Dr Parker: To prove something ‘in the sense of Simon’ is to do a proof without doing it at all. You just know the answer will come out right without having to do any calculation.

Me: Can you give me an example of this that I could understand?

Dr Parker: Wooooooo! … no … no, nothing so simple as that.

Dr Richard Parker, Simon’s former colleague,

in conversation with the author

Simon has dismissed himself from his Cambridge history. He hurried about the city during these student years with such a platter-faced lack of awareness that (from the point of view of his biographer) it’s possible he wasn’t there at all.

‘But your own history! How can you eliminate that?’ I say. ‘Are you a person or a fog?’

‘Ahhh, have you seen this?’ says Simon, putting down his latest garbage bag. (There is now a clear view of carpet stretching from the kitchen to the main door.) It’s a till receipt for a book called The Messianic Legacy. The purchase entry reads: ‘Messy Legs … £8.00.’

Simon’s life during the period in which he was a student and a world-leading young research fellow is like a film in which a minor character has been removed from the celluloid with a Stanley knife. Other figures start back from his hollowness, tiptoe away from his vacuity, whisper behind a back that isn’t there. There was none of that noisy, gawky scrabble to establish a character for himself that makes other young men such memorable bores. Simon aged twenty was in extremis what Simon is being today, at fifty-eight: a gathering of emptiness. His old classmates were thrilled to know this famous genius was in their year; delighted to be counted among his admirers and conversationalists; overjoyed to point him out to their baffled parents when they spotted him scraping along the wall towards the Mathematics Faculty with a sequence of plastic bags on his arm (this was before he discovered the existence of holdalls) – but as a man they barely remember him.

‘He had this hermetic life,’ says Professor Bernard Silverman, now a Fellow of the Royal Society and former Master of St Peter’s College, Oxford. ‘At an angle to the rest of the world.’

‘Recently, I looked him up in Who’s Who, and when I didn’t find him, I assumed he’d finally got run over,’ recollects Raymond Keene, who became England’s second-ever chess grandmaster. ‘Our main concern was making sure he got to chess matches without getting knocked down, because he was always looking at his feet as he was about to cross the road.’

Lee Hsien Loong, now Prime Minister of Singapore, and the second-best student mathematician at Trinity after Simon, ‘feels he did not know Dr Simon Norton sufficiently well, and it would not be appropriate for him to do this [i.e. comment]’.

‘But what sort of person was he? Did people like him? Who were his friends?’

‘Of course people liked him,’ soothes Nick Wedd, who went up to Cambridge the same year as Simon, to study natural sciences. ‘Why would you not like Simon? What was there not to like?’ For a giggle, he and Professor Silverman broke into Simon’s rooms in Trinity once. ‘But we didn’t find anything there, either.’

Grandmaster Keene rings up with a new recollection. If I bring him a ten-shilling note next time I’m in Clapham – a used note, not a fresh one – he will recreate it for me.

‘As Simon walked around,’ explains Keene when I arrive with the money, ‘he used to pester the note, like this:’

Keene also contributes the astonishing information that Simon wore a suit during these years.

‘Don’t make me laugh!’ I reply, outraged. ‘He wouldn’t know how to get into a suit. He’d put his feet in the armholes. His head would appear out of a trouser leg.’

‘And a tie,’ insists Keene.

Simon too looks dubious about this piece of information.

His brother Michael remembers that as a child Simon invented an idea called ‘Vortex Theory’. According to Vortex Theory, one step in the wrong sartorial direction – e.g. buying a new pair of trousers when there are still two days left in the old ones before the police file indecency charges – and the Vortex will get you. A second later you’ll be swirling down Saville Row in a frenzy of designer suits and Gucci tiepins.

(Simon: ‘“Savile”, not “Saville”. I may despise the products of Savile Row, but not so much as to want to misspell the name.’)

However, Keene’s evidence does explain a mystery of the Excavation: why there is a clothes cupboard in the front room (wedged against a groyne halfway along the south wall) containing, sodden with mould, three jackets and a dressing gown. The thin filaments growing along the fibres of the gown are different to the fried-egg splatters sucking on the jackets.

At the base of this cupboard, a swell of floor clutter has washed in and left a puddle: three shoes and an Asda bag of Norwegian swimming brochures featuring young ladies.

‘As I say,’ continues Simon, inspired by this flurry of my historical investigation, ‘I do remember one other fact pertaining to my habits of the period …’ He stretches his back as though limbering up for a shocking revelation: ‘I was always a great Twiglet eater.’

Then he returns to sorting through a pylon of colourful leaflets by the cupboard. ‘I think this pressure you are putting on me may be creating a domino effect. One memory seems to be coming quickly after another now.’

While at Cambridge as a student, Simon also developed a dislike of cows ‘when of the female sex’.

His habit of scraping along walls as he walked was not because he was trying to keep in contact with it; he was avoiding the middle of the pavement, although he can’t explain why he should have wanted to do this.

He adopted a new word: ‘ooze’.

‘What did it mean?’

‘Agggh, hunnnh, I don’t know.’

‘Ooze’: it was between an interjection and a sigh.

‘Where did you make it up from? The river Ouse in Yorkshire? “Ooze” as in what mud does?’

‘I can’t remember.’

‘Well, how did you spell it?’

‘I never spell it.’

Thumping down medieval wooden stairs from his college rooms at every opportunity, past the students lounging about on the lawn with Cava and strawberries, Simon hauled his plastic bags through streams of cyclists on King’s Parade – and dropped himself into the first bus at the Drummer Street terminus that would fling him into distant Britain: the glens of Scotland, the tin fields of Cornwall, the glittering lakes of Cumbria.

After his first term Simon rushed back to London and calmed his jitters with a twelve-mile Ramblers’ Association walk around Meopham. He still has the leaflet stored in a box file, on the oddly tidy shelves in the back room of the Excavation. ‘On behalf of British Rail,’ it announces, ‘we apologise to the participants on the last trip who had to leap out of the train next to the Live Rail and remove a fallen tree.’

Simon joined an excursion group: the Merry Makers, a British Rail club run by an energetic fellow who claimed at the top of the letter that he was the Area Manager of Watford Junction train station – but signed himself off at the bottom, in a mumble, as the Commercial Assistant. Saturday Sprees! Holiday Previews! Spring Tours! Pied Piper Seaside Specials! Simon leapt on them all.

‘The two things,’ he says, ‘that I would recommend to anyone who is lonely: politics and public transport.’

Suntan Tours! Autumn Tours! Mystery Tours (Mini, Midi or Maxi!) ‘Hello, you may already be a “Merry-Maker” and I am sure you will not be able to resist becoming a “Happy Wanderer” too!’

It was during this period that he developed his distinctive technique for introducing himself to strangers.

He locates a bunch of people he likes the look of, looms at the fringe of their conversation until his quick mind spots a link between a passing topic and a place he’s visited recently, then he whips out his wallet, extracts the relevant ticket and jumps aboard. Lo! He’s with you, rattling along on the conversation.

‘Haaa, hnnnn, have you seen this? [Hands round a travel docket from, say, Pershore.] I thought you might be interested because you were talking about Anthony Powell and earlier mentioned the village of Wyre Piddle…’

Simon looks semi-idiotic at these moments. But he’s the opposite – while you’re presuming that he’s lost his marbles, he’s waiting for you to spot the three or four links connecting Piddle and Powell. Piddle is next to Pershore railway station, Worcestershire; last week Simon made the journey from Piddle via Pershore to Frome; Frome is where Anthony Powell had his house ‘The Chantry’ and wrote A Dance to the Music of Time.

It’s quite possible that Simon has read a novel by Powell (despite Simon’s insistence that he dislikes all serious literature), and could have joined in with a sharp comment about one of the characters, but if he can get to the topic this roundabout way, on public transport, he feels vastly happy.

When I have a party in my rooms, Simon stomps upstairs bringing a very thick train timetable – the thickest possible: one for the whole of Europe or America. Most people think this is because he can’t bear to tear himself away from his closed-off world of public-transport obsessiveness. In fact, it’s to give him more ways to escape his closed-off world: it’s in case his ticket collection isn’t enough. He wants to be able to use all the information in the book, as well as all that in his wallet, as possible links. As he walks around the room, lurking at the edges of the groups, listening out for conversations that interest him, he keeps one finger stuck among the pages, halfway through, so that the moment he hears a cue-word he can snap the book open, spin through the sections, and have the relevant timetable up and pushing aside everyone’s wine glass before the topic has moved on.

‘Aaah, uugh … have you seen this? [Shows a timetable to Heathrow, interrupting a conversation about glass eyes.] As I say, that reminded me that I once gave £10,000 to the man who superglued himself to Gordon Brown.’

‘Thank you, Simon.’

‘AAAhnnh, as I say, his name was Dan Glass. He is a founder of the activist organisation Plane Stupid, which protests against the expansion of Heathrow.’1

The winter term of Simon’s second year at Cambridge arrived: the Garden House riots. A thousand students drummed on the windows of this local fancy hotel and invaded the kleftika course during a visit by a delegation of fascist Greek generals. Nine arrested, dons reprimanded – the most famous student political event of the decade. Where was Simon? On a bus.

(‘Alex, I would like you to add at this point: “Today Simon’s main association with the hotel is disgust at how the view from the riverside walk opposite was spoilt by a car park.”’)

Spring term showed up: rain, grey skies, late nights at the library, brandy and muffins in the Junior Common Room. Simon? At Leicester Central train station. It’s his eighteenth birthday: 28 February 1970. He’s standing outside in the desolate cold, wondering what to do because the connection he’d planned to take to Rugby Central, as a birthday present to himself, has been shut down.

Simon can remember buses and trains he took during his time at Cambridge with astounding precision; it’s everything else that’s vanished: ‘I started on the 06.33 train to St Ives, a line that was soon to close. At St Ives I got on a bus to Huntingdon, then by train to Leicester via Peterborough. I spent most of the day looking round the city but can’t remember anything about what I saw.’ Summer came: silken, bra-less string tops and miniskirts – oh! Summer, in Cambridge, for boys! … Simon? Barrow-on-Furness. Eyes on toes. Stuck in a train tunnel.

He drank orange squash. The chest under the mantelpiece still has a drawer packed with empty Tango bottles, twenty years too old to return for the 2p deposit.

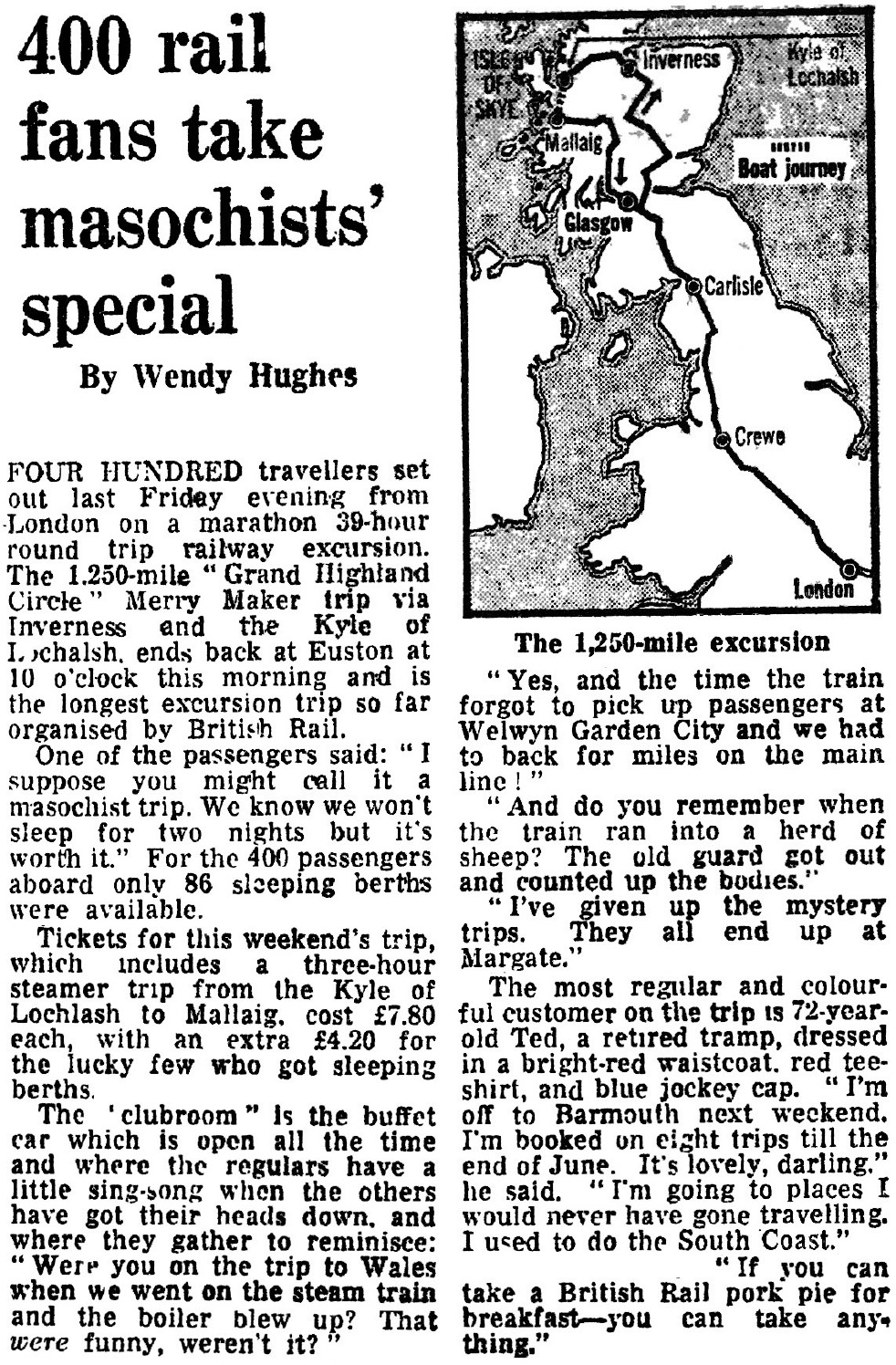

He went on the Masochists’ Special. Simon’s still got the clipping, pressed tidily inside a B.D. (Before De-regulation) box file in the back room.

Why did he find these trips necessary? What did they have that was better than college life? What could he do on them, aside from pay ten pence to sit above a bus diesel engine with farmers’ wives and shrieking schoolchildren? Was he being metaphorical? As in, buses depend on timetables; timetables depend on numbers and patterns: therefore, taking buses equals travelling through maths? Was he being that weird?

‘Oh dear!’ Simon complains. ‘Is joy such a hard concept to understand?’ Hadn’t I (he points at me) admitted that I used to pick up paper squares that somebody had spat on, and called it ‘stamp collecting’? Other people like to drop out of aeroplanes at 10,000 feet, dangling from coloured bedsheets. Simon zipped through the countryside in metal worms.

But …

Clipping abridged by the biographer. Source unknown.

Please! Go away, biographer! That’s enough! How much more do you need to be told? Look at Loch Lomond and Glen Coe swish past! See the valleys of Devon plunge and weave! Watch out, stand back! Here comes Simon, aged twenty-one years, seven months and four weeks, out of Llandudno on a Number 47, racing up Snowdonia, through Llanberis Pass.

Wheeeee! Over the hill! Rushing to the embrace of Colwyn Bay; looking out to the Celtic and light-splitting sea.

‘Nevertheless, Simon,’ I keep at him, ‘if day trips were the only way you enjoyed spending your spare time during this period, why don’t you remember anything about the scenery or stories that took place? Why nothing except the bus numbers and connection times?’

‘Oh dear, oh dear, does everything have to have such a ridiculous reason? I liked taking trips, that’s all. Why ruin it with words?’

One of two box files of tickets from the early Cambridge years, found in the back room.

1. Campaigner ‘glues himself to PM’

A campaigner against Heathrow Airport’s third runway has attempted to glue himself to Gordon Brown at a Downing Street reception.

Dan Glass, a member of Plane Stupid, was about to receive an award from the prime minister when he stuck out his superglued hand and touched his sleeve.

Plane Stupid says Mr Glass, from north London, then ‘glued his hand’ to Mr Brown’s jacket as he shook his hand. But Downing Street said there had been ‘no stickiness of any significance’.

Plane Stupid recently gained publicity by mounting a protest on the roof of Parliament. Spokesman Graham Thompson said Mr Glass – a 24-year-old post-graduate student at Strathclyde University – had smuggled a small amount of glue through Downing Street security checks in his underwear at about 1700 BST.

He met the prime minister during the reception at about 1830 BST.

Mr Thompson said his organisation was attempting to make Mr Brown ‘stick to his environmental promises’ (news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7520401.stm).

The award Dan Glass received is funded by Simon. Every year, very quietly – it’s appropriate to reveal it in a footnote – Simon gives £10,000 to the Sheila McKechnie Foundation to sponsor their Campaign Award for transport activism (www.smk.org.uk/transport-2008/).