Unrated Ships and Vessels

SLOOPS AND KETCHES

USUALLY TWO-MASTED AND SQUARE-RIGGED, a total of twenty-two sloops served between 1660 and 1688. Most carried four guns, although some had only two; most had a peacetime complement of ten, though some carried up to twice or three times that number in wartime. The largest were over fifty-five feet long in the keel. Although they were excellent, nimble craft, they had a singularly disastrous service record: five were wrecked, three were lost in action, and one was ‘run ashore by slaves to be sent to Cadiz, in Tangier Bay’.1 However, some of the survivors had reasonably lengthy and respectable careers. The Bonetta of 1673, which was extensively deployed in the Mediterranean and the West Indies, was the only one to survive the ‘Glorious Revolution’, but two lasted until 1686 and eight until 1683, when something of a concerted cull of the navy’s smallest vessels took place.2

Between 1660 and 1688 Pepys recorded a total of fourteen two-masted ketches (generally square-rigged on the mainmast) in naval service. Mounting between four and ten guns, the largest were manned by fifty men during wartime, and had a length in the keel of about fifty feet.3 They were sometimes employed on foreign stations, or as convoys in home waters, but their main role in wartime was as advice boats, for which their excellent sailing qualities were ideal. Theywere also useful in defending great ships against fireship attack.4 Consequently, several survived for manyyears. The Deptford and Quaker ketches, dating from 1665 and 1671 respectively, were employed in a variety of roles; the former was once used to transport Charles II’s personal supply of wine from Marseilles before becoming ‘station ship’ at Virginia in 1680s, while from 1677 the latter was stationed at Virginia and then the Leeward Islands.5 Both were still in service after the Revolution. The Deptford was lost in Virginia in August 1689, but the Quaker survived until sold in 1698.6 The Hatton Ketch did not appear in the navy lists of the period, as she had been built for Lord Hatton, the governor of Guernsey, but she was employed as the naval ‘presence’ at the island in the early 1670s and also served as a despatch boat for the main fleet during the 1672 campaign, before reverting to convoying merchant shipping between St Malo and England.7

A small British sloop, possibly Spy (1666) or Emsworth (1667).

(© TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

Jacob Knyff’s painting of a two-decker off Sheerness also shows the heterogenous variety of yachts and other small naval craft that constantly plied the waters of the Thames and Medway.

(PRIVATE COLLECTION)

GALLIOTS, HOYS AND PINKS

Twenty-two galliots and hoys, respectively ketch- and sloop-rigged cargo-carrying vessels, served between 1660 and 1688. Most were taken up from merchants and served only for brief periods in or just after the major wars. They were used chiefly to transport goods to and from the dockyards; thus in 1668 the Black Post Horse Hoy was being used to ship timber from Sherwood Forest to Chatham yard.8 Most were sold soon after the wars ended. One, the Maybolt Galliot, was given to Pepys in October 1667 ‘towards satisfaction for disbursements’.9 However, the Transporter Hoy, used primarily for moving goods back and forth between Chatham and Sheerness, was later rebuilt and remained in service until 1713.10 ‘Horseboats’ were also employed, primarily at Chatham; these were essentially ‘paddlers’, with wheels at the side and the motive force provided quite literally by horse power. Nine square-rigged pinks also served at different times, though this was an older type of vessel, and only two survived until the 1670s. An unexpected addition came in the form of the pink Lyme, which had transported much of the Duke of Monmouth’s abortive expedition in 1685, but she was sold almost immediately after her capture.

SMACKS

Between 1666 and 1673 the navy acquired half a dozen smacks, singlemasted vessels, originally used chiefly for fishing and between twenty-six and thirty-six feet long in the keel. They were generally employed as tenders in and around the Thames and Medway estuaries. The one exception was the Royal Escape, which, as her name implied, was the fishing boat that had carried Charles II to France after his hair-raising flight from the battle of Worcester in 1651. Charles kept her moored opposite Whitehall Palace as a reminder to himself and his subjects. She was kept in service long after the king died, laid up in Deptford yard, and was still in existence in 1714. Nicholas Tattersall, the Brighton fisherman who had skippered her during her famous voyage, benefited spectacularly from the Restoration, being commissioned captain of the 60-gun Third Rate Monck in 1661. Tattersall’s naval career was brief and presumably unsuccessful, for he soon went back to the coastal trade and died in 1674. Nevertheless, his widow was still receiving a pension from the state after the ‘Glorious Revolution’.

FLYBOATS AND DOGGERS

These were primarily Dutch trading vessels (‘flyboat’ was the English corruption of the Dutch word fluyt), flyboats being two- or three-masted square-rigged ships and doggers primarily boats employed in the herring fishery. The twenty-eight of each that served between 1660 and 1688 were all prizes taken in the second and third Anglo-Dutch wars. Like the galliots and hoys, most of them were sold out of the service almost immediately, or given as gifts to individuals (often to the captains who had captured them, providing a useful incentive to officers, even if the state lost financially as a result).11 The few that were retained were employed mostly as tenders, transporting goods to and from the dockyards or the fleet. The Kingfisher Flyboat seems to have been employed by Chatham yard in the 1670s, while the Hardereen also saw a significant amount of service in the late 1660s and early 1670s. Many flyboats were hired during wartime and served as mast carriers and victuallers.

FIRESHIPS

The fireship entered naval mythology following the famous attack on the Spanish Armada in Calais harbour, and it continued to be regarded as a worthwhile weapon for over a century thereafter. In 1666 one commentator in the fleet thought they were so important that ‘as without meat there is no living, so without fireships there is now no naval fighting’.12 The fireship was so feared that it was even the subject of an early arms control proposal, when the Dutch proposed a mutual renunciation of fireships just before the second Dutch war. The Earl of Sandwich was apparently chiefly instrumental in rejecting the proposal, only to die in one of the most potent demonstrations of the fireship’s potential, the destruction of his First Rate flagship Royal James by the Dutch fireship Vrede during the battle of Solebay on 28 May 1672.13 The navy regularly fitted out fireships, a process that involved filling the hull with inflammable material and gunpowder, which were then usually primed with fireballs. They were often small and old warships: eleven purpose-built Fifth Rates were converted for the role between 1672 and 1688, but most of the 111 fireships fitted out between 1660 and 1688 were prize ships or former merchantmen that had been purchased for the task. It was perfectly possible to convert a fireship back into the Fifth or Sixth Rate that she had once been, and several reconversions took place in 1689 when it became clear that it was more urgent to address the shortage of‘convoys and cruisers’. Most of those employed as fireships served for only very short periods, but a few had rather longer service, serving as guardships or being deployed with Mediterranean fleets or as convoys and cruisers.

The Anglo-Dutch wars proved to be something of a heyday for the fireship, despite the facts that they were usually manned by crews of dubious quality (even though substantial ‘danger money’ was available to volunteers), and they proved relatively ineffective against undamaged ships, primarily because of all the imponderables inherent in igniting them at the right moment while simultaneously allowing the crew to make a successful escape.14 Six were expended during the Four Days’ Battle of 1666, fifteen during the desperate defence of the Thames and Medway during the Dutch attack in 1667 and eleven during the last battle of the wars, off the Texel on 11 August 1673.15 The British had no stunning success to match the Dutch destruction of the Royal James until 1692, when twenty-four fireships were deployed against the French fleet at Barfleur and La Hogue. Ten were expended, mostly to no avail, but one of them, the appropriately named Blaze, fastened herself to the Comte de Tourville’s fleet flagship, the magnificent 104-gun Soleil Royal, and destroyed her (though to be fair, the French ship had already effectively been abandoned under the walls of Cherbourg).

The smack Royal Escape.

(© TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

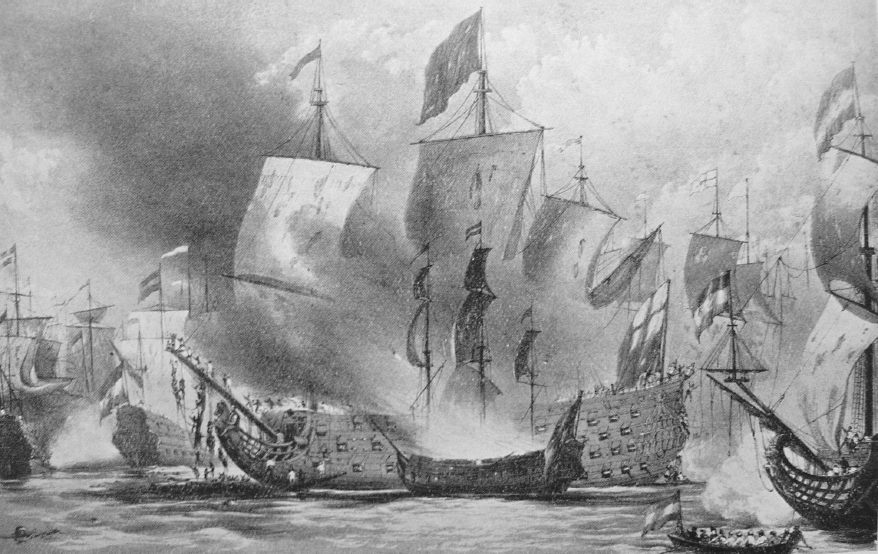

The destruction of the Royal James at the Battle of Solebay, 28 May 1672. The original painting is shown on page 230-1

(ANONYMOUS ENGRAVING, AFTER VAN DE VELDE)

BOMBS

The bomb vessel was a French invention, developed originally in 1682 for an attack on Algiers.16 The design was copied by the British, who introduced it into their own navy in 1687 when the Salamander was built at Chatham, followed by the converted yacht Portsmouth and the much larger Firedrake at Deptford in the following year. Bombs carried one large mortar on each side, placed on reinforced beds in the converted hold space in the waist of the ship. The British soon added a significant improvement over the original French design by incorporating a traversing turntable, rather than having the mortars fixed to fire forward.17 Another seventeen bomb vessels were built during the 1690s, when they were used primarily for a series of vicious but ultimately ineffective attacks on French coastal towns, attracting much criticism (even in Britain) as an underhand and unchristian means of waging war on innocent civilians.18

The attack on Dieppe by bomb vessels and other men-of-war, 12 July 1694.

HOSPITAL SHIPS

The concept of a hospital ship was already well established in the seventeenth century. None were deployed during the first Anglo-Dutch war, but one was sent with the ill-fated expedition to Hispaniola and Jamaica in 1655.19 More provision was made during the second war, thanks primarily to campaigning by James Pearse, newly appointed as Surgeon-General of the fleet. The Loyal Katherine served with the fleet at the battle of Lowestoft on 3 June 1665. In the aftermath of the battle, she handled some five hundred British and Dutch casualties, and her relatively small store of medical provisions was overwhelmed.20 A second ship, the Joseph, was hired in the same year, but was replaced by the Maryland Merchant for the 1666 campaign. Even so, the proximity of the Dutch war engagements to the shore, and the difficulty of fitting out a hospital ship with sufficient equipment, meant that most casualties were ferried ashore in small craft as quickly as possible after a battle. Two hired merchantmen, the John’s Advice of 330 tons and the Catherine of 260, were employed as hospital ships during the third Anglo-Dutch war, but they proved to have unsatisfactory accommodation for both the surgeons and their patients. The Helderenberg, a Dutch ship given to the Duke of Monmouth in 1685 for his invasion of England, was made into a hospital ship in October 1688, but her service was shortlived, as she was run down and sunk by the Bonadventure off the Isle of Wight in December.21 Provision of hospital ships improved significantly when the Anglo-French war began in 1689; within two years, there were four hospital ships in service, two for each of the Red and Blue squadrons.22

A draught of a bomb vessel, believed to be the Salamander of 1687, apparently copied from a lost original.

(FROM JOHN CHARNOCK’S HISTORY OF MARINE ARCHITECTURE, 1800)

HULKS

Hulks were used for a variety of purposes. In home waters, hulks were employed in the dockyards as accommodation ships, or for storage. Careening hulks were used to pull active ships over onto their sides so that their bottoms could be cleaned, while mast hulks were employed as an essential part of the process of fitting masts to ships in service. In outlying harbours or overseas, hulks effectively acted as naval bases in miniature, in harbours with few or no facilities for British warships. The Elias was used in this way at Plymouth in the 1650s, the Europa at Malta in 1675–6, and the Leopard at Gibraltar in the 1680s. Hulks were generally old vessels that had reached the end of their active lives and were then cut down to their gundeck ports; they could be as large as the former Second Rate St George. Others were Dutch or Spanish prizes. Several ended their days by being sunk as foundations for new developments in the dockyards, particularly at Sheerness.

THE MEDITERRANEAN GALLEYS

Designed by Beneditto Carlini and launched at the Medici arsenal in Pisa in 1671, the Margaret Galley was 153 feet long on the gundeck, about as long as a contemporary Second Rate, and may have been intended to be the first of up to six such vessels.23 Named after the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, the Margaret was intended to operate from Tangier, but was never successful. The manning of the galley, which required a crew of 460, was a serious problem for a nation with no tradition of operating such craft. Several dozen slaves for her crew were recruited from the Maltese slave market;24 the ship’s company also included Italian mercenary soldiers and thirty Native Americans, brought over from New England for the purpose.25 She had a French captain who had allegedly once served in Louis XIV’s galleys and was related to a knight of Malta; her lieutenant was Italian, while her surgeon was French. The Margaret, which cost some £18,000 a year to run (50 per cent more than the total cost of operating a First Rate for half that time), seems to have made just one major voyage, from Leghorn to Tangier, and was taken out of service early in 1676, to be replaced by the cheaper and more efficient ‘galley frigates.’.26 She was laid up at the west end of the Tangier mole, and in 1677 she was given as a gift to Colonel George Legge, master of the Ordnance, and his friend Sir Roger Strickland, who in turn nominally handed her back to Tuscany.27 The hull of a second galley, ordered from Genoa at the same time as the Margaret, was completed but then not fitted out, primarily because war broke out between Genoa and Savoy, although another factor was the Franco-Spanish war of the 1670s, which exhausted the western Mediterranean slave markets and made it impossible to man her.28

YACHTS

The ‘royal yacht’ entered the navy in 1660 when the Mary was given to Charles II as part of a spectacular ‘Dutch gift’ of artworks and other goods that marked his restoration. The king had developed a love of sailing in 1646, when he was briefly in exile on Jersey, and the Mary was soon followed by a series of English-built copies, beginning with the Anne, launched at Woolwich in 1661. In all, twenty-five yachts were built during the king’s reign. The largest was over sixty-six feet long, over twice the length of the smallest, and bigger than most Sixth Rates. Charles’s choice of names was idiosyncratic and not a little playful: the Cleveland, Portsmouth and Fubbs were all named after his mistresses (in the case of the last, after the physical characteristics of one of them), the Monmouth after his eldest illegitimate son, and these vessels were usually reserved for the use of their namesakes. The Isabella Yacht was virtually the private toy of another of the king’s offspring, the Duke of Grafton, who nominated all her officers and took her to the Mediterranean as part of the fleet he commanded there in 1687.29 The yachts proved to be highly successful. Many of them had long lives under several different monarchs, and some survived well into the Hanoverian era. The prototype Mary was not so lucky, for she was wrecked off Anglesey in 1675.30

During peacetime, the yachts provided the king with recreation, and were sometimes used for quite adventurous voyages. In 1661 John Evelyn recorded a race between the king’s yachts, with Charles sometimes taking the helm himself.31 In 1671 a whole fleet of them set off for a summer cruise to Plymouth, much to the chagrin of both the king’s ministers and the authorities in Devon, who were wholly unprepared for a royal visit. Conditions on board the yachts were cramped; Pepys slept on one in 1665 and was kept awake by the snoring of the officers in the adjacent cabins, while over the winter of 1689–90 Admiral Edward Russell spent (in his own inimitable spelling) ‘thre weeks under watter and in a hole in the yautch but a yard long and not two yards broad’.32 In wartime, the yachts were used as despatch boats and tenders to the fleet flagships. Several of the great Van de Velde paintings of the third Anglo-Dutch war show yachts bearing their royal passengers to the fleet. In peacetime, some of the yachts had specific functions, or were employed on general naval duties (although in 1680 Charles II objected to their use as cruisers in the Soundings).33 The Mary was lost while acting as the packet boat between Dublin and Dawpool on the Wirral. In the 1670s the Cleveland Yacht operated essentially as a private cross-Channel ferry for the king’s friends, though she was also used to transport a French aristocrat to Danzig.34 The yachts could also be used for sensitive missions: in 1662 three of them were used to transport Louis XIV’s down payment for the purchase of Dunkirk from Charles II, some £320,000 of bullion.35 But the public and private roles of the yachts soon became blurred. Pepys estimated that between 1679 and 1686 the yachts were used 131 times for the king’s purposes, and 341 times for private occasions; yacht voyages were even being bartered on the Exchange, and both stricter rules for their use and a reduction in their number were proposed, albeit to no avail.36

The very fine lines and elaborate decoration that characterised Restoration royal yachts are clearly apparent in this partially complete model, part of the outstanding collection at the United States Naval Academy.

(US NAVAL ACADEMY)

A Van de Velde drawing of the Cleveland Yacht, built by Sir Anthony Deane at Portsmouth in 1671, and named after Charles II’s mistress.

(© TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)