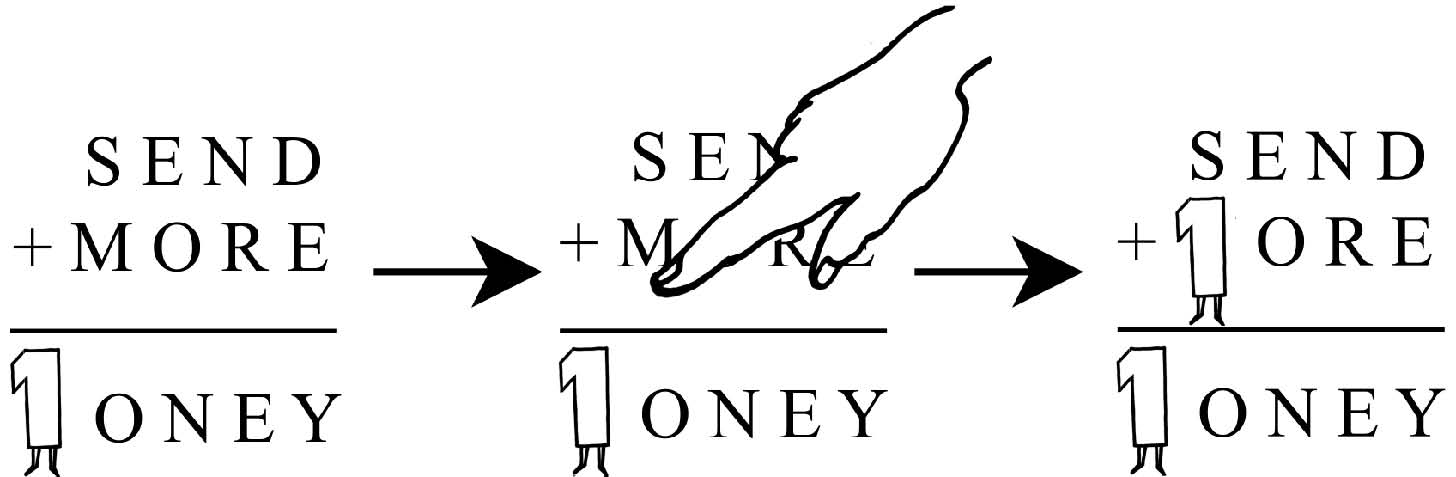

Immediately, for example, he can tell that the ‘M’ in ‘MONEY’ must equal 1. This exploits a basic pattern in elementary arithmetic. If you take two single-digit numbers – say, 8 and 3,

that add together

to give a two-digit number

then that longer number will always begin with a 1 (3 + 8 = 11).

Like so many rules in arithmetic, this sounds fastidious and clunky when described at length, but in fact everybody knows it instinctively. It’s the rule that makes you furrow your brow when you’re being cheated at the coffee shop. ‘Three quid for a croissant and £8 for a cappuccino makes forty WHAT?’

The ‘M’ of ‘MONEY’ in the word puzzle must therefore be equal to 1.

If it didn’t equal 1, a pattern of mathematics would be broken, gout pills would walk by themselves, buses fly on wings, headless fish leap up from their tins and chase Simon around the kitchen. And if that ‘M’ must be a ‘1’, then (by the rules of the game) so must the other ‘M’:

And so on. Pinch by pinch, the mathematician pesters the puzzle until it bursts into tears.

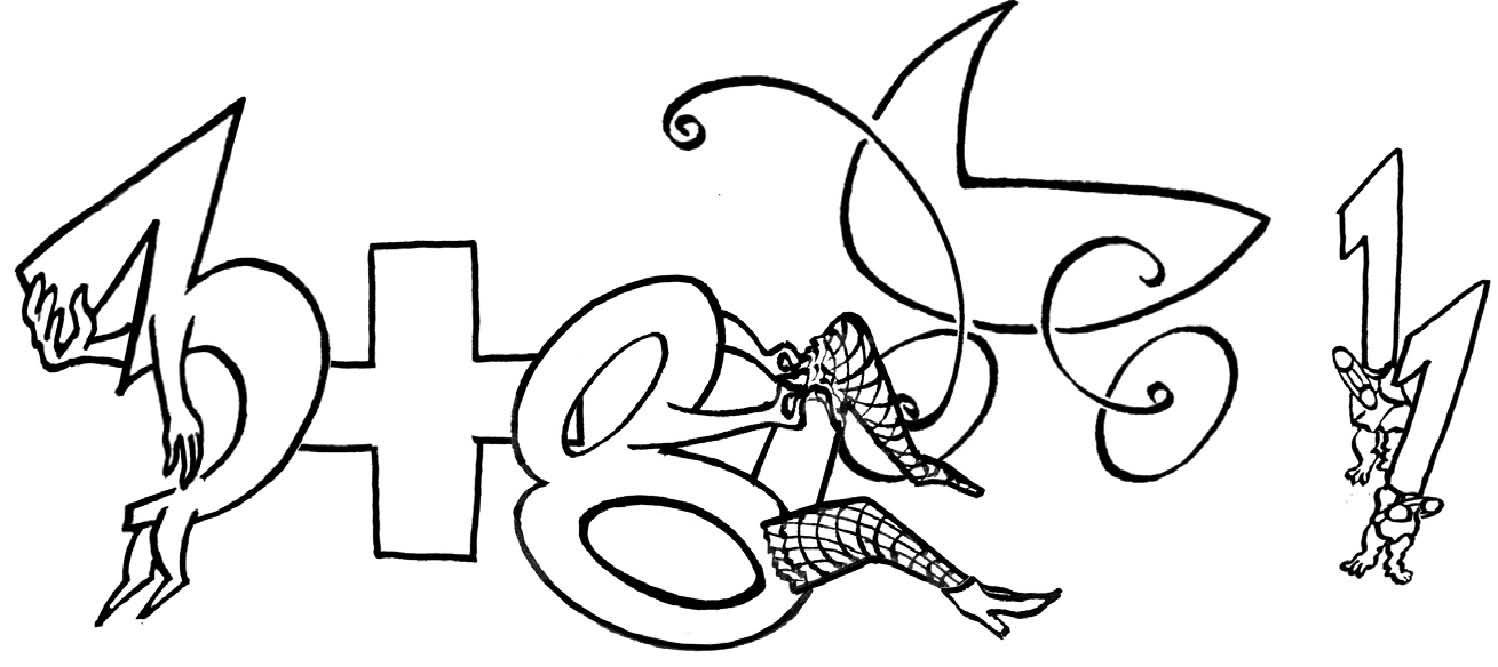

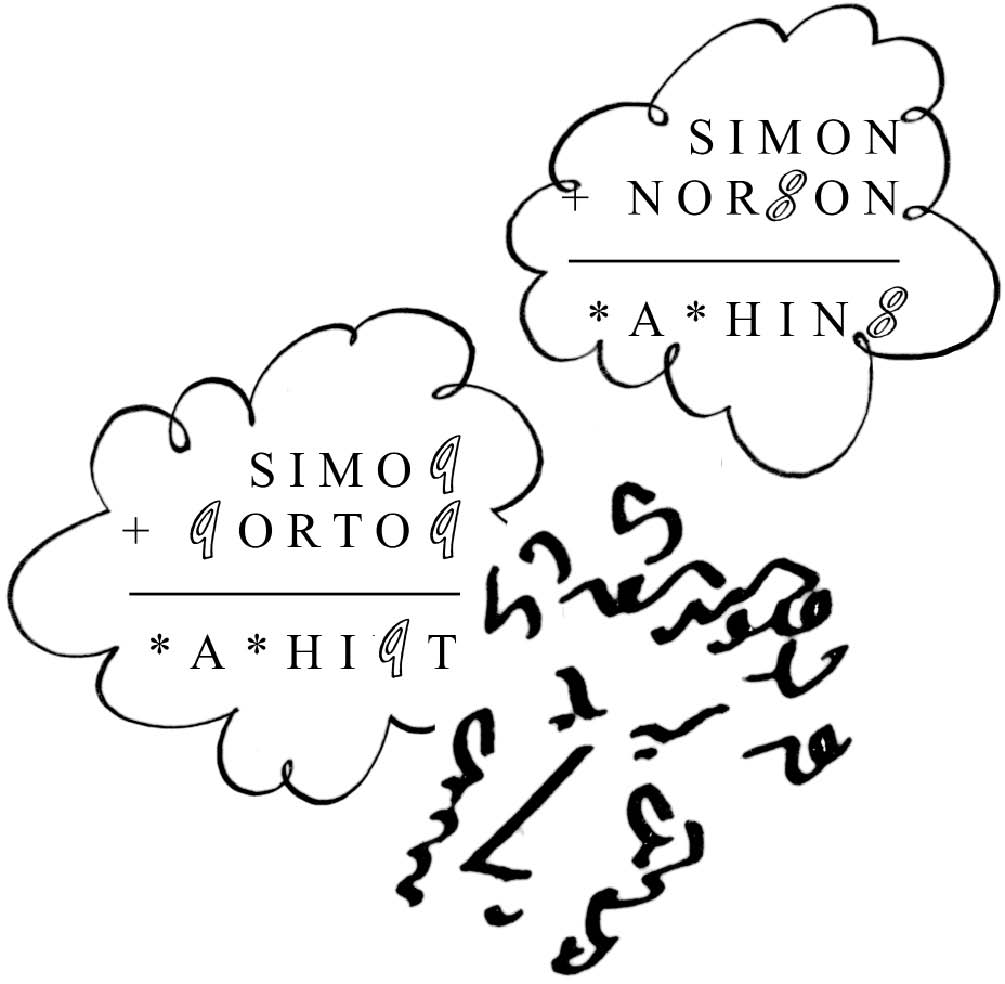

The first puzzle of this type that Simon invented, as a schoolboy, was:

Which is feeble. The words should make up an interesting phrase. Why is Simon Norton a hint? A hint at what? And what are those stars doing there? These puzzles are supposed to stick to ordinary letters. You can’t go adding stars to the alphabet (and allow them to stand for different digits – outrageous!) just because you can’t find something between A and Z to suit your purpose. But Simon was too amused by the chase after numbers to worry about that. SIMON + NORTON = NO*HINT would be closer to the mark.

Simon can solve these puzzles with startling speed.

‘Don’t you have to think about it at all?’

‘No.’

‘You just know it? You can see instantly that the letter N must be a 9?’

‘Yes.’

‘It is somehow obvious to you at first glance that T will be an 8?’

‘Yes.’

‘“Obvious” in a logical sense,’ I asked, ‘or “obvious” in the sense of a sensation? Would you feel distressed as if you’d eaten a mouldy tomato …’

‘A raw one is disgusting enough.’

‘… if someone suggested T might be 2, or 7?’

Simon looked perplexed. ‘This is a general phenomenon, isn’t it? When one does something often enough one learns how to do it without conscious thought.’

‘But there’s a difference. Do something quickly because practice has made calculation easy, or do something quickly because you don’t need to calculate. The second is divination. That’s genius.’

‘Huunnh,’ Simon grunted, and stabbed at his fish in distress.

I’d read once about a journalist who’d decided to learn the trick of calculating the day of the week, for any date.

‘15 July 1843?’ you would ask.

He’d reply, ‘Saturday.’

‘30 December 2076?’

‘Wednesday.’

‘19 March 12,693 BC?’

The formula was easy. He memorised it in an evening. Daily practice made his speed increase. In a month or two he could answer any question in ten seconds. What took time was the arrival of fluency, the ability to think without thinking: to be able to do the calculation so readily that even to himself no calculation appeared to be involved. That took three years.

After that, for this journalist, 12 October 1646 was no longer a Friday because the numbers said so, but because it could not conceivably be anything else. ‘Friday’ was the only possible word that evoked the sensation of ‘12 October 1646’. It would be as foolish to mention ‘Tuesday’ as it would be to put salt on your ice cream.

Is this what happened to Simon? Did his obsession with calculating two to the power of thirty when he was four years old rearrange the neurons in his brain (achieving in an afternoon what took the journalist three years – brains are so much more flexible at four years old) so that certain number problems became effortless after that – more a matter of sensation than calculation?

But this clumsy struggle to put my question into words had taken my focus off Simon. When I looked back at him now, he had put his plate to one side and was perched forward on his mattress, neck shrunk in, eyes staring straight ahead.

‘Is that knocking?’ he grunted. ‘Someone’s at the door.’

‘Never mind that. We’re homing in on the origin of genius. “Sissors”, calculating all those twos and finding patterns, phrase-into-sum puzzles – as I see it, the essential elements are a) playfulness, b) visual satisfaction, which would have made any attempt to force mathematical learning on you, like those ghastly aspirational parents, destructive by removing natural enjoyment, and c) –’

‘The door!’ Simon bounced up and down in frustration. The plate and cutlery clattered half a beat behind. ‘Someone is knocking!’ he cried.

‘– and c)’ I pursued, ‘utter self-centredness. Get the bloody door yourself.’