Armament

THE SUPPLY OF GUNS

ALL NAVAL GUNS were supplied by the Ordnance Office, the same organisation that also provided the army’s artillery trains and the guns in fortifications.* This still had its headquarters in the Tower of London, whence guns could be sent down in hoys to the Thames and Medway yards. Upnor Castle, almost opposite Chatham dockyard, was already being used as a powder store by the 1660s, but it lost its defensive role in the aftermath of the Dutch raid on the Medway in 1667 and was then converted into a dedicated magazine, which by the 1690s stored more powder than the Tower of London.1 Although some brass guns were manufactured at the Tower by the Ordnance Board itself, all iron and most brass guns were made by private contractors. Britain had a particular advantage in brass; its brass-founding technology was the most advanced in Europe, and it consequently employed many more brass guns than its continental rivals.2 The most prominent contractors were the Browne family, successive generations of which held the office of royal gunfounder. They struggled to cope with the unexpected demands caused by the rapid expansion of the navy in the early 1650s and the first Anglo-Dutch war that occurred almost immediately afterwards.3 Nevertheless, they retained their dominant position, and were paid over £136,000 by the government between 1664 and 1678 (although they were owed far more, and because of this eventually went bankrupt in 1682). Their foundries were chiefly in Kent, at Ashburnham, Buckland, Spelmonden and Horsmonden. Other contractors had furnaces at Hawkhurst, Bedgebury, Frant and elsewhere; these were all close to sources of iron ore and to forests that could provide charcoal, which was used before the introduction of coke.4 Powder came from Faversham, Chilworth, the Lea Valley in Essex and mills in Sussex.5

Artillery proving grounds were sited at Snodland, Rye and ‘Mishall’ during the second Anglo-Dutch war; Ordnance Board officers went down regularly to these sites to oversee the test firing of between one and two dozen new guns a day.6 The distances involved may have encouraged a move to Woolwich, which became the usual proving ground in the 1670s.7 Guns and shot were ferried to London and the dockyards by sea from Rye, or along the newly canalised River Wey through Guildford. However, many of the foundries were far from navigable waterways, and guns often had to be taken overland, an expensive and difficult process.8 In emergencies, more guns could be obtained by denuding coastal forts and other garrisons; this was an advantage of the Ordnance Board’s control of both land and sea artillery, and the interchangeable nature of the weapons themselves. The need to strip the forts was particularly urgent in 1666, when in short order the fleet lost three large ships, the Prince, Swiftsure and Resolution, which all carried large numbers of brass guns, and there was no other way of quickly replenishing the fleet’s dangerously diminished stockpiles of its most prized and lethal weapon.9

The landward approach to Upnor Castle, an important ordnance store throughout the period; its batteries also put up some of the most effective resistance to the Dutch attack on the Medway in 1667.

(AUTHOR’S PHOTOGRAPH)

THE SHAPES AND SIZES OF GUNS

Seventeenth-century naval guns were smooth bore muzzle-loaders. Gunfounders made them by using clay moulds, forming the bore by inserting a core close to the centre line of the mould. Guns were cast vertically to ensure that the metal was thickest and thus strongest at the breech.10 As only one gun could be formed from each mould, no two weapons, even from the same foundry, were ever completely identical, and the bores were not always placed correctly.11 They had a touch hole, and round trunnions, level with the lower part of the bore, protruded from both sides near the middle to enable them to be fitted onto carriages, and then to be elevated or depressed. Brass guns were additionally fitted with ‘dolphins’, usually two or four lifting handles shaped like the eponymous creature. A cascable (or large knob) was fitted on the closed end of the gun; this permitted the fixing of a breech rope, which restricted the recoil of the gun. The part of the bore nearest to the closed end, where the powder and shot were placed prior to firing, was known as the chamber. The part of the gun that enclosed the chamber was known as the breech; naturally, this was the thickest part, as it had to withstand the full force ofeach firing. Moving forward, the gun then consisted of sections called the ‘first reinforce’ (two-sevenths of the length),‘second reinforce’ (one-seventh) and ‘chase’ (four-sevenths), divided by strengthening rings around the barrel. At the rear of the ‘first reinforce’ was the ‘vent field’, which contained the touch hole. The gun widened again at the muzzle, where the open end was known as ‘the face’.12 Brass guns were more elaborately decorated than their iron counterparts. They often had two coats of arms, the sovereign’s and the master-general of Ordnance’s, on the first reinforce and chase. Iron guns usually had just a ‘Tudor rose’ on the second reinforce. After the Restoration, Charles II insisted on ‘CR’ being added to all iron guns and the master-general’s name to all brass guns, but in practice most iron guns of his reign had only a crown and rose cipher.13

Until the early eighteenth century, there was no detailed template for the dimensions of a particular kind of gun. Contracts specified weight and length, but the remainder was left to the expertise of the gunfounder.14 The bore was determined by the size of the ball intended for it, and one-twentieth was added to the bore for ‘windage’, to ensure that the ball did not jam on egress. Guns of even the same calibre varied considerably in length, but all large guns had to be long enough to fire far enough from the ship’s side to reduce the risk of the flash igniting the ship itself. Conversely, guns could not to be too long, as the space available for their recoil was limited by the beam of the ship and the various fittings on the centre line, such as masts and capstans, bearing in mind that they had to come far enough inboard to reload.15

TYPES OF GUN

Until the reign of Charles I, most naval guns were made of brass. Although much more expensive than iron, brass was stronger in tension, was less prone to leaking or bursting, and simply looked more impressive. But the differential between the costs of brass and iron increased steadily during the seventeenth century (by 1670 brass cost £150 a ton, iron £18), and during exactly the same period the technology of casting iron greatly improved. Iron wore better and did not bend after extensive use as brass did. By the 1620s and 1630s iron guns were starting to make an appearance, albeit still a limited one, on some ships of the fleet. The huge expansion of the fleet after 1649 meant that brass guns were far too expensive to equip the new ships, so large numbers of iron guns were ordered: 1,500 in February 1653, another 1,450 in the following July. Even so, brass was still favoured for the largest calibres and warships, and brass guns were often taken out of fortifications to make up any shortfall in a big ship’s armament. In 1668 the Ordnance Board began to order iron cannon-of-seven for the lower decks of the largest ships, and another important development took place in 1677, when the tight budget for the thirty new ships authorised in that year meant that all of them, including the largest, had to be equipped entirely with iron.16 Thereafter, the number of brass guns in service with the navy declined sharply, and iron became the dominant material in naval ordnance.17

The growing emphasis on weight of broadside led the British to look for weapons that would combine large calibre with relative lightness. The ‘drake’ was relatively short and thin, had a tapered bore, and was intended to take short charges. Although the drake allowed quite small ships to carry large guns, such as 32-pounders, it was unreliable in action, possessed a violent recoil, and had only a very short range, no more than 300 yards. Brass drakes proved unable to withstand the punishment that they received in the first Anglo-Dutch war; iron drakes continued in service for many years, although by the 1680s they had become increasingly unpopular.18 Even so, the increasing ability of the gunfounders to reduce the weight of guns of a given calibre contributed greatly to the ability of decision makers to cram warships with more and more guns, and to give British ships ever more powerful broadsides that their rivals were simply not able to live with.19

The main kinds of gun in service in the late seventeenth century were as follows.20

The 42-pounder (cannon-of-seven): The largest gun in British naval service, named for its seven-inch bore, was first fitted to the Sovereign of the Seas in 1637, subsequently forming the armament of the lower deck in all First Rates. It was usually of brass, though iron 42-pounders were brought into service from 1657 onwards, and in 1677 these were set at 9ft 6in long, weighing 65cwt. They fired a shot with a 6.7 inch diameter. They produced a massive recoil and were at the limits of contemporary technology: all twenty-two of the cannon-of-seven ordered for the Loyal London in 1666 burst during test firing.21

The 32-pounder (demi-cannon): This had a bore of 6.4 inches, and fired a shot with a diameter of 6.1. In the 1650s it became the standard lower deck weapon for large Third Rates, and in the 1670s it was also fitted to Second Rates. Most were between 8ft and 9ft and weighed about 55cwt.

The 24-pounder. This was originally exclusively a Dutch gun. Most of those in British service came from prizes taken in the first and second Anglo-Dutch wars, although some were subsequently cast locally and in 1665 forty were purchased from Sweden.22 By the 1670s and 1680s they had become the main armament for small Third Rates and large Fourths. The bore was 5.8 inches, the diameter of shot 5.5m. As with all other weapons of Dutch origin, the situation was complicated by the fact that the Dutch pound was about 9 per cent heavier than the English pound, although it seems that English shot was sometimes used in Dutch guns.23

The 18-pounder (culverin): This formed some 16 per cent of the navy’s total establishment. It was the middle deck gun on three-deckers, and the main armament on most Fourth Rates. Most were between 8ft 6in and 10ft long, weighing between 39 and 42cwt; the bore was 5.3m, the diameter of the shot 5in.

The 12-pounder. Another Dutch gun which entered British service following captures of prizes in the first war. It was used increasingly as the upper deck weapon on Third Rates, and in the 1680s it took on the same role on First and Second rates. It was quite long, being about 9ft or 10 ft. It had a bore of 4.6in and fired a shot with a 4.4m diameter.

The demi-culverin: Although these 9-pounder guns formed 34 per cent of the navy’s establishment in 1660, they declined markedly in the following decades. Until the mid-1670s the demi-culverin was the main armament on the upper deck of the three largest rates and on the lower decks of Fourths and Fifths, but the establishment of 1677 signalled a change in favour of the 12-pounder. Demi-culverins varied greatly in length and weight, from 5ft and ucwt to 10ft 6in and 36cwt. They had a bore of 4.2m and fired a shot with a diameter of 4in. Additionally, the cutt, a short version of the demi-culverin (and of the saker) was introduced in the 1650s.24

The 8-pounder. This was another Dutch gun, but it was never widely used other than in Dutch prizes and a few smaller Fourth and Fifth rates.

The 6-pounder. Another Dutch gun, used mainly on the upper decks of Fourth and Fifth rates.

The saker. There were large, ordinary and light sakers, which fired shot of 7%lb, 6lb and 5lb respectively. They were used as part of the upper deck armament on many ships, albeit in small numbers on the quarterdeck and forecastle. They were about 8ft long and weighed between 16 and 30cwt, though the foreshortened versions, or cutts, were much smaller.

The minion: A 4-pounder, this was largely out of favour during the period, but those that were fitted were used in the same way as the saker.

The 3-pounder. Another Dutch gun, it was used on the poop decks of large ships and the quarterdecks of smaller ones. It had a bore of 2.9in and fired a shot of 2.8in diameter.

The mortar. Mortars were introduced in the 1680s for service in the new bomb vessels, based on French precedents. The first mortars had a calibre of 12¼in and seem to have weighed about 36cwt.25 They were also used on some large ships in the 1690s.

Brass six pounder from the Stirling Castle, wrecked in the Great Storm of 1703. This gun was captured from the Dutch and has their East India Company (VOC) markings, along with the broad arrow indicating that it had been bored out to suit British shot, and had been proof tested for acceptance by the Ordnance Board.

(AUTHOR’S PHOTOGRAPH)

Bronze demi-culverin, cast by John Browne for the Sovereign of the Seas, and now displayed at the Explosion museum of ordnance at Woolwich.

(AUTHOR’S PHOTOGRAPH)

Drawing of a demi-cannon preserved at Barbados.

(RICHARD ENDSOR COLLECTION)

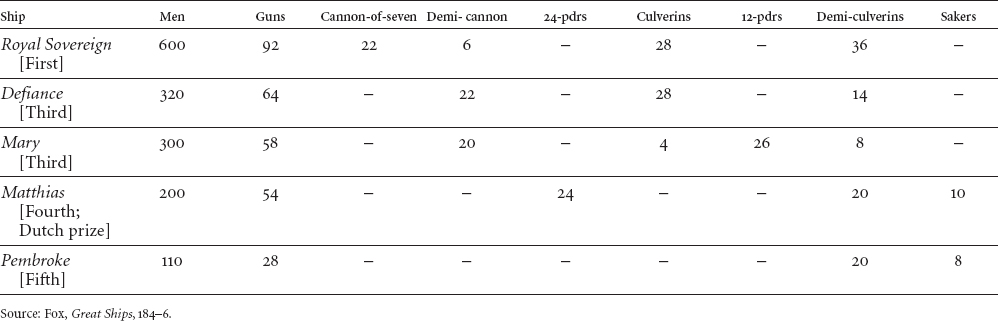

EXAMPLES OF ORDNANCE ALLOWANCES (1666 ESTABLISHMENT)

THE ‘RUPERTINO’ AND ‘PUNCHINELLO’ GUNS

Prince Rupert of the Rhine had particular interests in artillery and science, and in the early 1670s he and several collaborators (all members of the Royal Society) experimented with a new type of iron gun. He obtained the first of several patents in May 1671, and the first guns were fitted aboard the Cleveland Yacht later in the same year. The first large batch was delivered to the navy in the summer of 1673, when Rupert was in command of the fleet, and between then and 1676 more than 550 guns were made.26 The gun that he and his colleagues developed was annealed (i.e. cooled slowly) after casting, a process that produced a less brittle but rather more expensive weapon. The so-called ‘Rupertino’ guns were used to provide the entire armaments of the new ships Royal Charles, Royal James and Royal Oak, along with the Greyhound, which received sixteen Rupertino sakers.27 They were all inscribed with a motto proclaiming them to be Rupert’s invention, as well as the year and the name of the master of the Ordnance (Sir Thomas Chicheley); some, like those aboard the Greyhound, also seem to have been engraved with the emblem of the ship for which they were intended.28 Cost seems to have put paid to the experiment, although the death of one of Rupert’s partners and the growing political crisis of the late 1670s may also have played a part.29 Three of the guns formed part of the battery at Dover as late as 1750, and up to ten still survive in various locations. These include a unique example of a ‘Rupertino’ demi-cannon, which was salvaged from the wreck of the Stirling Castle on the Goodwin Sands during 2000.30

In April 1669 Pepys attended a test firing of a new gun designed by his friend Anthony Deane. Called a ‘punchinello’, this was shorter but heavier than existing guns. The test seemed to be successful: ‘against a gun more than as long and as heavy again, and charged with as much powder again, she carried the same bullet as strong to the mark, and nearer and above the mark at point-blank than theirs, and is more easily managed and recoils no more than that’.31 Unfortunately, there is no other record of Deane’s gun, which from this one surviving description of it sounds rather like a distant precursor of the eighteenth-century carronade.

No real attempts to standardise the armament of warships took place before the 1660s. Previously, ships had been allocated guns based on a consensus between the Navy and Ordnance boards over what was appropriate and what was available, so similar ships often ended up with very different armaments. Limited attempts to produce standardised establishments were made in 1664 and 1666, and these confirmed the trend towards more and heavier guns, allocating cannon-of-seven to the lower decks of all First Rates and demi-cannon to the lower decks of all Thirds and some Fourths.32 In 1674, according to his own account, Pepys brought the Navy and Ordnance boards together to create a permanent, fixed establishment for each ship. This project languished until 1677, when the commencement of the thirty new ships gave it a new urgency. It was approved by the king at a meeting of the Admiralty Commission in November 1677. The new scheme set out the principle that the weight of the guns should be in proportion to a ship’s tonnage. On most First and Second rates this ended up as a proportion of one-eighth (i.e. of weight of guns divided by tonnage), on Thirds it was about 0.115, on Fifths and Sixths about 0.110. These proportions tended to reduce slightly the weight of guns in some of the larger ships, especially Third Rates, as there was already a feeling that they had been overgunned in the 1650s and 1660s; however, the armament of many of the Fourth Rates increased.33 Pepys was very proud of the 1677 establishment, and of his part in its creation, but the Ordnance Office at once protested that it could be implemented only as far as the weapons actually in the inventory permitted. Moreover, there are several different versions of the 1677 establishment, and these do not entirely agree with each other. A new establishment was drawn up in 1685, and this took rather more account of the realities of what was in stock at the time, as well as slightly increasing the weight of ordnance on the larger ships. These establishments became the basis for the arming of the fleet throughout the French war of 1689–97.34

GUN CARRIAGES

Carriages were usually made of elm. They had to be light enough to permit recoil and (relative) ease of manoeuvre by the gun crews, high enough to place the gun at a convenient height for aiming and loading, and designed to permit elevation and depression. The common form of carriage during the seventeenth century was a ‘truck’, with four wheels (or trucks) and a bed of timber, on which were mounted the brackets that took the trunnions. Wedges were used for elevation. Though easy to use in some respects, the carriage could be difficult to control in battle, and there are many recorded instances of men being injured or killed by recoiling carriages.35

GUN IMPLEMENTS AND GUNNERS’ STORES

The guns on the lower decks protruded from gunports which could be closed by lids, usually hinged at the top edge, which made the space within habitable. When they were raised in battle, they gave some protection against small arms fire and grapeshot to the gunners within the hull. Ports were opened by port tackle, a rope fixed to a ringbolt in the centre of the port and fitted to blocks. Particularly when the ports were open, guns would be protected from the elements by tompions, wooden plugs fitted into their mouths. Breeching tackle consisted of a thick piece of rope fastened to ringbolts on each side of the ship, on either side of the gun, and spliced to the cascable. Gun tackle was used to run the guns in and out of the ports. Wads, made chiefly of‘junk’ (old rope), were used to ram home the shot and charge and to keep the shot in the barrel. The captain of the gun had a powder horn which he used to prime the gun, and then used a linstock (a specially fitted staff about three feet long) to apply a lighted match to the touch hole. After the gun had been fired, sponges were used to clean the barrel; these were often placed economically at one end of the thick piece of rope that had been used to ram home the charge. Gunners’ stores had to contain spares for virtually every part of the guns’ paraphernalia, and thus included some very large items, including spare tackle, and replacement beds and trucks for the carriages.36 When added to the value of the guns themselves, the powder, shot and small arms and the care of the magazine, the gunner’s office became in some ways the most important on the ship.