One woman gave powerful testimony in the 1986 New York City hearings regarding passage of a citywide civil rights law, saying,

“I am a university professor, a mother of two children, a first-generation Italian American, and a Catholic. By this time,

you have begun to form a composite picture of the person that I am—I’m becoming the sum of various parts. When I add that

I am also a lesbian, everything else I’ve told you now disappears and is forgotten. I have become a ‘lesbian’—a single, solitary

title. Nothing else is important in your perception of me as a person.”

“There will always be someone begging you to isolate one piece of yourself, one segment of your identity above the others,

and say, ‘Here, this Is who I am.’ Resist that trivialization. I am not JUST a lesbian. I am not JUST a poet. I am not JUST

a mother. Honor the complexity of your vision and yourselves.”

“There will always be someone begging you to isolate one piece of yourself, one segment of your identity above the others,

and say, ‘Here, this Is who I am.’ Resist that trivialization. I am not JUST a lesbian. I am not JUST a poet. I am not JUST

a mother. Honor the complexity of your vision and yourselves.”

AUDRE LORDE, AUTHOR, POET, AND ACTIVIST, COMMENCEMENT SPEECH AT OBERLIN COLLEGE, MAY 29, 1989

Faggot, dyke, queer, lesbian, gay, bulldagger, pansy, fairy: These labels don’t begin to describe who we are. It is easily

forgot-ten by nongay people that being gay or lesbian is only one part of who we are. For many of us, our sexual identity

may not even be the most important part of ourselves. Identity is an evolving concept. Our identities are shaped in large

part by the families and communities in which we are raised, the friends we seek out, and the communities we join when we

become adults.

It is misleading to assume that there is one monolithic gay and lesbian community or that there is one kind of gay person.

We all come to our gay and lesbian identities from different paths. We meet at our sexuality, but the paths leading up to

and away from that sexuality are not necessarily shared. In response to being neither quite here nor there, we construct our

own identities based on the qualities we wish to emulate from our multiple communities.

As a group, gay and lesbian Americans are as diverse as any population on earth. We are Latino, African American, disabled,

people with AIDS, Jews, deaf, Native American, white, Asian American, young, middle-aged and old, and more. It is the merging

of the rest of ourselves with our sexuality that creates our individual gay and lesbian identities.

In this chapter we present the voices of many different lesbians and gay men reflecting on their intersecting identities.

Rather than trying to present a total picture of each group, the pieces here are presented in roughly alphabetical order by

author, without regard to any category. Truth telling is not always simple, nor is it easy, yet it is essential if we are

to become proud of who we are. The gay and lesbian people here talk about coming out and finding their own unique identities.

The first place that I went to when I was coming out was the great Latino watering hole Circus Disco. Tried to get into Studio

One but the doorman asked me for two I.D.’s. I gave him my driver’s license and my JC Penny card but it wasn’t good enough.

Hey, what did I know? I was still wearing corduroys.

Circus Disco was the new world. Friday night, eleven-thirty. Yeah, I was Born to Be Alive. Two thousand people exactly like me. Well, maybe a little darker, but that was the only thing that separated me from the

cha-cha boys in East Hollywood.

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

First night at Circus Disco and I order a Long Island Iced Tea,‘cause my brother told me it was the exotic drink, and it fucks

you up real fast. The bartender looks at me with one of those gay-people-recognize-each-other looks. I try to act knowing

and do it back. Earlier that year, I went to a straight bar on Melrose. When I asked for a screwdriver, the bartender asked

me if I wanted a Phillips or a regular. I was never a good drunk.

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

The first guy I met at Circus Disco grabbed my ass in the bathroom, and I thought that was charming. In the middle of the

dance floor, amidst all the hoo-hoo, hoo-hoo, to a thriving disco beat, he’s slow dancing and sticking his tongue down my throat. He sticks a bottle of poppers up my

nose and I get home at five-thirty the next morning.

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

Sitting outside Circus Disco with a 300-pound drag queen who’s got me cornered in the patio listening to her life story, I

think to myself, One day I will become something and use this as an act. At the time I was thinking less about performance art and more about Las Vegas.

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

A guy is heating the shit out of his lover in the parking lot of Circus Disco. Everybody is standing around them in a circle,

but no one is stopping them. One of the guys is kicking and punching the other, who is lying on the ground in a fetal position.

And the first guy’s saying, “You want to cheat on me, bitch? You cheating on me, bitch? Get up, you goddamn faggot piece of

shit!” It was the first time I saw us act like our parents. I try to move in, but the drag queen tells me to leave them alone.

“That’s a domestic thing, baby. Besides, that girl has AIDS. Don’t get near that queen.”

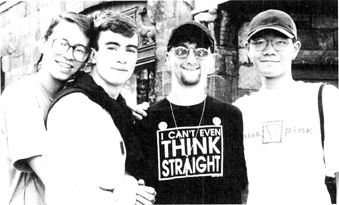

BETTER BLATANT THAN LATENT

(Courtesy ACT UP)

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

I get home early and I’m shaken to tears. My mother asks me where I went. I tell her I went to see a movie at the Vista—an

Italian film about a man who steals a bicycle. It was all I could think of. She says, “That made you cry?”

I swear, I’ll never go back to Circus Disco.…

But at Woody’s Hyperion! Hoo-hoo, hoo-hoo. I meet a guy there and his name is Rick Rascon and he’s not like anyone else. No tight muscle shirt. No white Levi’s. No

colored stretch belt. He goes to UCLA and listens to Joni Mitchell. Is that too perfect or what? He comes home with me and

we make love, but I’m thinking of him more like my brother. And I know we’re gonna be friends for the rest of our lives.

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

Started working at an AIDS service center in South Central. But I gotta get out of here. ‘Cause all of my boys. All of my

dark-skinned boys. All of my cha-cha boys are dying on me. Sometimes I wish it was like the Circus Disco of my coming out.

Two thousand square feet of my men. Boys like me. Who speak the languages of the border and of the other. The last time I drove down Santa Monica Boulevard and I passed by Circus Disco, hardly anybody was there.

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?

— LUIS ALFARO

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

According to a 1989 Department of Health and Human Services study, 28 percent of all high school dropouts are young gay men

and lesbians.

My father asked if I am gay

I asked Does it matter?

He said No not really

I said Yes.

He said get out of my life

I guess it mattered.

My boss asked if I am gay

I asked Does it matter?

He said No not really

I told him Yes.

He said You’re fired, faggot

I guess it mattered.

My friend asked if I am gay

I said Does it matter?

He said Not really

I told him Yes.

He said don’t call me your friend

I guess it mattered.

My lover asked Do you love me?

I asked Does it matter?

He said Yes.

I told him I love you

He said Let me hold you in my arms

For the first time in my life something matters.

My God asked me Do you love yourself?

I said Does it matter?

He said Yes.

I said How can I love myself? I am Gay

He said That is what I made you

Nothing again will ever matter.

— AN ANONYMOUS HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT, FROM GROWING UP GAY/GROWING UP LESBIAN: A LITERARY ANTHOLOGY

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Founded in Los Angeles in 1980, Lesbianas Unidas is the oldest latina lesbian organization in the United States. Among their

many ongoing projects, they sponsor a support group designed specifically for Latina lesbians dealing with the effects of

substance abuse, one of only a handful of such programs in the country.

For the lesbian of color, the ultimate rebellion she can make against her native culture is through her sexual behavior. She

goes against two moral prohibitions: sexuality and homosexuality. Being lesbian and raised Catholic, indoctrinated as straight,

I made the choice to be queer (for some it is genetically inherent). It’s an interesting path, one that continually slips in and out of the white, the

Catholic, the Mexican, the indigenous, the instincts. In and out of my head. It makes for loquería, the crazies. It is a path of knowledge— one of knowing (and of learning) the history of the oppression of our raza. It is a way of balancing, of mitigating duality.

In a New England college where I taught, the presence of a few lesbians threw the more conservative heterosexual students

and faculty into a panic. The two lesbian students and we two lesbian instructors met with them to discuss their fears. One

of the students said, “I thought homophobia meant fear of going home after a residency.”

And I thought, how apt. Fear of going home. And of not being taken in. We’re afraid of being abandoned by the mother, the

culture, la Raza, for being unacceptable, faulty, damaged. Most of us unconsciously believe that if we reveal this unacceptable aspect of

the self our mother/culture/race will totally reject us. To avoid rejection, some of us conform to the values of the culture,

push the unacceptable parts into the shadows. Which leaves only one fear—that we will be found out and that the Shadow-Beast

will break out of its cage. Some of us take another route. We try to make ourselves conscious of the Shadow-Beast, stare at

the sexual lust and lust for power and destruction we see on its face, discern among its features the undershadow that the

reigning order of heterosexual males project on our Beast. Yet still others of us take another step: We try to waken the Shadow-Beast

inside us. Not many jump at the chance to confront the Shadow-Beast in the mirror without flinching at her lidless serpent

eyes, her cold clammy moist hand dragging us underground, fangs bared and hissing. How does one put feathers on this particular

serpent? But a few of us have been lucky—on the face of the Shadow-Beast we have seen not lust but tenderness; on its face

we have uncovered the lie.

— GLORIA ANZALDUA, FROM BORDERLANDS/LA FRONTERA

“Being the supreme crossers of cultures, homosexuals have strong bonds with the queer white, Black, Asian, Native American,

Latino, and with the queer in Italy, Australia, and the rest of the planet. We come from all colors, all classes, all races,

all time periods. Our role Is to link people with each other—the Blacks with Jews with Indians with Asians with whites with

extraterrestrials. It is to transfer ideas information from one culture to another. Colored homosexuals have more knowledge

of other cultures; have always been at the forefront (although sometimes in the closet) of all liberation struggles in this

country; have suffered more injustices and have survived them despite all odds. Chicanos need to acknowledge the political

and artistic contributions of their queer. People, listen to what your jotería is saying.

“Being the supreme crossers of cultures, homosexuals have strong bonds with the queer white, Black, Asian, Native American,

Latino, and with the queer in Italy, Australia, and the rest of the planet. We come from all colors, all classes, all races,

all time periods. Our role Is to link people with each other—the Blacks with Jews with Indians with Asians with whites with

extraterrestrials. It is to transfer ideas information from one culture to another. Colored homosexuals have more knowledge

of other cultures; have always been at the forefront (although sometimes in the closet) of all liberation struggles in this

country; have suffered more injustices and have survived them despite all odds. Chicanos need to acknowledge the political

and artistic contributions of their queer. People, listen to what your jotería is saying.

“The mestizo and the queer exist at this time and point on the evolutionary continuum for a purpose. We are a blending that

proves that all blood is intricately woven together, and that we are spawned out of similar souls.”

WRITER AND ACTIVIST GLORIA ANZALDUA FROM BORDERLANDS/ LA FRONTERA

Poet and filmmaker James Broughton in 1988. (Robert Giard)

As older gay people, what are our major concerns? I don’t think they include making a million dollars, earning world-class

fame, building the next skyscraper, or writing a book that outsells the Bible. In no particular order I believe they include

health, financial security, friendships, networking, and meaning.

“I would assure every man that it is never too late to be surprised by joy. The true love of my life came to me when I was

sixty-one, an age when I was beginning to think it time to pull down the shades and fold up my fancies. Then unexpectedly,

I was blessed with a psychic rebirth.”

“I would assure every man that it is never too late to be surprised by joy. The true love of my life came to me when I was

sixty-one, an age when I was beginning to think it time to pull down the shades and fold up my fancies. Then unexpectedly,

I was blessed with a psychic rebirth.”

JAMES BROUGHTON, POET AND FILMMAKER

Health comes first. Speaking for myself, I take very good care of my body. I see others doing the same thing, especially those

accustomed to working out at a gym. I walk regularly at a quick, steady pace, up and down sharp inclines that make my heart

beat faster. I swim passionately, with real verve and fervor. I love getting in the water, more so if it’s the ocean. I am

under the care of an excellent doctor and an excellent dentist, both of whom I visit faithfully.

In money matters many of us were Depression kids. I remember when my family lost everything in 1929 and the early 1930s. I

became accustomed to frugality and occasional hunger. Those of us who shared this experience of limitation and loss naturally

tend to be prudent and wise about money. We know it does not grow on trees. Also, we remember when a postage stamp cost three

cents, there were hamburgers for a dime, and a kid got into a movie for a quarter. Believe me, this provides a conservative

perspective on today’s spiraling costs and easy-come, easy-go money.

Friendships are, I think, the most precious gifts in the world. Lesbians and gays know their value in a world that was often

unfriendly. Many years ago an older gay couple, two men living in a longtime relationship, offered me friendship when I was

beginning to come to terms with being gay. I desperately needed their understanding, support, experience, and presence in

my life. They provided it unstintingly. I am forever grateful to them. Now I have the opportunity to return their gift by

offering my friendship to younger lesbians and gay men who need the same things they gave me. A corollary of friendship is

networking. It’s about the outreach and involvement of our lives. For example, there is community participation. Volunteerism.

Dialogue with other people about matters of common concern. Being a part of decision making. Networking is the exact opposite

of isolation and loneliness.

Gay American Indians (GAI), founded in 1975 by Barbara Cameron (Lakota Sioux) and Randy Burns (Northern Paiute), has grown

from a San Francisco social club into a national organization of a thousand Indian and non-Indian members. (Rink Foto)

Meaning? It’s as necessary to me as oxygen. Food, drink, sex, and money are not enough for me. I’ve got to come face-to-face

with a new challenge. I need a fresh human need to meet. I yearn for an unexpected mountain to climb. I absolutely require

a compelling reason to greet a new day with cheer and energy.

I find that many older lesbians and gay men I know feel the same way I do. Riding yesterday in the bright red convertible

in the exciting Gay and Lesbian Pride Celebration parade, waving enthusiastically to thousands of people who lined the route,

I felt happy about being gay and older. I am grateful for my life up to this moment: Being gay is a hart of who I am in God’s creation, and so a blessing.

Being older is a new challenge, and a blessing.

— MALCOLM BOYD, EXCERPTED FROM LAMBDA GRAY

When the U S. Supreme Court cited “millennia of moral teaching” in support of Georgia’s sodomy law and when the Vatican declared

homosexuality “intrinsically evil” they must not have been thinking of American history and American morals. Because, throughout

America, for centuries before and after the arrival of Europeans, gat and lesbian American Indians there recognized and valued

members of tribal communities. As Maurice Kenny declares, “We were special!.”

“In some Indian cultures, adolescents were given a choice between the basket or the bow—or other ‘gender-specific” items.

The person was then accepted and raised in the tradition of his or her choice without stigma.”

“In some Indian cultures, adolescents were given a choice between the basket or the bow—or other ‘gender-specific” items.

The person was then accepted and raised in the tradition of his or her choice without stigma.”

CAYENNE WOODS (KIOWA)

Our tribes occupied every region of this continent, and our cultures were diverse and rich—front the hunters of the far North,

to the trading people of the Northwest Coast, the farmers, and city-builders of the Southwest, the hunters of the plains,

and the great confederations of the Northeast.

Gay American Indians were a part of all these communities. We lived openly in our tribe. Our families and communities recognized

us and encouraged us to develop our skills. In turn, we made special contributions to our communities.

French explorers used the word berdache to describe stale Indians who specialized in the work of Women and formed emotional and sexual relationships with other men.

Many tribes had female berdaches, too—women who took on men’s work and married other women. The History Project of Gay American

Indians (GAI) has documented these alternative role, in over 135 North American tribes.

As artists, providers, and healers, our traditional gay ancestors had important responsibilities.

Women hunters and warriors brought food for their families and defended their communities, like the famous Kutenai woman warrior

who became an intertribal courier and a prophet in the early 1800s, or Woman Chief of the Crow Indians, who achieved the third

highest rank in her tribe. Among the Mohave, lesbian women became powerful shamans and medicine people.

Male berdaches specialized in the arts and crafts of their tribes and performed important social and religious roles. In California,

we were often called upon to bury and mourn the dead, because such close contact with the spirit world was considered too

dangerous for others. Among the Navajo, berdaches were healers and artists, while among the Plains Indians, we were famous

for the valuable crafts we made.

“It’s taken more generations for us to get to where we’re at now, but we’ve found a new tool now and that tool is speaking

out.”

“It’s taken more generations for us to get to where we’re at now, but we’ve found a new tool now and that tool is speaking

out.”

ERNA PANE (NAVAJO)

Gay and lesbian American Indians today represent the continuity of this tradition. We are living in the spirit of our gay

Indian ancestors. Much has changed in American Indian life, but we are still here, a part of our communities, struggling to

face the realities of contemporary life.

Some of us continue to fill traditional roles in our tribal communities; others are artists, healers, mediators, and community

organizers in urban areas; many of us are active in efforts to restore and preserve our cultural traditions.

Gay and lesbian Indians were special to a lot of tribes. We have roots here in North America.

— RANDY BURNS (NORTHERN PAIUTE, CO-FOUNDER, GAI, EXCERPTED FROM THE PREFACE OF LIVING THE TRADITION, ED. WILL ROSCOE

From the first description of cases in the New York Native in the spring of 1981, there was never a question in my mind that I would get GRID. I retain a clear image of myself on a

subway platform at rush hour, frozen in place, reading for the first time about a new, lethal, sexually transmitted disease

that was affecting gay men. I remember feeling disoriented by the knowledge that life was going on all around me, oblivious

to the fact that my world had just changed utterly and forever.

By late 1981, my doctor and I both knew that I had GRID. I was experiencing mysterious fevers, night sweats, fatigue, rashes,

and relentless, debilitating diarrhea. I was losing weight and feeling more and more miserable.

In June 1982, I collapsed from dehydration and was admitted to the hospital with a high fever and violent, bloody diarrhea.

When a doctor walked into my room and announced, with the satisfaction of Miss Marple, that I was now official, I was strangely

relieved.

“Well, it’s GRID all right,” she said. “You have cryptosporidiosis. Before GRID, we didn’t think cryptosporidiosis infected

humans. It’s a disease previously found only in livestock.”

I tried to take in the fact that I had a disease of cattle!

Michael Callen, singer, songwriter, and AIDS activist. Callen died of AIDS-related causes in 1994. (Joel Sokolov)

“I’m afraid there is no known treatment…”

I thought I was prepared for this moment, but I felt myself beginning to go numb.

“All we can do is try to keep you hydrated and see what happens. Your body will either handle it or … it won’t.”

She smiled, not too optimistically, patted my leg, and left me alone to confront in earnest the very real possibility of my

imminent death.

— MICHAEL CALLEN, FROM SURVIVING AIDS

All it takes is “Ahhlo, Quang?” for me to realize it’s family calling. The sound of my name, spoken like it’s supposed to be,

massages from my temples to the back of my neck. I lean back, awash—it’s my name, and yet it’s been months since I’ve heard

it right.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

In 1987, the first U.S. conference for lesbian and gay Asians and Pacific Islanders, called “Breaking the Silence: Beginning

the Dialogue” attracted eighty-five participants to North Holly-wood, California. The key-note speaker, Trinity Ordona, a

Filipina lesbian, said “It is out of self-empowerment that comes collective empowerment.… We must break the silence to our-selves

and shout our gayness so strongly that the social order to things changes to really include us.”

My great aunt Bà Cô is visiting my cousins for a week. My lover and I live nearby. Still. I manage excuses why I can’t visit

tonight. Over the phone, I hear my nephews and nieces screaming around.

Bà Cô commends me for being calmer when I was younger. She tells me the story of how quietly I held her hand throughout our

escape from Vietnam in 1975; she recalls a panic—the time she momentarily lost my grasp in a crowded camp in Guam. She was

able to retrace her steps to find me where we’d been separated: I’d stood in the same place, as instructed. She’s told me

this story only three times in my life, but I recount all the times I’ve thought of it, as a bond between me and her, and

me and my family.

At another time in my life, it might have been easy to set things aside and go see Bà Cô. Things haven’t been so simple since

I came out. To start with, Bà Cô’s older, from another time, another place. It would break her heart to see me, bright red-orange

hair, pierced ears, and all. Easy solution, shave the head and take out the piercings.

Not so easy.

“We are relatively uninformed about Asian American subcultures organized around sexuality. There are Asian American gay and

lesbian social organizations, gay bars that are known for Asian clientele, conferences that have focused on Asian American

lesbian gay experiences, and electronic bulletin boards catering primarily to gay Asians, their friends, and their lovers.”

“We are relatively uninformed about Asian American subcultures organized around sexuality. There are Asian American gay and

lesbian social organizations, gay bars that are known for Asian clientele, conferences that have focused on Asian American

lesbian gay experiences, and electronic bulletin boards catering primarily to gay Asians, their friends, and their lovers.”

DANA TAKAGI, SOCIOLOGY PROFESSOR AT UC SANTA CRUZ

I choose to look the way I do because it makes me feel beautiful. And then there’s the part about getting off on retaking

people deal with me, as a freak. I have similar reasons for living my life out as a gay man. Being queer, living queer, I

can makeitfinditexploreitadoreit. I choose it because living queer means breaking rule #1, so why stop there?

Before I see Bà Cô, I will probably cut my hair. Changing the way I look is not the biggest deal. I some-times wear a hat

in law school classes so the instructor won’t single me out. They can see (when they’re looking) I’m Asian, some may even

guess I’m gay; in a situation where someone has so much power over me, being a freak is less a priority. So I concede, I change

my look to be safe at times, to be anonymous at school. So of course I’ll do it to spare Bà Cô. But these are acts of hiding,

which I must endure and remember.

Coming out has caused much pain, cutting me away from my family. My parents and I dwell on nonsubjects, dancing around my

sexuality on the rare occasions we speak on the phone. Maybe it’d be better had I not told them. I moved 3,000 miles away, a distance I desperately needed to start living on my own terms. Almost two decades before, my

family fled from war, across the world to stake a new life. Survival was the goal, success our reward.

Now separation marks our dream-fulfilled, torn apart again. My parents fought to bring me to this country, for a chance at

happiness, which I have by my terms found. I—am in love/can turn to deep friendships/have [not lost] two wonderful sisters/find power from (in) my communities/take privilege

from higher education. And I can’t share one bit of it with them.

I can lose the piercings and the hair, but the deception goes deeper. If Bà Cô asks about my life, I will focus on school,

be ambiguous, lie. In this life, in my fight, coming out grants escape from bleakness, but the refuge(e) is not complete.

There are new struggles and compromises. Every day, I come out of some closets, only to go back into others.

— QUANG N. DANG

It is of particular importance to us as third world gay people to begin a serious interchange of sharing and educating ourselves

about each other. We not only must struggle with racism and homophobia of straight white america, but must often struggle

with homophobia that exists within our third world communities. Being third world doesn’t always connote a political awareness

or activism. I’ve met a number of third world and Native American lesbians who have said they’re just into “being themselves,”

and that politics has no meaning in their lives. I agree that everyone is entitled to “be themselves,” but in a society that

denies respect and basic rights to people because of their ethnic background, I feel that individuals cannot idly sit by and

allow themselves to be coopted by the dominant society. I don’t know what moves a person to be politically active or attempt

to raise the quality of life in our world. I only know what motivates my political responsibility… the death of Anna Mae Aquash—Native

American freedom fighter—“mysteriously” murdered by a bullet in the head; Raymond Yellow Thunder—forced to dance naked in

front of a white VFW club in Nebraska—murdered; Rita Silk-Nauni—imprisoned for life for defending her child; my dear friend

Mani Lucas-Papago—shot in the back of the head outside of a gay bar in Phoenix. The list could go on and on. My Native American

history, recent and past, moves me to continue as a political activist.

“The tradition of the gay Indian has always been a real special one, like someone who is touched by something special.”

“The tradition of the gay Indian has always been a real special one, like someone who is touched by something special.”

BETH BRANT (MOHAWK)

And in the white gay community there is rampant racism that is never adequately addressed or acknowledged. My friend Chrystos

from Menominee Nation gave a poetry reading in May 1980 at a Bay Area feminist bookstore. Her reading consisted of poems and

journal entries in which she wrote honestly from her heart about the many “isms” and contradictions in most of our lives.

Chrystos’s bluntly revealing observations on her experiences with the white-lesbian-feminist community are similar to mine

and are probably echoed by other lesbians of color.

Her honesty was courageous and should be representative of the kind of forum our community needs to openly discuss mutual

racism. A few days following Chrystos’s reading, a friend who was in the same bookstore over-heard a white lesbian denounce

Chrystos’s reading as antilesbian and racist.

“I’m a weaver of social fabric. As I travel and relate the stories of different cultures that people have told me, I help

to create a more direct link between cultures and among individuals. It we all realize how much we have in common, then the

craziness of our world leaders will start to evaporate.…[As a child] I had to speak through t e heterosexual mouth. I learned

how to use pronouns and how not to use pronouns—‘My friend and I went for a walk.’ Things like that were chipping slowly away

at my consciousness and making me become a revolutionary.”

“I’m a weaver of social fabric. As I travel and relate the stories of different cultures that people have told me, I help

to create a more direct link between cultures and among individuals. It we all realize how much we have in common, then the

craziness of our world leaders will start to evaporate.…[As a child] I had to speak through t e heterosexual mouth. I learned

how to use pronouns and how not to use pronouns—‘My friend and I went for a walk.’ Things like that were chipping slowly away

at my consciousness and making me become a revolutionary.”

FLOATING EAGLE FEATHER, GAY NATIVE AMERICAN STORYTELLER

A few years ago, a white lesbian telephoned me requesting an interview, explaining that she was taking Native American courses

at a local university, and that she needed data for her paper on gay Native Americans. I agreed to the interview with the

idea I would be helping a “sister” and would also be able to educate her about Native American struggles. After we completed

the interview, she began a diatribe on how sexist Native Americans are, followed by a questioning session in which I was to

enlighten her mind about why Native Americans are so sexist. I attempted to rationally answer her inanely racist and insulting

questions, although my inner response was to tell her to remove herself from my house. Later it became clear how I had been

manipulated as a sounding board for her ugly and distorted views about Native Americans. Her arrogance and disrespect were

characteristic of the racist white people in South Dakota. If I tried to point it out. I’m sure she would have vehemently

denied her racism.

During the antigay Briggs Initiative scare in 1978, I was invited to speak at a rally to represent Native American solidarity

against the initiative. The person who spoke prior to me expressed a pro-Bakke sentiment that the audience booed and hissed.

His comments left the predominantly white audience angry and in disruption. A white lesbian stood up demanding that a third

world person address the racist comments he had made. The MC, rather than taking responsibility for restoring order at the

rally, realized that I was the next speaker and I was also T-H-I-R-D-W-O-R-L-D!! I refused to address the remarks of the previous

speaker because of the attitudes of the MC and the white lesbian that only third world people are responsible for speaking

out against racism. It is inappropriate for progressive or liberal white people to expect warriors in brown armor to eradicate

racism. There must be co-responsibility from people of color and white people to equally work on this issue. It is not just

MY responsibility to point out and educate about racist activities and beliefs.

Redman, redskin, savage, heathen, injun, american indian, first americans, indigenous people, natives, amerindian, native

american, nigger, negro, black, wetback, greaser, mexican, Spanish, latin, hispanic, chicano, chink, oriental, asian, disadvantaged,

special interest group, minority, third world, fourth world, people of color, illegal aliens—oh yes about them, will the U.S.

government recognize the Founding Fathers (you know, George Washington and all those guys) are this country’s first illegal

aliens?

We are named by others and we are named by ourselves.

— BARBARA CAMERON, EXCERPTED FROM THIS BRIDGE CALLED MY BACK

There were about 200,000 disabled lesbians when I came out of my coma in 1981. AIDS was still “gay cancer.” and lesbians were

still “immune.” Now there are about one million disabled dykes, but back then lesbians evidently thought themselves immune

to all other disabilities too, judging by their discomfort around me. Not to mention the exclusionism and the really thoughtless

things that have been said to me. (One woman actually told me she’d never “let” anything happen to her eyes. since she was

an artist!)

“The ways of the traditional Lakota are to accept things rather than to change them; to learn to work with things and try

to live in peace with them. This does not mean total agreement with the gay lifestyle, but it does mean tolerance. In traditional

values there is a definite place for gays. Even though this does little to shelter the modern gay lifestyle, it does give

an Important validity to homosexuality and, more importantly, a heritage to Indian gays.”

“The ways of the traditional Lakota are to accept things rather than to change them; to learn to work with things and try

to live in peace with them. This does not mean total agreement with the gay lifestyle, but it does mean tolerance. In traditional

values there is a definite place for gays. Even though this does little to shelter the modern gay lifestyle, it does give

an Important validity to homosexuality and, more importantly, a heritage to Indian gays.”

— BEN THE DANCER, IN LIVING THE SPIRIT

I can understand this immune-to-disability feeling, because I used to think the same thing. And I should have known better;

after all, I taught disabled people. I should have realized, more than most people, that disability strikes anybody, anytime,

anywhere.

But there I was, eating healthily, getting plenty of exercise, and never eating salt. I was hardly religious, but I figured

that if you treated others with respect, you’d be left alone.

Wrong.

Even if you do everything “right,” disability can still “get” you.

A lot of my negative experiences since 1981 can be laid at the feet of the [heterosexual] community at large. Like the institutions

that abuse us, the maddening inaccessibility of mostly even’thing, the fact that we have exactly two states that pay for personal

care assistants and that we usually live in ghettos, and the gruesome 60 to 90 percent unemployment rates. The list can go

on, but it’s much too depressing.

The unthinking continuation of physical and attitudinal barriers in gay communities is another way the discrimination occurs.

The AIDS community in Boston took years to recognize the need for wheelchair accessibility. But if it weren’t for gay men’s

acceptance of me, disability and all. I fully doubt I’d be here. I got invited by one of the sponsors of Woman of Color Press

to a reading, but when I got there, no wheelchair seating section was to be found. Yet women of color have taught me how not

to lash out at the practitioners of racism and exclusionism.

It’s hard not to feel isolated and alienated. Every time a disabled person suicides. OD’s. or dies of a relatively minor disease,

I wonder how much the isolation has to do with it.

There are times the lesbian/gay community just shines. Like the festivals, especially the 1993 March on Washington.

At the 1931 San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Freedom Day Celebration, disabled lesbians and gay men enjoyed front row seating.

This was the first year celebration organizers designated a specific area for the disabled.(Rink Foto)

But then there are some strange gaps. The 1987 March on Washington was completely nonhelpful to the average disabled person.

Very few of the “alternative” magazines put themselves into accessible, affordable formats. None of the writers’ colonies

are accessible and Provincetown is just impossible.

A fairly newly disabled activist told me that the only way she keeps getting out is to focus on the good she’s doing day to

day.

And there is a lot of good happening to disabled people today. For years, we talked into the wind. We barely had a legal leg

on which to stand or sit. Now, thanks to the Americans with Disabilities Act, the general population is finally hearing us.

Sooner or later, the lesbian/gay communities will realize that, AIDS is not their only disability, and that access isn’t as

hard and costly as people believe.

I know you can do it. I’ve seen you. Just try talking, signing, or writing to us. Be patient and it will be worth it. I promise.

— CARRIE DEARBORN

It’s no accident that I am editing a newsletter for old lesbians and other women with the new title We Are VISIBLE.

Being invisible is one of many rages. First as an immigrant, then as working class, as a woman, as a wife, as a lesbian, and

now as old.

Sometimes I say to my old friends, “And what to do with the rage?” and they nod, shrug, or laugh at my audacity.

In the seventies, when the women’s movement was in full swing and I came out as a lesbian, one of my favorite statements was

“I can be angry at anything you care to speak to me about!” All the pent-up rage of years of sitting on myself in so many

aspects, shaping myself into the required image, holding in my stomach and my very being.

Eventually even the anger got stale and, like in so many of us, I tired of the struggle and wanted to love and be loved, to

save myself and the planet in a less aggressive way. The system eagerly awaited to incorporate me while twelve-step and other

programs enticed me with promises of peace and serenity.

Older lesbians and gay men march with Seniors Active in a Gay Environment (SAGE) in the 1985 Christopher Street Parade in

New York Cite. (Bettye Lane)

But it’s not working.

I’ve been sweating for twenty years—more, even. And why do I sweat? I am told it’s MENopause. I have often talked myself into

believing that it is connected with shame about my origins. Once, in my radical days, I researched the depletion of adrenaline

due to women’s constant fear and anxiety living in a patriarchy where she is constantly subjugated. At one time this gland

produced and excreted estrogen, thus naturally replacing the estrogen which no longer came from the ovaries. But the research

got lost somewhere in our efforts to take full responsibility for ourselves and quit blaming men. Am I sweating out my rage?

At the grand age of sixty-seven, I am still working a forty-hour-a-week job. I’d leave tomorrow if I had enough to live on.

The reward for ten years’ work is a pension of $650 a month—at the age of seventy. Guess I didn’t plan my finances right,

make the right investments, save more, work harder. So it’s my fault, isn’t it? Could this he a reason for my rage?

“Let this be a movement of brave old dykes led by brave old dykes. Age is a time of great wonder—a time when we have to hold,

with a fine balance, contradictory truths in our heads and give them equal weight: Old is scary but very exciting; chaotic

but self-Integrating; narrowing yet wider; weaker yet stronger than ever before.

“Let this be a movement of brave old dykes led by brave old dykes. Age is a time of great wonder—a time when we have to hold,

with a fine balance, contradictory truths in our heads and give them equal weight: Old is scary but very exciting; chaotic

but self-Integrating; narrowing yet wider; weaker yet stronger than ever before.

“It is we who must name the processes of our own aging. But just as we could not begin to say what it means to be a woman

until we had confronted the distortions of sexism and homophobia, so we cannot explore our aging without examining and confronting

ageism. it is the task that lies before us.”

BARBARA MACDONALD, OLD LESBIAN ACTIVIST

My work is with ordinary people, most of them living on what is called “welfare.” In Canada. It’s called pension, something

a person deserves after working all their lives, received without the humiliation of reducing themselves to abject poverty.

With that as a shadowy model, it’s small wonder that many of us go into old age with the ogre of poverty as companion. That

fear keeps ore separate from my companion lover as we both work out time in different parts of the country. Rage!

I’m angry about the new age salve that attempts to mute out my rage. If only I would meditate more, do affirmations, practice

yoga, give up chocolate and coffee, if only I would be a “real” vegetarian, grow my own vegetables, spend less, live in a

cabin in the county. It’s not that I don’t believe in these and try to do and be them. It’s that my rage is important too

and I want to be valued in this new age.

It keeps me on my toes around all important feminist issues and I am grateful for it. I don’t want it to be a contradiction

to compassion and love. For me it is the yin yang of staying a healthy happy old lesbian. I use the ocean as my guide. One

day she is so peaceful and calm I can see my face in her surface. The next she rages and roars with all the power she holds

inside. That is how I am too.

— VASHTE DOUBLEX, FROM SINISTER WISDOM

I had a dream a few nights ago that I was at my sister’s wedding. She got loads of praise; I was being completely ignored.

Finally, about halfway through the ceremony, I stood up and said, “I’m part of this family, too. Is anyone ever going to kvell over me?” Then I felt awful, full of shame and regret for disrupting the wedding. I couldn’t face myself, nor believe I had

done it. I woke up shaking. I felt that as a lesbian/bisexual I was not a good enough Jew, I was disloyal to my family and

my people. I believed the lie that a lesbian could not possibly be happy, and would have to be lonely and pitiful. Jews are

big on family and blood relations (I was often told only to trust mishpochah [family]). As an unmarried woman, I would never become an adult member of my I biological extended family.

I grew up mostly in New York with two immigrant parents, one who survived the Holocaust, the other one raised in England.

My father and his family come from Transylvania. The Holocaust was the elephant in the living room—never talked about, always

present. As a kid, I was hyperintellectual and overalert. I had many night-mares about being chased, murdered in my sleep,

shot at, going into hiding. I’ve noticed a lot of us Jews have some survival-based paranoia. Having one-third of our people

murdered in this century makes us a little edgy. Writing this article is terrifying. Exposure on such a large scale is the

opposite of my childhood lessons. My father, sitting at the dinner table, said, “ They can take everything away but they can’t

take away what’s up here,” tapping his temple. This is what I was taught: You have brains—use them, keep a low profile, never

let anyone know where you come from, i.e., that you’re a Jew.

Sometimes I feel a similar fear as a lesbian/bisexual woman. When I go to large gay parades or marches, I wonder if I’m the

only one who’s thinking Wow, what an easy opportunity to drop a bomb and wipe us out.… In different situations, I measure how out to be as a queer person (or as a Jew). My first day on a new job at a women’s

peace organization, I weighed heavily the pros and cons of placing a wall calendar above my desk. The theme of the calendar

was peace and justice, and the month of April showed a picture of one dykes-looking woman leaning on another in the Greek

Isles. All the other months featured sweet children’s drawings and pictures of doves. I decided to hang the calendar. It cost

me my job after the calendar roused the homophobic director. There are times I feel forced to prioritize myself as a Jew or

as a gay person. If I’m in a multicultural group and there are no other Jews, but there are other lesbians, I will speak out

as a Jew.

The two identities are completely intertwined, and I want to bring my full self everywhere. It’s in the Jewish lesbian/bisexual

community that I feel most at home. I sense that both Jews and queers have been forced by history and oppression to “take

care of our own.” I co-founded a Queer Minyan of lesbians, bisexuals, and gay men who meet monthly to celebrate Shabbat [Jewish

Sabbath]. We sing “Hineh matov umanayim shevet haqueer gam yachad.” It means “How good and sweet it is for us to be together.” The original has achim [brothers]. Something about replacing the Hebrew word for brothers with the contemporary English word queer stirs a feeling in the group. We are a Jewish queer family with tremendous love and support for each other. It is a blessing

to have a place where I can show myself freely.

I can pass as a non-Jew. I can also pass as a heterosexual. But every time I do, a part of me dies. At a meeting to plan a

huge multicultural ritual honoring ancestors, one man turned to me and said, “Why would you want to keep being Jewish? Why

not leave it behind with all the other patriarchal regressive belief systems?” And what my heart cried out was: I can’t not

be Jewish, just like I can’t change my short square hands or my long thin feet or my skinny legs. I can’t get over it by raising

my consciousness or changing my diet. I am a Jew. It’s the people I come from, it’s my ethnicity, my culture, it’s in my bones

and my blood. It’s the terror, the joy, the beauty, and the flavor of my thinking.

Non-Jews often reduce the Jewish people to the religion. But it is not only Judaism that makes me Jewish. It’s the mix of

culture and patterns, religion and stories. I identify with the long history of Jewish radicals, communists, socialists, and

progressives in this country and elsewhere. People like Emma Goldman, Adrienne Rich, Karl Marx, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, and

Si Kahn. We have a proud history of Jewish culture separate from the religion. The Yiddishkeit culture of Eastern Europe was

very rich and beautiful before it was destroyed by the Nazis. Now, fifty years later, lesbians in this country are among the

most active in nourishing the remaining seeds of Yiddishkeit. I am a part of a very old, diverse, and multicultural people.

We come from many countries, we speak many languages, we range in appearance from dark brown skin with kinky hair to light

skinned with blond hair. We may have been unwelcome, on borrowed time, in the countries we found ourselves in, but we were

deeply influenced by our surroundings. Since my immediate family came from Eastern Europe, the music and food and culture

I grew up with was infused with this part of the world. (One example: I thought borsht [red beet soup] was a Jewish dish until

a non-Jewish first-generation Russian friend of mine served it to me at a Christmas dinner!)

And in turn, as lesbians, we are reshaping what it means to he Jewish. I have a Jewish identity/spirituality that draws from parts of the religion

and mixes in other spiritual traditions that speak to me as a woman and lesbian. I think of the priestesses in the Temple

guarding the flame when I light my Shabbat candles. I dream of the Goddess’s hair when I eat challah [ritual braided egg bread].

— ALINA EVER

A few nights ago as I was getting out of my car at the top of my little hill in Los Angeles, I heard a terrible metal scream

that sent shivers down my spine. It was a battle cry, a mother’s wail, a dead man’s laugh; the sound of a shotgun.

Having grown up in the Pico-Union district of down-town, I know all too well the sound of ammunition in the nighttime sky,

but this one was so close that I jumped with the blast. A few seconds later I heard a ear’s leaping cry, like a dragster out

of the gate at the speedway. A small Toyota raced by me with four homeboys. The two in the backseat were still holding their

shotgun; out of the ear windows.

Later that night as I was working a pen toward paper, doing overtime on my poet duties, I decided to go down to my trusted

7-Eleven for one of those snacks that make me the last man on the totem pole at the gym. On the way down the hill I saw an

ambulance and the coroner’s truck at the site of where that bullet screamed and hit. It was the house on the block that makes

everyone uncomfortable. The one the neighbors talk about when they mention “property values.” The house where they park cars

on the lawn. A Spanish bungalow blasting Sunday afternoon FM stations with a backyard keg. The house where beautiful brown-skinned

shirtless boys with teardrop tattoos and shaved-head prison dos walk a fashion runway of “misfit.” Daring each other to lower

their baggy khakis and striped JC Penny boxers below the imaginary line of “acceptable.” Somewhere down toward desire. Giving

feisty chola girls and colored queer boys like me reason enough to still want to live in the bad neighborhoods where we grew

up.

I watched the body bag, all zipped up and ready for the morgue, where a veterana chola mama will identify next-of-kin as shooting victim number “we’ve lost count, don’t ask anymore.” I pass a number of

rod iron-windowed houses where old ladies are peeking through the kitchen curtains for a glimpse of this week’s tragedy. Heads

nod at the corner while housewives go hack inside to iron a viejo’s clothes for the next day’s commute. Oprah said it would be like this.

“Some queers like me come from or have sought social and cultural circumstances in which Independent teachers … whom some

call ‘crazy wisdom masters,’ are ‘on the loose.’ Their lives constantly challenge conventional wisdoms and ordinary morality,

eccentrically assisting in the process of understanding the play and transience of psychohistorical structures and conventions

rooted in history and in the psyches of individuals. Such eccentric teachings seem to empty the body and mind of crippling

biographical and cultural baggage as a necessary prerequisite to the development of understandings which may lie outside ordinary

human judgment, free of cultural blinders.”

“Some queers like me come from or have sought social and cultural circumstances in which Independent teachers … whom some

call ‘crazy wisdom masters,’ are ‘on the loose.’ Their lives constantly challenge conventional wisdoms and ordinary morality,

eccentrically assisting in the process of understanding the play and transience of psychohistorical structures and conventions

rooted in history and in the psyches of individuals. Such eccentric teachings seem to empty the body and mind of crippling

biographical and cultural baggage as a necessary prerequisite to the development of understandings which may lie outside ordinary

human judgment, free of cultural blinders.”

PITZER COLLEGE PROFESSOR LOURDES ARGUELLES, FROM “CRAZY WISDOM: MEMORIES OF A CUBAN QUEER” IN SISTERS, SEXPERTS AND QUEERS

I went off to 7-Eleven, standing there reading Noticias del Mundo, wondering what I could do. Feeling helpless, a bit traumatized, my urban dilemma started to feel like some had movie-of-the-week

and I decided to go home. As I was heading back up the hill I was convinced that I should drive by the shotgun house if only

to confront my fears about this situation and its occupants. Let’s not forget, they are my neighbors.

As I turned the corner I saw a faint glory of flickering fire-light. I slowed down and saw a pool of dried blood. Over the

traces of this once beating heart stood twelve candles in the shape of a cross. I was so nursed by this image. By this reminder

of what the living among us do. Someone was marking the loss. I knew I had to do something.

The next morning, as I was fighting with the urban commuters for the first chance at the carpool lane, I slowed down at the

bottom of the hill and saw the quiet candles flickering a small reminder of the previous night’s event. Next to the candles

and the pool of blood was a shopping cart and a small sign in modern-day Sanskrit, cholo writing, that spelled out the name

Eddie. Inside the cart were a pile of clothes, pictures, a baseball cap, some hangers, and shoes. Eddie in a nutshell.

Two Cuban American men enjoy a dance at a Dade Count, Florida gay watering hole in 1977. (Bettye Lane)

When I got to the corner, I did what my grandmother and I always did ever summer in Tijuana at the announcement of a death

in the colonias. I stopped at a flower shop and bought a small funeral wreath. I drove back and left it lying in front of the last drops

of Eddie. I don’t know if Eddie was an innocent drive-by victim or a violent motherfucker pissing on a territory he shouldn’t

have. I don’t care. Rack then, in Tijuana, buses fell over cliffs, jealous wives shot wandering husbands. a pack of coyotes

stole away a child, cows fell on you. Whatever the reason, we were always there. To mark the passing. It was our responsibility.

Our role.

In the queer community we mark the passing of our sisters and brothers because sometimes families don’t. We put up pictures

of our dead friends because sometimes we forget what they looked like before they got sick. We write about our dead artists

because sometimes we forget what they did. We grieve openly in front of murals and altars of memory because we see how much

we have lost. We say prayers for art works because that’s what families tend to throw away first.

I started to make the documentation of queer Latino artists who had died of AIDS part of my art, because whole bodies of work

became fragmented among collectors with no sense of what that work meant. This is what I give back to my community, my little

hillside block. A sense of memory. The what-used-to-be of life.

That night on my way home I was amazed at what had happened to our blood-soaked Silver Lake corner. A transformation had taken

place. Over thirty candles of various shapes and sizes were doing time illuminating the dead. Stacks of flowers piled on top

of each other gave off shadows from candlelight. Little cards lay on the sidewalk. Someone had taken an old junior high picture

of the dearly departed and made a large photocopy that hung over the shopping cart. This is what we give back to the community.

The pictures left behind. The melted candles. The rituals. A history.

I saw an old lady walking home from the market with two bags of groceries, and she stopped at the corner. She kneeled down

in front of the sidewalk altar and did a sign of the cross. She pulled a head of rosaries out of her purse and draped them

over the photocopy picture of that junior high school yearbook entry.

We remember you, Eddie. Whoever you are.

— LUIS ALFARO

I was living in the country, raising sheep, and publishing a magazine with other women in the community, gay and straight.

We had done an early issue on sexuality, where all of us wrote rather intimate and exposing pieces. (Because of editorial

decisions, the author’s names did not appear on the pieces themselves.) I was quite proud of my involvement with the magazine,

and had encouraged my entire family to get subscriptions to it. My parents were visiting when the sexuality issue came out.

One morning early, there was a knock on my door. There was my mother, holding the current issue, looking at me. “Sherry.”

she said in her Southern drawl. “Did you write this?” She pointed to the piece in which I had graphically described having

sex with my lover, eleven years my senior.

“Yes, I did,” I replied, trying not to sound tentative.

She looked at me. After several seconds, she asked,“All of this?”

What could I say? “Yes, all of it.”

Another pause. “Well. let’s not tell your father,” she said with a gleam in her eye. “Let’s see if he can figure it out.”

— SHERRY

My grandmother, Lydia, and my mother, Dolores, were both talking to me from their bathroom stalls in the Times Square movie

theater. I was washing butter from my bands at the sink and didn’t think it at all odd. The people in my family are always

talking; conversation is a life force in our existence.

To be a lesbian was part of who I was, like being left-handed—even when I’d slept with men. When my great-grandmother asked

me in the last days of her life if I would be marrying my college boyfriend I said yes, knowing I would not, knowing I was

a lesbian.

It seemed a fact that needed no expression. Even my first encounter with the word “bulldagger” was not charged with emotional

conflict. When I was a teen in the 1960s, my grandmother told a story about a particular building in our Boston neighborhood

that had gone to seed. She described the building’s past through the experience of a party she’d attended there thirty years

before. The best part of the evening had been a woman she’d met and danced with. Lydia had been a professional dancer and

singer on the black theater circuit; to dance with women was who she was. They’d danced, then the woman walked her home and

asked her out. I heard the delicacy my grandmother searched for even in her retelling of how she’d explained to the “bulldagger”

as she called her, that she liked her fine but she was more interested in men. I was struck with how careful my grandmother

had been to make it clear to that woman (and in effect to me) that there was no offense taken in her attentions, that she

just didn’t “go that way,” as they used to say. I was so happy at thirteen to have a word for what I knew myself to be. The

word was mysterious and curious, as if from a new language that used some other alphabet which left nothing to cling to when

touching its curves and crevices. But still, a word existed, and my grandmother was not flinching in using it. In fact, she’d

smiled at the good heart and good looks of the bulldagger who’d liked her.

Once I had the knowledge of a word and a sense of its importance to me, I didn’t feel the need to explain, confess, or define

my identity as a lesbian. The process of reclaiming my ethnic identity in this country was already all-consuming. Later, of

course, in moments of glorious self-righteousness, I did make declarations. But they were not usually ones I had to make.

Mostly they were a testing of the waters.

I need not pretend to be other than who I was. But did I need to declare it? During the holidays when I brought home best

friends or lovers my family always welcomed us warmly, clasping us to their magnificent bosoms. Yet there was always an element

of silence in our neighborhood, and surprisingly enough in our family, that was disturbing to me.

If the idea of cathedral weddings and station wagons held no appeal for me, the concept of an extended family was certainly

important. But my efforts were stunted by our inability to talk about the life I was creating for myself, for all of us. It

felt all the more foolish because I thought I knew how my family would react. I was confident they would respond with their

customary aplomb just as they had when I’d first had my hair cut as an Afro (which they hated) or when I brought home friends

who were vegetarians (which they found curious). Somewhere deep inside I think I believed that neither my grandmother nor

my mother would ever censure my choices. Neither had actually raised me; my great-grandmother had done that, and she had been

a steely barricade against encroachment on our personal freedoms and she’d never disapproved out loud of anything I’d done.

But it was not enough to have an unabashed admiration for these women. It was one thing to have pride in how they’d so graciously

survived in spite of the odds against them. It was something else to be standing in a Times Square movie theater faced with

the chance to say “it” out loud and risk the loss of their brilliant and benevolent smiles.

My mother had started reading the graffiti written on the wall of the bathroom stall. We hooted at each of her dramatic renderings.

Then she said (not breaking the rhythm, since we all know timing is everything). “Here’s one I haven’t seen before—‘DYKES

UNITE.’” There was that profound silence again, as if the frames of my life had ground to a halt. We were in a freeze-frame

and options played themselves out in my head in rapid succession: Say nothing? Say something? Say what?

I laughed and said, “Yeah, but have you seen the rubber stamp on rubber desk at home?”

“No,” said my mother with a slight bit of puzzlement. “What does it say?”

“I saw it.” my grandmother called out from her stall. “It says: ‘Lesbian Money’!”

“What?”

“Lesbian Money,” Lydia repeated.

“I just stamp it on my big bills,” I said tentatively, and we all screamed with laughter. The other woman at the sinks tried

to pretend we didn’t exist.

“I studied chests, arms, and thighs glistening with sweat, and the tricks light can play when reflecting off a mirrored ball.

That was the beginning. The beginning of feeling that the word ‘faggot’ did not accurately name the man I was or the man I

was aspiring to become. The beginning of thinking thoughts that started off with ‘I have nothing to be ashamed of…’ and ‘I

have a right to…’ The beginning of discarding the silence and the shame. The beginning of seeing the truth through all of

the lies.”

“I studied chests, arms, and thighs glistening with sweat, and the tricks light can play when reflecting off a mirrored ball.

That was the beginning. The beginning of feeling that the word ‘faggot’ did not accurately name the man I was or the man I

was aspiring to become. The beginning of thinking thoughts that started off with ‘I have nothing to be ashamed of…’ and ‘I

have a right to…’ The beginning of discarding the silence and the shame. The beginning of seeing the truth through all of

the lies.”

CHARLES HARPE, FROM “AT 36” IN BROTHER TO BROTHER

Since then there has been little discussion. There have been some moments of awkwardness, usually in social situations where

they feel uncertain. Although we have not explored the “it,” the shift in our relationship is clear. When I go home it is

with my lover and she is received as such. I was lucky. My family was as relieved as I to finally know who I was.

— JEWELLE GOMEZ, EXCERPTED FROM MAKING FACE, MAKING SOUL

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

The first Annual Deaf Lesbian and Gay Awareness Week was held in May 1994. Taking place in the San Francisco Bay Area, the

week-long celebration included workshops, readings from the first deaf gay and lesbian reader, Eyes of Desire, and a Deaf

Queer Pride Party at the Deaf Gay and Lesbian Center. The center is the first national organization run by and for gay and

lesbian deaf people, and not associated with a college or university.

September 19. Got rejected today at Christopher’s —looked at myself in the mirror and liked what I saw. Must have been the fact that I

was deaf that scared him off. So, what’s new?

October 7. Met someone at the gym today in the strangest way—may be a perfect example of my situation of not being able to hear. His

name’s Stan, and he’s from San Francisco. I was working out when I saw him and he noticed me. But after a few minutes at the

machines, I noticed he wasn’t looking at me anymore and that he was almost done. I beat him to the showers but he still ignored

me.… I asked him if he’d lost a towel. He never answered my question about the missing towel. Instead, he looked at me and

said quite clearly, “My God, you’re deaf!” He told me he’d come up behind me while I was doing an exercise and spoken to me.

I never answered him, so he put it off as New York snobbishness. Went to his hotel with him and had a marvelous time. Now

I wonder how many times have people come up behind me and given up when I’d not responded? How many of them thought of the

possibility I couldn’t hear them?

December 3. Someone asked me what it was like to be deaf. I asked the person who said it what it was like to be hearing. He couldn’t

answer. I’ve never been able to hear, so how could I explain the difference?

December 4. Met some straight deaf people who were shocked when I told them I was gay. They disapprove for an obvious reason—I won’t

bring any deaf children into the world. But there are other people who will maintain the heritage of deaf culture. I don’t

have that “primitive urge” to maintain the “tribe” of deaf people for future generations. It’s hard for me to identify with

much of the deaf community—it’s so varied—there are the differences along the lines of education, status, religion, race,

and sexual preference. The gay community has exactly the same differences!

“In my research of deaf gay men, I’ve asked this question of them: Suppose there are two candidates running for president,

the first one for rights of the handicapped and the second one supporting gay rights. All said they would rather vote for

the one supporting the rights of the handicapped than the one for gay rights. Which means the deaf gay person is more concerned

with deaf rights than with gay rights. This Is also true of us in the deaf community. We think of ourselves as gay first,

then deaf second; but In the hearing world, we think of our deafness first and our gayness second.”

“In my research of deaf gay men, I’ve asked this question of them: Suppose there are two candidates running for president,

the first one for rights of the handicapped and the second one supporting gay rights. All said they would rather vote for

the one supporting the rights of the handicapped than the one for gay rights. Which means the deaf gay person is more concerned

with deaf rights than with gay rights. This Is also true of us in the deaf community. We think of ourselves as gay first,

then deaf second; but In the hearing world, we think of our deafness first and our gayness second.”

TOM KANE, DEAF GAY ACTIVIST EXCERPTED FROM “MEN IN PINK SPACESUITS,” EYES OF DESIRE

January 3. Met a couple of deaf men from Washington, D.C. They were surprised I knew many hearing men, and they told me that I wasn’t

being fair. I shouldn’t be socializing with anybody but deaf people. I’d rather look at it this way—my life is in the world,

and I want to get involved with it as much as I can. For some deaf gay men, the world seems hostile because of the difficulty

communicating. One man even accused me of showing off my ability to interact with the hearing world. I told him it wasn’t

easy at all, but I wasn’t letting it prevent me from doing so. I relish the challenge.

— BRUCE HILBOK

When I say I am a Black Lesbian, I mean I am a woman whose primary focus of loving, physical as well as emotional, is directed

to women. It does not mean that I hate men. Far from it. The harshest attacks I have ever heard against Black men came from

those women who are intimately bound to them and cannot free themselves from a subservient and silent position. I would never

presume to speak about Black men the way I have heard some of my straight sisters talk about the men they are attached to.

And of course, that concerns me, because it reflects a situation of noncommunication in the heterosexual Black community that

is far more truly threatening than the existence of Black Lesbians.

What does this have to do with Black women organizing?

Kim Samsel (left) signs with Robin Ching in Baltimore, 1987. (§JEB)

I have heard it said—usually behind my back—that Black Lesbians are not normal. But what is normal in this deranged society

by which we are all trapped? I remember, and so do many of you, when being Black was considered not normal, when they talked about us in whispers, tried to paint us, lynch us, bleach us, ignore us, pretend we did not exist. We called

that racism.

I have heard it said that Black Lesbians are a threat to the Black family. But when 50 percent of children born to Black women

are born out of wedlock, and 30 percent of all Black families are headed by women without husbands, we need to broaden and

redefine what we mean by family.

I have heard it said that Black Lesbians will mean the death of the race. Yet Black lesbians bear children in exactly the

same way other women bear children, and a Lesbian household is simply another kind of family. Ask my son and daughter.

The terror of Black Lesbians is buried in that deep inner place where we have been taught to fear all difference—to kill it

or ignore it. Be assured: Loving women is not a communicable disease. You don’t catch it like the common cold. Yet the one

accusation that seems to render even the most vocal straight Black woman totally silent and ineffective is the suggestion

that she might be a Black Lesbian.

If someone says you’re Russian and you know you’re not, you don’t collapse into stunned silence. Even if someone calls you

a bigamist, or a childbeater, and you know you’re not, you don’t crumple into bits. You say it’s not true and keep on printing

the posters. But let anyone, particularly a Black man, accuse a straight Black woman of being a Black Lesbian, and right away

that sister becomes immobilized, as if that is the most horrible thing she could be, and must at all costs be proven false.

That is homophobia. It is a waste of woman energy, and it puts a terrible weapon into the hands of your enemies to be used

against you to silence you, to keep you docile and in line. It also serves to keep us isolated and apart.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Thirteen-year-old writer Malkia Cyril attended the Second National Black writers Conference in March 1988. Accompanied by

her mother, she had come especially to see Audre Lords, the only black lesbian she knew—and a role model for her. Malkia took

the microphone with Barbara Smith and Gail Lewis to share her happiness at discovering other black lesbians and role models.

She later said. “I’ve been waiting for a long time so that I could see a positive lesbian role model for myself to follow.

So I can continue the way I’ve been living, knowing it’s okay… knowing that it’s right.”

I have heard it said that Black Lesbians are not political, that we have not been and are not involved in the struggles of

Black people. But when I taught Black and Puerto Rican students writing at City College in the SEEK program in the sixties,

I was a Black Lesbian. I was a Black Lesbian when I helped organize and fight for the Black Studies Department of John Jay

College. And because I was fifteen years younger then and less sure of myself, at one crucial moment, I yielded to pressures

that said I should step back for a Black man even though I knew him to be a serious error of choice, and I did, and he was.

But I was a Black Lesbian then.

When my girlfriends and I went out into the car one July Fourth night after fireworks with cans of white spray paint and our

kids asleep in the backseat, one of us staying behind to keep the motor running and watch the kids while the other two worked

our way down the suburban New Jersey street, spraying white paint over the black jockey statues, and their little red jackets,

too, we were Black Lesbians.

When I drove through the Mississippi Delta to Jackson in 1968 with a group of Black students from Toughaloo, another car full

of redneck kids trying to bump us off the road all the way back into town, I was a Black Lesbian.

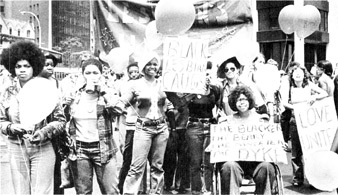

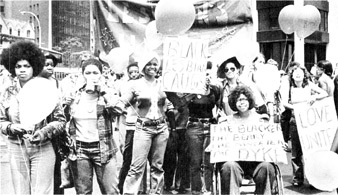

African American dykes marching together at the 1973 Christopher Street rally. (Bettye Lane)

When I weaned my daughter in 1963 to go to Washington in August to work in the coffee tents along with Lena Horne, making

coffee for the marshals because that was what most Black women did in the 1963 March on Washington, I was a Black Lesbian.

When I taught a poetry workshop at Toughaloo, a small Black college in Mississippi, where white rowdies shot up the edge of

the campus every night, and I felt the joy of seeing young Black poets find their voices and power through words in our mutual

growth, I was a Black Lesbian. And there are strong Black poets today who date their growth and awareness from those workshops.

When Yoli and I cooked curried chicken and beans and rice and took our extra blankets and pillows up the hill to the striking

students occupying buildings at City College in 1969, demanding open admissions and the right to an education, I was a Black

Lesbian. When I walked through the midnight hallways of Lehman College that same year, carrying Midol and Kotex pads for the

young Black radical women taking part in the action, and we tried to persuade them that their place in the revolution was

not ten paces behind Black men, that spreading their legs to the guys on the tables in the cafeteria was not a revolutionary

act no matter what the brothers said, I was a Black Lesbian. When I picketed for Welfare Mothers’ Rights, and against the

enforced sterilization of young Black girls, when I fought institutionalized racism in the New York City Schools, I was a

Black Lesbian.

But you did not know it because we did not identify ourselves, so now, you can say that Black Lesbians and Gay men have nothing

to do with the struggles of the Black Nation.

And I am not alone.

When you read the words of Langston Hughes you are reading the words of a Black Gay man. When you read the words of Alice

Dunbar-Nelson and Angelina Weld Grimke, poets of the Harlem Renaissance, you are reading the words of Black Lesbians. When

you listen to the life-affirming voices of Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, you are hearing Black Lesbian women. When you see the

plays and read the words of Lorraine Hansberry, you are reading the words of a woman who loved women deeply.

Today. Lesbians and Gay men are some of the most active and engaged members of Art Against Apartheid, a group that is making

visible and immediate our cultural responsibilities against the tragedy of South Africa. We have organizations such as the

National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays, Dykes Against Racism Everywhere, and Men of All Colors together, all of which

are committed to and engaged in antiracist activity.

Homophobia and heterosexism mean you allow your-selves to be robbed of the sisterhood and strength of Black lesbian women

because you are afraid of being called a Lesbian yourself. Yet we share so many concerns as Black women, so much work to he

done. The destruction of our Black children and the theft of young Black minds are joint urgencies. Black children shot down

or doped up on the streets of our cities are priorities for all of us. The fact of Black women’s blood flowing with grim regularity

in the streets and living rooms of Black communities is not a Black Lesbian rumor. It is a sad statistical truth. The fact

that there is a widening and dangerous lack of communication around our differences between Black women and men is not a Black

Lesbian plot. It is a reality that is starkly clarified as we see our young people become more and more uncaring of each other.