If the bigger picture is considered, this will not be merely a case study of inadequate corporate social responsibility – a black sheep in the otherwise supposedly exemplary mining industry – but an incident that unveils many relationships that would otherwise be pushed into the background. Without addressing the larger connections between Lonmin and the metabolism of profit, leading to two major German firms – BASF and Volkswagen – and at least one agency of international neoliberal power, the World Bank, even a partial fix for the problems at Marikana is unlikely, as unfortunately has been proven to be the case.

It is tempting to begin with the highest-profile individual – Cyril Ramaphosa – who still receives blame for the massacre. Incriminating email evidence shows that the day before, as the main local owner of Lonmin, Ramaphosa repeatedly insisted that the police move in for ‘concomitant action’ against ‘dastardly criminals’ who were engaged in a wildcat strike. Only around five years later did Ramaphosa apologise for the choice of words in his email. He certainly would not have wanted a massacre, as subsequently unfolded a day later. Yet testimony by police underlings to the Farlam Commission indicates in no uncertain terms that as they surrounded the mineworkers in Marikana gathering on the hill the day after Ramaphosa’s emails, they interpreted their duty as, suddenly, lethal.

In his book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Walter Rodney (1973) used a British multinational corporation (Unilever) to draw the links between North and South. As Rodney explained:

The question as to who and what is responsible for African underdevelopment can be answered at two levels. Firstly, the answer is that the operation of the imperialist system bears major responsibility for African economic retardation by draining African wealth and by making it impossible to develop more rapidly the resources of the continent. Secondly, one has to deal with those who manipulate the system and those who are either agents or unwitting accomplices of the said system.

But in the subsequent five years, as Ramaphosa rose to the presidency of South Africa in February 2018, a useful myth circulated. Among others (e.g. Everatt, 2018), New York Times journalist Norimitsu Onishi (2018) claimed, ‘Ramaphosa was accused of using his political influence to press for a police crackdown, though an official inquiry into the massacre eventually absolved him of guilt.’ And to be sure, Justice Farlam and his commission (2015:438) indeed concluded, ‘There is no basis for the Commission to find even on a prima facie basis that Mr Ramaphosa is guilty of the crimes he is alleged to have committed.’

The inability to consider structural processes and corporate privileges – including those ‘critical to the operation of the imperialist system’, as Rodney put it – behind the Marikana massacre led to some important silences in the Farlam Commission.

Thus, on the one hand, the Farlam Commission could not avoid consideration of the obvious misery that characterised Marikana mineworkers’ daily lives. Lonmin ‘created an environment which was conducive to the creation of tension, labour unrest, disunity among its employees’ (Farlam, 2015:522). It repeated this finding twice more, stressing how Lonmin ‘created an environment conducive to the creation of tension and labour unrest by failing to comply with the housing obligations’ it was legally committed to within the firm’s social and labour plans (SLPs), which were required by the state for it to gain mining rights to South Africa’s platinum (Farlam, 2015:557). Lonmin’s SLP commitment called for 5,500 houses to be built between 2007 and 2011, at a cost of R665 million (US$106 million at peak rand value in mid-2011, but far less when the rand declined, e.g. to the value of just $37 million at the very lowest point in early 2016). But by the time of the Marikana massacre, Lonmin had only built three show houses and even they were uninhabitable. Lonmin repeatedly violated its SLP even though it openly acknowledged in risk assessments that one result of not building houses could be ‘withdrawal of our Mining Licences resulting from failure to deliver commitments made’ (Farlam Commission, 2015:534). Drawing out the irresponsibility of Lonmin was one of the merits of the Farlam Commission.

On the other hand, the commission report had telling silences, for it did not even mention the Lonmin board’s Transformation Committee, which was responsible for labour and social conditions, including housing. It did not mention that Ramaphosa chaired that committee starting in November 2010, when he could have directed an emergency housing construction programme to make up for lost time. Lonmin’s refusal to build the houses was due to a variety of shifting excuses (Amnesty International, 2016). But the firm’s most important excuse was also Ramaphosa’s own when testifying to the Farlam Commission: a lack of funding within the firm, due to the 2008 world financial meltdown which temporarily reduced demand for platinum. As a 2009 Lonmin report claimed, ‘The financial situation of the company impacted by the global economy on the price of platinum resulted in a review of the housing and hostel upgrade programme’ (Farlam Commission, 2015:534). The rebuttals are simple:

In testifying to Farlam, Ramaphosa did not mention the role of the World Bank, even though it considered its Marikana community development a success story. Hence when it comes to financing, the links from the police massacre of wildcat striking platinum workers up to the highest levels of global capitalism – especially the tax havens and multilateral lenders which transnational corporations regularly access – were specifically obscured by the Farlam Commission. Likewise, as for the consumption of Lonmin’s output, the commission failed to consider a series of upstream purchases of platinum that also deserved consideration. For example, the most important links are to the German firm BASF, which purchased and processed platinum for use by Volkswagen in its diesel engines. Those engines became the source of intense controversy given the firm’s subsequent corporate malfeasance in respect of emission controls.

Before we consider solidarity campaigning, the two cases of linkages from Germany to the Marikana massacre deserve more attention: BASF and, concomitantly, Volkswagen buying Lonmin platinum, and Germany’s role in the World Bank, which committed serious crimes while earning a share of Lonmin’s illegitimate profits. The Bank’s prolific contribution to the super-exploitation of Africa deserves comment in this instance, for even the Bank’s own researchers acknowledge how much the looting of Africa’s minerals by multinational corporations causes its underdevelopment: at least $100 billion annually in natural capital depletion uncompensated by corporate reinvestment (Lange et al., 2018; Bond, 2018). As for Walter Rodney, the story of how ‘Europe underdeveloped Africa’ can be updated because Lonmin (Britain), BASF and Volkswagen are obviously the core firms involved in this case. To be sure, the story of African underdevelopment has subsequently expanded to include firms not only from the North but more recently also from the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa BRICS bloc (Bond and Garcia, 2015). They may well follow in the footsteps of the once-lucrative – now financially and morally bankrupt – German–British arrangements with Lonmin.

Volkswagen’s platinum-demand distortion and Lonmin’s demise

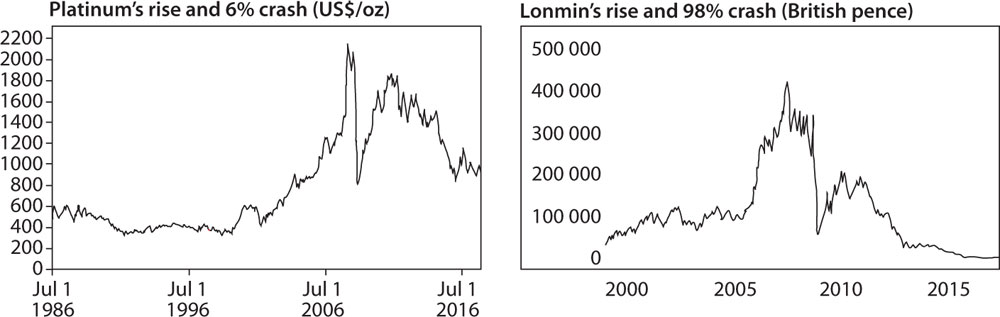

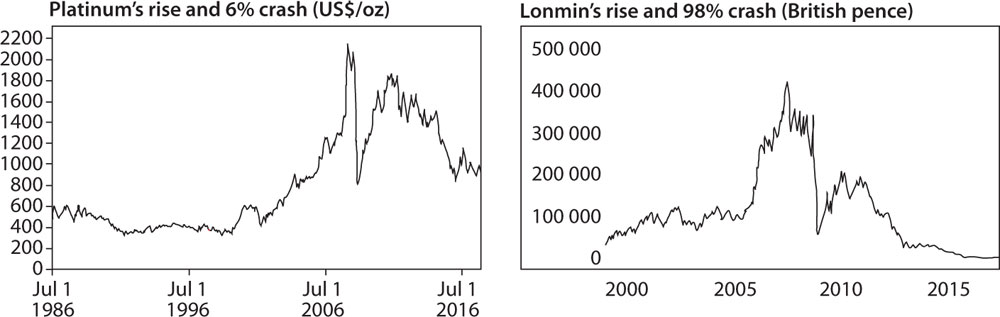

The world capitalist system’s extraordinary capacity to generate crises helps explain the rise and fall of commodity prices, as witnessed in the 2002–11 ‘super-cycle’ rise in the platinum price from $500/ounce to $2,270/ounce in 2007. But after the crash, the price settled at below $1,000 after 2016. The impact of not only the price crashes but Lonmin’s mismanagement was profound, driving the firm’s share value from $28.6 billion in 2007 to $383 million when it was purchased by Sibanye-Stillwater in late 2017.

The price declined during 2015 from $1,500 to $900 and subsequently it remained at the latter low level, at which nearly half of South Africa’s mines were unprofitable. One reason is that Volkswagen was exposed for its abuse of platinum in diesel engines, which were falsely marketed as having lower emissions than they had in reality. The world’s largest car manufacturer was prosecuted and paid more than $15 billion in fines for installing ‘defeat device’ software in diesel-powered vehicles. The scam allowed 40 times the legal limit of nitrogen oxide emissions, a chemical not only dangerous when generating smog (and asthma) but also as a greenhouse gas, 300 times more damaging than carbon dioxide.

One of the world’s leading platinum marketers, Huw Daniel, told Mining Weekly in 2017 that one reason vast oversupply of platinum persisted was that ‘demand took a knock following vehicle manufacturer Volkwagen’s emissions scandal and extensive anti-diesel sentiment, losing market share to palladium’. Of 8.5 million tonnes of demand for platinum in 2016, Daniel noted that 40 per cent was generated in the automotive sector (Solomons, 2017). As the scandal broke, reporter Jo Confino (2015) complained about VW’s broader damage ‘to the corporate sustainability movement’.

Volkswagen’s actions will fuel the cynics who believe businesses are just paying lip service when it comes to issues like climate change and resource scarcity. [...] What the Volkswagen scandal illustrates is that profit maximisation is so deeply embedded in corporate culture that when push comes to shove, the vast majority of companies will put the bottom line above any moral case for change and sometimes even cheat to keep the short-term profits coming in (Confino, 2015).

The bottom line for Lonmin should have included longer-term support for emissions cuts, including platinum fuel cells in new automobiles, buses and other vehicles. As one of the competing mining leaders, Royal Bafokeng Platinum CEO Steve Phiri, put it in late 2017, ‘Our message to particularly the regulators and government is that you cannot produce 80 per cent of the world’s platinum group metals and still be on emission standard euro 2’ (Creamer, 2017). He was referring to the terribly low antipollution standards that the rest of the minerals-energy complex had compelled the state to adopt over the years.

The crash of Lonmin is terribly important because at the time of writing in early 2018, the platinum market remains glutted. The new owner – the Johannesburg firm Sibanye-Stillwater, led by a corporate manager notorious for squeezing margins to improve profits, Neil Froneman – announced when buying Lonmin in December 2017 that it had one overarching objective in acquiring the firm: its relatively cheaper smelting overcapacity for use by other firms. Closure of Lonmin mine shafts will accelerate so as to save more than $100 million annually by 2020. As a result, 38 per cent of Lonmin’s 33,000 employees are due to be retrenched within the next three years, according to Froneman. He also immediately warned critics to cease attacking Lonmin for repeated, ongoing SLP violations: ‘Communities that are unhappy, the Department of Mineral Resources that is unhappy – need to stop and allow us to complete this so that in the longer term we can do more.’

This proved an unconvincing plea, judging by the response of the main trade union leader representing Lonmin workers, Joseph Mathunjwa of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU): ‘We are prepared to join forces with communities around Lonmin to ensure that the interests of mineworkers’ mine-affected communities are defended. We want to warn the new owners and current shareholders that we will fight and not sit quietly as our members’ future is destroyed.’

Banking on Marikana misery

Berlin’s influence at the World Bank is considerable, for as one of five top Bank officials, its ‘Executive Director represents Germany in meetings at the World Bank and engages in direct consultations and negotiations with other Executive Officers in efforts to gain support for the World Bank’s efforts in reducing poverty’, according to the Bank (2017) website. Thanks to its citizens’ generosity since it joined the Bank in 1952, Germany now holds a 4.31 per cent share ownership, ranking it fourth behind the United States (17.17 per cent), Japan (7.39 per cent) and China (4.76 per cent).4 German financing of the Bank, though impossible to calculate, is also lucrative to its numerous bondholders. More importantly, as the strongest European Union economy, Germany has oversized influence in the Bank, with Berlin co-serving with Beijing as global neoliberalism’s most important capital city, now overtaking Trump-ruled Washington DC and Brexit-sabotaged London. Indeed, the power of Germany over the World Bank was revealed when in late 2016, Berlin’s federal development minister Gerd Müller told Bank president Jim Yong Kim to halt any further financing of fossil fuel projects, and within six months Kim then publicly announced this as Bank policy.5

Recent Bank directors have included Ursula Müller (2014–17) and, currently, Claus-Michael Happe and Jürgen Zattler. Even though controversies have been raging for several years about Bank profiteering by Lonmin, none of the German directors has made any recorded statement on the scandal. On rare occasions, the German representative to the Bank takes critical stances against projects, e.g. against Newmont Mining in 2006 following lobbying by Bread for the World (Brot für die Welt).

In 2015, the Farlam Commission’s failure to fully connect the dots was reflected in how explicitly its leaders and researchers ignored the glaring role of the World Bank. At the same time that Lonmin workers were meant to live in housing that was not even of 19th-century quality, the firm was removing R1.3 billion ($148 million) to Bermuda from 2007 to 2011, ostensibly for marketing expenses (Forslund, 2015). In addition, from 2007–11 Lonmin paid dividends of more than $600 million while ignoring ‘its much lesser R655 million legally binding commitments to build social housing for its workers’ (Higginbottom, 2017:17). One beneficiary of these profit and dividend outflows was the Bank’s private-sector investment arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

From 2007, the IFC had invested $15 million in an equity position in Lonmin, via the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, to support ‘the development of a comprehensive, large-scale community and local economic development program’.6 This stake, along with another $35 million share purchased subsequently, brought with it the IFC’s Investment and Advisory (I&A) services, which was meant to support Lonmin’s community development strategies. In addition to the $50 million equity investment, World Bank president Robert Zoellick authorised a further loan facility of $100 million, although Lonmin never drew this down. As the well-read business journalist Rob Rose (2007) reported at the time in one of the country’s main newspapers:

Lonmin CEO Brad Mills said the plan was to use the [$100 million] cash to create ‘thriving communities’ around Lonmin’s projects so that when the platinum was depleted and the miners left, the communities would be ‘comfortably middle-class’ and able to support themselves. ‘We intend to use 100 per cent of this facility to facilitate partners in our business,’ Mills said. Lonmin would use part of the cash to build 5,000 houses in the next five years for community members, with 600 scheduled to be built this year.7

From Washington, meanwhile, the IFC regularly bragged about Lonmin’s ‘developmental success’ thanks to the introduction of IFC ‘best case’ practices, ranging from economic development to racially progressive procurement and community involvement to gender work relations (IFC, 2006, 2010).8

Feminist activist Samantha Hargreaves (2013) highlights the general imbalance of power between women and men and reaches back into the migrant labour system itself: ‘The Marikana story is about much more than a strike for higher wages, it is also a story about a crisis in social reproduction. State neglect and corporate greed have fomented household crises stretching from the mines back to the sources of migrant labour in far-flung regions and neighbours’.

The Bank was especially delighted with Lonmin’s ‘gender equity’ work (Burger and Sepora, 2009). Moreover, according to its own 2012 Sustainable Development Report, Lonmin has established community resettlement policies which comply with the World Bank Operation Directives on Resettlement of Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Property. There were no resettlements of communities and no grievances lodged relating to resettlements. In terms of the Restitution of Land Rights Act 22 of 1994, the company is in the process of addressing several land claims lodged against it before 2011. The resolution of these claims is being managed within the legislative framework of the regional Land Claims Commission and Land Claims Court (Lonmin, 2012).

Mismanagement at Lonmin’s Marikana operation was endemic, in spite of IFC marketing propaganda. The church-founded Bench Marks Foundation reported in 2007 (just as the IFC was getting involved) and 2012 (after the main IFC work had been completed) about the ways Lonmin had demonstrably failed in the main areas of corporate social responsibility: job creation and subcontracting (including labour broking); migrant labour, living conditions and the living-out allowance; ineffectual community social investments and lack of meaningful community engagement and participation; and environmental discharges and irresponsible water use, especially in relation to local farming (Bench Marks Foundation, 2007).

The Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) (2012) argued that the World Bank had ignored critical information before making its Lonmin investments:

Despite attesting to a close working relationship with the South African police force on matters of security, a statement made yesterday [16 August 2012] by Lonmin chairman Roger Phillimore characterised the violence as ‘clearly a public order rather than a labour relations associated matter’. [...] In addition to seeking a full investigation into the violence and what led to it, CIEL has called on World Bank President, Jim Yong Kim, to revisit the Bank’s investment in this project in light of recent events, specifically, and its approach to lending in the extractive industries more generally.

Exactly two weeks after the massacre, Kim went to nearby Pretoria and Johannesburg for a visit. Tellingly, he neglected to check on his Lonmin investment in Marikana and instead gave a high-profile endorsement to an IFC deal with a small junk-mail firm (Mailtronic Direct Marketing) that was prospering from state tenders. The other systems of accountability within the Bank were also deficient, as women residents of Marikana would later find. From 2012 to 2013, an investigation by the IFC’s independent Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) took place, in which the CAO (2013) objected to the IFC’s evaluation of ‘industrial relations and worker security’ problems that were apparent over at least 18 months before the August killings. The CAO found the IFC had inadequate monitoring systems at several crucial points:

However, in the absence of a formal complaint from workers, the CAO dubiously argued that no link could be established between these concerns and the deaths at Marikana, and closed the case in 2014. As Alide Dasnois (2014) remarked:

Neither the IFC evaluation teams nor the World Bank’s own evaluation team, which reported in June 2012, had much to say about employment issues at Lonmin in the run-up to the events in August. After the killings, the IFC team ‘noted violence at Lonmin occurring in the context of increasing tensions between rival unions in the mining sector in South Africa, mines being shut down, worker layoffs and declining workers’ bonuses’.

‘Stakeholders’ emerge from the shacks to attack the Bank

As a result, furious women residents of the Nkaneng shack settlement formed a group, Sikhala Sonke (‘We cry together’, later the subject of a major film, Strike a Rock), aided by leading Johannesburg-based public interest lawyers at the Wits University Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS) (Marinovich, 2015). In 2015, they placed a complaint against the IFC with the CAO (CALS, 2017:1), citing:

[...] an absence of roads, sanitation and proper housing, as well as accessible, potable, and reliable sources of water. Further, the Complainants allege that to the extent the mine offers benefits in the form of employment, less than 8 per cent of employees currently are women. The complainants also allege environmental pollution, specifically relating to air and water. They further allege failure by Lonmin to provide the Nkaneng community with adequate health and educational facilities which were promised at the inception of the project.

Indeed, there were persistent problems with men forcing women mineworkers into unwanted underground sexual relations, and Lonmin was no better than other mining houses in spite of the IFC intervention, according to research by Asanda Benya (2009, 2015). Instead of monitoring community development and gender equity directly, ‘the IFC has played the role of an “absentee landlord”, relying on the annual reports of the company. The IFC should have been more vigilant around their investment, but at least they have a mechanism to receive complaints,’ according to CALS director Bonita Meyerfield (Davis, 2015). The Sikhala Sonke complaint (CALS, 2015: 17) pointed out that even a year before it invested in Lonmin, the IFC itself held a high-minded, self-congratulatory stance on development finance ‘performance standards’. IFC statements about gender equity at Marikana have focused upon the rising (albeit still small) share of women in the workplace. IFC mining principal investment officer Robin Weisman claimed Lonmin as a success story in 2017, simply ignoring local women’s critiques.

Lonmin’s 2008 Sustainability Report noted a substantial decrease in community support. The 2009 and 2010 Sustainability Reports contained no data on community support, likely because it was in free fall. Then in Lonmin’s 2011 report, received by the IFC, a ‘principal risk’ identified within Lonmin’s staff and community stakeholder engagement was that ‘poor community and employee relations’ could result in ‘strike action and civil unrest’. In the light of all this information, the IFC ought to have been aware of the significant deterioration of mine-community relations. The IFC ought to have been aware that Lonmin was failing to provide adequate housing, water and sanitation to the local communities and ought to have known that Lonmin was failing to reach its targets for gender mainstreaming in the mine. Even the most basic review would have identified the very serious, detrimental impact of the mine on the local community and the failure of the I&A Project to deliver the benefits it promised.

As for Sikhala Sonke’s demands, they were posed in reasonable terms, within the confines of what an international investor in Lonmin should be expected to do, bounded by the constraints of CSR: ‘Consequently they urge the CAO to conduct a Compliance Investigation irrespective of the outcome of any Dispute Resolution process’ (CALS, 2015:25). That process was adopted with strong endorsement from the CAO, but during 2016 – after three meetings – it broke down:

In March 2017 the Complainants informed CAO that they were withdrawing from the dialogue process, citing, from their perspective, the lack of progress and failed implementation of undertakings given by Lonmin as part of the dialogue. The Complainants are of the view that none of their grievances have been resolved. Accordingly, the complaint will be transferred to CAO Compliance (CAO, 2017:2).

In all of this oversight, perhaps most important was what did not appear on the agenda: the broader nature of the World Bank’s role in financing the underdevelopment of Marikana. Such an agenda would bear in mind the Bank’s prolific support for apartheid, its role in introducing and cementing neoliberalism in public policy between 1990 and 1996, its other dubious IFC investments in the post-apartheid economy (including the highly profitable Net1 CPS extraction of funds from the poorest social grant recipients), its largest-ever loan ($3.75 billion) given for the corruption-riddled Medupi power plant, its bizarre research on inequality and various other features of Bank advocacy and investment (Bond, 2014).

Campaigning for justice at Marikana

The struggles for fair wages by AMCU workers and decent living conditions by Sikhala Sonke women activists have been joined by solidarity campaigns, of which the Plough Back the Fruits campaign is exemplary. The Plough Back the Fruits movement consists of the German branches of the Association of Ethical Shareholders, Bread for the World, the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, KASA (Ecumenical Services on Southern Africa), the Swiss-based KEESA (Swiss Apartheid Debt and Reparations Campaign) and SOLIFONDS. From South Africa, the participants are Bench Marks Foundation, Khulumani Support Group and Widows of Marikana.

BASF resists acknowledging this secondary pressure but in 2017 was finally compelled to admit, ‘We note that the development of living conditions for Lonmin workers is not progressing as quickly as one would expect or hope. This is due to the fact that the situation in South Africa is extremely multi-faced and cannot be solved in the short term by one institution alone’ (Faku, 2017). Indeed, it must be observed that solutions to these problems have not been found in disparate civil society strategies that followed the Marikana massacre. One strategy was the demand for higher wages, which the workers are gradually winning, though the R12 500/month (in 2017 just $925/month) requested will only be achieved in 2019 when inflation will have eroded that sum by more than a third. Another strategy was community development, advocated most strongly by Sikhala Sonke women who, in part, attacked the World Bank for its failures, followed by further Bapo community grievances.

In future months and years, can these forces – women, mineworkers, the Bapo people, environmentalists – find common cause? As Hargreaves (2013) insists, ‘Narrow male-dominated trade union and worker interests mean that hope for a radical resolution lies in the struggles of women in places like Wonderkop. The challenge is linking these with (mainly male) worker struggles and environmentalist solidarity to challenge the extractivist model of development, the social, economic and environmental costs of which are principally borne by working-class and peasant women.’

It may well be, in this context, that both shop-floor and grassroots forces require assistance from institutions with larger agendas, including those challenging the broader economic agenda of transnational corporations. For example, in mid-2015 Lonmin’s tax avoidance was raised by AIDC director Brian Ashley (a leading AMCU adviser): ‘As the AIDC, we will pursue a campaign for the company’s licence to be revoked and for the state owned mining company to take over the company. [...] We need to hold these huge corporations to account. You cannot have a company in a country that needs to be rebuilt sucking the resources dry’ (Faku, 2015b).

At the same time, the leftist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party also demanded mine nationalisation and, in the case of the massacre, punishment, including both jail for Lonmin leaders and compensation: ‘The EFF will institute a process of reparations against Lonmin to demand reparations and payments of all the families of deceased mineworkers of R10 million ($1.1 million) per family and R5 million ($0.55 million) per injured worker’ (Faku, 2015a, 2015b). Even the centre-right Democratic Alliance announced that it also supported forcing Lonmin to compensate massacre victims’ families. These are the sorts of demands that should be put to Sibanye-Stillwater.

With Lonmin unable to continue as a growing concern, much bigger questions about political strategy can be raised. To think creatively about the options for Lonmin (via Sibanye-Stillwater) not only requires a revived debate about whether or not to take away the firm’s mining licence (as AIDC advocates and as was threatened by the South African government in late 2016) or to nationalise it with – or preferably without (given such immense liabilities) – compensation to traditional overseas owners (as the EFF argues).

If we put aside the particular problems at Marikana, the disastrous recent period of mining capital’s over-accumulation and ruinous competition also compels much wider considerations of the need for new priorities that would radically change the corporate financing parameters now in place. These might include:

These are the kinds of big-picture strategic questions that can be raised as a result of the injustices that continue at Marikana. For there, we find not the power but also the overlapping, interlocking vulnerabilities associated with Lonmin’s historical abuse of people and the planet (and Sibanye’s likely amplification of these). The vulnerabilities that even huge mining corporations face have so far generated fragmented campaigns for reform. As the limits of reformist strategies are reached in each of these, it is still possible for much greater unity to be established between disparate groups of mining capital’s victims. If these victims soon include investors representing South Africa’s large civil service as well as financiers, it will be up to the grassroots, shop-floor and environmental activists to ensure that an even more exploitative regime of extraction in the platinum belt does not emerge in coming years.

Given the German establishment’s role along the value chain – from supporting the IFC’s private-sector investment regime (no matter how wicked, as in the Lonmin case) to BASF’s and Volkswagen’s roles in the ups and downs of platinum and their failure to conduct minimal oversight – there may be a vital factor that can shift the balance of forces: international solidarity. For just as Germans came to the anti-apartheid movement to heed the call of Tambo, Mandela and the liberation movements, it will not be long before the contradictions in Marikana again demand a unifying support base. Plough Back the Fruits is one model, and it may be that, once made aware of the crimes to which German financing and shareholding are contributing, there will be new opportunities for even more extensive solidarity. For what is being revealed at Marikana about the way platinum is financed, mined, purchased and remoulded within a system of increasingly brutal, ecologically destructive international capitalism should compel Germans of goodwill to examine the full extent of their own responsibilities – as well as their liberatory potential.

1 BASF is the world's largest supplier to the automotive industry.

2 This was the third such public incident involving Ramaphosa’s dubious international financial relations, for as the Paradise Papers revealed in late 2017, Ramaphosa’s firm also retained Mauritius accounts for nefarious purposes. Furthermore, as chair of Africa’s largest cellphone operator, MTN, he suffered continent-wide criticism for illicit capital flight.

3 One standard approach would have been to rent the houses for a nominal maintenance fee, thereby ending Lonmin’s ‘living out allowance’, which in turn could even have allowed the housing to remain a company asset. Thus decent housing for workers would have been supplied, even – as Lonmin complained – if the workers lacked sufficient financial capacity of their own, or if they desired the retention of their rural housing as their main priority because they viewed their Marikana migrant labour commute as temporary and thus not meriting a major residential investment in a desolate site whose lifespan was limited in any case by the wasting platinum asset.

4 Similar voting arrangements prevail at the Bank’s sister institution, the International Monetary Fund, which was led by Horst Köhler from 2000 until he resigned to take up the German presidency in 2004.

5 The Bank’s $3.75 billion loan to Eskom, to finance construction of the fourth-largest coal-fired power plant in the world, remained a source of ongoing embarrassment, even leading to a controversy in early 2018 over Eskom’s inability to repay the Bank. That loan, originally made by the widely discredited Bank president Robert Zoellick in 2010, should be considered odious debt and repudiated by a non-corrupted South African government, once one is finally elected (Bond, 2012).

6 It should be pointed out that in making hard-currency (US dollar) investments in Lonmin during the height of the commodity super-cycle (when at peak in 2011, the South African rand was valued at R6.3 to the US dollar), the World Bank perpetuated its dubious record of compelling repayments in hard currency even though soft currencies like the rand devalued radically after the commodity super-cycle ended in 2011, in the South African rand’s case to as low as R17.9/$ by early 2016, before stabilising in the R12–R14/$ range in subsequent years.

7 The actual numbers should have been 5,500 and 700 if the SLP had been followed to the letter.

8 The IFC was not the only agency to laud Lonmin’s Marikana management. In 2008, the South African commercial bank most actively green-washing its record of minerals and coal investment, Nedbank, awarded Lonmin and the World Bank its top prize in the socio-economic category of the Green Mining Awards (Daily Business News, 2008). By 2010, Lonmin’s Sustainable Development Report was ranked ‘excellent’ by Ernst and Young.

9 See www.aidc.org.za/programmes/million-climate-jobs-campaign/about/.

References

Amnesty International (2016) Smoke and Mirrors: Lonmin’s Failure to Address Housing Conditions at Marikana, Johannesburg, www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr53/4552/2016/en/

Bench Marks Foundation (2007) The Policy Gap: A Review of the Corporate Social Responsibility Programmes of the Platinum Industry in the North West Province, Johannesburg

Bond, P. (2012) Politics of Climate Justice, University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg

Bond, P. (2014) Elite Transition, Pluto Press, London

Bond, P. (2017) In South Africa, Ramaphosa rises as Lonmin expires, Pambazuka, 20 December, www.pambazuka.org/democracy-governance/south-africa-ramaphosa-rises-lonmin-expires

Bond, P. (2018) Economic narratives for resisting extractive industries in Africa, forthcoming in Review of Political Economy

Bond, P. and A. Garcia (eds.) (2015) BRICS: An Anti-Capitalist Critique, Jacana Media, Johannesburg

Burger, A., and B. Sepora (2009) A mine of their own: The women of Lonmin, World Bank, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGENDER/Resources/NewsletterPage6.pdf?cid=PREM_GAPNewsEN_A_E

CALS (Centre for Applied Legal Studies) (2015), Complaint by affected community members in relation to the social and environmental impacts of Lonmin PLC’s operation in Marikana, Complaint to the International Finance Corporation Compliance Advisor Ombudsman, Washington DC, 15 June, www.caoombudsman.org/cases/document-links/documents/ComplaintbyAffectedCommun-itMembersinRelationtoSocialandEnvironmentalImpactsofLonmin20150615.pdf

CALS (Centre for Applied Legal Studies) (2017) Social and labour plans, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, www.wits.ac.za/cals/our-programmes/environmental-justice/social-and-labour-plans/

CIEL (Center for International Environmental Law) (2012) CIEL calls on World Bank to revisit investment in Lonmin, Washington DC, 17 August, https://www.ciel.org/news/ciel-calls-on-world-bank-to-revisit-investment-in-lonmin-operator-of-violence-plagued-south-african-mine/

Confino, J. (2015) After the Volkswagen emissions scandal, why should we trust companies to protect the environment?, Huffington Post, 21 September

Creamer, M. (2017) Introduce stringent anti-emission laws – Royal Bafokeng Platinum, Mining Weekly, 2 August, http://www.miningweekly.com/article/introduce-stringent-anti-emission-laws-royal-bafokeng-platinum-2017-08-02/rep_id:3650

Dasnois, A. (2014) Lonmin investor rapped over the knuckles, GroundUp, 3 December, www.groundup.org.za/article/lonmin-investor-rapped-over-knuckles_2499

Davis, R. (2015) Women of Marikana lodge World Bank complaint against Lonmin, Daily Maverick, 30 June

Everatt, D. (2018) South Africans are trying to decode Ramaphosa (and getting it wrong), The Conversation, 10 January, https://theconversation.com/south-africans-are-trying-to-decode-ramaphosa-and-getting-it-wrong-89886

Faku, D. (2015a) Lonmin repatriated R400m annually, says AIDC report, The Mercury, 3 June

Faku, D. (2015b) Lonmin’s licence is under attack: Share slid 13 percent after report, The Mercury, 6 July

Faku, D. (2017) BASF in ‘threat to walk away from Lonmin’, The Mercury, 3 November, https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/companies/basf-in-threat-to-walk-away-from-lonmin-11832486

Farlam Commission (2015) Marikana Commission of Inquiry: Report on Matters of Public, National and International Concern Arising out of the Tragic Incidents at the Lonmin Mine in Marikana, in the North West Province, Pretoria

Forslund, D. (2015) Briefing on the report ‘Profit shifting, inequality and unaffordability at Lonmin 1999–2012’, Review of African Political Economy 42, 146, pp. 657–665, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03056244.2015.1085217

Hargreaves, S. (2013) More misery in Marikana, Third World Resurgence, https://www.twn.my/title2/resurgence/2013/271-272/cover08.htm

Higginbottom, A. (2017) The Marikana massacre in South Africa, Unpublished paper, London, Kingston University

IFC (International Finance Corporation) (2006) Lonmin: Summary of Proposed Investment, Washington DC, World Bank Group

IFC (International Finance Corporation) (2010) Strategic Community Investment, Washington DC, www.scribd.com/document/96448930/IFC-Handbook-Sustainable-Investments-to-Emerging-Market

International Finance Corporation Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (2013) IFC Investment in Lonmin Platinum Group Metals Project, South Africa, Washington DC, www.cao-ombudsman.org/cases/document-links/documents/CAO_Appraisal_LONMIN_C-I-R4-Y12-F171.pdf

International Finance Corporation Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (2017) Dispute Resolution Conclusion Report – Lonmin-02/Marikana, Washington DC, http://www.cao-ombudsman.org/cases/document-links/documents/Lonmin02DRConclusionReport_May252017.pdf

Lange, G., Q. Wodon and K. Carey (eds.) (2018) The Changing Wealth of Nations 2018, Washington DC, World Bank, doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1046-6

Lonmin (2012) Sustainable Development Report, London

Marinovich, G. (2015) How the women of Marikana are taking on the World Bank, Daily Maverick, 4 July

Onishi, N. (2018) Meet Cyril Ramaphosa, South Africa’s new president and a Mandela favorite, New York Times, 15 February, www.nytimes.com/2018/02/15/world/africa/south-africa-cyril-ramaphosa.html

Rodney, W. (1973) How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications, Llondon

Rose, R. (2007) World Bank body to put $150M into Lonmin,’ Resource Investor, 13 March, www.resourceinvestor.com/2007/03/13/world-bank-body-put-150m-lonmin

Solomons, I. (2017) Platinum industry redoubling marketing efforts in the midst of oversupply, Mining Weekly, 28 July, http://www.miningweekly.com/print-version/platinum-industry-redoubling-efforts-to-promote-the-metals-uses-2017-07-28

World Bank (2017) Voting Powers, www.worldbank.org/en/about/leadership/votingpowers

Proposal for a Transnational Development Plan. Projection onto a company sign of Lonmin in Marikana, 2016.