5

URAN -THE COUNTER-ATTACK

Operation Uranus, the long-awaited counterstrike, was set in motion at dawn on 19 November. The Russian word uran - ‘Uranus‘ - is reminiscent of the word uragan - ‘hurricane‘, and the counter-attack began with a storm of artillery fire the like of which had never been seen on the eastern front. Three and a half thousand big guns and mortars, the ‘gods of war‘ as the Russians liked to call them, roared without ceasing for 80 minutes. Above their thunder the whistle and screech of katyusha rockets could be heard as they arched across the sky like a furious meteor shower. High-explosive shells fell so thickly on the frozen steppe that they created a solid wall of smoke, flame, noise and flying earth.

The Russian barrage was directed in such a way that this wall of fire crept remorselessly forwards. Ahead of it, the ground was covered with a level blanket of snow. Behind it, the earth was dark and uneven like a newly ploughed field. The men of the Romanian Third Army, who were in the front line of defence, cowered and trembled in their trenches. They watched the terrain change from white to black as the barrage moved towards them, and they waited to die.

Theodor Plievier, in his novel Stalingrad, described how it felt to be a German soldier of the line at this moment.

Had there been a forest there, the trees would have been mowed down like grass under the strokes of a mighty scythe. But there was no forest; it was flat, treeless terrain and looked now like the surface of a lake beaten by plump raindrops. Only here it was not rain but glowing metal tearing into the earth, and what was thrown up was not spray but sand and mud; what remained were yawning shell holes. Where snow had lain, the fierce heat laid bare the scarred grass, and a moment later grass and topsoil as well disappeared. A landscape like the mountains of the moon was created; it drew closer and closer to the German lines and took over a terrain where there was not only sand and mud, but bunkers and corridors, and pillboxes with built-in battery positions, machine-gun nests, and mortars; a terrain where munitions dumps, command posts with map tables, stables, bedrooms and living rooms were embedded under heavy layers of soil, and where the crowded German crews fought - eyes glued to sights, hands on firing levers, dragging up shells and mortar ammunition. The muzzles of the guns flashed; shell after shell shot up out of the mortars. Brown smoke rolled over the earthworks. Where machine guns and riflemen began firing, it was a sign of incipient panic, for there were as yet no recognizable targets.

Along the whole front death stalked the German positions. Foreground and background were a billowing mass of smoke, dust, and fiery vapours bursting toward the sky and sinking down again. A hill spitting fire appeared -a heavy battery had blown up in the shape of an inverted pyramid. The dark fragments in the glare were pieces of metal and bodies. Black, cloudy masses spurted upward. Darts of fire, balls of smoke. Beams and props clattering to earth. A horse falling from the sky, legs and hoofs pointed upward. A barbed-wire entanglement with posts attached floated through the air. An infantry regiment with its divisional artillery was blown up, fell back to earth, and was again thrown up, turned over, and reduced to dust.

The human figures that bounded out of a crater and moved over the ground like dry leaves swept before the wind, that stumbled over one another, fell and remained on the ground or stood up again, struggled on a little farther, only to fall again and run again - these figures were no longer members of a regiment; they were‘ chaff’. The tall lieutenant who emerged from the zone of smoke staggering and gesticulating like a drunkard, and suddenly breaking out into peals of laughter - this was no platoon commander; it was a madman. A figure crawled over the snow like a worm, leaving a trail of blood behind him, and finally tumbled into a hollow.

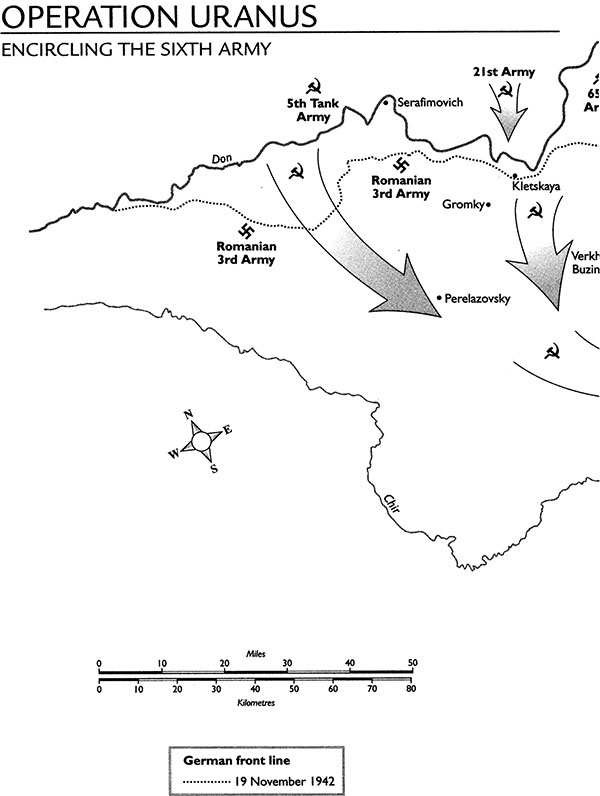

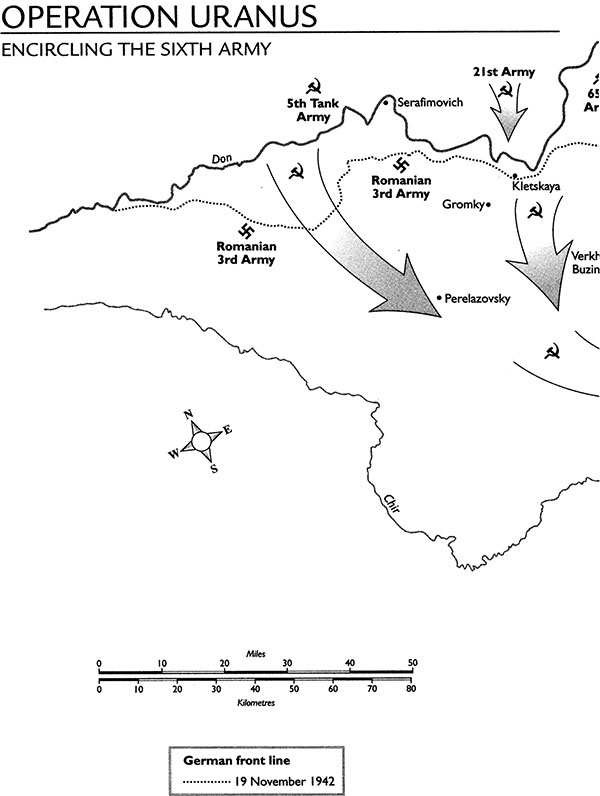

This first blow of the offensive was directed against the northern flank of the Axis forces. Here, where the Don flows roughly west to east, the Russians held two bridgeheads on the southern side of the river: one was at Serafimovich, the other 25 miles (40km) further east at Kletskaya. These two patches of land were the starting point of the attack. Launching the offensive from the largely German-occupied side of the river meant that the Russians did not have to cross the Don in the first hours of the counterstrike. And the fact that the Russians went in two-fisted confused the enemy - where was the main blow falling? Which way should reinforcements be sent? Each blow looked as threatening as the other.

What is more, both punches fell largely on the Romanians. The 170,000 soldiers of the Romanian Third Army were in an unenviable position. Their strategic value to Hitler lay in the fact that they could be used for the donkeywork of holding the flanks while German soldiers did the real job of fighting. But the Romanians did not have the tools or the manpower to perform even this menial task. Their ten divisions were spread over a front of 100 miles (160km), which made them far too feeble an obstacle in the open steppe: the defences were paper thin, and their anti-tank guns were so obsolete they were practically useless. Moreover, most Romanian troops felt no sense of commitment to the battle for Stalingrad anyway. Their only political interest in the war against Stalin was in taking back the province of Bessarabia, on the east bank of the river Dniestr, which they saw as historically and culturally Romanian territory. They could not understand how they were serving their country by freezing to death on the wind-blown Russian steppe. Most galling of all for the Romanian rank and file, they were treated with disdain by their own officers - and they were viewed with unconcealed contempt by their German allies, for whom they were only one step up the racial ladder from the Slavs.

These demoralized, unhappy, badly equipped, homesick men were no match for resurgent cohorts of the Red Army. As soon as the opening artillery barrage ceased, Russian tanks came trundling out of the mist towards the dazed and deafened survivors of General Dumitrescu’s Third Army. About a thousand T-34s poured through the gap at Serafimovich, and almost as many rushed into the breach at Kletskaya. Riding on the back of tanks, or plodding along in their wake, were the teeming masses of the Russian infantry - about half a million men in total. And then there was the Russian cavalry. They galloped into battle holding their swords aloft, a curiously anachronistic sight alongside the steel hardware of tanks and self-propelled guns. These riders did what cavalrymen everywhere have done to shattering effect since medieval times: they hacked the enemy’s footsoldiers to pieces. Pulat Ganiyev was one of the Soviet horsemen. He was an Uzbek, from the ancient Muslim city of Samarkand on the Silk Road, and he gave his account in the manner of a tale from The Arabian Nights. Pulat himself is the Sinbad-like hero of his own story.

The cavalry of Pulat Ganiyev was riding out of the northwest, when suddenly it came upon the Germans, wrote Ganiyev, after the war. Pulat and his fellows charged the German column and cut into them. Some of us were on horses, others were on wheels. It was a cruel battle. Not only were there Germans, but also Italians, Hungarians and Romanians. We fought hand to hand. Pulat and his fellows used their swords, their bayonets and their knives. Blades flashed in the frosty air and down went the enemy. The day was cold and foggy too. It took a strong spirit and a strong body to win through.

OF MICE AND MEN

German commanders behind the front line could tell by the sheer din of the Russian artillery that something ominous and spectacular was under way. Berlin was informed, and Hitler was told the ‘alarming news’ at the Wolf’s Lair. He nodded sagely and declared that he had long foreseen this development. From 1,200 miles (2,000km) away, he decided to take control of the battlefield. After taking a look at the situation map, he issued orders to activate the 48th Panzer Corps under General Ferdinand Heim. The 48th Panzer had been sitting behind the Romanians for months. The unit had been given no fuel, because all available resources went to fighting units, and so the Panzers had gone into hibernation. Pits were dug and lined with straw, and the tanks had been driven into these burrows to protect their engines from the Russian frost. Unfortunately, field mice had snuggled down in the straw too, where they nibbled into the insulation of the tanks’ wiring. When the men of the 48th Panzer rushed to man their tanks, like fighter pilots scrambling for a dogfight, they found that many of the machines wouldn’t start because the mice had eaten through ignition cables. In some cases the gun turrets didn’t work. One or two tanks short-circuited and burst into flames.

Less than half of Heim’s 102 tanks turned out to be battleworthy - or even roadworthy. But this much reduced yet still formidable force set out north-east towards Kletskaya, as ordered by Hitler. They were already on their way when new orders came. Hitler was suddenly worried that the more dangerous prong of the attack was the one spearheaded by the Russian Fifth Tank Army, heading south from Serafimovich. He sent new instructions to Heim via Berlin: 48th Panzer was to make a sharp left turn and engage Romanenko’s Fifth Tank. Heim’s men did as they were told, but somewhere along the way Heim lost touch with the Romanian tank units that were accompanying him. When Heim eventually encountered Russian tanks, the only Romanians he could see were fleeing infantrymen. Nevertheless he joined battle, and destroyed a couple of dozen T-34s with his force of 42 machines. He then withdrew before he was caught between the two streams of Soviet armour flowing to the left and right.

Heim‘s engagement was a gallant and businesslike piece of soldiery. He had made the best of a bad job and inflicted damage on the enemy. But the Führer did not see it that way. He interpreted the withdrawal of the 48th Tank as an act of cowardice, and had Heim arrested in the field. The unfortunate general was flown back to Germany, court-martialled, and thrown into jail. Between them, Hitler‘s temper and Russian mice had destroyed a capable commander at the very moment when his skills were most sorely needed in battle.

While Heim was careering across the steppe looking for someone to fight, General Paulus was trying to establish the extent of the Russian offensive. A staff officer sent to make an assessment found himself in the midst of a rout before he got anywhere near the front line. Thousands of Romanians were fleeing south, away from the flashing blades and the roaming T-34s of the Russian strike force.

An unrestrained, disorderly crowd flows past me. Soldiers trudging along in groups or alone. A field kitchen heads towards us. Wounded soldiers hang off it, as it is dragged along by horses. A few more field kitchens, and then three small trucks. They are also packed to the roof with men. Unhappy, dumbfounded faces. Men looking like ghosts cling to the sides with hooked fingers. They trudge along, moving their legs robotically. Their tall sheepskin hats are pulled down to the bridge of their noses, the collars of their greatcoats are turned up to cover their mouths, so all you can see is a band of their unshaven faces, which they try to hide from the burning-cold wind. Almost all of them, apart from a few yowling drunks, are marching in silence. Nobody reacts when I try to speak to them. I am glad when this nightmare passes by me, but a little further on I encounter another group. And once again this barely moving trail of ghosts winds past, some with open eyes, others with eyes shut. They don‘t care where this road leads. They are running away from war and want only to save their own lives. Nothing else means a thing. A Romanian colonel tells me frankly, as he straightens the pus-soaked bandage on his head: "You’ll get nothing more out of my soldiers. They are not obeying any of my commands.’

Another German officer saw a similar sight: frightened, shell-shocked Romanians who in the space of an hour had lost all their will to wage war. He felt little pity - only anger at his feckless allies.

They all had an expression of horror which seemed to be frozen on their faces. You would have thought the very devil was snapping at their heels. They had thrown everything away as they made their escape. And as they ran for it they added to the number of withdrawing troops, which was huge enough without them. It all added up to a picture which was reminiscent of the retreat of Napoleon from Moscow.

As in 1812, the avenging Russians were not far behind. Petr Zhulyev was with an artillery battery of the 21st Army, which had pummelled the Romanian line at Kletskaya from the far bank of the Don. As soon as the bombardment was over, it was time to pack up and move forward. But Zhulyev advanced a little further than was good for him.

After the artillery barrage our forces headed towards the river crossing. We had to climb the steep right bank. Thousands of soldiers clambered to the top, ripping their fingernails and cutting their palms on the jagged, frost-hardened ground. It was hard to imagine how the expanse of earth ahead of us, encrusted with ice and churned up by bombs and shells, could be peaceful or fruitful ever again. But it was the desire to see it flourish, covered with grass or wheat, that gave us strength.

As we moved towards Kletskaya we saw German defensive positions half-buried in the earth, as well as guns and tanks turned inside out by our artillery fire. More and more often we came across Romanian soldiers with white flags. They were a laughable sight. They went along singing our song: ‘Little Katya went out to the riverbank ...‘ It seems our famous katyusha rockets had made an impression. I have to say that the Romanians did not look much like proper soldiers. They were like one big gypsy caravan, and their uniforms were a strange mish-mash: battered sheepskin hats, all sorts of rags around their necks and on their feet. They weren’t enjoying the Russian frosts.

We crossed back over the Don, from the right bank to the left, near Golubinsky. Around that time I was called to HQ and ordered to drive the divisional commissar to the battery. We set off in a half-track. It was the middle of the night by now. A ferocious frost had formed a crust on the fallen snow. There was a monotonous white nothing every way you looked. We somehow went past our own guard post and didn’t even notice when we crossed the little Chervlenaya river. Completely unexpectedly we came upon a sentry who must have been half-asleep or half-frozen, because too late he shouted out in German ‘Halt!’

I instantly jumped out of the cabin and shoulder-barged him as I hit the ground. He went headfirst into a dugout. I tossed a few grenades behind him. This alerted the other Germans with him, and they began shooting wildly. A volley from a machinegun made a string of holes in our half-track and mortally wounded the commissar. I jumped back in and drove off, steering with one arm while trying to support the commissar with the other. I could feel him getting heavier and heavier. He was dead by the time we found our way back to the division.

THE SECOND ARM OF THE PINCER

The Germans did not yet suspect that the attack on the upper Don was merely the first stage of the Russian plan, that it represented only one half of a giant pincer movement. The Russians had done a fine job of keeping the Germans in the dark. They had hidden their build-up by moving men and materiel only at night, and by disguising the hardware. It is not easy to hide a fleet of tanks on the open steppe, but there were special units dedicated to the magician‘s art of camouflage - maskirovka, in Russian. Ivan Dovbishchuk was second-in-command of the First Guards Army‘s Chemical Section, and he used his scientific knowledge to keep German reconnaissance away. He was learning all the time.

An example of the importance of camouflage and basic cover was the stationing of a tank corps in the jump-off zone. To the south of Kotluban station there stretched deep ravines, and the units of the tank corps had parked their tanks right up against the sides of one of them and camouflaged them to blend in with the colour of the terrain, which was clay.

The decision had already been taken to use obscuring smoke. We selected a site for the smoke machines, which were fairly cumbersome things, and during the night we earthed them up well and camouflaged them with branches of wormwood. These machines stayed on the forward rim for several days while we were waiting for the right wind direction, and despite repeated enemy bombings and artillery raids there were no losses of men or equipment.

Using smoke machines on the forward rim proved inexpedient. So we deployed smoke charges to produce a smokescreen that concealed this wing of the army. It also became clear that it was not a good idea to use planes fitted with smoke devices to produce smokescreens, as the attack planes had to fly at such low altitudes that many of them were brought down by anti-aircraft fire. Later, planes were routinely used to drop smoke bombs and blind the enemy.

Similar measures disguised the stealthy preparations of the three armies that made up the southern pincer. The Russian 64th Army lay in wait south of Stalingrad in the bulbous salient dubbed the ‘Beketovka Bell ’. On its left flank, behind the archipelago of frozen water known as the Sarpa lakes, were the massed ranks of the 57th and 51st Armies. The Russian intention was to strike once again at the thinnest point in the Axis chain of defence. Here, as in the north, the unfortunate weaklings were deemed to be the Romanians: General Constantinescu‘s Fourth Army. The second attack was scheduled to take place on 20 November, a day after the northern offensive. The force was to dash to the north-west and link up with the armies heading south-east towards them. The two pincers were to meet and close the trap at Kalach, just east of the Don.

The southern arm had less distance to cover and fewer rivers to cross. This is why it was scheduled to set off 24 hours later. The timing of the attack was crucial, but on the morning of the 20th conditions did not look good. At six o‘clock, two hours before the opening artillery barrage was due to begin, a fog as thick as milk obscured the entire attack zone. The Russian aimers could not see the ends of their gun barrels, let alone the enemy‘s positions.

General Andrei Yeremenko - the stocky, pudding-faced commander of the Stalingrad front - was on hand. He set out for his forward command post at precisely seven o’clock in the morning. The fog was looking a little thinner as he made his way, but he could see it was still not nearly clear enough to shoot by. He had already had one phone call from the Kremlin that morning, asking him if he was quite sure that the offensive was going to begin on time. He had managed to fob off the functionary on the other end of the phone, but he knew that Stalin himself was wanting to hear some good news. And Stalin did not like his generals to keep him waiting.

By 07.30 I was at the forwardmost observation post of the 57th Army on Height 114.3, said Yeremenko. On a day with good visibility you had a remarkable view of a broad landscape from this point. You could certainly see the entire area of our attack. But the fog was still thick, and visibility was nowhere more than 200 metres. The artillery men were anxious. The Stavka called me to demand that I ‘get on with it’. I was forced to explain to the members of the general staff (not entirely tactfully) that I was not sitting on my backside in an office, but was on the battlefield, and so was in a better position to see when it was right to begin.

It got to nine o’clock. Everybody was nervously awaiting the signal. The infantry were hugging the ground, ready to go in. The gunners loaded their cannon and stood to, holding the cord. From somewhere behind us came the growl of tanks as their engines were warmed up.

Then the fog started to lift and scatter. Visibility was approaching normal. At 09.30 the order was given to start the barrage at ten. So in the end, the start of the counterattack on the Stalingrad front was held up by fog for two hours. The katyushas played their music first. Then the artillery and the mortars began their noisy work. It is hard to express in words what one feels listening to the many-voiced choir of an artillery cannonade before the start of an offensive. But what one feels above all is pride in the might of one’s homeland and faith in victory. Only the day before our slogan, which we spoke through gritted teeth, had been ‘Not one step back’. And now the Motherland urged us forward. The day that the people of Stalingrad had been waiting for had arrived.

A few minutes before the tanks and the infantry were due to go in, we laid down some mortar and machine-gun fire. And right before the attack we let off the powerful M-30 mortars. That was the signal. Out of their foxholes rose the endless lines of our soldiers. I could hear the long, continuous cries of‘hurrah!’ and the workmanlike clatter of the tanks.

Right at the beginning of the attack, a strange thing happened. We had decided that the use of the big mortars would be a signal for the start of the artillery attack, and that the second time they were used would signal the start of the infantry and tank attack. A simple system which, one might think, everyone would understand. But no. I was scanning the whole front with my binoculars during the artillery bombardment when - oh no! -I saw that the infantry on the left flank were already rushing towards the first enemy trenches while the red-tailed heavy katyushas were still firing on their lines. I came out in a cold sweat. Once an attack has started it is impossible to stop. It seems that the commander of the 143rd naval infantry brigade, Colonel Ivan Russkikh, had got mixed up and gone in straight after the first signal. Fortunately it was on the flank and not in the centre. I decided to call off the artillery bombardment in this sector and to do something to help the 143rd brigade, who seemed to be doing well. Twenty minutes into the attack they had already reached the second line of trenches and were starting to disappear beyond the horizon. Near to me was the commander of the 13th Mechanized Corps. I ordered him to send his first brigade into the breach. He tried tactfully to point out that according to my own plan the 13th Corps was due to go in on a different sector, and in two-and-a-half hours‘ time. ‘I know that, comrade Tanaschishin‘, but the situation demands changes. Send in the brigade.‘ I said.

Twenty minutes later, they too disappeared over the horizon without encountering any resistance. A second brigade followed. Even before the barrage finished, we had two brigades in the rear of the enemy, then the entire 13th Mechanized Corps went in after them. By manoeuvring quickly deep behind the enemy defences, they made a great contribution to the success of the attack. So sometimes in war you can make use of an unforeseen and chance event to keep things right, or even to strengthen your position - so long as you do not lose your head and don‘t stick too closely to the rulebook.

One soldier who needed no lordly lessons in improvisation from the commander of the front was Pulat Ganiyev, the sheherezade of the Soviet Fourth Cavalry Corps. Soon after the counter-offensive began he found himself in a tricky spot that Ali Baba himself would have recognized. He had been sent to catch a ‘tongue’ - a German who could be interrogated for information about enemy dispositions.

Ganiyev was a courageous scout, and a clever one too, wrote Pulat Ganiyev. His commanders valued him not only for his boldness and valour, but also for his ability to solve problems and understand events. It sometimes happened that several scouts would be sent out to catch a tongue, but would not come back - because they had been killed. No such thing ever happened to Pulat Ganiyev. Of course it was not easy, indeed there were many difficulties along the way, and Pulat risked his life hour after hour. But Pulat knew that he always had to do his duty as a soldier.

So it was that one day Pulat Ganiyev came to a village. He went to look for some hay for his horse. But this happened in the depths of the frosty winter, and here in the steppe by the River Don, there was no hay to be found. Ganiyev went to one farmyard, then to another, and nowhere was there so much as a single straw. Then Ganiyev went to the very last yard, on the edge of the village. He climbed into the mow, because he knew where peasants kept their hay in wintertime.

And lo and behold, there was plenty of hay. Pulat grabbed one armful, then another, so that he could tie them and take them to his horse. Then he heard something rustle, and it seemed to him that there was someone in the big pile of hay - perhaps none other than a German. So pointing his gun, Ganiyev shouted loud, telling them to come out. Imagine his surprise when out of the pile of hay came four armed Germans.

‘Throw down your guns,‘ commanded Ganiyev. And though the fascists did not know the Russian language, they knew well enough that this tall, strapping soldier was telling them to drop their weapons. What they didn’t know was that Pulat was all alone; they were sure that there were other Soviet soldiers in the yard. What was Pulat to do? Because as soon as these fritzes realized that he was on his own, they would surely attack him. But they did drop their guns. Ganiyev ordered them to approach one at a time, and he kept his gun pointed at them all the while. As he was doing this, a Russian soldier happened by, and with his help the fascists were delivered to the proper place.

One of the Germans, by the way, had indeed hidden a pistol, and could have shot Pulat Ganiyev had Pulat not been so watchful. Bold Pulat was recommended for a medal for his actions that day.

THE TRAP BEGINS TO CLOSE

The Germans had known that some kind of an offensive was coming, but they were completely taken aback by the scale of it. Hitler had managed to convince his General Staff that the Russians had bled themselves white inside Stalingrad, and that any counter-attack would be a feeble gesture at most. This wishful thinking had filtered down to all levels of the Sixth Army, but certain precautions were taken nevertheless. As the Russians attacked, some valuable German units were withdrawn to the west, beyond the reach of the approaching enemy, and they were replaced with regular infantry. Wilhelm Beyer was unfortunate to belong to one of the units that were heading east, towards Stalingrad.

We marched in across the Don. There was an emergency bridge, built by the pioneers, narrow, only two lanes wide. SS troops were on the second lane, pulling out from the unformed pocket. Some were thinking to themselves that these were elite troops that needed to be ‘spared’. We marched eastwards in close formation, namely into the all-round hedgehog defence position that was forming. Long columns three abreast. I’d been detailed a position right up in front. We became increasingly aware that these special units going in the opposite direction were hurrying out with their baggage convoys and guns. We poor buggers, the privates, were going to take their place. Our none too cheerful mood sank even further.

Some troops had a rather more dramatic awakening. Corporal Heinrich Simonmeier was sent to a supply dump at a German airfield on the Don steppe to get a new uniform. ‘But instead of the expected Junkers he said, ‘Russian tanks came and closed the pocket.‘ Gunter Toepke, quartermaster for the Sixth Army, was near Pitomnik airfield on 21 November, far from the prongs of the Russian attack. But in the course ofa couple ofdays’ hectic travel, he felt a growing sense of claustrophobia. The Russians were closing in: it was like watching the steel doors slam shut on a bank vault - knowing that you are on the inside.

I was on my way to Chir from my main supply dump at Karpovskaya. I was going to supervise the loading of our horses. On the way through Kalach I heard all sorts of rumours from the supply troops stationed there: talk of a Russian offensive from the Kremenskaya bridgehead. It was said that the Russians had already broken deep into our lines. Things were supposed to be looking particularly nasty for the Romanians, our neighbours to the left. In the distance I could hear the rumble of a battle. There was nothing more to be learned for now.

I had no difficulty getting over the Don High Road from Kalach to Chir. I spent the night there. But the next day I couldn’t cross the High Road: it had already been taken by Russian tanks. To get back I had to drive back to the southern bridge over the Don, at Chirskaya. I was not in the best of moods as I bounced along in my car, heading east over a dull tract of steppeland. Suddenly some of our soldiers jumped out of a bush and frantically waved me down. They asked me where I had come from. And then they told me: ‘Four Russian tanks came up that road a quarter of an hour ago. We fired at them with our anti-tank gun, then they turned around and headed into the steppe.‘

You‘ve been seeing ghosts. How could there be Russian tanks here. There might be some up in the north, on the other bank of the Don, but surely not here in the south?‘

The anti-tank team knew nothing of the Russian offensive in the north. ‘They must have come from over there.‘ they said, pointing away to the south. ‘We‘ve been hearing sounds of battle from there all day.‘

"From over there. That‘s the way to Tinguta.‘

‘Yes, the noise is coming from Tinguta.‘

Suddenly it dawned on me. Damn it all, it looked like the Russians were attempting a large-scale pincer movement to box the Sixth Army into Stalingrad. Kalach was the meeting point.

Ever more worried by the growing sound of battle from the south, I drove on to Karpovskaya. I knew that there were no troops there in the south apart from the Romanians. So the Russians had gone for the Romanians both in the north and the south, and had apparently broken through.

That same night I telephoned my divisional commander and told him of my concerns. The divisions inside Stalingrad had no idea of what was going on, of what was being played out deep in their rear. Around that time I put my supply units on alert: bakers, butchers, mechanics, horse grooms and drivers were formed up into battle units and made to man a line around our headquarters. There was no more I could do for now.

While Toepke‘s bakers and candlestick-makers waited, combat units were fighting to keep a corridor open to the west, to prevent the Sixth Army from becoming completely surrounded. Lieutenant Hans-Erdmann Schonbeck, 22 years old, was a tank commander. Two days earlier he had been idly thinking that at this time of year he usually went pheasant-hunting with his father, back home in Silesia. Now, out in the eerie steppe, the Russians were the hunters, and he was the prey.

Drifts of dense fog that seldom parted turned the steppe into a wonderland. But it was an evil kind of magic. You could no longer tell friend from foe, or often not until it was too late. And now it suddenly turned cold. In the space of a few days, bitterly cold. I’d already lived through the previous winter outside Moscow, but here there was no cover, no forest, no trees, no shrubs, just this constant biting wind.

And with the cold came the great catastrophe. The Russians advanced from the north and the south. On the 19th November, the first day of this offensive, we already seemed to be largely encircled. Once again the Panzer men had to chase around like firemen. We were immediately turned round 180 degrees and then moved westward for a counterattack. But the forces that were massed against us were enormous!

During my years in Russia I had developed very keen antennae for the strength or weakness of my own situation. I was just a Frontschwein, so I was hardly ever aware of the overall picture. For me it was always just a matter of carrying out the current order. And the orders were coming thick and fast at this time. At this point we were already worn down and exhausted from attacking the city. The number of our operational Panzers had shrunk by a half, we had little fuel and only enough ammunition for a few days‘ fighting. We fought moving westwards with our remaining Panzers - but firing back eastwards as we went!

As the Germans and Romanians reeled back, the Russians seemed to gain confidence. For Grigory Onishchenko, a staff officer with the 51st Army, the early successes were a natural consequence of the careful planning that had gone into the operation.

About two weeks before the offensive we already knew what units we were going to be given, which elements of the air force were going to support our attack. As the operation got closer we could see how the strength and the power of our armed forces was growing - we could feel it. All of us who knew about the operation or took part in devising it were impatiently looking forward to H-Hour. On the day, the breakthrough was so swift that by 11 o’clock the General Staff of the Army broke camp and continued its work while moving forward. As we followed in the traces of the forward units we saw many curious sights. For example, as we drove towards one village, we saw a huge column consisting of many regiments, complete with horse-drawn artillery, field kitchens, vehicles, food trucks. It was moving towards the rear, and it seemed strange for a moment that such a large force of our men was heading backwards. When we got closer we saw that regiment after regiment was being escorted by a few machine-gunners, one of whom had a note asking for someone somewhere to disarm these Romanians and take them prisoner. It was the Romanian 9th Army, utterly demoralized.

There were other eye-opening sights to be seen during the advance of the southern pincer. Konstantin Artashkevich was with the 13th Tank Corps, the unit that General Yeremenko had wilfully tossed into the gap in the line during the first hour of the attack. From his gun turret he saw a clever piece of improvisation that testified to the Russians’ growing skill.

After a tank battle on our sector three German aircraft came flying in and began to bomb our forwardmost line. The planes came in very low, no more than 300 metres above the ground, and at that moment one of our soldiers lay down on his back and shot upwards at the planes. One of them crashed into the ground not far away. The others, seeing that one of their number had been killed, turned tail and flew away. That soldier was given a medal for bringing down a plane with just his rifle.

THE FLIGHT OF THE NIGHT WITCHES

The Luftwaffe had enough problems without that kind of bad luck. Their superiority in the air was diminishing rapidly, and Russian air power was growing at the same rate. Germans who had looked to the skies for reassurance in the summer and autumn months now feared the worst every time they heard the sound of an approaching plane. Stories circulated about Nachthexen - ‘night witches’ - fanatical Russian women pilots who bombed bridges and forward airfields at night. It was said that German pilots automatically received the Iron Cross for shooting one down. The tale of the night witches played to all the German fears about the unnaturally aggressive nature of Russian womanhood. Many of them had seen the female corpses in the ack-ack emplacements and pillboxes on the approaches to Stalingrad in August. Perhaps that was where the rumours originated. Or perhaps not - because the stories were true.

The night witches were the women of the 46th Guards Night Bomber Regiment. All the pilots in this unit were female, and so were the ground crew. The pilots flew tiny two-seater aircraft called the Polikarpov U-2. This obsolete biplane was slow, but it was very quiet. The Germans called it the Ndhmaschine, the ‘sewing machine’, because of the homely clickety-clack of its engine, while the Russians affectionately christened it the maize-cutter - kukuruznik - for its dinky little propeller.

Notwithstanding its old-fashioned profile and its cosy domestic nicknames, the U-2 was an effective aerial weapon - one of the surprise successes of the war. Beneath its small undercarriage it could carry a payload of 520 pounds (240kg) of bombs. It was used almost exclusively at night because the darkness made it less vulnerable to attack by faster aircraft, and in the general cacophony of battle it was hard to hear it coming. So the U-2 was almost undetectable, and the falling bombs of the night witches materialized as if from nowhere, like a curse.

Zhenya Zhigulenko was a pilot with the 46th Night Bombers. She flew almost a thousand missions, and was awarded her country’s highest military honour - Hero of the Soviet Union - at the age of 24.

Flying was very frightening, said Zhigulenko. We would take off ten or more times a night. During some flights we’d have to tear free with our hands the bombs that had got stuck under the ice-covered wings. The problem was that sometimes we used bombs that had been captured from the Germans and their lugs didn’t properly fit our bomb-carriers. When all is said and done, one can reconcile oneself to many things: to being blinded by searchlights and shot at by anti-aircraft guns, to seeing bullet-holes in the wings of one’s plane, to being unable to speak and to feeling one’s knees quaking after a touchdown, and even to missing a friend after a mission and hoping against hope that she will return.

The 46th were not the only female pilots on the Stalingrad front. There were also two all-woman squadrons in the 586th Fighter Regiment. Colonel AI Gridnev was their (male) commander.

The girls acquitted themselves with great honour on the severe testing-ground of the Stalingrad front, said Gridnev. As flyers they were no less skilful than the men, they were also just as fearless and full of valour. They made a worthy contribution to the destruction of the fascist forces at Stalingrad. The girls fulfilled all kinds of combat missions. They attacked enemy bombing formations, covered ground troops from air attack, and carried out raids on the enemy’s ground forces.

I cannot help but feel emotional when I recall the selfsacrifice of Raya Belyayeva, Katya Budanova, Anya Demchenko, Klava Nechayeva, Inna Lebedeva and others. These girls knew no fear. There was one time when Raya Belyayeva and Anya Demchenko were patrolling above a railway junction near Stalingrad. They spotted forty enemy bombers heading towards them. Two girls against forty of those damn vultures! There was no time to think or to wait for help. They used their advantage of height and speed and went into the attack. They sent two Junkers down in flames, and at the same time disturbed the attack formation of the enemy, who consequently dropped their bombs early and missed their target.

Then there was Katya Budanova, one of the most courageous of my fighter pilots. On one occasion she was returning from a mission, and her fuel and ammo were already low. Katya came upon twelve German bombers heading for our front line. Like Belyayeva and Demchenko, she had no hesitation about going into the attack. But she only had sufficient ammunition for one pass. She fired off the last of her cannon at the lead plane, which broke up in the air. She could now have broken off the attack. But she thought: they don’t know I have no guns left. She dived into the formation of bombers again and again - imitating an attack but without shooting. The heavy bombers knew that they could not manoeuvre out of the way of an attack by a Soviet fighter. They would have been worried about colliding with each other in the air. So they jettisoned their bombs onto the heads of their own men.

There were times when the pilots carried out seven missions in a day. Sometimes my girl-pilots went without sleep for two or three days at a time. And there were days when the joy of our victories was tempered by grief. Klavdiya Nechayeva and Inna Lebedeva, gallant flyers both of them, died over Stalingrad.

The women of the 586th Fighter Regiment flew Yak-Is, an aircraft with the same dash and elegance as the Hawker Hurricane. But there were also actual British Hurricanes on the Stalingrad front, part of the mass of hardware given to the Soviet Union under the lend-lease arrangement with the USA and Britain. Some Russian pilots had an opinion of the Hurricane that would have surprised their British counterparts, but which bears out the offhand and disparaging remarks made by Stalin about the plane on the day he met with Zhukov and Vasilievsky.

We were told that we had to get to know the English Hawker Hurricane in a hurry, said I Stepanenko, a Russian flyer. These aircraft, or rather the bits that made them up, lay in huge wooden crates. We had to unpack them and put them together ourselves - and that was part of our education. We already knew that these planes were of an obsolescent design, and we knew their weaknesses.

But what we subsequently discovered went beyond the low expectations we had of them. The planes had a water-cooled Rolls-Royce engine with a honeycomb-style radiator. In our winter, the radiator often froze up and the engine broke down. Moreover, the planes had very inadequate firepower - and a wooden propeller which broke too easily. The centre of gravity of the plane was too far forward, so on soft ground or on snow the tail would seesaw upwards and the nose would go into the ground. When that happened the propeller would break off. We were given very few spare props, because the English had not thought about the ‘behaviour‘ of their product.

The lack of spares was overcome when Hurricane propellers began to be produced locally. As for the perceived tendency of the Hurricane to tip on to its nose, a very Russian solution was found to that problem. Stepanenko tells the story.

I have a very simple idea,‘ said engineer-lieutenant Aleksei Melnikov. ‘When you taxi out onto the runway for take-off, I’ll sit on the tail of the plane. My weight will be enough to move the centre of gravity to the back. That will stop the plane nodding forwards.‘

We tried it out. Melnikov rode around the airfield a couple of times. The aeroplane speeded up and slowed down, got to the point of take-off and set back down. And the prop did not plough into the ground. ‘Well then, lads, you‘ll have to learn to saddle the Hurricane,‘ joked the senior engineer, Captain Aivazov. ‘Those of you who have never mounted an Orel trotter can ride on the back of an English filly instead.‘

It was a risky business. There was one time when the pilot forgot that he had a member of the ground crew sitting on the back and he accelerated and took off. He soon realized what he had done and landed. No harm came to the ‘horseman’, except that his hands were frozen and he had turned blue.

THE BRIDGE AT KALACH

The southern arm of the pincer made good progress on the first day and a half. By 21 November, it had got as far as the village of Buzinovka, halfway to Kalach. The forces of the northern arm, meanwhile, had covered 60 miles (96km) and were on the Liska River, 25 miles (40km) from the west bank of the Don. It was imperative to gain control of the bridge near Kalach. If the Germans could retreat across it and blow it up, then the trap could not be properly closed. And if the Germans could hold the bridge, then their supply line would still be viable. It had to be taken, and taken intact.

The capture of the Kalach bridge is one of the legends of the battle of Stalingrad. Like all legends it has been altered in the telling and now exists in many different versions - some of which are closer to the truth than others. Here is the story of that coup de main as recounted by the man who pulled it off: Colonel Grigory Filippov, commander of the 19th Tank Brigade. His account begins on the night of the 21st. He had been ordered to push ahead of the main advance with a column of tanks and armoured cars. Along the way he had already blundered into some German armour and taken a battering. Now it was first light, and he was heading towards the river. It was a race against the clock, a mad dash full of frustration and firefights.

We were left with five tanks, an armoured car with a communications officer, and five trucks of a motorized brigade carrying fifty or so soldiers. We continued along the road to the crossing and a kilometre further along, about two or three hundred metres to the right of the road I saw a platoon of Germans getting up from the ground on the edge of a copse. They had been asleep and now they were washing themselves with snow. Of course, with the advantage of surprise we could easily have killed them all. But that would have meant losing time. And the noise would surely alert the Germans at the crossing. I decided to move on without engaging, and gave the necessary order to the commander of the tank company, who was riding with his turret open in the tank ahead of me. But further along we did have to take out two or three enemy trucks which were coming down the road towards us. We were risking giving ourselves away, but if we hadn‘t done it they would have alerted the combat units behind us.

Continuing down the road, we caught up with a cart being pulled by an old Russian man by the name of Gusev. Sitting on the cart was a German. We killed him because, according to Gusev, he liked to torment prisoners. We asked Gusev where the crossing was, and he told us that the Germans had blown up the old bridge, but built a new wooden one a little further upstream. To get there you had to take a different road.

From Gusev’s directions it became clear that the right road led off a crossroads that we had already passed. What were we to do? Returning to the crossroads would mean going back past the Germans we had seen earlier, only now they would be battle-ready. It also meant wasting more precious time fighting them, and losing the element of surprise. Then Gusev remembered that there was another road somewhere nearby that led to the crossing.

We spent a long time looking for it, and had to go quite a way back. I was already starting to wonder whether this Gusev was perhaps a traitor. I sat him on a tank next to Nikulin. Things were getting difficult. I was thinking that it was now going to be hard to take the bridge by surprise. There was nothing but bare steppe all around. I couldn’t help thinking about my brother and his three children, all of whom had died in the siege of Leningrad. I hated the fascists so much that I was determined to make them pay somehow. I began to look for some place to stop and take up a defensive position. To the right was a deep ravine - it was better than nothing. Then Gusev said that he had found the road.

Now we turned off onto the new road. The right bank of the Don was high at this point, but the road led gently downwards. Along the way we took out an SS-man, a sentry. I thought, there goes the surprise once again -there must surely be a guard post around here somewhere. We descended towards the Don, and saw that the road did indeed lead along the bank. We turned left along the river, but could see no crossing. Then I was told that the trucks had run out of fuel.

Damn our luck! I looked around and there I saw a middle-aged man, Russian, in civilian clothes. I asked him if he knew where there might be some fuel around here. He said that there was a German fuel dump nearby, that it was dug into the steep side of the riverbank just at the point where we turned left along the Don. The trucks could only get at the fuel dump one at a time, and then they had to reverse out before the next one could go in. I only let my men take a bucketful each. We dare not dawdle, as we had lost enough time as it was.

Finally we were once more on the road leading upstream. But there was no bridge to be seen. But then beyond a little bend in the road, to the right of us, there it was. A little further on and we were close enough to see the guards on the bridge. We got quite close before we stopped, and then a machine-gun opened up on us from a long way behind. That meant that the Germans had spotted us. Possibly we had passed by a guard post when we killed the sentry, and someone had telephoned ahead.

There was not a moment to lose. I ordered the infantrymen from one of the trucks to head out across the ice of the river (it was quite thick near the bank) and take up positions on an island in the middle of the flow. This island hid part of the crossing from view. I lay down on the left side of the lead tank and got ready to shoot. The other trucks and tanks followed me. We drove up level with the island. There was no shooting from the other bank of the river. As we passed the island we could see that most of the defenders on the bridge were standing in clumps at the far end, on the left bank of the Don. On this bank there was just one pillbox and a sentry.

The thought popped into my head: they are not ready for a battle, they haven’t reacted to the gunfire coming from behind us. We drove onto the bridge. The Germans did not sound the alarm until we got to the left bank. There was a short skirmish, and the guards were dead.

That is how the only crossing in this area was taken, the only escape route for the Germans. The capture of the bridge was an important event. If we had not succeeded in taking it, then we would have had to force the Don, and much time and many men would have been lost.

The tanks adopted a circular defence on the bridge at the left bank. The tanks added steel to the defence, and allowed the motorized infantry to manoeuvre in any direction from which a threat might come. The Germans were terrified of our tanks. The explosive charges on the bridge were disabled. We used an axe to cut through the thick cable which ran all along it.

With the capture of the bridge the trap was shut. The Germans at Stalingrad were surrounded. Filippov’s men proceeded into the town of Kalach, where they liberated a POW camp. Most of the inmates were on the point of starvation. One of them was Anna Andreyevskaya, the nurse who had so manfully stood up to the Germans on the day of her capture in September. She had not expected to get out alive.

There were about 2,000 people in the camp, said Andreyevskaya. Every day, thirty or so dead bodies were carted away and buried somewhere. On November 23rd, before the Soviet forces arrived, the Germans took ten of us - nine men and me - and put us before a firing squad. They shot me, but by some fluke I was only wounded in the shoulder. So I consider November 23rd to be the day when I was born for a second time.

For all the attacking forces, 23 November was a memorable day. On that day, the two pincers linked up at the village of Sovetsky, not far from Kalach. Operation Uran had succeeded, and the Russians were jubilant. They had scooped up thousands of Germans and Romanians like fish in a giant net. The Soviet High Command immediately invited the press to come and admire their catch. Western journalists were offered a visit to General Chistyakov of the 21st Army at his new frontline HQ. Henry Shapiro, the Moscow correspondent of the United Press, was one of the party. He started his exploration of the battlefield at Serafimovich, the jump-off point for Chistyakov‘s army.

Well behind the fighting-line there were now thousands of Romanians wandering about the steppes, cursing the Germans and desperately looking for Russian feeding-points, and anxious to be formally taken over as war prisoners. Some individual stragglers would throw themselves on the mercy of the local peasants, who treated them charitably, if only because they were not Germans. The Russians thought they were ‘just poor peasants like ourselves‘.

Except for small groups of Iron Guard men who, here and there, put up a stiff fight, the Romanian soldiers were sick and tired of the war; the prisoners I saw all said roughly the same thing - that this was Hitler‘s war, and that the Romanians had nothing to do on the Don.

The closer I moved to Stalingrad, the more numerous were the German prisoners. The steppe was a fantastic sight; it was full of dead horses, while some horses were only halfdead, standing on three frozen legs, and shaking the remaining broken one. It was pathetic. Ten thousand horses had been killed during the Russian breakthrough. The whole steppe was strewn with these dead horses and wrecked gun-carriages and tanks and guns - Germans, French, Czech, even British (no doubt captured at Dunkirk), and no end of corpses, Romanian and German. The Russian bodies were the first to be buried. Civilians were coming back to the villages, most of them wrecked. Kalach was a shambles: only one house was standing.

General Chistyakov, whose HQ I finally located in a village south of Kalach, said that, only a few days before, the Germans could still fairly easily have broken out of Stalingrad, but Hitler had forbidden it. Now they had missed their chance. He was certain that Stalingrad would be taken by the end of December.

German transport planes, Chistyakov said, were being shot down by the dozen, and the Germans inside the Stalingrad pocket were already short of food. The German prisoners I saw were mostly young fellows, and very miserable. I did not see any officers. In thirty degrees of frost they wore ordinary coats, and had blankets tied round their necks. They had hardly any winter clothing at all. The Russians, on the other hand, were very well-equipped—with valenki, sheepskin coats, warm gloves, et cetera. Morally, the Germans seemed completely stunned, unable to understand what the devil had happened.