Privateers

FOR GOVERNMENTS in the early modern period, privateering was very much a doubled-edged sword. On the one hand, it provided a useful supplement to the state’s own naval resources by providing large numbers of ships dedicated solely to preying on the trade of the state’s enemies; and it served incidentally to give people from many walks of life and parts of the country a direct vested interest in the outcomes of maritime warfare which they might otherwise have lacked.* Privateers also raised money for the crown: their owners had to provide a £4,000 bond, which guaranteed both that they would stick to the rules and provide the king with 10 per cent of the takings.1 However, privateers also competed with the state’s navy for a finite pool of manpower. The largest English privateers of the period were of between 200 and 400 tons, often carrying between twenty and thirty guns and crews of over a hundred men. Admittedly, relatively few of these larger ships were set out. The great majority were smaller than a hundred tons, and some were very small indeed: the smallest set out during the second Anglo-Dutch war, the Speedwell, was of twelve tons and carried only two guns.2 Privateers were invariably heavily manned in relation to their size, partly to overwhelm their victims and partly to provide sufficient manpower for several prize crews. In 1673 the evocatively named Have At All Double Shallop, of just fourteen tons, was manned by thirty men, while Lord Clare’s Mary of Torbett, of a hundred tons, carried a hundred men. Such vessels were armed to the teeth. The Greyhound of twenty tons, set out by a Wivenhoe and London consortium in 1672, carried four cannon, thirty muskets, thirty cutlasses, thirty pistols, ten half pikes, eighty shot, forty grenades, two barrels of powder and 200 small shot.3

MANNING OF PRIVATEERS

There was no shortage of candidates for the many berths available on privateers. Inevitably, discipline was laxer than in the navy, and the chances of getting rich from prize money undoubtedly greater. Several privateers were stunningly successful: during the second war, the likes of Edward Lucy’s Lennox and Edward Manning’s Swallow took a string of prizes in the English Channel. Even a relatively small vessel, the Revenge of Llanelli, operating in a comparative backwater (the Bristol Channel), took four prizes within six months and made a tidy profit for her owners and crew.4 Unsurprisingly, the naval administration constantly encountered among many seamen a preference for service in privateers, and had to take steps to ensure that privateers were not set out en masse until the navy was properly manned. Some were set out only for finite periods of time, which did not clash with the main period of manning the fleet: the Flying Greyhound, in which Pepys was a partner, was commissioned on 25 October 1666 on condition that she would be returned to the crown for use as a fireship in the following spring.5 Letters of marque (essentially, royal licences to set out privaeers) might also be suspended temporarily to assist the manning of the fleet, as in 1666.6

In 1665, a second motive was apparent: restricting the number of English privateers was intended to encourage the Scots and Irish to set out their own, and in the case of Scotland, at least, this was undoubtedly successful.7 About sixty letters of marque were granted to Scots privateers during the second war, which compares favourably with the eighty-two issued in England, and Pepys believed that they caused more hurt to the Dutch than all of the main fleet’s actions during 1666.8 (Scottish privateers were better placed to fall on the important trades between Norway, the Baltic and the Netherlands.) However, the appeal of privateering was not constant, so, concomitantly, neither was its impact on naval recruitment. During the third war only some twenty-eight privateers were set out, a reflection perhaps of the ambivalence nationally to Charles II’s war aims and of the fact that the Dutch sent very little merchant shipping to sea for long periods of the war.

PRIVATEERS AND THE NAVY

Privateers could be a useful training ground for naval personnel, and several men who went on to become prominent naval captains gained their first experience of command in this way. Thomas Teddeman, captain of a 40-ton privateer in 1653, was a flag officer twelve years later; George Canning, who commanded the Penelope privateer in the second war, became the first captain of the revolutionary new galley-frigate James. Sir Frescheville Holles, one of the most charismatic officers of the Restoration period, gained his first seagoing experience by commanding the 300-ton privateer Panther in 1665.9 Richard Keigwin of Penzance had perhaps the most remarkable career of all. He was a naval lieutenant in 1665–6, commanded a privateer set out from his home town in 1667, returned to the navy as a fireship captain in 1672, went out to India and commanded an East India Company (EIC) ship, led a rebellion against the company during which he was proclaimed governor of Bombay, returned to England, became captain of the Fourth Rate Assistance in 1689, and was killed in the West Indies in 1690.10

Such transitions from privateering to the navy, and sometimes back again, were helped by the fact that privateers frequently operated alongside the state’s warships. In 1667 Sir Robert Holmes was given a prize ship for use as a privateer and kept her to windward of the squadron that he was commanding off Ireland, so that she would sweep up any available prizes for her owner’s private profit.11 Privateers sometimes operated as ad hoc convoy escorts if no warship was available; the Welsh privateer Revenge was convoying shipping in the Bristol Channel in 1667, and in 1693 Pepys noted that some Newcastle colliers had made an arrangement with two privateers to escort them safely to London.12 Privateers sometimes ‘hunted in packs’. Pepys’s Flying Greyhound operated with Prince Rupert’s two privateers, the Panther and Fanfan.13 The largest and most successful Channel Islands privateer of the second war, Andrew Bonamy’s Notre Dame of Mountcarmel (originally a French prize), was a Guernsey vessel that sometimes worked in tandem with a mainland privateer, Nicholas Carew’s Anthony. The Notre Dame had originally been a St Malo privateer, of thirty-six tons and five guns, taken after a bitter fight with the frigate Paradox in which well over half the privateer’s crew of forty-four were killed or mortally wounded. In October 1666 she was given as a gift to Hatton, the governor of Guernsey, and under Bonamy’s captaincy she became one of the most successful British privateers of the entire war – in barely a nine-month period.14 However, other privateering ‘teams’ were less successful, and eventually broke up in acrimonious arguments over the division of the spoils.15

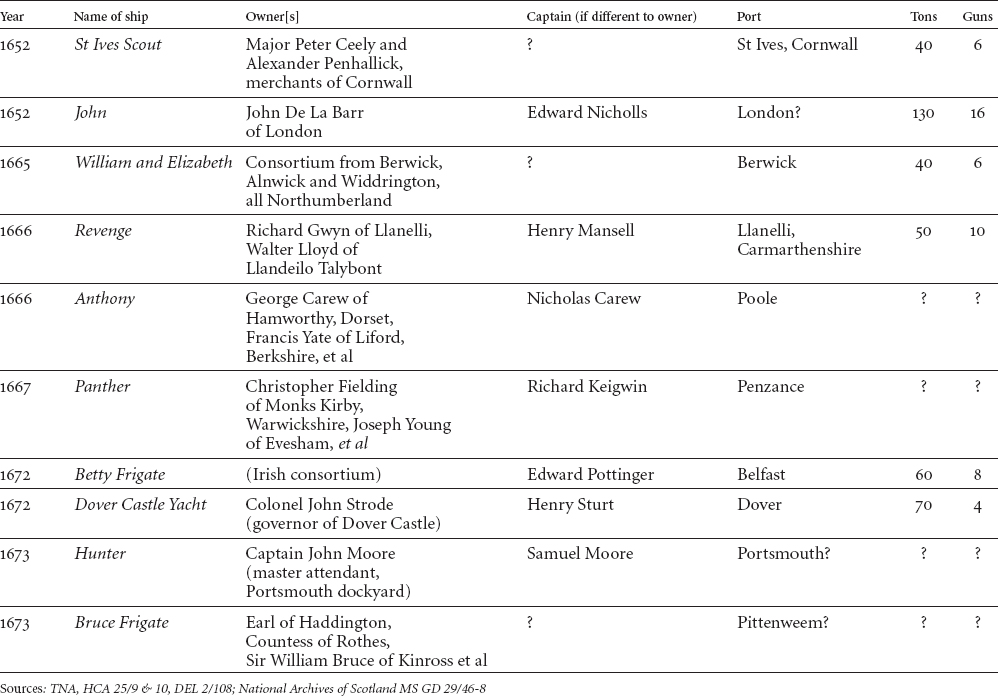

EXAMPLES OF BRITISH PRIVATEERS IN THE ANGLO-DUTCH WARS