8

OPERATION RING

There was never the slightest chance that Paulus would agree to the Russian surrender terms. He believed in Hitler, and perhaps he still had faith that the Führer might find some way to turn the situation around. From a military point of view, he could tell himself that by tying up Russian forces here on the Volga he was aiding the withdrawal of the rest of the German armies in the south. And in the end, he had an absolute personal commitment to the idea that a soldier should do as he is told. ‘Ich stehe hier auf Befehl’ he wrote laconically to his wife in his last letter from the Kessel: ‘I’m here because I’m ordered to be.’ Paulus needed no other justification for his actions.

Operation Ring began the day after the second parley attempt. It was a freezing, bitter Sunday. The Germans seemed to be holding their breath, steeling themselves as they waited for the blow to fall.

The morning of the tenth of January was a cold one, wrote one Russian officer. The wind was whipping up into a blizzard. Everything was ready. In the fascists‘ camp there was a deathly, oppressive silence. No wailing from the German six-barrel mortars, no crackling of machineguns. It was as if the enemy was hiding, waiting for death to come. They knew from our leaflets, and from the warnings that had been blasting out from the propaganda trucks for the past three days, that they were about to be dealt a killer blow.

At 08.00 came the preliminary commands ‘In position!‘ and ‘Set watches!‘, followed after a brief pause by signals over the radio and telephone giving the command ‘Ready fuses!‘ and, finally, at 08.05, the command ‘Fire!’ For 55 minutes, a tornado of fire raged over the German trenches. The enemy was pounded by seven thousand guns and mortars.

At 09.00 the infantry went in to the sound of the ‘Internationale‘ with their regimental standards unfurled.

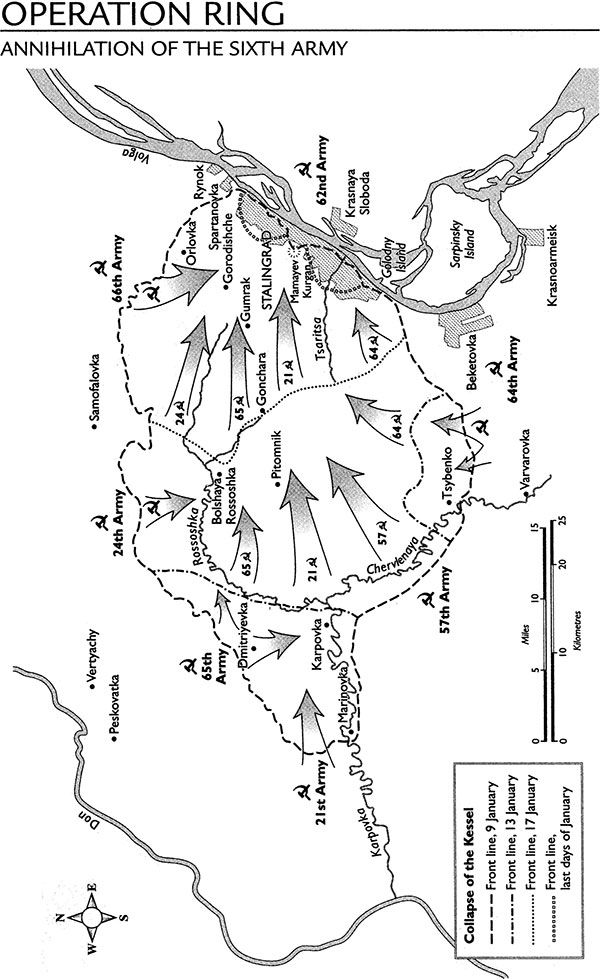

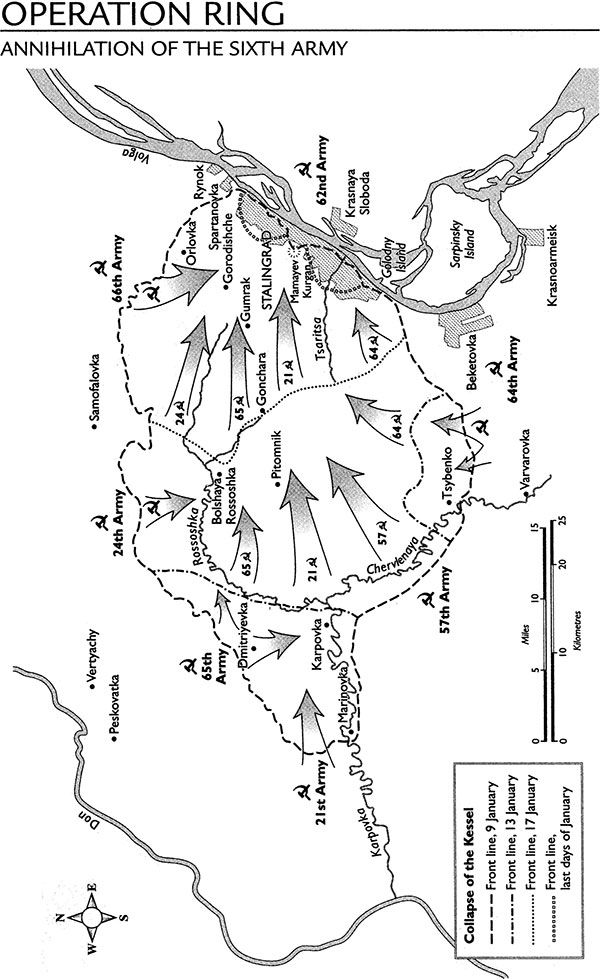

The Kessel was attacked from all directions at once: the 57th and 64th Russian Armies went to it from the south, the 65th, 24th and 66th Armies from the north. Chuikov’s 62nd Army maintained its terrier-like grip on the Germans at the eastern side of the Kessel, in the howling ruins of Stalingrad itself. From the west came the hardest blow of all, from General Chistyakov’s 21st Army out on the open steppe. This part of the offensive was directed against the protuberance of the Kessel known as the ‘Marinovka Nose’.

The aim was to smash through the defences on the outer rim and drive towards Pitomnik, the airfield in the dead centre of the Kessel. To capture Pitomnik would be to stab at the heart of the German Sixth Army, because it would make it well nigh impossible for the airlift to continue. Here too was the main hospital, along with the nerve centre of communication for the Germans and, under tarpaulins and armed guard, the last supplies of food and ammunition. If Chistyakov’s men could take Pitomnik then push on into the city, they would cleave the Kessel in two like a clean knife slicing through a rotting apple.

The German forces were in a catastrophic position, said Matvei Kidryanov, an intelligence officer with the 21st Army. Transport planes were dropping provisions, munitions and fuel. But recently they had been dropping them ever more frequently right into our laps, as we knew all the ground signals that told the planes where to drop their cargo, and we were making good use of this knowledge.

A group of German transport planes appeared above the observation post, protected by fighter planes. They circled above the steppe like kites, searching for their troops. True, only yesterday there were still Germans here. Our orange rockets flew up. This was the Germans‘ ‘Drop the cargo!‘ signal. The planes started dropping their cargo onto our observation post. This time, as it turned out, they were dropping not food and munitions but whole packages of sheepskin coats and warm uniforms for the fascist troops. From every direction, our troops were running out to the packages and dismantling them.

No sooner had the planes dropped their cargo than our anti-aircraft gunners started shooting at them. Several enemy planes were shot down. The soldiers would run up to downed and burning German planes to see if there was anything inside them that they could use for life on the front line. From the parachutes, they would usually sew themselves camouflage jackets, tobacco pouches, even underwear. And from the celluloid glass they would make all kinds of knick-knacks: beautiful dagger and knife handles, cigarette cases, pipes, cigarette-holders, and many other things. One of our scouts, Zhezhera, ran up to a burning plane that had fallen not far from us. A little later he returned with his booty. Bathed in sweat, he was dragging the remains of a burnt parachute, the pistols of the dead crew, and some fragments of plastic.

Three days after the start of Operation Ring, Kidryanov‘s forward unit was closing in on its first objective - when suddenly it happened upon a mysterious sight.

We were approaching Pitomnik. Up ahead of us, in the middle of the deserted steppe, there appeared against the night darkness the outline of some large town that was not on the map. ‘It’s a city in the steppe‘, someone said, ‘It‘s like Serafimovich!‘ When we drew closer, we saw a mass of vehicles: it was a city of cars.

The Germans had abandoned around 5,000 vehicles here. They were parked in orderly rows according to their make, and from a distance they looked like a town with many streets. There were covered trucks, repair trucks, armoured personnel-carriers, tanks, light vehicles, Opels of every type. The witty lance-corporal Zhezhera said to me: ‘Comrade Lieutenant-Colonel! There’s every make of car here: Opel ‘Captains’, Opel ‘Admirals’. The only one missing is the Opel ‘Corporal’, so I guess Corporal Zhezhera will have to fight on foot!’

The following morning there began a kind of pilgrimage to the city of cars. Our men started stripping the cars for spares, or taking the tyres. The drivers went about this task with particular zeal. The city of vehicles gradually started thinning out. A lot of dodgy characters showed up from various different units. They picked vehicles and drove them away. Army booty details turned up to make an inventory of the vehicles, but they arrived too late. All the good vehicles had already been taken by combat units.

Outside Stalingrad nearly all the officers, right down to the platoon commander, and in some cases even sergeants with their scouts and signallers, were driving around in captured vehicles. Only once the fascist forces had been routed were all the non-regulation vehicles handed over to the army booty depots.

There were still plenty of Russian fighters doing their job without the benefit of personal transport. For the mass of infantry, Operation Ring was a seemingly endless succession of route marches punctuated by vicious skirmishes. The walking was almost a greater hardship than the fighting.

Our battalion was ready to advance as soon as we received the order to break through, said a sergeant Kudryavtsev. There was no transport of any kind, the conditions were difficult, we made only short halts, and our provisions had run out. Night came, it was snowing and raining, and everyone, officers and soldiers alike, was encrusted in a freezing rind of ice. The command to halt was given, but no one could get to sleep beneath the rain and sleet. The night passed in the gloomy wood. Early in the morning the battalion moved out. Day was already breaking, and we wanted to eat, but there was no food, nor any command to halt. We were exhausted, and those who were starting to slow down held on to the carts so as not to be left behind.

Every weary soldier was feeling the sting of the frost. Nothing could be discerned of the Stalingrad steppe - just snow and more snow, blending into one with the horizon. However tired we were on the march, we had to keep going and hold out against the frost and the fierce winter. After a long march, we slept a deep sleep on the steppe of Stalingrad, in the open air, on snow and frost, and the next morning we got up, and there was ice underneath every one of us. But no one so much as coughed, no one had frozen to death or even got frostbitten. What willpower the Russian soldier has, what endurance and steadfastness! This is the secret of his victories.

The secret was not so much steadfastness as good supply and iron discipline. The Russian forces were all dressed in warm winter uniform consisting of quilted jacket and trousers, fur hat and felt boots. They all knew how to wind footcloths so as to protect the toes from cold (woollen socks were seen as an oddity by the Russians). Consequently, frostbite was practically unknown among Russian soldiers, and when it did occur it was treated as a punishable offence because it was so obviously preventable. In the German ranks, by contrast, frostbite was almost universal.

By 14 January Russian tanks and mobile artillery were within striking distance of Pitomnik, which was already under almost constant bombardment from the air. The Germans were reeling back towards the city in utter disarray, just as the Russians had done the previous August. Sergeant-Major Wallrawe was in one of the infantry units that felt the Russian fist to the Marinovka Nose. He was a tankman with the 16th Panzer Division, but had been transferred to infantry duties. For three days he had been pulling back, trying to do his part to keep the retreat orderly. His unit had withdrawn to the village of Karpovka. Wallrawe was defending the railway station when a Russian rifleman gifted him a ticket home.

I was wounded with a Russian bullet right through the stomach. With utter disregard for their own safety, Corporals Klaus and Ranz dragged me two kilometres on a strip of canvas. I was loaded on to a lorry along with several other wounded and taken towards the airfield. When we were still three kilometres away from our destination we ran out of petrol. Orders were given for the vehicle to be blown up. The wounded were left to their fate.

I crawled the rest of the way. Meanwhile night had fallen. I received first-aid inside a large tent. Several tents for wounded were hit or swept away in a hail of bombs from Russian aircraft. At 03.00 in the morning I was flown out of the Kessel in a Junkers. On that day the enemy was only 12 kilometres away.

Wallrawe was told that he survived the perforation of his stomach only because he had eaten nothing for the past six days. His life was saved by hunger. That is something he must have thought of often as he recuperated in a safe hospital bed.

Hordes of other Germans, wounded or merely crippled with famine, were meanwhile gathering at the airfield, desperate to win the right to be evacuated before the Russians arrived. Many thousands more were on the open road, where the temperature was around 35 degrees below zero.

Alexander Dohna-Schlobbiten, an East Prussian officer of impeccably aristocratic descent, was ordered to accompany General Hube on a visit to the front line. Though Dohna was old enough to have fought in World War I, he had never seen anything to compare with the horror now unfolding before his eyes.

It was the most profoundly shocking thing I have seen in my life. On the short drive to the front line there was an endless train of retreating soldiers, all of them streaming towards us. They had no weapons, often no shoes. Their feet wrapped in rags, their emaciated faces encrusted with ice, suffering from their wounds, they dragged themselves deeper into the Kessel. At the edge of the road lay the dead and dying. I saw people crawling on their knees because their feet were entirely consumed by frostbite.

Among this crowd was Raimund Beyer, who in November had been one of the last to enter the Kessel, and was now about to become one of the few to get out. He had been shot in both legs, but made it to the airfield. Yet before he could receive an official pass to be flown out he had first to be examined by a doctor, to check his injuries were genuine and that they conclusively put him out of the fray. ‘In my case the examination was over very quickly’ he said. ‘Age, high blood pressure and two heavily bleeding leg wounds seemed to have tipped the balance. I still remember his exact words as the doctor said to me softly, perhaps enviously: “Send my greetings to the homeland.”’

Now Beyer and the hundreds of other stretcher cases waited for a plane to emerge like an angel of salvation from the freezing fog.

I was driven to the airfield, that is, to one of the miserable barracks that were dotted about. There were military police all around, but not at all unpleasant, actually giving us a feeling of security, mingled with the feeling that this might be the first step towards being flown out. They followed every movement of those lying stretched out. But not for medical reasons, but to make sure that no unauthorized soldiers smuggled themselves in.

We lay in the barracks and waited. Night fell. We were arranged in rows in three groups, but in such a way that you could talk to those in the group lying directly behind you. All sorts of rumours were flying. At first I just listened, but then I stopped even doing that. All that concerned me was that I was lying in the first row, so that I could count on being on the first flight out. Then I dozed off again.

Soon people stopped talking to each other. Some were crouching, if they only had wounds in their arms or the like. The night dragged to an end. No plane arrived, three were scheduled. It got steadily colder. Weak tea and a crumb of bread did nothing to warm us up. At last the first plane arrived, landed, was unloaded and medical orderlies with three or four stretchers began loading the first row of those waiting as well as the few able to walk. Then suddenly out of the line waiting for the third plane, my old mate Leo Goschka, a real rough and ready Berliner, came hobbling over to me and called out: ‘Raimund, Raimund, stay where you are, we’ve always been together’ and turning to the military police who’d rushed forward: ‘Let me come along, I want to go with this lot’ But they instantly began to fend him off with the butts of their guns, thinking this was someone who was trying to fiddle his way in or jump the queue.

I called out to one of the military policeman. ‘Look, I’ll stay, and let someone else waiting for the third plane go. Til change places with him and stay with my pal.’ The man nodded and waved to two bearers who immediately carried me back. To avoid trouble, and so as not hold things up, he simply allowed the man lying next to Goschka to be brought forward. It was all done at top speed and the good old Ju took off with about 15 men.

It leaves a bitter taste to see others being flown out of the Kessel while you’re left to wait, unsure whether another plane will arrive. All eyes were fixed on the flight approach, that is in the direction from which the first rescuing ‘King’s horseman’ had come. Then - it was already getting light -two came almost at the same time. Some of the men quietly called out ‘There they are’. Others deliberately kept quiet, shivering with anxiety as to whether it would be their turn now. Things went even faster this time, and soon I was lying in the third plane, beside Leo Goschka. He lay down next to me.

I said something to Leo. Then the pilot half-turned his head and called out ‘That’s someone from Nuremberg, I can tell by your accent.’ I told him I was born right on the market square, opposite the Schoner Brunnen. He answered: ‘And I was born on the Förther.’ And immediately after that he said: ‘Here, this is for you.’

It was a loaf of bread, like the ones we were given by the slice in the Kessel. A corporal cowering in the corner now barged over to me, snatched the loaf of bread from me, hugged it to his chest, and forced his way back to his corner. He began to tear the bread apart like a madman, ripping hunks off and chewing. At the same time he was warding off several other hands that stretched out towards the loaf, long thin arms leaning over begging for some. He gobbled and gobbled. I was so taken by surprise that I couldn’t say a word and just indicated my displeasure with several dismissive waves of the hand. But nobody noticed. Everyone was so shocked that silence fell. After a short while the fury of those who’d lost out blew over, as the glutton who had wolfed down the bread now started getting stomach cramps and was rolling about and screaming and writhing. He was carried out dead from the plane when it landed.

Russian tanks overran Pitomnik airfield on 15 January, just as the selfish corporal was eating the last meal of his life. Many hundreds of Germans, including the helpless wounded, were killed in the attack on the airfield. Anybody who could walk or crawl now tried to escape to the east, towards the smaller airfield at Gumrak, which was just outside the city.

One soldier highlighted the surreal absurdity of this new retreat, which took him and his comrades deeper into the enemy‘s country: He said : This flight wasn‘t towards the homeland - by which we meant the old homeland - but further away in the opposite direction. The line from the song ‘Long is the road back to the native land...‘ just didn’t apply. Backwards and forwards formed a dialectical unity -backwards meant eastwards, in other words forwards.‘

A crazy, ragged caravan of German soldiery shuffled towards Stalin‘s city. The doctor Hans Dibold joined the traffic when his field hospital came under attack from the west. It was a nightmare journey that ended for him with a kind of glimpse of the apocalypse.

We had put on a few dressings when Grosch and Bellowitsch came up with their ambulances; the bodies were shot away, but the engines and chassis were still whole. Bellowitsch, always serious, calmly asked: ‘Where to?‘

To Gumrak.‘

Bellowitsch was a Viennese workman. He had saved many hundreds of soldiers, had driven them through fire and enemy troops to the dressing station, and had had no qualms about pointing his gun at a German officer who tried to stop him. Nor was he at a loss for an answer when a hospital doctor snarled at him one night: ‘Why didn‘t you bring in the wounded earlier?‘ ‘Beg to report, sir, that they were not wounded any earlier.‘

Under Russian rifle-fire from thirty paces and despite two shot-up tyres, Bellowitsch turned his ambulance round in the bog and brought the wounded - head and abdominal cases - safely back. And so he drove this time too. He, Grosch, and Strohbach came once more into Stalingrad to get their last orders. I never saw them again, never shall see them, and shall never forget them.

When the ambulances had driven off I stood freezing in front of the bunker. An orderly hastened up: ‘Come quickly to Major X.’ He resided some hundred yards or so away, but I had never been to him, he had always come to us. I went in. A shell splinter had shattered the window and split open the knee of a fair-haired Russian girl who was sitting on a bunk. Her trouser leg was in shreds, the knee-cap gleamed like ivory, fluid was dripping from the wound, and the thighbone gaped through. The woman whimpered as she nursed her white thigh. I put it in splints and bandaged it as best I could, and had no time to wonder where this woman had come from.

After a night spent between Pitomnik and Bolshaya Rossoshka we occupied quarters in one of the many so-called ‘death ravines‘. Russian infantry advanced towards us slowly over the undulating ground to the west and northwest. Late in the afternoon things grew quieter. During the night I was to get the last wounded out of Bolshaya Rossoshka. From an enormous derelict barn we picked up all who were left, while the divisional doctor Andreesen nervously paced to and fro, and the usual Russian plane dropped its flares and small bombs. On the way back I was asked to take an anti-tank gun in tow. I refused, saying: ‘I’ve got wounded on board.‘ Then the diesel truck got stuck in the snow. Tanks and assault guns passed us, going eastward.‘We‘ve got wounded inside.‘ No one would take us along.

Our driver went off to get a tractor from a nearby unit. Meanwhile I remained in his cab and wrestled with sleep, for the night was very cold, the temperature being down to around minus twenty-five degrees. The wounded lay together under the awning and were in tolerable shape, but I had to climb out to avoid falling asleep. Then my feet began to bum like fire, for my boot soles were full of ice. So I climbed in again and wrestled with sleep, climbed out, could stand it no longer, climbed in and so on until our driver came with a small tractor, which hauled the truck free, and we went on to Gumrak.

At Gumrak station, outside Stalingrad, a great assembly point for the wounded had been set up. The streets were overcrowded, anyone who could move at all was making his way to the assembly point. Others were lying along the edges of the road and against rubbish heaps. As soon as they got up, the whistle of bombs and the rattle of stones sent them crouching down again.

I forced my way through to the assembly point. Our wounded men asked to be allowed to stay. We unloaded them, and they joined the hundreds of their fellow sufferers along the edges of the road. A few more were flown out from Gumrak after that.

Dibold now drove on towards Stalingrad. He knew there was a medical team, the First Company of the Medical Corps, established in a balka close to the city.

We arrived, frozen to the bone and feeling rather sorry for ourselves at the First Company ravine, entered a light and warm bunker, and were delighted to learn that there was to be horseflesh for lunch, for the First Company had been ‘mounted‘.

Clean plates, knives and forks added to the amenities. Here there was an air almost of formality. The active service men sat bolt upright and ate with decorum, but I leaned rather wearily against the earthen bank under the bunker window. The last to arrive was the senior surgeon, an elderly Berlin ear specialist. I have forgotten his name, but I still remember the photographs of his children. We enjoyed the warmth, and the hot food, which we hadn‘t had for a long time, and felt secure among our comrades.

There was a sudden whine of steel. The Berlin specialist sank back into his neighbour‘s arms. It was the senior physician, Zwack, who now held him as a mother holds her child. A bomb fragment had trepanned him cleanly right across the top of his cranium above the eyebrow. The upper part of his skull hung down behind, over the limp neck, and a thick stream of bluish-red blood slowly oozed out of the large blood vessels. The brain had spattered our clothes with fine grey sprinkles. ‘Poor fellow!‘ Zwack said softly.

My chief‘s face took on a greenish pallor, he gasped for air and cried: ‘I’m choking!‘ A transverse blow had knocked in several of his ribs. Oxygen and caffeine eased his breathing. That was his fourth wound, and the third since the encirclement. We managed to fly him out, together with another man who had already lost one eye and now was wounded in the other. Of the eight people in that bunker, only Zwack and I escaped uninjured.

I had to go back to the ‘death ravine‘, and I looked around for my Volkswagen. Great caverns had been dug into the left-hand slope of the ravine. They had been stables for horses, but the animals had all been killed and eaten. These bunkers were now being used to accommodate seriously wounded cases. There was no hope for them.

I stepped out of the twilight of the bunker and walked towards the mouth of the ravine. The ground was littered with wreckage. I attempted to raise my eyes. Before me rose the dome of a white hillock. On that hillock stood three large slender crosses, marking the military cemetery. As I looked they seemed to tower endlessly into the clear grey sky; they were gently quivering as though alive.

That place was no longer Gonchara. The place where crosses are alive is Golgotha: the end.

By 19 January the Kessel had been reduced to half its original size. The dead of the Sixth Army were uncountable, and the living were being compressed into an ever-smaller space. And with every short advance, the Russians were overrunning abandoned German positions.

I could not find a piece of earth for my motor company just to shoot, so many of the German weapons lay on the ground, said Mikhail Alexeyev, who was an infantryman with the Russian 64th Army. As the circle was becoming smaller and smaller, the mounds of German guns grew higher and higher. So many, and so close to one another.

I was looking for a place to hide until morning, to get some sleep. There were many German positions safe, but nothing was available. I couldn’t use them, because the bodies of the German soldiers took up all the ground. They were everywhere, piled high on the fields and in the dugouts. I could find not one piece of open field nor any unoccupied dugout. There were also so many maggots because of the dead bodies. And oh, the lice, the lice.

I saw a dugout in the snow. I had warm clothing so I went in there and bumped against something very stiff. It was dark, so I couldn‘t see what it was. I thought they were sacks of something. So I made myself comfortable lying on these sacks. In the light of the morning, I saw that I was sleeping on the bodies of killed German soldiers.

Now the Russians were approaching Gumrak. Some planes were still managing to take off from here, so this airfield was the last chance any soldier had to be whisked out of the cauldron. The awful scenes that had been played out at Pitomnik were repeated - only this time, it was worse. In his post-war novel, The Forsaken Army, Heinrich Gerlach described the horror of Gumrak, where dying men crammed into train wagons to keep out of the cold.

Gumrak was nothing but a transit camp for the immense burial ground that stretched farther and farther into the steppe. There they lay, badly wounded cases or men who could not walk any further - 30 or 40 in a single wagon, wrapped in rags and bedded down on dirty straw or simply on the floorboards, keeping themselves warm by huddling together or by means of bonfires which they lit between the lines. There was no one there to attend to them, and if there had been it would not have helped them much, for the Army Staff had cancelled the 60-gram bread ration for the wounded on the grounds that those who cannot fight, shall not eat. The walking cases dragged themselves to a nearby pump to wait for the horse-drawn carts. Before the unsuspecting driver understood what was happening they would throw themselves with pocket-knives, pieces of metal, or just their bare hands onto the trembling horse and cut it to pieces, carrying away with them shreds of steaming flesh.

Before the door of one of the high goods-wagons they had made a stairway of hard frozen corpses. Then there was the soldier in front of the railway building. He lay there, weeping and begging to be taken in, clasping the sentry’s knee. The sentry shook him off, saying good-humouredly ‘No, it can’t be done - don’t make trouble.’ The next day the man was there again, lying on his side with his arms outstretched. His mop of ash-blond hair had been trodden into the snow. And frozen tears, like pearls of ice, glittered on his face.

The imminent fall of the airfield drove one German officer to take a desperate risk. This incident quickly made the rounds of the Sixth Army. Joachim Wieder, who knew the soldier, tells the story.

Our quartermaster, a young general staff officer, had suddenly disappeared. His driver, who had taken him to Gumrak airbase in his Kubelwagen, had waited in vain for his return. The lieutenant-colonel was missing. He had silently left the Stalingrad pocket, the zone of death and destruction, on his own initiative. Probably it was a mixture of nerves, fear, cowardice and the vain hope that in the general confusion he might be able to fly out and save his life, that had tempted him to desert. The commanding general had made inquiries by radio. The deserting staff officer had shown up at Army Group, claiming to have flown out on an official assignment from corps on matters of supply. Our general was wild with indignation and rage. He declared that he would have the criminal flown back into the pocket and shot before our eyes. We were all deeply depressed and anticipated with horror the terrible scene that had been announced, and that we were spared to our relief. Our quartermaster was shot outside the pocket on the spot where, in his fatal weakness, he had hoped to find the door to freedom and life.

Russian tanks rumbled onto the cratered, wreck-strewn runway of Gumrak on the morning of 22 January. Hundreds of German wounded, those who could not move, had been left behind. Many were crushed under the tracks of T-34s, or else were finished by a Russian infantryman’s bullet. There was a highway, about 8 miles (13km) long, that led from the airfield to the city. That snowy road was filled with suffering Germans. Joachim Wieder joined the tortured procession.

The dispersed, the starving, the freezing, the sick, but also those still fit for fighting, had only one objective to which they were attaching the last glimmerings of hope, and this objective was Stalingrad. In the protective walls and cellars of the ruins they might be able to find some warmth, food, rest, sleep and salvation.

And so they streamed by, the remains of the shattered and decimated formations, trains and rear echelon services, with vehicles that were being slowly dragged and pushed by wounded, sick and frostbitten men. There were emaciated figures among them, muffled in coats, rags; pitiful wrecks, painfully dragging themselves forwards, leaning on sticks and hobbling on frozen feet, wrapped in wisps of straw and strips of blankets.

Drifting along through the snowstorm, this was the wreck of the Sixth Army that had advanced to the Volga during the summer, so confident of victory. Men from all over Germany, doomed to destruction in a far-off land, mutely enduring their suffering, tottered in pitiful droves through the murderous eastern winter.

These were the same soldiers who had formerly marched through large parts of Europe as proud conquerors. Now the enemy was at their backs and death lurked everywhere.

Any one of the Russians on Wieder‘s heels might have pointed out to him that nobody had invited these proud conquerors to come to their part of Europe, and that the Germans had inflicted plenty of suffering on many thousands of entirely innocent people along the way. The men of the Sixth Army had sown death across Russia, and now they were reaping it. A hundred thousand of them had already died in the two weeks since the launch of Operation Ring. And there was a special kind of poetic justice in the fact that the final reckoning would take place inside the city that they had fought so hard to subdue, within sight of the wide river that they had travelled 1,250 miles (2,000km) to possess.

THE SQUARE OF THE FALLEN

The main square of Stalingrad was a just a short walk from the banks of the Volga. Before the Revolution, this broad open space was called Alexandrovskaya Square, after the beautiful Byzantine cathedral of St Alexander, which stood at its eastern end.

The cathedral had been demolished in the 1930s as part of Stalin‘s nationwide drive to eradicate religion, and a modern plaza had been constructed in its place. On the northern edge was a brand-new department store, the Univermag. On the opposite side was a plush 19th-century hotel, which had been a headquarters for the Red forces during the Russian Civil War. Between these two ensembles the planners of Stalingrad had created a little park with a monument to the Bolshevik dead of the Civil War. The square had been renamed in their honour: it was the Square of the Fallen Fighters. The Germans, for their part, never used the Soviet name. ‘Square of the Fallen Fighters‘ was too much of a mouthful in German, and the reference to Communist heroes was in any case rather unpalatable for Nazi ideologues. So the Germans always referred to this point on their maps as Red Square, by analogy with Moscow.

Now, in the last week of January 1943, the Soviet name was gruesomely apt, for the square was strewn with dead Germans, or with Germans who would be dead very soon. Waves of soldiers flowed like grey floodwater into the fetid cellars of the buildings around the square: the Sixth Army was retreating underground. Both able-bodied and wounded men crammed into the bowels of the city theatre, just opposite the hotel, and set up firing points in windows and doorways. Many thousands more occupied basements throughout the diminishing patch of ruins that remained in German hands. They continued to resist the Russian advance from the west, and ferocious battles were still being fought in the outhouses and machine rooms of the factory district.

But on 26 January, the Russians broke through to the Volga in the region of Mamayev Kurgan, splitting the German resistance in twain as they had planned to do from the start of Operation Ring. There were now two small Kessels, one in the north and one in the south of the city.

General Friedrich Paulus, along with his staff, was lodged in the crowded maze of rooms beneath the Univermag, in the southern Kessel. He had set up his command post in a dark, narrow little room deep inside the subterranean labyrinth. Here he had a respectable but battered desk and, behind a curtain, his camp bed.

The bed was where Paulus spent most of his time. He lay there in a mood of fatalistic apathy, expressionless apart from the nervous tic that twisted his face violently and spasmodically every few seconds. Command of the army had in effect devolved on General Arthur Schmidt, who occupied a little room across the corridor from the commander-in-chief. In this dark and monkish cell, the devoutly Nazi Schmidt perused his operational maps, issued orders, and kept a large commercial safe full of documents: the red tape of total war.

Here are some extracts from those papers. They are transcripts of radio messages which, when taken together, form a kind of collage of confusion and defeat: defensive positions are given up one by one; generals commit a soldierly kind of suicide by charging at the Russians, guns blazing; officers receive promotions - mostly posthumously - or simply vanish without trace into the maelstrom of destruction.

Daily Bulletin from Don Headquarters, Jan 24th.

Romanian 1st Division and Romanian 20th Division fought to the last with distinction, shoulder to shoulder with their German comrades. Their deeds deserve to be singled out in the history of this unique battle ...

Morning bulletin from Don Headquarters, Jan 25th.

Swastika flag hoisted on tallest building in the town centre, last battle to be fought under this symbol ...

Intelligence report, January 26th.

4th Corps south of Tsaritsa collapsing in face of enemy army’s superior numbers. Last report from there received 07.00 hours, that Generals Pfeffer, von Hartmann, Stempel and Colonel Crome with few men are making a stand on the right-hand side of the railway embankment, firing into the Russians who are advancing in large numbers ...

General von Hartmann, Commander 71st Infantry Division killed at 08.00 hours by a bullet through the head during close combat. General von Dresser, Commander 297th Division, overrun by Russians in his command post at noon on January 25th, presumably taken prisoner ...

Daily bulletin, January 26th.

Croatian 369th Infantry Regiment participated in the fighting around Stalingrad with 1st Croatian Artillery Division, and distinguished itself outstandingly. Heavy enemy artillery fire over the entire town area. Defence of same massively hampered because of 30,000 40,000 unattended wounded and scattered personnel. Energetic leaders making every effort to form units out of scattered personnel, and are fighting alongside them offering front-line resistance. Apart from a few scraps, all rations have been used up ...

German Gold Cross awarded to Major-General Wulz ...

January 26th.

Don Headquarters. Request posthumous promotion for Lieutenant-General Hauptmann, Commander of the 71st Infantry Division, whose outstanding conduct was a shining example, and who fell today in close combat. Signed, Paulus ...

January 27th.

We are keeping the flag flying to the last. Greetings to Nienhagen and Leipzig. Signed, Lieutenant General Schmidt...

January 29th.

Don Headquarters. Lieutenant Antlebert Zuhlenkamphs, nephew of General von Seydlitz-Kurzbach, killed in action. Please notify next of kin.

Also in Schmidt’s safe was a message from Paulus to Hitler in which, at long last, he pleads for the right to give up the struggle.

Troops are without ammunition and food, wrote Paulus. We have contact with some elements of six divisions only. There are signs of disintegration on the southern, western and northern fronts. Unified command is no longer possible. Little change on the eastern side. We have 18,000 wounded who are without any kind of bandages or medicines at all. The 44th, 76th, 100th, 305th and 384th divisions have been annihilated. As a result of strong incursions the front has been tom open. Firing points and shelter are available only inside the city. Collapse is inevitable. The army requests permission to surrender so as to save the lives of those that remain.

Hitler categorically refused once more. He had one last dramatic set piece in mind. The tenth anniversary of the establishment of the Nazi regime was coming up, four days hence. This was an important occasion for Hitler personally, and it was a fine opportunity to make some propaganda capital out of the situation at Stalingrad. But for this piece of theatre to work, Hitler needed the army to continue the struggle until then - to remain on stage, as it were, until Hitler himself decided it was time to bring down the curtain. The centrepiece of the anniversary celebration was a speech, which Hitler delegated to his corpulent sidekick Hermann Goring. The Reichsmarschall knew his master‘s mind, and made an address that was intended to lay the foundations of a National-Socialist legend. It was broadcast to the nation on the evening of 30 January.

The speech was a dreadful piece of faux-knightly bombast, a classic piece of Nazi rhetoric, in fact. ‘There will come a day when future generations will speak with pride of the struggle of the Sixth Army,‘ intoned Goring. Then, placing Stalingrad alongside other great battles in the annals of German feats of arms, he said:

Every German will one day speak in solemn awe of this battle, and will recall that in spite of everything the foundation of Germany’s victory was laid here. They will speak of a Langemarck of daring, an Alcazar of tenacity, a Narvik of courage, and a Stalingrad of sacrifice. In days to come it will be said thus: when you come home to Germany, tell them that you have seen us lying at Stalingrad, as the rule of honour and the conduct of war have ordained that we must do, for Germany’s sake. It may sound harsh to say that a soldier has to lay down his life at Stalingrad, in the deserts of Africa or in the icy wastelands of the North, but if we soldiers are not prepared to risk our lives, then we would do better to get ourselves to a monastery.

The speech was listened to with sullen humour or impotent rage in the cellars of Stalingrad. Many remarked ruefully on the irony that the fattest man in the entire Reich had the gall to place himself alongside the starving wretches of the Sixth Army. Others screamed at the radio where they lay wounded, or shouted for it to be turned off One unit stranded in the northern pocket sent a curt radio message to Berlin. ‘We can do without premature funeral orations,‘ it said.

THE BROKEN-HEARTED FIELD MARSHAL

But the oration was not all that premature, as the death of the Sixth Army was imminent. Russian troops appeared on the fringes of the Square of the Fallen Fighters on Hitler’s big anniversary. Crossfire sputtered and cracked around the Univermag and the theatre. But the gun battles that day were almost desultory. The Germans knew it was all over, and individual units were unilaterally laying down their arms and surrendering.

That same day, having sent his anniversary congratulations to Hitler (‘The swastika still flies over Stalingrad’ said the message) Paulus gave his permission for talks to be held with representatives of the Red Army, whose soldiers were now gathering on the other side of the square. While the formalities of capitulation were being set in train, a message came in from Führer headquarters. It was a promotion for Paulus: he had been raised to the rank of field marshal. Paulus knew what this parting message from Hitler meant: in all German history, no field marshal had ever been taken prisoner. The award of the baton invited Paulus to carry out a death sentence on himself, and so add a pleasingly tragic grace-note to the future legend of Stalingrad.

Paulus was possibly mulling this over on the morning of 31 January, when the Russian envoys arrived to discuss surrender terms. These first emissaries were fairly low-ranking: Lieutenant Colonel Vinokur, who was a commissar with General Shumilov’s 64th Army, and First Lieutenant Fyodor Ilchenko. A more senior delegation led by Generals Laskin and Mutin soon followed. It arrived on the square while Vinokur and Ilchenko were still inside the Univermag. Leaving General Laskin behind for now, Mutin took some men and headed boldly across the square.

We walked over to the department-store building where the headquarters of the German Sixth Army was located. As we approached it, we saw that the muzzles of artillery pieces and rifles were poking out of all the windows and doors on every floor, including the basements, pointing at the opposite side of the street that ran past the department store, where soldiers of our 38th Brigade were lying on the ground with their weapons aimed at the enemy.

All this enemy weaponry had been blazing away only fifteen minutes before our arrival, and was now bristling, ready to start firing again at any moment. In the rest of the city, only five or six hundred metres from the department store, the Germans were continuing to fire from all types of weapon. There was a ceaseless rumble of cannon.

Pavel Lyamov, an intelligence officer with the 64th Army, was with General Mutin. He vividly recalled their descent into the eerie underworld of the Univermag.

Nobody was shooting at us, said Lyamov. At the entrance to the basement stood five tall SS officers with swastikas on their sleeves, sub-machineguns around their necks and pistols on their belts. It was sleeting. Individual groups of our scouts had taken up positions on top of smashed German tanks and cars, and on the walls of ruined buildings. All was quiet, except for the sound of gunfire coming from the north.

It felt as if they were expecting us. The guard checked our credentials, and on his signal a young SS colonel came out, introducing himself as Colonel Adam, an aide of Field Marshal von Paulus. He asked all four of us to follow him into the basement. It was dark. We entered the basement via a ramp. Our general was walking behind Colonel Adam, followed by the Army’s head of reconnaissance, the interpreter and myself. At the bottom of the ramp we turned right and went down a narrow corridor, our way lit by Colonel Adam. We hadn’t thought to bring along any torches.

In the basement there was a deathly quiet. After about 80 metres, we all turned to the right again and entered an intercommunicating room lit by lamps. What was the first thing we saw? Straight in front of us there hung a dark-pink velvet banner with fascist swastikas on the bottom, to the left stood a round table, the top of which was entirely covered by a Nazi swastika. Behind the table stood a tall general with an iron cross. The generals swapped credentials.

The German general, Rosske, announced that the Führer had conferred on Colonel-General von Paulus the highest German military rank of field marshal, evidently hoping that our delegation would be deeply impressed by this and express hearty congratulations. But no one spoke.

Mutin, unlike Lyamov, was not unnerved by the devilry of the Nazi decor, nor was he amused by the smug Smalltalk of the German officers. It was the gaunt spectres milling around in the shadows that troubled him.

The Germans started shouting and kicking up a racket. They shoved each other aside to make way for us. Colonel Adam had to go to the front and lead us. We walked along a narrow, dirty corridor, poorly lit with lamps made out of artillery-shell cases, past rows of Germans standing to either side.

The room that Colonel Adam led us to was poorly lit by a dying candle and a dim lamp. The room was a mess: suitcases, clothes and furniture were strewn about all over the place. All the officers under Lieutenant-General Schmidt and Major-General Rosske, somewhat nonplussed by the appearance of our delegation, stood up and then introduced themselves. We, in turn, then introduced ourselves as representatives of the front commander General Rokossovsky, and said that we were authorized to negotiate the capitulation.

Our names were known to them through their intelligence, and a kind of hiss ran round when they heard my name. ‘Commissar, commissar, commissar,’/ and they started staring at me as if looking for my devil’s horns and tail.

When we entered the headquarters room, there were Lieutenant-Colonel Vinokur and First Lieutenant Ilchenko. I straight away instructed Ilchenko to expedite the installation of a telephone so that we could communicate with our army’s headquarters, and then to take advantage of the bewilderment and confusion in the enemy’s camp to disarm the German headquarters guards and replace them with our own guards. Comrade Ilchenko left the room immediately to carry out the order, while Vinokur stayed behind with us.

From the outset, General Schmidt came across as an inveterate fascist. All his clothes were ironed and polished to a sparkle, he was clean-shaven, his hair was combed and greased, he had a little black Hitler moustache, thin lips and small, black, round eyes that kept darting about, and his pronunciation was clipped like a dog’s bark. Outwardly, he was all pomposity, but on the inside he was trembling in some kind of agony, as if in his death throes, waiting for something terrible to happen. Colonel Adam was very quiet, and did not join in the conversation. He was taciturn and worried-looking, and as soon as the introductions were out of the way he went off to his room on the pretext of gathering some things that he needed.

Colonel Adam was in fact darting backwards and forwards to the dark corner where Paulus lay waiting. His job was to keep the field marshal informed of developments in the other room. Paulus had made plans for his own personal surrender, which were about to be put before the Russians.

We presented the printed ultimatum signed by Generals Voronov and Rokossovsky, and asked that all personal weapons be handed over, continued Mutin. Our demand was carried out immediately, with no resistance. Everyone in the room handed over their firearms and removed their daggers from their belts. Thus began the disarming of German forces of the entire southern group in Stalingrad.

In response to our delegation’s demand to be taken at once to Field Marshal von Paulus, Lieutenant-General Schmidt said that von Paulus was in a separate room, that he was unwell, and that he was no longer in command of the army, as it had been broken up into independent combat groups. Von Paulus himself was now a ‘private citizen’, and he, Chief of Staff Lieutenant-General Schmidt, would be conducting the negotiations.

We insisted that Lieutenant-General Schmidt notify Field Marshal von Paulus of the arrival of our delegation for negotiations, and that von Paulus himself receive us and sign the order for the capitulation of the German forces. Lieutenant-General Schmidt immediately carried out our demand, and reported everything to von Paulus.

Von Paulus confirmed, through General Schmidt, that he was no longer in command of the army, that he was a private citizen and would therefore not sign the capitulation order. He refused to receive our delegation, but asked that, as a field marshal, he be personally taken prisoner and escorted by one of our generals.

To keep the negotiations going, our delegation then told General Schmidt to issue an order for the immediate cessation of resistance and the complete capitulation of the German grouping. Fallen Warriors‘ Square was designated the place where weapons and equipment were to be surrendered and prisoners received.

All these preliminary capitulation terms were accepted by the German command, but with the following conditions. Firstly, the delegation was not to interrogate Field Marshal von Paulus in any way, since he would supply information on military arrangements only to Colonel-General Rokossovsky; secondly, von Paulus’s safety had to be guaranteed, to ensure that he would not be attacked and killed en route or when leaving the building; thirdly, even though von Paulus was a ‘private citizen’, his soldiers were not to be disarmed until he had left the building, and once he had left he was not to be held responsible for the actions of his subordinates. General Schmidt reported this last request in an emotional tone, and then added that ‘it would break the Field Marshal’s heart to see his soldiers disarmed.’

The Russians chose not to be moved by the delicacy of the German commander’s feelings. They waited for General Laskin to come over before proceeding to the next stage of this strange rite, which was the formal arrest of Paulus.

General Laskin arrived at around 08.40, and took command of our delegation. We then went to Field Marshal von Paulus’s room, where we found him dressed in an unbuttoned greatcoat and pacing up and down the room. It was partitioned off by a chest of drawers. A desk stood by a basement window looking onto the department store’s yard, and behind the chest of drawers, in the dark part of the room, there was a bed.

When he saw us, Field Marshal von Paulus stopped in his tracks but did not say anything. General Laskin gave his name and rank, declared von Paulus a prisoner, and told him to surrender his personal weapons. Field Marshal von Paulus then gave his own name and rank, and stated that he was surrendering to Soviet forces, that he did not have any personal weapons on him and his aide-de-camp had his pistol, and that he had only been made a field marshal on January 30th, and had not yet received his new uniform -which was why he was dressed in the uniform of a colonel-general. He went on to say that he would not now have much use for the new uniform.

General Laskin then told the field marshal to present his army-commander identification card. In response, von Paulus pulled a soldier’s card from his tunic pocket and handed it to General Laskin, stating that all he had was his soldier’s card, and that he didn’t have any other documents attesting to his identity as army commander. General Laskin, having checked the soldier’s card through the interpreter Stepanov, returned it to von Paulus.

General Laskin and I then briefly discussed the situation and decided to search Field Marshal von Paulus. The search was carried out by myself. I carefully checked all his clothes and pockets. The reason this had to be done was that some German generals had committed suicide rather than be taken prisoner. So we had to take all precautions to stop von Paulus doing the same thing. Although he seemed a little put out by the search, he did not offer any resistance or objection. And then, when General Laskin asked von Paulus whether he was ill, he replied that he was well but had been affected by the poor diet and the long-drawn-out, agonizing experience of the ignominious capitulation of his army.

And then he took out of his trouser pocket some small cubes of baked bread, like we used to make with oil. He showed them to us and said: ‘A hundred and fifty grams a day - that’s all I’ve had to eat for many days now. I’ve been sharing my starvation rations with my soldiers, who only get fifty grams a day.’

With that contradictory and self-serving admission - that he got three times the rations of his ravenous men - Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus, commander-in-chief of the Sixth Army, became a Russian prisoner of war.

TRIUMPH AND DISASTER

Afzal Khairutdinov was an 18-year-old infantryman from Kazakhstan. Like all the Red Army men in Stalingrad, he was aware that the day of victory had arrived. ‘On January 31st the character of the fighting changed completely, as the Germans were completely demoralized.‘ It was only a matter of a few weeks since he and his classmates had been plucked from their military academy and sent to fight in the city. Khairutdinov had been attached to the 173rd Rifle Division. In less a month he had gained more knowledge of practical soldiering than he could have hoped to acquire in a decade of attendance at the training school. Now he was daring to wish that his luck would hold, and that he would live to see the end of the battle - and after that, the end of the war.

But today there was still work to be done.

On that morning the frosts were strong - it was 35 or 40 degrees below zero. The remains of our battalion were gathered together and formed into two units, one of which was put under my command. There were very few officers left. The commander of our platoon had already been wounded.

The lieutenant in charge of our company ordered us to blockade a building about 150 metres away from our position and to clear it of Germans. The building was in ruins, and the windows were empty, like eye sockets. We advanced. We went in single file, one behind the other. We began to notice packages on the snow, supplies that had been dropped on German positions during the night. We picked one up: it was frozen loaves of bread. We gathered together a few of these packets.

We could see the heads of some Germans bobbing in and out of view at the dead windows. They did not shoot. We were walking upright in broad daylight, so I suppose we were not expecting them to shoot. Their situation was hopeless, after all. We approached a little niche on the front of the building, where once there must have been a front door. The shadow of a soldier passed across it. I shouted: ‘Kamerad, komm!’ After a few shouts there appeared the dirty, stubbly face of a crawling soldier. We again called to him to come out to us. After a little hesitation he stood up. I told the lads not to point their guns at him. I held out the brick of bread that we had picked up. He grew bolder and came nearer, grabbed the bread and straight away began to gnaw at it. Then a second soldier came. We asked them: are there many of you down there? ‘Oh, lots and lots, ’ came the answer. This surprised us. We gave them all the bread that we had picked up and told them to go back down into the basement and come out with all the others. Then we waited.

After about five minutes the same two came back with three or four others. We said: is this all of you? They replied that there were others, but they were afraid to come out -especially the officers. So we sent this party back too and said that everybody had to come out. A long time passed. We prepared for the worst. We could hear dull shots coming from the basement. Something was going on down there. Then we heard noises getting nearer, talking. First out were our new acquaintances, and many more came behind them. We saw that they were carrying a wounded officer - he was tied up and lying on a stretcher. We asked: why has he been tied up? It turned out that he had woken up to see the soldiers preparing to give themselves up, and had drawn his pistol to threaten them. Someone had shot him in the leg. Then they all tied him up.

They all had their hands up and were unarmed. We asked: where are your guns. ‘Down there,’ they said. We told them all to go back (apart from the officers - there were some of them too) and to come back with their weapons. They very quickly did as we asked and piled up their guns in the place we told them to. We were astonished by how many people came out of that basement. A whole battalion at least! Around that time our own officers turned up and began to organize the process of taking them prisoner.

Our commander came over to us and said: Well done, you good lads. I have just one more job for you today. Go and clean out that building across the square, and then you can relax.‘

It was about two in the afternoon by now. It was extremely cold - so much so that my tommy-gun would barely fire because the grease had frozen. I had to swap it for a different one; the lieutenant gave me his. We went forward to carry out the order. We went about it the same way as before: single file, one behind the other, me in front.

Suddenly we realized that we were in a minefield. Here and there we could see the tiny wooden crosses poking above the ground. This meant there were anti-infantry mines, the kind we called ‘frogs‘. If you touched the wire and set one off it jumped up in the air and exploded. They could take out everything in a four- or five-metre radius. We stopped in our tracks, and discussed what would be for the best: to go on or to turn back. The lads all said: ‘We‘ve seen this before, let‘s go on. Going back is just as dangerous.‘

No Germans were shooting at us, and there were none to be seen. I began to take forward steps, slowly and carefully. The lads (there were six or seven of them) followed in my steps. I should say that the square was full of ruts and holes. There were abandoned rifles lying around on the ground, helmets, all kinds of kit, bits of bricks, pieces of broken equipment. It was very hard to make progress. I had not gone ten steps when I stumbled and fell forwards. Before I could straighten up I heard the deafening sound of a mine exploding three or four metres behind me. In that instant I felt a hard blow in my right shoulder, and something wet on my back. I knew it was blood, but strangely, I felt no pain. I glanced behind me in time to see my lads falling down -some of them frontways, others onto their backs. It was sickening. A mine must have gone off at their feet. I managed to see not only my lads as they went down, but also all the sharp and jagged objects on the ground around me. I managed not so much to fall as slowly lower myself onto the snow. I remember nothing more. I lost consciousness.

Khairutdinov lay unconscious for some hours. It was pitch black by the time he came round, and even colder.

I woke up with the sensation that someone was pulling me about, rifling through my pockets and taking away my documents. Then I heard a voice: ‘Hey, this one‘s alive, he‘s moving.‘ A second person came close. I was slowly coming round, and with great difficulty I opened my eyes. I could see the clear night sky and the twinkling stars. I felt a dreadful pain in my neck and my right shoulder; I felt weak. The medic, leaning over me in the darkness, was trying to find out whereabouts I was wounded. He was saying: ‘Where is he hurt? His arms and legs are in one piece, his head too. I see no blood.‘ Seeing that I had opened my eyes he asked me: ‘Where were you hit?‘ I tried to answer but I could not open my mouth or make a sound. I was completely numb. He could see me trying, and waited. ‘Where then, where, where?‘ At long last I forced out some kind of sound. The medics were prodding me all over: my face, my nose, the top of my head. I managed to pronounce the word ‘neck‘. One of them shoved his hand down my collar and brought it back out covered in blood. ‘There it is!‘

The medic got a pair of scissors and cut all the way up the sleeve of my quilted jacket (I wasn’t wearing an overcoat). He cut as far as the place where I was wounded. Then he put a field dressing on the wound and bandaged it. After that he bound up the sleeve of my jacket with some wire and put me on a sled.

I asked them to help my lads. ‘They are just here,‘ I say. One of the medics showed me a wedge of Red Army pay books and said: ‘There is no one here who needs our help. They are all goners. You are the only one we found alive.’ I was horrified. All my boys were dead.

As for me, I was dragged across the bumpy, shell-pocked square. It was pure torture. Though the field hospital where they were taking me was not far away, they had to take me over all kinds of obstacles and rough ground to get there. At one point they tugged at the rope as we went over a shell hole and the sled shot out from underneath me. I ended up in a hole full of snow. They swore out loud, hauled me out and told me to hold on tight to the edge of the sled, then ... the same thing happened again. My hands were freezing: I couldn’t hold onto anything. Finally they dragged me to a large canvas tent and put me down on straw near the entrance to the operating room.

Inside the tent there was a surgeon and his team of helpers. I waited there till deep into the night, and all the time there were operations going on. A helper would come out from time to time and pick out the most badly wounded person, who would then become the next to go in. As the rest of us waited for our turn, we could hear the screams and groans of the wounded being operated on without any anaesthetic. It made you shudder.

I was one of the last. They led me in and sat me down on a chair. One of the helpers held me very tightly. The doctor opened up the entry wound with a kind of pair of scissors, rooted around in there and found a piece of shrapnel - which he pulled out and showed to me. ‘That’s what got you,‘ he said, and tossed it into a big bowl.

Afzal Khairutdinov was lucky. He had got the perfect wound, the one that less enthusiastic soldiers than Afzal dream of: something bad enough to put you out of action, but not disfiguring and not permanently crippling. Thousands of Germans had been praying for such an injury for months - they called it the Heimschuss, the ‘home shot’ - but now it was too late. Captivity was the best remaining option for them.

Captivity, or a soldier‘s death. In the centre of Stalingrad, not all the Germans had heard of the general surrender, as the Russians were discovering. Ivan Vakurov was with the 173rd Rifles, like Khairutdinov. On 31 January he too was detailed to round up prisoners, but he had an additional task: to raise the red flag on a tall building known as the ‘Black House‘ near the so-called Nyeftesindikat factory on the banks of the river. Inconveniently, there were still Germans inside it. Right at the last, Vakurov‘s weary riflemen were going to have to employ the tried and tested street-fighting tactic.

The storming of the house began in the morning, after an artillery bombardment. The Germans, hiding behind the thick stone walls, were firing from all the windows and out of the basement. The storm groups moved forwards in short hops, covering each other‘s approach with gunfire. Lieutenant Rostovtsev was first to get to the doorway of the Black House.

Using grenades and machineguns we carved out a path up the stairs. Right behind Rostovtsev were Lieutenant Titov, Sergeant Kozachuk, and infantrymen Khoroshev, Zapolyansky and Matveyev. There was a struggle on the staircase landing at the second floor, and an enemy bullet felled Lieutenant Rostovtsev. Sergeant Zhernov took his place. While the battle continued on the second floor, more storm groups burst into the building. There were battles in every corner of the house.

Khoroshev covered Matveyev as he climbed up into the attic, found a way out onto the roof, and attached the flag to the chimneystack. All the fighters attacking the Nyeftesindikat saw it, and we heard their loud ‘hurrah‘. They pushed forwards more strongly after that. The enemy‘s resistance weakened and soon ceased altogether. More than 700 prisoners were taken.

Elements of the 173rd Rifles reached the river. Some of them were sure the battle for the city was now over, and were shooting their guns into the air in celebration. Then they turned to their right and headed south, towards the town centre. Everywhere Germans were giving up and emerging from cellars with their hands up. Vakurov and his men were expecting at any moment to happen on the men of the 65th Army as they pushed north. But there remained one last hurdle for them along the way.

The regiments of our division cleaned out Kirov Street, Sovetskaya Street, Parkhomenko Street and Pushkin Street. It was not until we reached Ninth of January Street that we encountered strong resistance. The enemy had dug himself in inside the building of the State Bank, and was directing machinegun fire at us.

A company under the command of Sergeant Sklyerov found a way into the Bank via holes in the walls, and forced their way to the stairwell. There was a short skirmish, which resulted in our taking 70 Germans prisoner. Private Gorbatko raised the red flag above the State Bank building.

We had not yet cooled down after the tension of that heated battle when we heard more shots coming from the street below. Gorbatko stuck his head out of the window, and shouting above the gunfire he called out: ‘It‘s our lot! We‘ve joined up!‘

That is how the 173rd Division connected with the forward units coming from the south. It was decided to commemorate the moment in an official document.

This is what the document said: ‘We, the undersigned, Major Vasily Ivanovich Telegin and Captain Nikolai Nikitovich Remizov on the one hand, and Major Ivan Pavlovich Akhmatov and Senior Lieutenant Ivan Yefimovich Titov on the other, have drawn up this deed in testimony of the fact that our respective units, acting in Stalingrad from two directions, defeated the enemy in battle and joined forces on Ninth of January Street, where we exchanged greetings.‘

With that little piece of pomp the fighting in the city centre came to a stop. However, there was still a war going on in the factories. One of the last outposts of the Kessel was centred on the large brick building of Workshop No. 32 of the Barricades Factory. Here a handful of Germans had been fighting a desperate battle all through the last week of January. They were not in contact with Paulus, and had not heard the news when he gave himself up. Probably they would have fought on anyway: Workshop No. 32 was the alamo of the eastern front.

The Russians, for their part, could not flush these Germans out or make them surrender. A kind of unstoppable momentum was leading Russian commanders to throw more and more men at the workshop. A group of Russian infantrymen was holed up somewhere inside the building, and had been there for some days, but many of their comrades had been killed to gain that foothold. Now they were cut off from HQ, and the telephone line was broken.

Some junior officers at HQ were incensed that their officers were employing the wasteful tactic of full-frontal assault at a time when the battle for the city was clearly drawing to a close. One of the angry young men was Alexander Lukash. He was with the naval infantry of the 92nd Independent Rifle Brigade, the tough band of naval infantrymen who had fought in the grain elevator during the autumn. He was convinced that the time for suicidal bravery was past. Lukash was not inclined to sacrifice himself or his men for the sake of some colonel’s arbitrary schedule. Yet orders were orders in the Red Army, just as surely as they were in the Wehrmacht. Lukash‘s orders were to get inside the workshop and make contact with the stranded group, to end the German resistance, and to do it right away.

I began to object that it was impossible to do that in broad daylight, but the brigade commander Yelin coarsely interrupted me and demanded that I carry out my orders immediately. I put together a team of 15 men - all volunteers, of course. Among them were platoon commander Semyonov and company commander Lieutenant Ageyev. Rukavtsov was already in a forward position with a group of scouts.

Naturally, we did not begin the attack in daylight, but lay in the neutral zone under enemy fire until darkness fell. It was night when we made our way into the workshop building. The scene inside was indescribable. Bodies, nothing but dead bodies, everywhere you looked. There were wounded who lay there bleeding. No one was going to their aid. There was no ammunition and nothing to eat or drink. The only place there was anyone alive was the washroom: tired, hungry men. On the command of one of the junior commissars, they were occasionally shouting ‘Hurrah‘ - and that alone was giving the Germans a fright.

The commissar gave me a quick report on the situation, but I could see for myself what was happening. That night, under cover of darkness, we attacked the other end of the workshop and made some progress, but in the morning the Germans forced us back to the washroom area. Medical instructor Kolomitsev took some of the scouts and they gave what first aid they could to the wounded. All the food we had was shared out.

That morning the scouts found the break in the cable that was preventing us making contact with HQ. It was right by the telephone itself. The line was re-connected, and I personally reported to Yelin all I had seen, and proposed to bring the men out right away as only 20 or so were still alive. Yelin did not believe me, and told me once more to carry out my orders. A few minutes later contact was lost again.

We remained in the workshop for several days. We fought till we were ready to drop. At one point we were grabbing some sleep in a toilet cubicle when we were woken by a powerful explosion. There was dust everywhere, and bits of grit and brick flying through the air. The Germans had blown up the roof of the workshop, and what was left of our brigade was now buried under concrete.

This crudely effective blow put paid to Lukash‘s attack. He was not badly hurt himself, but many of his men were killed. There were not enough men left alive in the washroom to carry on the fight. Lukash did not know it, but by now Paulus and the southern pocket had capitulated. His men and his enemy were among the very few soldiers in Stalingrad who were fighting. Still seething with anger at his own leaders, Lukash decided to call off the offensive and return to base.

That same night three of us - me and two scouts - made our way back to brigade HQ. We were hungry and worn out. We were not the only survivors, but it nevertheless felt like a miracle that we were still alive. About 15 men made it back from the workshop over a period of time.

Brigade commander Yelin gave us a cold reception. He said he was sure we were all dead. This was an affront not just to me, but to all those fine sailors who had pointlessly laid down their lives. That their brigade commander should so glibly write them off, the living as well as the dead! That was the tragic conclusion of the battle for Workshop No. 32.

And that, more or less, was also the conclusion of the Battle of Stalingrad. The last few pockets of German resistance, including the men in Workshop No. 32, laid down their arms a few hours later, on 2 February.

By the Russian way of reckoning, the Battle of Stalingrad had begun on 17 July, when the as yet unblooded 62nd Army first exchanged fire with the Sixth Army. That initial encounter had been a running battle on the open, sun-drenched steppe, where the Germans were bowling towards the city like an unstoppable train. Precisely 200 days had passed since then, and the final shots were exchanged between men of the same two armies. Only now they fought in the cold, static ruins of the Barricades Factory - a few hundred yards from the indifferent river.

Alexander Lukash, recovering at his command post, must have been close enough to hear the crack of the last bullet fired in the battle of Stalingrad. He was waiting for it. He had a personal errand to run once the guns fell silent; then he could put aside his rage.

We went back into Workshop No. 32, hoping to find someone alive. But we found nothing but corpses. On that raw, snowy ground lay the bravest of the brave, the very best sailors and officers we had. Senior Lieutenant Semyonov died there, and so did Lieutenant Ageyev.

Yet that day, February 2nd 1943, was the most joyful and happy day of my life. It was joyful first and foremost because we had won, we had defended the city of Stalingrad and held on to it. But I was happy too because I had come out of that inferno alive, and I was not the only one who was celebrating. I saw men weep, young ones and grey-haired elderly ones. Everywhere people were embracing and kissing each other. How sad that so many did not live to see that day.

That is why I bow my head before those who fought on the banks of the Volga and sacrificed the most precious thing they had - their life.