Conclusion:

Global Democratic Theory and the Citizen

The impact of globalization on democracy and the nation-state has provoked a wide array of responses from democratic theorists. As we have seen in previous chapters, the approaches of liberal internationalism, cosmopolitan democracy, transnational deliberative democracy, social democracy, and radical democracy develop considerably different democratic ethics and therefore different accounts of how democracy ought to respond to globalization. While these approaches are drawn from distinct and pre-existing political theories, they are also part of common body of scholarship responding to globalization that is referred to in this book as global democratic theory. Despite the differences between these approaches, there are some recurring themes in the literature about the deficiencies of the prevailing form of liberal democracy located within the state, and the possibilities of promoting democracy at the global level by transforming global governance and enhancing the participation of transnational civil society. It is thus important to consider these approaches in relation to each other and establish more dialogue between the positions in order to advance these debates. Drawing on this scholarship, this conclusion considers the ways in which the approaches analyzed in this book can assist in the future realization of democracy in the contemporary age of globalization and global governance. Its main contention is that global democratic theory needs to deliver a range of practical perspectives that can help democratic leaders and citizens to critically rethink and redesign the organization of national and global governance. In order to demonstrate its value in this regard, the conclusion outlines the animating concerns of global democratic theory, its major areas of agreement and disagreement, and identifies the most important design choices on the paths toward a more democratic future on a global scale.

Global Democratic Theory

The importance of global democratic theory as a body of scholarship originates from widespread agreement among scholars of democratic theory, political theory and International Relations that globalization is challenging democracy within the nation-state and opening up new opportunities for participation in global governance. As such, global democratic theory shares with much of democratic and political theory an underlying appreciation of the value of public rule and an intent to create and enhance avenues for collective public action that avoid the dangers of oligarchy or dictatorship. The guiding concerns for global democratic theory are therefore to identify the problems that globalization poses for democracy and to articulate how existing processes and institutions can be changed in order to enable democratic politics with global horizons. Generally speaking, all scholars see the existing mechanisms of global governance as inadequate from their particular democratic perspective. But interestingly, for most scholars a common concern with avoiding the centralization of power and its oppressive tendencies also leads to a rejection of world government. This means that global democratic theory sits in a normative space between existing global governance and a prospective world government consisting of a range of perspectives that vary widely in their desired level of change. Liberal internationalism, for example, offers quite modest suggestions about reforming global governance to make it accountable to national democracies, whereas cosmopolitan democracy suggests quite significant changes to the scope of political community and the institutional architecture required for democracy to operate at a global level. The radical perspective of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri argues for more fundamental changes to the global order such as the eradication of sovereignty and capitalism in order to create a global anarchist democracy.

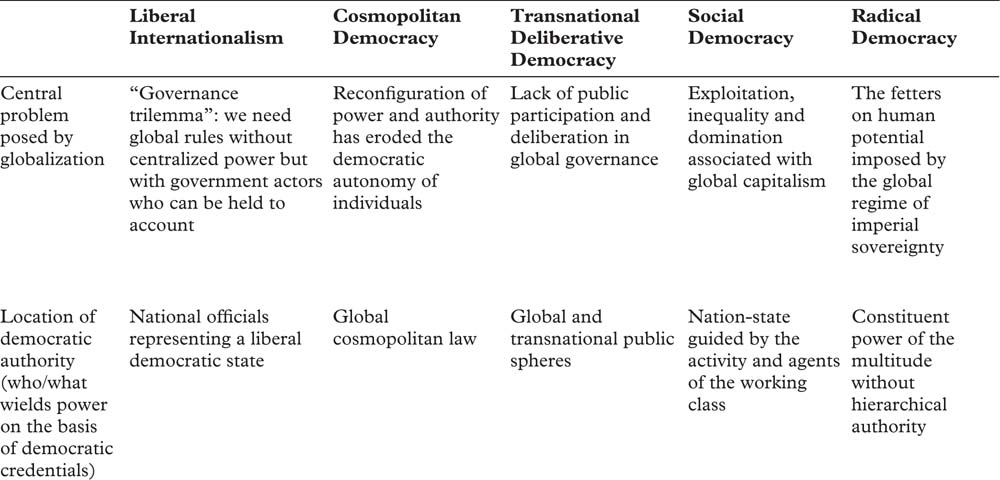

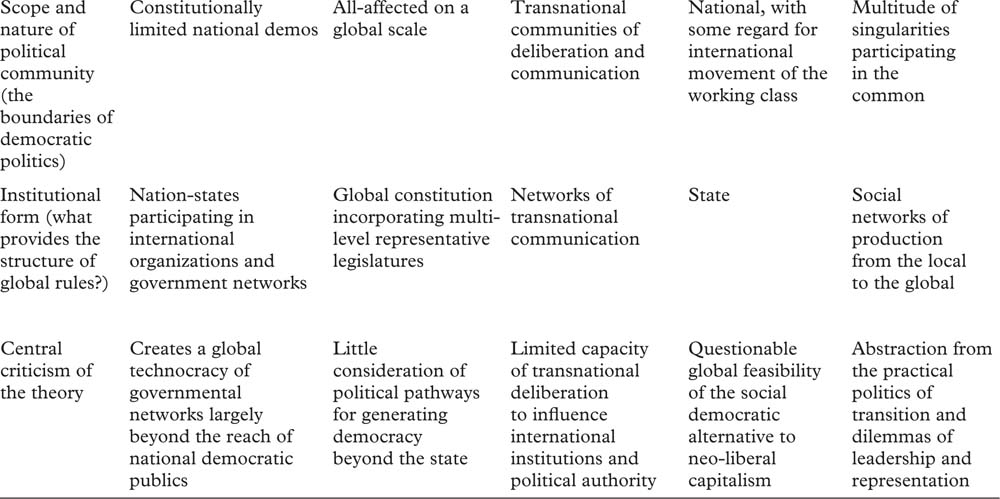

Global democratic theory is constituted by these different responses to the impact of globalization on democracy. The preceding chapters have examined the central problems that each approach seeks to address, outlined their key normative claims, and considered some of the prominent questions regarding their desirability and feasibility. As outlined in Table 1, what animates each approach is a distinct normative vision that defines the aspirations of democracy and leads to a particular vision of what democracy can and ought to look like. This involves some coherence around the core problem that globalization poses for democracy as well as normative claims regarding the location of democratic authority, the scope and nature of political community, and institutional form of democracy. There is also coherence in the literature about the main problems with each approach. However, it is clear that key authors within each approach have their own detailed accounts that differ in some respects from others that share their broad vision. Recognizing these differences, this typology aims to identify and organize broad responses to globalization, not to simplify or ignore key political positions within or beyond these accounts. Indeed, while each approach possesses a high degree of coherence around a distinct normative vision, the differences within these approaches are often just as important as the differences between them, especially with regard to programs for implementing their particular visions in practice. For instance, transnational deliberative democrats agree that the deliberative capacities of those agents involved in global politics must be enhanced, but disagree about whether meaningful deliberation must utilize formal institutions or rely on the more freeform interactions of transnational civil society. Also, social democrats agree upon a vision of equality, but disagree on whether this must be realized by reforming capitalism or through a revolution which supplants capitalism.

Table 1: Global Democratic Theory

Despite the diversity of responses in global democratic theory, there are some general points of agreement about the impact of globalization and global governance on the prospects of democracy. First, in addition to the widespread rejection of world government, there is general agreement about the limits of liberal representative democracy located within the nation-state under conditions of globalization. While cosmopolitan democracy gives the most direct and detailed account of the eroding capacities of citizens to exercise public rule through the state, deliberative approaches also emphasize the failure of the state to create inclusive forms of dialogue and deliberation that can meaningfully address global problems. Indeed, even liberal internationalists who are comfortable locating democracy within the nation-state contend that global governance arrangements need to develop enhanced forms of accountability to ensure they do not extinguish national democracy. Likewise, social democrats ground their normative claims in a reformist or revolutionary role for democratic states, but also put considerable emphasis on the role of international workers movements in regulating the global economy. More radically, Hardt and Negri argue that liberal democracy is oppressive because it is corrupted by state sovereignty and the imperatives of capitalism. The common theme here is that democracy must to some extent be extended beyond the nation-state in order realize or protect the democratic freedoms of citizens in an age of globalization.

Second, there is also a prominent theme in the literature that suggests democracy must not only be globalized, but also to some extent socialized. This is most clearly evident in the social democratic and radical approaches that seek to reform or overturn capitalism in order to create democratic communities that are responsive to human needs rather than financial markets. But it is also evident in the deliberative approach that argues for subjecting economic discourses and practices, such as those associated with neoliberalism, to widespread public deliberation that includes a wide range of social and environmental perspectives. Cosmopolitan approaches, and even the liberal approaches, contain advocates for socially oriented policies to ensure democratic rights and capabilities can be realized in a global context. Within the cosmopolitan democracy approach, for example, David Held argues for a catalogue of policies aimed at social justice and social solidarity to establish the conditions for effective participation and a fair and equal electoral system. While liberal internationalists are much more restrained in this regard, some scholars such as Daniel Deudney and John G. Ikenberry call for a return to the social underpinnings of liberal internationalism to restore the balance between capitalism and socioeconomic equity within the democratic world. This would enable an effective and attractive international community of democracies to counter the existing authoritarian states. What all these perspectives share is the idea that some attention must be paid to establishing social conditions that make democracy meaningful, effective and attractive to citizens all over the world.

Finally, there is also widespread agreement about the importance of civil society in creating more transparent and accountable global governance. Apart from the radical approach of Hardt and Negri, transparency and accountability figure prominently in the normative frameworks and programs for change in global democratic theory. Indeed, all approaches agree that technocratic effectiveness is not the only or best standard by which to judge global governance, nor is it any more important than democratic criteria and mechanisms of public oversight. In this regard, the inclusion of civil society actors is a central element of enhancing the transparency and accountability of global governance because they can play important roles in channelling up the knowledge and concerns of citizens, while also monitoring the activities of global governance for citizens that are distant or excluded from its decision-making processes. While the deliberative and radical approaches place central importance on civil society or the multitude cooperating outside of state control, cosmopolitan democrats and social democrats also ground their arguments in some form of transnational social activity. Furthermore, despite its ambivalence to civil society, the liberal internationalist approach does acknowledge the growing existence of transnational actors and their contribution to pluralizing world politics, even though it sees only minimal potential for it to enhance the accountability of global governance.

These areas of agreement provide only a broad outline of the main concerns of global democratic theory. Perhaps more significant in terms of mapping the literature and developing concrete democratic responses to globalization are the areas of disagreement. The global democratic theory literature clearly contains wide differences not only with regard to the central vision that each approach attempts to realize, but also in relation to the kinds of institutions that could feasibly be developed. These differences are reflected in various design choices that are explained in the next section. While the argument of cosmopolitan democracy and its advocacy of a global legal and electoral system in the 1990s was in many respects the origin of global democratic theory, many scholars have since based their approach on an explicit rejection of a global system of law and democracy, often in direct critique of the cosmopolitan democracy scholarship. Liberal internationalism and social democracy ground democracy primarily in the nation-state without seeing the need for cosmopolitan democratic institutions, and transnational deliberative democracy and radical democracy contend that the global architecture of cosmopolitan democracy is unfeasible, undesirable and unnecessary because they seek a form of democracy that rests upon non-electoral avenues of democratic practice.

These debates with cosmopolitan democracy reveal widespread disagreement within global democratic theory concerning the desirable location of political community. Liberal internationalists and social democrats still see political community as a primarily national affair, while cosmopolitan democracy, deliberative democracy and radical democracy see global and transnational political communities emerging and thus democracy beyond the state as being both possible and necessary. They also highlight another general point of difference concerning the form of democracy itself. In many cases, scholars are arguing for a form of democracy that is dramatically different from liberal representative democracy and its focus on elections, law and authorized representatives bound to a specific territory. For example, transnational deliberative democracy, social democracy and radical democracy explicitly seek to transcend liberal approaches and attempt to develop more inclusive forms of democratic practice that are broader ranging in scope and underpinned by social justice.

The value of global democratic theory lies in its articulation of a range of approaches that can help citizens to make sense of the changes underway as a result of globalization and critically rethink the democratic organization of national and global governance. The purpose of this book has been to present these approaches as a common body of theory in order to outline the diverse range of views, but also to encourage consideration of the approaches in relation to each other so that a productive dialogue can be established between them in order to advance scholarly debates and foster further refinement of the theories. More importantly, however, it is hoped that presenting the approaches in this way can be useful in informing practical action by citizens by allowing them to recognize common ground, consider the reasons for their different political choices, and crucially, widen political imaginations about how democracy might operate in the future to improve the organization of global governance.

Global Democratic Futures

Clearly, national and global governance have undergone significant changes due to the impact of globalization and neo-liberal reforms in recent decades. While it is the case that the liberalization and privatization agenda of neo-liberalism has restricted representative democracy in many ways, public pressure has also resulted in increasing forms of citizen engagement with governance apparatuses. Many global governance bodies like the WTO, World Bank and G20 have since the mid-1990s increased their public engagement and outreach to buttress their legitimacy (Esty 2002; O’Brien et al. 2000; Scholte 2011b). Furthermore, the recent development of transnational networks of governance in specific policy domains ranging from banking supervision to environmental compliance involve greater participation with key public stakeholders, even if there is less general oversight from elected representatives (Hale and Held 2011: 29). In many cases, NGOs and social movements have demanded access and succeeded in gaining participation in various fora of national and global policy-making. These trends have shifted decision-making authority away from governments that at least nominally represent societies as a whole, to technocrats and non-official actors with more specific interests and questionable representative credentials. This has led to renewed interest in the kinds of individuals, movements and organizations that will be the prime drivers of democratization along transnational or cosmopolitan lines (Archibugi and Held 2011; Archibugi, et al. 2012; Bray 2011; Scholte 2011b). The scholarship of global democratic theory contributes to our understanding of the problems and possibilities for democracy in this context. It provides the theoretical frameworks to analyze and support the democratic potential of these developments and thus contributes to efforts to rethink and redesign democracy on a global scale.

The capacity of global democratic theory to rethink democracy is evident in its wide-ranging ethical visions. In this regard, the first step in reconsidering the future of democracy is to destabilize the notion that elected representation within the nation-state is the only way to conceive of democratic life. Presenting electorally representative states as merely one interpretation of democracy among a range of alternatives opens up the political imaginary of citizens and widens the basis for democratic innovations. While there is little doubt that liberal representative democracy has fostered major positive advances in the development of public rule, global democratic theory scholarship also raises serious questions about its future given the impact of globalization and growing significance of global governance. Specifically, it contains profound criticisms of the existing liberal model and the way it privileges powerful domestic interests at the expense of others, particularly the interests of people living outside the nation-state who are nevertheless affected by the decisions made by those living within it. Concerns about excluded outsiders explains the prominence of the all-affected principle as a guide to extending democracy beyond the territory of any one state, either as a global constitutional principle defining political communities (cosmopolitan democracy), an ideal that frames deliberation across national borders (deliberative democracy), or a supplementary benchmark that shapes mechanisms of accountability within government networks (liberal internationalism). Furthermore, concerns that policy-making in many liberal states is heavily influenced by wealthy citizens and the interests of capitalists has led to alternative deliberative, social democratic and radical visions of political economy which include democratizing the global economy. This kind of thinking provides a stark contrast to dominant conceptions of democracy linked to political liberalism and a capitalist economy. As such, global democratic theory as a whole seeks to defend the democratic freedoms of citizens by avoiding oligarchy and world government, but also provides alternatives to the dominant liberal approaches to these issues.

In addition to opening up democratic futures, global democratic theory also provides specific political alternatives that reflect a number of key design choices. The first major design choice relates to the institutionalization of democracy. A major fault line in global democratic theory exists between “top-down” constitutional perspectives on democracy, which advocate the creation of formal democratic structures with electoral and judicial components, and “bottom-up” discursive perspectives on democracy, which advocate the cultivation of public cooperation and deliberation in a common “lifeworld” detached from formal institutions in national or transnational settings. Constitutional perspectives are evident in the approaches of liberal internationalism, cosmopolitan democracy and social democracy, while discursive approaches are articulated within deliberative and radical democracy. However, while the emphasis is usually placed on one or the other, most scholars do not exclusively focus on either constitutional design or generating informal publics. For example, some scholars in the deliberative democracy tradition explore ways to formally institutionalize deliberative theory (Dryzek and Niemeyer 2008), or base the solidarity of democratic publics on “constitutional patriotism” (Habermas 1999). More broadly, in order to ensure deliberation has a consequential effect on formal decision-making, deliberative democrats need to consider how to change existing constitutional rules that privilege the aggregation of votes. Conversely, constitutional accounts such as cosmopolitan democracy rely upon communication and deliberation in civil society to inform representative processes and must consider the social and cultural conditions required for the ongoing support of constitutional rules. Generally speaking, the question of whether democracy requires formal constitutionalism looms as an important question in establishing the nature and feasibility of democracy beyond the nation-state.

Another contentious issue concerning institutionalization is the role of the state in democratic politics (see also Chapter 1). While the approaches of cosmopolitan, transnational deliberative and radical democratic theory wish to downgrade or abolish the connection between democracy and the state, liberal internationalism, social democracy and republican elements of deliberative theory place considerable importance on the state’s role in institutionalizing democratic politics. Deliberative and radical accounts of global democratic theory are evident in the activity of protest movements like the Occupy Movement, which point to the participatory political spaces that can be created offering variegated forms of politics that stand in opposition to prevailing patterns of dominance and power. However, most scholars in global democratic theory recognize that the state will continue to be an important component of governance, despite the rising importance of global governance and transnational civil society. This means that how each of the approaches reconciles their account of democracy to the ongoing presence of the state remains an important ongoing question. At worst, states can act to significantly undermine transnational forms of activism and democracy. Even in a more positive sense, there are still important questions to be answered about how transnational forms of activism and democratic practice can productively interface with the state and citizens. As such, the work of deliberative and republican theory concerning the dual role of citizens acting politically within their state and within transnational civil society appears to be an important line of inquiry. It is important because the global constitutionalism of cosmopolitan democracy appears to be an unlikely prospect in the near future and state constitutionalism alone is insufficient to deal with the growing number of global problems. In order to develop a substantial account of how to respond to globalization, more consideration needs to be given to how people can act as democratic citizens in both domestic and transnational contexts in the absence of a densely constitutionalized global system.

A second key design choice refers to the scope of public issues subject to democratic control. Clearly, liberal democrats are comfortable with a limited account of democratic scope to avoid the tyranny of the majority and preserve natural freedoms by creating an inviolable private sphere outside of political control. These limits are clearly demonstrated in the governance of economic issues where there is a strong commitment to recognizing the importance of private property rights and delegating decision-making processes to markets, technocratic officials, and central bankers. The contemporary strength of these limits is demonstrated by the compromised efforts of the Third Way to depart from neo-liberal orthodoxy. Most positions in global democratic theory contest the neo-liberal “hands off” approach to the global economy, but vary in the extent to which they want to regulate capitalism in order to realize democracy. While liberal internationalists and cosmopolitans wish to retain capitalism, to varying degrees they argue that enhancing the governance of global markets is necessary to provide public goods and stabilize economic activity. The other approaches argue for much greater democratic control. Social democratic, deliberative and radical accounts develop broader accounts of the scope of democracy, especially with regards to how democratic activity should inform economic policy-making. These approaches have accounts of democracy that make economic issues a central facet of public deliberation and determination, rather than leaving economic decisions to technocrats and markets that are insulated from democracy. Again, scholars within these approaches differ with regard to how far democracy should control economic life. Some social democrats want to reform capitalism and redistribute resources, while other social and radical democrats and express vehement opposition to capitalism and wish to see democratic planning of economic activity in order to realize equality. The recent crises in global capitalism have generated renewed debates over the level of public control over economic policy-making and this has renewed interest in social democratic, participatory and radical traditions of thought, as evident in the recent development of protest movements in the US and Europe (Isakhan and Slaughter 2014; Scholte 2011b, 2014).

A third key design choice relates to the scale and nature of political community. In terms of scale, while liberalism accepts human rights as a universal principle, these rights tend to be interpreted as moral values that need to be embedded in national politics, rather than as political ideals involving questions of citizenship, loyalty and collective political agency that would grant political rights to outsiders. As such, liberal internationalists do not conceive of a political community of citizens beyond the nation-state. All of the other approaches of global democratic theory, in contrast, do have an account of political community that exists beyond or across national boundaries, whether this is based on the all-affected principle, existing channels of communication, or immaterial production. However, these various accounts of political community envision different possibilities concerning the relationship between the individual and the collective, as well as different ways of dealing with questions of difference and internal dissent. Deliberative, social democratic and radical approaches conceive of communities based on consensus among citizens and have a high tolerance for dissent, but it must also be noted that social democracy assumes a community committed to moderating capitalism, and deliberative and radical accounts assume meta-agreement among citizens about the value of inclusion and wide-ranging participation in common activities. While further research is certainly needed to examine to what extent these political visions are emerging in contemporary social movements, the key issue is that the nature of political community and questions of identity and political loyalty are being challenged by globalization. Global democratic theory offers differing accounts of how existing forms of political community could be transformed from prevailing conceptions of nationalism.

Underlying these design choices is the issue of how citizens ought to use the approaches of global democratic theory. While many proposals have the character of plans or institutional blueprints, it is also important to see them as approaches that can be applied more pragmatically and selectively. Some approaches, such as cosmopolitan democracy, are fairly complete in their vision, but other approaches could be applied in part and selectively combined with others. For example, liberal internationalist proposals for enhancing the accountability and transparency of global governance could be combined with elements of deliberative and social democracy directed at improving the deliberative and representative credentials of its institutions, particularly in economic areas. Outside of formal institutions of the state, there are examples of practical social democratic efforts to develop collectives and other forms of democratic wealth ownership (Guinan 2013), and other forms of grass roots participation underpinned by deliberative and radical theories of democracy. Indeed, there are signs that we are entering a new phase of public participation in global governance, but this phase has the character of incremental and piecemeal democratizing shifts rather than wholesale changes in global governance. This suggests that a pragmatic approach to global democratic theory is warranted that avoids purely top-down approaches centred on elite-led constitutional change prominent in liberal internationalist and cosmopolitan theories, or purely bottom-up approaches centred on the deliberative and oppositional capacities of civil society and social movements prominent in the deliberative and radical approaches. This pragmatic approach suggests that the best prospects for global or transnational democracy emerge when broad coalitions involving states, international organizations and NGOs use their combined political and moral power to democratize a specifically problematic issue or institution. As such, the approaches covered in this book can help to identify common ground that could develop mutually beneficial coalitions. Further engagement and dialogue between the approaches would help to refine arguments and proposals that could be used on the ground. In helping to build these coalitions, the approaches analyzed in this book can be important reference points and serve as practical guidelines for citizens and leaders to create a more democratic world.

Conclusion

This book has argued that global democratic theory is a field of scholarship that examines democracy in an age of globalization and consequently makes an important contribution to understanding and guiding democratic politics in a complex and challenging global context. In an era where democracy is more widespread but also more constrained by the displacement of decision-making to global governance and global markets, it is important to think critically about the future of liberal democracy located within the nation-state and widen our political imaginations to include alternative forms of democratic practice and new ways of designing democracy. From this angle, it is also important to consider the limits and future of global democratic theory itself. Clearly, other areas of scholarship such as the global governance and global political economy literature are important complements to global democratic theory in understanding the changes underway in the contemporary world. While global democratic theory focuses upon the disjuncture between the state-based democracy and the globalization of politics, other disciplines also offer crucial insights into the changing context of global politics. Moreover, it is necessary to point out that global democratic theory originated as a predominantly Western discourse, which will increasingly have to engage with non-Western political theories and political practice in the future as the fates of communities all over the world become more globally intertwined.

Finally, it is important to reflect on the untenable nature of our current circumstances. Despite the globalization of economic, social, political, and cultural relations, and despite the fact that democracy has become the main legitimating principle of political rule, democracy is still confined to the domestic spheres of some nation-states. In this context, there are important questions to be answered about how people can meaningfully participate in the full range of governance institutions that shape their daily lives. In recent decades, the shortcomings of national democracy in dealing with global problems such as climate change and financial crises, as well as recognition of the “democratic deficits” of existing global governance, have generated a range of social movements and forms of activism that seek to shape the agenda of global decision-making and attempt to express public views that go beyond state interests. As such, it is important to remember that we are at the “beginning” of considering transnational democracy rather than at the end (Goodin 2010) and the reflections of democratic theory can assist leaders and citizens in understanding the impact of globalization on democracy and the problems and possibilities of new forms of democratic politics on a global scale. Global democratic theory can contribute to developing the political knowledge required by citizens to respond to the impact of globalization on the democratic state as well as help them to identify the democratic opportunities in global governance and transnational civil society. Global democratic theory thus offers a wide array of insights concerning how to rethink and redesign democracy in an increasingly globalized world.

Key Readings

Archibugi, D. and Held, D. (2011) Cosmopolitan democracy: paths and agents. Ethics and International Affairs, 25 (4), 433–61.

Archibugi, D., Koenig-Archibugi, M. and Marchetti, R. (2012) Global Democracy: Normative and Empirical Perspectives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Goodin, R. (2010) Global democracy: in the beginning. International Theory 2 (2), 175–209.

Scholte, J. A. (2014) Reinventing global democracy. European Journal of International Relations, 20 (1), 3–28.

Scholte J. A. (ed.) (2011) Building Global Democracy? Civil Society and Accountable Global Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.