Seamen’s Condition of Service

ENTRY AND RATING

UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, men did not join the navy per se. In theory, they signed on to serve in an individual ship, or under a particular captain, and they served in that ship only for the duration of her voyage, which could be as short as a few months guarding the herring boats in the North Sea, or as long as three or four years in the West or East Indies. Even in the late seventeenth century, though, it was already increasingly apparent that this was an elaborate fiction. When a man (or boy) stepped aboard a ship, his name was immediately entered on the ship’s pay and muster books, copies of which were sent off at regular intervals to a central naval administration, which eventually paid him. He received his food and drink from another arm of that administration, as did all his fellows who had signed on aboard other ships. He could be turned over from one ship to another, but still, in theory, he was not a full-time servant of the state, with continuous service as part of a permanent national institution.

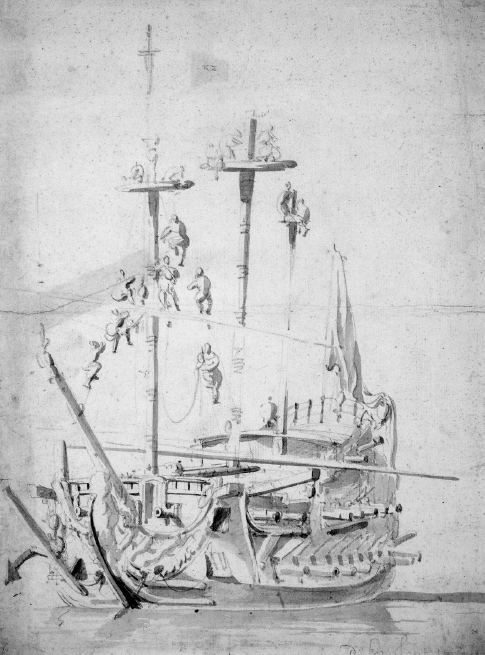

This Van de Velde drawing of the Constant Warwick gives a vivid impression of sailors’ work aloft.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, GREENWICH)

Once a man was entered aboard a ship, the officers were meant to decide whether he should be rated as an able or an ordinary seaman. In practice, it was virtually impossible to do this before the ship actually sailed and men could be assessed objectively. Able seamen were to be ‘fit for helm, lead, top, and yards’, all skilled tasks that demanded considerable competence.1 Taking the helm, which entailed holding and heaving the whipstaff, controlled the movement of the ship, and although in theory the helmsman would always be under the supervision of an officer, he might still need to exercise his own discretion in emergencies and to keep the wind in the sails. The ‘lead’ entailed heaving the lead over the side to take soundings; giving an accurate reading would be essential to the safety of the ship. Because of the responsibility involved, the 1663 General Instructions to Captains specified that no man could be rated able unless he was at least twenty and had been at sea for at least five years.2 An ordinary seaman’s duties could hardly have been described as unskilled, as he had to work aloft, ‘learn the ropes’, heave on cables as part of a team, perhaps man a gun and master the use of small arms, such as a pike or musket. Pepys sometimes compared the range of skills that had to be possessed by seamen, and the dangers to which they were exposed, to those of landsmen, particularly soldiers, and although there was an element of special pleading in the comparisons he made, he was undoubtedly right.3

PAY

On paper, a naval seaman’s pay was respectable enough: from 1653 onwards, it was nineteenth shillings a month for an ordinary seaman, twenty-four shillings for an able seaman. This was roughly equivalent to a soldier’s pay and to that of farm labourers, but it was not on a par with the wages available in the merchant service*. Seamen naturally expected to be paid in full at the end of each expedition, but the administration rarely had the funds to permit such prompt payment. Crews accumulated substantial arrears of pay; in 1662, Pepys was still paying off ships that had wages due from before the Restoration, and by 1667, after the chaotic breakdown of naval finances over the previous few months, several ships had three or four years’ arrears due to them.4 Peace was no guarantee of better pay. In 1683 the crews of the Mary and Cleveland yachts had six years’ wages due to them, and ships on foreign stations often had similar arrears; in general, ships operating singly or small detached squadrons were paid later than the great ships of the main fleet, which simply carried more ‘clout’ in such matters.5 In such circumstances, families had to rely on credit, or on the charity of others, such as relatives or neighbours.6 Pepys witnessed the iniquities of this relatively early in his career, when he paid the Guernsey at Deptford in March 1662: ‘the poor men have most of them been forced to borrow all the money due for their wages before they receive it, and that at a dear rate, God knows. So that many of them had very little to receive at the table – which grieved me to see it.’7

In extremis, the administration resorted instead to issuing tickets, essentially IOUs (with counterfoils from 1654 onwards, to reduce the possibility of fraud) that could be drawn on the treasurer of the navy. Desperate for cash in hand, seamen frequently resorted to brokers, often women, who would buy the tickets, albeit at a ‘commission’ of 25 per cent or more; in November 1665 Pepys described ‘how poor wretches go hourly up and down Lombard Street with their tickets offering them for sale’.8 Landlords, shopkeepers and alehouse-keepers all accepted tickets as payment, and then besieged the Navy Office for satisfaction.9 The system was wide open to even more blatant forms of abuse: in 1676 five women were committed to Newgate for counterfeiting tickets due to seamen on the Eagle.10 Seamen deeply resented the recourse to tickets and sometimes reacted violently, particularly in 1666–7, when several attacks took place against the ticket office and its staff. In October 1666 the Navy Board ordered twelve firelock muskets to defend the office ‘against any outrage in case of a mutiny’ caused by ‘the present great refractoriness and tumultuousness of the seamen’.11 The heavy dependence on payment by tickets during the second Anglo-Dutch war, itself a sure sign that the navy’s finances were in dire straits, eventually inspired one of the most famous passages in the whole of Pepys’s diary, written on 14 June 1667 during the Dutch attack on Chatham:

… many Englishmen [were] on board the Dutch ships, speaking to one another in English, and that they did cry and say, ‘We did heretofore fight for tickets; now we fight for Dollars!’ .they said that they had their tickets signed (and showed some) and that now they came to have them paid, and would have them paid before they parted. And several seamen came this morning to me to tell me that if I would get their tickets paid, they would go and do all they could against the Dutch; but otherwise they would not venture being killed and lose all they have already fought for – so that I was forced to try what I could do to get them paid.12

There were cases of good and prompt payment, but these were so rare that they tended to be worthy of special comment. In August 1671, John Narbrough went along to the treasury office in Broad Street with the whole of the ship’s company of the Sweepstakes, which had returned to Deptford only four days earlier from a two-year voyage to the Pacific. Narbrough enthused, ‘I never saw better payment in my days. This night we parted and went every man his way with his money in his pocket. All the seamen were mighty well satisfied.’.13

PRIZE MONEY, PENSIONS AND GRATUITIES

Prize money was less important to the seamen of Pepys’s time than it was to those of Nelson’s. Although there were formal rules for the distribution of prize money among the crew,* the opportunities for taking prizes were fewer. The Dutch wars were comparatively short, and although many prizes were taken in the first war in particular, a large number of them were snapped up by privateers. Also, proportionately more men served in very large ships of the First to Third rates, which were inherently less likely to take prizes than the comparatively small number of Fourth to Sixth rates, and in any case the formula for distributing prize money was weighted heavily in favour of the officers.14

Although there were no naval pensions per se, provision was made for those who were wounded or killed in service, and for their dependants. The bounty regulations of 1665 gave £5 to the widow of a man killed in the king’s service, and £2 to each child.15 In 1673 a new scale was adopted, which gave widows a gratuity equal to eleven months of the husband’s pay, with an additional third to each unmarried orphan. If the man left no widow, his mother would be entitled to the same gratuity, as long as she was an indigent widow over fifty years old.16 Wounded men were able to apply to the Chatham Chest, which paid fixed rates for different wounds. Loss of a leg or an arm entitled a man to £6 13s 4d as a lump sum, and the same annually for life. This doubled if both legs were lost, and increased to £15 for the loss of both arms, as the man would then not be able to get any other livelihood. Loss of an eye entitled a man to £4 a year.17 Some men depended on the Chest for decades; in 1676, the longest-serving pensioner had been drawing on its resources for fifty-six years.18

REWARDS AND MEDALS

Seamen who performed exceptional service might sometimes receive financial rewards or medals. These had long been awarded to officers, but from about 1649 or 1650 onwards Parliament awarded them to men as well. The first grant for which definite evidence exists gave every man of the Adventure a medal worth five shillings for an action against five ships off Harwich in 1650 (but the captain’s medal was valued at £50). Only 169 medals were issued during the Anglo-Dutch war, and many of those were intended for officers, but a clear precedent had been established.19 In 1668 a midshipman and ten seamen shared £100 for their actions in the West Indies, and in 1673 a seaman received £6 for fending off an attack by a Dutch ship.20 The men who took part in the successful attack on Tripoli in 1676 received ten pieces-of-eight each from their admiral, Sir John Narbrough, and on their return home Charles II augmented this with a further grant of £10 per man, while the captains got medals valued at about £60 each. Lieutenant Cloudesley Shovell, who had led the attack, was granted one valued at £100, but care was taken to ensure that this did not establish a precedent.21

It was still possible to work one’s way up from the very bottom, proceed through the ranks and obtain a commission, but much depended on luck and, above all, on being promoted by an influential patron. Isaac Townsend, who eventually became a commissioner of the navy, was Captain Hugh Ridley’s servant on the Wivenhoe in 1675, then successively coxswain, able seaman and midshipman aboard her. He was still a midshipman under Ridley aboard the guardship America in 1685, by which time he was twenty-seven, but then he attracted the patronage of Admiral Sir Roger Strickland, and he finally became a lieutenant two years later.22 Sir John Norris, who served as admiral of the fleet in the 1740s, began his naval service in 1680, at the age of nine or ten, as a captain’s servant aboard the Gloucester Hulk. In the following year he went to sea in the Sapphire in the same capacity under Cloudesley Shovell; he was rated an able seaman in 1686, followed by midshipman in 1687, and eventually obtained a command in 1690.23 But very few men had careers that followed such apparently inevitable paths to promotion and high rank. More typical was the service of Richard Dickenson, who was probably the son of a captain of the same name, aboard the Mary in 1677–9; initially a quarter gunner, he rose to become a midshipman before sinking back to able seaman by the end of the commission.24 Thomas Couch served as a petty officer for well over thirty years, beginning in 1653 and having spells as a quartermaster, yeoman and boatswain’s mate, while it took Robert Robinson twenty-three years of service as a midshipman or master’s mate before he finally obtained his first post as a master.25

RETIREMENT

The nature of the trade dictated that most seamen were relatively young men, and there was no formal system of retirement or pensions for those who were not. Nevertheless, many men continued to serve long past the age at which seventeenth-century men were considered to become ‘old’ (generally in their late forties or early fifties). In some respects the administration’s attitude was remarkably charitable, displaying a willingness to retain men who would otherwise have been unlikely to make a living ashore, and whom the far more draconian merchant service would simply not accept. Positions on ships laid up in ordinary could be literally ‘jobs for life’, especially during the long peace of the 1670s and 1680s when most of the greatest ships in the navy never went to sea for years on end. By 1685 the armourer of the Sovereign was eighty; many other men acting as shipkeepers aboard the ships in ordinary were aged between forty and seventy, and fifty years earlier a boatswain of one of the ships in ordinary had been a centenarian.26 To ensure that maintenance of these floating geriatric homes could be carried out efficiently, these older men were balanced by large numbers of teenagers and men in their early twenties, most of whom were entered as indentured servants to the standing officers.27 In 1674 the administration also laid down quotas for maimed men, who were to be borne aboard warships to give them a means of livelihood and to recognise their sacrifice in the state’s service. A ship with a complement of sixty or fewer would carry one maimed man, one with a crew of between sixty-one and a hundred would carry two, and thereafter one maimed man would be allowed for every fifty able-bodied men in the crew.28 Those who were too badly wounded even for this role, or who were blind, could petition for places as grindstone turners ashore.29

Almshouses like Trinity Hospital, Greenwich, founded in 1614, were among the few options available to seamen who became too old to pursue their trade.

(AUTHOR’S PHOTOGRAPH)

Other elderly seamen obtained pensions from the Chatham Chest, sought almsmen’s places, or threw themselves onto the charity of their local parishes.* A few discovered rather different, and not necessarily legal, ways of making a living. William Ferguson, the son of King Charles II’s shoemaker, served throughout the second Anglo-Dutch war, but he was forced to leave the navy after breaking the thumb of his right hand. He became a pickpocket (presumably a lefthanded one) but was eventually caught and sentenced to death; even so, his previous good service saved him from the gallows.30 For some, though, leaving the world that they had known all their lives was simply inconceivable. Robert Cook claimed to have been a seaman in the navy for at least sixty years when, in 1680, he sought a sinecure on a yacht in the ordinary at Deptford, or else a place on shore there.31

* See Part Five, Chapter 19, p108.

* See Part Four, Chapter 16, p104.