7

And hope, with furtive eyes and grappling fist Flounders in the mud. O Jesus, make it stop!

—Siegfried Sassoon

A little over a month after the end of the Caillaux trial, German cavalry patrols roamed within eight miles of Paris. The war happened in a world discontinuous with the one in which that sordid little story counted as big news. The year split into before and after, and contemporaries would never assimilate the totality of what was lost on the far side. The dedication a Belgian poet wrote to a 1915 book, “With emotion, to the man I used to be,” covered the experience of a generation.*

It was not only the inconceivable fact of war after a “century of peace” and after Europe had achieved a degree of financial integration that a 1910 book that sold two million copies had made war unthinkable; it was the immediate slaughter on a nuclear scale that shattered the compass of thought and feeling. Bull Run, the first full-scale engagement of the American Civil War, was fought three months after the shelling of Fort Sumter, and the death toll was light compared to Antietam and Gettysburg. The major battles of World War II happened years into it. But, though it lasted another four years, World War I was never bloodier than between August 1914 and January 1915, when over a million men died in battle.1

They were sacrificial offerings to a “cult of the offensive” that lent general staffs the nimbus of “strategy,” wonder-working schemes sold to governments for winning on the quick. The cult of the offensive belongs to 19194’s lost history. For while at least one of these strategies, Germany’s Schlieffen Plan, is famous, their back story in institutional politics is forgotten, and why they failed with it.2

Militarily what the historian Stig Förster has written of Schlieffen also applies to the war plans of the other Great Powers—they made “no sense.” In 1914 defense was dominant. That was the lesson taught by the Franco-Prussian War, in which the Prussian Guard suffered seven thousand casualties in twenty minutes attacking entrenched French infantry at St. Privat, as well as by the sanguinary battles of the Boer War and the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–05—the lesson taught by the heaps of bodies that repeating rifles, rapid-firing artillery, and above all machine guns spewing six hundred bullets a minute, “as much ammunition as had previously been fired by half a battalion of troops,” had decisively advantaged the defense over the offense. The generals were not fools. Yet when recent history shouted defense, they insisted “Attack is the best defense.”3

In part they were reverting to type. Militaries prefer offense because it makes soldiers “specialists in victory” whereas defense makes them “specialists in attrition.” Attrition takes time, it means a long war, it asks too much of politicians and publics. “[Long] wars are impossible at a time when the existence of a nation is founded upon the uninterrupted progress of commerce and industry,” the eponymous von Schlieffen, the chief of staff of the German army from 1891 to 1905, reasoned. “A strategy of attrition cannot be conducted when the maintenance of millions depends on the expenditure of billions.”4

In Germany the “demi-god” status of the officer corps rested on Bismarck’s three short successful wars fought in six years. The General Staff was expected to match that legacy in 1914 in a strategic environment inimical to it. The generals had three alternatives to aggressive war. One was politically untenable, one psychologically inconceivable, one strategically impossible.

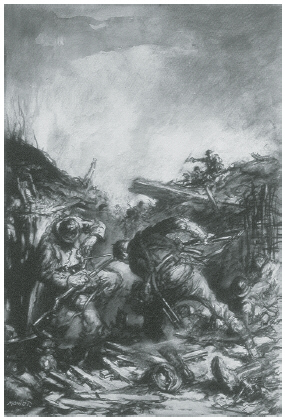

“Sturmangriff” (Assault) by Ernst Barlach

To solve the problem lit up by Bismarck’s map of Africa—France on one side, Russia on the other, Germany in the middle—Germany could have transformed itself into Sparta. Liberal Germany could have been snuffed out under the spiked helmet, socialist workers conscripted, Prussian Junkers taxed. Preparing Germans for “a long war against superior enemies,” the generals could have demanded the militarization of the state, economy, and society, something even Hitler didn’t dare in peacetime.5

Or Germany could have achieved Peter Durnovo’s dream—détente with Russia. A band of generals close to retirement could have told the kaiser: We do not know how to win a two-front war. Conceding that truth, however, would have “challenged the self-image of the general staff officers and questioned the entire position of the army in the structure of the Reich.”6

If Germany could not escape a two-front war with diplomacy, the general who led Bismarck’s wars, Helmuth von Moltke the elder, recommended standing on the defensive in the west while attacking Russia in the east. Despite its laureled source, considerations of national strategy militated against that idea. “Offense in the East and Defense in the West would have implied that we expected at best a draw,” Bethmann Hollweg, Germany’s wartime chancellor, wrote in his memoirs. “With such a slogan no army and no nation could be led into a struggle for its existence.”7

Privately, the broodier sort of generals foresaw a long-lasting war, a “mutual tearing to pieces,” in the words of Moltke the elder’s nephew and Schlieffen’s successor as chief of staff, Moltke the younger. To the War Ministry in 1912, the younger accurately described Germany’s two-front challenge: “We will have to be ready to fight a lengthy campaign with numerous, hard, lengthy battles until we defeat one of our enemies.” Evidence like that has changed the minds of historians, who no longer see Moltke as a votary of “the short-war illusion.” Calculating that “specialists in victory” were likelier to gain bigger budgets than “specialists in attrition,” Moltke and his generals gave “lip service to the short war panacea” when talking to officials like Bethmann, who promised Germans that the war would be a “brief storm.” Deceived into believing that victory was assured, Germany’s civilian leaders “never felt the need to rethink” whether war was an option for Germany. For confining their candid gloom to their diaries and letters—the war would be “a general European massacre,” Moltke wrote his wife—Förster indicts the soldiers who launched the war for their “almost criminal lack of responsibility.”8

Just as Stig Förster, using materials from the former East German military archive, has prompted a revision of the “short-war illusion,” so Terence Zuber, a retired U.S. Army officer and German-trained historian, has challenged an even greater shibboleth, the Schlieffen plan.

Until Zuber unsettled the field it was universally accepted that Germany followed Schlieffen’s short-war strategy in August 1914. The “Schlieffen Plan” envisioned a gray flood sweeping through Belgium into northern France and then arcing around Paris and smashing the French army up against its own fortifications on France’s western border. On the basis of evidence he discovered in the East German archives, Zuber contends that the Schlieffen Plan was not Germany’s strategy in 1914 and in a series of books and papers published since 1999 has defended his interpretation against all comers. “All the older literature needs to be revised in the light of Zuber,” concluded Hew Strachan, a preeminent historian of World War I.9

The memorandum Schlieffen wrote upon retiring as chief of staff in the winter of 1905–06, in the words of a scholar refereeing the debate, “was not the blueprint for war in 1905 or 1914, or even a war plan at all, but rather an elaborate ploy to increase the size of the German army.” Schlieffen fashioned a miracle strategy to defeat the French army and win the war in forty days. But the troops to execute it did not exist and the meticulous Schlieffen never tested it in a war game. The plan depended on “ghost divisions” that it was the government’s urgent duty to animate by implementing “universal conscription,” which, Schlieffen wrote, “we invented … and demonstrated to other nations the necessity to introduce” only to “relent in our own endeavors.” If the War Ministry did not take this politically risky step (which would fill out the army with Social Democrats, precluding the kaiser from using it to “decapitate” the Social Democrats), Germany would lose the war. It didn’t and Germany did. The Schlieffen ploy failed.10

As for the “Schlieffen Plan,” the generals “invented” it after the war to rescue the mystique of Prussian militarism from the disgrace of defeat. The German army lost the battle of the Marne in September 1914 because Moltke failed to swing the German rightwing around Paris to envelop the French army from the west. This deviation from the master’s blueprint cost Germany the war. That was the legend of the Schlieffen Plan spun by the General Staff and accepted in classic works like Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August (1962). In truth, according to Zuber, “There never was a ‘Schlieffen Plan.’ ”11

Moltke unleashed his offensive against France in August 1914 not from an expectation of victory in one battle (and certainly not by following the super-secret “Schlieffen Plan” then in the possession of Schlieffen’s two elderly daughters!), but out of fear that Germany would lose its power if it waited.* War was “now or never.” “The prospect of the future seriously worried him,” the German Foreign Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow wrote of a March 1914 meeting with Moltke. “Russia will have completed her armaments in 2 to 3 years. The military superiority of our enemies would be so great then that he did not know how he would cope with them.” He asked Jagow “to gear our policy to an early unleashing of war.” The assassination of Franz Ferdinand in June gave Moltke “his chance,” Förster writes. “He would not allow it to slip away.”12

Geography lent the cult of the offensive a surface plausibility in Germany. To survive a two-front war, it had to subdue one of its enemies before turning on the other; that, say Zuber’s critics, was the strategic dilemma to which the desperate ambition of Schlieffen’s valedictory answered. But in France the absurdity of the cult should have been patent. Under the political necessity of respecting Belgium’s neutrality (or else forfeit Britain’s support) until the last minute, it needed to adopt a “counteroffensive” strategy—defense followed by counterattack. The politics of the French army, however, vetoed defense.13

In the wake of the Dreyfus Affair, French politicians on the left had sought to “republicanize” an army hierarchy that had covered up a miscarriage of justice against a Jewish staff officer falsely accused of spying for Germany: “Military values of unthinking obedience and blind loyalty seemed irreconcilable with the democratic values of due process, tolerance, equality, and the rule of reason.”14

Socialists like Jean Jaurès wanted France to defend itself with an army of citizen reservists. Reformers within the military wanted to use reservists as front line troops to democratize the army and allow France to compensate for its demographic inferiority vis-à-vis Germany. While traditional French strategy called for charging across the Alsace-Lorraine frontier at the first shot, the reformers favored waiting until the Germans committed themselves before counterattacking.15

The unreconstructed officer corps seethed over these incursions on its institutional autonomy. It feared that reserves would weaken its control over the army, resented a reformed training regime to instill “discipline via respect” instead of via brutality, and watched with dismay as the number of applicants for St. Cyr, the prestigious military academy, declined from 3,400 in 1892 to 800 in 1912.16

The nationalist revival after Agadir gave the military establishment an opening to undo republicanization and trump citizen-based defense. Since 1904 French intelligence had known that to increase their offensive punch the Germans planned to use reserves as front line troops, but the French General Staff “manufactured fake German documents” showing the opposite. The enemy won’t use reserves, they argued, and neither should we.17

To replace reservists, the generals successfully lobbied to expand the regular army by adding an extra year to the two-term of French conscripts. Plucked overnight from civilian life, reservists were suited to defense but only regulars were regarded as equal to the attack. Therefore, to keep the door shut against the reserves, the General scrapped the reformer’s “counteroffensive” strategy in favor of the offensive à outrance—the offensive at all costs.

Vitalist cant about French élan and the bayonet charge prevailing against soulless German machine guns masked a bureaucratic coup. Staff officers suspected of defense were forced out or transferred to field commands. Even standing on the defensive long enough to read a German thrust and then counterattack was now deemed “unworthy of the French character.”

The French army “no longer knows any other law than the offensive,” General Joffre, the chief of staff appointed under Joseph Caillaux, avowed. In the first six weeks of the war, 329,000 Frenchman became casualties obeying a law decreed to defend the French army against the values of the French republic. When Clemenceau later remarked that war was too important to be left to the generals, he knew what he was talking about.18

Fighting from trenches, the Boers had raked attacking British regulars during the war of 1899–1902; yet British generals dismissed the unpleasantness on the South African veld as inapplicable to the European battlefield and insulting to the British fighting man. As General W. G. Knox, speaking for his kind, stipulated, “The defensive is never an acceptable role to the Briton, and he makes little or no study of it.” For the aristocratic British officer corps, “The Boer fondness for trenches was in fact seen as evidence of their lack of breeding—real gentlemen would stand and fight.”19

Russia had defeated Napoleon by drawing him into its depths, but it too succumbed to the cult, adopting “an impossibly offensive strategy” involving dual attacks on Germany and Austria. General V. A. Sukhomlinov, the minister of war, called on the army to emulate its enemies by “dealing rapid and decisive blows.”20

The generals created the cult of offensive to win the inside game with their governments and then became its prisoners. In August 1914 the clashing armies followed the same playbook of self-slaughter. By mid-September 1914, a mere six weeks after the opening of hostilities, the attacks inspired by the cult—the German march on Paris, the French offensive à outrance into Lorraine, the Russian invasion of East Prussia, and the Austrian incursion into Serbia—had ended in slaughter and stalemate. Reflecting on the last offensive of the year, the German attempt to break the Allied lines in Belgium and seize the Channel ports, the Times of London observed on December 2 that “The Battle of Flanders died of the spade.” So did the offensive.21

“We were all blind,” General Erich von Falkenhayn, who succeeded von Moltke in September and who ordered the Flanders offensive, confided to a visiting military attaché. “The Russo-Japanese War represented an opportunity for us to learn about the tactical consequences of the new weapons and combat conditions. Instead we believed that the trench warfare that was characteristic of this war was due to logistical problems and the national traditions of the belligerents … The force of the defensive is unbelievable!”22

Alsatian soldiers of the Ninety-ninth Infantry Regiment who had endured the “Wackes” taunts of Lieutenant von Forstner in Zabern were used—and used up—in Falkenhayn’s attacks around Ypres. Some tried to desert, but were shot running toward the French lines. Caught in no-man’s-land, they stood for the 380,000 men from Alsace-Lorraine who fought in the German army. Treated as “the enemy in our ranks,” eighty in ten thousand deserted compared to one in ten thousand among other German men. The wholesale transfer of units to the eastern front, where they could not desert, destroyed morale, and the last months of the war saw thousands of soldiers from Alsace-Lorraine mutiny at the Beverloo training camp in Belgium and only expedients like removing their rifles’ springs kept other units from following suit.*23

Under Falkenhayn, the Germans were the first to wield the spade, digging in above the Ainse River to check the Allied counteroffensive that ended the Battle of the Marne. This shift to the defensive “must be considered the real turning point of the war.” Near noon on September 3, just as the French were encountering the wire that the Germans had strung in front of their trenches, an aide to a French general opened his office door. “General,” he inquired, “do you want lunch to be prepared?” “Lunch!” the general snorted. “We shall be sleeping twelve miles from here on the Suippe. I certainly hope we aren’t staying more than an hour in this spot!” They stayed four years.24

In the east, the war of movement continued, but from the North Sea coast of Belgium to the Swiss border, the exhausted armies dug in, creating “a temporary crisis in the business of war,” in the words of Marshal Ferdinand Foch. “Some way had to be found which would enable the offensive to surmount the obstacle and break through the shield which the ground everywhere afforded the soldier,” Foch wrote in his Memoirs, stating the riddle of “the trenches,” the defining battlescape of World War I.25

A man in a trench was almost invulnerable to rifle and machine-gun fire. To kill or wound him with a shell required a lucky shot; by one contemporary estimate, it took 329 shells to hit one German soldier. To clear the trench a hand grenade had to be thrown or shot into it. But to get within range—60 to 120 feet—required crossing no-man’s-land alive, possible only for small groups mounting nocturnal trench raids, and not for masses of men advancing in daylight against a “storm of steel” from machine guns and artillery. Mobility and mass had ruled warfare since antiquity. Opponents were either flanked or crushed. Trench warfare mocked these principles. If, trying to defeat the Allies before the million-man American Army took the field, the Germans had not raised up out of their trenches and taken the offensive in the spring of 1918, the war would have lasted a year or more longer.26

Mud was the soldiers’ shield. European man tried to cheat death by submerging himself in the “greasy tide” of rainy, thin-soiled Flanders and Picardy. Three French soldiers speak for millions.

“The front-line trench is a mud-colored stream, but an unmoving stream where the current clings to the banks,” one wrote. “You go down into it, you slip in gently … At first the molecules of this substance part, then you can feel them return together and hold on with a tenacity against which nothing can prevail.”

“Sometimes the two lips of the trench come together yearningly and meet in an appalling kiss, the wattle sides collapsing in the embrace,” another observed. “Twenty times over you have patched up this mass with wattles, yet it slides and drops down. Stakes bend and break … Duckboards float, and then sink into the mire. Everything disappears into this ponderous liquid: men would disappear into it too if it were deeper.”

To yet another, writing in a soldier-edited “trench paper,” the mud seemed alive—and hungry: “At night, crouching in a shell-hole and filling it, the mud watches, like an enormous octopus. The victim arrives. It throws its poisonous slobber out at him, blinds him, closes round him, buries him … For men die of mud, as they die of bullets, but more horribly. Mud is where men sink and—what is worse—the soul sinks … Look, there, there are flecks of red on that pool of mud—blood from a wounded man. Hell is not fire, that would not be the ultimate in suffering. Hell is mud!”27

“Debout Les Morts!” (1917) (The Dead Rise Up!) by Frans Masereel

On his first night in the trenches, Robert Graves “saw a man lying on his face in a machine-gun shelter.”

I stopped and said: “Stand-to, there.” I flashed my torch on him and saw his foot was bare. The machine-gunner beside him said: “No good talking to him, sir.” I asked: “What’s wrong? What’s he taken his boot and sock off for?” I was ready for anything wrong in the trenches. “Look for yourself, sir,” he said. I shook the man by the arm and noticed suddenly that the back of his head was blown out. The first corpse I saw in France was this suicide. He had taken off his boot and sock to pull the trigger of his rifle with his toe; the muzzle was in his mouth.28

The mutual siege warfare of the trenches was a psychic Calvary. “All poilus have suffered from le cafard,” a poilu, the French “grunt,” testified, using an expression for overmastering misery “which has no precise linguistic equivalent in the English vocabulary of the Great War.” To be alive was to be afraid—of snipers, shells, mines, and gas; of drowning in mud, burning in liquid fire, and freezing in snow; of the enemy in front of you and the firing squad behind; of lice and rats, pneumonia, and typhus; of cowardice, hysteria, madness, and suicide.29

“Toter Sapenpost” (1924) (Dead Sapenpost) by Otto Dix

Graves’s great fear was of being hit by “aimed fire” traceable to a marksman’s malevolent intent. The least likely way to die in the war, the bayonet thrust in the gut, was the most terrifying. More rational was the terror instilled by “the monstrous anger of the guns,” as the poet Wilfred Owen personified artillery. Unaimed shellfire was the major killer in the trenches. Under saturation bombardment, there was no escape. For nine straight hours, on February 21, 1916, at Verdun, eight hundred German artillery pieces fired forty shells a minute on the French positions. “I believe I have found a comparison that conveys what I, in common with all the rest who went through the war, experienced in situations like this,” Ernst Jünger wrote. “It is as if one were tied to a post and threatened by a fellow swinging a sledgehammer. Now the hammer is swung back for the blow, now it whirls forward, just missing your skull, it sends the splinters flying from the post once more. That is exactly what it feels like to be exposed to heavy shelling without cover.”30

Jünger’s image captures the emotional trauma specific to trench warfare. In his 1918 book War Neurosis the psychiatrist John T. MacCurdy hypothesized that industrial warfare was uniquely stressful because soldiers were forced to “remain for days, weeks, even months, in a narrow trench or stuffy dugout, exposed to constant danger of the most fearful kind … which comes from some unseen force, and against which no personal agility or wit is of any avail.” Nor, unless in hand-to-hand combat, could the men “retaliate in any personal way.” Their memories were seared with inadmissible fear and inexpressible rage. The worst sufferers from war neurosis or “shell-shock,” as a Lancet article labeled it in early 1915, were the defenseless artillery spotters who hung over the battlefield in balloons while the enemy fired shot after unanswered shot at them. “Medical officers at the front were forced to recognize that more men broke down in war because they were not allowed to kill than collapsed under the strain of killing,” observes the historian Joanna Bourke. To spare himself, perhaps Graves’s barefoot suicide needed to turn his death-will on a German.31

Soldiers could look away from terrible sights; there was no escape from the pounding nightmare of the guns. Of the firing of a giant mortar, an American correspondent with the German army in Lorraine reported: “There was a rush, a rumble, and a groaning—and you were conscious of all three at once … The blue sky vanished in a crimson flash … and then there was a remote and not unpleasant whistling in the air. The shell was on its way to the enemy.” What did it sound like to him? “You hear a bang in the distance and then a hum coming nearer and nearer until it becomes a whistle,” a British soldier remembered. “Then you hear nothing for fractions of a second until the explosion.” “The lump of metal that will crush you into a shapeless nothing may have started on its course,” wrote Ernst Jünger, recalling the thought that filled his mind while he “cower[ed] … alone in his hole” during a bombardment. “Your discomfort is concentrated on your ear, that tries to distinguish amid the uproar the swirl of your own death rushing near.” Paradoxically, the shells that couldn’t be heard, those fired from trench mortars just across no-man’s-land, were the likeliest to kill. Terrifying as the din was, men had more to fear from the silence.32

“The Grenade” (1915) by Max Beckmann

Artillery broke men; it could not break the trench barrier. A rain of shells might bury a stretch, but not men guarding it. Carrying their machine guns and rifles, they could ride out the bombardment in deep dugouts built into the inner walls of the trench, then surface in time to decimate the attacking infantry. The machine gun, which had necessitated the trench, could not break it. The grenade was “an excellent weapon to clear out the trenches that assaulting columns are attacking,” in the words of Tactics and Duties for Trench Fighting, a U.S. Army manual. Of flamethrowers, exploited by the Germans in their 1918 breakout attacks, Tactics and Duties bleakly concluded: “It is impossible to withstand a liquid fire attack if the operators succeed in coming within sixty yards” of the trench. “The only means of combating such an attack is to evacuate.” Grenades and flamethrowers were tactical weapons. Gas was potentially strategic.33

In April 1915, the Germans released a 150-metric-ton cloud of chlorine along a seven-mile front near Ypres. The cloud slowly wafted across no-man’s-land, turning from white to yellow-green as it crept closer to the two divisions of Franco-Algerian soldiers holding the line. Choking for life, they panicked and ran, German infantry in pursuit. “We had seen everything—shells, tear-gas, woodland demolished, the black tearing mines falling in fours, the most terrible wounds and the most murderous avalanches of metal—but nothing can compare with this … death-cloud that enveloped us,” one poilu wrote in a trench paper. The Germans captured two thousand prisoners and fifty-one guns but had not accumulated the reserves to convert this tactical success into a breakthrough, a failure that gave rise to the myth of the “missed opportunity.” (“After the war, many of the experts felt that the Germans could have dealt a decisive blow on the western front if they had made the necessary deployments.”) Far along in their preparations to deploy and defend against gas, the Allies rapidly adapted. Within months both sides were using it, especially to deny mobility to the other side. Thus “poison gas, which was supposed to bring an end to trench warfare,… became the strongest factor in promoting the stasis of the war,” and intensifying its horror.34

“Sturmtruppe geht unter Gas vor” (Shock Troops Advance under Gas) by Otto Dix

What finally broke the barrier was the tank used in combination with artillery and infantry. “The turning point of the war,” according to a postwar German government commission, was the emergence from out of an early morning mist of French tanks counterattacking the German lines at Soisson on July 18, 1918—tanks that rolled over obstacles vital to the defenders’ sense of security.* “Tank fright” ramified. It colored what General Ludendorff called “the black day of the German army,” the August 8 attack at Amiens of four hundred British tanks (and eight hundred planes) that punched an eight-mile bulge in the German lines. The British took eighteen thousand prisoners, batches at a time surrendering to single tanks. And whereas eight thousand Germans were killed on August 8, the tank-accompanied British troops, attacking in the open, recorded half that number of fatalities over four days. By neutralizing the machine gun, the armored tank lifted the “storm of steel” fatal to attacking infantry.35

Ten Australian and Canadian divisions crossed no-man’s-land with those tanks at Amiens. Leaving the protection of the trenches, the men went “over the top.” Henri Barbusse evoked that moment: “Each one knows that he will be presenting his head, his chest, his belly, the whole of his body, naked, to the rifles that are already fixed, the shells, the heaps of ready-prepared grenades and, above all, the methodical, almost infallible machine-gun—to everything that is waiting in silence out there—before he finds the other soldiers that he must kill.”36

The Germans collapsed at Soissons and Amiens because they had lost one million irreplaceable men who had gone over the top in their last-ditch “peace offensives” between March and July. The nearly four years since the Battle of Flanders had proved the axiom that he who attacked lost heavily in men whatever few yards he gained in territory. On the relative safety of the trenches, consider the contrast between the casualties suffered by the German army in February 1918, when it stood on the defensive, and in March, when it attacked. Manning the trenches in February found 1,705 soldiers killed, 1,147 missing, and 30,381 wounded. Attacking in March the figures were 31,000 killed, 19,680 wounded, 180,898 missing.37

Amiens showed how far tanks could shift the odds to the attacker. However, while the tank could break into the German lines, with its vulnerability to shells, liability to breakdown, and short range it could not break through them. Of the 414 tanks in the August 8 attack at Amiens, just 38 were usable on the 11th and only 6 on the 12th. As the supple of tanks ran down in September and October the British high command reverted to the high-casualty infantry-artillery assault. Thus when the British “Tommy” took the offensive in the fall of 1918 he had grim occasion to look back on the “victory of the spade” as a victory for life over death.38

In licensing the spade, the generals licensed survival, a biological imperative that sapped the appetite for aggression. The trenches spawned a live-and-let-live solidarity between enemies sharing the same mud, enduring the same privations, and resenting in equal measure the same callousness toward their sufferings found at headquarters, in rear billets, on the home front, and in the patriotic press—a solidarity feared by the brass on both sides, who, sensing in it the makings of a politics of life stronger than nationalism, strove to break it.

On Christmas Eve 1914, Christmas, and New Year’s Day, soldiers from the opposing armies fraternized in no-man’s-land, primarily in the thirty-mile British sector but also in scattered places along the much longer length manned by the French. The Germans, sentimentalists over Christmas, took the initiative. CONCERT OVER HERE TONIGHT. ALL BRITISH TROOPS WELCOME, read a notice above a German trench. Football was played. Boxing matches proposed: He’ll fight anybody but an Irishman, some Germans shouted about their champion. Gifts were exchanged, along with information about the war, not all of it welcome. Captain J. R. Somers-Smith, of the London Brigade, claimed that a German asked him “in all seriousness”—“By how many Germans was London taken?” The high command took a hard line against this “unauthorized intercourse with the enemy” and aside from scattered manifestations it was not repeated.39

YOU NO FIGHT, WE NO FIGHT. This German sign captured one aspect of the truce that outlasted Christmas, an example of the live-and-let-live system that evolved from the need to survive. The average width of no-man’s-land was 250 to 300 yards, well within mortar range. But some stretches were much closer. In the section held by the Fourteenth British Division, the British and German trenches ran through the ruins of the same school. “In consequence, nobody thinks of throwing grenades about—a case of ‘those who live in glass houses,’ ” a British officer wrote. At Blangy the trenches were six feet apart. Violence in such close quarters was suicidal. So violence was curbed. Neither side could eat if shelling went on at meal times. So shelling was curtailed then. Burial details were often spared. Patrols in no-man’s-land stayed in their lanes, nodding as they passed.40

Live and let live lasted until late 1915, when Sir Douglas Haig replaced Sir John French as commander in chief of the BEF. Because live and let live cut against Haig’s policy of “ceaseless attrition,” he set out to destroy it with trench raids and mining. Introduced by an elite Canadian unit, the trench raid was a devilish innovation. A heavily armed party of raiders seized a section of German trench; then “retreated quickly so that support troops on the German side were caught in artillery fire.”41

“Trench Fight” by Frederick Horsman Varley

The attrition was mutual, the Germans responding in kind. Exploiting the memory of the Christmas truce, in one instance they used music as a ruse. “At six minutes to midnight [the band] opened with ‘Die Wacht Am Rhein,’ ” a German officer wrote home. “It continued with ‘God Save the King’… Then as the last note sounded, every bomber in the battalion, having been previously positioned on the fire-step, and the grenade-firing rifles, trench mortars and bomb-throwing machine, all having registered during the day, let fly simultaneously into the trench; and as this happened the enemy, who had very readily swallowed the bait, were clapping hands and loudly shouting ‘encore.’ ”

Doubtless that was not the end of it. Over three days one furious British brigade, enacting an epic “hate,” as the men termed spasms of retributive violence, flung thirty-six thousand grenades at the German trenches opposite.42

Too much can be made of live and let live. For one thing, it coexisted with sniping; and, as soldiers’ letters attest, with prisoner killing. And the attrition of everyday life in the trenches (an average of nine hundred Frenchmen and thirteen hundred Germans died every day of the war) generated an appetite for vengeance. “The Third Reich comes from the trenches,” said Rudolph Hess, Hitler’s deputy.43

“You seek to do justice to the Germans,” Clemenceau told Woodrow Wilson during the Versailles Peace Conference. “Don’t think they’ll ever forgive us: all they will do is seek an opportunity to take revenge.” For their part, Clemenceau, Wilson, and Lloyd George answered to publics that regarding Germany were not prepared to live and let live. Promised during the war that “Germany will pay!” they meant to collect in the peace.44

The infernal cycle of revenge. In the forest of Compiègne on November 11, 1918, Marshal Ferdinand Foch (second from right) and other Allied officers after receiving the German surrender inside the railway carriage; Hitler and generals waiting for the French generals to surrender at the same place in the same car on June 22, 1940.

H. G. Wells’s 1917 novel Mr. Britling Sees It Through conveys the climate of hatred seeded by the slaughter of sons. “Some one must pay me,” declares Letty Britling, pay for the death of her Teddy:

I shall wait for six months after the war, dear, and then I shall go off to Germany … And I will murder some German … It ought to be easy to kill some of the children of the Crown Prince … I shall prefer German children. I shall sacrifice them to Teddy … Murder is such a little gentle punishment for the crime of war … It would be hardly more than a reproach for what has happened. Falling like snow. Death after death. Flake by flake. This prince. That statesman … That is what I am going to do.45

At a ceremony marking the sixty-fifth anniversary of the D-Day landings in Normandy, French president Nicolas Sarkozy spoke of “the infernal cycle of vengeance” that had doomed Europe to centuries of war. The journey of a railway car tracks the twentieth-century cycle. The 1918 Armistice was signed in a wagon-lit in a clearing in a forest at Rethondes. In June 1940, German engineers freed the wagon-lit from the museum to which it had been annexed and returned it to the clearing. When, on June 22, the French generals arrived to sign the armistice with Adolf Hitler that ended hostilities between France and Germany, they found it covered by a Nazi flag. “The cycle of revenge could not be more complete.” But it had one more turn yet. Spirited to Berlin, the wagon-lit was “destroyed in an RAF raid.”46