Welcome to the 1990s. Amid the chaos of virulently homophobic amendments nationwide, President Clinton’s flip-flop over queers

in the military, and the firebombing of an HIV-positive lesbian activist’s home in Tampa Bay, Florida, a ballsy, out and loud,

four-inch-tall lesbian inside the television yells, “I want my DYKE TV.”

In April 1993, DYKE TV emerged from the ruins of New York City’s AIDS-torn, ozone-challenged, ever-incestuous lesbian community. Now, even. week

gay girls across the country can turn themselves on—and learn a thing or two—in the comfort of their own homes.

It is, however, not the first lesbian cable show. In 1988, Video Salon in New Orleans and Intergalactic Lesbian Video in New Mexico jump-started their Sapphic engines for a short ride and premiered half-hour monthly installments of lesbian

cable programming. And now DYKE TV, the brainchild of executive producers Linda Chapman, Mary Patierno, and Ana Maria Simo, has taken this city’s exceptionally

diverse, political workhorse of a community by storm. The series follows a magazine format, covering both news and cultural

events. In “Lesbian I lealth,” one segment zeroed in on a half-nude dyke with a speculum in her vagina explaining the ins

and outs of cervical self-exam. “The Arts” runs the gamut with film-makers, performers, painters, and dancers. “Sports” has

provided campy and inspiring investigations into local rugby fields, the beloved Brooklyn Women’s Martial Arts, and the truly

sweaty Gay Games IV. There’s at least one in-depth news report at the beginning of each show and a “Calendar” segment at the

tail end. However, the segment to tune in for is called “I Was a Lesbian Child,” complete with old tomboy photos and amusing

reminiscences.

DTV’S historical moment was marked by both the in your-face passion of the Lesbian Avengers, a movement formed to promote our visibility

and survival, and the premiere of Manhattan Neighborhood Network’s two new cable access channels in December 1992. (DYKE TV now airs on one of them.) In turn, the success of DYKE TV marks the birth of other cable shows, like Girl/Girl TV in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Laughing Matters in Cambridge.

Not including the endless in-kind services provided by a veritable legion of volunteers, four segments of DYKE TV cost $3,000 to $4,000 to produce. Seed money was planted by a few small foundations, but otherwise the series relies on homegrown

strategies to raise cash: cock-tail parties and pooled honorariums from university presentations. Furthermore, if you want

to make your own dollars count, and, in Patierno’s words, “to feel a part of it all,” you can become a member with a quarterly

newsletter. Or even better for both you and DTV. become a subscriber and get the quarterly “Best of …” tape mailed to you at home. Needless to say, Chapman verifies that

the show functions on “pretty much of a shoestring.”

Rest assured that media-starved girls-into-girls don’t have to live in New York, Massachusetts, or Berlin (where the collectively

produced Läsbisch TV presents similar fare) to catch dykes on TV. Having beat the bushes for local sponsorships, DTV currently airs on public access channels in seventeen cities from coast to coast. “People like the show and want it on in

their own towns,” says Patierno, so a small business or an individual woman donates $2.500 a year for tape stock, dubbing,

and mailing of the weekly program. As for content, the producers are eager to dig their tripod legs in everyone’s backyard.

Chapman muses, “We definitely want to cover the scene in a bigger way than just Manhattan.” Aiming to present the wider world

of lesbians, they actively solicit volunteer stringers from around the country.

As the “Religious Right” perpetuates intolerance and hatred on their own crystal-clear transponders and satellites, we must

fight for each minute of television airtime. We must learn from them, do as they do, work passionately to take over this nation,

school district by school district, city by city, state by state, and channel by channel. To “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” our

best response is “Make DYKE TV, not war.”

—CATHERINE SAALFIELD

The Barry Z Show (New York, NY)

Be Our Guest (New York, NY)

Being Gay Today (Sacramento, CA)

Electric City (San Francisco, CA)

Gay & Lesbian News (Los Angeles, CA)

Gay Fairfax (VA)

The Gay 90’s (Pittsburgh, PA)

Gay Perspectives (Rockville, MD)

Gay TV (Indianapolis, IN)

Gay USA (New York, NY, and nationally)

Gayblevision (Vancouver, BC)

GAZE-TV (Minneapolis, MN)

Good Morning, Gaymerica! (New York, NY)

Grass Roots (Madison, WI)

In the Dungeon (New York, NY)

In the Trenches (Madison, WI)

Inside/Out (New York, NY)

Inside/Outside the Beltway (Washington, DC)

Between the Lines (Nashville, TN)

The Closet Case Show (New York, NY)

Coming Out! (Winnipeg, MB)

Just for the Record (New Orleans, LA)

The Lambda Report (Denver, CO)

Latinos en Acción (New York, NY)

Lavender Lounge (San Francisco, CA)

LGTV (Lesbian/Gay Television) (Providence, RI)

Lovie TV (New York, NY)

Men for Men (New York, NY)

Network Q (national mail order)

Nothing to Hide (Madison, WI)

One in 10 People (Fairfax, VA)

Out! In the 90’s (New York, NY)

Out on Wednesdays (New York, NY)

Outfront: Gay and Lesbian TV (Cincinnati, OH)

Outlook Video (Mountain View, CA)

Party Talk (New York, NY)

Dish (Los Angeles, CA)

Dishing It Up with T-Gala (Nashville, TN)

DYKE-TV (New York, NY)

Pride Time (Boston, MA)

PRISM (Vancouver, BC)

Slightly Bent News (Portland, OR)

Spectrum News Report (Santa Ana, CA)

Stonewall Place After Dark (New York, NY)

Stonewall Union Lesbian/Gay Pride Report (Columbus, OH)

The 10% Show (Chicago, IL)

The Third Side (Washington, DC)

Thunder Gay Magazine (Thunder Bay, ON)

Tricks (Los Angeles, CA)

Two in Twenty (Because One in Ten Sounds Lonely) (Somerville, MA)

Way Out! (New York, NY)

Yellow on Thursday Milwaukee, WI)

—ANDY HUMM

In the Life is the first regularly broadcast national gay and lesbian series on public television, carried on over sixty stations around

the country. It’s a fun, often lighthearted glimpse of gay and lesbian culture. Started in June 1992, the format of the program

has evolved over time. Earlier shows were like the old Ed Sullivan variety show (hosted by Garrett Glaser or Kate Clinton),

with a panoply of guests ranging from the singing group The Flirtations to actor David Drake, performing a scene from The Night Larry Kramer Kissed Me. Occasionally a show will be theme oriented, like the one that focused on gay and lesbian teens, hosted by comedian Karen

Williams with co-hosts Ron Romanofsky and Paul Phillips of the singing duo Romanofsky and Phillips.

Advertising that it “bridges the gap between the straight and gay communities,” the show has covered such topics as gay country-and-western

life, presented sneak previews of films such as the smash lesbian film Forbidden Love, and provided coverage of both the 1993 March on Washington and the 1994 Stonewall 25 celebration in New York. Other notable

guests over the years have been Lily Tomlin, Bob Hattoy, Tony Kushner, and Melissa Etheridge.

Although the program is sponsored by the Public Broadcasting System (PBS), it receives no funding from PBS or the Corporation

for Public Broadcasting, relying on underwriting and donations from sympathetic foundations and private individuals.

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

In Seattle during the early 1970s, there was a shortlived radio program called “Make No Mistake About It—It’s the Faggot and

the Dyke.” When the “the dyke” repeatedly played the song “Every Woman Can Be a Lesbian” (from the Alix Dobkin album Lavender Jane Loves Women), the FCC attempted to pull the station’s license on the grounds of “obscenity on the air.” Apparently, the L-word airing

more than six times in one hour greatly of fended the FCC. At the hearing, the station retained control of its license, although

“the dyke” was suspended from broadcasting for two years.

Visibility is not only about being seen; it’s also about being heard. Gay men and lesbians have taken to the airwaves around

the country over the past several decades, spreading the words and music of our communities to anyone who could tune in. The

gay radio movement has been moving slowly and steadily for-ward since the 1970s, struggling against high production costs,

strict FCC regulations, and local homophobia.

Today there are radio programs for gay men, shows for lesbians, and co-sexual shows. There are news shows, talk shows, and

women’s music shows. Gay male radio can trace its roots as far back as Allen Ginsberg’s reading of Howl on Berkeley’s public radio station KPFA in the fifties. Growing out of lesbian-feminist separatism in the seventies, lesbian

radio collectives brought out fresh new voices, many of which continue today.

Despite its continuing struggle with financial and censorship issues, gay and lesbian radio is here to stay as one of the

most accessible ways to reach gay and lesbian communities in cities and suburbs around the country.

Memories are foggy and the tapes may no longer exist, but let’s just say the first truly gay radio broadcast occurred whenever

Allen Ginsberg first “Howled” on Pacifica Radio’s KPFA in Berkeley, California, the nation’s first successful noncommercial

station. The language, rhythms, meaning, and in-your face intensity of Ginsberg’s Beat manifesto were quite unlike any message

American radio had ever transmitted.

While Ginsberg’s descent-into-hell imagery would resonate with a later generation of post-Stonewall out of the closet gay

men, most of KPFA’s early programs on same-sex love, such as the 1963 broadcast “Live and Let Live,” stopped considerably

short of proclaiming gayness a normal way of life, let alone echoing Ginsberg’s belief that normality itself might be a form

of madness.

For many years, the only toehold gay people had on the broadcast band was at those stations flying the banner of the Pacifica

foundation. Created in 1946 by pacifist/journalist Lewis Hill to give Americans an alternative source of news and information

from that provided by advertiser-backed corporate radio, Pacifica eventually grew into a looser network of five stations:

KPFA (Berkeley), KPFK (Los Angeles), KPFT (Houston), WBAI (New York City), and WPFW (Washington, D.C.). Fortuitously, the

five Pacifica stations served metropolitan areas with the largest concentrations of gay men and lesbians. Until the 1970s,

virtually all of Pacifica’s programs on gay subjects were under the aegis of the news, public affairs, or drama and literature

department.

Many people are not aware that in 1964, a landmark decision by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) upheld Pacifica’s

contention that the public was well served by gay-themed broadcasts “so long as the program is handled in good taste.” However,

an ominous foreshadowing of just how short the FCC leash on gay programs might turn out to be came in a separate statement

by conservative Commissioner Robert E. Lee to the effect that “a microphone in a bordello, during slack hours, could give

us similar information.”

Beginnings

One of the earliest gay programs acknowledged its connection to Ginsberg by naming itself “Sunshine Gay Dreams” (later shortened

simply to “Gay Dreams”). The program has served Philadelphia continuously since 1972 on WXPN-FM. For the remainder of the

1970s, it seemed that at least one new program sprang up every year: “Fruitpunch” (KPFA, 1973), “IMRU” (KPFK, 1975), “Wilde

’N Stein” (KPFT, 1975), “Just Before Dawn” (KCHU, Dallas, 1975). And in 1976, “The Gay Life” began on San Francisco’s KSAN

(now a country. music station), one of the first gay programs to be regularly scheduled on a commercial station.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

The earliest known broadcast reference to homosexuality was in 1930, when Oregon politician Robert G. Duncan bought two hours

of radio time per day on KYEP radio in Portland to blast the people he blamed for his recent defeat. The Federal Radio Commission

(FRC) later deemed his comments “obscene, indecent, and profane.” In one of the suspect remarks, Duncan accused a local newspaper

of shielding “sodomites.” In 1930, homosexuality was so taboo that one was not supposed to mention it on the air, even to

condemn it.

—STEVEN CAPSUTO

“Fruitpunch” began Monday night, June 4, 1973, under the bland title, “Gay Talk.” Subscribers to the KPFA program guide, The Folio, were promised that “Gay Talk” would inform and educate straight and gay listeners alike, while showing gay men that they

were not alone.

Former Fruitpuncher Philip Maldari recalls that the original collective members were recruited en masse one night at a gay

coffeehouse in downtown Oakland. “Forty men from the East Bay were all asked if they would like to be on the radio,” Maldari

explains. “Everybody wanted to be a media star,” says another ex-collective member, Christopher Lone. “People wanted to read

their own poetry and play their own music, but nobody wanted to edit tape or do the hard-core production work. Some people

dropped out for political reasons. They thought there was very little support from the station—that we were on the air as

a result of tokenism—a way for KPFA to show how liberal it was.” By the end of the first year, that forty had dwindled down

to a handful, which is the size of the collective today.

The Jerker

For roughly the first twenty years, gay radio’s howl was a barely audible whisper across the corridors of white noise emitted

from America’s more than 7,000 broadcast radio stations. On August 31, 1986, one gay broadcast burst through the white noise

and became the focus of an intense debate about what is and is not fit for American ears.

That summer night, the Reverend Larry Poland was listening, he says, quite by accident to the weekly edition of KPFK’s gay/lesbian

program “IMRU (I Am, Are You?).” Reverend Poland, a Los Angeles area Christian fundamentalist minister, says he was deeply

shocked and offended by what he heard. What Rev. Poland and thousands of Los Angeles listeners heard was excerpts from an

AIDS-era safe-sex drama called Jerker. The late Robert Chesley, San Francisco playwright and author of Jerker, called his play “a pornographic elegy with redeeming social value.” Jerker depicts the masturbatory fantasy relationship between two gay men whose sex lives have narrowed down, because of AIDS, to

what can be described over the phone. Eventually one of the buddies reaches a disconnected phone—his discovery that his unseen

friend has succumbed to the disease.

Reverend Poland complained the next day to the FCC that KPFK’s broadcast of Jerker “did violence to me and my family. They potentially took away my control of being able to protect my children from learning

about certain sexual practices at certain times in their lives.” Playwright Chesley argued back that Poland and other would-be

censors were asking the government to commit a far worse act of violence against the sexually informed members of the radio

audience. “Prudery kills, on the radio or anywhere else. From the teenage girl who gets pregnant and takes her own life, to

the young gay man who is still in the closet and doesn’t understand the danger of AIDS, prudery kills. Nobody ever died from

being offended by what they hear or see.”

The broadcast of Jerker prompted the FCC to threaten to revoke the license of KPFK, and to set new guidelines considerably restricting the discussion

of sexually sensitive issues by gay and lesbian broadcasters. Some observers noted a double standard invoked by the FCC, holding

gay broadcasters to a more stringent set of language rules than those imposed on the commercial “shock jock” Howard Stern,

for example.

Moving Ahead

As elsewhere in the competitive media world, gay radio has had its share of winners and losers. In Dallas, the program “Just

Before Dawn,” one of a handful of cosexually run shows, did not outlast the demise of its originating station, KCHU, and it

was seven years before another gay and lesbian program had airtime in that city. The first attempt at a national gay radio

network was in 1983 in San Francisco, and was called, appropriately, the National Gay Network. With the motto “National Gay

Network: They Broke the Silence,” NGN broadcast three times a week and was a source for both news and features to lesbians

and gay men on several continents. Unfortunately, the two men who produced NGN, Tim O’Malley and Steve Lawson, found the financial

and personal stress to be too great, and abandoned both their relationship and the show in late 1985.

Success

One major success story of the 1980s that has continued into the nasty 1990s is the Los Angeles-based nationally syndicated

program “This Way Out.” Greg Gordon and Lucia Chappelle are cohosts/producers of the satellite-distributed half-hour show.

Gordon, who admits he was burned out and bored after ten years of volunteering for “IMRU,” says that “This Way Out” is not

aimed merely at the consumers of existing local gay programs around the country. “I want a program that is as entertaining

and informative as possible, a program that will appeal to the scores of potential listeners who won’t listen to public radio

because of its pacing and content.”

The heart of “This Way Out” consists of short reports from all over the world: the sounds of demonstrators in London protesting

the antigay Clause 28, the story of a gay man protesting the ban on same-sex slow dancing at Disneyland, the latest on antigay

organizing in Idaho. Both producers see their program as supplementing the already established gay programs, and hope to expand

“This Way Out” is coverage of international stories and people of color in the United States.

Growing Toward the Future

Gay radio never seems to stay put. Shows change program times, come in and out of existence, and change staff with a good

deal of frequency. Still, many of the people who have been involved throughout the years remain involved today. As the gay

men and lesbians who develop gay radio continue to learn from the successes and failures of themselves and others around the

country, grass-roots foundations have been laid for the future. Gay radio may always be changing, but it is here to stay.

— DAVID LAMBLE

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

In 1975, Frieda Werden, who later co-founded Women’s International News Gathering Service with reporter and producer Katherine

Davenport in Austin, Texas, produced what she believes was the first nationally syndicated multipart series on homosexuality.

“What’s Normal?” was broadcast in 1975 in thirteen half-hour segments on the Longhorn Radio Network, based in Texas. Although

only thirteen of Longhorn’s nearly 600 commercial and non-profit affiliates aired “What’s Normal?”, Werden says it received

more mail than any previous Longhorn series. To encourage letters, Werden offered a bibliography to every listener who wrote.

Most radio programming produced for, about, and by lesbians grew out of the feminist movement of the 1970s. In those heady

days of the women’s liberation movement, women’s radio collectives sprang up at community radio stations around the country.

Among the earliest was Sophie’s Parlor Media Collective, which actually began as Radio Free Women at Georgetown University’s

radio station in Washington, D.C., in 1972. At that time, according to Moira Rankin in a 1992 interview with D.C.’s Woman’s

Monthly, “with all of the misogyny and homophobia, it was pretty courageous and audacious to go on the air with an all-woman

production featuring women’s music and women’s issues with no men.”

Rankin, a collective member from 1974 to 1985, went on to a successful career in public radio. In 1977, Sophie’s Parlor moved to Pacifica network’s WPFW, where it is still broadcast.

As on many feminist radio programs, lesbians and lesbianism were often included in both the music and public affairs segments.

On one early Sophie’s Parlor program, Ginny Berson and Meg Christian interviewed singer Cris Williamson. According to Berson,

Cris was joking around and said something like, “I know—why don’t you start a women’s recording company?” “A light-bulb went

off over my head,” Berson said, and Olivia Records (and an entire movement) was conceived. The women of Sophie’s Parlor also

created a notorious public affairs special about Lesbian nuns.

Frieda Werden, producer and co-founder of Women’s International News Gathering Service (WINGS), says the mid-1970s saw “a

wave of women’s radio collectives. Some were mainly lesbian, some were not.”

In 1976, the Feminist Radio Network formed in Washington, producing and distributing tapes nationally on women’s issues. In

1979, FRN issued a catalog listing forty-nine women’s programs throughout the U.S.; by 1985 the number had grown to eighty

women’s programs on forty-three stations.

While some stations aired women’s news and information programs, “wimmin’s music,” says Werden, was especially important at

the many stations that didn’t allow any spoken-word feminist or lesbian programming. Women’s music, although often very political,

was not seen as threatening and more easily lit into many stations’ formats.

In places where gay programs already existed, lesbians sometimes split from co-gender shows. Werden says that for men, radio

was too often an ego thing. “Very rarely would you see men, even gay men, working in collectives,” says Werden. Such a split

occurred al WXPN in Philadelphia, where, according lo “Gaydreams” producer Bert Wylen, “lesbian separatists invaded” and formed

“Amazon Country.” which “didn’t; want any male voices.”

Helene Rosenbluth, producer of “Lesbian Sisters” at Pacifica’s Los Angeles station, KPFK, from 1976 to 1986, said the rise

of the women’s movement “made it more difficult to work with gay men who were not working on sexist issues. Just because we

were all gay, didn’t mean we could ail sit at the same table.”

About producing “Lesbian Sisters,” Rosenbluth says it was “incredible” to hear stories from listeners who said the program

helped them come out. “They didn’t feel crazy anymore, like they were the only ones. The power of radio is amazing.”

Although most feminist programs started at noncommercial stations, the story’s a little different in Boston. There, the firing

of a female DJ at progressive commercial rock music station WBCM started a chain of events that Melanie Berzon says led to

women’s shows in the area.

Berzon, who now makes her living in public radio, says the DJ, Dinah Vapron “got politicized and feminized” through the Boston

women’s movement. She started saying things and playing music management didn’t like. The women’s community mobilized around

her firing in 1973, and demanded WBCM rehire Vapron and devote time to a women-run show. WBCM didn’t rehire Vapron, but they

conceded to the women’s show, and the Red Tape Collective, made up of lesbians and straight women, was given an hour a week.

Today, both women’s programs and specifically lesbian programs air locally and regionally at many stations, and WINGS continues

to cover lesbian issues along with other women’s issues in its internationally distributed programs. But WINGS producer Frieda

Werden says women’s airtime is diminishing overall at most stations, both commercial and noncommercial.

Helene Rosenbluth, former “Lesbian Sisters” producer, who continues to work in women’s radio at KPFA in Berkeley, says it

may be time to think of other, creative ways to work women’s and lesbian and gay issues into existing mainstream programs.

“It’s not the seventies anymore,” says Rosenbluth. “The kinds of formats we loved to do back then aren’t working anymore.”

At a National Lesbian and Gay Journalists conference in 1994, she suggested a need to “re-instill ourselves so that we’re

not just lesbian or gay broadcasters.

“You have to find out what they will air, not just what you like to do. If no one hears it, what good is it?”

—ERIC JANSEN

“This Way Out,” the Los Angeles-based gay and lesbian radio news and features program, broadcasts on more than forty stations

across the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia. Here is a list of some of the other major programs from around the

country:

“Arts Magazine”

Mondays at 3 p.m.

WBAI 99.5 FM New York City

“Fresh Air/Fresh Fruit

Thursdays at 7 p.m.

KFAI 90.3 FM Minneapolis/St. Paul

“Fruitpunch”

Wednesdays at 7 p.m.

KPFA 94.1 FM Berkeley, California

KFCF 88.1 FM Fresno, California

“Gay Dreams”

Sundays at 9 p.m.

WXPN 88.5 FM Philadelphia

“Gay Graffiti”

Thursdays at 7 p.m.

WRFG 89.3 FM Atlanta

“The Gay Show/Outlooks”

alternate Sundays at 7 p.m.

WBAI 99.5 FM New York City

“Ghosts in the Machine”

Wednesdays at 9:30 p.m.

WBAI 99.5 FM New York City

“Hibernia Beach”

Sundays at 7 a.m.

KITS 105.3 FM San Francisco

“House Fairy”

(call station for times)

WRAS 88.5 FM Atlanta

“IMRU”

(call station for times)

KPFK 90.7 FM Los Angeles

“Lavender Wimmin”

Thursdays at 6 p.m.

WUSH 90.1 FM Stony Brook. New York

“Radical Talk Show”

Saturdays at 5 p.m.

WIGO 1340 AM Atlanta

“Straight Jacket”

Mondays at 12 p.m.

KALX 90.7 FM Berkeley, California

“Wilde ’N Stein”

(call station for times)

KPFT 90.1 FM Houston

“Women’s Forum”

(call station for times)

WRFG 89.3 FM Atlanta

— DAVID LAMBLE

Probably more than any other minority group, gay men and lesbians have looked to the written word for evidence of our existence.

Lesbian and gay readers and scholars have spent untold efforts to discover if a particular favorite writer was homosexual,

or to see if perhaps homosexuality has been “coded” into a story. Because lesbian and gay readers want and need to have our

experiences and lives validated in the stories we read, we persist in trying to uncover the truth about authors whose sexualities

have been “straightened up” by biographers and historians, as well as correct the distortions in the ways many stories about

love and sex (among other things) have been interpreted by nongay critics and readers.

Of course, many difficult questions arise when we begin to investigate what writers who have lived in different historical

and cultural contexts meant when they described love between men or love between women. Writers whose sexual orientation today

we would describe as gay, lesbian, or bisexual have been a part of every literary form throughout history. From Albee, Alther,

and Arenas, to Barnes, Baldwin, and Aphra Behn, from Sappho, Shakespeare, and Gertrude Stein, to Whitman, Wittig, and Woolf,

the list goes across history, languages, nationalities, and colors, and includes poets, playwrights, and novelists. Just as

gay authors have always existed, so too have gay characters and themes been present throughout literature, regardless of the

sexual orientation of the writer. Carmilla, vampire and predecessor to Count Dracula, was a lesbian. Stephen Gordon became

the most embattled butch in the English-speaking world in 1928 when The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall was banned in England (where it remained banned for thirty years). James Baldwin wrote some of the most

powerful and enduring depictions of love between men. Virginia Woolf wrote Orlando (1928) for her beloved Vita Sackville West. And the novels of E. M. Forster and Edmund White have been regarded as homoerotic

in tone and imagery.

Contemporary gay readers cannot only find images of ourselves in traditional literature, but we also live at a time when there

has been an emergence of explicitly gay writing by and for gay and lesbian readers. We can move beyond proving that we exist

to raise other questions about how we live and what shapes our experience.

Mainstream publishing houses now produce some gay and lesbian writing. For gay men, the struggle to be published in large

houses is still difficult, but for lesbians it still is often impossible. Thanks to lesbian and gay presses, openly lesbian

and gay male writers are published in larger numbers than ever before. Especially for lesbians, publishing from within the

community provides access to audiences that may not otherwise be available. Never again will lesbian and gay readers be dependent

on heterosexual writers for descriptions of our triumphs, pains, and joys.

Lesbians and gay men have been the subjects of fiction in all literary genres. In 1799, Charles Brockden Brown’s novel Ormond was published, which contained the first knower favorable description of lesbianism in American fiction. Other mid-17th century

writers nibbled around the edges of homosexuality in their novels as well, and many of the poor-but-virtuousboy-makes-good

novels of Horatio Alger, Jr., have homocentric elements. In the 19th century, the poet Walt Whitman hints at homosexuality

in his obscure temperance novel Franklin Evans.

The following list documents some of the earliest gay-themed novels, with an emphasis on books with positive lesbian and gay

characters.

| 1800s |

| 1870 |

Joseph and His Friend by Bayard Taylor

|

| 1887 |

White Cockades by E. I. Prime-Stevenson

|

| 1891 |

Left to Themselves by E. I. Prime-Stevenson

|

| 1894 |

Marriage Below Zero by Alfred J. Cohen

|

| 1900s |

| 1908 |

Imre by Xavier Mayne (pen name of E. I. Prime-Stevenson)

|

| 1908 |

The Intersexes by E. I. Prime-Stevenson (nonfiction)

|

| 1920s |

| 1928 |

The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall

|

| 1928 |

Remembrance of Things Past by Proust

|

| 1930s |

| 1931 |

The Loveliest of Friends by Sheila G. Donisthorpe

|

| 1931 |

Strange Brother by Blair Niles

|

| 1931 |

Twilight Men by Andre Tellier

|

| 1933 |

The Better Angel by Forman Brown (pen name of Ralph Meeker)

|

| 1933 |

Scarlet Pansy by Lou Rand Hogan (pen name of Robert Sculley)

|

| 1933 |

The Young and Evil by Parker Tyler and Charles Henri Ford

|

| 1935 |

We Too Are Drifting by Gale Whilhelm

|

| 1937 |

Either Is Love by Elisabeth Craigin

|

| 1938 |

Torchlight to Valhalla by Gale Whilhelm

|

| 1939 |

Diana by Diana Fredericks

|

| 1940s |

| 1941 |

The Little Less by Angela DuMaurier

|

| 1943 |

Winter Solstice by Elisabeth Craigin

|

| 1948 |

The City and the Pillar by Gore Vidal

|

| 1949 |

Olivia by Olivia (pen name of Dorothy Bussy)

|

| 1949 |

Stranger in the Land by Ward Thomas

|

| 1950s |

| 1950 |

Quatrefoil by James Barr

|

| 1950 |

Things as They Are by Gertrude Stein

|

| 1951 |

Divided Path by Nial Kent (pen name of William Leroy Thomas)

|

| 1951 |

Finistère by Fritz Peters (pen name of Arthur Anderson Peters)

|

| 1952 |

The Price of Salt by Claire Morgan (pen name of Patricia Highsmith)

|

| 1955 |

The Last Innocence by Celia Bertin

|

| 1955 |

Remembrance Way by Jessie Rehder

|

| 1956 |

The Hearth and the Strangeness by N. Martin Kramer (pen name of Beatrice Ann Wright)

|

| 1958 |

Rings of Glass by Luise Rinser

|

| 1958 |

The Wheel of Earth by Helga Sandburg

|

| 1959 |

Heroes and Orators by Robert Phelps

|

—JIM KEPNER AND BARBARA GRIER

“Sophisticated, witty, attractive Val MacGregor was one of Inter-American’s most popular stewardesses.… Then one day lovely,

dark-haired Toni was assigned to be her co-stewardess. From their first moment of meeting Val sensed something oddly disturbing

about the girl. Not until later did she realize what she was — and then it was much too late!”

“Sophisticated, witty, attractive Val MacGregor was one of Inter-American’s most popular stewardesses.… Then one day lovely,

dark-haired Toni was assigned to be her co-stewardess. From their first moment of meeting Val sensed something oddly disturbing

about the girl. Not until later did she realize what she was — and then it was much too late!”

FROM THE BACK COVER OF EDGE OF TWILIGHT

Welcome to the post-Well of Loneliness, pre-Rubyfruit Jungle world of lesbian pulp fiction. For lesbians who came out during the fifties and early sixties, their first ties to the lesbian

world were often the “Twilight Women” of these novels. This may also be true for women who came out much later. In December

of 1986 as a student at the University of Michigan, I responded to my first notions of being a lesbian by going to the Undergraduate

Library. There I stumbled upon a three-book series by Ann Bannon (of which Women in the Shadows is the middle). It was finals time and I spent a lot of hours in the library—but not studying. I never did check any of those

books out, but I read them all. Here’s a look at it few.

The Covers

One cannot help but wonder at the extravagantly melodramatic cover art and text which often has so little to do with the actual

book that it could be readily exchanged from one book to another and he no less appropriate. The covers are almost universally

sensationalized and some are downright homophobic—even if the book is not (like Twilight Girl). The lesbian world, according to these covers, is a twisted, twilight one, full of angst-ridden women who are trapped by

the irresistible enticements of another woman. The covers reflect the perceptions of an intolerant society toward lesbianism—that

is, that lesbians are sick people living in a dim, unhappy world who lure young innocents to join them in their pell-mell

debauchery.

From a contemporary perspective, it seems the books were marketed this way for several potentially overlapping reasons. In

order to avoid the wrath that might befall the publishers if they were perceived by the public to be printing novels sympathetic

to lesbians, the covers made it appear that they were not. In addition, the buxom femmes obviously broadened the appeal of

the books, making them marketable to straight men as well. Finally, the dissonance between covers and content illustrated

the struggle for lesbians at the time. In some ways, the moralist covers took the guilt out of a “guilty pleasure” by simultaneously

indulging in and disclaiming it.

But lesbians who picked their way through the verbal minefield of the covers often discovered stories that resonated with

their own experience, perhaps for the first time in their lives.

The Books

The books themselves can be broken down into several broad categories:

• Stories where the woman accepts her lesbianism and at the end has hope of happiness. Examples include The Twisted Year and Edge of Twilight—that’s right, popular stewardess Val MacGregor is a lesbian who is going to live happily ever after, finally.

• Stories where the woman accepts her lesbianism but faces a life brimming with tragedy, like Twilight Girl.

• Stories where the woman winds up with a man at the end (which some people might consider tragedy). But often these novels,

like Women in the Shadows, have secondary characters who are lesbians and who are happy and who are not going to wind up with men.

• Stories written by men. While the covers may look sort of similar (though perhaps more sensationalized), the books themselves

are quite different. First, male characters typically play a more significant role in the books written by men. Lesbians are

almost uniformly nymphomaniacs and many are not particular at all whom they sleep with. There is also a peculiar male fear/fantasy

dynamic. In the male-written books it is accepted as something of a truism that once a woman has had sex with another woman

she will never go back to men. The men seem afraid that lesbians have some mysterious sexual tricks men cannot fathom, but

this also makes these women the ultimate conquest, the ultimate test of virile manhood.

The Character

Most of the characters, and certainly the main characters. are not what was/is considered stereotypical. They are almost all

“lovely” and “feminine.” and so apparently “normal.”

Twilight Girl does establish the butch/femme dynamic that was so much a part of the lesbian bar scene in the fifties and early sixties,

though interestingly the very definitely butch main character is described on the cover as “a pretty teenager enticed into

forbidden practices by older girls” and the girl pictured on the cover oozes femme.

Some of what is in these books may make us cringe—or chuckle—today, but for the fifties and sixties the books were daring.

And they were a lifeline for lesbians struggling for some sort of definition of themselves.

They have earned their place as a treasured (albeit sometimes goofy) part of herstory, charting lesbians’ burgeoning sense

of identity and of community even in those still highly oppressive times. Someday, they will stand as a permanent record of

what has turned out to be the crest of an enormously volatile time in the lesbian/gay rights struggle. They give a glimpse

of pre-Stonewall life, with the promise of a more tolerant future butting against an intolerant present.

Plus, they’re kind of fun.

—TERRI L. SMITH

Overwhelmingly, the literature and novels available to most of us to read, the lyrics of the songs we listen to, the images

that we see on the screen, large and small, are heterosexual. As a rule, gay and lesbian people are not in the picture. How,

then, do we validate ourselves, create ourselves, learn to love and grow, when we do not see ourselves reflected back to us

from the world at large? Among other strategies, we build communities, we create our own “families,” we create our own images.

We also “read between the lines,” and underneath the text, trying to determine if an author or singer is gay. We look to see

if perhaps there is some hidden theme, some other way to interpret what we see and read that would allow us to identify with

the story being told. We seek out songs that have neutral genders (“we” and “you,” not “he” and “her”). And we write our own

books.

But when those strategies fail, or when we don’t have access to gay and lesbian literature, we find other ways to put ourselves

in the picture. This is easy to do with songs; it’s pretty simple to change the gender in the lyrics, replacing “him” with

“her,” “he” with “she,” even “man” with “woman.” Doing this with literature, often called “guerilla reading,” is a little

more complicated.

Perhaps you are reading a book in which there is a romantic love triangle: two men love the same woman. If you are a gay man

reading this book, you might put yourself in the role of the woman being fought over. You might put yourself in this story

as male; on the other hand, you might choose to see yourself as female. Or you might go another route and look at the action

between the two competitors as a story with its own homoerotic energy.

Or take a standard girl-meets-boy romance story. If you are a lesbian reading this, you might just close the book and decide

to go for a walk instead. Or you might get inspired by the great writing and decide to overlook the fact that the two main

characters are an opposite-sex couple, and imagine them as a same-sex couple instead. Or you might try more actively to put

yourself in the picture by putting yourself in the role of the pursuer (or the pursued), and read all of the action from that

perspective.

Still another approach to this literary dilemma would be to simply appropriate one or more of the characters, and build your

own story. More than guerilla reading, this probably falls into the realm of fantasy. But who among us has not found a character

in a novel whom we think about long after the book is finished, wondering what would have happened to him or her if the author

continued the story? Or, feeling dissatisfied with the way the author has handled the story, how many times have we created

our own homoerotic endings to heterosexual novels?

—LYNN WITT

“I see a lot of books by lesbian publishers coming through the cataloging stream at the Library of Congress, so I was not

surprised to see a book called South-East Fen Dyke Survey on the book truck today. I was curious, however, to find out what sort of group the South-East Fen Dykes were. I supposed

they were perhaps some sort of rural lesbian collective that staked out part of the Everglades as a commune. I was disappointed

to discover that the book was all about drainage projects in rural England, and had nothing to do with lesbians. Too bad.

A perfectly good name going to waste.”

“I see a lot of books by lesbian publishers coming through the cataloging stream at the Library of Congress, so I was not

surprised to see a book called South-East Fen Dyke Survey on the book truck today. I was curious, however, to find out what sort of group the South-East Fen Dykes were. I supposed

they were perhaps some sort of rural lesbian collective that staked out part of the Everglades as a commune. I was disappointed

to discover that the book was all about drainage projects in rural England, and had nothing to do with lesbians. Too bad.

A perfectly good name going to waste.”

FROM AN ANONYMOUS GAY LIBRARIAN

While gay and lesbian characters were once virtually nonexistent or relegated to the roles of murder victims in mainstream

mystery novels, during the last fifteen years they have taken their place as integral figures in the genre—in mainstream books

by well-known authors, as well as overtly gay-themed novels.

The use of gay and lesbian characters in mystery novels can be traced back to the nineteenth century. The earliest lesbian

reference—and a major one at that—is in Honore de Balzac’s La Fille aux Yeux d’Or/The Girl with the Golden Eyes (1834), in which the title character loves both a young man and his half sister. Arguably, Charles Dickens’s last, unfinished

novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), has a central gay character in John Jasper, who has a “womanish” devotion to his nephew, Edwin Drood. Drug use was

often linked to homosexuality in early mystery novels, and here John Jasper is an opium addict. There is a strong possibility

that had Dickens lived to finish out this novel, Jasper might have been shown to have murdered Edwin Drood out of jealousy

over the boy’s fixation with Rosa Bud.

While many consider the mystery novel a twentieth-century innovation, nineteenth-century writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle gave

us two of our first modern gay characters. The creator of Sherlock Holmes (a character whose relationship to Dr. Watson is

open to interpretation) published Round the Fire Stories in 1909. One of the stories, “The Man with the Watches,” concerns a young homosexual American who is led astray by an older

gay man. When the young man is killed as a result of his brother’s actions, the older man says to the sibling, “You loved

your brother, I’ve no doubt; but you didn’t love him a cent more than I loved him, though you’ll say that I took a queer way

to show it.”

In a period when homosexuality could not be named as such, Doyle’s work reflects a remarkable dialogue. It was not until 1930

that another gay character appeared on the scene—in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon. Three of the figures in the novel—Joel Cairo, Casper Gutman, and his gangster sidekick Wilmer—are all presumed homosexual,

but only the last is openly described as such with the use of the slang term “gunsel” (meaning catamite). A year earlier,

British novelist Gladys Mitchell had introduced the first modern lesbian figure in the mystery genre in Speedy Death. The woman in question appears as a man named Everard Mountjoy, who is murdered in his/her bathtub. Mitchell’s heroine, Beatrice

Adela Lestrange Bradley, who appeared in some sixty-five novels, is able to identify “sexual perversion” as the theme behind

the killing. “Not a pleasant subject,” responds the chief constable. to which Mrs. Bradley replies, “I do not propose to discuss

it”—end of topic!

Homosexuals as murder victims became a common theme in the next four or five decades—and if they were not victims, they were

villains. British writer Richard Hull was the first to use a gay character as the narrator of a mystery novel with The Murder of My Aunt (1935), but unfortunately he is a “pansy boy” without a single redeeming quality and eventually, of course, he is killed

off. The acerbic and witty tone of Hull’s novel was recreated in the 1960s by George Baxt with a series of three outrageously

gay mystery novels: A Queer Kind of Death (1960), Swing low, Sweet Harriet (1967), and Topsy & Evil (1968). In A Queer Kind of Death a gay killer gets away with murder after promising to become the lover of the NYPD officer investigating the case.

Michael Nava, aside from being a prolific an award winning mystery-writer, cowrote with Robert Dawidoff Created Equal: Why Gay Rights Matter to America, a nonfiction political work. (Tom Bianchi)

Generally, the classic writers of the genre during this period steadfastly ignored gay and lesbian characters. In Nemesis, the last novel to feature Miss Marple (1971), Agatha Christie does introduce a lesbian murderess—and treats her harshly.

Ngaio Marsh, who was positively homophobic, has gay characters in a number of her mystery novels; they are usually drug addicts

with a fondness for dressing in female attire. Dorothy Sayers also had a number of lesbian minor characters.

By the 1970s, not only had gay characters started to become sympathetic, but also a number of openly gay authors had embraced

the mystery genre. Nathan Aldyne (the pseudonym of Michael McDowell and Dennis Schuetz), Richard Stevenson (the pseudonym

of Richard Lipez), and most important, Michael Nava, began to write novels with gay themes and gay characters that crossed

the dividing line between gay and straight literature. Their heroes were gay but that did not mean that their readership was

necessarily so. At the same time, Sarah Caudwell began a series of novels featuring a female lawyer who is sexually ambivalent.

The new school of British mystery writers, led by P. D. James and Ruth Rendell, routinely introduced gays and lesbians as

secondary, and sympathetic, characters in their novels.

In Reginald Hill’s popular series of 1980s novels, he integrates a gay character in the form of Sergeant Wield, a closeted

homosexual who fits no gay stereotype. Sergeant Wield is ugly, always ready for a fight, and while quiet about his private

life around the police stations is not above admiring a young police cadet’s bare chest in the locker room. The American equivalent

of Wield is LAPD Sergeant Milo Sturgis, who works closely with straight child psychologist Dr. Alex Delaware in the novels

of Jonathan Kellerman. As explained in Kellerman’s first novel, When the Bough Breaks (1985), Sturgis “wasn’t in the closet, neither did he flaunt it.”

The most prominent of the gay private detectives is insurance investigator Dave Brandstetter, introduced by author Joseph

Hansen in the 1970 novel Fadeout. Nine novels later, readers said good-bye to Brandstetter in A Country of Old Men (1991), which ends with his death from a massive heart attack. Yet again, here was no stereotypical gay character. Brandstetter

was, like his creator, forty-seven when he made his first appearance; he has been involved in two long-term relationships

in the course of the novels; he fends off somewhat implausible approaches from much younger men and expresses an active dislike

for effeminate behavior. (This despite his first lover, recently deceased when the series begins, being “nelly,” an interior

decorator “one cut above a hairdresser.”)

After more than a century of mystery writing, not only could gays and lesbians be identified as such, they could be depicted

as no different from any other novel character. As novelist Hill points out, “It seems to me that any novelist whose picture

of life does not contain homosexual characters is like a landscape painter whose trees are always oak or pine. It may be art

but it surely isn’t life!”

—ANTHONY SLIDE

I was hit with the detective fiction bug in the early 1980s, shortly after I moved to San Francisco. Like so many readers,

I first walked those mean streets with Hammett, Chandler, and James M. Cain. In fact, I became obsessed with the Dashiell

Hammett myth—I trekked San Francisco’s fabled hills, haunted downtown neighborhoods, wandered moodily through fog-shrouded

nights. I even went to work for Pinkerton’s, Hammett’s agency, to see what it was like to be a private eye. Finally, after

almost ten years of immersion in the detective milieu, both literary and real, I was able to launch a series with my own fictional

P.I., Nell Fury.

From the start, I knew Fury would be a lesbian. I was a lesbian, out of the closet, and political; I wanted the same for my

protagonist. Not only was it natural to write from my experience, but I wanted to bring lesbian concerns front and center,

and develop a series that would be funny, sexy, and contemporary. Fury is a dyke dick from the hard-boiled school of private

eye novels, and—happily—she now shares the mean streets with a whole slew of feminist colleagues. The tough, autonomous female

detective came of age in the eighties. I was adding my distinctly lesbian voice to a mix that included superstars like Sue

Grafton and Sara Paretsky, as well as newcomers Patricia Cornwall, Barbara Neeley, Karen Kijewski, and many more.

Lesbian and gay detective fiction also made a big leap forward during this era. In the old days, mysteries that did mention

us usually made being gay an indication of a character’s pathology, or a twisted secret revealed in the unraveling of a perverse

plot complication. Then came the groundbreaking efforts of authors such as Barbara Wilson, Joseph Hansen, and M. F. Beal.

Suddenly, a spectrum of lesbian and gay characters—heroes and otherwise—began emerging. With Nell Fury, I hoped to introduce

another edgy alternative to the standard male prototype. And I wasn’t alone, especially among lesbians. A partial list of

writers with their fingers on the pulse of lavender pulp includes Nikki Baker, Katherine V. Forrest, Jaye Maiman, J. M. Redmann,

Sandra Scoppettone, and Mary Wings. Lesbian mystery fiction became the hottest queer genre since the heyday of the coming-out

story.

But it didn’t happen in isolation—the whole mystery field has diversified in recent years. in addition to lesbians and gay

men, writers of color, both gay and straight, are contributing in increasing numbers. I believe mysteries are thriving these

days precisely because of this phenomenon. It’s certainly a factor in my love of the genre: as well as being accessible, lean,

and deliciously trashy, detective fiction almost always deals with marginal characters. Those of us outside the mainstream

can feel a keen affinity with the rebel P.I. bumping up against the status quo. Nell Fury, for example, is ambivalent about

law and order. She’s an agitator and an agent of change—albeit a pessimistic one—more than an enforcer of any rigid moral

code.

As the mystery field continues to expand, along with genre fiction in general, lesbian and gay characters are no longer invisible

and/or anathema. Yet progress continues to be slow. In writing about an outspoken lesbian private eye, I hope to validate

the spylike experience of outsiders and provide another kind of fictional voice. Fury’s lesbianism is at once matter-of-fact

and uniquely relevant. Like me, she is both a part of and separate from the lonely, gritty, big-city tradition of her literary

predecessors.

—ELIZABETH PINCUS

• Paquita Valdes in La Fille Aux Yeux d’Or/The Girl with the Golden Eyes by Honore de Balzac (1834)

• John Jasper in The Mystery of Edwin Drood by Charles Dickens (1870)

• Sparrow McCoy in Round the Fire Stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1909)

• Everard Mountjoy in Speedy Death by Gladys Mitchell (1929)

• Joel Cairo, Casper Gutman, and Wilmer in The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett (1930)

• Edward in The Murder of My Aunt by Richard Hull (1934)

• Peter Rigget in Flower for the Judge by Margery Allingham (1936)

• Anton Palook and Pavel Bunia in A Bullet in the Ballet by Caryl Brahms S.J. Simon (1937)

• Stephen Hawes in Serenade by James M. Cain (1937)

• Unidentified young man in Murder Among Friends by Elizabeth Ferrars (1946)

• Monica Brady and Ageline Small in Death of a Doll by Hilda Lawrence (1947)

• Charles Anthony Bruno in Strangers on a Train by Patricia Highsmith (1949)

— ANTHONY SLIDE

Homosexuality has been a part of science fiction as long as there has been a genre. From derogatory images to positive representation,

there have been thousands of science fiction books with gay and lesbian characters. During the seventies, science fiction

in general enjoyed a publishing boom. It was during this time that homosexuality became a prominent and permanent theme in

the science fiction universe. Below are just a handful of the many classics of the genre.

Einstein Intersection by Samuel R. Delaney (1967)

Moondust by Thomas Burnett Swann (1968)

left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. LeGuin (1969)

The Wild Boys by William S. Burroughs (1971)

The World Wreckers by Marion Zimner Bradley (1971)

Breakfast in Ruins by Michael Moorcock (1972)

The Book of Skulls by Robert Silverberg (1972)

The English Assassin by Michael Moorcock 1972)

The Man Who Folded Himself by David Gerrold (1973)

334 by Thomas M. Disch (1974)

Earthwreck! by Thomas N. Scortia (1974)

Walk to the End of the World by Suzy McKee Charnas (1974)

Dhalgren by Samuel R. Delany (1975)

The Female Man by Joanna Russ (1975)

The Heritage of Hastur by Marion Zimmer Bradley (1975)

Imperial Earth by Arthur C. Clarke (1975)

Arslan by M. J. Engh (1976)

The Woman on the Edge of Time by Marge Piercy (1976)

The Forbidden Tower by Marion Zimmer Bradley (1977)

Gateway by Frederick Pohl (1977)

Moonstar Odyssey by David Gerrold (1977)

Chrome by George Nader (1978)

A Different Light by Elizabeth A. Lynn (1978)

Kalki by Gore Vidal (1978)

The Wanderground by Sally M. Gearhart (1978)

Benefits by Zoe Fairbairns (1979)

Blade Runner by William S. Burroughs (1979)

The Dancers of Arun by Elizabeth A. Lynn (1979)

Mindsong by Joan Cox (1979)

On Wings of Song by Thomas M. Disch (1979)

Project Lambda by Pell Wells (1979)

Retreat: As It Was! by Donna J. Young (1979)

—DON ROMESBURG

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

The Minneapolis-based Womyn’s Braille Press, founded by six blind lesbians in 1980, is the only organization in the United

States dedicated to making feminist and lesbian literature available on tape and in Braille. The volunteer-run organization

currently offers more than 800 book titles, periodicals, and pamphlets to its readership.

There has been a great deal written lately heralding the coming of age of gay and lesbian writing. Although the “mainstream”

is just now beginning to notice the market for this material, women’s presses and women’s bookstores have been hard at work

for the last twenty-five years producing and selling books that feminists and lesbians want to read.

Sasha Alyson, founder of Alyson Publications. (Robert Giard)

As former Spinsters Book Company publisher Sherry Thomas noted in Publishers Weekly, “This wave of the women’s movement—the one that began in the early 1970s—was organized in its earliest days around writing.

There was a whole network of newspapers, magazines, small publishers, bookstores and printing presses who would print our

hooks (when the commercial printers refused this work). I can’t find any other movement for social or cultural change in the

country that’s been as print-based. Publishing is integral to how women began to see themselves.”

“MAINSTREAM” QUEER AUTHORS WHO GOT THEIR START WITH THE GAY AND FEMINIST PRESSES

Dorothy Allison, National Book Award nominee (Firebrand Press)

Rita Mae Brown, novelist (Daughters, Inc.)

Larry Duplechan, novelist (Alyson Press)

Joseph Hansen, prolific mystery writer (One, Inc.)

Audre Lorde, poet and novelist (Spinsters)

Michael Nava, mystery writer (Alyson Press)

John Preston, erotic novelist (Alyson Press)

Sarah Schulman, novelist (Naiad)

One of the central events in this movement was the 1976 Women in Print Movement Conference. The conference highlighted the

aspirations and concerns of those women who had plunged into the third wave of feminism with enthusiasm, dedication, and a

large dose of idealism, convinced that if women owned an independent press network, our words could not be suppressed.

In fact, the 1970s did see a great revival of feminism, and the vision of that time has given rise to a network of feminist

bookstores (doing over $35 million in business annually), over forty woolen-owned publishing companies, and magazines and

newspapers too numerous to count. We succeeded in making lesbian and feminist concerns visible.

Becoming Visible

While psychological treatises of lesbians or novels with lesbian characters have appeared in mainstream publishing for years,

they generally presented a rather bleak picture of lesbian life, with suicides, or women seeing their true path and returning

to men as the probable outcomes. No tough dykes here; only passionate yet anguished women who struggled valiantly to overcome

their attraction to other women.

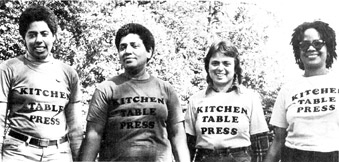

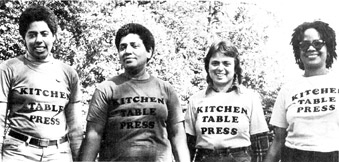

Members of kitchen, Table/Women of Color Press (1981) included (from left to right) Barbara Smith, Audre Lorde, Cherríe Moraga,

and hattie gossett. (©JEB)

Then came the revolution, at least it felt like that to lesbians who had remained securely in the closet. Lesbian/Woman by Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon appeared, lavender cover and all, touted as “Essential reading for all women!” by Bantam Books

in 1972. And then Lesbian Nation, with a smiling, jeans-jacketed Jill Johnston proclaiming “until all women are lesbians, there will be no true political

revolution,” published by Simon and Schuster, 1973.

“In the beginning it required small presses, gay newspapers and magazines, and mainstream houses all working together to launch

gay and lesbian literature. As far as women’s literature is concerned, the small presses have done virtually all of the work.

Gay male fiction became more experimental in the 1980s. And presses like SeaHorse, Alyson, and Crossing Press brought out

new writers whom the mainstream would not touch: Robert Gluck, Dennis Cooper, Brad Gooch—some of whom have since become mainstream.

I still question the mainstream’s ability to consistently find the cutting edge of gay and lesbian literature.”

“In the beginning it required small presses, gay newspapers and magazines, and mainstream houses all working together to launch

gay and lesbian literature. As far as women’s literature is concerned, the small presses have done virtually all of the work.

Gay male fiction became more experimental in the 1980s. And presses like SeaHorse, Alyson, and Crossing Press brought out

new writers whom the mainstream would not touch: Robert Gluck, Dennis Cooper, Brad Gooch—some of whom have since become mainstream.

I still question the mainstream’s ability to consistently find the cutting edge of gay and lesbian literature.”

FELICE PICANO, A MEMBER OF THE VIOLET QUILL, A GAY MALE WRITERS’ SALON FROM THE LATE SEVENTIES AND EARLY EIGHTIES

At this same time, the first of the feminist/lesbian presses were starting up, like Diana Press, Daughters, Inc., the Women’s

Press Collective, the Persephone Press, and others who believed that women’s/lesbian voices would not be well-represented,

if at all, by the mainstream, and that part of our empowerment was to determine what was published.

Over the past twenty years, the mainstream presses have continued to publish a few books here and there featuring lesbian

protagonists, like Don Juan in the Village, or After Delores. However, the number of feminist/lesbian presses has grown to over forty in the United States, publishing hundreds of lesbian

hooks a year, making it a challenge for all the dedicated readers to keep up. The 1990s have become the years of the queers,

and mainstream publishers have “discovered” a new and literate market. Whether or not this fad continues, it is fair to assume

that at some point women will once again have to rely on lesbian/feminist presses to supple the books they really want to

read.

—BETH DINGMAN

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

In 1976, the first Women-In-Print conference was attended by one-hundred and twenty-seven women, representing seventy-three

groups—feminist newspapers, journals/magazines, bookstores, book publishers, Printers and distributors. While the conference

was a watershed for the print movement, The New York Times Magazine article offered this sensationalist description of the event: The women “gathered together for the first time to chart their

course and define their ultimate goal—not to become a unified underground women’s press, but actually to lead a feminist takeover

of the nation’s media. The secret convention was held at a Campfire Girls camp near Omaha, Nebraska. They were and are, serious.

The only question is how they expect to succeed.”

The women’s movement was reborn in the 1970s, and along with it cane an avalanche of journals, newspapers, pamphlets, and books

teaching women to take control of their bodies, their cars, their relationships, and their culture.

At the forefront of that movement was Daughters, Inc., founded by June Arnold and Parke Bowman in 1973 in Plainfield, Vermont.

Working out of an old farmhouse, June and Parke, with the assistance of Bertha Harris, Jane Myers, Sane Stockwell, Martha

Yates, Mary Dawson and others, made a lasting contribution to women’s literature. Specializing in feminist and lesbian fiction,

by 1978 Daughters had twenty-four titles in print, no small feat in the days when many printers would not handle lesbian material.

Daughter’s best known book was Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle, which became an instant success when it sold more than 70,000 copies. (Rubyfruit was later bought by the mass market publisher Bantam. where it continued to sell hotly for mare years.)

Daughters was unique in other ways as well. “So far, every novel from Daughters has been without literary precedent,” wrote

Polly Joan and Andrea Chesman in The Guide to Women’s Publishing. Books published by Daughters included The Cook and the Carpenter by June Arnold, Confessions of a Cherubino by Bertha Harris, and Angel Dance by M. F. Beal, as well as works by Joanna Russ, Monique Wittig, Elana Nachman, Blanche Boyd, and Charlotte Bunch. June dreamed

of “building a feminist literature in which the power of women’s words can reshape the language and the culture in which they

are written.” She and Parke were committed to making women culturally and economically independent, and were influential in

organizing the first Women-In-Print conference, a watershed event in the feminist print movement, in 1976.

FEMINIST AND GAY MALE PRESSES STILL GOING STRONG TODAY

Feminist Press, New York (1970)

Naiad Press, Tallahassee, FL (1973)

Seal Press, Seattle, WA (1975)

Down There Press, San Francisco, CA (1975)

Volcano Press, Volcano, CA (1976)

New Victoria Publishers, Norwich, VT (1977)

Gay Sunshine Press, San Francisco, CA (1977)

Spinsters, Ink, Duluth, MI (1978)

Cleis Press, Pittsburgh, PA (1980)

Alyson Press, Boston, MA (1980)

Mother Courage, Racine, WI (1981)

Kitchen Table Women of Color Press, New York (1981)

Aunt Lute, San Francisco, CA (1982)

Papier Maché, Watsonville, CA (1984)

Firebrand Books, Ithaca, NY (1984)

Clothespin Fever Press, Los Angeles, CA (1985)

Calyx Press, Corvalis, OR (1985)

Eighth Mountain Press, Portland, OR (1985)

Paradigm Publishing, San Diego, CA (1989)

Rising Tide Books, Huntington, NY (1991)

Thirdside Press, Chicago, IL (1991)

Madwomen Press, Northboro, MA (1991)

—BETH DINGMAN

June died in 1985. And although Daughters died with her, the legacy she left continues in the more than forty feminist publishers

alive and well today.

—BETH DINGMAN

The follow is a statement by Barbara Smith and Joseph Beam at the Second National Black Writers Conference at Medgar Evers College, New York, in 1998. It appeared in the journal BLACK/OUT in the fall of 1988, and was signed by many of the most prominent Black gay and lesbian writers of the 1980s.

We are Black lesbian and gay writers who are taking the opportunity of The Second National Black Writers Conference to go on

record. We are well aware that despite our commitment to exploring gender roles and to challenging sexual, racial, and class

oppression, work that has been essential to transforming the practice of African American literature in this era, the Black

literary establishment systematically chooses to exclude us from the range of its activities. These include participation

in conferences, invitations to submit work to journals, anthologies, serious and non-homophobic criticism of writing, positive

depictions of lesbian and gay characters, inclusion in Black studies course curricula, and all levels of formal and informal

mentoring and support. If we are sometimes included in token numbers, it is often amid heterosexist protest and homophobic

attacks. Because we function with integrity, refuse to be closeted, and address lesbian and gay oppression as a political

issue, our lives and work are made invisible.

In spite of effort to ghettoize and exclude us, we are part of a long and proud Black lesbian and gay literary tradition.

The Harlem Renaissance could not have occurred if it had not been for its Black gay participants, among them: Countee Cullen,

Langston Hughes, Wallace Thurman, Alain Locke, and R. Bruce Nugent. Historically, Black lesbian writers have been less easily

identifiable, but recent research has documented that Alice Dunbar Nelson, Agelina Weld Grimke, and Lorraine Hansberry are

also members of this tradition. James Baldwin, undoubtedly the best known African American writer, gave us many positive depictions

of gay male relationships including those between Black men. Baldwin opened up new literary territory for an entire generation

and served as a special role model for those of us who are lesbian and gay. Yet, since his death in December 1987, there has

been a concerted effort to ignore the fact he was homosexual. The acknowledgment of our work as Black lesbian and gay writers

necessitates a major revision of a currently homophobic and inaccurate Black literary history.

Black lesbian and gay men have always been here, as contributing family members in this country and before that in the Motherland

of Africa; but, we have been frequently attacked as traitors to the race. Our existence is not what threatens the future of

the race: instead the Black liberation struggle is imperiled by homophobic exclusion and emotional, physical, and sexual violence

aimed at those of us who are lesbian and gay. Yet, we are alive, well, and living with dignity, carrying out the challenge

of our difficult and much needed work.

Signed by:Joseph Beam, Becky Birtha, Julie Blackwomon, Cheryl Clarke, Anita Cornwell, Doris Davenport, Alexis de Veaux, Jewelle Gomez,

Craig G. Harris, Essex Hemphill, Issac Jackson, Cary Alan Johnson, Audre Lorde, Pat Parker, Michelle Parkerson, Philip Robinson,

Assoto Saint, Barbara Smith, Lamont Steptoe, Evelyn C. White

In my reading of lesbian novels and short stories, I have encountered many attempts at The Love Scene, from abysmal to arousing.

In general, they fall into four categories, which, for fun, I’ve classified as you might for a subspecies of plants: Erotica dottica, Erotica botanica, Erotica naiad pressica, and Erotica explicita.

Let me explain.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

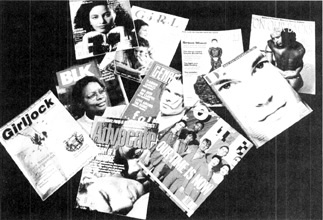

In 1994 there were sixty-five gay and lesbian newspapers in the United States, with an estimated combined readership of three

million, according to the Queer Resources Directory (Internet). In addition, there are more than a dozen monthly and bimonthly

magazines aimed at the gay and lesbian audience.

Erotica dottica. This species originates from the days when sex was not actually described at all, and the advent of anything other than passionate

friendship or a romantic kiss was hinted at by the means of a coy “…” at the end of the sentence, or three asterisks in the

middle of a page. In that blank space, the imaginations of lesbians could go wild if they pleased. Today, this type of love

scene (or lack of it) is regarded as a cop-out, or a denial of our sexuality, or self-censorship. Instead, the lead-up to

the dot-dot-dot has become longer, allowing the women to get somewhere (usually below the belt but not right in) before they

have to close the curtains on their lovemaking. This is the “less is more” theory of lesbian love scenes.

Of course, some authors can’t do Erotica dottica very well at all. “Frances leaned over and kissed Caroline on the mouth,” for example, is not the sort of sentence that should

lead to a dot-dot-dot. This is selling the reader short. At the very least, Frances should continue kissing Caroline’s longing

nipples, trembling stomach, and be decisively making her way farther down to the aching warm wetness before any clots intrude.

Erotica botanica (rare). As a friend of mine says: “No petals, please!” Erotica botanica is the lesbian love scene where we are reminded constantly of our connection with the natural world and therefore the naturalness

of our sexuality. Great in theory, but often overstated in practice: “Karen parted the dewy petals and sought out the rose

bud within. Her fingers traced the ferny under-growth to the wet cave of Bertha’s desire …” is the sort of cosmic bush walk

we usually get. All too often, the sensuality of nature is stuck on to lesbian bodies with the subtlety of metallic cones

on to Madonna!

Erotica botanica is harder to find these days, as Erotica naiad pressica and Erotica explicita become more popular. Nowadays, we can name the rose, and most authors, running out of fresh fruit, flora, and fauna, have

gratefully moved on to less limiting and noire direct imagery. The moist velvet flowers of lesbiana are less likely to he

found pressed between the covers of our favorite novels.

Erotica naiad pressica. These love scenes are the most common variety in lesbian light novels. They sneak into whodunits, historical romances, mysteries,

love stories, and detective yarns.

This is not, however, gratuitous sex. The characters are always on their way to a perfect orgasm (or two), but they stay in

character while they come.

Erotica naiad pressica uses a join-the-dots description of sex to enable the author to describe even detail without actually using the Rude Words.

This species of “soft core” love scenes usually indulges in one or two pages of stroking tongues, soft damp thighs, wet longing,

eagerly sucked nipples, “feasting,” arching bodies, and cries of passion before climaxing in a paragraph of orgasmic ecstasy.

Watch out for chapters 5 and 10.

Author and lesbian vampire creator Jewelle Gomez relaxes in Harlem in 1992 (Val Wilmer)

Isn’t this Erotica explicita? No way! The effect aimed for is sensuous rather than straight-up sexy. There’s a lot of bare skin, but no clitorises. Lots

of orgasms (or, rather, shuddering releases) but no dildos or vibrators. In Erotica naiad pressica, you can slide urgent fingers into the exploding wetness, but you can’t thrust hands up cunts. It’s just not Nice!

Erotica explicita. Who cares about plot and character development? Let’s fuck, baby!

Like all styles of love scenes, explicit sex can be written well or written appallingly. One book I’ve read lately (Province Town) had enough “throbbing wet holes” to make a geothermal wonderland, and enough “dripping hot pussies” to fill a cattery!

At least Erotica explicita gets around all those problems about what to call It. “Her clit was enflamed; her cunt was throbbing,” Jewelle Gomez tells

us in “White Flowers” (Serious Pleasure). Get the picture? In Erotica explicita you’re allowed to say ass, fuck, fist, crack, slit, and clit. In fact, you should say them a lot. Everything is slippery

or dripping, never silky. Hard is a great Erotica explicita word. You’re allowed to be Politically Incorrect, too. That’s almost an essential part of the genre.

You’ll find most Erotica explicita in short stories or novels that might as well be a series of short stories—the plot is merely a rickety bridge to the next

throbbing hole in which the reader can wallow. Great reading for a wet weekend!

—BERYL PEARS

The “Lammys” began in 1988 when the Lamba Book Report, a gay and lesbian literary review, decided that lesbian and gay books deserved their own awards and commendations. During

the first year, the ceremonies were held in Washington, D.C., with Armistead Maupin (Tales of the City) as emcee. Since that time the award has gone to some of the most honored books in the nation.

Lesbian Nonfiction

Lesbian Ethics by Sarah Hoagland (1988)

Really Reading Gertrude Stein edited by Judy Grahn (1989)

The Safe Sea of Women by Bonne Zimmerman (1990)

Cancer in Two Voices by Sandra Butler and Barbara Rosenblum (1991)

Eleanor Roosevelt by Blanche Wiesen Cook (1992)

Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold by Elizabeth Kennedy and Madeline Davis (1993, Lesbian Studies)

Gay Men’s Nonfiction

Borrowed Time by Paul Monette (1988)

In Search of Gay America by Neil Miller (1989)

Coming Out under Fire by Alan Berube (1990)

Zuni Man-Woman by Will Roscoe (1991)

Becoming a Man by Paul Monette (1992)

Conduct Unbecoming by Randy Shilts (1993, Gay Men’s Studies)

Lesbian Fiction

Trash by Dorothy Allison (1988)

The Bar Stories by Nisa Donnelly (1989)

Out of Time by Paula Martinac (1990)

Revolution of Little Girls by Blanche McCrary Boyd (1991) and Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez (1991, tie)

Running Fiercely Toward a High Thin Sound by Judith Katz (1992)

Written on the Body by Jeanette Winterson (1993)

Gay Men’s Fiction

The Beautiful Room Is Empty by Edmund White (1988)

Eighty-Sixed by David B. Feinberg (1989)

The Body and Its Dangers by Allen Barnett (1990)

What the Dead Remember by Harlan Greene (1991)

Let the Dead Bury Their Dead by Randall Kenan (1992)

Living Upstairs by Joseph Hansen (1993)

AIDS (A Special Category)

Borrowed Time by Paul Monette (1988)

Reports from the Holocaust by Larry Kramer (1989)

The Way We Live Now edited by Elizabeth Osbourn (1990)

(no winners, 1991–1993)

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Time Warner gave up plans to publish a mainstream magazine aimed at gays and lisbians—because the publisher thought it wouldn’t

sell. “It’s difficult to imagine taking on a magazine that would not make several million dollars annually in profits,.”the

Time, Inc., Venture president told The New York Times in 1994.

Lesbian Mystery

(no winnner, 1988)

The Beverly Malibu by Katherine V. Forrest (1989)

Gaudi Afternoon by Barbara Wilson (1990) and

Ninth Life by Lauren Wright Douglas (1990, tie)

Murder by Tradition by Katherine V. Forrest (1991)

Two Bit Tango by Elizabeth Pincus (1992) and

Crazy for Loving by Jaye Maiman (1992, tie)

Divine Victim by Mary Wings (1993)

Gay Men’s Mystery

Golden Boy by Michael Nava (1988)

Simple Suburban Murder by Mark Zubro (1989)

Howtown by Michael Nava (1990)

Country of Old Men: The List Dave Brandsetter Mystery by Joseph Hansen (1991)

The Hidden Law by Michael Nava (1992)

Catilina’s Riddle by Steven Saylor (1993)