“If you removed all the homosexuals and homosexual Influence from what Is generally regarded as American culture, you are

pretty much left with Let’s Make a Deal.”

“If you removed all the homosexuals and homosexual Influence from what Is generally regarded as American culture, you are

pretty much left with Let’s Make a Deal.”

FRAN LEBOWITZ

Like our nongay counterparts, most gay men and lesbians find themselves engaged daily on the material plain: We have to work, pay the rent, and buy groceries; we have to plan and budget our money and our time; and we have to think about the future. But unlike our straight counterparts, we also have to deal with homophobia. Not all homophobia is blatant gay-bashing; much of it is subtle. Perhaps homophobia is too strong a word. But no matter how out one is, there is always the extra awareness of being “different” that travels with us in the material world.

For many gay people, this difference is most apparent at work, especially for those who are not self-employed. What do you say when a colleague asks what you did over the weekend? If your co-workers display pictures of their spouses, should you? When the company provides benefits for workers and their spouses, does this include you? If it doesn’t, should you say something? Whom do you bring to the company picnic? No one? If you didn’t get that promotion you were expecting, was it because of your sexuality?

While no federal law yet protects gay men and lesbians from employment discrimination, gay people at many companies have worked together with management for institutional protection against discrimination and equal benefits for domestic partners.

Some gay men (and women) have access to money. But many more gay people don’t have those resources. Many of us stay in jobs that are comfortable, even if advancement opportunities aren’t available. Many gay people choose to live in “gay meccas” like San Francisco and New York, not because the best paying jobs are always there, but because they want to live someplace where there is a large and active gay community.

Community is important to most of us. As gay men and lesbians have learned over the last many years of the AIDS epidemic, we have to provide the financial support necessary to sustain the groups and organizations that in turn support all of us. As a community, we are learning to give, of our time and our money, so that we can continue to grow, in our hearts and in the material world as well.

From the moment we become aware of our homosexual desires and choose to act on them, we enter into a social arena that involves the use of our economic resources and that will also have an effect on our economic welfare. Going to a bar, we spend money on transportation and on drinks. Perhaps we may even buy clothes to wear at the bar. Even if we only cruise a park or a softball field we spend some money and time to get there. If we meet someone at one of these places and move in with them, it has economic results—we may save money on rent, and spend it on furniture.

Economics as a social science is devoted to understanding the individual’s participation in the economy as a consumer, as an employee, and as the owner of resources. It also studies the behavior of larger economic entities, such as corporations, nonprofit institutions, markets, and governments. It organizes these studies around the problem of how economic resources are allocated to various activities—production, consumption, and leisure.

Homo/economics is a new field of economic analysis that studies the economic behavior of lesbians and gay men. It also examines the impact of other people’s decisions on the economic welfare of lesbians and gay men.

Since the closet is still a significant factor in lesbian and gay life, it is impossible to measure the size of the lesbian or gay community or to estimate accurately either its income or expenditures. National polling organizations, survey research centers, marketing firms, and the U.S. Bureau of the Census are just beginning to collect the economic and demographic information we need to know in order to understand the economics of lesbian and gay life.

The social stigma against homosexuality has tremendous effects on the lives of lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals—its psychological devastation is now widely recognized, and socially the stigma has been a major obstacle to our pursuit of happiness, but the stigma also has had “economic” consequences that have imposed unfair burdens on the welfare of most homosexuals. The economic repercussions of the social stigma are different in different historical periods, or in different communities, or in different geographical regions, or for different characteristics like age, gender, physical traits or abilities, class, and race.

“If you removed all the homosexuals and homosexual Influence from what Is generally regarded as American culture, you are

pretty much left with Let’s Make a Deal.”

“If you removed all the homosexuals and homosexual Influence from what Is generally regarded as American culture, you are

pretty much left with Let’s Make a Deal.”

FRAN LEBOWITZ

Costly criminal acts. Laws against homosexual behavior still exist in twenty states in the U.S. and in many countries throughout the world. As long as those laws are enforced they not only impose severe psychological and social burdens on bisexuals, gay men, and lesbians, but also economic ones. In the 1950s, police raids of bars, tearooms, and parks not only led to arrest, legal fees, and public humiliation, but also to blackmail, the loss of jobs, and physical harm.

The high cost of double lives. Before Stonewall, living in the closet meant living a double life. Two worlds—one in which you dressed up to go to work, pretended that you dated the opposite sex and that you were planning to get married—and another world where you hatched or camped it up, slipped off to the nearest gay bar, a world where people knew you only by your first name, perhaps even a false name, and no one knew where you worked. No one really knew what you did on weekends. Being in the closet was the only was of controlling the information that you were queer. It meant that you lived under a lot of stress. You lied to your family and straight friends. You didn’t take your lover to the company Christmas party and people thought you were weird. Your boss was reluctant to promote you if you weren’t married. The was to manage your double life was to scale hack your career ambitions, segregate your social life, and live a lie that created emotional stress. Your therapy bills were huge just trying to deal with it all.

After Stonewall, the economics of the closet changed. Outside the major urban areas that had large gay populations, most homosexuals continued to lead double lives in the workplace. But it has become easier to have a social life that is somewhat more open as well as one that creates less stress.

Fear of firing. Before the growth of the lesbian and gay liberation movements, economic discrimination took the form of discouraging any closeted person from coming out. If you were arrested for some homosexual-related activity, you probably would be fired from your job or kicked out of your apartment.

The closet ceiling. Even if you stayed carefully in the closet, you might have missed cultivating important contacts in your work (so as to reduce the chances of anyone guessing that you were queer) that would have helped you get ahead. Or you might have chosen to go into a career that allowed you to express yourself more “explicitly” and where you might have found other lesbians or gay men, like becoming a male nurse, a female auto mechanic, a librarian, or a girl’s gym teacher. In a survey carried out by James Woods, the author of The Corporate Closet, among readers of OUT/LOOK magazine, he found that 46 percent of those questioned said that their sexual orientation influenced their choice of career.

Worth less? If you were a woman and/or African American you were more likely to be discriminated against for being female and/or Black than for being homosexual. Economist Lee Badgett found that despite the widespread belief that gay men (especially) and lesbians had higher than average incomes, in fact by some measures they earned almost a third less than anyone else from the same social background, the same occupation, or with the same education. And if you decided not to get married, the older you got and the longer you remained single, the more likely you were to earn less than your married counterpart.

Don’t ask, don’t tell. Nowadays job discrimination (as well as other forms of economic discrimination) continues to exist, but it operates a little differently. It can take a bigger toll if you are out than if you are in the closet. It also is more likely to affect you if you don’t conform to gender norms. One national survey in 1987 reported that one out of four Americans “strongly objects” to working with lesbians or gay men on the job—and another 27 percent said that they “would prefer not to.” And Mark Fefer, writing in Fortune magazine, found that two-thirds of lesbian and gay employees had seen some form of overt homophobia in the workplace.

(Donelan)

You’re not in Kansas anymore. Probably the most significant economic process that underlies the growth of lesbian and gay communities is the migration of homosexuals away from the suburbs, towns, and small cities that they grow up in to the anonymity of large and cosmopolitan cities—New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, and New Orleans have historically served as magnets for both closeted and open lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Overlooked Opinions, the gay marketing research firm, claims (although it is probably an overestimate) that 45 percent of lesbians and 53 percent of gay men live in urban areas, and that 32 percent of both lesbians and gay men live in the suburbs, which suggests that approximately 23 percent of lesbians and 15 percent of gay men live in rural areas.

We’re here, we’re queer, we’re setting up house. Once some young lesbian or gay man got to the city, they often found housing in neighborhoods that housed other queer folk, such as bohemians, prostitutes, and new immigrants. That is why New York’s Greenwich Village, San Francisco’s North Beach, and New Orleans’s French Quarter became the first gay neighborhoods after World War II. Later, other neighborhoods attracted lesbians and gay men with low rents and tolerant neighbors. As in other aspects of gay life, race and gender have a decisive effect on the residential patterns of homosexuals. By preference and in reaction to racism among white homosexuals, African American, Latino, and Asian American lesbians and gay men often live in neighborhoods traditionally inhabited by their ethnic and racial communities. Lesbians and gay men’s economic differences also lead women to live in neighborhoods with lower rents.

Business comes out of the closet. If the most successful businesses serving the gay and lesbian populations before Stonewall were bars and mail-order businesses, then the growth of gay liberation spurred whole new developments—bookstores, counseling services, porn shops, newspapers and magazines, clothing boutiques, and travel agencies have emerged to satisfy gay and lesbian consumer needs that previously had not been targeted by any other businesses. Gay and lesbian businesses serve a growing and increasingly diverse population. There are now businesses that cater to the needs and interests of African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans, as well as bisexuals and leather folk of all identities.

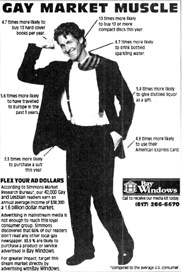

The gay market boom. While the growth of lesbian and gay businesses means that more queer dollars are spent within the lesbian and gay communities than used to be the case, most queer dollars still end up in the coffers of “straight” businesses. In the last ten years, “straight” American corporations have discovered that lesbians and gay men love to shop—and they are spending more money than ever before marketing their products to queer consumers. Although studies by marketing research firms tend to overestimate the financial status of the average lesbian or gay men, their surveys do tap into lucrative market segments of the gay community. According to data from Overlooked Opinions, the average household income for lesbians in 1992 was $45,827, while for gay men it was $51.325—as a comparison, the 1990 average household income in the U.S. was $36.520. One newsletter, Affluent Marketers Alert, estimates that gay men spend two out of’ every three queer dollars. Other examples of the lifestyles of lesbians and gay men are indicated by the fact that more than 80 percent of gay men dine out more than five times in any month. Forty-three percent of lesbian own their homes, as do 48 percent of gay men. Together, lesbians and gay men took more than 162 million trips in 1991. Writing in Dollars and Sense magazine, Amy Gluckman and Betsey Reed have concluded that the gay marketing movement obscures the economic disparities caused by racial differences, social class, and gender that plague the gay community. Unfortunately, as Gluckman and Reed point out, the gay marketing bonanza has encouraged corporations to cultivate a narrow definition of gay identity (white, male, affluent) as a marketing tool.

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

Since gay and lesbian bars catered to people who were stigmatized or who engaged in “criminal acts,” before the 1970s the owners of the bars in most American cities were forced to pay the police or organized crime for “protection.” This made drinks more expensive, because the bar owners sought to recover the costs of “protection” by charging higher prices. Patrons had no recourse; there weren’t that many other places you could take your business if you weren’t happy with the decor, the price of drinks, or the clientele.

The family has become less and less an economic institution and more and more a place for the rearing and socialization of children. Legally recognized marriages and families are still a heterosexual Preserve.

Domestic partners. There is, however, a strong and growing movement among lesbians and gay men for the legalization of gay marriages. Legislation for the recognition of domestic partnerships is a step in the direction of socially acknowledging the importance of homosexual relationships. Legally recognized marriages do have definite economic advantages in the form of tax breaks, health insurance coverage, and credit availability. Lesbians and gay men, whether or not they have children, do pay school taxes and their tax dollars help to support governmental social services for families and children.

A queer baby boom. Before Stonewall, of course, many lesbians and gay men were parents. Lesbians and gay men had married before they became aware of their homosexual desires, or specifically in order to raise families, as well as for the convenience of appearing straight in a hostile world. But not many of them raised children as openly gay or lesbian Parents. Scientific and social innovations have made it easier and easier for a woman to get pregnant without necessarily engaging in heterosexual intercourse. Lesbians have taken advantage of developments such as artificial insemination in order to bear children and set up families with their partners or in conjunction with their (often gay) male friends. In the last ten years, this way of having and raising children has grown tremendously. Today there are more than 10,000 children (according to Newsweek) being raised by lesbians who became pregnant through artificial insemination. Adoption is another important means allowing gay parents to raise children. Complicated arrangements between lovers, ex-lovers, and male friends have created new kinds of families for raising children. The economic implications of forming a queer family and raising children are quite similar to those faced by heterosexual families. The decision to raise children will often depend on the financial resources of the parents, their sense of job security their health insurance coverage, and the availability of child care and schools. But added considerations originate in the effect of homophobia on their ability as lesbian and gay parents to provide a financially secure and stable home for their children.

“Gee, Dad, you shiuldn’t have.” (Donelan)

Divorce bells are ringing. Breaking up is hard to do, but when those doleful divorce bells start tolling you know it will cost both of you money. Although alimony and fees for divorce lawyers are not yet common among lesbian and gay couples, they are not far off. When a couple breaks up, one partner often has to mime out of their joint home, and furniture, kitchen utensils, books, and CDs have to he divided up. Most times, each partner has to bear some additional cost—looking for a new apartment or a roommate, replacing household items and other joint purchases. Where children are involved, legal negotiations are part of the process—custody, visiting rights, and financial support are often hotly contested issues.

Economists often identify investments in education, migration, health care, and experience as human capital. Certainly to the extent that lesbians and gay men invest in their skills and other attributes in order to improve their economic welfare, they have invested in human capital. Discrimination, illness and death from HIV, and the limitations imposed by living inside the closet all destroy human capital.

The queering of American culture. The gay contribution to American culture is enormous—and seems to be increasing. A great deal of this queer contribution originates in the lessons that lesbians and gay men learn as outsiders, sexual rebels, and the task of inventing new ways of living their lives.

The AIDS epidemic is now in its fourteenth year. In addition to the many lives it has taken, and the grief that it has spread in its wake, it has imposed a huge economic burden on the gay and lesbian communities, as well as society as a whole.

The stigma of AIDS. People with AIDS are still stigmatized in some communities and suffer discrimination in housing, employment, and health care. People of color who have AIDS experience an even greater degree of discrimination than white men with HIV. Lesbians and gay men who are IV drug users also encounter discrimination. All together, these forms of discrimination and stigmatization reduce the economic welfare of the gay men and lesbians with AIDS.

Jobs and health care. Individuals who have developed more advanced HIV-related illnesses have often lost income through the loss of full-time jobs, and even if they are able to continue working must sometimes take jobs that pay less or work fewer hours. These individuals also experience increased costs for medical care. Since most Americans receive their health insurance through their employers, marry of those who have such medical coverage want to hold on to their jobs. They may often be afraid to let their employers and fellow employees know if they have AIDS—they preserve their ability to meet the medical costs of HIV, but often suffer isolation and lack of emotional support.

“The Idea that open gays hit a ‘lavender ceiling’ is probably the biggest reason professional gays cling to the closet.”

“The Idea that open gays hit a ‘lavender ceiling’ is probably the biggest reason professional gays cling to the closet.”

CAROL NESS IN “CORPORATE CLOSET,” SAN FRANCISCO EXAMINER, OCTOSER 10, 1993

The economic impact on the community. The AlDS epidemic has drained economic resources from the gay and lesbian communities. The mobilization of the gay and lesbian communities to provide support for people with AIDS and the creation of institutions for education, care, and research about AIDS has diverted resources from other more traditional activities like education, leisure activities, investment in small businesses and careers, and improving real estate. In the last five years, probably the largest economic institutions in many gay communities have been AIDS nonprofit organizations.

Market and community. The recent discovery of a lucrative gay and lesbian market for consumer goods has provoked many reactions. Some people believe that the growth of such a market reflects an acceptance of lesbians and gay men by the broader society. Others believe that the existence of a big gay market will undermine the community that lesbians and gay men have so carefully constructed since the fifties. In truth, the existence of such a market does reflect our visibility, while at the same time creating an opportunity for non-gay-owned businesses to make money from lesbians and gay men. The tension between community and market is not new, nor is it easily resolved. The economy of the gay and lesbian community remains an arena for research and struggle over the next decade.

—JEFFREY ESCOFFIER

Lesbians and gay men are in all walks of life. We are carpenters and computer programmers, hairstylists and bookstore owners, sales reps and schoolteachers. We are self-employed and underemployed (some of us are even unemployed). But what we all share in the workplace, whether we work in a corporation or for a nonprofit firm, is the dilemma about whether or not to be out at work. Even in jobs we love, we are sometimes uncomfortable. While the decision of whether or not to be out is a personal one, the implications are public. We share, too, the struggle to be seen as equal to our nongay colleagues; the saying that a woman has to work twice as hard as a man to be seen as half as competent can be applied to gay people on the job as well.

FIVE BEST COMPANIES FOR GAY MEN AND LESBIANS

Based on employment policies, benefits, outreach, and general attitude (shown alphabetically):

Apple Computer Company (Cupertino, CA)

Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae)(Washington, D.C.)

Levi Strauss & Company (San Francisco, CA)

Silicon Graphics (Mountain View, CA)

Viacom International Inc. (New York, NY)

—ED MICKEMS

On the other hand, many corporations, small companies, and labor unions do recognize that they have gay employees who deserve all of the rights and benefits that they provide to their straight employees. Indeed, many companies are way ahead of the laws when it comes to protecting their gay and lesbian employees. Often, we are organizing to make these changes happen. Ten years ago, there were no officially sanctioned gay and lesbian employee organizations in corporate America; today, most large companies have such groups.

In the 1990s, more and more people are going into business for themselves, and gay people are no exception. The reasons, however, are not always the same. The independence of self-employment is an added boon for gay people. Some want to earn their livelihood serving their own community. For some “obvious” gay men and lesbians, self-employment is one of the few avenues available to earn a living free of harassment; for others, being able to set a queer tone at the office is the appeal. But for whatever reasons, statistics show that lesbians and gay men are more likely to be self-employed than are the population at large.

“Come on! Hair and makeup! The top people who do hair are men, and the top people who do makeup are men! And each and every

one of them Is gay!”

“Come on! Hair and makeup! The top people who do hair are men, and the top people who do makeup are men! And each and every

one of them Is gay!”

KEVYN AUCOIN, GAY NEW YORK MAKEUP ARTIST, IN THE WASHINGTON POST, APRIL 25, 1993.

I’ve come out on the job in a big way: I became spokesperson for my company’s lesbian and gay employee group. Now everybody knows. My gay colleagues say I’ve just committed career suicide, but I like my job, I do it well, and expected to go far in this company. Now I worry, Are they right?

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

A 1992 survey of 1,400 gay men and lesbians in philadelphia found that 76 percent of men and 81percent of women conceal their orientation at work.

This question sums up one of the biggest fears among upwardly mobile, career-minded gay men and lesbians. A company may be unlikely today to fire someone for sexual orientation, but that doesn’t mean you’ll get the subtle mix of credit, promotions, training, and mentoring that leads to a successful career.

The question is so important, I opened it up to a panel—and their audience—at the first National Gay and Lesbian Business Exposition held in April 1994 in New Jersey. The consensus? We just don’t know yet.

The “glass ceiling” is a proven phenomenon among women, people of color, and other minorities, because we can actually count heads in middle management, upper management, boards of directors, etc., and see that they are underrepresented the further up you look in the corporate hierarchy. That doesn’t work for gay people, obviously, first because we’re impossible to count (and there’s still the difference between those who are out and those who choose to follow a “don’t ask, don’t tell” approach with their employers); secondly, because we include women, people of color, and other minorities within our own numbers, and there’s certain to be a complex overlap and interaction among prejudices.

A welder in the San Francisc Bay Area. (Cathy Cade)

Chicago-based career counselor Judi Lansky takes a cautious approach advising lesbian and gay clients on this issue, pointing out that there are many companies and whole industries where simply being unmarried is a career liability. A life-partner of the same gender would he beyond comprehension.

Lee Badgett, a labor economist and assistant professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Affairs, did a recent study that matched gay and straight full-time workers by many characteristics (gender race, location, education, experience, etc.) to gauge the economic impact of antigay discrimination. Among many interesting conclusions, she found that lesbians were more likely to enter lower-paying jobs than other women, and didn’t seem to experience any significant pay discrimination. Gay men, on the other hand, were more likely to go for higher-paying jobs than nongay men and tended to earn 11 to 27 percent less than their nongay peers. Badgett’s data, however, did not include any information on who was out or not.

“We believe that diversity isn’t something that you should tolerate. It’s something you should promote.”

“We believe that diversity isn’t something that you should tolerate. It’s something you should promote.”

HARLAN LANE, PROFESSOR OF PSYCHOLOGY AT NORTHEASTERN, ON WHY THE CAMPUS HAS PROMISED TO ACTIVELY RECRUIT AND PROMOTE OPENLY GAY AND LESBIAN EMPLOYEES

Many gay and lesbian managers who have come out, brought partner to company events, and otherwise integrated their personal and professional lives, say their careers haven’t been harmed, and have even been enhanced. They observe that a glass ceiling can work in two ways: imposed by supervisors through prejudice, and self-imposed through the peculiar behavior of, trying to coyer up your personal life. The higher up the corporate ladder you go, the more important personal chemistry is. And if you’re hiding something, it gets noticed.

Some of these out managers have already received promotions. But being out on the job is still a relatively new phenomenon, and unfortunately limited mostly to younger (I’ll include up to the forties here, thank you) people still in lower and middle ranks. So we’ll have to see how their careers progress over the years.

We aren’t going to be short on case studies. A new study by Jay Lucas (co-author of The Corporate Closet) and Joe Stokes, professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, says that a large majority of gay men and lesbians have had a good reception to their coming out at work, and most saw no negative impact on their careers. Most planned to be “more out” in the future.

—ED MICKENS, FROM THE SYNDICATED “WORKING IT OUT” COLUMN

We are here to make a statement for the people who met last night at the lesbian/gay caucus. First, we would like to invite any other gay brothers or lesbian sisters out there who would like to do so to please stand up. Now if all the lesbians and gays here stood up, it would he the equivalent of ten tables, as at least 10 percent of the population is gay or lesbian.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

In 1991, Lotus Development Corporation, creator of Lotus spreadsheet software, became the first major publicly held American company to extend benefits to the domestic partners of lesbian and gay employees. Four months earlier, a similar policy was adopted by Montefiore Medical Center, a privately held company in New York (with 9,500 employees, three times as many workers as Lotus). Levi Strauss & Company followed in February 1992, becoming the largest U.S. employer, with 23,000 workers and sixty facilities nationwide, to offer health insurance to lesbian and gay domestic partners. In the years since, a number of large and highly visible companies have undertaken similar changes in their business practices.

The fact that so few people stood up shows how pervasive homophobia and discrimination against lesbians and gays is in our society. It just doesn’t feel safe to come out even at a progressive conference such as Labor Notes. To be publicly identified as gay could cost us our jobs, our children, or our lives.

Even within our unions we are faced with ostracism, ridicule, and marginalization. We are everywhere. We are in health care, the building trades and the Teamsters, textile mills, and schools. We are all races and cultures and all countries.

We are making this statement to you because we believe that people who come to the Labor Notes Conference are people who really understand the truth of labor’s slogan that “An injury to one is an injury to all.” People who are involved in fighting for the rights not only of labor as a whole, but also of women workers, workers of color, workers in South Africa, Central America, or in the South. We all know that it is important to fight for all these labor movements, because the bosses capitalize on weaknesses within our ranks. Discrimination is used to divide and conquer workers.

When the union fails to defend the rights of gay and lesbian workers, the only winner is the Boss. When lesbian and gay families don’t get the same benefits that other families get, the Union that bargained and worked so hard is the loser.

We offer you a challenge. There are concrete things that you can do to support your lesbian and gay sisters and brothers.

—PRESENTED AT THE LABOR NOTES CONFERENCE 1991

It was Friday, June 24, 1994, “Stonewall 25” week-end. Roughly 250 lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgendered people gathered at AFSCME, District 37 headquarters, the big public employees union in New York. Hosted by the official lesbian and gay committee of the union, they came together from all over the country to found a national organization. The National Lesbian/Gay/Bi/ Transgendered Labor Organization (NIGBTLO) became the first labor organization of its kind in the United States.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

When studying the impacts of providing health care benefits to partners of homosexual employees, Lotus Development cited findings from a private insurance study that say committed homosexual couples are at no greater risk of catastrophic illness than are married heterosexual pairs. Moreover, with few children in gay families, there are few claims for, say, cesarean sections or routine pediatric illnesses. So much for claims by opponents of astronomic health care costs due to AIDS.

Some joined because union lesbians and gay men are at the cutting edge in the struggle to win equality on the job. Some joined because a relative political shift to the right by the mainstream lesbian and gay movement has encouraged the growth of anti-working-class and antiunion tendencies in lesbian and gay politics, including among self-described “progressives.” This has left lesbian and gay working people feeling voiceless and frustrated. NLGBTLO strengthens the voice of working-class lesbians and gay men within our community, helping to bring class and union politics back into the lesbian and gay movement. Still others had come simply to break out of isolation and unite with other pro-union lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgendered people.

In the nation’s capital, the lesbian/Gay Labor alliance marched with others against American involvement in Central America in 1984. (©JER)

While gay people have always participated in the labor movement, it was in the mid-1970s that we began to openly and boldly assert ourselves within the unions. In 1976, a crowded press conference featuring lesbian and gay activists and union leaders from more than twenty local labor unions pledged the support of the San Francisco Labor Council for gay rights in all future union contracts. As a result, 1977 demonstrated strong union opposition to the antigay Briggs Initiative, and lesbian and gay support for the Coors Beer Boycott.

Some of the activists who spearheaded these struggles on the West Coast later became the Lesbian/Gay Labor Alliance (L/GLA) in the San Francisco Bay Area. The L/GLA, together with the Gay and Lesbian Labor Activist Network (GALLAN) in Boston, the Lesbian and Gay Labor Network (LGLN) in New York, and the Lesbian and Gay Issues Committee (LAGIC) of AFSCME District 35, was the driving force behind the creation of a national labor organization for lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgendered people.

Lesbian and gay unionists continue to gain a hearing within the U.S. labor movement. Nondiscrimination clauses, protection and services for people with AIDS, and domestic partnership benefits are among the rights many unions are fighting to achieve for their lesbian and gay members.

—ED HUNT

SUGGESTIONS FOR MAKING YOUR UNION SAFER FOR ITS LESBIAN AND GAY MEMBERS

• Participate in your city’s gay pride march.

• Confront co-workers when they make anti-gay jokes.

• Include gay and lesbian issues in your local civil rights committee.

• Talk to lesbian and gay co-workers and find out what issues they think the union should take up.

• Wear a gay or lesbian button to work, just for a day, and see how people react to you.

• Start up or participate in a committee to gain domestic partner rights in your union.

• Participate in AIDS education programs.

• Support getting Lavender Lahor, the newly formed International Network of Lesbian and Gay Labor Activists, which already has members from three countries, onto a plenary at the next Labor Notes Conference.

• Help distribute the Lavender Labor Newsletter.

Gay and lesbian employees at many companies have formed official and unofficial gay networks. Here is just a sampling of groups. If your company doesn’t have one, you might consider starting one informally and see where it leads.

Apple Computer: Apple Lambda

AT&T: LEAGUE (Lesbian and Gay United Employees)

Chevron: CLAGE (Chevron CoreStates Bank: Mosaic Lesbian and Gay Employees)

Coors Brewing: LAGER (Lesbian and Gay Employee Resource)

Corestates Bank: Mosaic

Digital Equipment Corp.: DECplus (Digital Equipment Corp. people like us) and WICS (Women in Comfortable Shoes)

Dupont: BGLAD (Bisexual Gays and Lesbians at Dupont)

KQED TV: GALS (Gays and Lesbians)

Microsoft: GLEAM (Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Employees at Microsoft)

Kodak: Kodak Lambda

3M Corp.: 3MPLUS (3M people like us)

TimeWarner: LGTW (Lesbians and Gays at Time Warner)

City of Seattle: SEAGL (Seattle Employee Association of Gays and Lesbians)

Silicon Graphics: Lavender Vision

United Airlines: GLUE (Gay/Lesbian United Employees)

U.S. Government: FedGLOBE (Federal Gay and Lesbian or Bisexual Employees)

U.S. West: EAGLE (Employee Association of Gays and Lesbians)

Xerox: GALAXY (Gay and Lesbian at Xerox)

— ED MICKENS

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

The group Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Employees at Microsoft (GLEAM) became the first gay employees group in the country. They received formal recognition from the company in 1991.

Many lesbians and gay men face the question of whether or not to be out when applying for a new job. One gay librarian posted her dilemma on the gay and lesbian librarians bulletin board. Following is her dilemma and some of the responses.

I have a job interview coming up in a couple of weeks, and I am getting very nervous. On the second page of my resume I put my involvement as co-chair of the board of directors and librarian for the local Gay and Lesbian Resource Center under “Community Service Activities.” This isn’t the same as saying “1’m a lesbian, y’all,” but it’s relatively close. Well, back then I didn’t feel like I had anything to lose, but now I’m starting to want this position badly. I can feel my internalized homophobia rising—there’s this nasty voice in my head that’s telling me to hide, because people might not like me if they think I’m queer, and I won’t get the job if they don’t like me.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

There has been significant lesbian and gay political activity within several major labor organizations around the country for some time. Among these organizations are the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the Communications Workers of America (CWA), the United Auto workers (UAW), the Teamsters and the United Steel Workers of America.

Some background—I live in a small, conservative city in Iowa, and currently work for a college affiliated with the Catholic Church. I am out to many of my co-workers, but not to my boss or to the campus at large. I guess what I’m looking for from my fellow librarians is some words o’ wisdom from others who’ve been here before and found the courage to cross that line.

—A LIBRARIAN

• • • •

Does your sex life influence your work? Not usually. I have a very good job that I got just two months ago. I never said word one containing gay in it at the interview. I have a wedding band on, which means to me I’m married. But I’m married to another man. They didn’t ask, I didn’t tell. I personally don’t think that not telling is bad. Really, your employers have no right to ask about your personal life. I keep my job and my personal life separate. I feel that for safety’s sake, you should not tell, especially at the interview. They will hire you if they think you are the best person for the job. Your telling them could color their discussion. Heterosexuals don’t tell, “Oh I’m having sex with so and so” in an interview. I’ve never heard that. Why should we tell?

—A.

• • • •

I work in a technical library where, aside from an occasional AIDS book purchase recommendation, my sexual orientation is irrelevant—on paper. I happen to work mostly alongside of people with less education, less experience of human diversity, and less liberal religious views than I have. Once I started work here, I dropped a few hints and mentioned a few things to avoid being presumed straight. Behind my back some of my co-workers went to the head manager and apparently tried to get me fired or disciplined. She told them to stuff it, but they can persist in their views. (Over the years they have changed, somewhat, because I’m not the green scaly monster they assumed I was.)

There was no way to predict all this from the interview. Personally, I’d go for the discreet mention on the resume (if it’s relevant) and let them conjure up what they want in their own minds. You can always work to change attitudes if problems arise later.

—B.

• • • •

I agree that having something suitably clear on the resume is adequate. I keep my gay publications on my resume for just that reason. No one has ever asked me about them in an interview.

Frankly, I think there are major advantages to having the truth visible from the start. If some potential employer or co-workers are going to make a big issue of my being gay, I don’t want to work for/with them. I’d rather spare myself the hassle in advance. No matter how attractive the job itself might seem, that would he more than just a fly in the ointment. (And, taking it from another angle, they don’t DESERVE my efforts. I’ll put them where they will be appreciated properly.)

—G.

• • • •

If your involvement with community activities is already on your resume, believe me, it *has* been duly noted. Speaking from my own experience, on both sides of the table, it is one of the first things interviewers look for, right there under the proverbial “other.” If you’ve gotten this far in the process, then they know you can do the work. The salient question is how well you’ll fit into their group. If there is a point in the interview where it seems appropriate to mention your involvement in community activities, then by all means mention it, but don’t make an issue of it. Present it as part of the well-rounded professional everyone would want on their team; you are, after all, much more than a librarian or a lesbian.

—R.

• • • •

Because you’re not in a desperate situation, you can afford to be completely yourself at your interview. I personally wouldn’t want to work for an institution that didn’t like something about me. No job is the center of the universe and worth compromising your life for, IMO [in my opinion]. I find that being completely out is very freeing. My spirit soars a little higher than it once did. :)

—R

• • • •

I think there is an important question queers have to ask ourselves before we go into interviews: “Can I be happy working in an environment where I can’t be ‘out’?” If you can, don’t include your queer stuff in your resume and don’t he out at the interview.

IT’S GREAT TO BE GAY AT AT&T

PROVIDED BY THE LESBIAN. BISEXUAL & CAY UNITED EMPLOYEES AT AT&T LEAGUE

If you can’t, then be out at the interview. I always try to remember that I am interviewing the institution as much as it is interviewing me.

I have to differ with some of the opinions I have seen expressed about the relationship of our sexualities to our work and our workplace. I couldn’t disagree more with the notion that heterosexuals don’t tell us constantly whom they sleep with. Every family photo, mention of a husband, wife, child, every discussion of tax exemption or family tuition remission—in short, most of the daily chat of the workplace tells us that heterosexual men and women have sex.

—M.

The editors of this volume sent out a short survey to gay and lesbian workers regarding whether people were out at work, and if not, why not. We also asked for experiences, good and bad, regarding being out, as well as a subjective view of the ideal work environment. Responses came in from around the country, both on-line and in hard copy. The questions and some of the responses follow.

If you are out on the job, how does being gay or lesbian affect your relationship with co-workers and/or bosses?

It has improved personal relationships with my peers; there are people I work with that I consider friends. Being out was part of getting close. I don’t think it has been to my advantage for my boss to know, although I can’t prove it. I feel being out has held me back some. I’ve had to work harder than others for respect and recognition.

—VANESSA, MANAGER, SOFTWARE DEPARTMENT, CAMBRIDGE, MA

Surprisingly, some of the people who have been the most resentful of my being out and fighting against any bigotry have also been gay. When I began working for New York City, I had major problems with directors who could not deal with my being open. One told me that I was passed over for a title change because the person who got the position had a family. But as the gay rights movement grew, attitudes changed drastically. Now, because of my constant fighting against discrimination, I am feared by many. My attitude is that I would rather be feared than discriminated against. At the present time, though, sexual identity rarely comes into play with employee/boss relationships unless in a positive way.

—MAX, SUPERVISORICOMPLAINT MEDIATOR, NEW YORK

It varies—different individuals react more or less friendly, depending on where they are at. I feel safe because of many other openly gay people and an anti-discrimination policy.

—ANNETTE, AT&T CUSTOMER SERVICE REP, PROVIDENCE, RI

I am out at work and my co-workers and bosses have gotten used to it. Some don’t care, some do, I have not heard any anti-gay comments at work; they know to keep their mouths shut if they feel that way. Also, I am the shop steward and this affects the work environment a lot more for me. If my co-workers have a problem or get in trouble, it’s me they have to come to—the gay man.

—MARK, PARKING PATROL DEPUTY, PORTLAND, OR

When I applied for this job, it was clear on my resume and cover letter that I am gay, and I raised the issue in the job interview. I wanted us ALL to know what we were getting. When I started working here, lots of departments invited me to their staff meetings, ostensibly to talk about how we could work together, but REALLY to see what the gay guy from California was all about. That was OK with me. Now, after five years, it really isn’t much of an issue. They know that I will spend some of my time working on gay/lesbian issues, but they also know that I do a good job and won’t “cheat” them of hours.

—LAWRENCE, UNIVERSITY DIRECTOR OF CAREER SERVICES, MAINE

I work in a small department (five persons total, only two of us working at any given time) at the local public library. I was out to my main boss from the very beginning—came out on my application and in the interview. The others found out gradually as we got to know each other. I don’t think it affects our relationships in any negative way at all now that I am completely out. Before I was completely out, I felt a need to be rather discreet in my chatter until I realized that everyone there is okay about it. My main boss and I talk about gay things from time to time. My immediate supervisor has a similarly positive attitude toward LGBTetc persons, and we have discussed a number of different aspects of it. In all, I think it’s just like any other aspect of one’s personality among my boss and co-workers.

—TINA, PUBLIC LIBRARY CLERK/PAOE, KNOXVILLE, TN

I am completely “out” at work. I have my significant other’s picture on my desk and have been trying to get my company to institute domestic partner’s benefits. To be honest, it hasn’t hurt.

—JEFF, HUMAN INTERFACE SOFTWARE ENGINEER, SAN FRANCISCO

My team leader asked and I was honest. Our working relationship has improved although she is “straight and happily married.” We routinely discuss our marriage problems—and they are common. I also told her that it’s not a “secret” of mine so she can share it with whoever she wishes. Hasn’t been a problem, but most of us have a four-year college degree or higher and I think that makes a big difference.

—RICK, COMPUTER SPECIALIST, NORFOLK, VA

• • • •

I’m not out to some folks I consider to be big time, well-rounded bigots, don’t have the time to deal, what would I get out of it?

—VANESSA

For those that don’t know, it’s because they haven’t specifically asked. Perhaps they don’t want to know. I feel it’s their right. On the other hand, I don’t want them to think I’m drawing a focus to my relationship with my lover. That may be interpreted that I need special attention, which I don’t. I wonder how many gay people do it JUST for the added attention.

—RICK P.

• • • •

Feels like it’s the same thing I get for being female and Puerto Rican—you know, I get 59 cents for every $1 my straight, white male co-worker gets.

—VANESSA

One man just goes out of his way to ignore me and avoid any contact whatsoever.

—CAL

Being transferred to another division after I complained to one director about comments/actions directed at me as a gay male. The director told me to stop complaining, then transferred me.

—MAX

I was fired from a previous fob.

—ANNETTE

I was removed from my position as a board member of my union and strongly lobbied against for being a delegate to that same union.

—GLEN, UNION ACTIVIST/CIVIL RIGHTS WORKER, BROOKLYN

When I first started here, I got a few (three, I think) phone calls on my voice mail fro a group of girls that were pretty vicious…in an adolescent way. A few years ago, someone shot paint pellets at my office window a few times. The campus police were great about investigating both.

—LAWRENCE

“Straight” thrill seekers are always wanting to experiment.

—EDWARD, COMPUTER NERD, UTAH

The straight boys don’t talk to me yens much.

—MARK

“Straight” thrill seekers are always wanting to experiment.

—EDWARD

The straight boys don’t talk to inc very much.

—MARK

Helping teenagers that are confused by society’s rules figure out that it’s society’s problem and not theirs and to get on with their life—their happiness is their responsibility.

—BOB, MENTAL HEALTH WORKER, SAN FRANCISCO

Help “educate” some people who were “borderline bigots”—people who came to like me and then discover I am a lesbian.

—VANESSA

Being involved in the company’s and union equity committees.

—CAL

Being able to just be honest, not having to worry about being discovered.

—ANNETTE

More people come out to me and therefore we don’t feel so isolated.

—GLEN

I will never forget when I got back from the March on Washington, and one of my co-workers held up the newspaper with a shot of the MOW crowd and asked (jokingly), “So where are you in this picture?” It just gave me such a great feeling of acceptance.

—TINA W.

Entrepreneurship is one way gay men and lesbians can capitalize on our differences instead of hiding them at work. The world now seems to favor entrepreneurs with our experience and life training to master today’s markets. If our experiences are different in many ways, how can the challenges we’ve faced count as future assets after being labeled liabilities for so long? Our survival skills often match those required for entrepreneurship; we need to mobilize these differences, not deny them. Let’s look at some of the challenges, why they’ve often been handicaps in the past and how we can make them work to our benefit as entrepreneurs in the nineties.

“When it comes to setting trends, queers are always at the vanguard. And the computer revolution is no different.”

“When it comes to setting trends, queers are always at the vanguard. And the computer revolution is no different.”

TOM REILLY. A FOUNDER OF DIGITAL QUEERS. A GROUP OF COMPUTER INDUSTRY GAY MEN AND LESBIANS

1. Eliminating Isolation: Many closeted corporate gay people believe “personal factors have nothing to do with business.” Yet today’s emphasis on chemistry, networking, team playing, and heavy hours all push the personal into the professional. If we come out, we can network with a vengeance and position ourselves as valuable assets. In addition, we can sometimes operate outside the corporate caste system as corporate Merlins, consultants, and as entrepreneurs.

2. Handling Prejudice: When prejudice does show its ugly face, we need to show deep loyalties to those in whom we find tolerance, trust, acceptance, and understanding. This may be a boss, mentor, work group, employer, contact, supplier, or client. Such loyalty, rare in the nineties, is often handsomely repaid in business relationships.

3. Achieving Self-Containment: As the odd person out, perhaps we faced despair and discovered the freedom that comes from being written off. As a “society of one,” an unclaimed asset, we can quickly respond not only to other gay men and lesbians but to society’s “interesting” people: its movers, shakers, and leaders.

4. Taking Tax Advantage: The fact that our relationships are unrecognized and therefore defined as “arm’s length” by the IRS is advantageous tax-wise. We can employ each other, sell things to each other, and in other ways take advantage of the fact that we are in reality together but legally apart.

5. Sheer Necessity: If we have fewer children and double incomes, our higher discretionary incomes may mean simply higher taxes and lower deductions as salaried employees. That alone may be a necessary reason to start our own firms. It is no accident that the wealthy have three times as many entrepreneurs in their ranks as the salaried.

6. Breaking the Glass Ceiling: When we come out and raise issues, we sometimes become stereotyped and our potential for top management can get lost under a special-interest label. Often the choice is between fighting political battles and simply building careers. When this happens the way to the top may be from the outsideᾹfrom the top of our own organizations.

7. Recognizing Diversity: We are often a double or triple minority. If this translates into a desperate search for a home, we can easily get lost in a gay ghetto, nesting in a very specialized niche. But being gay and belonging to another minority can also be the best qualification to feel the pulse of America’s developing diversity. If we’ve developed years of multicultural skills and style flexibility, this may translate into entrepreneurial market awareness and a client orientation.

8. Defying Homophobia: AIDS activists have shown that we can channel our anger into action; we can act up and not just act out. Many of us have capitalized on the gay experience to excel in the creative professions and launch businesses to serve our own. Perhaps we are at the point now where many of us in fact would make better entrepreneurs than employees.

A common element to successfully transforming our experiences and differences as gay men and lesbians into assets, not handicaps, may be fully coming out, which may require a willingness to take work seriously. Coming out assumes a desire to make work meaningful, as well as a willingness to shoulder entrepreneurial responsibilities and opportunities.

—PER LARSON

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

After watching a parody of popular beer commercials on Saturday Night Live, the aptly named gay attorney Michael Beery decided to produce and market his own “Pink Triangle Beer” to the gay community. Brewed in Iowa, it was launched in a half-dozen U.S. cities in 1994. What will they think of next? (There’s no world yet on what happens when straight people drink it.)

1962: The Tavern Guild (San Francisco): A league of gay bar owners and employees that formed after a feud between city police and state alcoholic beverage control agents had temporarily closed most gay bars in the city.

1974: The Golden Gate Business Association (San Francisco): Offshoot of the Tavern Guild.

1975: The Portland Town Council (Portland, OR).

1976: The Greater Gotham Business Council (NYC), Southern California Women for Understanding, Michigan Organization 14 Human Rights.

1977: The Community Business and Professional Guild (Los Angeles): Later became the Business &c Professional :Association of Los Angeles. Orion (Los Angeles): Set up by top young political campaign managers and businessmen.

1979: The Valley Business Alliance (Los Angeles).

1980: The National Association of Business Councils: Headed then by Jean O’Leary and Arthur Lazere, NABC held its first national convention in an Francisco in 1981, with 250 people attending. Representative Pete McClosky addressed them, and Joan Baez performed at the convention. By 1983. NABC included more than 3,00O members in twenty local groups, from Atlanta and Tampa to Milwaukee and Minneapolis-St. Paul.

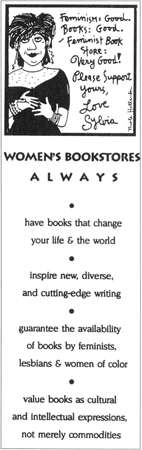

While in Judith’s Room bookstore in New York City recently, I glanced at their newsletter and read an excerpt from the latest newsletter of Old Wives’ Tales bookstore in San Francisco. The gist of the articles was the same. Larger, mainstream bookstores are capitalizing on the trendiness of women’s books and issues, thereby short-circuiting the economies of the feminist bookstores. In addition to the obvious economic repercussions, women’s bookstores are experiencing a collective identity crisis and questioning their viabilty in the women’s communities.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

In 1994, the National Gay Pilots Association (NGPA), headquartered in Washington, D.C., had more than 400 members in forty-five states and five countries. According to the NGPA’s executive director, Ron Swanda, “It is not unusual for us to receive letters from new members exclaiming how, before they learned of the NGPA, they believed they were the only gay or lesbian pilot in the country.”

Once again, feminists and lesbians must reevaluate our politics. Even more effective would be a rehash of Economics 101: Supply and Demand, where the bookstores represent the suppliers and we, the lesbian consumers (attention: all femme shoppers!) represent the demand. Otherwise, our precious bookstores, which are more to us than mere places to make book purchases, will be forced to concede to the Barnes & Nobles of the world. Lest we forget our feminist heritage, women’s bookstores were often our first experience with free space. An excerpt from the essay “Free Space” by Pamela Allen, 1970, recalls this development:

The group experience has helped me to synthesize and deepen my emotional and intellectual understanding of the predicaments of females in this society and of the concerns with which we must deal in building a women’s movement. We have defined our group as a place in which to think: to think about our lives, our society; and our potential for being creative individuals.… We call this Free Space. We have had successes and failures in utilizing this space. Usually our problems stem from our failure to be completely honest with ourselves and each other.… Thus individual integrity—intellectual and emotional honesty…is our goal. It has been a difficult challenge.

If only that challenge had been resolved! The reality is that we face it today. Our commitment is to feminism, to lesbianism, to womanist beliefs with women’s dollars. There is no other solution for the safeguarding and institutionalization of our women’s culture. We must put our money where our mouths are (well, not literally, but it is a woman-to-woman thang!).

Honesty is always the best policy in the case of economic survival; we must honestly evaluate our level of commitment not only to the bookstore owners and operators but also to the many lesbian, feminist, and womanist authors, poets, storytellers, playwrights, humorists, and theoreticians who rely upon us to buy and read their work.

We may feel that because there are a few houses where women’s culture is being cultivated, that the women’s movement is built. While our foundation has been laid, it will take more time before the edifice is secure. That security must be financed by us, its participants. Buy Lesbian, Feminist, Womanist or be prepared to say Good-Bye to our Culture and our Heritage!

—KAREN WILLIAMS

Bookstores have played an important role in the lives of gay men and lesbians for many years. Ever since the late sixties and early seventies, gay/lesbian and women’s community-based bookstores have been in operation. During that time, in every state, many such businesses have opened their doors. Some, like the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookstore and Amazon Bookstore, have managed to survive and thrive for decades. Others have closed due to lack of funds only to be replaced by another store nearby. In 1995, there are nearly 200 gay/lesbian and women’s bookstores in the United States.

The success of many gay and women’s bookstores often has more to do with serving community needs than it does with making a profit. With all gay and lesbian bookstores, but especially with the women’s bookstores, the physical space of the store has been a place to gather for companionship, cultural enrichment, and political organizing. For nearly three decades. gay/lesbian and women’s bookstores have been some of the most visible and enduring entrepreneurial efforts of the gay and lesbian community.

“One day two women came Into Lammas [the feminist bookstore in Washington, D.C.]. They’d been travelling around In this van

and looked a little forlorn. Of course, we were all hospitable then, and so when they asked if they could go upstairs for

a little while, I figured they needed to take a whiz, and so I said, ’Sure.’ One of them went out and got a blanket and a

pillow and they went upstairs. I was running the store by myself and an hour went by, then two hours, and I thought, ’Well,

hmmm.’ So I went up, and the door at the top of the stairs was closed. I looked through the keyhole-and they were having sex!

I thought, ’Well, okay, fine’ and went back downstairs. When they were done, they said, ’Thank you,’ and left. I said they

were welcome. And, I don’t know, I suppose that happened to other women’s bookstores.…”

“One day two women came Into Lammas [the feminist bookstore in Washington, D.C.]. They’d been travelling around In this van

and looked a little forlorn. Of course, we were all hospitable then, and so when they asked if they could go upstairs for

a little while, I figured they needed to take a whiz, and so I said, ’Sure.’ One of them went out and got a blanket and a

pillow and they went upstairs. I was running the store by myself and an hour went by, then two hours, and I thought, ’Well,

hmmm.’ So I went up, and the door at the top of the stairs was closed. I looked through the keyhole-and they were having sex!

I thought, ’Well, okay, fine’ and went back downstairs. When they were done, they said, ’Thank you,’ and left. I said they

were welcome. And, I don’t know, I suppose that happened to other women’s bookstores.…”

MARY FARMER

(Courtesy of Charis Books)

In 1971, as the second wave of feminism was getting under was, three women opened ICI, A Woman’s Place bookstore, in Oakland, California. This was the first women’s bookstore in the country, stocking all kinds of books by, for, and about women. (The “ICI” stood for “Information Center Incorporate.”) From the beginning, A Woman’s Place functioned more as an information and referral center than as a for-profit bookstore. It also shared space with the Women’s Press Collective, one of the first women’s print presses.

At about the same time, a few women started selling feminist and lesbian publications from their front porch in Minneapolis—a project which is now the Amazon Bookstore, the oldest existing feminist bookstore in the United States. Over the next several years, lesbians set up shops across the country in major metropolitan areas as well as smaller communities that not only sold books, but also women’s music records, buttons, bumperstickers, T-shirts, and other women-made craft items. When A Woman’s Place opened, there were barely enough lesbian books to fill one shelf; today, there are so many books available that the women’s stores are sometimes hard pressed to stock them all.

Many of the early feminist stores were collectively run and staffed by volunteers, or owned by women who had other full-time jobs. But regardless of who legally owned the bookstores, everyone in the community often felt she had some ownership in the store. Indeed, in the early seventies and eighties, there was little separation between the lesbian community and the local feminist bookstore. The stores functioned both as cultural centers and as a place gathering places. Charis Books in Atlanta, for example, has sponsored well-attended programs ranging from author signings to poetry readings to political discussions even Thursday night since they opened.

For many women, entering a women’s bookstore was the first act of coming out. Women exploring their sexual identity could find both fiction and non-fiction books, as well as dozens of feminist periodicals and magazines. They also found themselves in safe place to hang out and be around other women in a friendly environment. All of this is just as true today. For worsen who are traveling, the first stop in a new city is often the women’s bookstore. The bookstore staff often spends as much time answering non-book related questions (Where is the women’s bar? How can I find a lesbian doctor? Do you know of any places to rent?) as they do helping customers find the right book (I need to send my parents a book about coming out—what do you recommend? I just met this woman who is a minister—what should I read?)

Over the years, as the feminist and lesbian movements have changed, the women’s bookstores, too, have evolved. Today, lesbian (and gay) culture is more available through mainstream sources, as well as in the gay/lesbian bookstores. Twenty years ago. a reader could not find one book with the word “lesbian” in its title at a mainstream bookstore; today, these stores compete with both the women’s and gay stores for lesbian author readings and events. If access to women’s titles were the only reason for their existence, women’s bookstores would not be needed in the 1990s. But the mainstream stores will never be able to recreate the sense of community and belonging that the women’s stores continue to provide to a significant portion of the women’s community.

—LYNN WITT AND MEV MILLER

In 1988, three other lesbians and I opened Grand Books, a general bookstore in Jackson, Wyoming (population 4,000, tourist population 3 million a year). We needed to employ one and a half of the four of us and decided that opening a bookstore would be a cause worthy of us—and something we would enjoy doing. Thus we began the process of starting a small business.

We didn’t have enough cash of our own and so we needed a loan. We consulted with a woman who was a manager of the local savings and loan. She couldn’t provide a loan, but she did spend a lot of time helping us create a business plan, mentoring us, explaining the ins and outs of banking and financing. She revealed to us how extremely difficult it is to he a woman in banking in Wyoming. At one point, she was having lunch with other women bankers from across the state, commiserating about the sexism in their industry. If they just had the right “equipment,” the men would treat them equally. At the next luncheon, one of the bankers presented each of her fellow women bankers with a necklace charm—a tiny penis and balls carefully sculpted in silver! Now the women would forever know they had the right equipment.

With help from this financial adviser and many others, we formulated a dynamite business plan and went loan shopping. At the first bank, the loan officer said, “It’s too had you don’t have husbands who can sign for you. We have plenty of money to loan.” The second banker sat carefully behind his huge wooden desk and said, “I don’t have anything against you … uh … ladies, per se …” as he rejected our application. By then we were disgusted. For the third and final bank, we dyked ourselves out, carrying briefcases and backpacks. We called ourselves the Lesbian Mafia. We strode into the bank as if we owned it. We got the loan!

But before we could receive the money, the loan had to be approved by the Small Business Administration. The SBA has a rule that no business borrowing money from it can support a particular ideal or philosophy. When it learned that our list of bookstore sections included Women’s Studies and that half of the books in our store would be by women, it decided we were a specialty store and therefore not eligible for a loan. This ruling has been used time and time again to prevent feminists and lesbians from borrowing money. We organized a successful letter campaign (from our lawyer and our book distributors) saying that it would be dumb to open a “specialty” store in such a small town, and we were, after all, smarter than that. We finally got, and repaid, the loan.

We ordered bookstore fixtures that were to be trucked from “back east” and had a crowd of lesbians lined up to help unload the moving van over the Fourth of July weekend. When the Mayflower truck pulled up, we discovered that the two drivers were women and definitely “family.” Their previous delivers had been to a Christian bookstore in Ohio and they were mighty pleased to be delivering to dykes.

In spite of our promises to the SBA, we did carry a wide selection of lesbian and gay books. However, we didn’t want the fact that we carried “those“ books to affect our sales of everything else. For this reason and our own homophobia, we decided to put the lesbian and gay section in the small back room we were using as an office and call it “The Closet.” We put a sign on the door saying “The Closet.” and, in our ads to the lesbian and gay community, we stated that “the books are in the closet.” This made a safe place for local women to peruse the books and gave us a great conversation item with lesbians passing through. Realizing that some dykes would not be brave enough to ask us where the books were. we trained ourselves and our employees to spot and approach lesbians with questions such as “How did you find us?” and “Is there anything else we can help you find?” Our straight employee. Colleen, was sometimes better at spotting and interacting with lesbians and gays than we were.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Today there are more than ninety women’s/feminist bookstores operating, from Alaska to Alabama. While dozens of such stores have come and gone over the years, the stores below are significant because they have been around for at least twenty years:

Amazon Bookstore Minneapolis, MN

Charis Books & More Atlanta, GA

Lammas Women’s Books & More Washington, DC

Mother Kali’s Books Eugene. OR

New Words Bookstore Cambridge, MA

Old Wives’ Tales San Francisco, CA

Sisterhood BookstoreLos Angeles, CA

After hiding the books in the closet for a couple of years, Colleen decided we needed a coming-out party for the books. She brought the books out of the closet and formed a great lesbian, gay, and women’s studies section. Much to our surprise, sales increased and we never did receive a negative comment.

The bookstore was an oasis for locals as well as for travelers visiting conservative Wyoming and nearby states, where openly gay and lesbian organizations are few and far between, and where the spirit of appreciation for sexual diversity is not encouraged. Women coming through would stop to get a “hit” of lesbian culture/energy. This constant parade of lesbians through our doors made us feel wonderful, less isolated, more connected. Even with only a few hours’ notice, we could round up audiences for lesbian happenings.

At the beginning of our second year of business, the bank changed its mind about giving us a $10,000 line of credit. As it stood, we had based our financial plan around that infusion of capital. Friends offered to loan us money to keep the store open, but after four years of Reagan and Bush we were exhausted. In February 1992, we closed Grand Books.

The most fulfilling part of owning a feminist bookstore was also the most demanding. We got to meet and interact with many wonderful people, and we were also expected to be the social service center for the lesbian and gay community. We maintain contact with lots of the great people we met through Grand Books, but it was definitely time to do something else that wasn’t so emotionally taxing.

—DOROTHY HOLLAND

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Under One Roof, a retailing establishment on Market Street in San Francisco’s Castro District, was created to assist AIDS organizations in the city to jointly market their products. Staffed and supported by volunteers, it is the nation’s only gift shop for AIDS relief organizations. All of the money from sales goes to the designated organization supplying the product.

In 1967, two years before the Stonewall Rebellion, a revolution of a different sort was under way. In a tiny retail storefront on New York’s Mercer Street, gay activist Craig Rodwell opened the world’s first gay bookstore, Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop.

Rodwell and his mother, Marian, stayed up all night before the grand opening, “finishing the dozen bookshelves (with about twenty-five titles total),” notes Martin Duberman in Stonewall. “In those years, a ‘gay’ bookstore had meant only one thing; pornography. But Craig had a straitlaced, proper side, and he had decided early on that the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop would carry only ‘the better titles’ and no pornography of any kind.… He was determined to have a bookstore where gay people did not feel manipulated or used. There was no ADULT READING sign in the window, and no peep show in the back room. And the ad Craig later took out in the Village Voice was headlined ‘GAY IS GOOD.’”

In addition to books, the shop carried gay buttons and cards, and it had a community bulletin hoard. The store also acted as a clearinghouse for information, and as a community center for several gay organizations. One of the store’s earliest customers—and one of Rodwell’s lovers—was Harvey Milk.

The success of Oscar Wilde inspired others to enter the risky business of selling gay and lesbian books. By the 1970s, there were gay and lesbian bookstores springing up in other major cities: Glad Day in Toronto (1970). Giovanni’s Room in Philadelphia (1973), Lambda Rising in Washington, D.C. (1974), and A Different Light in Los Angeles (1979). By 1995, there were more than ninety gay and lesbian bookstores in the U.S., with combined sales of more than $30 million a year. Gay bookstores can be found even in many smaller communities today: OutRight Books in Virginia Beach, Virginia, White Rabbit Bookshop in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Phoenix Rising in Roanoke, Virginia.

Meanwhile, the growth of lesbian and gay literature did not go unnoticed by publishing houses. When Lambda Rising opened its doors in 1971, there were only about 300 titles on the shelves—all that were in print at the time. By 1994, there were nearly 15,000 gay and lesbian titles in print, with more than 300 new titles hitting the bookstore shelves in the spring 1994 season alone.

In the 1960s and earlier, it was almost impossible to find gay and lesbian literature in any bookstore. Today, even mainstream chain bookstores frequently offer a gay and lesbian section, and those living in rural or more conservative areas without nearby access to a gay and lesbian bookstore have mail order options for almost any title. The Quality Paperback Book Club made headlines in 1993 by introducing a full line of gay and lesbian titles, and many gay and lesbian bookstores now ship books anywhere in the world for customers ordering by phone, mail, fax, or even e-mail.

Gay and lesbian bookstores give authors and publishers an outlet, but, more important, they provide a valuable service for the lesbian and gay community, making the best literature, information, and resources available to all. Most such stores also serve as de facto community centers, with bulletin boards, handy guide maps, and copies of the local gay and lesbian newspapers. The bookstore staff is usually ready to answer questions about coming out, finding an attorney, or volunteering at a local health clinic, and most gay and lesbian bookstores place as much emphasis on serving the community as they do on selling a book.

—DEACON MACCUBBIN

“The real economic difference between gay and straight Americans is the daily struggle of lesbians and gay men against the

psychological and economic effects of discrimination.”

“The real economic difference between gay and straight Americans is the daily struggle of lesbians and gay men against the

psychological and economic effects of discrimination.”

UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND AT COLLEGE PARK SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS PROFESSOR LEE BADGETT

Although it is a myth that all gay people are wealthy, it would be just as untrue to imply that all gay people are poor. Just as we cross all race and ethnic boundaries, lesbians and gay men also cross all class and economic lines. And while there are some prominent gay philanthropists, whether or not we have a lot of money individually, collectively we definitely have economic clout. The vast majority of our gay and lesbian organizations depend on that support for their economic survival, since there is not much government support, verbally or cash-wise, for queer causes. Even in the private (nongay) sector, those who would lend support to organizations such as the NAACP or the National Asian American Journalists Association, do not necessarily support similar institutions in the gay community.

Statistics show that people in the United States with the least amount of income actually give away proportionately more than the wealthier citizens. As a group, gay people are not at the top of the income pyramid. Nonetheless, most lesbians and gay men can and do donate in varying amounts to everything from the local public radio stations and environmental groups, to AIDS services organizations and national lobbying groups like the Human Rights Campaign Fund. We have learned that we must support our movement our-selves; no one is going to do that for us.

Informally, we have been supporting our community for years, from fund-raising against antigay initiatives to fund-raising in support of gay prisoners’ rights projects. We have started our own foundations and gay-owned businesses, our own PACs and voter education projects. We have funded hundreds of AIDS organizations around the country. We have done all of this and more ourselves, by taking lessons from other communities, by asking each other for money, by teaching each other, and by helping each other to understand that, together, we can make a difference.

This is a story about gay wealth, or at least the unscrutinized perception of gay wealth. This is a story about the much harped-upon $3.5 million that lesbian and gay donors gave candidate Bill Clinton. And about marketing surveys that find gays and lesbians have twice the annual income of straights. Finally, this is a story about how attempts to play up the alleged financial power of the gay and lesbian community inadvertently play right into the hands of the community’s enemies.