3

WAR OF THE RATS

On 12 September Hitler ordered General Paulus to fly to a council of war at his Werewolf command centre in Vinnitsa. This complex of log cabins in the Ukrainian forest, Hitler‘s forward headquarters, was a full 700 miles (1,100km) behind the front line at Stalingrad, but being here made him feel close to the action.

The Führer was upbeat, almost hopping with anticipation. He had just had a reshuffle of his top commanders, in which he had weeded out the defeatists and weaklings as he saw them. Among those to go was Franz Halder, who was the closest thing to a voice of reason in Hitler‘s immediate entourage. Other victims were Field Marshal Sigmund List, whose progress in conquering the Caucasus was deemed too slow. Two of the Panzer corps commanders at Stalingrad were also sacked for dawdling. Now, with right-thinking Nazis in all the key posts, and with his Sixth Army poised for a massive assault, Hitler was certain that Stalingrad would soon cease to be a problem. He had made plans for after the battle: the entire male population of this ‘shrine of communism‘ was to be shot. As for the women and children, Hitler gave no specific orders. Presumably they were to be deported to the west as slave labour, like other unfortunate civilians captured in the earlier phase of Operation Blue.

Paulus, before his arrival at the Vinnitsa conference, had assured his master in a memo that the subjugation of the city should not take more than ten days at most once the offensive began. He had 170,000 men on the start line, ready and waiting to punch their way through the city to the Volga landing stages. The massive infantry force was supported by 500 tanks and 3,000 big guns and mortars. Behind this mailed fist was an equal number of reserves. Moreover, German air superiority was overwhelming: von Richthofen’s planes ruled the polluted skies over the city. The Russians, on the other hand, had only 54,000 trained soldiers inside Stalingrad. They possessed barely 100 tanks, and most of their artillery was on the far side of the Volga. And many of the people manning the outer defences were women and factory workers who barely knew how to use a gun.

If, on the eve of battle, Paulus had any personal doubts about his ten-day timetable, he kept them to himself. The odds seemed stacked in his favour, and in any case he had half an eye on the promotion he was hoping to receive once the Stalingrad campaign was over: he had heard rumours that he was in line for the post of Chief of the German Armed Forces High Command. So all in all, firm-jawed optimism was the order of the day at Werewolf HQ.

By coincidence, on that same day - 12 September - Stalin summoned General Zhukov to a crisis meeting at the Kremlin in Moscow. The previous week, Zhukov had failed to slice through the German corridor north of Stalingrad. Three Russian armies - the First Guards, the 21st and the 66th - had been held off by a very professional German defence. This meant the enemy now had a strong grip on the Volga and could impede the supply line from the far bank: a choking hand at the throat of the city. The 62nd Army inside Stalingrad was completely cut off, and weakening by the hour. Stalin wanted to know what Zhukov planned to do about it.

The session was held late in the evening - Stalin’s favourite time for holding court and for desk work. The Red Army’s General Chief of Staff, Alexander Vasilievsky, was also there. Like Halder for Hitler, he was wont to express the sensible military view of matters when political considerations were too much to the fore; unlike Halder, he was on his way up rather than on the way out. Vasilievsky was a natural ally for Zhukov, who recalled the meeting in his post-war memoirs.

Vasilievsky reported on the movement of new German forces toward Stalingrad from the direction of Kotelnikovo, on fighting near Novorossisk, and on the German drive toward Grozny. Stalin listened closely and then summed up: ‘They want to get at the oil of Grozny at any price. Well, now let‘s see what Zhukov has to say about Stalingrad.‘

I repeated what I had told him by telephone, adding that the 24th, 1st Guards and 66th armies, which had taken part in the battle of September 5th to 11th, were basically good fighting units. Their main weakness was the absence of reinforcements and the shortage of howitzers and tanks needed for infantry support. The terrain on the Stalingrad Front was extremely unfavourable to us - it was open terrain dissected by deep gullies that provided excellent cover for the enemy. Having occupied a number of commanding heights, the Germans could now manoeuvre their artillery fire in all directions. In addition, they could also direct long-range artillery at our forces from the area of Kuzmichi, Akatovka and the experimental state farm. Under those conditions, I concluded, the 24th, 1st Guards and 66th armies of the Stalingrad Front were unable to break through the enemy defences.

‘What would the Stalingrad Front need to eliminate the enemy corridor and link up with the Southeast Front?‘Stalin asked.

‘At least one full-strength field army, a tank corps, three tank brigades and four hundred howitzers. In addition, the support of at least one air army during the time of the operation.‘

Vasilievsky expressed agreement with my estimate. Stalin reached for his map showing the disposition of Supreme Headquarters reserves and studied it for a long time. Vasilievsky and I stepped away from the table and, in a low voice, talked about the need for finding another way out.

‘What other way out?‘ Stalin suddenly interjected, looking away from the map. I had never realized he had such good hearing. We stepped back to the map table. ‘Look,‘ he continued, ‘You had better get back to the General Staff

and give some thought to what can be done at Stalingrad and how many reserves, and from where, we will need to reinforce the Stalingrad group. And don’t forget about the Caucasus Front. We will meet again tomorrow evening at nine.’

Zhukov and Vasilievsky spent all the next day sketching out a plan that was far grander and more ambitious than merely breaking through to Stalingrad from the north. In the course of that single day they came up with the blueprint for a massive counter-offensive, a giant encirclement deep in the rear of the German Sixth Army. They envisaged a pincer movement that would swallow the Germans whole, like the jaws of a python stretching around a big fat rat. Once the Germans were held tight, Zhukov would lay siege to the besiegers of Stalingrad and destroy them.

But this plan, dizzying in its scope, depended entirely on one highly suspect assumption: that the Germans would not be able to take Stalingrad while it was being prepared. Zhukov and Vasilievsky calculated that it would take six weeks to amass the vast numbers of men and tanks required - and yet there was every chance that Stalingrad would fall in the next 48 hours. But Zhukov thought it could be done, and was sure that this one big blow was a better idea than frittering away army after army on a series of small-scale operations. All the same, there was no way of knowing if Stalin would agree. Zhukov recorded that:

In the evening of September 13th, Vasilievsky called Stalin and said we were ready to report. Stalin said he would be busy until ten o’clock and that we should come at that time. We were in his office at the appointed hour.

He greeted us by shaking hands (which he seldom did) and said with an air of annoyance: Tens and hundreds of thousands of Soviet people are giving their lives in the fight against fascism, and Churchill is haggling over twenty Hurricanes. And those Hurricanes aren’t even that good. Our pilots don’t like them.’ Then, in a quiet tone without any transition, he continued: ‘Well, what did you come up with? Who‘s making the report?‘

‘Either of us,’ Vasilievsky said. ‘We are of the same opinion.‘

Stalin stepped up to the our map. ‘What have you got here?‘ he asked.

‘These are our preliminary notes for a counteroffensive at Stalingrad,‘ Vasilievsky replied.

‘What are the troops at Serafimovich?‘

‘That would be a new front. We will have to set it up to launch a powerful thrust into the rear of the German forces at Stalingrad.‘

‘We don‘t have the forces now for such a big operation.‘

I said that according to our calculations we would have the necessary forces and could thoroughly prepare the operation in forty-five days.

‘Wouldn‘t it be better to limit ourselves to a thrust from north to south and from south to north along the Don?‘ Stalin said.

I explained that the Germans would then be able to shift their armoured forces from Stalingrad and parry our thrusts. An attack west of Don, on the other hand, would prevent the enemy from quickly manoeuvring his forces and bringing up the reserves - because of the river obstacle.

‘Aren‘t you out too far with your striking forces?‘ Stalin said.

Vasilievsky and I explained that the operation would proceed in two stages: after a breakthrough of the German defences, the enemy’s forces at Stalingrad would be surrounded and a strong outer front would be created, isolating his forces from the outside; then we would proceed to destroy the trapped Germans and stop any attempts to come to their aid.

‘We will have to think about this some more and see what our resources are,‘ Stalin said. ‘Our main task now is to hold Stalingrad and to keep the enemy from advancing toward Kamyshin.’

At that point Poskrebyshev walked in and said Yeremenko was on the phone.

After his talk with Yeremenko, Stalin said, ‘ Yeremenko says the enemy is bringing up tank forces near the city. He expects an attack tomorrow.’

Turning to Vasilievsky Stalin added ‘Issue orders immediately to have Rodimtsev’s 13th Guards Division cross the Volga, and see what else you can send across the river tomorrow.’

So on that September night, when the full might of the Sixth Army was about to be unleashed on Stalingrad, the foundation stone of the eventual Russian triumph was laid. To adopt the plan for a counter-attack in November was an enormous act of faith on the part of Stalin and his generals. It was a seed of victory sown in secret.

But another event occurred on that day of meetings, one that went unremarked at the Kremlin but was almost as significant for the outcome of the battle as Zhukov’s grand design. On 12 September, Vasily Chuikov formally took command of the 62nd Army inside Stalingrad, and so became Paulus’s chief adversary.

The two opposing generals could hardly have been more different. Paulus was aloof, fastidious, always immaculately turned out. He was a gifted administrator rather than a front-line commander, and sometimes seemed to find the passion and squalor of war somewhat distasteful. Chuikov, on the other hand, was a son of the peasantry. In uniform he was irredeemably scruffy - something his contemporaries always joked about. He was naturally pugnacious and had the broad nose and beetle brow of a boxer or a street fighter (his father was locally famous as a wrestler). As a commander, Chuikov was ruthless and unforgiving towards subordinates who failed him. At the same time, he was congenitally incapable of despair. Most of all, he had the special gift, granted to some war leaders, of being able to imbue his army with his personality, to make it an extension of his own stern will. Almost from the moment Chuikov appeared in their midst, the men of the battered 62nd became as unshakeable and indomitable as Chuikov himself And they needed to be, because on the morning of 13 September the Germans smashed into their lines like a giant steam hammer crashing into a brick wall.

ANNA, A PRISONER OF WAR

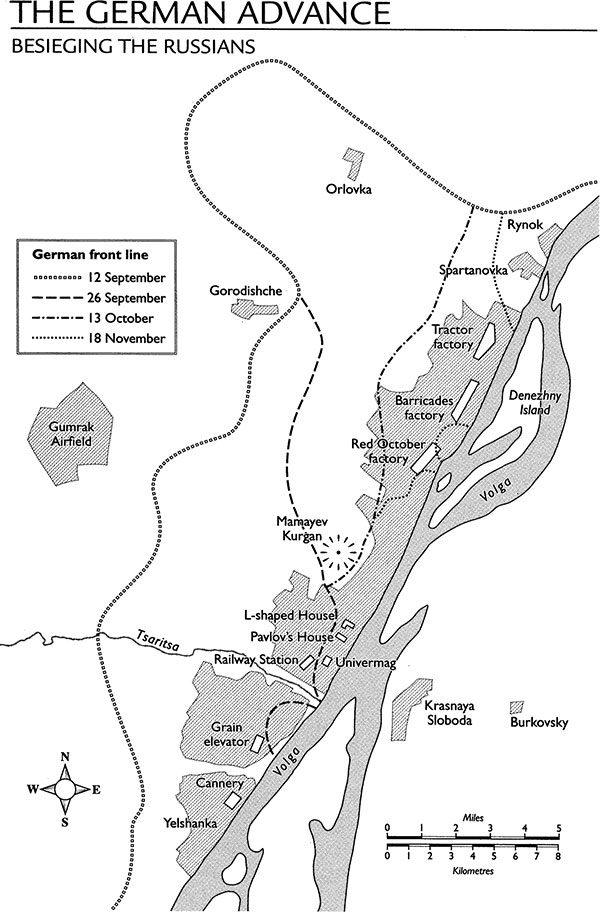

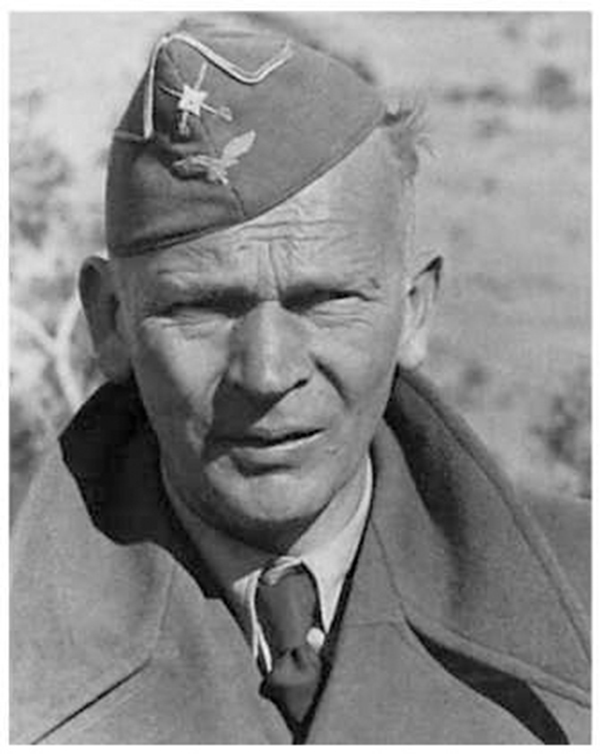

On 12 September 1942, the German front line at Stalingrad was 30 miles (48km) long. In the north it formed a wide loop around the factory district, taking in the village of Orlovka. But a little further to the south the Germans were ranged closer to the city. Their forward positions formed an undulating line that ran more or less parallel to the Volga at a distance of about 5 miles (8km). South of the Tsaritsa they were nearer still - about 2 miles (3.2km) from the river - and they had contact with the Volga beyond the southern reaches of the town. So on the eve of battle the Germans were still some way outside the city limits. But that was about to change.

The two-pronged German attack began on the 13th, and was directed mainly at the southern half of the city. First came a day-long artillery bombardment that created a dirty pink fog of smoke and brick dust over the city. Then, while the German 295th Infantry Division raced for the hilltop of Mamayev Kurgan, the 71st and 76th Divisions struck out diagonally from Gumrak towards the central landing stage. Meanwhile, the 94th Infantry Division and the 24th Panzer Division drove like a steel nail through the southern suburbs of the city, heading north-east towards the same finish point on the riverside.

Anna Andreyevskaya was a nurse attached to a Russian unit south-west of the city. When the Germans reached her on the first morning of the attack, she was plunged into an ordeal that she survived only by bringing her own courage and quick-wittedness to bear.

We had nothing to respond to the Germans’ fire with - only the commanders had machineguns, said Andreyevskaya. All our signallers had been killed. So when at nine o’clock in the morning the Germans went through us with their infantry and tanks, it was all over. We were taken prisoner.

I had crawled into the observation post to bandage the wounds of the deputy company commander. He died in my arms. I stayed in the observation post. It would have been madness to leave it, since the Germans were outside, only 20 metres away.

Merzlov, the regiment’s senior political officer, jumped into the observation post along with four signallers. In addition to myself, there were another three signallers in the observation post, two of them wounded in the legs. The senior political officer said that he would admit anyone who so wished into the Communist Youth League, but it turned out that we were all already members. ‘If I die, consider me a Party member,’ I said to Merzlov. ‘Very well, from this moment on you are a member of the Communist Party,’ he replied. We shook hands.

The political officer was in the process of telling us where to direct our fire when I heard a terrifying noise, like a loud crack. When I lifted my head, the dugout was full of suffocating smoke and dust. And at the entrance where Merzlov and the four signallers had been standing there was now a gruesome pile of lumps of flesh, bones, clothes and smashed rifles.

By some miracle, I was still alive, though I had a pain in my side from being hit by something. I sat down on a shelf that had been made in the dugout wall, and when the Germans started throwing grenades into the dugout’s passage I instinctively bent my head down onto the chest of the dead deputy company commander. I remained sitting in this position, as if frozen. I could hear German voices around the dugout. I was afraid the Germans would rape me.

I pulled out my revolver and put the muzzle to my temple. I could already feel the touch of the steel when I realized that it was preposterous for a strong, healthy person to end her own life. Captivity would be terrible, but perhaps I could be of some use to the Motherland even in captivity? Perhaps I would be able to escape. Perhaps the regiment would send reinforcements and save us. If I were already dead, it would all be in vain. No then. What will be will be. I put my revolver back in its holster.

Then a German officer jumped into the dugout. He started picking up map-cases, weapons and compasses. When he spotted me, his eyes widened. ‘Weib? Weib? Woman?’ he said, and made a grab at my chest. I pushed his hands away. ‘Weib,’ I said, and told him to stop touching me. I took off my map-case and handed over my revolver. He was especially pleased with the map-case. He shook everything inside it straight onto the bloody pile, taking only my diary. ‘Das ist Dokument, ’ he said.

Anna was kept under guard for some time in the dugout where her comrades had been killed. Around midday she was joined by some other prisoners-of-war, men from her own unit.

A German radio operator had set up his equipment in the dugout’s passage (I could hear its cheeping sound), and he was sitting on a shovel that he had rammed into a slope in the dugout’s walls. Then three soldiers from my company jumped into the dugout. ‘Anna, you’re alive!’ they shouted in utter amazement. ‘The Germans have taken two of our battalions prisoner ...’ Until that moment, I had been sitting there completely motionless, frozen to the spot. To block out what was happening to me and what might lie in store for me, I instinctively distracted myself from all terrifying thoughts. I started thinking about the words I would use ‘later on’ to describe what was happening to me. I have always considered myself a writer. But on hearing my comrades’ words I took heart: ‘Well there’s something to live for, there’s a purpose!’

Towards evening, the Germans settled down to eat their dinner. They were talking quietly. Several men peeped into my bunker, one at a time, and looked at me as if I were some kind of exotic wonder. I started to be gripped with fear: would I still be here when night came? Finally, I made up my mind.

I stood up, went out of the dugout and addressed one of the soldiers in German: I wish to speak to your officer.‘ He listened to me attentively and immediately fetched an officer. I saluted him and said: I wish to see your most senior commander. Take me to him.’ And this officer took me to the very dugout in which I had lived before the Germans came. Only now it was different: they had already replaced some of the furniture. There were many officers in this dugout, all of them handsome and cultured-looking. I couldn’t help noticing this.

The officer offered me a chair and asked me to wait. Finally, someone came up to me who I assume was their most senior commander, as everyone else there leapt to their feet and stood to attention. He sat down at a table and said to me, ‘Was wollen Sie? What do you want?’

I replied, in German, that I wanted him to send me to the wounded Russian prisoners. The German officer listened to me approvingly and then switched to Russian. He said that he had lived in Russia for a while, and ordered some officer to drive me to the Russian prisoners. I thanked him, saluted, and headed for the exit. ‘Perhaps there’s something else you want?’ I heard this same officer say (I never did make out his rank). I turned around: ‘Nothing! Thank you.’

Half an hour later, I was with my fellow Russians! They greeted me as if I was one of the family. I immediately did the rounds of everyone there. There were many wounded. They had had nothing to eat or drink since the morning, and it was a hot day. The following day, the Germans lined us up into a column. They had gathered all their wounded from the battlefield and they forced us Russians to carry them, on either our capes or our overcoats. We spent the night in Novoalexeyevka, on an empty patch of land surrounded by barbed wire, and in the morning we were driven to a camp for Soviet POWs, in Kalach.

THE GRAIN ELEVATOR

By now the offensive had moved up the edge of the city. On the second day of the onslaught, the men of the 94th Infantry and the 24th Panzer could see the huge bulk of Stalingrad’s grain elevator, looking like a beached aircraft carrier on the near horizon. Willi Hoffman was with the 267th Regiment of the 94th Infantry Division as it marched into the city. We can see the Volga,’ he wrote in his diary. ‘But everywhere you look there is fire and flames. Russian cannon and guns shoot from within the burning city. They are fatalists, fanatics.’ This note of grudging admiration for the enemy is a niggling presence in his diary entries over the next few days.

13th September. A bad date, our battalion was very unlucky. The katyushas inflicted heavy losses this morning: 27 killed and 50 wounded. The Russians fight with the desperation of wild beasts; they won’t allow themselves be taken prisoner, but instead let you come up close and then they throw grenades. Lieutenant Kraus was killed yesterday, so now we have no company commander.

16th September. Our battalion is attacking the grain elevator with tanks. Smoke is pouring out of it. The grain is burning and it seems that the Russians inside set fire to it themselves. It’s barbaric. The battalion is taking heavy losses. Those are not people in the elevator, they are devils and neither fire nor bullets can touch them.

The grain elevator was an unappealing piece of industrial architecture, about the size of a Norman castle, and just as impregnable. The concrete silos - about eight storeys high - stood side by side forming a solid, windowless mass. A kind of tower containing a staircase abutted one end of the concrete massif and led to a long flat storey atop the silos. This had a row of windows like the portholes on a ship - each one now bristling with guns. Inside the elevator was a small band of Red Army men - the apparently indestructible devils who so exasperated Hoffman. But they were a dwindling band: they could not hold out alone, so a section of the 92nd Independent Rifle Brigade, naval infantrymen of the Far Eastern Fleet, was on its way to reinforce them. When Stalin had told Vasilievsky to ‘see what else you can come up with‘, these Siberian sailors were what he pulled out of the bag.

The 92nd Brigade arrived on the right bank of the Volga in their sailors‘ uniforms during the small hours of 16 September, when the German offensive was well under way. The sailors fought until nightfall. After this baptism of fire, one unit under the command of Andrei Khozyainov was given the elevator mission.

On the night of the 17th, after a fierce battle, I was called to the battalion command post and given the order: take a platoon of machinegunners to the grain elevator and, together with men already there, hold it at all costs.

That same night we arrived at the place we were told to go and report to the garrison commander. At that time, the elevator was being held by a battalion of not more than thirty to thirty-five guardsmen. There were also the wounded, some slightly, some seriously, who they had not yet been able to send back to the rear.

On the night that Khozyainov arrived in the elevator with his men, this building became the white-hot focus of the battle for Stalingrad. Forty-odd souls were holding out inside the elevator against the combined weight of three divisions. Khozyainov‘s arrival increased, the tired defenders‘ fighting strength by a mere 18 men.

The guardsmen were very pleased to see us, and immediately began cracking army jokes and making funny remarks. We had two Maxim guns, one light machinegun, two anti-tank rifles, three tommyguns and a radio set.

At dawn on the 18th a German tank carrying a white flag approached from the south. ‘What‘s going on?‘ we thought. Two men showed themselves from inside the tank, a Nazi officer and an interpreter. Through the interpreter the officer tried to persuade us to surrender to the ‘glorious‘ German army, as defence was useless and there was no point in our sitting it out any longer. ‘Get out of the elevator now,’ insisted the German officer. ‘If not we will show you no mercy. In one hour‘s time we will bomb you all flat.‘

‘What a cheek,‘ we thought, and gave the Nazi lieutenant a curt reply: Tell all your fascists they can go to hell in an open boat! You two ‘voices of the people‘ can go back to your lines, but only on foot. The German tank tried to back away, but a volley from our two anti-tank rifles stopped it.

Soon after that enemy tanks and infantry about ten times our strength attacked from south and west. After the first attack was beaten back a second began, then a third, and all the while a reconnaissance plane circled over us. It corrected the fire and reported our position. Ten attacks were beaten off just on September 18th.

We were very careful with our ammunition, as it was a long way to bring up more, and a difficult trip. In the elevator the grain was on fire, and the water in the machineguns evaporated. The wounded kept asking for something to drink, but there was no water nearby. This was how we defended our position, day and night. Heat, thirst, smoke - everybody’s lips were cracked.

During the day many of us climbed up to the high points in the elevator and from there fired on the Germans, especially at their snipers. At night we came down and made a defensive ring. Our radio set had been put out of action on the first day of the battle, so we had no contact with our units.

The Russians held out in their makeshift citadel in this way for a further three days and nights, until they were weak with hunger and half crazed with thirst. To keep their water-cooled machineguns from seizing up, they had to urinate into the casing. On 20 September the Germans launched their most determined and ferocious attack yet.

Around noon, twelve enemy tanks came up from the south and west, continued Khozyainov. To our dismay, we had already run out of ammunition for our anti-tank rifles, and we also had no grenades left. The tanks approached the elevator from two sides and began to fire at our garrison almost at point-blank range. We continued to fire our machineguns and tommyguns at the enemy’s infantry, to stop them from entering the elevator. Then a Maxim was blown up by a shell together with its gunner, and in another part of the elevator the casing of the second Maxim was hit by a piece of shrapnel, bending the barrel. All we had left was one light machinegun. Concrete was raining down on us after each explosion, and the grain was in flames. Even at a metre’s distance, we could not see one another for dust and smoke. We shouted to each other - ‘Hurrah!’ and ‘All hands on deck’ - to keep our spirits up.

Soon German tommygunners appeared from behind the tanks. There were about two hundred of them. They went into the attack very cautiously, throwing grenades ahead of themselves. We were able to catch some of the grenades and throw them straight back. Every time the Germans got close to the walls of the elevator we would shout out again: ‘Hurrah!’ ‘Onward!’ ‘For the motherland!’ ‘For Stalin!’

On the west side of the elevator the Germans managed in spite of us to enter the building, but we immediately covered the areas they had occupied with gunfire. Fighting raged inside the building. We were so close to the enemy that we could feel and hear their breath, their every movement, but we could not see them. We fired at noises.

That evening, during a short lull, we counted our ammunition. It turned out there was not much left: one and a half drums for the machinegun, twenty to twenty-five rounds for each tommygun, and eight to ten rounds for each rifle. It was impossible to defend ourselves with that amount of ammunition. We were surrounded by tanks and infantry, no more than 60 metres away. We decided to break out to the south, towards Beketovka, as enemy tanks were cruising back and forth to the north and east of the elevator. We set off during the night of the 20th. To begin with all went well; the Germans were not expecting us here. We passed through the gully and crossed the railway line, then happened on an enemy mortar unit which was just taking up position in the darkness.

We overturned the three mortars and a wagon-load of bombs. The Germans scattered, leaving behind seven dead. They not only abandoned their weapons, but left behind bread and water too. And we were faint with thirst. ‘Something to drink! Something to drink!’ was all we could think. We drank our fill in the darkness.

And so the elevator was lost - but the defenders had done enough to hold the Germans up, to keep them from gaining a stronger foothold on the banks of the Volga. At the time, the Germans failed to see that this was a pyrrhic victory, won at far too high a cost. But the appalled Willi Hoffman almost admitted as much to his diary:

22 September. We have broken the resistance of the Russians in the elevator building. We have reached the Volga. We found about forty corpses in the elevator. About half of them are sailors - sea devils, they are. We took one prisoner. He is badly wounded and can’t speak, or pretends he can’t. Our battalion is now reduced to less than the ordinary complement of a company. None of our old soldiers can remember fighting as barbarous as this.

26th September. Our regiment is still engaged in constant heavy fighting. The Russians continue to resist just as stubbornly now that we have taken the elevator. You can‘t see them: they hide in the buildings and basements and strike at us from all sides - even from the rear. Such barbarians, to use gangster tactics against us. Russian soldiers have suddenly reappeared in a sector which we occupied two days ago, and the battle has begun all over again. Our people are getting killed not just in the front line, but in rear sectors that we already have.

It was perhaps unreasonable of the Germans to expect the Russians to fight in a civilized manner. But the 94th Infantry Division did not care. They were just pleased to have cracked the hardest nut in this part of town. General Paulus felt the same. He saw the capture of the grain elevator as a symbolic victory for his men. So confident was Paulus that he now found time to design a campaign badge for his army. It took the form of a shield depicting the grain elevator as seen from the west, the Germans‘ main direction of attack, and it had the word ‘Stalingrad‘ in bold Gothic script beneath it. Paulus gave his sketch to a regimental artist to work up, but that was as far as it went. The Sixth Army‘s victory badge remained on the drawing board. It was never to be anything more than a general‘s doodle.

CITY ON THE BRINK

And yet three days into the attack, things were looking very good for the Germans. The Luftwaffe continued to enjoy the easy pickings. ‘The last few days have been pretty hectic, three to four assaults a day,‘ wrote Manfred S—, a fighter pilot.

I‘ve notched up two Russians that I brought down, and others that don‘t count as I didn‘t have a witness, and I couldn‘t keep my eyes on them as they crashed. We moved our base forward a bit yesterday, to be closer at hand.That means being constantly at the ready of course, and here the nights are considerably noisier. It’s quite amazing how quickly we’ve settled into a new place. Up to now the weather has been fantastic. It hasn’t been decided yet whether we’ll be spending the winter here.

The protective wing of the Luftwaffe was much appreciated by the ground troops as they advanced. One soldier wrote home: ‘Yesterday morning, after hard defensive battles north of Stalingrad, we went back on the offensive towards the heavily defended city. The battle is still very much under way, and the city is entirely obscured by clouds of smoke. Above us, our Luftwaffe is working tirelessly, and fierce dogfights can be seen all the time. We hope this bulwark of Bolshevism will be in our hands very soon.’ Even behind the front line there was much evidence of destruction to cheer the heart of a German Landser - even if now the prospect of a speedy return home was fading.

I had the opportunity to drive across the area where one of the greatest Panzer battles over the last days took place, wrote Corporal Otto K— in a letter home. A vast, steppe-like, slightly hilly terrain, and across it as far as the eye can see shot-up and burnt-out tanks - and Russian ones at that. There are hardly any German ones among them, I only saw a single one, proof of the excellence of the German weapons.

The general feeling is that the troops will be staying here over the winter, so for the immediate future we don’t expect there to be much going on, so you needn’t worry about me. There are many German aircraft about, only the occasional Russian one, so by and large the Russian Air Force doesn’t seem to be such a threat, at least not on this part of the front. For days at a time the Russian brothers keep themselves out of sight - Göring’s boys are seeing to that.

The corporal will surely have come to rue his casual attitude to the Russian winter: it was probably the death of him if he survived long enough to see it. But for now it was the Russians who had reason to be worried. Late in the evening of 16 September, an NKVD officer named Selivanovsky filed a secret report to Lavrenty Beria, Stalin’s deeply sinister chief of police. Selivanovsky’s job was to spy on his own side, and his report is first and foremost a summary of the state of morale inside the city and the army: are there traitors, wreckers or cowards? Is anyone voicing criticism of the country’s leaders? Selivanovsky’s notes are written in the dry, lugubrious tone adopted by policemen everywhere when they put pen to paper; and he is overly pessimistic about the loss at the grain elevator, which was very much still in the fight at this time. But despite these inaccuracies, the police report provides a vivid snapshot of the situation in Stalingrad at that precarious moment. It is a picture of a city on the very brink of defeat. Here is Selivanovsky’s memorandum:

As of24.00 on the 15th of September, the enemy in Stalingrad has occupied the grain elevator, which has been penetrated by up to 40 enemy tanks and groups of enemy motorized infantry. The enemy also has the House of Specialists, situated right next to the Volga, 150-180 metres from the crossing. The enemy has moved more than 20 tanks, and groups of sub-machinegunners and mortar men up to this location.

The railway depot, the former building of the State Bank and a number of other buildings have been occupied by enemy sub-machinegunners, who have turned them into strong points. The enemy has captured Mamayev Kurgan (which dominates all Stalingrad and the left bank of the Volga) thereby taking control of all the crossings and roads leading to Krasnaya Sloboda.

Stalingrad was completely unprepared for its defence. No fortifications had been erected on the streets, and no underground depots of munitions, medical supplies and provisions had been dug. After only one day of street battles, the units completely ran out of munitions. Ammunition and provisions are now having to be brought across the Volga, by the only crossing still in operation, and only at night.

For several days now, the enemy has been shelling the Volga crossings and raking them with sub-machinegun fire, and three of the four working ferryboats are currently disabled. Enemy aircraft are still subjecting our units and the city of Stalingrad to continuous bombardment.

There are still instances of disorganization and carelessness. On the night of the September 15th, I personally went out into Stalingrad and established that the command post of the 13th Guards‘ Infantry Division and the communications post of the commander of the 62nd Army, both located on the bank of the Volga by the NKVD building, were completely undefended from the Volga side, even though the enemy was only 100-150 metres away. I pointed this out to the commander of the 13th Guards‘ Division, comrade Rodimtsev, and steps have been taken to strengthen the command post‘s defences.

Selivanovsky‘s report ends with accounts of a few mundane incidents from the life of a Soviet secret policeman in wartime: it was a harsh and cheerless round of arrests, interrogations, investigations and summary executions.

At around 10pm on September 14th, a group of enemy sub-machinegunners, having broken through to the area of Medveditskaya Street, captured the command post of the 8th Independent Company of the city’s Commandant Directorate, which was located in a tunnel. Around eighty men were taken prisoner when this command post was captured, and they are now being used in small groups to take ammunition to the German sub-machinegunners. One such group was recaptured by NKVD operatives in the area of the command post of the 13th Guards‘ Infantry Division, and four of the six men in the group were shot in front of the ranks as traitors to the Motherland. An investigation is under way.

On September 15th, a woman who spoke German was taken prisoner in the engagement outside the NKVD building. She said her name was Volodina, and she had actively participated in the engagement as a sub-machinegunner for the Germans. Since she was wounded she could not be interrogated, so Volodina was shot by our operatives.

The 62nd Army’s Special NKVD Section, responsible for patrolling the city, has set up task forces of men from the regular army to detain those acting suspiciously. At 11pm on September 15th, one of these task forces was fired on from a building in the area of the city market. A search of the building found five soldiers dressed in Red Army uniforms. All five were arrested, and an investigation is under way.

Between September 13th and 15th, the Defence Detachment of the 62nd Army’s Special Section detained 1218 soldiers, of whom 21 have been shot, 10 arrested, and the remainder sent back to their units.

Major Zhukov, commander of the signals regiment of the 399th Infantry Division, and Senior Political Officer Raspopov have been shot for cowardice: they had deserted the battlefield and abandoned their units.

It must surely have seemed to Selivanovsky that the fall of the city was inevitable, but he knew better than to say so. Others were foolish enough to voice such opinions out loud. One junior commissar wrote in a letter home that ‘Hitler will take Moscow this year and take it easily. Stalingrad will clearly belong to the Germans in a couple of days’ time.’ (That gloomy but realistic prognosis will certainly have cost the commissar his life, as his letter was intercepted by one of Selivanovsky’s watchful colleagues.)

The Germans, on the other hand, were in triumphant mood. Their vanguard was in the centre of the city and had advanced as far as the railway station, which they occupied. The loss of the rail terminus was a disaster for the Russians. The station was an advantageous spot from a tactical point of view,‘ said one Red Army man who fought there. ‘It gave cover over the whole of the town centre, and for the Germans was the quickest way to occupy the centre and push on through to the river crossing. That‘s why they put so much effort into capturing it.’ What is more, from the station the thick blue stripe of the Volga was plainly visible though the gaps between the buildings. Once they saw the river, the Germans sensed the battle was as good as over. German trucks came screeching to a halt in the city, soldiers piled out and began dancing drunkenly in the streets.

They were often in full view of Russians, who were too astonished by the sight of their opponents’ celebrations to shoot them. One German, although he was a little way behind the front line, got wind of the jubilation of his fellow soldiers and began to nurse hopes for the future.

The Reich flag has been flying over the centre since yesterday. The centre and the area round the railway station are in German hands. You cannot imagine how we felt about the news as we lay in the earth holes wrapped in our blankets. The cold north-east wind came whistling through the canvas strips of the tent. It was pouring with rain. By way of celebration we cobbled together a mixture of flour, water and some grease (intended for lubricating guns) and fried up some pancakes. We rounded off this delicious meal with tea and the last cigarettes. We could give a housewife a tip or two.

Just as we finished - I was on night duty - the Russians attacked and tried to cut off the approach road into town. The firing didn’t stop till early morning. Today it’s a stormy, cold autumn day, and we’re freezing even with our coats on, and are dreaming ahead of well-built winter quarters tucked into the earth, glowing little Hindenburg stoves, and a lot of letters from our beloved homeland.

THE 13TH GUARDS CROSS OVER

For the Russians, the capture of Mamayev Kurgan, 3 miles (4.8km) north of the city centre, was an even more catastrophic development than the loss of the railway station. This hill stood 335ft (102m) above the level of the river. From its rounded peak the Germans were able to survey the whole city and their artillery could rain fire on any boats that attempted to cross the river. They could not be allowed to hold the hill.

The only hope for stabilizing the front line inside the city rested with the reinforcements, who were coming across the river at a trickle during the night. The slow transfusion of new blood was just barely sufficient to keep the 62nd Army alive as a fighting force. The paucity of the reinforcements was due in part to the difficulties of crossing the river when it was under constant fire, and was partly a deliberate matter of policy. All available resources were now to be garnered for Zhukov’s great counter-attack. General Chuikov’s job (though Zhukov did not tell him so) was to keep the Germans busy until that time. He and his army were the bait in the big trap.

But the newcomers who came across the river from the east were often ill-prepared and under-equipped. The Soviet writer Viktor Nekrasov, who lived and fought through the hard September days, saw many of the green troops come over to the city from the left bank. It was a glorious and a tragic spectacle.

There were times when these reinforcements were really pathetic. They’d bring across the river - with great difficulty - say, twenty new soldiers: either old chaps of fifty or fifty-five, or youngsters of eighteen or nineteen. They would stand there on the shore, shivering with cold and fear. They’d be given warm clothing and then taken to the front line. By the time these newcomers reached this line, five or ten out of twenty had already been killed by German shells -for with those German flares over the Volga and our front lines, there was never complete darkness. But the peculiar thing about these chaps is that those among them who reached the front line very quickly became wonderfully hardened soldiers. Real frontoviks.

Fortunately for the Russians, they still had one trump card to play. The ace in their pack was the 13th Guards Division. This was the unit that Stalin had personally ordered into the attack on the evening of 13 September, and whose inadequately defended command post was noted by the beady-eyed Selivanovsky on the 15th. They entered the fray at the moment when the survival of the 62nd Army was balanced on a bayonet’s edge.

The little iliad of the 13th Guards began with a waterborne assault under heavy fire. Ten thousand men were crossing the river - a kind of D-Day in miniature - after a forced march through the Kalmuck steppe. One in ten of the guardsmen had no rifles, and those who were armed had little ammunition. But there was no question of waiting until they were properly kitted out. Every passing hour was an opportunity for the Germans. So the 13th Guards embarked straight away, their eyes and their boots still clogged with the dust of the Central Asian desert. Vasily Grossman, a special correspondent with the army’s Red Star newspaper, described the entry of the Guards into the city in an article published a few weeks after the event.

The men climbed aboard the barges, ferryboats and motor launches. ‘All set?’ ‘Full speed ahead,’ called the captains of the launches, and the grey, rippling band of water between the boats and the bank began to grow, to widen. A little wave lapped the prow of the boats. The barges bounced on the waves, and the men of the landbound rifle division began to worry that the enemy was everywhere - in the sky and on the far bank - and that they were going into the encounter without the reassuring solidity of the earth beneath their feet.

All heads turned in alarm, looking up at the sky. ‘He’s diving, the bastard,’ someone shouted. About fifty metres from the barge a tall, thin, blue-white column, all flaky at the top, suddenly rose up out of the water. The column collapsed, raining fat splashes on the men and washing over the deck. Then another column shot up rather closer, then a third. At the same time, the German mortars opened rapid fire on the division as it made its crossing. The mortars exploded on the surface of the water, and the Volga was covered with jagged, foaming wounds. Lumps of shrapnel thumped into the sides of the boats and the wounded cried out quietly - as if trying to hide the fact that they were wounded from their friends, from their enemies, from their own selves. And now rifle bullets were whistling across the water.

There was a terrible moment when a heavy mine struck the side of a small ferry. There was a flash of flame, and thick smoke covered the boat. You heard the sound of the explosion followed by another drawn-out noise that seemed to grow out of the booming sound of the first: it was the sound of men screaming. Thousands of men could see the heavy green steel helmets of other men trying to swim in the water amid the shards of wood. Twenty of the forty had died on the ferry, and it was a truly fearful moment when the guards division, strong as a Russian Hercules, knew that it could not help the remaining twenty wounded who were now slipping beneath the water.

The crossing continued through the night, and there has probably never been a time, while light and darkness have existed, that men have been so glad of the September gloom.

The motorized armada carrying the 13th Guards reached the far shore. The men clambered out of their boats and rushed straight into action, shooting as they clambered up the bank and into the dark maw of the city. Their commander, Alexander Rodimtsev, reported directly to Chuikov. Rodimtsev was tall and slim with grey hair sticking up like a bottle-brush on his narrow head. He looked like an intellectual, but he was a seasoned fighter, having experienced urban warfare as an ‘adviser‘ to the anti-Franco forces in the Spanish Civil War. He was adored by his men, and held in high esteem by superior commanders. But now Chuikov gave him orders that were on the verge of the impossible. He and his men were to take back both the summit of Mamayev Kurgan and the railway station, and they were to do it right away.

The task of taking back the station was delegated to Lieutenant Anton Dragan, commander of the 1st Battalion of the 42nd Regiment in Rodimtsev‘s division. On the evening of 15 September he received his orders. The station was so close that Dragan and his men were there within a few minutes, and Chuikov knew by the sound of gunfire that his orders were being carried out.

I had led my company to the railway station and began exchanging fire with the Germans, then battalion commander Chervyakov caught up with me, said Dragan. He came up close, and as he wiped his glasses he said to me: ‘You have got to cut them off, those fascists, and hold them back. Hang on as long as you can. Get some grenades in.’ I rounded up the company, and in the darkness we began to move round to the back of the station. It was night-time now, and there were noises of battle all around. Small groups of our forces dug themselves in inside half-ruined buildings.

I could tell that the main station building was in enemy hands. We cut across the railway track to the left-hand side. At the crossing stood a damaged tank, one of ours, along with about ten tankmen. We gathered near the station building and then went in expecting hand-to-hand combat.

It was a shock attack: grenade first, then a soldier right behind. The Germans made a run for it, shooting wildly in the dark. In the time it took for the Germans to realize that we were only one company we had set up strong defensive positions. And though they attacked from three sides several times in the course of the night, they did not manage to take back the station.

As dawn broke German dive-bombers began pouring hundreds of bombs on the station. And after the bombing came the artillery shells. The station building was in flames, walls were blown apart, iron buckled, but our people carried on fighting. By evening the Germans had still not managed to take the building. They finally realized that a frontal attack would get them nowhere, and so moved to surround us. Then we moved the fight to the square outside the station. There was a fierce fight around the fountain and along the railway track.

I remember one moment when the Germans had got behind us. They had gathered in a corner building on the square. We called this building the ‘nail factory‘, because our reconnaissance people had said there was a large stock of nails there. The enemy was planning to attack at our back, but we guessed what they had in mind and launched a counter-attack. We were aided by a mortar company, which had arrived at the station by this time. We didn‘t manage to take the nail factory in its entirety, but we drove them out of one of the workshops. They were still in the workshop next door.

Now the fighting continued inside the building. Our company strength was almost used up. But it was not just our company: the whole battalion was now in an extremely difficult position. The Germans were pushing us back from three sides. We were running low on ammunition, and there was no question of eating or sleeping. But worst of all was the thirst. To get water, in the first instance for the machine guns, we fired at drainpipes to see if any water came out.

This battle had now entered its third day, but showed no sign of ending. Inside the nail factory, exhausted soldiers from the two armies tiptoed round each other, probing for some tiny tactical advantage, any fleeting opportunity to kill.

Plate 1. The cult of Stalin reached new peaks in the course of the war. He was routinely described in the press as ‘the genius organizer of our victories‘ and ‘the great captain of the Soviet people‘. He became a genuinely popular leader, the very embodiment of the Russian war effort.

Plate 2. Georgy Zhukov, Stalin‘s best general, was as ruthless as he was gifted. ‘If we come to a minefield, our infantry attacks exactly as if it were not there,‘ he said. ‘The losses we consider equal to those we would have had from guns if the Germans had chosen to defend the area.‘

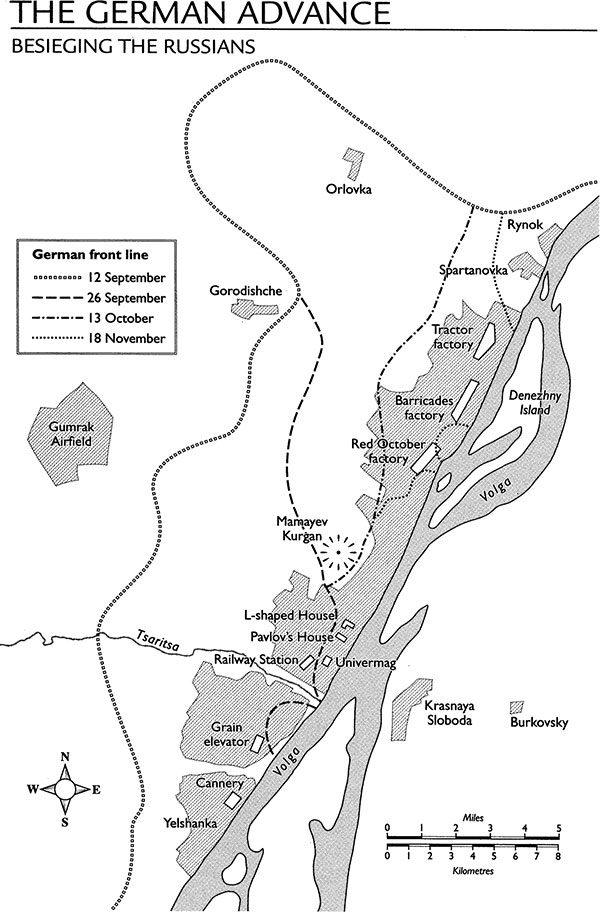

Plate 3. Hitler with his generals on the eve of Operation Blue. Friedrich Paulus, the recently appointed chief of the Sixth Army, is second from the right. Paulus was a gifted staff officer, but he had never commanded an army in the field. He did, however, have total belief in Hitler‘s genius.

Plate 4. German tanks made rapid progress in the summer of 1942, but it was not a comfortable ride for the tankmen. ‘There is a fierce wind blowing that makes us all look like dusty millers on the sandy, unmade roads,‘ wrote one driver, ‘And nothing but steppeland on every side. ’

Plate 5. This playful sculpture stood outside Stalingrad‘s railway station, which can be seen burning in the background. In the month after the initial bombing of the city desperate hand-to-hand fighting took place here, under the eyes of the dancing children and the snapping crocodile.

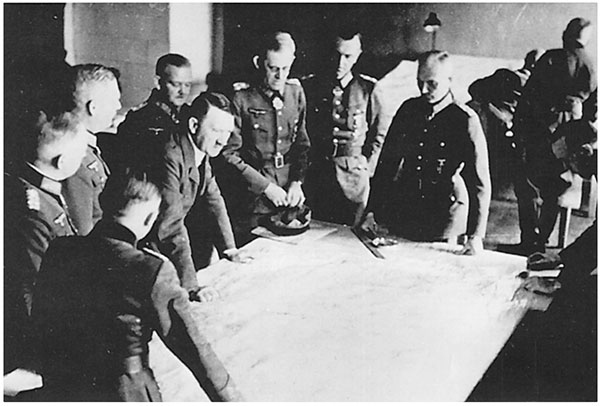

Plate 6. In May 1942, German gunners accidentally fired on Wolfman von Richthofen‘s plane. He later sent a note to their commander: ‘While it is a delight to see the fighting spirit of the German troops against aircraft, may I ask that they direct their fighting spirit against the Red Air Force?‘

Plate 7. Many Germans thought the coming battle would be easy. ‘We’ve crossed the Don and are now positioned a short distance from Stalingrad,‘ wrote one soldier. ‘It has been hot, but at night it gets a little colder each day. But soon we will be standing on the banks of the Volga.‘

Plate 8. This picture of the grain elevator was probably taken at the end of September, after it had at last fallen to the Germans. Massive damage had been inflicted on the corner at the south-west, which was the German direction of attack. The Volga is no more than a mile away.

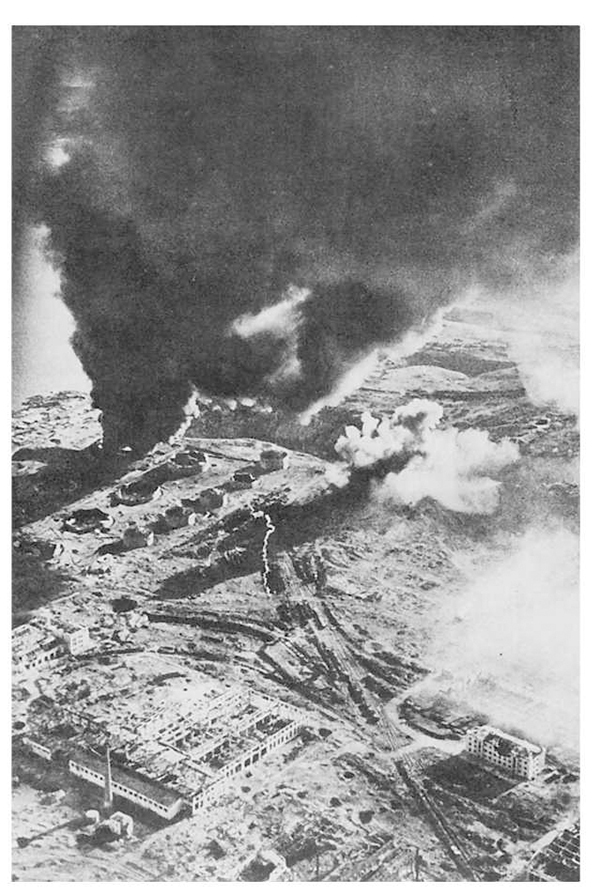

Plate 9. In the days after the air raid on Stalingrad, thick plumes of poisonous smoke rose from burning oil tanks and blocked out the sun. The fires could be seen from 40 miles (65km) away. But the smoke was a blessing it hid troop movements within the city from German eyes.

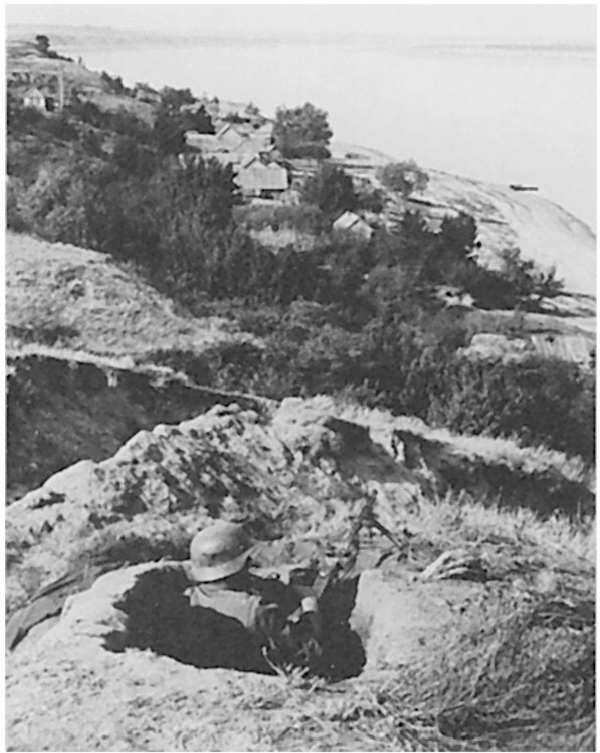

Plate 10. A German soldier sits in a cosy foxhole on high ground north of Stalingrad. His gun is trained on the Volga. The fact that the enemy occupied the riverhank at this point caused the Russians endless problems. It was almost nigh impossible to bring over reinforcements in daylight hours.

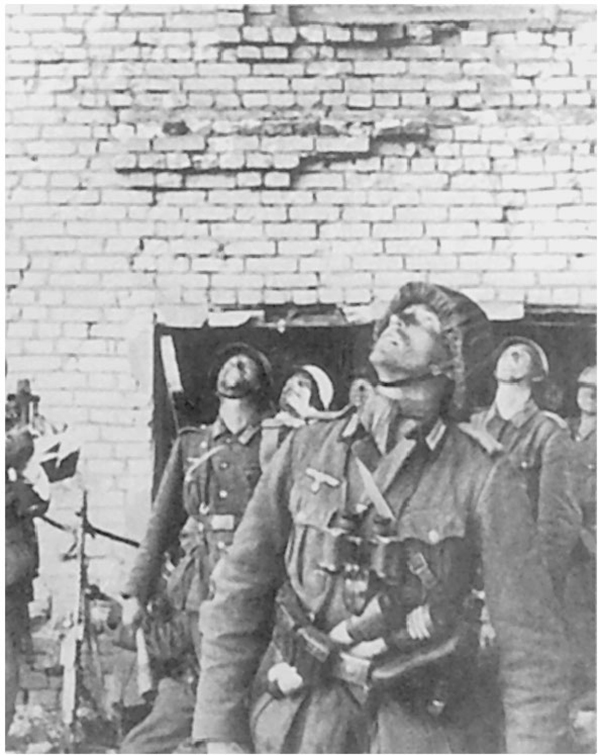

Plate 11. A band of Germans, adrift in the factory district, nervously scan the sky as a plane flies overhead. In the early days the Luftwaffe had control of the air, but by the end of October any passing plane was as likely to be a Russian fighter-bomber as a friendly Junkers.

Plate 12. General Vasily Chuikov (second from the left) holds a meeting in his cramped bunker. His HQ was at times within three hundred yards of the German front line. The grey-haired man on the right is Alexander Rodimtsev, commander of the celebrated 13th Guards Division.

Plate 13. Heavily armed Russian infantrymen share a loaf in some ruins. The man on guard has a Degtyarev machinegun - recognizable by its flat, frying-pan magazine. The two men on the left carry the ubiquitous and deadly Schpagin tommygun, while the man on the right has a long anti-tank rifle.

Plate 14. Russian artillery takes up position inside a factory workshop. (The furnaces were a good place to take cover; said one Russian soldier. ‘Get inside there and the shrapnel can’t touch you. And you’re safe even if the bombs bring the walls and ceilings down on top of you. ’

Plate 15. ‘Stalingrad is no longer a city, ’ wrote one German. ‘By day it is a cloud of burning blinding smoke. When night arrives, the dogs plunge into the Volga and swim desperately to the other bank. Animals flee this hell; the hardest stones cannot bear it for long only men endure.‘

The fighting in the nail factory would go quiet for a time then break out again even more fiercely, continued Dragan. In short skirmishes knives, spades and rifle-butts came in handy. Around daybreak, the Germans began to bring up reserves and company and they moved against us. It became difficult to hold them off. They were on three sides of us. I sent an urgent report on the situation to Senior Lieutenant Fedoseyev. The third rifle company, commanded by Junior Lieutenant Koleganov, was sent to help us out. On its way to us the company came under a storm of fire, it was attacked several times. But the tall, wiry figure of Koleganov got through with his company. His army greatcoat was covered in brickdust when he said laconically: ‘Twenty men reporting/ In his report back to battalion headquarters this officer wrote: ‘Arrived at nail factory. Situation difficult, but while I am alive no bastard will get through‘.

Fierce fighting went on deep into the night. Small groups of German machinegunners and snipers began to get round behind us. They hid in attics, in ruins and in sewer pipes and hunted us from there.

Now began an odd game of leapfrog: Dragan was ordered to assemble a group of machinegunners who would try to get behind the Germans - who had already got behind the Russians - inside the nail factory. Dragan gathered a team of volunteers, but did not go with them on the mission. But perhaps he envied the men he sent out, because they at least got something to eat:

Each man received a five-day supply of food and ammunition, along with detailed instructions on what to do. Soon the German defence was in a state of alarm. It seemed they could not understand who had just blown up the lorry which had just brought them ammunition, or who had put their machinegun crew and their artillery auxiliaries out of action.

From morning till midday clouds of enemy planes hung over the city. Some of them would break away from the group and dive, then strafe the streets and the ruins with a hail of bullets. On the night of the 18th the Nazis blew up the wall separating our room from the rest of the nail factory, and started lobbing grenades through. Our guardsmen tried to throw the grenades back through the windows.

Dragan’s men held out for another 24 hours inside the building they now shared with the Germans. On the 20th they received word from a civilian that the Germans were preparing a tank assault. The attack came on the morning of 21 September - the darkest day‘. Dragan’s battalion was pushed right back from the station square. The men retreated in groups down the street that led towards the Volga, less than a mile away, but the soldiers would crawl back from their positions only when the ground was burning beneath them and their clothes were beginning to smoulder.‘

By the afternoon of the 21st, separate bands of Russians were fighting inside the Univermag department store building, a quarter of a mile east of the railway station. (This building was destined to play its own part in the battle some months later, at the very end of the drama.) Dragan himself was in a building one street away to the right, no more than 600 yards (550m) from the river. The supply of ammunition was now so low that the men in Dragan’s group had pulled bricks from the walls and laid them in rows, ready to throw at the Germans.

There were now only 12 men left with Dragan, but they held out in this new redoubt for five days. One young officer lost his nerve and sneaked away at night. He was sure that all his comrades were going to be killed, so when he reached HQ, having floated across the Volga on a log, he announced that he personally had buried Dragan. So now no one at headquarters knew that the 1st battalion of the 42nd regiment was still in action.

The Germans were still well aware of it, though, and Dragan thought it would be a good thing to rub their noses in it.

We decided to hang out a red flag on the building, so the Nazis wouldn‘t think we had given up the fight. But we had no red material. What could we do? One of the wounded heard of the plan and took off his bloody vest. He wiped it on his bleeding wounds and handed it to me. The Nazis called out at us through loudspeakers: ‘Rus! Give up! You are going to die anyway!‘ At that moment our red flag was raised over the building. My radio operator Kozhushko shouted back: ‘Bark all you want, you scurvy dogs. We still have a long time to live!‘

A German tank appeared at the rear of the building, and Dragan sent an anti-tank man named Berdyshev to deal with it. Berdyshev took the last three anti-tank shells with him but did not manage to fire them because he was grabbed by some Germans and dragged out through a window as he got into position. An hour later, the Germans launched an attack at exactly the point where Dragan had put his last emergency machinegun. Dragan guessed that the Germans had asked Berdyshev to tell them the weakest point in the defence, and that he had told them the opposite. This guess was confirmed in the afternoon when the Germans led Berdyshev on to a hillock of rubble in sight of the Russians and executed him with a bullet to the head.

The finale came later that day: another attack with tanks. The Russians knew their lives were at an end. They fired off the last of their ammunition as one man scratched a message on the wall: ‘Rodimtsev‘s guardsmen fought and died for their country here.‘ Tank shells slammed into the building at point-blank range, and it collapsed on top of the defenders.

The Russians were buried in the rubble, but not all of them were dead. Some time after dark Dragan gained consciousness to find Kozhushko tugging him from the wreckage: ‘You‘re alive!‘ The survivors were now stranded behind enemy lines. The Germans had advanced past them, but were still a few hundred yards short of the Volga. So Dragan and the handful of men he had left crept through the streets towards the river and their own lines. They killed two sentries along the way. They slipped into the cold water and drifted across to the safety of the left bank.

Towards morning we washed up on a sandy spit, where there was an anti-aircraft battery. The artillerymen looked in amazement at our rags and our hollow, unshaven faces. We were barely recognizable as fellow soldiers. They fed us with some astonishingly tasty crusts of bread and fish soup - I have never eaten anything more delicious in my life. It was the first food we had seen in three days. Later that day, the artillerymen sent us on to a field hospital.

ON MAMAYEV KURGAN

While Dragan’s men fought a losing battle for the station, a larger detachment of the 13th Guards was headed for Mamayev Kurgan. Their commander was Colonel Ivan Yelin. When he arrived at Height 102, as it was designated on the military maps of both sides, he saw a small chink in the Germans’ armour.

The Germans were slow to organize a system of fire between their different units. The infantry and the artillery were not operating in tandem. That fact meant that we of the 13th Guards had some success at first. The 13th Division arrived just in time. A day, or even twelve hours later, and the Germans would have entrenched themselves in the centre of the city and we would never have made it across the river.

Constant pressure from the guards kept the Germans off balance, and made it impossible for them to set up artillery on the peak of the hill. This was a triumph in itself, though it cost the guards all their available ammunition and a full third of their entire fighting force: 3,000 men died in the first battle for the kurgan. But according to the cruel economy of those days, the sacrifice of so many lives was worth it because it meant reinforcements and supplies still had some chance of making it across the river. It kept the Russians in the game. Some of the new reinforcements were themselves destined for the kurgan. Nikolai Maznitsa of the 95 th Rifle Division arrived there on 19 September, and almost became a witness at his own funeral.

An attack began in the morning and lasted 48 hours. The enemy was moving inexorably towards the summit in six files. At times it seemed to us that they were invincible. But the sixth file did not hold out under our fire, and we rushed into the attack, and dug in on a new line to prepare for the next advance. Then came the planes once again, along with the artillery fire, the iron columns of soldiers, the renewed attacks.

Most of the German soldiers appeared to be drunk, and threw themselves in a frenzy at the summit. After each round of bombing there would be a moment of dead silence - and that was when you would get afraid. But then the hill would come alive again like a volcano, and we would crawl out of the shell holes and put our machineguns to work. The barrels of the guns were red-hot, and the water boiled inside them. Our men attacked without waiting for orders. I don‘t know of a single case where someone committed an act of cowardice. It was mass heroism.

We lost many men as a result of direct hits on shell-holes. On September 23rd I was buried in my foxhole during an attack, and was unconscious under the earth for several hours. When they dug me out they took my documents away as evidence of my death, and they were about to bury me in a different hole when a bomb blast threw me several metres and somehow brought me round from the concussion. I re-took command of my company that same day.

The slopes of the kurgan were completely covered in corpses. In some places you had to move two or three bodies aside to lie down. They quickly began to decompose, and the stench was appalling, but you just had to lie down and pay no attention.

The dead were buried, if at all, where they fell. But sometimes, if there was time, they were put in big shell holes - as nearly happened to me. It wasn‘t always possible to report the names of the dead, and sometimes the courier with the casualty report was himself killed along the way.

Sometimes it seemed that we were all condemned to death - but we despised death all the same, and wanted only to sell our lives as dearly as we could.

Maznitsa‘s division fought on the hill for 11 days, and was then relieved by the 284th Rifle Division, a fresh unit from Siberia. Captain Viktor Popov was among them.

At the end of September our HQ moved to the west bank of the river. It was set up in the big concrete pipes that carried waste water to the Volga. Here the cliffs rise about 50 metres above the river, and are about 800 metres from the foot of Mamayev Kurgan. Our main positions on the right flank were the southern and western slopes of the kurgan, and on the left flank the building of the Metiz factory, where the railway lines and tram lines ran from the south to the north of the city.

The highest point of the kurgan was crowned with two huge concrete cisterns, which were the main water reservoir for the city. These cisterns had no water in them, and had been that way since August.

The empty cisterns were, however, a real prize. They were a ready-made bunker right at the most strategically important point in the city. Both armies wanted to possess the cisterns, and so they played at dog-in-the-manger, trying to prevent the other side from getting any protection from them. The Germans won out - for a while at least.

The German attacks were vicious, especially on the right-hand side of Mamayev Kurgan, continued Popov. Here the Germans made use of tanks and self-propelled guns. They knew that from the top they would be able to fire on our gun emplacements over open sights. The Germans attacked without success for a long time, but eventually our battalion on the right flank had to move back, and took up a new position at the foot of the kurgan.

The battle for the kurgan reached a murderous stalemate that was not broken for months. The Germans held on to the western slope, and the Russians never quite left the eastern one. At nights the Russians would creep forward a few metres, literally clawing back the hill, repossessing it by tiny increments. In the daytime, soldiers fought separate battles in ones and twos, like gladiators in the ring. The opposing sides were close enough to each other to thrash it out using grenades, sharpened spades and bayonets. Neither side could claim undisputed ownership of the summit and its precious cisterns. And the constant bombing and shelling warmed the punished earth to the extent that no snow settled on the kurgan throughout the long cold winter of 1942.

FIGHTING IN THE RUBBLE

By the end of September the Germans had wrested most of the city centre from Russian control, and in several places had gained a foothold on the riverside. In the sector defended by the 13th Guards, the territory held by the Russians was little more than a ribbon of bombed-out wasteland barely a quarter of a mile (400m) deep. If the Germans, who had travelled hundreds of miles to get this far, could just take this last little strip of land, then Stalingrad would be theirs. But the fighting in Stalingrad was unlike anything any of the combatants - the Germans or the Russians - had experienced before. General Hans Doerr described the nature of the fighting inside the city, where a hyperinflationary price had to be paid for every gain.

The time for conducting large-scale operations was gone forever. From the wide expanses of steppe-land the war moved to the jagged gullies of the Volga hills with their copses and ravines, into the factory area of Stalingrad, spread out over uneven, pitted, rugged country, covered with iron, concrete and stone buildings. The mile as a measure of distance was replaced by the yard. Headquarters‘ map was the map of the city.

For every house, workshop, water tower, railway embankment, wall, cellar and every pile of ruins a bitter battle was waged - one without equal even in the First World War with its great expenditure of munitions. The distance between the enemy’s arms and ours was as small as it could possibly be. Despite the concentrated air and artillery power, it was impossible to break out of the area of close fighting. The Russians surpassed the Germans in their use of the terrain and in camouflage, and were more experienced in barricade warfare for individual buildings.

Doerr’s grudging tribute to the Russians’ fighting skills was right in all but one respect. It was not so much experience that told for the Russians, but verve and imagination. Before Stalingrad, the Russians knew no more about urban warfare than their opponents. But the fact that they had their backs to the wall - or rather to the water - and that they had to make the very best of the small resources available to them, meant Russian commanders were forced to come up with a new way of defending the town. They needed a method that made the most of their strengths.

The first and most vital element of the Russian tactic was to stay close to the enemy. Every Russian strived never to be further than a grenade’s throw from a German. This meant the enemy was constantly unnerved, and it also neutralized the Germans’ single greatest advantage - air power - because the Luftwaffe could not bomb the Russian vanguard without risking dropping their payload on their own men. The Germans tried to counter this by sending up white signal flares to show the position of their own front line, but the Russians took to sending up flares of their own to confuse the enemy pilots. Whenever the Germans changed the signal, the Russians soon caught on and spoiled it.

Bombing was in any case an irrelevance. After August, all the bombs ever did was reconfigure the rubble, resculpt the desolate cityscape. The Russians would tuck themselves away in basements while the raids went on, then emerge to continue the battle on the same blasted terrain. Aerial bombardment merely created new hiding places and fresh opportunities.

The total destruction of the city had another unfortunate effect from the German point of view. It rendered much of the city all but impassable to tanks. The German method right from the start of the war was to send a tank or two in first to blast the opposition’s strongpoints, then to have the infantry come up in their wake, mopping up the enemy and digging in at a new forward line. But the Russians would hide in buildings and allow the German tanks and infantry to advance past them, then emerge and spray the infantry with machinegun fire from behind (this was precisely the modus operandi that Willi Hoffman found so unfair). The tanks would then have to back up to escape the ambush. Even if they could turn their gun turrets around, their engine grilles would be exposed and vulnerable to attack with anti-tank guns.

Molotov cocktails were also used to great effect against tanks. The Russian tactic was to hurl them down from the upper storeys of buildings. The Russians, incidentally, never used the term ‘Molotov cocktails’, which was a Western coinage; they always called them by the prosaic and long-winded expression ‘bottles of inflammable liquid’. But they produced these simple weapons on an industrial scale and to a variety of designs. Some contained chemical mixes that ignited on contact with the air when the bottle broke; some had percussive caps that set light to the liquid in the bottle on impact; some were entirely homemade - vodka bottle, petrol from a can, rag stuffed in the top and lit with a match - and no less deadly for that.

A favoured Russian technique in Stalingrad, one at which the Red Army became very adept, was to lure the Germans into the narrow canyon of a street, then to get behind them by moving along the sewers (dry now that the town had ceased to function) or through the attics of buildings. Basements were also used for this purpose, and the Russians often went to the trouble of breaking down the connecting walls between buildings at cellar level in anticipation of an attack. This allowed them to move swiftly and invisibly to the rear of the enemy even as the German tanks rolled forwards (with the infantry creeping along behind) at street level. The Germans were constantly amazed and dismayed at how the Russians popped up in unexpected places above and behind them. They called this unhappy experience Rattenkrieg - rat war‘ - and they never got the hang of practising it themselves. And so the battle became a constant game of cat-and-mouse in the wreckage of the town, a kind of hide-and-seek in which the loser got a bullet to the forehead or a bayonet to the ribs.

PAVLOV‘S HOUSE

The Russians’ clever defensive tactics were complemented by offensive methods that were just as troubling to the Germans. Soviet commanders in the city quickly saw that frontal assaults with large numbers of troops were too expensive in terms of manpower, and often failed in any case. So they evolved a method in which small heavily armed ‘shock groups’ would take houses one at a time. These units were broken down into three sections. The first group would carry out the initial storming of a house, usually using grenades; the moment they were inside, the second group would follow and mop up, or set up a defence perimeter to prevent immediate counterattacks; the third group was a reserve, which could also be used for covering fire. Once a house was taken, the storm group would set up an ‘active defence’ - which meant fortifying it in such a way that it became a link in the general defence of the sector, a small and integral addition to the sum of Soviet territory. Shock groups were equipped to withstand siege for long periods without significant backup. They took several days’ food with them whenever they carried out an attack.

In the annals of Stalingrad, the most celebrated instance of active defence is the long siege of a four-storey apartment block known as ‘Pavlov‘s House‘. In this building a small group of Russians held out for two months under constant attack. The house was taken without a fight in the last week of September by four men under the command of a Sergeant Yakov Pavlov, a man who turned out to have a real talent for stubborn defence. ‘He was quite a short fellow with a thin face,‘ recalled his commanding officer. ‘He used to wear a rather dandyish fur cap in the Kuban style, and his tunic was faded and covered with dust.‘ As soon as the four men were settled into the building, Pavlov sent one of them back to report. The scout told HQ that ‘all was well in Pavlov‘s house,‘ - a remark that was overheard by an army newspaper reporter. The journalist published an article, headlined ‘The House of Sergeant Pavlov‘. After that, the designation Pavlov‘s House became common currency in the 62nd Army, even among men who had no idea why it was so called.

I could see why our commanders had felt that this building was so significant, said one of the men who fought with Pavlov. From the fourth floor you could observe not only the whole of Ninth of January Square, but also all the ruins beyond. It stuck out into the German defences. To the left and to the right of us were Germans. Only to the rear of us, towards the Mill, was there an area that was occupied by our men, and that too was under constant fire.

In other words, the long oblong of Pavlov‘s House protruded into German-occupied territory like a headland into the sea. (For radio purposes, the Russians gave the house the appropriate code name mayak - ‘lighthouse’). Not only could Pavlov and his comrades watch the Germans‘ every move, but it was also relatively easy for them to report back. The Mill mentioned by Pavlov‘s comrade-in-arms was a large brick grain store about 300 yards (275m) directly behind the house and about the same distance from the river. It was an important command post, and a staging post for troops coming over from the far bank. There was a constant dialogue between Pavlov‘s House and the Mill, so Pavlov‘s vital observations were quickly transmitted back to HQ. As the siege developed a long trench was dug between the two buildings to make the process less perilous for the runners.

The Mill was as strong as a castle, said Georgy Potansky of the 32nd Regiment of the 13th Guards. But neither the enemy air force nor our own bombed the area around Pavlov’s House, the Mill and Ninth of January Square because the lines were too close to each other. The only thing that saved us from starving was the fact that there were large quantities of grain in the basement of the Mill. We slept on it, and we fed ourselves with it. We often had to grab our guns and grenades and beat off German attacks. Many of our soldiers were put out of commission - some killed, some wounded. The wounded often died because we did not know how to give them first aid, how to bind their wounds. No one had taught us.

At Pavlov’s House the danger was ten times greater. The Russians sent reinforcements up from the Mill to create a ‘garrison’ in the block. One of the newcomers was Lieutenant Ivan Afanasyev, who outranked Pavlov and so took command of the incipient siege.

I told Pavlov my name and why I was there, recalled Afanasyev. ‘Excellent,’ he said.‘ We could use a bit of help. This is a big old house and there is just the four of us. The more, the merrier.’ Pavlov led me down a narrow corridor and into the basement. A kerosene lamp was burning. In the middle of the room stood a table, like a carpenter’s bench. On it lay a box of shells and about a dozen grenades. In one comer there was an iron bedstead, on which there was an untidy pile of blankets and pillows. On the floor there were lots of spent cartridges.

We selected the best spots for our machineguns and for our anti-tank gun. As soon as we set up the guns, all the fighters began to block up the windows and doors with bricks and boxes of sand. The basement was divided into four sections which were separated by thick supporting walls. Up above, the attic windows commanded a wide field of fire. The men who built this house probably never dreamed that their work would be judged from a military standpoint.

The Germans soon spotted the activity in the house, and realized they had made a tactical error by letting the Russians take it. Repeated attacks were made across the square. They came swarming over like bees from a rattled hive said one soldier. As in the wider battle for the city, the defenders were kept going by a small but steady influx of men and materiel.