The Principles of Ship Design

WARSHIPS WERE THE PRODUCTS of a series of compromises. In the seventeenth century, and indeed throughout the era of sailing navies, shipbuilders had to balance the requirement for a heavy armament against sailing qualities; particularly from the 1650s to the early 1670s, the British often over-gunned their ships as a matter of deliberate policy, with an adverse effect on the hull’s centre of gravity and a consequent loss of speed and stability.1 Ships were also the homes of men, many hundreds of men in the case of a First or Second rate, so space had to be found for their accommodation, stores and provisions. Put simply, a ship that carried more of everything could stay at sea longer, but to do so, it would need to carry a smaller armament; a ship that could not properly repair, feed or water itself had to return to port within a finite timespan, but could carry the maximum number of guns that the hull would bear. Experience built up over many generations provided answers to these questions, but the answers lay in the hands not only of the experts, but also of the accountants. Warships have always been expensive, and ultimately, cost dictated their size, power, and number. The hull alone of the Sovereign of 1637 had cost almost £30,000, which was exceptional; forty years later the hull of a new First Rate was estimated to cost about £22,000. By that time, the hulls of Third Rates were costing at least £8,000. Fitting out the First Rate took its cost to an estimated £33,390, with the Third Rate costing just over £15,000. The cost of wages, victuals, powder, stores and wear and tear for six months would push up the cost of the First Rate by another £12,888, and that of the Third by £7,301.2 Unlike a fortress, which cost about the same to build, a First Rate could be destroyed in a matter of minutes (as was the Royal James in 1672), taking with her more guns than any army of the time had in the field. ‘Great ships’ were thus a phenomenally expensive and high-risk investment for the state, at the very limits of the technology and logistics of their day.3

Warships were expensive in other ways, too. They took many months to build, and required huge quantities of timber, especially English oak. Given the amount invested in them, the difficulties inherent in their construction and the ability of shipwrights to constantly modify them to keep pace with changing patterns of ship design, it was hardly surprising that the largest ships stayed in service for many years. The Prince of 1610 and Sovereign of 1637 fought in battles when they were well over half a century old, and several Third and even Fourth Rates lasted just as long. This was a significant difference between the British, Dutch and French navies, for in the two continental services it was rare for a large ship to last much longer than twenty or thirty years.4 Thus one of the most fundamental principles dictating the design of a British warship was the unspoken assumption that a ship had to be built to survive for as long as possible.

The Royal Katherine of 1664. Initially considered a serious design failure, she eventually became a popular ship with a long and proud record in battle.

(WILLEM VAN DE VELDE THE YOUNGER; FRANK FOX COLLECTION)

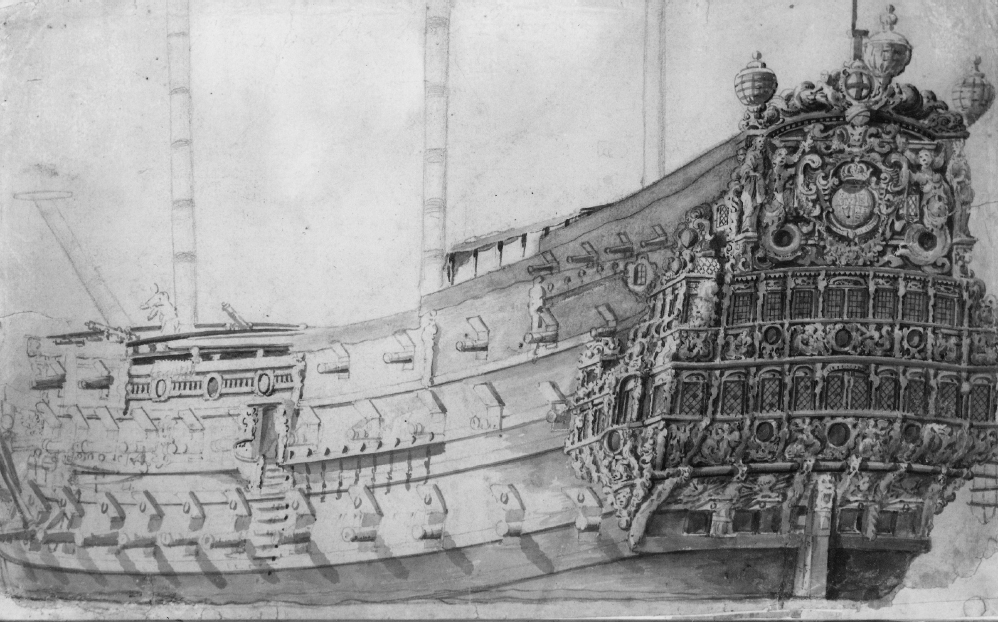

Though modelled on no particular ship, this Van de Velde drawing of an English-style three decker gives a good impression of the formidable power of the broadside.

(© TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

THE BROADSIDE

By the middle of the seventeenth century, all British warships carried most of their armament on their sides. Ships still had a few guns in the bow or the stern, which were used primarily when pursuing or the pursued, but the emphasis was overwhelmingly on the broadside gun battery, which had proved to be the ideal configuration for long, narrow sailing ships. Except on the relatively rare occasions when a ship had to fight on both sides simultaneously (which usually occurred when that ship was in serious trouble), only one side would be engaged, and it was not uncommon for all the firing to take place, and all the damage to be sustained, on that side alone. The weight of the armament was one of the key factors determining the dimensions of the ship and the size and nature of the timbers used in her construction. By the 1680s, the batteries of First and Second Rates weighed over 165 tons, those of the larger Thirds about 130, those of Fourths about sixty; this gave a ratio of weight of guns carried to ship’s tonnage of 1:8 or 1:9.5 Ships also had to carry the weight of shot that these batteries could deliver, based on the traditional allocation of forty rounds’ worth of powder and shot to each ship.6 The broadside of the Britannia, the huge First Rate built in the 1680s, could fire over 1,000 pounds of shot, while that of the old Fourth Rate Centurion could fire about 300.

These weights increased through the course of the period, both reflecting and causing the steady increase in the sizes of warships of all rates. Thus an older Third Rate, the Monck of 1659, carried a battery weighing eighty tons and could deliver 429 pounds weight of shot, but the Berwick, also a Third Rate (launched in 1679), had a battery weighing 129 tons, virtually identical to that of the smaller Second Rates, and could deliver over 580 pounds weight of shot. Ships also had to carry large amounts of powder to sustain these armaments. The Britannia carried 400 barrels, the Berwick 310, the Monck 270 and the Centurion 130.7 The compulsion to cram in as many heavy guns as possible meant that ships often sat uncomfortably low in the water. At her launching in 1664, the lowest gunports of the Second Rate Royal Katherine were only some three feet above the waterline, and that was before any guns or provisions were loaded into her.8 Although this was extreme, master shipwrights, captains and naval administrators were all perfectly happy with rather less than four feet of freeboard on a fully laden ship; in 1672, the midships gunports of the fleet flagship Prince were only 3ft 5in above the waterline.9 This meant that the largest ships could not open the gunports of their main battery in anything other than almost calm conditions, but that was considered acceptable in ships that were meant to operate exclusively in home waters in summer, especially when the reward was an additional 25 per cent weight of ordnance.10 Nevertheless, it sometimes worked to the disadvantage of the British in action, notably at the Four Days’ Battle of 1666, when choppy seas on the first day meant that the lower tier gunports on the larger ships could not be opened on the lee side, so their heaviest armament was rendered useless.

DECK ARRANGEMENT

Ships were often referred to by their number of complete gundecks. The largest ships in the fleet (those which mounted between about sixty and a hundred guns) had three gundecks, medium-sized ships had two, and the smallest warships just one. However, these were not the only decks contained in the hull. Above the ‘floor’ of the ship, which contained ballast, was the hold, containing some storerooms for water and provisions. At first, this contained a number of false beams which did not support a deck, but from about the third quarter of the century onwards these beams were planked over and came to be called the orlop deck, which contained more storerooms, some cabins, the surgeon’s cockpit and the cable tiers.11 The main powder magazine was under the gunner’s storeroom in the bows, with a smaller one beneath the after end of the orlop. The next deck was the gundeck, above which was the upper deck in a two-decker; a three-decker had a middle deck as well. Several structures were built upon the upper deck. Most ships had a forecastle, containing the cook’s hearth, while a lengthy quarterdeck, the preserve of the ship’s officers, ran to the stern from abaft the mainmast; both of these were armed. Larger ships also had a poop deck astern of the quarterdeck, which was usually only lightly armed. The uncovered area between the forecastle and the quarterdeck was known as the waist.

LENGTH

Ship lists of the period, such as the register of ships in service from 1660 to 1686 that Pepys maintained, usually specified the length of the keel, which was used to derive the tonnage, rather than the length of the gundeck, which became the most common (and perhaps still the most familiar) measurement in the eighteenth century.12 However, the length of the gundeck is recorded for some ships built prior to 1660, and for all the large and most of the small ships built after 1670.13 After the mid-1670s shipwrights increased the length of the keel in relation to the gundeck length, which distorted the tonnage measurement. Charles II sought to allow for this in 1677 by introducing a new formula for calculating the length of the keel.14 In practice, the maximum length was restricted by the need to avoid ‘hogging’, the sagging at the ends which could take place if a ship was too long for the number of guns it was carrying, particularly in the narrower bow and stern. First Rates, carrying about eighty-six to a hundred guns, had main gundecks that were up to 167 feet long. Smaller three-deckers, Second Rates of about sixty to ninety guns, had gundeck lengths varying from about 135 feet in the oldest ships up to almost 163 feet in the Neptune of 1683. Third Rates, the largest two-deckers (carrying fifty-eight to seventy-four guns), had gundeck lengths ranging from about 130 feet in older ships up to more than 150 feet in later vessels. Fourth Rates, carrying thirty-four to sixty guns, were between 110 and 138 feet long on the gundeck; Fifth Rates, the smallest two-deckers, were of about ninety to 110 feet, while single-decked Sixth Rates varied hugely.15 The gundeck-to-beam ratio of ships of all sizes was of the order of 3.7:1.

THE SHAPE OF THE HULL

As well as being larger than the ships of their usual enemy, the Dutch, English warships also had a different shape. The upper part of the sternpost was connected to the ship’s frames by curved transom timbers, which produced a rounded appearance at the stern, the ‘round tuck’, which was unique to English ships; the Dutch and most other continental warships had right angles instead. Dutch ships were built with the shoal waters of their coast in mind: hence they had shallow, nearly rectangular midships sections with broad, flat bottoms, which meant that they tended to be more stable gun platforms in calm waters than the more U-shaped English ships, which were much deeper.16 These differences resulted in comparable underwater volumes for a given length and breadth. The problem with the English pattern, and the shipwrights’ obsession with fine (or narrow) lines, was that it sometimes reduced displacement, the underwater volume essential to a ship’s stability.17 The constant pressure to squeeze in as many guns as possible also contributed to serious stability problems. Although no English warship suffered the same fate as the Swedish Vasa, which overturned on its maiden voyage in 1628, some easily could have done, most notably the Royal Katherine of 1664. Several of the great ships had to be girdled relatively soon after being built; in other words, the beam was artificially increased by adding extra planking at the waterline, which naturally reduced the ship’s speed. Fortunately, this was almost always successful.

SPEED AND MANOEUVRABILITY

The fastest ships could make at least ten knots, but many factors, notably wind, tide and the cleanliness of the hull, could reduce this, and six to eight knots would have been more usual; the Assistance made seven in a fresh north-easterly in the Bay of Biscay in 1675, the Monmouth ten in similar wind conditions in the same waters in 1668.18 The steering system, which depended on the whipstaff, and the square rig both contributed to the cumbersomeness of some of the larger ships in particular (although the best and beamiest of the big ships were often quite fast, as they could bear more sail). Ships were hard to manoeuvre if the wind was dead astern, and sailed best if the wind was on the quarter or abeam; headings were limited to between half and two-thirds of the compass, as ships could not sail closer than six points to the wind. British ships of this period did not roll badly, but their fine ends made them prone to pitching, and thanks to the competing demands of heavy armaments, fine lines, heavy timbering and large sail areas, they unavoidably heeled significantly to leeward.19

THE RATING SYSTEM

The division of ships into six rates, based on the number of guns that they carried, dated originally from the reign of James I, and subsequently became the basis for determining different rates of pay for officers.20 Although the armament, and thus the overall size, of the ships of each rate increased substantially from the 1650s to the 1670s, contemporaries continued to know perfectly well what was meant by the terms ‘Second Rate’ and ‘Third Rate’, though these were sometimes used interchangeably with other ways of describing ships, and many official lists of the period classify ships by rate. There was some overlap between the rates, and this led to confusion. In 1662 Pepys discovered that no-one, except possibly the king and the Lord High Admiral, actually knew whether the Royal James was a First or a Second Rate. Her officers and crew naturally contended that she was a First, and thus entitled to higher pay.21 There was similar confusion over the Fourth Rate Leopard, which was almost as large and powerful as the smaller Thirds.22 Pepys attempted to impose a more logical order in 1677, although the complex implications of rerating ‘borderline’ ships (especially the outcry that would occur if their officers’ wages were reduced) ultimately defeated him.23 It was not uncommon for a ship to be re-rated several times in its career. The St Michael of 1669 was built as a Second Rate, but was soon reclassified as a First; the Second Rate Old James, dating from 1634, was re-rated as a Third in 1677; and several Fifth Rates were rapidly upgraded to Fourths. All of these considerations meant that, by the late 1670s and 1680s, it was common to refer unofficially to subcategories of some of the larger rates; these were usually ‘small’ and ‘large’ Second, Third or Fourth rates, distinctions which were often synonymous with ‘old’ and ‘new’ (see table).

NUMERICAL RANGE OF ARMAMENT OF EACH RATE

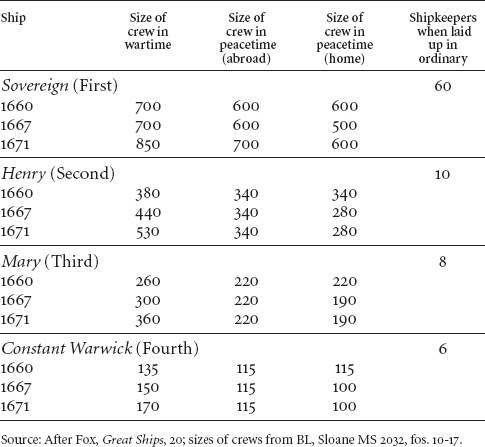

Establishments laid down the numbers of men to be borne on each ship. The size of the crew was determined chiefly by the number of guns the ship carried, and this was made explicit in the ordnance establishment laid down in 1677.24 However, both crew sizes and the number of guns carried also varied according to circumstances, with larger crews required in war than in peace, and overseas than in home waters. The increase in the number of guns carried by warships in the Restoration naturally led to an increase in the sizes of crews, and thus to the cost of sending a warship to sea (see table).

COMPLEMENTS OF SHIPS OF DIFFERENT RATES

TRENDS IN SHIP DESIGN

There were a number of co-ordinated shipbuilding programmes. Eight ships were ordered together in 1664, although the two largest were so expensive, and would take up so much time and resources during wartime that one had to be cancelled and the other deferred for so long that it merged with the next programme. This was an ambitious order of ten large ships, ordered in 1666, but only eight had been completed by 1671, and it is not certain that all of these belonged to the same programme.25 The largest programme, the ‘thirty new ships’ commenced in 1677, was completed in toto. However, these programmes did not produce standardised ‘classes’ of warships, as each shipwright had considerable leeway in fulfilling the specification. The thirty ships were built to a standardised list of principal dimensions and scantlings, but in practice they all varied slightly in length, breadth or appearance. Over time, several important changes to the appearance of ships took place. The most apparent of these affected the shape of the bow. The long, low and extravagant beakhead that had been fitted to the Sovereign of the Seas when she was first built in 1637 was replaced by a shorter structure in 1652.26 Under water, beginning in 1677 the fashion shifted even more in favour of longer keels with decreasing rakes, partly because King Charles II personally favoured the Dutch-style ‘upright stem’, which made an angle with the keel, rather than the tangential stem previously employed.27 Forecastles became the norm on all ships of the larger rates, but their inclusion in the design was still by no means automatic; the addition of forecastles to even the Second Rates of the ‘thirty new ships’ programme was agreed by Charles II and the Admiralty only after a debate, some months after building work had commenced.28 Stern galleries began to appear on British warships from the early 1670s onwards, being fitted first to the Royal Charles, built at Portsmouth in 1673. Individual shipbuilders were always able to work their own preferences into their designs, and fashions changed constantly. Sailing qualities could be altered radically by seemingly minor adjustments to the positioning or rake of the masts; in 1689 the foremast of the Anne was moved some sixteen inches further aft to correct a tendency for her to fall off in a head sea because the foresail was too far forward.29

The Third Rate Grafton, launched at Woolwich in 1677, became closely associated with her namesake Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Grafton, who flew his flag in her on several occasions. She was captured by the French in 1707.

(US NAVAL ACADEMY)

This superb model of the Second Rate Coronation of 1685 gives the ship a posthumous fame out of all proportion to her short, inglorious career; she was wrecked at Penlee Point near Plymouth in 1691.

(KRIEGSTEIN COLLECTION)

Both the changing fashions in the design of ships’ sterns and the often remarkable degree of detail in ship models of the period are illustrated by these views of the sterns of the Grafton (1679) above, and the Royal William (1719) left; the latter has the stern galleries that began to appear in large British warships from the 1670s onwards, and became prevalent during the first half of the eighteenth century.

(BOTH PICTURES - US NAVAL ACADEMY)

SHIP MODELS

The Restoration was the first great age of the so-called Navy Board ship model. Several superb examples survive at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich; in the Science Museum, London; in other institutions both in Britain and overseas; and in some private collections.30 There is evidence for the existence of ship models much earlier in the seventeenth century (Phineas Pett made one in 1608 as part of his proposal to the king for the building of the Prince Royal),31 and many seem to have been extant by the end of the Interregnum. After taking up his post at the Navy Board, Pepys soon started to assemble his own collection, though sadly this was dispersed after his death.32 Unlike eighteenth-century models, the models of this period seem to have closely reflected contemporary shipbuilding practice.33 The majority were clearly not made as preliminary designs, as was once assumed; some may have been commissions, while others were probably working models built simultaneously with the ship itself, to illustrate salient points of her layout and construction.34 The earliest model that can be definitively identified with a specific ship is that of the St Michael of 1669, a remarkably intact and detailed survival which was owned by one of her commanders, Sir Robert Holmes.35