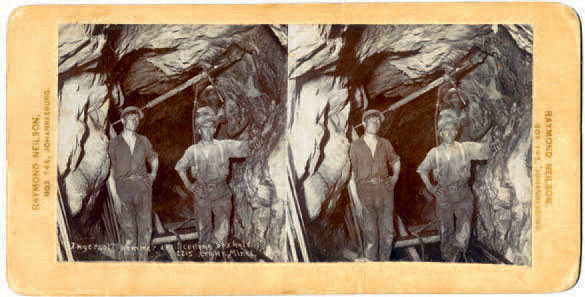

Stereographic image of miners in the Crown mines at the beginning of the 20th century

I pick up the odd wood-and-metal contraption. This is a stereoscope, I am told. It feels old, in the sense that there is a certain worn patina about it and a non-utilitarian elegance to the turned wood and decoration, though not as if it were an expensive piece; just as if it came from an era when there was time for embellishment. It feels cheaply put together, mass-produced and flimsy as opposed to delicate, the engraving detail of the tinny sheet metal rather rough, the fit of the one piece as it glides through the other somewhat rickety in my hands.

I reach for the pile of faded stereographs, flipping through them slowly. There are 24, picked up in an antique shop in an arcade off Cape Town’s Long Street together with the viewing device. A stereograph is composed of two photographs of the same subject taken from slightly different angles. When they are placed in the stereoscope’s wire holder and viewed through the eyeholes, an illusion of perspective and depth is achieved as the two images appear to combine through a trick of parallax.

Susan Sontag remarks that ‘photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy’ (1973:23). And Allan Sekula calls the photograph an ‘incomplete utterance, a message that depends on some external matrix of conditions and presuppositions for its readability. That is, the meaning of any photographic message is necessarily context determined’ (1982:4). In what follows, I will look more closely at two of these 24 pictures and, through a contextual discussion, begin to unpack a few aspects of the complex relationships of photography with its subjects and also with public circulation.

Each thick, oblong card with its rounded, scuffed edges discoloured by age has two seemingly identical images on it, side by side, and is embossed with what I guess must have been the photographer’s or printing studio’s name in gold down the margin: ‘RAYMOND NEILSON, BOX 145, JOHANNESBURG’. The images depict miners underground. Some are very faded, to the extent that the figures in them appear featureless and ghostly. There is virtually no annotation on most of the photos. On just a few of them, spidery white handwriting on the photo itself, as if scratched into the negative before it was printed, announces the name of the machinery or activity in the picture and the name of the mine: ‘Crown Mines’.

I pick up the first card, slot it into the stereoscope and peer through the device. On the left of the two images, the writing announces: ‘Ingersoll hammer drill cutting box hole. C215. Crown Mines.’

I slide the holder backwards and forwards along the wooden shaft to focus. I’m seeing two images, nothing remarkable, until suddenly, at a precise point on the axis, the images coalesce into one which is three-dimensional. The experience is that of a gestalt shift, the optical illusion uncanny. I blink hard. It’s still there. It feels magical, as if the figures in the photos are stepping right out of the card towards me. Their eyes stare into mine through over a century of time, gleaming white out of dirty, sweaty faces. Startlingly tangible, here stand two young white men in a mine shaft, scarcely out of their teens, leaning against rock, each with a hand on the hip and a jauntily cocked hat. They are very young ... yet very old too, I immediately think: definitely dead now and perhaps dead soon after the picture was taken, living at risk, killed in a rockfall or in the First World War. A pang of indefinable emotion hits me. I am amazed at how powerfully this image has flooded my imagination. Even with the difficult viewing process, the effect is astonishing.

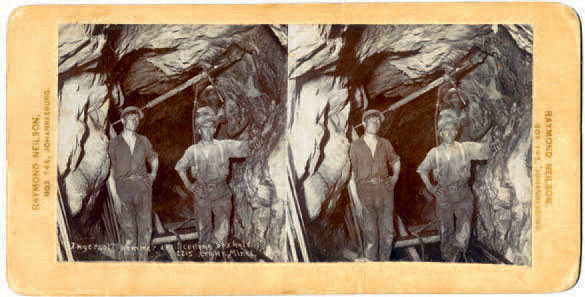

Stereographic image of miners in the Crown mines at the beginning of the 20th century

I am reminded of Sontag’s contention that all photographs are memento mori: ‘To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt’ (1973:11; cf. Berger, 1972 and Barthes, 1981:14).

I also notice that the trick of parallax (and, concurrently, the evocativeness) works most pronouncedly on the figures in the foreground, probably due to the camera angle and vanishing points of the perspective. Behind the two white youngsters, almost fading into the darkness, is a black man, holding up a drill over their heads that seems to penetrate the tunnel of rock in which they are suspended. He appears to have moved during the shot as his face is blurred. This could also be due to the low light in the shaft. Though he is looking straight at me, I can’t connect with him as I do with the figures in front. He is very much in the background, a presence without substance. The way the photo was set up and taken has placed him in that position, and this viewpoint is indelible no matter how hard I try to look past it.

I line up the next image. There is no writing on this one except for what seems to be a reference number: ‘C269’. The figure in the foreground is a black man, miming work with a mallet and chisel against the rock face though clearly standing very still for the shot as he is perfectly in focus, his sceptical gaze directed at us, a sharp shadow thrown on the rock behind him. This is no ordinary lamp light: it seems clear that these pictures have been professionally illumined by the photographer, perhaps using magnesium flares, because the shots definitely predate flash photography.

To the left of the man with the chisel stands a white man, face dark with dirt. He is holding a lamp in one hand and his other grasps a support pile which bisects the shaft and also the photo. Tight-jawed, he stares beyond us, his eyes preoccupied, glazed over. Behind the two men in the foreground, there are more men: parts of two, perhaps three workers can be seen, one a black man crouched down at the rock face behind the man with the chisel.

What strikes me most about this picture – the punctum, after Barthes (1981:27) – is the man with the chisel’s bare feet. He is at work in an extremely hazardous environment without shoes. If one looks at all the photographs, every white worker is wearing boots, but there are several pictures where it is clear that many of the black workers are barefoot. This is shocking visual evidence of an exploitative industry which does not take its workers’ safety seriously, placing these men at incredible risk without the provision of adequate protective attire: none have hard protection for their heads, and the black workers are without shoes. Men not deemed worthy of protection are, by inference, expendable. From these photos, one surmises that black lives are more dispensable than white.

I am curious to find out more about these pictures. Perhaps the visual evidence here is echoed in literature. Or perhaps they can tell us things the literature does not. Who were these people? There is nothing on the back of the photos. No captions, no dates. Who was the photographer? For what purpose were these pictures taken? The lack of answers to these most mundane of questions lends the photos an uncanny, almost spectral quality. I have technical questions about how these pictures were taken, too, such as about the lighting and the camera used. Surely it was large and difficult to manoeuvre down into the mine, and probably an expensive exercise.

With virtually no background information, there is little direct means of understanding how or why these stereographs came into being. I assume that as a viewer now, my experience and interpretation of the images would be informed by a very different paradigm from that inhabited by viewers at the turn of the 20th century. Hence, I attempt to examine the broader historical and theoretical milieu. As John Tagg reminds us, ‘The photograph is not a magical “emanation” but a material product of a material apparatus set to work in specific contexts’ (1988:3).

From the information I have at my disposal, I cannot tell for what exact purpose these photographs were intended. I cannot imagine an overtly business-related use for them, as the annotation is too intermittent: if there were a commercial value to naming the machinery in some of the shots, it would most likely have been named more consistently. If they were to be used for advertising or documentary purposes, this would be of a ‘cabinet of curiosities’ type, in which the spectacle of seeing something usually invisible to the audience would be the main attraction. Perhaps the photos could have had an educational function, although the documentation is too imprecise to serve any real use as an inventory record.

Stereographic image of miners from Johannesburg at the beginning of the 20th century

I google ‘Raymond Neilson’, trying various permutations and keywords in conjunction with the name, with no luck. I google ‘old South African mining photographs’. I find only one promising reference, in a forum post from 30 April 2013 on heritageportal. co.za, a ‘discussion, education and marketing platform serving the South African Heritage Sector’. The post describes a cache of 46 stereographs found with a stereoscope in a cellar in North Yorkshire, England. The writer’s description is strikingly similar to the images I have in hand, right down to her observation of the black workers’ bare feet. Her images, too, are undated and unannotated, except for the names of the mines on Johannesburg’s gold reef where they were taken, and the printer’s name and address: ‘G.B. Neilson, 15 Victoria Street, Georgetown’. The writer of the post indicates that Museum Africa has agreed to add these stereographs to their collections.

I follow up with Diana Wall, collections manager at Museum Africa in Newtown, Johannesburg, and former curator of the Bensusan Museum of Photography, who chats to me at some length about the historical context of these photographs. Diana is not familiar with the name ‘Raymond Neilson’ and says that dating the images precisely is impossible, but they were most likely made around the turn of the 20th century. The stereoscope, she tells me, is typical of those used in Victorian homes for education and amusement; looking at stereographs was a widespread form of entertainment until around 1920 (Wall, pers. comm., 26 May 2014).

Victorian voyeurs

The stereoscope’s heyday followed the popularisation of the device at the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, London, in 1851, where Queen Victoria herself ordered one (Strasser, 1942:117). Popular in Victorian parlours for over half a century, mass-produced stereographs provided entertainment and vicarious travel opportunities for the emerging middle class. In this sense, they were predecessors of later forms of media that occupy a similar niche: cinema, television and the Internet (Spiro, n.d.:3).

Aimed at the sector of society whose consumption fuelled the industrial economy, stereographs reinforced and extended claims supporting and justifying industrial capitalism. Shelley Staples (2002) discusses how turn-of-the-century stereograph depictions of industrial life in America emphasised machinery and products over labourers in industries as varied as textile, lumber, meatpacking and mining. She argues that these images offered ‘standardised views (both aesthetically and ideologically) of labour and industry’, a focus which reflected the rise of technocratic ideas about workers being ‘nothing more than parts of the machinery they work’ (Schlereth, 1991:56). This is certainly the case in the pictures I am looking at: while the miners are in the frame, they remain anonymous, while the machinery is labelled. It therefore seems likely that the stereographs may have been intended as this type of voyeuristic ‘edutainment’.

The act of photography functions as a control mechanism exerted upon the world, upon our experience of it and upon others’ perception of our experience, argues Sontag (1973:2): ‘To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge — and, therefore, like power.’

As Elizabeth Edwards (1992:6), among others, has discussed, the collection of photographic evidence has also been a tool of colonial knowledge production in both the strict sense of, for instance, anthropometric photography and the more ‘leisurely’ sense of the photographic postcards that circulated in Victorian society, creating audiences (Krautwurst, 2009).

Epistemic violence

The will to knowledge as power and dominion: this is the quintessential colonising mindset (cf. Foucault, 1976). These stereographs allowed their audience, from the safety and comfort of their drawing rooms, to see underground into the hot, filthy, dark, dangerous bowels of the earth, to survey and thus to ‘own’ the workings of the very source of the wealth driving the expansion of the South African economy. I imagine that a strange mixture of romance and detachment accompanied this Victorian parlour experience, a voyeuristic frisson and perhaps an element of disavowal, too (Staples, 2002; Lehmann, 2009:100). That the men in the pictures are all unnamed reduces them to mere exemplars of hive workers, stereotypes void of individual identity and thus as interchangeable as ants or moles in burrows, existing in a liminal, abject state, almost already buried alive, even as they engage us with their eyes in the moment of being ‘shot’.

Shot. The thought immediately brings to my mind images of South Africa’s Marikana massacre. On the five-year anniversary of this event, I watched an interview with Joseph Mathunjwa (2017), the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) leader who was present during the Marikana strike negotiations. If colonial photography stripped miners of their individual identities, rendering them nameless cogs in the machinery of the capitalist economy, it is striking that Mathunjwa speaks of the workers in the very same terms: ‘Tomorrow we’ll be gathering at the same koppie [...] commemorating the lives of the comrades who told Capital that “Enough is enough”. We are human beings, we are not just pieces of equipment that [are] thrown underground [to] get the wealth without benefiting from it.’

Photography played a central role in what unfolded at Marikana, too: not only did it shape interpretations and understandings of the massacre after it happened but the presence of cameras in fact changed the course of subsequent events themselves.

In the first weeks after the massacre, what appeared in the press was coloured by partial coverage of the shootings. Owing to restricted access from behind police cordons, photojournalists could only cover what was later understood as ‘Scene One’ of two where shootings occurred that day (Duncan, 2012; Fogel, 2012). From where they stood, journalists saw what appeared to be the armed miners running at police and police opening fire to defend themselves. Later research and aerial footage would show that the miners were in fact herded chaotically in that direction by razor wire cordons, tear gas and rubber bullets as they tried to leave the koppie where they had been congregated in compliance with police orders (see, for example, Rehad Desai’s 2014 documentary film, Miners Shot Down). According to forensic evidence gathered, ‘Scene Two’, out of sight of journalists, was where 17 of the killings took place at close range (Tolsi and Botes, 2015). This was not covered by media until a pivotal investigative piece by Greg Marinovich (2012) appeared in the Daily Maverick, three weeks after the shootings (Alexander et al., 2012; Moodie, 2012).

In this way, a lopsided picture of events appeared in the press, the narrative shaped by Lonmin representatives, police and government, who spun the available footage to their advantage, exonerating themselves from culpability. Jane Duncan has shown that, in coverage of the week before and after the Marikana massacre, the miners themselves were almost absent as news sources. When they were represented, she argues, ‘they had little agency in shaping the coverage and defining its overall direction’. As a result, the story that the viewers of initial news reports were told was that the massacre was, at worst, ‘an example of police panic at the workers’ growing and increasingly violent militancy’ (Duncan, 2013; Rodny-Gumede, 2015). This dominant narrative had already coalesced when more complex perspectives emerged in which surviving miners were directly consulted, such as that of Marinovich and of the book Marikana: A View from the Mountain and a Case to Answer, which was published in December 2012. Duncan, following George Gerbner, calls this silencing of the miners ‘symbolic annihilation’.

Of docile bodies

In thinking about Marikana, I recall my conversation with Museum Africa’s Diana Wall about conditions in the mines for black workers at the turn of the 20th century.

The Victorian stereographs were taken less than 20 years from the day in 1886 when gold was discovered on the Rand. Johannesburg mushroomed out of the veld with the rise of the gold mining industry. People flocked to the cities in search of economic prosperity. To facilitate the extraction of the seams of precious metal from the earth, an enormous reservoir of labour was required that had until then not existed (First, 1961). Government in concert with mine owners set up an ingenious system of laws and controls which coerced workers who had previously lived as subsistence farmers into joining the capitalist machine. Deprived of access to land and subject to taxation, people were forced to enter the wage economy to survive. Many migrated to the mines in search of employment, becoming tied into perpetual servitude by impossibly low wages and the enervating bureaucracy set up to regulate their coming and going.

Through the systematic exploitation of the workers on its lower rungs, South Africa’s burgeoning mining industry enriched society’s privileged upper echelons, sowing the seeds for the vast socio-economic inequalities and abuses that persist to the present day (Legassick, 1975; Callinicos, 1981).

Photographs sometimes allow us to access information about material conditions that may be otherwise obscured. Diana Wall tells me that men had to pay for their own protective clothing from the meagre wages they earned. This would explain why those workers who probably earned the lowest wages, the black workers, do not wear shoes in the stereographs: they were probably unable to afford them.

Bare life. The stereographic images give a literal sense of South African mineworkers living in a paradoxical state of exception akin to Agamben’s Homo Sacer, outside the protection of basic human rights yet simultaneously under total control of the juridical system: constructed as docile black bodies (Foucault, 1976; Agamben, 1995). Each mineworker occupies a role that is utterly essential to the entire economy, yet he remains unindividuated, underground, absent from view as long as no violence erupts. The extreme force and lack of accountability which characterised Lonmin’s and the South African government’s actions to quash the 2012 Marikana miners’ strike reveal that this status of exception continues to the present (cf. Pillay, 2014).

In looking again at the stereographs in relation to coverage of Marikana, it has become clear to me that the precedent for treating mineworkers and, indeed, industrial labourers in general as less than human, as depersonalised inputs, stretches right back to the beginnings of capitalist industrialisation in South Africa. In fact, exploitation in the Marxist sense, which involves the relative devaluation and dehumanisation of the worker, is necessary for profitable business. Corporations have always treated workers as less than fully human, in the sense that their material well-being has always come second to their utility as inputs for production: this instrumentality is a form of objectification. It is thus no surprise that media embedded in an industrial society would reflect this objectifying viewpoint.

The life of a person who is working in the mines is cheaper than even chewing gum.

– Andile Yawa, a relative of one of the victims of Marikana (in Nicolson, 2014)

Historically, the growth of South Africa’s mining industry has tended to be recounted, especially within the industry itself, as a ‘story of “progress” – of modernization, technological achievements, an expanding economy’ (Callinicos, 1981:iv). This is the story told by the stereographs, which named the machines in the pictures yet not the workers. It is a tale of the technical conquest of corporations, which obscures the fact that none of this triumph would have been possible without the backbreaking labour of countless workers who hewed the riches from the ground, bodily.

This is still the story being told. Although the workers now feature in that narrative, they are acknowledged only in lip service paid by mine owners and the South African government to the neoliberal concepts of corporate social responsibility and basic human rights discourse. On the ground, their lives continue to be devalued, and the precarity the stereographs reveal persists. This is borne out by the statistics of broken promises by Lonmin to its workers, which stoked tensions in the build-up to the massacre. For example, of a promised 70 hostel block upgrades and 3,200 new houses by 2009, only 29 upgrades and three houses were delivered by that year (Lewis, 2017).

What I take from this example is that the mineworkers’ human needs – for shelter and decent housing, for security and warmth, for fair remuneration – have been neglected. As long as they have showed up for work, as long as they have continued to extract the precious minerals from the ground, mine owners have been content to let these needs go unaddressed and to leave their own promises unfulfilled (Frankel, 2012; Lewis, 2017). The Marikana survivor Mzoxolo Magidiwana’s speech, given in May 2017 at the annual general meeting of BASF (reproduced in this book), underlines how mineworkers continue to be regarded as inputs rather than as human beings deserving of the dignity and care accorded to other people in society. Viewed from this angle, the Marikana massacre itself was just an extreme example in a long history of treating the lives of workers as expendable.

Yet, despite this abjection, in how they live their lives and in representing themselves, workers have insisted on their humanity being recognised. This, too, has always been the case. The choreographed stereographic tableaux in which miners were posed as dutiful units of labour power belie the rich ways in which workers on the Witwatersrand did find means for self-representation, exercising sophisticated, creative agency despite the conditions they endured (Abrahams, 1946; Tracey, 1952; First, 1961; Callinicos, 1981; Coplan, 1994; Van Onselen, 2001; Allen, 2005). Their stories and songs have rarely reached audiences beyond their own communities.

While the oppression of the capitalist system endures, compounded by the legacy of apartheid and racism, there have been paradigmatic shifts in critical social perspective between the moment of the stereographs’ origin and the present. As one example, there is now a greater space for narratives that speak of the agency of labourers, even as mainstream media representations still tend to elide their perspectives (Nicolson, 2014; Tolsi and Botes, 2015).

The iconic photographic image by City Press journalist Leon Sadiki of rock drill operator and strike leader Mgcineni Noki (also known as ‘Mambush’ and the ‘Man in the Green Blanket’) testifies to this. This image of Mambush raising his fist and his voice, bright green blanket pinned around his shoulders as he addressed striking Lonmin workers just hours before he and 33 others died in a hail of police bullets, has broken loose from its immediate context and come to stand for resistance to corporate and government oppression in general. Now it is used in other struggles: a stylised stencil of the figure, created by the Tokolos collective (www.tokolosstencils.tumblr.com/), makes a regular appearance in South African urban space, usually accompanied by the words ‘REMEMBER MARIKANA’ or ‘WE ARE ALL MARIKANA’.

This image is being mobilised in a wider public domain, drawing mainstream attention to the plight of working-class people in South Africa, despite continued efforts by neoliberal corporations and government to maintain the status quo that would hold mineworkers and other labourers in silent servitude.

References

Abrahams, P. (1946) Mine Boy, Dorothy Crisp & Co., London

Agamben, G. (1995) Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Stanford University Press, Stanford

Alexander, P. et al. (2012) Marikana: A View from the Mountain and a Case to Answer, Jacana, Johannesburg

Allen, V. (2005) The History of Black Mineworkers in South Africa, 3 vols.), The Moor Press, Keighley and Merlin, London

Barthes, R. (1981) Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Hill and Wang, New York

Berger, J. (1972) Selected Essays and Articles: The Look of Things, Penguin, London

Callinicos, L. (1981) A People’s History of South Africa, Volume One: Gold and Workers 1886–1924, Ravan Press, Johannesburg

Coplan, D. (1994) In the Time of Cannibals: The Word Music of South Africa’s Basotho Migrants, University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Desai, R. (2014) Miners Shot Down, documentary film, RSA, 90 mins, Uhuru Productions, Johannesburg

Duncan, J. (2012) Marikana and the problem of pack journalism, SABC News.com, www.sabc.co.za/news/a/00f7e0804cfe58899b00bf76c8dbd3db/Marikana-and-the-problem-of-pack-journalism-20121007, accessed 15 November 2014

Duncan, J. (2013) South African journalism and the Marikana massacre: A case study of an editorial failure, The Political Economy of Communication 1, 2, polecom.org/index.php/polecom/article/view/22/198, accessed 5 October 2017

Edwards, E. (1992) Introduction, in Anthropology and Photography 1860–1920, Yale University Press, New Haven, in association with the Royal Anthropological Institute, London

First, R. (1961) ‘The gold of migrant labour’, in D. Pinnock, Voices of Liberation, HSRC Press, Cape Town, 2012, pp. 118–140

Fogel, B. (2012) The selling of a massacre: Media complicity in Marikana repression, Ceasefire, Monday, 5 November, ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/south-africa-marikana/, accessed 9 October 2017

Frankel, P. (2012) Marikana: 20 years in the making, IOL Business Report – Opinion, 21 October, www.iol.co.za/business-report/opinion/marikana-20-years-in-the-making-1407448, accessed 19 October 2017

Foucault, M. (1976) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Pantheon, New York

Krautwurst, U. (2009) The joy of looking: Early German anthropology, photography and audience formation, in A. Hoffmann (ed.), What We See: Reconsidering an Anthropometrical Collection from Southern Africa: Images, Voices, and Versioning, Basler Afrika Bibliographien, Basel

Legassick, M. (1975) South Africa: Forced labour, industrialisation and racial differentiation, in R. Harris (ed.), The Political Economy of Africa, John Wiley, New York

Lehmann, A. (2009) Exposures: Visual Culture, Discourse and Performance in Nineteenth-Century America, Stauffenburg, Tübingen

Lewis, P. (2017) Marikana: Lonmin’s dodgy housing record, GroundUp, 4 September, www.groundup.org.za/article/marikana-lonmins-dodgy-housing-record/, accessed 10 October 2017

Marinovich, G. (2012) The murder fields of Marikana: The cold murder fields of Marikana, Daily Maverick, 8 September, www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2012-08-30-the-murder-fields-of-marikana-the-cold-murder-fields-of-marikana, accessed 19 October 2017

Mathunjwa, J. (2017) WATCH: AMCU boss speaks about Marikana 5 years after the massacre, ENCA.com, video interview with Joseph Mathunjwa, published 16 August, www.enca.com/south-africa/watch-amcu-boss-speaks-about-marikana-5-years-on-since-the-massacre, accessed 19 October 2017

Moodie, G. (2012) Where were the miners’ voices at Marikana?, Journalism.co.za, 15 October, www.journalism.co.za/index.php/news-and-insight/insight/170-backstory/5097-where-were-the-miners-voices-at-marikana.html, accessed 20 August 2017

Nicolson, G. (2014) Marikana Commission: Families speak, Daily Maverick, 14 August, www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2014-08-14-marikana-commission-families-speak, accessed 5 October 2017

Pillay, S. (2014) Marikana: The politics of law and order in post-apartheid South Africa, Al Jazeera, 21 March, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/09/2012916121852144587.html, accessed 15 November 2014

Rodny-Gumede, Y. (2015) Coverage of Marikana: War and conflict and the case for peace journalism, Social Dynamics, 41, 2, pp. 359-374

Schlereth, T. (1991) Victorian America: Transformations in Everyday Life, 1876–1915 (The Everyday Life in America Series, vol. 4), Harper Collins, New York

Sekula, A. (1982) On the invention of photographic meaning, in V. Burgin (ed.), Thinking Photography, Macmillan, London

Sekula, A. (2003) Reading an archive: Photography between labour and capital, in L. Wells (ed.), The Photography Reader, Routledge, London and New York

Sontag, S. (1973) In Plato’s cave, in On Photography, first electronic edition (2005), RosettaBooks, New York

Sontag, S. (1977) Photography unlimited, New York Review of Books, 24, 11, 23 June, www.nybooks.com/articles/1977/06/23/photography-unlimited/, accessed 5 October 2017

Spiro, L. (n.d.) A brief history of stereographs and stereoscopes, Part 1 of a 4-part course, History through the Stereoscope, cnx.org/contents/s3OUU76y@5/A-Brief-History-of-Stereograph, 5 October 2017

Staples, S. (2002) The machine in the parlor: Naturalizing and standardizing labor and industry through the stereoscope, American Studies Program, Fall 2002, University of Virginia, www.xroads.virginia.edu/~ma03/staples/stereo/home.html, accessed 5 October 2017

Strasser, A. (1942) Victorian Photography, Focal Press, London and New York

Tagg, J. (1988) The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories, Macmillan, London

Tolsi, N. and P. Botes (2015) Marikana: The blame game – A special report, laura-7.atavist.com/mgmarikanablamegame, accessed 20 August 2017

Tracey, H. (1952) African Dances of the Witwatersrand Gold Mines, African Music Society, Johannesburg

Van Onselen, C. (2001) New Babylon, New Nineveh: Everyday Life on the Witwatersrand 1886–1914, Jonathan Ball, Johannesburg