What is gay history? Is it just when we discover that some-one from the past had a long-term intimate relationship with someone

of the same sex? Or is gay history simply the history of self-identified homosexuals? What do we make of Native American cultures

that did not have concepts of homosexuality vs. heterosexuality? How do alternative interpretations of gender and sexuality

fit into the picture?

Clear answers are hard to come by. Discovering that someone was intimate with others of the same sex does add to our history,

but it does not make him or her “gay.” “Gay” and “lesbian,” like the word “homosexual.” are terms that are fixed in a specific

historical era, namely the 20th century. Unlike other minorities, for whom finding oneself in history is simply a matter of

finding out a person’s race or religion, gay people have to put together the pieces of a complex puzzle, often using suspicion

and loose associations to discover the hidden lineage that is a part of our history.

But the broader questions of what constitutes gay history and who decides it are more difficult to answer. In a sense, everything

we do as lovers of our own sex is historical. What we remember about events and how we tell the stories of those events influences

the very nature of history. In addition, everything that is done by others in reaction to same-sex intimacy, by politicians,

religious leaders, and medical professionals, shapes the way that society views sexuality.

J.C. Leyendecker, the commercial artist who came up with the Arrow Collar Man in the early twentieth century, was gay. His

inspiration and model, Charles Beach, was his lover.

Gender can also be considered a part of gay history. Homosexual behavior, by both men and women, has often been characterized

in the past as a gender transgression. In other words, gay men act “womanish” or “effeminate,” while lesbians act “masculine”

or “mannish.” The ways a society defines gender affect the ways it defines sexuality. But what should we make of women who

passed as men, drag queens, and Native American berdache? Are they part of a transgendered history or gay history? Or are

the two histories inexorably intertwined?

In this chapter, we do not attempt to fully answer these questions. What we have done is create a mosaic of some of the aspects

of American history we feel we can claim. From homosexual gathering places to political organizations, and from same-sex intimacy

in the Old West to the medical “cures” that doctors have inflicted on queer people for over a century, one thing is certain:

Gay people have a heritage and a history that is as multifaceted as our diverse contemporary culture.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

The first recorded evidence of homosexuality is found in Mesopotamia circa 3000 B.C., where artifacts depict men having sex with other men.

When looking into the past, it’s hard to say exactly who was or was not gay or lesbian. Depending on the era, culture, class,

race, and gender of people, certain activities were considered within the realm of “normalcy,” while other activities were

considered “deviant.” For example, before the late nineteenth century in the United States, concepts of same-sex love did

not carry the same stigma they do today. What we can do is look at those who have loved their own sex throughout history,

and celebrate that love, in whatever form it took. We don’t necessarily have to label it as “gay.” Here are some famous names

from U.S. history who have been lovers of their own sex:

Horotio Alger (1832–1899), American success parable writer

Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906), suffragist and women’s activist

Josephine Baker (1906–1975), jazz singer

James Baldwin (1924–1987), novelist

Djuna Barnes (1892–1982), modernist writer

Ruth Benedict (1887–1948), anthropologist and suffragist

Gladys Bentley (1907–1960), blues performer

James Buchanan (1791–1868), fifteenth President

Truman Capote (1924–1984), writer and wit

Willa Cather (1873–1917), novelist

Jane Chambers (1937–1983), playwright

Montgomery Clift (1920–1966), actor

Roy Cohn (1927–1986), Joseph McCarthy’s lawyer

Hart Crane (1899–1932), poet

George Cukor (1899–1983), Hollywood director

Countee Cullen (1903–1946). Harlem Renaissance poet

James Dean (1931–1955), American icon and screen idol

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886), poet

Errol Flynn (1909–1989), swashbuckling actor

Stephen Foster (1826–1864), songwriter

Paul Goodman (1911–1972), progressive writer

Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804), first secretary of the Treasury

Lorraine Hansbuno (1930–1965), playwright

J. Edgar Hoover (1898–1972), FBI director

Rock Hudson (1925–1985). Hollywood heartthrob

Langston Hughes (1902–1967), Harlem Renaissance poet

Alberta Hunter (1898–1984), blues great

Christopher Isherwood (1904–1986), novelist

William Rufus King (1786–1853), pierce’s vice president

Liberace (1919–1987), flamboyant showman and pianist

Alain Locke (1886–1954), academic and writer

“Moms” Mabley (1897–1975), comic great

Margaret Mead (1901–1978), anthropologist

Herman Melville (1819–1891), novelist

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892–1980), poet

Ramon Novarro (1899–1968), silent movie actor

Cole Porter (1893–1964), songwriter

Ma Rainey (1889–1939), blues performer

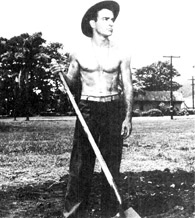

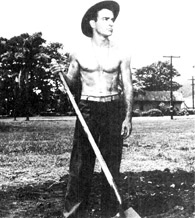

That Montgomery Clift was a lover of his own sex is such an open Hollywood secret that calling someone “today’s Montgomery

Clift” in gossip columns is another way of saving an actor is gay. Here, a bare-chested Clift costarred in From Here to Eternity

in 1953 (courtesy of Columbia Pictures)

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

In 1566, the Spanish military executed a Frenchman for homosexuality in St. Augustine, Florida. This is the earliest known

case of punishment of homosexual activity in America.

Eleanor Roosevelt (1884–1962), activist and politician

Bayard Rustin (1912–1987), civil rights organizer and activist

Bessie Smith (1894–1937), blues icon

Gertrude Stein (1874–1946), writer

“Big Bill” Tilden (1893–1953), tennis star

Rudolph Valentino (1895–1926), screen idol

Andy Warhol (1928–1987), pop artist

James Whale (1896–1957), classic horror film director

Walt Whitman (1819–1892), poet

Tennessee Williams (1911–1983), playwright

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

On May 24, 1610, the state of Virginia created the first sodomy law in America. It called for the death penalty.

For the past decade, Jim Wilke has been doing pioneering research into the lives of gay men who were frontiersmen in the United

States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These were men who went west, either from the desire for

adventure or the need to survive, men who worked the ranches, farmed the fields, or joined the army in search of independence

and a different way of living from that offered in the cities of the East.

While today we use the term “gay” to describe these men, research has shown that they had no such language to describe themselves

until sometime after the Civil War. Nonetheless, these men lived together and loved together, with a commitment beyond any

notion of “situational homosexuality.”

While filming Red River (1955), John Wayne’s famous demand about Montgomery Clift—that director Howard Hawks “get that faggot off my set”—underscored

a common belief that homosexuality had no place in the rough and tumble American West. Recent research, however, indicates

that homosexuality was not only common, but may actually have thrived in the frontier.

Moreover, popular folklore which does acknowledge same-sex interactions in the frontier assumes that “situational homosexuality,”

the desire for sexual contact with members of the same sex in the absence of opposite sex partners, is the primary motivational

force behind any existing homosexuality. Yet this does not account for urban homosexuality in Western cities, or homosexuality

among Western women. It appears more likely that Westerners responded to a multitude of internal and external conditions that

allowed them to alternately discover or redefine their emotional and sexual desire.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

According to historian Jonathan Katz in his book Gay American History, from the time that Alabama senator William Rufus De Vane King (a fifty-seven-year-old bachelor) met Pennsylvania senator

James Buchanan in 1834, until King’s appointment as U.S. minister to France, the two were inseparable. Their intimate relationship

caused barbed comments in Washington. Andrew Jackson called king “Miss Nancy,” and in a private letter in 1844. Aaron Brown

referred to King as Buchanan’s “better half” and (in jest) referred to Buchanan and King’s “divorce.”

Historian Hubert Bancroft noted that during the 1850s California Gold Rush. “the requirements of mining life favored partnership

… sacred like the marriage bonds, as illustrated by the softening of ‘partner’ into the familiar ‘pard.’” In 1914., migrant

California fieldworkers were recorded to have not only justified but idealized homosexually monogamous relationships. Larger

groups of men in isolated raining, logging. or railroad construction camps appear to have been more gregarious. “Restlessness

among the crew” of one Western mining camp brought over half of the camps “brawny, ultra-masculine” men to seek sexual “relief”

with each other. Similar conditions existed in Civilian Conservation Corp camps in Texas iii the 1930s and a highway construction

camp in California in the early 1950s.

Western cities such as San Francisco, Denver, Salt lake City, and Chicago enjoyed highly developed homosexual urban subcultures

which followed patterns established in Eastern cities. Several different “circles” within a city reflected divergent interests

and pursuits. All provided a network of mutual support to those fortunate enough to be accepted into them. A San Francisco

homosexual man wrote in 1911 that life could he “hard, for many crushing, but it is extremely interesting, and I am glad to

have been given the opportunity to have lived it.”

In the 1890s, a Colorado professor wrote that Denver’s homosexual population included “fiye musicians, three teachers, three

art dealers, one minister, one judge, two actors, one florist. and one woman’s tailor.” In California, an 1887 land boom led

San Diego to build an elaborate Victorian house as an inducement for musician Jesse Owens Sharard and his male partner to

move there and lend the city an air of cosmopolitan refinement. Similar social and artistic soirees were held in the 1880s

in Southern California at the home of two San Juan Capistrano men.

There was probably no occupation in the West that did not have lesbian and gay participants. William Breakeridge worked as

a Union Pacific brakeman before becoming a deputy sheriff at Tombstone, Arizona ’Territory, where he was known and accepted

by many of the mining town’s community. Stagecoach driver Charlie Parkhurst was discovered to be a woman only after her death

in 1879, a fact which made much newspaper copy. The San Francisco Call remarked that “No doubt he was not like other men, indeed, it was generally said among his acquaintances that he was a hermaphrodite”

and that “the discoveries of the successful concealment for protracted periods of the female sex are not infrequent.” Oregon

native Lucile Hart, a Stanford medical school graduate, is noted by historian Jonathan Katz to have dressed as a man in order

to practice medicine and marry the woman she loved. Her own doctor wrote that “if society will but leave her alone, she will

fill her niche in the world and leave it better for her bravery.”

In the 1800s, sodomy laws were found in all states and territories, but were selectively enforced. In 1873, Lawrence G. Murphy,

a civilian post trader at Fort Stanton, New Mexico, was charged with a “most unnatural” relationship with a local official

in an effort to cancel his military contract. In El Paso, Texas, an 1896 charge of sodomy against Marcelo Alviar brought with

it a bond set at $500, the same amount as for murder. The prohibitively expensive bond was punitive, and virtually guaranteed

jail time or the loss of the defendant’s life savings or property. This system of select enforcement was similarly applied

to gambling houses, saloons, and brothels. Male prostitution existed in varying degrees, from an “elegantly furnished” 1882

Midwestern brothel to a particularly clandestine male street prostitution ring in San Francisco in 1902. Homosexuality in

Western prisons was so common that in 1877, San Quentin director Dr. J.E. Pellham launched a crusade against it, advising

solitary confinement as therapy.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Train robber Bill Miner, the notorious “Grey Fox” who was “said to be a sodomite” by Pinkerton’s Detective Agency, preferred

as accomplices young men he met during periodic stays in prison.

Among Westerners there existed a gentleman’s agreement that arose from the need to survive in the frontier. One part of this

agreement was mutual respect, allowing one “the right to live the life and go the gait which seemed most pleasing to himself.”

Historian David Dary has written that cowboys “sought to live lives that were free from falsehood and hypocrisy.” This frontier

code of conduct allowed many people to enjoy open relation-ships that would have otherwise not been possible.

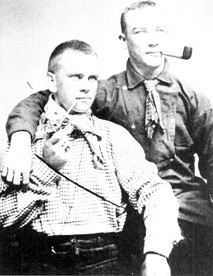

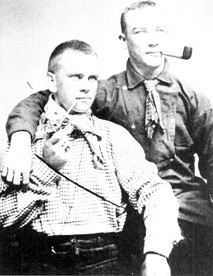

Two cowboys from the late nineteenth century pose in a manner traditionally used for portraits of husbands and wires. (©Jim

Wilke)

On the open range, cowboys often developed strong and loyal relation-ships with each other. The dangers of stampedes and general

rigors of the trail required absolute cooperation: a cowboy who could not be relied on found himself outcast. Loyalty was

“one of the most notable characteristics of the cowboy.” and devotion to one’s “pard” was highly regarded. The cow-boy expression

that one was “in love.” with someone could sometimes be taken literally. The Texas Livestock Journal remarked in 1882 that “if the inner history of friendships among the rough, and perhaps untutored cowboys could be written,

it would he quite as unselfish and romantic as that as of Damon and [Patroclus].”

Many circumstances contributed to personal closeness on the ranch and trail. Cowboys frequently bedded in pairs with their

“bunkie,” and a ranch bunkhouse was occasionally called a “ram pasture.” Many cowboys engaged in “mutual solace.” a tender,

expressive, and euphemistic terra for sexual relations. Vulgar and explicit “ugly songs” describing phallic size, virility,

and sodomy were sung around campfires. In 1920s Nevada, the “sixtynine” sexual position was common enough among cowboys to

warrant its own euphemism, “Swanson neuf.”

Gay cowboys continue to be an intrinsic part of the West. In 1957, two Texas cowboys visiting the Mayflower Bar, an Oklahoma

City gay bar, described their life as one where there are generally two or three gay cowboys to a ranch, who quietly recognize

each other, keeping their identity a secret from the others. While many working horsemen and horsewomen maintain a quiet reticence

associated with the broader aspects of ranching culture, the modern lesbian and gay civil rights movement has brought a growing

number of openly gay and lesbian ranchers, as well as the creation of the International Gay Rodeo Association, with chapters

around the United States and Canada.

—JIM WILKE

Trinidad restauranteur Charles “Frenchey” Vobaugh was a woman who passed as a man and, along with “his” wife, assumed the outward

appearance of a heterosexual couple in order to remain married for thirty years. Colorado newspapers were full of successful

lesbian and gay elopements. In 1889, the town of Emma was “rent from center to circumference” over the “sensation-al love

affair between Miss Clara Dietrich, postmistress and general storekeeper, and Miss Ora Chatfield.” letters written between

them caused the Denver papers to remark that the “love that existed between the two par-ties was of no ephemeral nature, but

as strong as that of a strong man and his sweetheart.” Despite attempts to separate them, the “lady lovers” successfully eloped.

“If the case ever comes into court,” wrote the Denver Times, “from a scientific standpoint alone it will attract wide-spread

attention.” In 1898, Boulder teamster W. H. Billings left his wife and sold his horses in order to runaway with Charles Edwards,

a saloon entertainer who played banjo and performed acrobatics. A Denver paper reported that Billings was “not happy unless

he was trailing around the streets with Edwards” and that “if his home had any charms for him, said his wife, they had fled

and all on account of a banjo player.”

—JIM WILKE

Reviews of’ military accounts during the frontier era reveal few instances of soldiers being prosecuted for sodomy. This ’

as not because sodomy was rarely practiced; the military brass chose to disguise such situations rather than admit that they

occurred within a military post. This allowed the military to prevent such charges from going on the public record, reflecting

both contemporary prejudice and reticence upon the part of the military to acknowledge that such situations existed. In the

1890s, an infantryman was charged in private military correspondence with the “sin of Oscar Wilde”; however, he was publicly

drummed out of the 24 Colored Infantry on unrelated charges.

Only when sodomy became publicly evident did the military find it necessary to enact an equally public response. The 1878

death of a Seventh Cavalry laundress caused a sensation that was telegraphed from New York to San Francisco. After ten years

of loyal service with the Cavalry, Mrs. Corporal Noonan was discovered to be a man. Because she was a popular midwife, good

cook, and nurse. the exposure of “her” identity revealed an extraordinary series of homosexual relationships among cavalrymen

on one of the most well-known military posts, George Custer’s Seventh Cavalry.

“She” was a New Mexican teamster that Seventh Cavalry Captain Lewis McClean Hamilton met on the streets of Leavenworth City,

Kansas, in 1868. “Their recognition was mutual,” a confidant later recalled. In order to have a relationship, Captain Hamilton

brought her into his employ under the guise of a military laundress, appointing “her” to his company, Company A. Military

laundresses served at the captain’s prerogative, and the bullwhacker-turned-laundress faithfully followed Hamilton until his

death eight months later in the Battle of Washita in November 1868.

After a hunt, (from left to right) Bloody Knife, General Custer, John Noonan, and Ludlow posed for a picture. Noonan was married

to another man, who was passing as a woman. Mrs. Noonan washed Mrs. Custer’s clothes. (South Dakota Historical Society, State

Archives)

The bullet that pierced Hamilton’s heart that morning left behind an unusual widow. Remarkably, “she” remained in military

employ. Her resolve in the matter is admirable, for in addition to developing a growing reputation as a superb laundress,

she became known as a sometime nurse, emergency midwife, excellent cook, and tailor. Elizabeth Bacon Custer, wife of Lieutenant

General George Custer, employed her in the early 1870s. She recalled that “when she brought the linen home, it was fluted

and frilled so daintily that I considered her a treasure. She always came at night, and when I went out to pay her she was

very shy, and kept a veil pinned about the lower part of her face.” All of these domestic skills contributed financially to

the laundress’s existing income and indicate that she was a very strong-willed and resourceful person. She was also very popular

within the social worlds of military society. Mrs. Custer remembered her presence at military halls, wheeling about the barracks

floor dressed in “pink tarletan and false curls, and not withstanding her height and colossal anatomy, she has constant partners.”

Following Hamilton’s death, the popular widow eventually married three more times. While the first two husbands deserted the

Cavalry, her third and final marriage was successful and endured. With the transfer of the Seventh Cavalry to Fort Abraham

Lincoln, Dakota Territory, in 1873, came Private John Noonan, Company L. His commitment to professional soldiering, an “excellent

character,” and subsequent rise from private to sergeant showed Noonan to have been a superb soldier. His reputation was further

enhanced by assignments as orderly to the Custer command. In about 1874, “Colonel Tom’s own man,” as Mrs. Custer referred

to Noonan, possessed sufficient merit to officially marry Mrs. Noonan. Noonan reenlisted in January 1877, and by the following

year had again worked his way up to the rank of corporal.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, late-nineteenth- and early twentieth-century physician and feminist, was called by her male enemies

“the most distinguished sexual invert in the United States.” She was actually, not a lesbian, but an open cross-dresser. A

qualified physician, she had to force her service on an unwilling federal government during the Civil War; she eventually

won a Congressional Medal of Honor for her work. She also became the first woman in the United States permitted by, Congress

to dress in male attire. Eventually, the militant Dr. Walker moved out of step with her sister feminists because her taste

in dress offended them. It was one thing to wear the men’s trousers—but it was quite another to go whole bop as did Mary Walker.

She affected shirt, bow tie, jacket, top hat, and cane.

When his wife died on October 30, 1878, Corporal Noonan was on escort duty over three hundred miles away. The success of her

disguise had been thorough; the laundress who volunteered to prepare the body for burial was quite surprised, emerging from

her duties shouting, “She’s got balls as big as a bull, she’s a man!” The news rapidly spread and the surrounding community

was “plunged into a pleasurable curiosity to know the particulars.” News of the “unnatural union and apparel” was telegraphed

to newspapers from coast to coast. The accuracy of these sensational stories was confirmed by the official report of Post

Surgeon W. D. Wolverton, who “found the body to be that of a fully developed male in all that makes the difference in sex,

without any abnormal condition that would cause a doubt on the subject.”

The enormous public attention paid to this matter led not only to Noonan’s dishonorable discharge, but because of the public

nature of his trespass against social convention and military “honor,” it exacted an equally public punishment. Commanding

Officer Sturgis wrote on November 23. 1878, that “if there is any law by which this man could he sent to the penitentiary

I would respectfully suggest that it be called into requisition in his case.” Military brass concurred and Sturgis was “instructed

to bring the case to attention of the U.S. District Attorney.” However, Noonan committed suicide before prosecution could

continue. He died in the Company stables at the age of thirty on November 30, 1878. His death was noted by a local newspaper

to have “relieved the regiment of the odium which the man’s presence had cast them.”

While Mrs. Noonan had successfully eluded detection for some ten years, at least one officer was aware of her disguise. First

Lieutenant Edward Settle Godfrey noted in 1868 that she was “tall and angular and had a coarse voice” and that “a stiff breeze

whisked the veil off her face and revealed a bearded chin.” Goclfrey’s suspicions were confirmed by Hamilton, who told him

“the story of her employment.” Until the news became public a decade later. Godfrey never spoke of the matter, believing discretion

the better part of honor. The principles of decorum that ultimately destroyed Corporal Noonan had conversely served to protect

his wife’s identity prior to her death.

—JIM WILKE

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

In 1702, Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury, was appointed governor of New York by his cousin, Queen Anne. Cornbury dressed daily

in women’s clothes and commonly made appearances while in full dress and makeup. He posed in a lownecked dress for his official

portrait, holding a fan and wearing a subtle swatch of lace in his hair. He remained governor until 1708. Eventually he returned

to England, where he took a seat in the House of Lords.

Gender roles are ingrained in society and affect nearly all facets of our lives. Depending on the culture, the historical era,

and the geographic region of the world, everything from hairstyles and dress to career choices and marriage have had gender-specific

“norms.” For a variety of reasons, there have always been individuals who have transgressed those norms.

“Passing” is a specific kind of cross-dressing in which a person dons the attire, stance, walk, and attitudes of the opposite

sex in order to pass as that sex. Women throughout history have success-fully passed as men in order to gain access to the

greater economic and political opportunities men have typically possessed. Some men and women have also passed to negotiate

around social stigmas against same-sex love, and many passed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in order to marry

someone of their own gender.

Men who passed as women had many motives aside from access to same-sex intimacy. In a time before gender-reassignment operations

(sex changes), passing as a woman was perhaps the closest one could come to “switching” gender, making passing men and women

early pioneers of the transgender community. In addition, while men have historically had greater opportunities both politically

and economically, the limitations of social expression in a dual-gendered society cuts both ways. From a very young age boys

were, and still are, socialized to deny themselves access to certain kinds of activities (like playing with dolls and holding

hands with other boys) and to define occupations in terms of gender (e.g., nurses are women and doctors are men). By passing

as women, men could engage in activities that society would deem “unacceptable” for men.

In many traditional Native American cultures, cross dressing and transgressing gender norms was celebrated. Berdache, as French

explorers called cross-gender Native Americans, were often seen as mystics and seers. Often, cross-gendered people were simply

incorporated into the roles and activities of the opposite sex. Unlike most other people of the culture, many berdache had

both sexual and emotional same-sex relationships.

“When I was about twenty [in the 1860s] I decided that I was almost at the end of my rope. I had no money and a woman’s wages

were not enough to keep me alive. I looked around and saw men getting more money and more work, and more money for the same

kind of work. I decided to become a man. It was simple. I just put on men’s clothing and applied for a man’s job. I got it

and got good money for those times, so I stuck to it.”

“When I was about twenty [in the 1860s] I decided that I was almost at the end of my rope. I had no money and a woman’s wages

were not enough to keep me alive. I looked around and saw men getting more money and more work, and more money for the same

kind of work. I decided to become a man. It was simple. I just put on men’s clothing and applied for a man’s job. I got it

and got good money for those times, so I stuck to it.”

CHARLES WARNER, WHO PASSED AS A MAN IN SARATOGA SPRINGS, NEW YORK, FOR OVER SIXTY YEARS

By the twentieth century, much cross-dressing in the United States had less to do with passing than it did with identifying

with lesbian and gay cultures. Butch and femme roles have enjoyed a resurgence in recent years, as lesbians have come to appreciate

the distinctive pleasures and freedoms from gender expectations such roles can bring.

Drag, too, has its history. Entertainment drag was an important part of cabaret theater in the early and mid twentieth century,

and continues in various forms today. We’ve compiled a list of some of the great drag performers of that era.

Clothes and attitude, it seems, do make the man (and, of course, the woman)

In 1951, Ebony printed an article about Georgia Black, a man who had passed as a woman for thirty years in a small southern town. It is

a rare glimpse into the life of a passing man who negotiated sexuality and gender to become the woman she truly wanted to

be. Given the historical context of the piece, Ebony, while relying on popular notions of homosexuality, gives Georgia the dignity she deserved in a community that embraced her

even after it was discovered she had been a he. Below is an abridged venison of that article.

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

Murray Hall passed for over twenty-five years as a man. During that time, she voted, married twice, and became a prominent

New York politician in the 1880s and 1890s. She had breast cancer for years, and was near death when she finally confided

in a doctor. The doctor neither cured her nor kept her secret, and she died amid public scandal.

By every law of society, Georgia Black should have died in disgrace and humiliation and been remembered as a sex pervert, a

“fairy,” and a “freak.”

But when Georgia Black died in Sanford, Florida, four months ago, both the white and colored community alike paid its solemn

tribute. A funeral cortege wound its way though the hushed crowded streets of the Negro section. And lining the sidewalks

of the Dixie town that had once barred Jackie Robinson from its stadium, Negro and white mourners rubbed elbows, bowed heads,

and shed genuine tears.

Exposure of Georgia Black as a man who had passed for a woman for thirty years was the tragic anti-climax to his death and

revealed one of the most incredible stories in the history of sex abnormalities.

The exposure came about after County Physician Orville Barks of Sanford, Florida, found to his shocked amazement that the

sick “woman” he was examining had all the physical characteristics of’ a man.

Black’s decision to camouflage these characteristics and cross the sex line was made when, as a fifteen-year-old boy (then

named George Canter) on a farm near Galesville, South Carolina, he rebelled against the grueling slavery of work in the fields

and ran away to Charleston. There he became a house servant in a mansion where a homosexual—a male retainer at the mansion—invited

hint to become his “sweetheart.” Illiterate, untutored, and insecure, having only a faint notion of right and wrong, the simple

farm boy from the South Carolina hinterlands gracefully accepted. Black’s “boyfriend” dressed him in women’s clothes and coached

him in feminine actions and mannerisms.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

According to historian Allan Bérubé. “Jeanne Bonnet grew up in San Francisco as a tomboy and in the 1870s, in her early twenties,

was arrested dozens of times for wearing male attire. She visited local brothels as a male customer, and eventually organized

French prostitutes in San Francisco into an all-woman gang whose members swore off prostitution, had nothing to do with men,

and supported themselves by shoplifting. She traveled with a special friend, Blanche Buneau, whom the newspapers described

as ‘strangely and powerfully attached’ to Jeanne. Her success at separating prostitutes from their pimps led to her murder

in 1876.”

Under the schooling of this unidentified “boyfriend,” the masquerade of Georgia Black became second nature. Even when his

“lover” eventually forsook him, Georgia had become so accustomed to an unnatural way of life that he began looking for another

man. In Winter Garden, Florida, Black met Alonzo Sabbe, at the time a seriously ill man. An unselfish, generous person, Georgia

nursed Sabbe back to health. When he recovered, Sabbe asked Black to marry him.

It was during the marriage to Sabbe that Georgia adopted a “son,” a fact that made her masquerade all the more convincing.

The “son,” a Pennsylvania steelworker, was devoted to his “mother,” often sent her gifts and money, and was astounded to learn

Black’s true sex. Sabbe died shortly after the marriage and Georgia, now living in Sanford, married again.

Her second husband was Muster Black. The marriage took place in the home of Mrs. Joanna Moore, principal of Sanford’s Negro

elementary school. A prominent Negro minister officiated. Black, a World War I vet, died seven years after the marriage. As

his “widow,” Georgia collected a pension from the Veterans Association.

The reverence that friends and neighbors gave gentle Georgia Black in death was equaled only by tile fierce loyalty townsfolk

of both races accorded him during the last days of his life when sensational radio and newspaper publicity revealing his true

sex spilled across the nation.

Dr. Orville Barks, the county physician who reported Black’s secret, seemed somewhat regretful that he had become involved.

A number of’ people bitterly condemned Barks for what they termed his “indiscreet” revelation.

Members of the St. James Methodist Church uttered approving “amens” each Sunday as Pastor Thomas Flowers asked their prayers

for “our worthy Sister Black, who was even one of the most important leaders in our church.” Succinctly, Sanford public opinion

was divided into two classes: those who didn’t believe Black had deceived them, and those who didn’t care.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Current anti-cross-dressing laws in New York State originated as an attempt by the early state legislature to prevent militant

farmers from committing acts of civil disobedience while dressed as Native Americans.

Mr. and Mrs. Walter Hand, who operate Sanford’s Greyhound bus agency, were in the class of nonbelievers. Representative of

the well-to-do whites who stoutly defended Black, the Hands said Georgia had done domestic work in their home for ten years.

“Georgia is a perfectly wonderful person,” Mrs. Hand declared. “I don’t believe what they say about her.”

Another wealthy Sanfordite, for whom Black did domestic work, said defiantly, “I don’t care what Georgia Black was. She nursed

members of our family through birth, sickness, and death. She was one of the best citizens in town.”

Black himself gave the impression of an amazing innocence of the double life he had led. In fact, despite all the evidence,

official statements, and pictures. Georgia insisted that fate had intended hire to be a female. Admitting that he had male

organs, he dismissed them as “growths,” and declared he had never had any emotional feeling for a woman.

“The doctor says he didn’t see how I coulda married, but I don’t pay no ’tention to that doctor. My husbands and me had a

peaceful, lovely life,” he stated.

A month before his death, as he lay in his bed, arms skin and bone, fingernails like thick encrustations of lime, sunken jaws

sloping down to a chin covered with a light, white heard, Georgia told Ebony his story. His clear, dark eyes gave life to the wasted face, topped with coarse, heavy, black hair, fringed with white where

the dye had faded. The final thing he said was:

“I never clone nothin’ wrong in my life.”

People in Sanford, where Black lived and died, loved and was loved, agree.

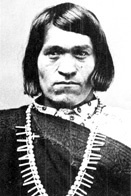

Over 133 North American tribes have been documented to have berdache, or two-spirit, roles in their societies. Berdache were

individuals with alternative gender roles, involving cross-gender behavior or same-sex relationships (for example, men who

did traditional women’s work or women who engaged in hunting and warfare). While some tribes gave no formal name to this behavior,

an equal number formalized the two-spirited roles within their cultures. Listed below are several tribes from around North

America with berdache roles:

We’wha (Zuni) (Courtesy of National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

| Tribe |

Region |

Male Role |

Female Role |

| Blackfeet |

Plains |

ake’skassi |

sakwo’mapi akikwan |

| Cheyenne |

Plains |

heemaneh’ |

|

| Cocopa |

Southwest |

elha |

warhamch |

| Dakota |

Plains |

wingkta wingkte |

koskalaka |

| Klamath |

Colombia Platean |

tw!inna’ek |

tw!inna’ek |

| Kutenai |

Columbia Plateau |

kupalhke’tek |

titqattek |

| Maricopa |

Southwest |

ilyaxai’ |

kwiraxame’ |

| Mojave |

Southwest |

alyha |

hwami |

| Northern Paiute |

Great Basin |

tuva’sa |

moroni noho |

| Shoshoni |

Great Basin |

tubasa |

nuwuduka waippu sungwe |

| Zuni |

Southwest |

lhamana |

katsotse |

From the beginning of the century through the 1930s, drag performers enjoyed a heyday in New York City everywhere from seedy

dives to Broadway, and the popularity of female impersonation spread across the country. By the late 1930s, drag performance

had been driven underground, primarily existing in gay clubs. There were, however, exceptions, such as T. C. Jones, who played

on Broadway in New Faces of 1956. Jones always removed his wig at the close of a performance. Here are seven other famous female impersonators from

history:

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Lavish costume and drag balls were popular in America from the 1820s through the 1930s, and were great social occasions in

New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, New Orlcans, and Chicago. Dozens of enormous gay balls took place in Harlem and Greenwich

Village each year from the 1860s through the 1930s. Society people, politicians, and flamboyant homosexuals rubbed shoulder

pads at these events. The Vanderbilts were known to attend New York’s Hamilton Lodge Ball, as was May Jimmy Walker (sometimes

in drag).

1. Gene Malin was a six-foot, 200-pound effeminate man who performed both in and out of drag costume. Briefly, in the late 1920s, he was

the top earner of Broadway. By 1932, he had moved to a club in Hollywood hearing his name. A year later, Malin’s career was

cut tragically short when the twenty-five-year-old drove his automobile off a pier and drowned.

2. Julian Eltinge was active from the end of the nineteenth century through 1940. Though presumed to be homosexual, Eltinge went to extraordinary

lengths to stress his heterosexuality, beating up stagehands, members of the public, and fellow vaudevillians who made any

suggestive remarks about his sex life.

3. Karyl Norman billed himself as “The Creole Fashion Plate,” but was known behind his back as “The Queer Old Fashion Plate.” Milton Berle

recalls that Norman was so used to wearing high heels that by the late 1920s. he found it impossible to put on stale footwear.

4. Bert Savoy teamed up with another gay man, Jay Brennan, who appeared in male attire. Much of Mae West’s personae was inspired by Savoy.

On June 26, 1923, rumor has it that he and a friend were walking on Long Beach, Long Island, when a thunderstorm swept across

the area. After a particularly strong clap of thunder, Savoy commented, “Mercy, ain’t Miss God cutting up something awful?”

Immediately, there was a lightning bolt from the sky and both Savoy and his friend were instantly killed.

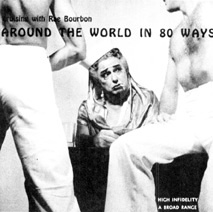

5. Rae Bourbon performed around the country from the 1930s through the 1960s. His raunchy behavior caused him to be ostracized from other

female impersonators and frequently landed him in jail. In the mid-fifties, as a publicity stunt, he claimed to have had a

sex change in Mexico per-formed by a Hungarian doctor. In 1968, he was accused of murder, and three years later, he died in

a Texas jail hospital of a heart attack.

6. Jose Sarria gained fame for his many performances at the Black Cat on Montgomery Street in San Francisco, a popular bar for the city’s

gay and bohemian subcultures of the 1950s. His famous performances included his own parodies of grand operas like Aida and Carmen. Aside from his talents on the stage, he ran unsuccessfully for the Board of Supervisors in 1961, the first openly gay candidate

in the nation. In 1960 he became the first Empress of San Francisco, beginning what continues today as the Imperial Court.

Around the World in 80 Ways was Rae Bourbon’s eighth album. Others included You’re Stepping on My Eyelashes. Hollywood Expose, and Let Me Tell You About My Operation. (Collection of Don Romesburg)

7. Billy Jones was perhaps Atlanta’s (and the South’s) most famous drag queen in the 1960s and 1970s. Beginning in 1961, he performed as

Phyllis Killer at the Joy Lounge and as head of “Billy and the Beautiful Boys” at Club Centaur. He also hosted the Phyllis

Killer Oscar Awards for seventeen years.

—ANTHONY SLIDE

Butch-femme relationships are a style of lesbian loving and self-presentation that can in America be traced back to the beginning

of the twentieth century. Butches and femmes have separate sexual, emotional, and social identities outside of the relationship.

Some hutches believe they were born different from other women; others view their identity as socially constructed.

While no exact date has yet been established for the start of the usage of the terms “butch” and “femme,” oral histories show

their prevalence from the 1930s on. The butch-femme couple was particularly dominant in the United States, in both black and

white lesbian communities, from the 1920s through the 1950s and early 1960s.

Because the complementarity of butch and femme is perceived differently by different women, no simple definition can be offered.

When seen through outsiders’ eyes, the butch appears simplistically “masculine,” and the femme, “feminine,” paralleling heterosexual

categories. But butches and femmes transformed heterosexual attitude and dress into a unique lesbian language of sexuality

and emotional bonding. Butch-femme relation-ships are based on an intense erotic attraction, with its own rituals of courtship,

seduction, and offers of mutual protection. While the erotic connection is the basis for the relationship, and while hutches

often see themselves as the more aggressive partner, hutch-femme relation-ships, when they work well, develop a nurturing

balance between two different kinds of women, each encouraging the other’s sexual-emotional identity. Couples often settle

into domestic long-term relationships or engage in serial monogamy, a practice Liz Kennedy and Madeline Davis (authors of

Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold) trace back to the thirties, and one they view as a major lesbian contribution to an alternative for heterosexual marriage.

In the fifties, butch-femme couples were a symbol of women’s erotic autonomy, a visual statement of sexually and emotionally

full lives that did not include men.

In the fifties, hutch women, dressed in slacks and shirts and flashing pinky rings, announced their sexual expertise in a

public style that often opened their lives to ridicule and assault. Many adopted tens clothes and wore “DA” haircuts. The

butch woman took as her main goal in love-making the pleasure she could give her femme partner. This sense of dedication to

her lover rather than to her own sexual fulfillment is one of the ways a hutch is clearly distinct from the men she is assumed

to be imitating.

Before androgynous fashions became popular, many femmes were the breadwinners in their homes because they could get jobs open

to traditional-looking women, but they confronted the sane’ public scorn when appearing in public with their hutch lovers.

Contrary to gender stereotyping, many femmes were and are aggressive, strong women who take responsibility for actively seeking

the sexual and social partner they desire.

(Andrea Natalie)

Particularly in the fifties and sixties, the hutch-femme community became the public face of lesbianism when its members formed

bar communities across the country. In earlier decades, butch-femme communities were tightly knit, made up of couples who,

in some case, had long-standing relationships. Exhibiting traits of feminism before the seventies, butch-femme working-class

women lived without the financial and social securities of the heterosexual world. Younger butches were often initiated into

the community by older, more experienced women who passed on the rituals of dress, attitude, and erotic behavior.

Bars were the social background fur many working-class hutch-femme communities, and it was in their dimly lit interiors that

hutches and femmes could perfect their styles and find each other. In the fifties, sexual and social tension often erupted

into fights and many hutches felt they had to be tough to protect themselves and their women, riot just in bars, but on the

streets as well.

With the surge of lesbian feminism in the early seventies, butch-femme women were often ridiculed and ostracized because of

their seeming adherence to heterosexual role playing. In the eighties, however, a new understanding of the historical and

sexual-social importance of butch-femme women and communities began to emerge. Controversy still exists about the value of

this lesbian way of loving and living, however. The American lesbian community is now marked by a wide range of relational

styles: Butch-femme is just one of the ways to love, but the hutch-femme community carries with it the heritage of being the

first publicly visible lesbian community.

—JOAN NESTLE, REPRINTED FROM THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HOMOSEXUALITY

During the 1920s and early 1930s, what has come to be known as the Harlem Renaissance reshaped and celebrated African American

culture. Often ignored, however, is the incredible contribution that the Harlem Renaissance has made to lesbian and gay community

and culture.

Hopeful for social progress and new possibilities, many young and progressive African Americans flocked to Harlem, a mecca

for these self-defined “New Negroes.” Harlem became the worldwide center for African American jazz, literature, and the visual

arts, and a place known for a bohemian, decadent nightlife.

It was within the arts and nightclub scenes of Harlem that lesbian and gay life was most openly explored and expressed. For

African American and white homosexuals alike, Harlem provided a particular kind of freedom, and saw an early formation of

a self-aware lesbian and gay community in the United States.

Many lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals, Black and white together, developed a tangible if tentative collective identity in New

York during the 1920s and 1930s. The Harlem Renaissance, long celebrated in African American history for its rejuvenation

of an oppressed people’s culture, art, literature, and especially music, also served as a queer renaissance within a renaissance.

After World War I created a growth in industrial production in the northern United States, great numbers of Blacks migrated

north from southern rural areas to fill factory jobs that were opening up for them. By the 1920s, large African American communities

had formed in cities across the north, most notable in Detroit, Chicago, and Buffalo. Of these communities, however, New York’s

I laden’ was by far the biggest and brightest, a subcity with Black residents in charge of every aspect of their community.

The 1920s and 1930s are also known as the Jazz Age. This music radiated the Harlem social sensibility regarding sex and sexuality.

Some of the legends of the blues—Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters. Gladys Bentley, and Ma Rainey, to name a few—played integral

rulers in shaping Harlem’s musical and sexual subcultures. These singers were not only long on talent and sass, they also

lied openly bisexual and lesbian lives.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

During a “pansy” craze in New York in the 1930s, straight couples would attend drag balls and flock to cabaret acts with female

impersonators. According to George Chauncey in Gay New York, “If whites were intrigued by the ‘primitivism’ of black culture [in Harlem] heterosexuals were equally intrigued by the.‘perversity’

of gay culture.”

The whole of the Black experience in America—poverty, racism, love, hate, homesickness, and loneliness—is reflected in the

blues, where life’s too rough to limit one’s possibilities for happiness. The blues, and the blues community, accepted sexuality

in all its manifestations. The blues reflected a certain toleration for bi- and homosexuality in antiestablishment Harlem.

Many blues artists took full advantage of this situation.

Gladys Bentley was perhaps the brassiest of her fellow blues singin’ queers. Weighing 250 to 300 pounds, this dark, imposing

woman with the masculine voice and white tuxedo lit up the famous Harry Hansbemv-’s Clara House, where she often gigged as

a featured performer. The smoky nightclub on 133rd Street got even smokier when Gladys was at the piano, belting out familiar

tunes peppered with saucy, sometimes downright obscene, new lyrics. Bentley, who was bisexual, profited from her role as a

“male impersonator” and played up the stereotypical “bull-diker image people flocked to Marlene to see. Regular colubgoers

and celebrities alike were her fans. The crowning jewel in her lesbianism came in the form of a civil ceremony performed in

New Jersey, where Bentley married another woman.

Known as the “Mother of the Blues,” Ma Rainey was another Black lesbian singer with an attitude. In her famous song “Prove

It On Me,” Rainey sings:

Went out last night with a crowd of my friends,

They must have been women ’cause I don’t like no men

They say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me,

They sure got to prove it on me…

Prior to recording the song, Rainey proved it on herself in 1925 when she was arrested for throwing a dyke orgy at her flat,

featuring some hot numbers from her all-female chorus. The incident also proved to be financially lucrative in light of the

“scandal” that followed. “Prove It On Me,” advertised with a picture of a squat, dark woman (a striking resemblance to Rainey

herself), decked out in full male drag chatting up two femme flappers, skyrocketed record sales. Ma Rainey defended her lesbian

experiences with a ferocity.

The avenues through which these extraordinary women plied their trade were not limited to Harlem’s public nightspots. The

blues, jazz, and dancing (as well as some fabulous bootleg booze) were regular fixtures at rent parties, private affairs to

raise money for rent when times were tight. Rent parties were the ideal place for lesbians and gay men to mingle in relative

safety, which they did with relish. Bessie Smith sang about one such party in “Gimme a Pigfoot and a Bottle of Beer.” Harlem

rent parties garnered a reputation well outside the city for their Babylonian abandon, as examples of the freer path-ways

to exploring sexual alternatives expressed in the music of the era.

Just as both queer men and women participated actively in rent parties, both male and female queerness was celebrated in the

blues. Though the ladies grabbed a majority of the blues spotlights singing about each other, male singers got into the act

as well, and thrived. Women and men sang about themselves and each other. George Hanna performed many a gender-bending tune,

perhaps the most famous of which is “The Boy in the Boat,” an ode to the joys of woman-to-woman encounters:

lots of these dames had nothin’ to do.

Uncle Sam thought he’d give ‘em a fightin’ chance.

Packed up all the men and sent ’em to France,

Sent ’em over there for the Germans to hunt,

Left all the women at home to try out all their new stunts.

You think l’m lyin’, just ask Tack Ann

Took many a broad from many a man.…

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Bruce Nugent’s “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade!” was the first published story on homosexual love written by an African American;

it was published in the magazine.FIRE! in 1926. The following is an excerpt:

“Alex turned in his doorway…up the stairs and the stranger waited for him to light the room … no need for words … the, had

always known each other …as they undressed by the blue dawn … Alex knew he had never seen a more perfect being … his body

was all symmetry and music. …Alex called him Beauty. … Long they lay … blowing smoke and exchanging thoughts … and Alex swallowed

with difficulty … he felt a glow of tremor …, and they talked and … slept.”

“Freakish Blues” is another song in which George Hanna blurs the lines of sexual boundaries in much more explicit terms.

A cursory glance at some blues lyrics may not fill one with the greatest sense of queer positivity. “Sissy Man Blues,” a song

recorded by a variety of male vocalists. insists: “if you can’t bring me a woman, bring me a sissy man.” Ma Rainey wrote about

her husband’s homosexual exploits with a queer called “Miss Kate.”

A deeper look reveals that though some songs poke fun at and even question some aspects of queerdom, none of them arc written

with any real contempt toward homosexuality. Humored to have been initiated into “the Life” by friend and mentor Ma Rainey,

singer Bessie Smith’s lesbian pursuits were well documented, although she was married to a man. In addition, the women in

her mid-1920s show “Harlem Frolics” were known for getting involved with each other. When it came to learning women-loving

ways, Smith had a front-line education.

The blues pokes fun and questions most things. typically shrugging its shoulders in the end and saying, “Oh well, that’s just

the way it is.” Blues singers are like that kid in grade school who pulled your ponytails but ran from you if you approached…they

teased you if they thought you were groovy. The blues helped lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals not only accept themselves but

turn around and make fun of themselves as well. There are few more distinctively queer characteristics or stronger gay weapons

of modern life than an ironic sense of humor.

—ARWYN MOORE

Langston Hughes was widely regarded by contemporaries as gay. But his chief biographer, Arnold Rampersad, devotes much space

to “proving” that Hughes wasn’t, despite the poet’s having shown no particular love interest in women, and the fact that he

was often seen running around with effeminate and pretty young men. Rampersad’s reasons:

Langston Hughes at his typewriter in an undated photo. (Bettmann Archives)

1. Hughes couldn’t have been gay because he was not effeminate.

2. Hughes couldn’t have been gay because he didn’t hate women.

3. Hughes couldn’t have been gay because, even though most of his close friends were, he apparently didn’t have sex with them,

or admit to them if he was gay, though he admitted having sex once with a sailor.

4. He apparently didn’t do the gay bar scene.

5. He wrote on gay themes only occasionally.

6. When Hughes shipped out in the Merchant Marine to tile coast of Africa, and the white sailors brought two local boys on

board for a ganghang, Hughes protested instead of joining the fun, as, Rampersad asserts, any gay man obviously would have

done.

Convinced?

You make the call.

—JIM KEPNER

Accompanying the widespread popularity of Harlem’s decadent parties, balls, and music came what historian Lillian Faderman

calls the “sexual colonialism” of Harlem—white, largely middleclass heterosexuals, lesbians, and gay men streaming uptown

to participate in what they perceived as Ilarlem’s free-for-all atmosphere. In Harlem, they felt as though they could escape

the restrictive societal norms imposed on them by colleagues and family. Homosexual experiences were the height of taboo,

and they could have a taste of that as well in Harlem. The Cotton Club and the Clam House were heavily frequented by white

thrill-seekers, anxious to titillate their repressed desires with bootleg liquor, marijuana dens, and peep shows.

For bi- and homosexual whites, however, Harlem represented more than just an exotic place where they could play all night

and escape in the morning. Many felt as though they could, to a degree, relate to African Americans, likening their experiences

with bigotry in mainstream society to the oppression of racism. A tenuous bond could be formed between the white queers and

the Blacks of Harlem, as both sides knew the sting of prejudice. In Blair Niles’s book Strange Brother, the author speaks through one of his characters: “In Harlem I found courage and joy and tolerance. I can be myself there.…

They know all about nee and I don’t have to lie.”

Without doubt, the white upper class exploited Harlem to a degree in those glory days. It is a compromise made by any area

that relies somewhat on tourism for income. Wealthy white patrons introduced the Harlem Renaissance culture to the masses,

resulting in varying levels of misrepresentation.

On the other hand, the whites who went to Harlem for sexual freedom were participants in Black queer culture. They danced

in Black clubs, read Black literature, purchased Black art, and, perhaps above all, listened to Black music. With the aid

of the blues, both white and Black lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals were able to develop a queer consciousness together, in

part because the music and the performers they enjoyed provided the means to recognize and validate themselves with a homosexual

identity more concrete than it had ever been before in American history.

—ARWYN MOORE

For well over half of the twentieth century, the constitutionally guaranteed right to associate freely was denied to lesbians

and gay men. Lesbian and gay men who sought out public social interaction risked harassment, arrest, and the potential loss

of family, friends, and careers.

Yet men who loved other men and women who loved other women did meet: More was at stake than simply having a drink at a local

watering hole or finding sexual gratification in a public bath-room. Finding other homosexuals meant ending the isolation,

if only for a short while, and discovering a community that validated one’s sexuality. Because traditional gathering places

were simply not accessible to them, these courageous gay people sought out, created, and discovered innovative new spaces

to congregate for friend-ship, love, and sex.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Over the course of 1892, police arrested eighteen men for engaging in oral sex in Washington, D.C.’s Lafayette Park.

This section explores the many places gay men and lesbians carved out as safe spaces of their own long before gay liberation.

The variety of locales bears testimony to the innovation of gay men and lesbians in their time.

Cruising at the YMCA has been celebrated in painting—as in a 1933 canvas YMCA Locker Room by Paul Cadmus—in literature—as in the 1920s gay novel The Scarlet Pansy—and in song—as in the popular 1970s Village People song “YMCA.” The ambiguity and the campiness of the Village People’s song

speak to the gay male experience in America, but the song’s lyrics also uncannily reflect the YMCA’s 150-yearold mission to

help urban young men help themselves. Talk of anonymous, public sex at the YMCA often provokes laughter partly because most

people find the thought of men having sex with each other incongruous with the “C” in the Young Men’s Christian Association.

But the Christian mission of the YMCA and the presence of cruising there have evolved together for at least the last hundred

years, maybe longer.

YMCA gyms, locker rooms, and dormitories offered public spaces where men had easy physical access to each other. The Christian

reputation of the YMCA protected cruisers from the police harassment and gay-bashing that were a threat in other public urban

spaces. The YMCA’s pioneering work in American physical culture starting in the 1880s made the YMCA a place where male physical

beauty could be openly contemplated. The Christian mission of the YMCA was not only a great cover for men in the closet, but

it may also have been easier for men burdened with internalized homophobia to frequent a potential cruising area if that place

was Christian. Finally, the images of the kinds of men at the YMCA—“clean-cut” youth, working-class men, and fresh farm boys—attracted

men who were interested in connecting sexually with “real” (i.e., straight) men. The YMCA was often a first stop for young

men moving from the country to the city, and the YMCA introduced man rural young men to the urban gay subculture.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Since gay and lesbian people have often found each other by frequenting the local watering hole, homophobes in some communities

have invented strange laws to keep us invisible. For example, in Virginia for many years it was illegal to serve alcohol to

a homosexual, making gay bars difficult to operate. This predicament led to the establishment of speakeasies where lesbians

or gay men would bring their own alcohol to a designated place and have dances or other social events.

Wayne Flottman grew up in southeastern Kansas and went to the YMCA for the first time in 1958 in Denver, Colorado. “I was

somewhat naive about what went on there,” he recalled, though his first night there he saw “some guy sitting in an open window

totally nude,” which led to his first YMCA sexual encounter. Martin Block recalled a “police friend” in the 1940s who went

to the YMCA for sex because his fellow police officers never raided it. He knew a gay couple in the 1930s who had cruised

at the YMCA in the 1890s. YMCA ministers and leaders also participated in the cruising scene. One ordained minister said he

first heard about the sex scene at the YMCA from other seminarians in the 1950s. Donald Vining’s diary confirmed what many

gay men had long suspected: that YMCA desk staffs were often completely infiltrated by gay men. But being gay was not pre-requisite

for cruising at the Y. “Most of the men I had sex with [at the Y],” recalled one interviewee. “considered themselves completely

straight.”

Cruising at the YMCA has changed since the 1970s, transformed in part by the rise of the gay movement, in part by AIDS. But

without a doubt, it played a key role in the emergence of gay communities and identities in American cities, and in the memories

of the many gay men for whom it lived up to its reputation as—in the words of gay author Sam Steward—“the biggest Christian

whorehouse in the world.”

—JOHN D. WRATHALL

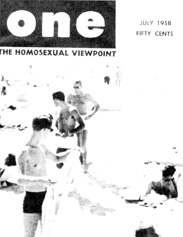

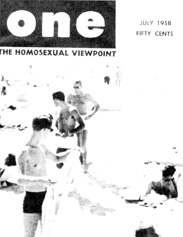

Ihadn’t gone near a gay beach for years when Marty and I drove out last summer to one of California’s most famous. It was a

long pleasant drive out the Boulevard and it seemed that quite a few others were going our way—a red convertible with two

sunbaked blondes; two sporty lesbians in an MG; a carload of screaming queens.…

We arrived early. “Look at that!” Marty said with a sweep of his bronzed arm. “Doesn’t the sight of that crowd thrill you?

Right out in the open, hundreds of our people, peacefully enjoying themselves in public.

“I often lie awake nights wondering how long it’ll take our group to become aware of itself—its strength and its rights. But

I hardly ever appreciate just how many of us there really are except when I come here. Except for a few minutes on the Boulevard

after the bars close, this is the only place where we ever form ‘a crowd,’ and there’s something exciting about seeing homosexuals

as a crowd. I can’t explain how it stirs me, but I think beaches like this are a part of our liberation.”

It was the largest crowd of homosexuals I’d ever seen. I stood around, looking at the remarkably handsome bodies, the colorful

beach togs, the posturings, the camping.

The United States has hundreds of miles of line public beaches, I guess homosexuals like to go swimming as much as anyone

else, and there is something about the beach that makes one want to discard the mask and give up the defensive pretense that

is second nature with most homosexuals. There must be six or eight million homosexuals in this country, so it’s not surprising

that here and there—one narrow sliver of Miami Beach, another in Santa Monica, Laguna Beach, Provincetown, the “Indiana dunes,”

and a few spots like Fire Island—a few cramped areas have come to be known as “gay beach,” “faggot’s beach,” “queer alley.”

“bitch beach,” etc. But in all the learned claptrap I’ve read by so-called authorities on homosexuality, I don’t recall any

realistic description of a gay beach. The “authorities” prefer the clammy atmosphere of the bathhouse or the clandestine bar.

The July 1958 cover of ONE magazine provided a rare glimpse at gay recreational life in the fifties. (San Francisco Gay and

Lesbian Historical Society)

Ronnie Chaise, an angel-faced, willowy young hank clerk I met at the beach that summer, exploded one Sunday when a husky married

couple and two noisy kids settled down near us, looked around a bit, then muttering about “damned queers taking over the place,”

picked up baggage and brats and headed for a more moral beach. Ronnie had just come, slim and dripping, out of the water and

was settling down on his towel when he heard them. “Well, go somewhere else if you don’t want to be contaminated,” he howled.

“You’ve got fifty miles of beach around here and this is all we’ve got. So disappear!”

Later. I suggested that he’d offended them—hardly good public relations.

“I offended them? Then offended us. Why always put the blame on this side? They started it. We weren’t doing anything to spoil their day, except existing. Let

them go somewhere else. This is our beach. It’s small and crowded, but its ours “

“What claim do we have to it?” I goaded him. “The cops and the papers don’t think its ours. And those people had just as much

right here as we have.”

“Rights, hell. You have the rights you earn. So we don’t have a spelled-out legal title to this hundred yards of sand, but

neither do heterosexuals have a title to the rest, or any right to chase us off here, like the police try to do every once

in a while. They’ve taken squatter’s rights on the rest and we’ve taken squatter’s rights on this. And if they don’t want

us ‘contaminating’ the rest of their beaches, then they’d better leave us alone here.

“If I don’t know a patron, I give him a warm glass routine. … When I serve the stranger, I reach behind me and get him a warm

glass. The whole bar buzzes. Those who saw the action tell those who didn’t. … The act of giving the warm glass says, ’I don’t

know this person. No one is to talk to him until I have a chance to find who sent him.’If someone is so interested that he

defies me and talks to him, he, the regular, has bought his last beer in my place.”

“If I don’t know a patron, I give him a warm glass routine. … When I serve the stranger, I reach behind me and get him a warm

glass. The whole bar buzzes. Those who saw the action tell those who didn’t. … The act of giving the warm glass says, ’I don’t

know this person. No one is to talk to him until I have a chance to find who sent him.’If someone is so interested that he

defies me and talks to him, he, the regular, has bought his last beer in my place.”

HELEN P. BRANSON IN GAY BAR

“Nobody told those people they couldn’t spend the day here. They objected to us and left. But there are plenty of other heteros

around here who mind their own business, or maybe even enjoy our company.

“We’ve got to establish our right to have our own little corner, and when guys like that accidentally stumble into it, we

have to see they act decent or get out fast, or we won’t even have this. Now come on, let’s go out and plunk in the water.

I want to get cooled off. I didn’t come out here to talk politics.”

A really nelly one was camping it up in a large crowd of bikini-clad youths nearby. I knew one of them, Billy Forsing, and

Ronnie wanted an introduction, so we went over and joined them. I didn’t hit it off too well. Like an importunate reporter,

more concerned with analyzing the beach than enjoying it, I asked the nelly one if he thought it gave a very good impression

to make such a display in public.

“Well, get this one!” one of the others shrilled, and most of the bunch quickly flounced off for a swim, leaving Ronnie and

me with Billy and George, the nelly one. He turned on me like an angry cat. “You’re darned right I camp it up out here. Why

not? It’s about time these yokels learned to face the fact that we exist. I’m tired of hiding it. I work in a prissy office

where half the guys in the place are really belles, but they’d all faint dead away if anyone dropped a hobby pin. I come out

here to let my hair down, and I let it down good. Anybody else out here is here for the same reason, or else they’ve come

to see the show. Show they want—show they’ll get—from me, at least.” With that, he upped and did a quick imitation of a strip

teaser saucily showing her backside to the audience, and ran off to join his friends.

Then Ronnie and I took off for one of the gay bars facing the beach—and those bars are different from any other gay bars I’ve

ever seen; they’re really a sort of extension of the beach—and then wandered down for a look at bicep-pumpers that were exhibiting

their rippling muscles farther down the beach. And that place in itself is something to write about …some other time.

—FRANK GOLOVITZ EXCERPTED FROM ONE MAGAZINE, JULY 1958

There was nothing very unusual about the Yukon—nothing to make it stand out from dozens of other small gay bars. As in any

neighborhood place, most of the customers during the week were regulars who lived nearby. The bar usually wasn’t jammed until

Friday and Saturday nights and for the Sunday after-noon “beer bust.” Even then, it took only about thirty-five people to

make a mob in the Yukon. So, as I say, there was nothing unusual about the place—that is, not until that Friday night near

the end of March 1996.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

The oldest, continuous gay bar in the United States is The Double Header in Seattle, founded in 1934. It is still run by the

same (straight) family.

On that fateful Friday, I had picked up my lover, Larry, when he got off work. We went to the Yukon and drank beer for an

hour or so. Several friends we hadn’t seen for a while wandered in, and it looked like it was going to be a good fun night.

We went to dinner and got back to the bar by about 10:30. By then the place was crowded, and there was a lot of laughing and

joking around. There were several people I hadn’t seen before, but that, too, was normal on a crowded night.

“Jane Jones” a Los Angeles women’s bar, circa 1942. (Courtesy Paris Poirier)

At one point, about 12:30 A.M., Tommy [the bartender] was passing by and stopped to talk to me. After we talked a few minutes, he looked over my shoulder

toward the door. I turned and saw several uniformed policemen coming in. One of them, whom we later referred to as Hooknose,

yanked the jukebox cord and ordered the lights turned up. The other, who chewed gum steadily, just stood around.

During the 1950s, the Jewel Box Lounge in Kansas City, Missouri, billed itself as “The Most Talked About Night Club in the

Midwest.” Drag performers, called “femme-mimics,” performed musical and comedy numbers in classic cabaret style. (Courtesy

of the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, Chicago, IL)

Hooknose announced, “We’re going to make a few arrests. Just stay where you are. Anyone who runs will be shot.” No one ran.

He went behind the bar, checked the license, then went about his fun task of picking victims.

I’m not sure where he started, but I think it was with two boys dressed in cowboy garb. He then picked George, who was standing

at the bar to Larry’s right. Each tap on the shoulder was punctuated with “You’re under arrest.” At one point he stopped to

count on his fingers, seemingly figuring out how many people the cars outside could take. Then he went back to his grim business.

He skipped over Larry. I felt the dreaded tap and turned. “You’re under arrest.”

Altogether they took twelve people that night—about a third of the patrons. At the Hollywood station, we assembled in a small

room just inside the back door.

Gum Chewer, still chewing, advised us of our “rights.” Then, as we passed through a door into the cell area, he pointed to

each and said, “Lewd conduct.” Then Gum Chewer called us out one at a time and talked to us for a minute or so. When my turn

came, Gum Chewer pointed toward the cell. “See that boy in the blue shirt?” It was Lee; I’ve known him for years but never

had sex with him. “You humped him,” the Man said. I told him I didn’t know what he was talking about.

That’s pretty much the way it went for each one. Lee was accused of groping someone sitting next to him, and that guy was

charged with rubbing legs with Lee. Tommy was supposed to have groped one of the “cowboys.”

When I was booked, I answered the questions about name and address but balked at where I worked. “That’s not necessary, is

it?” I asked, not knowing what they were entitled to know. “You don’t have to say a damn thing.” he snapped back.

After that there was a lot of waiting in little rooms as the cops took mug shots and fingerprints of each person. I couldn’t

understand how some of the guys could joke around and laugh. I was worried about my job and personal matters that this arrest

could make worse. One young Canadian boy was in a state of near-panic. He was so frightened that the cop trying to take his

fingerprints was having a rough time. The cop threatened to knock him off his ass if he didn’t relax, which just made things

worse. The hassle went on for what seemed like a long time.

It was past 4 A.M. when I finally left the jail. I was irritated, tired, scared, and depressed. And I still am whenever I think about that night.

—DAVID S., AS TOLD TO DICK MICHAELS, EXCERPTED FROM THE ADVOCATE, JULY 1968

When Rikki Streicher died in 1994 after a long struggle with cancer, San Francisco’s mayor saw that the city flags flew at

half-mast. As the founder and owner of Maud’s Study, the longest running women’s bar in San Francisco, member of the board

of directors of the Federation of Gay Games, and a local activist, Streicher had a profound effect on the lesbian and gay

communities not only in San Francisco, but nationally as well.

Rikki Streicher (Rink Foto, Courtesy Mary Sager)

While her support of the Gay Games and lesbian and gay athletics was legendary, she is best known as the proprietor of Maud’s

and, later, of Amelia’s, a popular women’s dance club.

Maud’s, which opened in 1966 and quickly became a popular lesbian hangout in the Haight-Ashbury district, was in some ways

typical of pre—gay liberation bars. More than just a bar, it was a safe place for lesbians to congregate, discuss their lives

and issues of the day, play pool, and, of course, drink.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Men have been gathering in bathhouses for sexual gratification and companionship for over a century. But exclusively gay bathhouses

as we know them today did not exist until the 1950s. From the 1970s to the early 1980s, bathhouses enjoyed a boom, and by

1984 there were approximately 200 bathhouses in the United States.

Gay and women’s bars in the forties, fifties, and sixties were a central part of the lesbian community. For many lesbians,

the bars were the only gathering place they had. The local women’s bar was a home away from home, a group living room, and

a community center. Patrons would have birthday, anniversary, and graduation parties at their favorite bar.

Unfortunately, there were very few exclusively lesbian bars, and most lesbians would gather at gay bars that were primarily

patronized by gay men. Drag queens, sissies, and butch and femme women would all gather in the same places out of economic

necessity, a sense of camaraderie, and a need for mutual protection.

In these bars, one might meet friends or sexual partners. Perhaps more significantly, the bars were a place where lesbians

could celebrate their collective sexuality with each other and gay men. More than just being a place where men could love

men and women could love women, the bars were an entire cultural underground that did not exist elsewhere. The lesbian and