With the Moonshine Conjectures, which Simon played such a large part in formulating, it was as though Simon opened the door between two very strange areas of maths but decided not to go through it.

Umar Salam

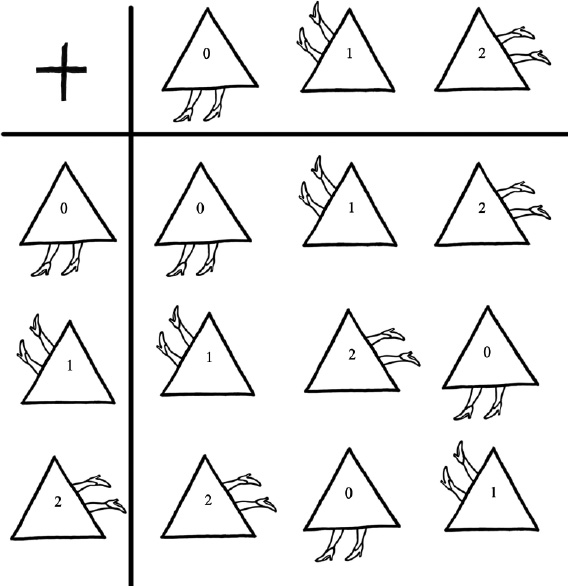

The symmetries of Triangle, and the way they interact with each other, can be written out as a Group Table with three columns and three rows:

The symmetries of Square have a Group Table with four columns and four rows. The symmetries of a garbage-bag-being-kicked-about-with-three-pieces-of-rubbish-inside result in the six-by-six Garbage Bag Group Table. But what is the monster whose symmetries are documented in the Monster Group Table, with its

808,017,424,794,512,875,886,459,904,961,710,757,005,754,

368,000,000,000

columns and

808,017,424,794,512,875,886,459,904,961,710,757,005,754,

368,000,000,000 rows?

Simon doesn’t know.

For reasons inexplicable to biographers, he knows that it lives in 196,883 dimensions.

But he can’t explain why.

In 1979, Simon and Professor Conway discovered another thing about this mysterious monstrous object. The result was so shocking, so astounding, so contrary to what anybody expected, that they called the discovery ‘Monstrous Moonshine’.

But Simon can’t explain what Monstrous Moonshine is either, not in any language that I understand. Each time he tries, I feel depressed.

I think how it goes is like this. In 1979, John McKay, a mathematician in Canada, whose office is so messy that he once lost his baby son among the papers, discovered a remarkable coincidence. The set of numbers that explains why any object that has the Monster Group of symmetries must live in at least 196,883 dimensions cropped up in another, entirely unrelated, area of mathematics.

‘Huugh, aaah, no. Alex, you’ve got that not quite right. What McKay discovered was that the Fourier expansion of the j-function, j(tau), where tau is the half period ratio, has as its first coefficient 196,884 …’

‘196,884,’ I point out with admirable speed. ‘Not 196,883, then?’

‘Exactly. That’s the point. 196,883 + 1 = 196,884, so that shows that in 196,883 dimensions …’

John McKay sent Conway a postcard explaining his discovery. Fortunately for Conway, when the card arrived Simon was away on a two-week jaunt around the railways of England. By the time Simon got back, Conway had made significant progress towards explaining the astonishing coincidences, otherwise the Monstrous Moonshine Conjectures might have been entirely Simon’s work.

‘Hnnnnhh, no. That’s not correct either. No one has explained it satisfactorily! What Conway and I did, as I say … aaah, let me see … perhaps … I should begin by explaining what hyperbolic geometry is. If, uuugh, I put this map on the ground to represent aaaah, huunh … Euclidean geometry …’

‘Thank God I had that two-week head start on Simon,’ Conway is quoted as saying in Finding Moonshine, Marcus du Sautoy’s book on the subject, ‘else I wouldn’t have got a look-in!’

For me, the familiar panic sets in at this point, and instead of having the sense to make Simon go back over anything I don’t understand, I narrow my eyes, try to look as if I’m savouring each new theoretical observation with the enjoyment of a sage, and feel the earth slip away.

‘I think of myself,’ says Simon proudly, ‘as a fixer.’

His campaigning letters to the local MP, badgering of government ministers about timetabling, demonstrations in Cambridge concerning the new guided-bus scheme, protest meetings about traffic-easing schemes for cars on the A14 that could be just as readily achieved by providing three wiggly buses from Cambourne plus a double-decker to Six Mile Bottom – in all these cases, Simon sees his role as that of a person who spots flaws in the way public-transport numbers and schedules have been totted up, and ‘brings them to the attention of the best people available to have them corrected’.

‘You could also say I am a hub,’ Simon adds. ‘I pass the information out along the spokes. The people who make the actual changes and see that the machine works better as a consequence of what I have shown them, are the rim of the wheel. What you call my jaunts are part of this campaigning, because how else can I report on what is going on, except by experiencing it myself?’

‘And with the Monster and Monstrous Moonshine …? Is that what you think of yourself doing there too? You are still going over all the facts and calculations involved, spotting errors in the Group Table and reporting them to other mathematicians, being the fixer? You have, so to speak, not stepped through the door and got on with further profound mathematics, because you got distracted by the door frame?’

‘Yes, aaah, huunnh, I suppose so. As I say, I never understand you when you are philosophical. I don’t think you make sense. Incidentally, when I went to buy a new bag and hiking boots, the shop I usually use was a hole in the ground. But I have not thrown out the old pair. I’m keeping them to hand, in case a nail comes up.’

‘Thank you, Simon.’

Sitting in our cabin one night on our trip to Lapland, I tried another approach to get the subject back to understanding the Monster and Moonshine. I started talking about primes. Simple Groups such as the Monster – these atoms of symmetry – are often compared to primes because primes are numbers not divisible by any other number except one and themselves: primes are the ‘atoms’ or building blocks of numbers. 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13 … are all primes. 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12 … are not, because each is divisible by other numbers. E.g., 12 can be divided by 2, 3, 4 and 6. Every number in the infinite universe of numbers can be reached by multiplying primes together, but it can also be easily shown that there are an infinite number of primes …

‘Not necessarily,’ interrupted Simon. ‘Not if it’s a pring.’

‘What’s a pring?’

‘A ring. I invented prings.’

‘A pring is a ring?’

Simon nodded. ‘With power.’

‘So, what’s a ring?’

‘Uuugh, let’s see … if you have an, uugh …’ he began, with the same bright-eyed optimism with which he starts all his attempts at mathematical explanation with me, although for some reason the hesitancy had come back. ‘No, don’t interrupt, the quickest way to make progress with this is for you not to talk … if you have a mapping from R cross R into R, in the case of, a multiplicative and … no, I mean, given a binary operation on an algebraic structure that is a homomorphism …’

When Simon was awarded a mathematical fellowship at Cambridge it was (according to rumour) specifically added into the job description that he could have the post only if he promised never to teach.

This much I do know: Monstrous Moonshine links the Monster to distant mathematics and the structure of space in ways that are as awe-inspiring to a man like Simon as it would be to an astronaut to step out of his space machine on Jupiter, and find a Sainsbury’s bag floating past. That’s why it’s called ‘Moonshine’, because mathematicians can even now hardly believe it.

‘I think,’ said Simon, standing up from his berth and shaking crumbs and clotted blobs of oil and fish off his T-shirt onto the covers, ‘I can explain to you what Moonshine is in one sentence.’

When he really tries, Simon can be a model of clarity.

‘It is,’ he said, ‘the voice of God.’

Gold flakes bouncing in thick liquid are stars. Ultraviolet light makes blue shadows glow moonishly. Flashes of ginger and green are asteroids.

To ease the pain of another day of failing to understand Simon’s Moonshine Conjectures, I have invented a cocktail called ‘Monstrous Moonshine’. Two swigs induce a state of contented idiocy that’s similar to the look Simon has when he’s back from a week on the buses.

Monstrous Moonshine contains, in whatever proportions suit the torment of your mood (the given quantities below are a starting suggestion):

Recipe for Monstrous Moonshine

2 x Absinthe

1 x Blue curaçao

3 x Goldwasser

(‘Isn’t that a euphemism for urine?’ – Simon)

3 x Soda water

Lime juice, mint leaves and fresh ginger

A peeled lychee

Dry ice.

Mix the first seven ingredients, drop in the lychee, add dry ice (the drink will instantly start to boil with great violence) and drink in ultraviolet light through bared teeth.

Important Note for Historians of Cocktails: The absinthe is to represent moonlight – wormwood, the most important ingredient in absinthe, glows in ultraviolet light. Blue curaçao also glows in UV, and the colour suggests night. Goldwasser is the oldest liqueur in the world, invented in 1598, and tastes disgusting. You’d think that after 400 years of tinkering Goldwasser would be drinkable, but it isn’t. However, it contains flecks of real gold, which represent the stars. Lime juice is to offset the filthy taste of the Goldwasser.

The other trouble with Goldwasser is that the flakes don’t stay afloat. They sink to the bottom. Soda water makes them bounce about.

The lychee is, of course, the moon.

Dry ice is for monstrosity. I get mine from a Professor of Chemistry. You mustn’t use dry ice that comes from a nightclub machine. That’s toxic. The type you want comes in small, hazy pellets and will freeze a hole through your stomach if you swallow it.