Fourth to Sixth Rates

AT FIRST, the term ‘frigate’ strictly referred to a method of construction rather than to a specific size of ship: long, fine lines, with comparatively light scantlings (breadth and thickness of timbers) and an emphasis on speed rather than weight of gunnery. In practice, the term was sometimes applied loosely to almost any ship, much as in the twenty-first century many in the media refer to almost any warship as a ‘battleship’. In 1655 one commentator advocated a blockade of Spain by‘eighty sail of frigates’, in other words the great majority of the navy’s serviceable ships of all shapes and sizes, and in 1673 a member of the ship’s company of the lumbering old Second Rate St George described her as a ‘frigate’ (though admittedly, he was a soldier).1 Even the vast Sovereign of the Seas was sometimes called a ‘frigate’, and the term was certainly used to describe new Third Rates like the Speaker/Mary of 1651, which were known for a time as ‘great frigates’. After the Restoration, though, the definition of the word became more explicitly functional, and gradually came to be applied most commonly to Fifth and Sixth rates alone, though Fourths were sometimes referred to in the same way. The term ‘frigate’ was still used frequently when referring to larger ships, but some of these were so heavily built and armed that the original meaning was largely obscured (even as late as 1692, the contracts for a group of 80-gun ships described them as ‘frigates’).2

Regardless of the semantics, the concept of the small fast frigate, at least as far as English thinking was concerned, evolved gradually between the 1620s and the 1640s. With its emphasis on speed and offence, rather than bulk and defence, the flush-decked frigate represented a revolutionary departure in English ship design. Both the word and the design concept were drawn from the privateers of Dunkirk, which became a particularly active threat to English shipping before and during the civil wars.3 Even until the early 1640s, though, small warships built specifically to pursue the Dunkirkers tended to be heavily framed and overburdened with elaborate decoration.4 The political changes and upheavals in naval administration that accompanied the civil war led to a significant change in design philosophy. Two captured Dunkirkers became the model for the Constant Warwick, built in 1645 as a privateer for her namesake the Earl of Warwick, the Lord High Admiral. The new ship was quickly taken into naval service, and proved so successful that seven more were built in 1646–7. Despite being poor seaboats, which had to be modified in the 1650s by the addition of forecastles, most of them had long and highly successful naval careers.5 The Constant Warwick herself survived until her capture by the French in 1691.

The Stirling Castle, one of the elegant Third Rates built as part of the Thirty Ships programme, as drawn by Willem Van de Velde the Younger. Launched at Deptford in 1679, she was lost on the Goodwin Sands during the Great Storm of 1703; many artefacts have been recovered from the wreck.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, GREENWICH)

The decline in the number of the Fourth to Sixth rates, relative to the bigger ships, caused serious difficulties when war broke out against France in 1689. During actual or putative conflicts with France in 1666 and 1678, it was pointed out that smaller ships would be of more use in a French than a Dutch war, because the French posed more of a threat to both the coastal trade and oceanic trades passing through the Channel, Irish Sea and Western Approaches.6 In 1679 a new Admiralty Commission, opposed to the policies of both Pepys and King Charles II and more overtly committed to the defence of trade, investigated the possibility of building new Fourths to Sixths. The scheme was dropped, presumably because the huge construction programme of bigger ships, to which they had been committed by their predecessors, swallowed all the funds.7 Consequently, the value of the small rates had to be quickly re-learned by William III’s and Queen Anne’s naval administrators. The lack of suitable convoy escorts led to protests from merchants in the early years of the war of 1689–97, leading to the increasing deployment of Third Rates on such duties and to the passing of a ‘Convoys and Cruisers Act’ in 1694. Fifty-eight Fourths, fifty Fifths and twenty-six Sixths were built between 1689 and 1705, along with eighty-eight ships of the First to Third rates, thus reversing the emphasis of their predecessors’ reigns.8

A fine model of a Fourth Rate of the mid-1650s.

(US NAVAL ACADEMY)

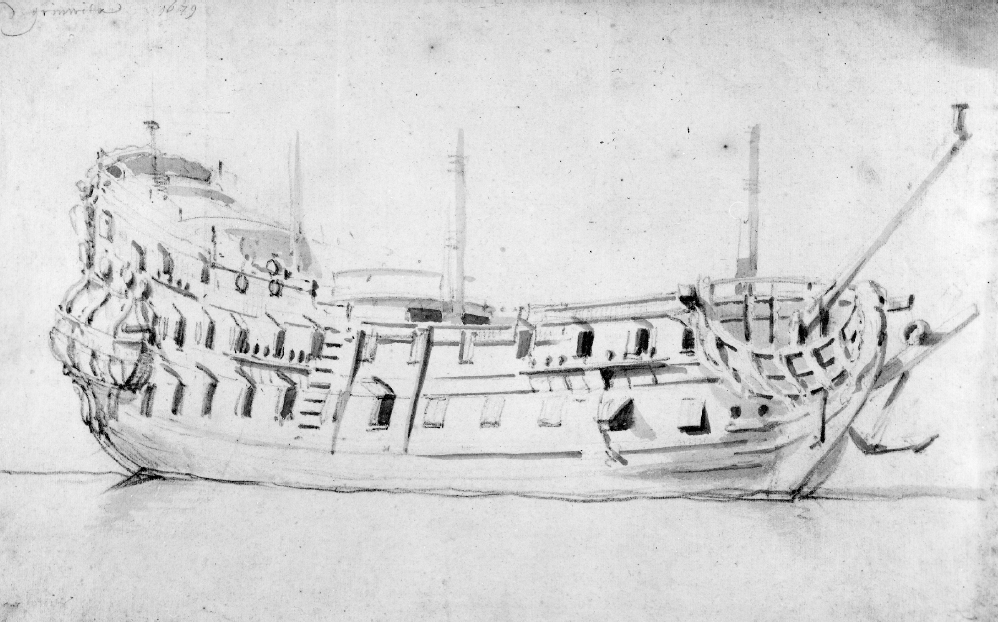

The Greenwich, a Fourth Rate built at Woolwich in 1666; one of the few new ships to be completed during the second Anglo-Dutch war.

(WILLEM VAN DE VELDE THE YOUNGER; US NAVAL ACADEMY)

FOURTH RATES

The Fourth Rate ship constituted the backbone of the peacetime navy. The largest could carry fifty-four to fifty-eight guns, but most carried between forty-six and fifty. The first batch of eight, built during the civil war, had been designed for only thirty-two to thirty-four, but these were much heavier than the weapons carried in later years, so there was no appreciable increase in the overall weight of armament.9 Apart from size, this was the crucial difference between the Third and Fourth rates from the 1660s onwards; although they often carried similar numbers of guns (and the Leopard even carried as many as one old Second Rate), the Fourths invariably carried much lighter weapons. Twenty-six Fourths were built between 1650 and 1654, with all but one surviving the Restoration, but only another twelve were built between 1659 and 1688, two of which were experimental ‘galley frigates’. This was due partly to the Stuart brothers’ preference for larger ships, and partly because of a shortage of money; six Fourths were ordered in 1670, but were soon cancelled. Above all, though, the Commonwealth’s Fourth Rates proved astonishingly durable, and needed no replacement. The Ruby survived thirteen major actions, more than all but one other warship in the history of the navy, and she was still going strong in 1707 at the age of fifty-six, when she was finally taken by the French. The great majority of her contemporaries also survived well into the 1690s, despite being on active service for a far higher proportion of their lives than any of the larger rates. The Adventure of 1646 was considered such a successful design that forty years later, one authority was still proposing to base the dimensions of new Fourth Rate on her; the Navy Board demurred and suggested larger ships, though they had to be particularly tactful as the ‘authority in question was King James I and VII.10 As well as being considered suitable for the line of battle, Fourth Rates were regularly employed on ‘convoy and cruiser’ work in both war and peace. They were ideal for detached operations in the Mediterranean or the Caribbean, either individually or in small squadrons. The largest could even be used as flagships: the St David and Bristol served as such in the Mediterranean in 1669–70 and 1680–2 respectively.

THE ‘GALLEY FRIGATES’

The use of oars in English warships had a long history. In their early years, the new frigates of the 1640s were fitted for sweeps, and in 1675 Fifth Rates allocated for Mediterranean service were ordered to be fitted with oars.11 In the early 1670s, though, several other factors led to the construction of a new class of warship, the ‘galley frigate’. The depredations of the Barbary corsairs, whose ships were often fitted with oars, led to several attempts to fight like with like, beginning with the commissioning of an out-and-out galley, the Margaret * She soon proved to be an expensive mistake, but in 1675 or 1676, according to Pepys, Captain Thomas Willshaw, a former naval captain who had been trading in the Mediterranean, reported to the king that the French were building galley frigates at Toulon. Willshaw might have been referring to La Bien-Aimée, of twenty-four guns, built at Toulon in 1672, although at least one contemporary report suggests that the French ship in question had not been completed by 1676. Charles, James and Prince Rupert quizzed Paolo Sarotti, the Venetian ambassador, for information on his country’s practice with such craft.12 At the king’s personal instigation, two galley frigates were constructed shortly afterwards, the Charles Galley by Phineas Pett at Woolwich (out of timbers that were already lying in the yard) and the James Galley at Blackwall by Sir Anthony Deane’s son.13 Although they were classed as Fourth Rates, they were allocated only thirty-two and thirty guns respectively by the ordnance establishment of 1677, as much of their lower gundeck had to be set aside for the sweeps of the oars.14 A third galley frigate, the Mary, was subsequently built by contract at Cuckold’s Point, Rotherhithe, in 1687,‘to the same form as the James Galley’.15

Opinions on the first two galley frigates were initially mixed. Pepys’s friend Henry Shere, engineer of the Tangier mole, watched them arrive at the colony in February 1677 and was impressed at first, but he soon came to the conclusion that they were undermasted, their oars were too slight, and their guns were badly distributed.16 He raised the last point with the king and the Admiralty Commission, who agreed that the absence of guns between decks was a significant shortcoming of their design.17 Manning them was also problematic, as Watermen’s Hall was hard pressed to find sufficient rowers.18 Even with a full crew, the ships were not as fast under oars as had been hoped; during a trial off Start Point in 1688, with three men to each of her forty-two oars, the Charles Galley managed only a paltry three knots (although her crew celebrated, considering this to be an impressive performance).19 Nevertheless, the two ships soon proved their worth. They were narrower, finer and faster than other Fourth Rates, and were employed extensively against the Barbary corsairs and Sallee rovers during the late 1670s and 1680s. The James Galley was wrecked on Longsand Head in November 1694, but the Charles and Mary survived and were ultimately rebuilt. With their fine lines, emphasis on speed, and main armament placed on the upper deck, the galley frigates have been rightly described as the lineal ancestors of the frigates of Nelson’s day.20

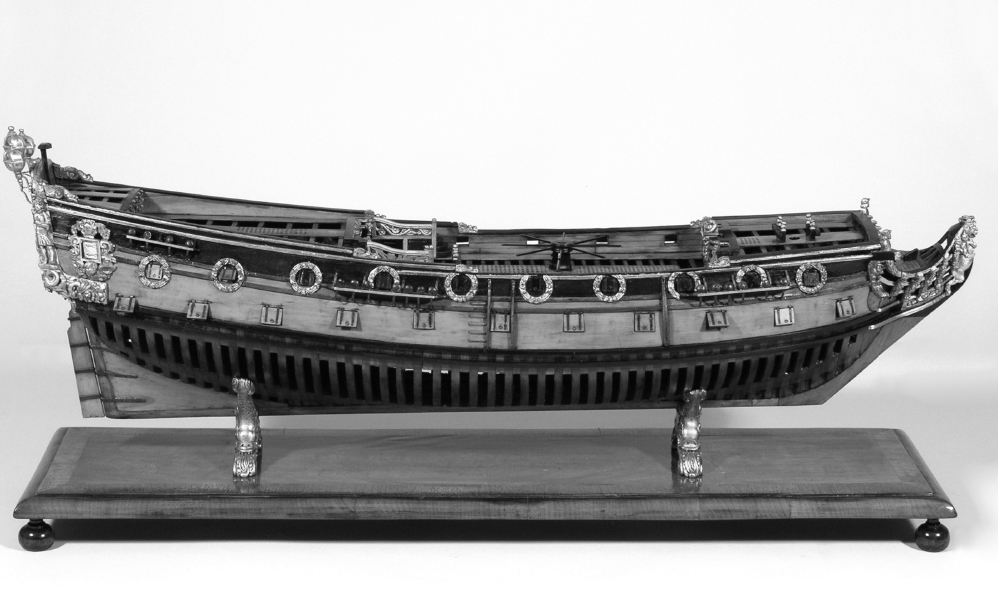

A contemporary model of the classic Fourth Rate frigate Adventure, built at Woolwich in 1646, and which served for over forty years.

(KRIEGSTEIN COLLECTION)

A drawing of the Charles Galley by Willem Van de Velde the Younger, clearly showing the ports for the oars.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, GREENWICH)

THE KINGFISHER AND THE MORDAUNT

The 46-gun Fourth Rate Kingfisher, built by Phineas Pett at Woodbridge in 1675, was another unusual response to the problems posed by the Barbary corsairs. In many ways she was a precursor of the ‘Q-ships’ employed against U-boats during World War I: designed to resemble a merchantman, her upper deck guns were concealed behind false bulwarks, and she also had a false figurehead which could be removed rapidly.21 In 1681 she was attacked by seven Algerine corsairs, and despite the death of her captain, Morgan Kempthorne, she successfully fought them off.* The Kingfisher was later deployed in home waters as a conventional Fourth Rate, and survived until her ‘rebuilding’ in 1699 (her new incarnation survived as a hulk at Sheerness until 1728).

The 48-gun Mordaunt was built at the private Castle yard at Deptford in 1681 as a privateer for a syndicate headed by Charles, Viscount Mordaunt of Avalon (later, as Earl of Peterborough, the ‘generalissimo’ of allied forces in Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession). At the time, Mordaunt was a strong supporter of the ‘whigs’ and of the exclusion of the Duke of York from the succession, and it is unclear what he planned to do with the ship. It was rumoured that he intended to sail her under the flag of the Elector of Brandenburg for unspecified operations in the Mediterranean. Fearing the ship might be used to attack Spanish shipping, the Spanish ambassador complained to Charles II, who ordered it stopped for more than six weeks. By the end of August Mordaunt was back in favour, and in November 1681 the king dined on board with him. Mordaunt eventually defaulted on the crew’s wages, and in 1683 the navy purchased the ship from him.22 She undertook an unusual deployment to West Africa in 1684–5, where disease decimated a large part of the crew. She was eventually wrecked on the coast of Cuba in 1693.

FIFTH AND SIXTH RATES

Seventeen Fifth Rates were built in the 1650s, but only another nine thereafter. Three of these were built almost by accident during the second Anglo-Dutch war; one was built from the timbers assembled for a Second Rate that was subsequently cancelled, while another was built from the waste timber left over from the reconstruction of the Victory, and was wittily named the Little Victory by Charles II.23 The Nonsuch of 1668, which was soon re-rated as a Fourth, was built according to the theories of the renegade Dutch captain Laurens van Heemskerck, who believed that building a ship with the grain of all her timbers running the same way would lead to an increase in speed of up to a third. In fact, there was no discernible difference between the performance of the Nonsuch and that of her conventional contemporaries, and Pepys was scathing about the whole matter.24 The largest Fifth Rates could carry up to forty-two guns, but most carried between twenty-eight and thirty-two. In wartime, they served as scouts for the main fleet, and were sometimes deployed to windward of the line of battle to act as an additional line of defence for flagships, particularly against fireship attacks (a task which her crews found understandably unpalatable).25 They were also expected to escort their own fleet’s fireships into action, and rescue their men.26 Their more usual role in both peace and war was very similar to that of the Fourth Rates, namely ‘convoy and cruiser’ duty, particularly in home waters. The same was true of the very few Sixth Rates, a class that became increasingly unfashionable during the period. Of the fourteen Sixths that served after 1660, only five made it past 1688. One of these was the Saudadoes, originally built as a private yacht for Charles II’s much put-upon wife, Catherine of Braganza (who nominated her captain), and which was eventually captured by the French in 1696. Conversely, the Fifth Rates proved almost as durable as the Fourths. Several were converted into fireships or reclassified as Fourth Rates, but the Pearl of 1651 survived until 1697, when she was sunk as a foundation at Sheerness.

PRIZES

Apart from the Second Rate French Ruby, captured in 1666, and several Dutch Thirds (mostly East Indiamen captured in 1665), most of the prize ships taken and then brought into British naval service were Fourth to Sixth rates, or unrated vessels. Five had been Royalist ships during 1648–51: of these, the Fourth Rate Marmaduke was one of the blockships sunk in the Medway in 1667, while the Sixth Rate Truelove became a fireship and was expended at the battle of the Texel on 11 August 1673. Several prizes were taken from the Barbary corsairs, and some of these were subsequently employed as cruisers or guardships.* The great majority of prizes were Dutch, and several of them served under the British flag, although in most cases their careers were not particularly long. On the whole, the Commonwealth regimes retained their prizes for longer, and employed them more extensively, than did the restored monarchy, although in 1665 Sir William Coventry hoped that including prize ships in the fleet, and concealing their true colours, would confuse the Dutch.27 This seems unlikely, as the British tended to cram in much heavier guns than the Dutch ships had originally been designed for, with an inevitably detrimental effect on the light scantlings that the Dutch favoured (and they would have been much lower in the water, a sure giveaway of their new credentials).28 Many of the prize warships were lost in action or retaken, and others were sold out of the service soon after each Anglo-Dutch war ended. The Matthias, Charles V and Sancta Maria were burned in the Medway by their former owners in 1667. Many of the Fifths and Sixths were converted into fireships and expended in action. The brief career of the Fifth Rate Orange was fairly typical for a prize ship in the 1660s. Originally the Dutch Oranjeboom, of thirty-two guns, she was captured in 1665 and in the following year was employed on cruising duties in the English Channel, before moving in the autumn to convoy colliers on the east coast of England.29 She later went out to the Mediterranean as part of the fleet deployed in the war against Algiers, but foundered in the Gulf of Lyons in September 1671.

A model of an unidentified Fifth Rate of c.1670

(KRIEGSTEIN COLLECTION)

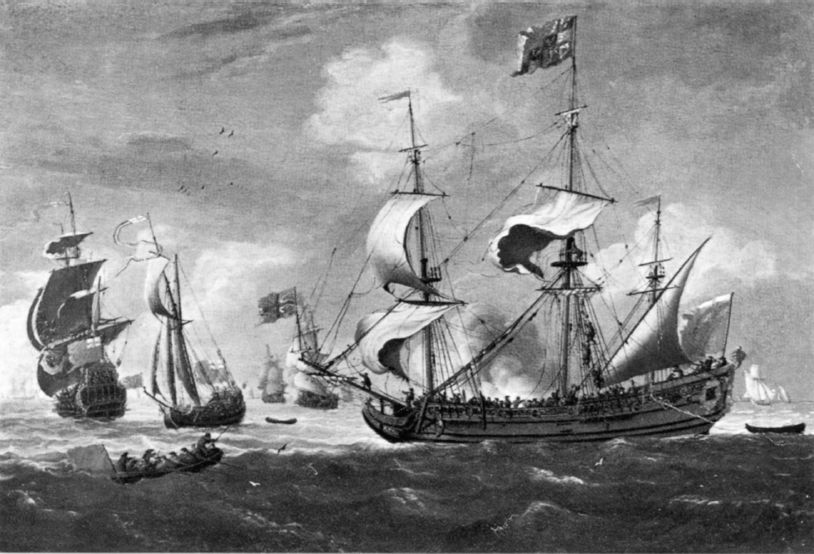

Catherine of Braganza’s ‘private warship’, the Saudadoes, flying the Queen’s standard at the main.

(PRIVATE COLLECTION)

HIRED WARSHIPS

The Rump Parliament hired large numbers of merchantmen at the beginning of the first Anglo-Dutch war. These were more lightly built than purpose-built warships, and generally carried smaller guns. At first many of their original masters, who were also often part-owners, were retained in command, but their unwillingness to hazard their own property almost caused an outright catastrophe at the battle of Dungeness (December 1652); half of Blake’s fleet consisted of merchantmen, and many of the captains failed utterly to come to their admiral’s assistance. Subsequently, new regulations prevented the existing masters retaining their commands, ships mounting fewer than twenty-eight guns were discarded, and it was decreed that hired ships should not form more than one-fifth of any fleet (this was soon flouted; twenty-nine of the 101 British ships at the Gabbard were hired).30 To be fair, the traditional contracts imposed on the shipowners hardly gave them any incentive to hazard their ships, for they were meant to supply guns, ammunition and powder, and to bear the loss if the ship was destroyed or captured. These contracts reflected earlier times and rather less devastating forms of naval warfare, and in 1653 they were replaced by new ones in which the state supplied powder, shot and some of the guns, as well as offering compensation if a ship was lost ‘honourably’.31

The last large-scale hiring of merchant ships for service in the main fleet occurred during the second war. Several were hired in 1664, and twenty other suitable vessels were identified during surveys of the shipping in the Thames during the early months of 1665. Ultimately twenty-four hired merchant ships fought in the battle of Lowestoft on 3 June. All were classed as Fourth Rates, although they were smaller and slower and had thinner scantlings and planking than purpose-built warships of the equivalent rate. The largest were of about 600 tons and mounted up to fifty-six guns, though most mounted between thirty-two and forty-six. Six were retained for the 1666 campaign, when they were joined by eleven more (Dutch prizes more than made good the shortfall). The merchant ships suffered disproportionately heavy damage during the Four Days’ Battle and the subsequent St James’s Day fight, a fact that might have influenced the decision to remove them from the battlefleet during the following war.32 Nevertheless, three were subsequently deployed to the West Indies, and six more were hired at Barbados; eight of these vessels took part in the battle of Nevis in May 1667, ‘the last battle in which the Royal Navy used merchantmen as ships-of-the-line’.33 Following the bad experiences in the first Anglo-Dutch war, hired ships were usually given regular commissioned officers, though the owners retained the right to appoint the boatswain and gunner, and in 1665 owners’ nominees for command were once again accepted.34 After the second war ended, some merchant ships were still hired from time to time to undertake escort duties or to respond to emergencies, such as ‘Monmouth’s rebellion’ of 1685. A significant number were hired in the early years of the French war that began in 1689 to make good the deficiency in ‘convoys and cruisers’, but it was clear that they no longer had any place in the main fleet.

* See Part Two, Chapter 8, pp62-3.

* See Part Twelve, Chapter 49, p253.

* See Part Ten, Chapter 34, p216.