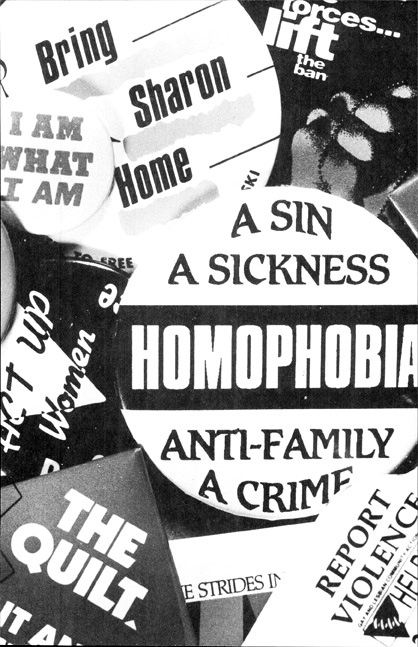

Queer. The word has many different meanings: Different. Odd. Strange. Out of place. We use queer to describe things that make us uncomfortable, things that don’t quite fit into the world as we have defined it. While many people, gay and straight, can and do accept much of what is lesbian and gay, there are some aspects of our lives that are controversial, that make people uncomfortable. There are certainly aspects to being gay that are difficult for many of us to understand and embrace. Curious is another definition of the word queer. And much of what is queer is also what piques our curiosity. This chapter is a nonthreatening look at both aspects of queer as it relates to the gay community, sort of a “Queer 101.”

“I think it’s okay that you’re gay, but why do you have to flaunt it?” is a comment most gay people have heard many times. Gay parades and marches are one way that gay and lesbian people make their presence felt publicly, and that makes many nongay people uncomfortable. It’s intellectually easy to accept that your cousin who lives in New Jersey is gay; it’s another thing when 200,000 gay people are marching through the center of town. But for those marching, there is no comparable experience. Having spent most of our lives in the minority, these events offer gay people a once-a-year opportunity to feel safe on the streets, surrounded by “our own kind.”

Gay or straight, the subject of sexuality also makes many people uncomfortable. People who challenge traditional conventions of gender—drag queens, leather dykes, bisexuals, transgendered people, lesbians into butch/femme—are all in some way toying with society’s long-held views of what makes a person masculine or feminine. These are hard concepts to get a handle on. At the same time, we are all curious about those whose identities are different from our own.

If the topic of sexuality makes people nervous, then the topic of sex can send them out the door. It’s hard for some people to accept, but, yes, Virginia, gay people do have sex. In the push to gain acceptance, discussions of sex are often neglected; forgotten is that for many of the Stonewall-era gay activists, “gay liberation” was seen in part as a movement for “sexual liberation.” For many gay and lesbian people, this is still primary. In this section we talk about many aspects of sex and the community, including leather, gay porn, and lesbian erotica.

Finally, despite the notion that gay and lesbian people are “just like everyone else,” we have developed our own styles and ways of dressing. These “codes,” along with the “gaydar” most gay people appear to have been born with, have evolved over time to help us find each other. Some of the icons, fashions, and symbols of our movement are found at the end of this chapter.

The heart of queer is basic: It’s recognizing one’s own uniqueness in society and celebrating it. Queer is understanding that it is our differences that make life exciting, that allow us to grow as a community, that challenge us to better appreciate those around us. Queers understand that while it is sometimes difficult and frustrating, difference is an opportunity for progress, not simply a thing to “get over.” It is through the differences that we can discover our common ground, and create a safe place for everyone to express their opinions, passions, and concerns.

This seems to he something that the “gay-not-queer” crowd overlooks. They see difference as a problem to be solved or ignored. One of the arguments against recognition of lesbians and gay men has been that being gay is a “bedroom issue,” that is, that our sexuality has nothing to do with the larger political world. Difference, to gay-not-queers, is a bed-room issue, as if it has nothing to do with political struggle or even cooperation between communities in day-to-day life. They talk a lot about emphasizing similarities rather than focusing on difference, as if the two things are mutually exclusive. The “gay-not-queer” world pictures difference as five people screaming at each other in different languages, with no one listening to or understanding anyone else. Queer vision recognizes that only through listening to these different languages can we build a common vocabulary.

Being queer means being comfortable with having a spotlight, even a bull’s-eye, directly on one’s chest where it cannot be ignored. If you accept the responsibility of being queer, you can’t (and won’t) be stock for the soup in the fantasy “melting pot” of America. We’re queer as hell, and frankly, that’s a relief. We want to be different. We love being different—and it’s a privilege we’re not willing to give up. Not for “equal rights,” or “acceptance,” or to make being queer more palatable to the homophobic tongue.

And the reality is, even if some people don’t want to be “different,” we are different, because the heterosexual world, which holds the power, sees us as such. As long as one is gay, lesbian, bisexual, and/or transgendered, one is “queer.” Gay men, lesbians, bisexuals, transgendered people, and everything in between cannot afford to blend into anything.

Gay-not-queers seek to deny people they consider “controversial” access to our movement. Yet within the “gay and lesbian” community, there are bisexuals and transgendered people. Many queers are ostracized or made invisible by their biological families. How dare any gay man or lesbian propose that we kick out or conceal the members of our family who don’t easily fit under the arbitrary umbrella of gay/lesbian?

Being queer isn’t about eliminating our insecurities about difference but the hostility toward it. Queers recognize that while acceptance of difference is not always comfortable, it is a valuable tool through which we can enrich and strengthen ourselves both individually and as a community.

— ARWYN MOORE AND DON ROMESBURG

“It’s a lot easier to see the center from the margins than it is to see the margins from the center.”

“It’s a lot easier to see the center from the margins than it is to see the margins from the center.”

OVERHEAD AT A LESBIAN, GAY, AND BISEXUAL STUDENT UNION MEETING AT THE CLAREMONT COLLEGES, CLAREMONT, CALIFORNIA

I don’t think queer is a fundamentally bad word. Queer is a fine word to describe things that are odd, out of the ordinary, or strange. Queer also has a history and confrontational quality about it that makes it ideal for militant political slogans like “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it,” and for the name of out-front groups like Queer Nation and Queer Action.

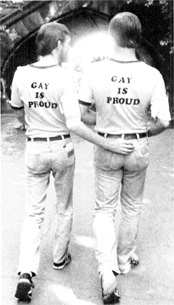

Two men take an out and proud walk together in New York City (1981). (Bettye Lane)

Some gay and lesbian people also find queer a fun and playful word to use among friends the same way they use fag and dyke. And I can hardly object to those homosexual men and women who choose to identify themselves as queer and align themselves with the latest wave of a forty-five-year old gay rights movement. But queer is not my word. Not because I’m an old fogey who can’t get with the new program and the latest language. Queer is not my word because it does not define who I am or represent what I believe in.

One of the claims I’ve heard made for queer is that it’s an inclusive word, embracing all kinds of people. It eliminates the need for naming a long list of groups to describe our movement, as in “gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, transvestite,” and so forth. But as a gay man, I’m not all those things. I’m a man who feels sexually attracted to people of the same gender.

As a gay man, I don’t want to be grouped under the all-encompassing umbrella of queer. I’m not even all that comfortable being grouped with bisexuals, let alone transsexuals, transvestites, and queer straights. Not because I have anything against these groups or don’t support their quests for equal rights, acceptance, and understanding—in fact, I do—but because we have different lives, face different challenges, and don’t necessarily share the same aspirations.

I have no desire to set myself apart from the main-stream or to carve a new path. Of course, as a gay man, I’m different from someone who grew up straight. And it’s important to recognize that difference and understand how that difference affects who I am. But I’d rather emphasize what I have in common with other people than focus on the differences. The last thing I want to do is institutionalize that difference by defining myself with a word and a political philosophy that set me outside the mainstream.

My approach to gay rights does not lead to revolutionary change in attitudes toward gay people, and it can be frustratingly slow. But it leads to the kind of evolutionary change that I believe will one day make it possible for gay men and lesbians to live without fear of rejection and discrimination, a day when we are no longer considered “the other” or “odd” or “queer.”

—ERIC MARCUS

From the moment a child is born, people begin asking, “Is it a boy or a girl?” That child is then raised to become a heterosexual woman or man. These two genders, which many people understand as set in stone as the only two genders, are determined in a variety of ways. From the time a child is born, society will aggressively regulate its journey toward a gendered self.

In the hospital, we can tell whether the child has a penis (which would indicate “boy”) or a vagina (which would indicate “girl”). The boy is wrapped in a blue swath, while the girl is wrapped in pink. These colors are the first step toward the social aspects of gender. But gender is much more than just biology. Once the child comes home from the hospital, parents and society begin training it to believe that girls are soft, emotional, and sensitive while boys are aggressive, tough, and rational. Girls are encouraged to desire lacy things and dolls and boys are supposed to like sports and trucks. As the child grows older, the rules of desire extend to sexual attraction, and boys are understood to be sexually attracted to girls and vice versa.

But many people fail to fall into these two genders, a strict two-piece set of “male” and “female” biology, behavior, and desire. For those people, these definitions are limitations, or, as JoAnn Loulan puts it, a “gender jail.” For those of us who grow up to be homosexual, bisexual, or transgendered, our journey toward a gendered self is a confusing and ambiguous road.

Loulan explains, “Many lesbians grow up identifying not as boys, but with boys. These girls want to do what the boys do and dress as the boys dress. And while these girls know that they aren’t actually boys, they only see two alternatives: male or female. If they are not girls, they must be boys. But they are not boys. From the time of that realization, as painful and alienating as it is, these young lesbians become gender outlaws. Residing in the netherlands of neither-nor, they begin to explore what it means to be something else entirely. In doing so, they create new genders.

Many gay and transgendered men also grow up with a sense of being a “neither-nor.” Some gay men respond to this ambiguity by attempting to diminish the difference between their sense of gendered self and the societal sense of “male.” They try to resolve the issue by accepting most of the “rules,” by being “masculine” and rational, but with a twist: They like to sleep with other men. As Loulan says, “The real issue of gender is about who has sex with who and how: who puts what appendage into what orifice.” Even while trying to accommodate the gender norms, these men inadvertently create yet another gender. Other gay men play with gender in a variety of ways, from drag to leather to hypermasculinity.

So what is gender? “Gender” is defined in Webster’s Dictionary as a colloquial or informal word used to describe one’s sex. But the words are anything but informal. The proscribed choices are two: “male” or “female.” Loulan says that this feminine/masculine paradigm literally stops us from being able to describe who we are: “What if, instead of two genders, there are more? What if there are endless ways of being female, and infinite ways of being male?”

The reality is that most people, including many lesbians and gay men, are threatened by the possible worlds Loulan’s questions suggest. Few things, after all, make people more uncomfortable than being unable to discern the gender of a person we’re talking with, either face-to-face or on the phone. It’s even more upsetting when men become women and women become men. Transsexuals are truly on the gender front lines. People hate transsexuals because they are confusing to those of us that feel we are safe within gender limits. Even in on-line computer conversations, one of the first things people want to know is: “Male or female?”

Perhaps, as Loulan says, “Homophobia can really be looked at as genderphobia.”

She continues, “Imagine a world in which you get to choose whatever you want to wear. You get to choose however you want to play, and what you do for work. You don’t worry about who you are having sex with or who you want to marry. All of the concerns about homosexuality, bisexuality, transsexuality, and heterosexuality are gone. A world where gender is seen as a combination of genetics, choice, and culture, and is ultimately irrelevant.”

Truly, love (and hate) is a many-gendered thing. In this section, we explore the idea that, within a galaxy of gendered selves, “male” and “female” are not the only stars. And to wonder, as Loulan does, whether “in our scramble to prove that we are women and men, we stumble right past our opportunity to claim more honest gender identities.” To do that, we may need to move beyond the discussion of male/female altogether.

…if you were of the other sex? That is, if you are a lesbian, would you be a gay man if you were a male? Conversely, if you are a gay man, do you think that you would be a lesbian if you were female? One of the editors ran across this discussion on Gaynet, one of the Internet gay bulletin boards. This thread had garnered more than thirty-five responses. Here are some of those responses:

If I were a woman I wouldn’t *be* me, so I can’t even attempt to guess at *anything* about this not-me female, much less her sexuality. Well, OK—I do think she’d wear *faaabulous* shoes, whatever *that* means.…

Rod, San Francisco

• • • •

Forget about the shoes—I would be a *whore*.

Greg

• • • •

Ahah! A chance, once again, to tell the tale of an acquaintance of some years ago:

I was at a dance club in 1965 and this beautiful person walked in with some dykes. After ogling what I thought was a beautiful young man, I was politely informed that she was not. She was a mechanic and a lesbian (which immediately stirred my suppressed bi side).

I lost track of this person till a number of years later when I met *him* tending bar. Since he now had a rather nice moustache, I was puzzled. He told me of his gender problems since a very young age and his change from female to male. I (very stupidly) asked why he was tending bar in a gay bar and he said, “because I’m gay, of course.”

Over the years, we discussed many things, including intimacies of the operations (not that that matters). One of the things that we both discussed often was the curious fact that, as a woman, he enjoyed the company of women and as a male, males.

The sum of all this?? I somehow feel that homosexual is homosexual and has little to do with being transexual or with the person’s sex.

Doug, still fascinated by the whole concept

P.S. I *definitely* would be a lesbian if I were female. No question about that at all. I have pondered this question since the mid 60s and have often wished (I don’t know why) I *were* female just so I *could* be.

• • • •

I adore women, and that’s about the sum of it.

Melinda, Ithaca, New York

• • • •

I honestly don’t know. I would think I would be attracted to men no matter what. I certainly know that, if I woke up female tomorrow (god forbid), I’d still be attracted to men. No doubt about that.

Trey/Nothing Wrong With Being Female, But I’m Happy To Be Male—Asheville, OR

• • • •

About 25 years ago I figured out that if I had been born a man I would have been gay. While this might be due to a failure of imagination (I simply can’t imagine not finding men attractive) I suspect it is something deeper.

Emily

• • • •

Hmm, this is a real brain twister. Well, I suppose I still wouldn’t be able to shop, or color coordinate my clothing, or know how to cook. So nothing would change.

I guess I’d have to do just what I do now. Even though I’d be a woman, I’d have to marry a gay man to cook, clean, tell me what to wear, and be there with a shoulder to cry on.

Face it, not many straight men would be able to meet my needs. :)

Chuck, Berkeley, CA

• • • •

What fascinates me is that someone could actually think that sexual preference could actually change when gender changes.

Do you mean if I was born a man or I became a man? If I were to wake up tomorrow and *gasp* discovered I had a dick that was actually attached (perish the thought) I would still adore women lesbians in particular. (Though, I guess it would be hard to get a date in my circle of friends.) I would probably become a <insert favorite term for str8 man who hangs out with dykes>. I think that if I were born male I would be a str8 male.

But sitting here thinking about it, I wouldn’t want to be anything but a lesbian. I think, given a choice, I would choose duke every time.

It is not just about loving women per se. It is about *women* loving women.

Sammie, Athens, GA

• • • •

If I had a sex change, and had the choice of having a straight man or a lesbian woman as a partner, I think I would he most unlikely to put tip with the sort of non-sense that straight men dish out in general (and not only to women). Call me a possible-worlds political lesbian, if you wish.

Keith, Toronto

• • • •

OGod yes, I *definitely* would be a lesbian if I were female. Anything rather than straight men (but I would be into strap-ons).

Dylan, Bellingham, WA

Sexuality runs along a continuum. It is not a static “thing” but rather a process that can flow, changing throughout our lifetime. Bisexuality falls along this continuum. As Boston bisexual activist Robyn Ochs says, bisexuality is the “potential for being sexually and/or romantically involved with members of either gender.”

MYTH: Bisexuals are promiscuous/swingers.

TRUTH: Bisexual people have a range of sexual behaviors. Some have multiple partners; some have one partner; some go through partnerless periods. Promiscuity is no more prevalent in the bisexual population than in other groups of people.

MYTH: Bisexuals are equally attracted to both sexes.

TRUTH: Bisexuals tend to favor either the same or the opposite sex, while recognizing their attraction to both genders.

MYTH: Bisexual means having concurrent lovers of both genders.

TRUTH: Bisexual simply means the potential for involvement with either gender. This may mean sexually, emotionally, in reality, or fantasy. Some bisexual people may have concurrent lovers: others may relate to different genders at various time periods. Most bisexuals do not need to see both genders in order to feel fulfilled.

MYTH: Bisexuals cannot be monogamous.

TRUTH: Bisexuality is a sexual orientation. It is independent of a lifestyle of monogamy or nonmonogamy. Bisexuals are as capable as anyone of making a long-term monogamous commitment to a partner they love. Bisexuals live a variety of lifestyles, as do gays and heterosexuals.

MYTH: Bisexuals are denying their lesbianism or gayness.

TRUTH: Bisexuality is a legitimate sexual orientation that incorporates gayness. Most bisexuals consider themselves part of the generic term “gay.” Many are quite active in the gay community, both socially and politically. Some of us use terms such as “bisexual lesbian” to increase our visibility on both issues.

MYTH: Bisexuals are in “transition.”

TRUTH: Some people go through a transitional period of bisexuality on their way to adopting a lesbian/gay or heterosexual identity. For many others, bisexuality remains a long-term orientation. Indeed, we are finding that homosexuality may be a transitional phase in the coming-out process for bisexual people.

MYTH: Bisexuals spread AIDS to lesbian and heterosexual communities.

TRUTH: This myth legitimizes discrimination against bisexuals. The label “bisexual” simply refers to sexual orientation. It says nothing about sexual behavior. AIDS occurs in people of all sexual orientations. AIDS is contracted through unsafe sexual practices, shared needles, and contaminated blood transfusions. Sexual orientation does not “cause” AIDS.

MYTH: Bisexuals are confused about their sexuality.

TRUTH: It is natural for both bisexuals and gays to go through a period of confusion in the coming-out process. When you are an oppressed people and are constantly told that you don’t exist, confusion is an appropriate reaction until you come out to yourself and find a supportive environment.

MYTH: Bisexuals can hide in the heterosexual community when the going gets tough.

TRUTH: To “pass” for straight and deny your bisexuality is just as painful and damaging for a bisexual as it is for someone gay. Bisexuals are not heterosexual and we do not identify as heterosexual.

MYTH: Bisexuals are not gay.

TRUTH: We are part of the generic definition of gay. Nongays lump us all together. Bisexuals have lost their jobs and suffer the same legal discrimination as other gays.

MYTH: Bisexual women will dump you for a man.

TRUTH: Women who are uncomfortable or confused about their same-sex attraction may use the bisexual label. True bisexuals acknowledge both their same-sex and opposite-sex attraction. Both bisexuals and gays are capable of going back into the closet. People who are unable to make commitments may use a person of either gender to leave a relationship.

It is important to remember that bisexual, gay, lesbian, and heterosexual are labels created by a homophobic, biphobic, heterosexist society to separate and alienate us from each other. We are all unique; we don’t fit into neat little categories. We sometimes need to use these labels for political reasons and to increase our visibilities. Our sexual esteem is facilitated by acknowledging and accepting the differences and seeing the beauty in our diversity.

—DANAHY SHARONROSE

I am bisexual. I am a lesbian. I am a bi-identified lesbian. I am a lesbian-identified bisexual. I am a lesbian who has sex with men. I am confused. I am all these things, given the day of the week and who wants to know.

A large part of this society’s social relation problem is its constant need to pigeonhole people. I thought I would escape that when I took refuge in the world of gay men and lesbians, who understand the repressive, limiting categories of the heterosexual world and would not impose their own. On the contrary. Gay men and lesbians have generated more categories among themselves than you can keep track of. Regarding bisexuality, however, the gay community often practices discrimination by omission. “Bisexuality” isn’t even considered a legitimate category; it’s some strange limbo between straight and gay that eventually has to dissolve into one or the other.

It’s as though the same school of thought on bisexuality exists among gay men and lesbians as exists among many heterosexuals toward gay men and lesbians—that our sexuality is a choice. I sense resentment from gay people who believe I can “pass” as straight and therefore have no claim to the gay community. Like people are saying, If you all can sleep with either men or women, why not just pick one, so you can either take your proper place among us, or be cast back into the abyss of heterosexuality?

If that’s the case, I’d rather be part of the queer community than the gay community. A distinct difference exists between the two. “Gay” is a sexuality, while “queer” is a sensibility. I know many gay people who are not queer. Queer is defined as outside the mainstream, anti-status quo, mentioning nothing about sexuality or emotionality. It is a willingness to be open to things that others shy away from, including but not exclusively same-gender sex. Even very hip straight people (emphasis on very) can have certain queer sensibilities, though they may never be gay. Gay men and lesbians who choose to embrace the outsider identity as a means of unity and empowerment ought to think about that. A friend of mine once said, “I don’t know what a queer is, but I know we’re not like everyone else.”

Westernized society has socialized us, straight and gay alike, to pair ourselves with genders, as opposed to personalities and spiritualities. We commit the fallacy of defining sexualities in terms of the sex act, because it is the easiest level to grasp. What is a woman who has sex with men but falls in love only with other women? What is a man who finds himself attracted to a male-to-female transsexual? The labels we attach reveal how we prioritize two definitions of sexuality: sex then emotion, or emotion then sex? The emotional and spiritual connections are often disregarded in place of who people have sex with. For me, bisexuality reaches beyond the physical, beyond the genital, where the walls of gender fade into the all-inclusive “human species.”

—ARWYN MOORE

While rooted in the past, butch/femme is not a thing of the past. Today, many lesbians are reclaiming their “butch” and “femme” selves and are finding that, among other things, these roles add an erotic dynamic to their relationships. But even the definition of butch/femme changes over time. And if we had fifteen words for genders, who knows how we would define our sexuality? So what is this thing called butch/femme?

Here is some of what butch/femme is not:

• Butch/femme is not about who is “top” and who is “bottom.”

• Butch/femme is not about being male and female.

• Butch/femme is not about playing husband and wife.

• Butch/femme is not about who earns the money and who spends it.

• Butch/femme is not about who makes love to whom.

• Butch/femme is not about who makes the decisions and who doesn’t.

• Butch/femme is not about passing for straight.

• Butch/femme is not about imitating heterosexual relationships.

The harder task comes in trying to define exactly what butch/femme is. Can straight women be butch? Can men be femme? Didn’t we all fight for years to eliminate rules (and roles) altogether? Does everyone fall into one category or the other?

Here is some of what butch/femme is:

• Butch/femme is about clothes and image.

• Butch/femme is about self-perception.

• Butch/femme is about redefining what it means to be a woman.

• Butch/femme is about femininity and masculinity.

• Butch/femme is about sexual dynamics.

• Butch/femme is about role playing.

• Butch/femme is about gender.

Joan Nestle, who defines herself as “a femme who came out in the 1950s,” attempts in The Persistent Desire to define butch/femme:

In the most basic terms, butch-femme means a way of looking, loving, and living that can be expressed by individuals, couples, or a community.… Butch-femme relationships, as I experienced them, were complex erotic and social statements, not phony heterosexual replicas. They were filled deeply with the language of stance, dress, gesture, love, courage, and autonomy.

From a more recent perspective, here are two women on butch/femme from “Debate #1” in The Lesbian Erotic Dance by JoAnn Loulan:

Part of identifying as butch stems from a desire to defend, protect, and defy the traditional feminine stereotype. All of these verbs imply a reaction to the world. Being butch to me to a large degree means reacting to the world. A large part of identifying as femme stems from a desire to create, empathize, and become the woman (femininity and all) inside us. Therefore identifying as femme is more of an initial action—not passive at all.

There are also women who identify with one role and are perceived to be the other. These lesbians are often referred to as butchy/femmes or femmy/butches.

I was putting on a new toilet seat—should be easy, right—just two screws—of course not. So I’m under the toilet trying to get these goddamned fucking corroded screws loose. My young son is watching all this. I say, “It’s sure a bitch being butch.” He looks at me in confusion and says, “Mom. I thought your girlfriend was butch.”

—from Debate #2 in The Lesbian Erotic Dance

(Jane Caminos)

Of course, for every lesbian who says she relates to the terms “butch” and “femme” there is another who claims “androgynous” as her self-description. And while self-definition is the most essential part of claiming our lesbian selves, even those who don’t identify themselves as butch or femme do have clear ideas about others. When Joanne Loulan talks to lesbians around the country, she will often get a woman to come on stage who says she is neither, and “let the audience decide.” And a roomful of lesbians, often 200 or more, who have never laid eyes on the woman, will always overwhelmingly choose one label or the other, before the woman has even opened her mouth.

—LYNN WITT

Transsexuals are a diverse group. For some, it’s important to disconnect totally from their past and lead a new life, telling practically no one. And then there are those who consider themselves neither gender, or a blend, regardless of the degree of their physical transition. Just as it’s important to have one’s sexual orientation acknowledged and accepted by the outside world, it is appreciated when one addresses a transsexual and refers to him or her with the pronoun of the gender presented by that person.

MYTH: Transsexuals just need to learn to be comfortable with the bodies they were born into.

TRUTH: Many of us spend years in therapy trying to adjust to the bodies we’re in. Sometimes we try to hide traces of our transgender issues by overcompensating the behavior of our assigned gender. By the time we start taking steps to change our bodies, this is literally the last resort. Few people question getting a facelift or breast implants to make a person feel more comfortable, but when gender is involved there’s a double standard. Physical adjustments aside, learning how to live in a role for which we haven’t been trained is challenging. Imagine going to a foreign country where you don’t know the language but you’ve got to act as if you do.

MYTH: FTMs (female-to-male transsexuals) become men to gain male privilege.

TRUTH: I have come across many people who are confused about why a man would become a woman, but at the same time think they know why a woman would become a man. It is often assumed that it has to do with having access to the opportunities that men have, like getting a better job. Historically, when women “passed” as men, it’s possibly true that they wanted more opportunity, but has anyone considered that maybe they also felt their true gender identity was male? It takes a lot more than just wanting a better job to cross over and live in a new gender role.

MYTH: Transsexuals can’t deal with their true homosexuality, so they change gender to lead heterosexual lives.

TRUTH: Gender identity and sexual orientation are separate issues. About half of MTFs (male-to-females) end up as lesbians, and among FTMs, there are more and more now identifying themselves as bisexual or gay. Some MTFs were gay men and now find themselves interested in women, and there are quite a number of FTMs who were lesbians and now identify as gay men. When going through a gender change, sexuality can be very fluid, and you never really know how you’re going to turn out.

MYTH: There are many more male-to-females than female-to-males.

TRUTH: Current statistics say it’s about 50/50.

MYTH: There is an increasing number of FTMs because there is no room in the lesbian community to be “butch.”

TRUTH: I have never heard of any FTM who made his change because of acceptance—or lack of it—from an outside community. It’s what goes on inside, how one feels in one’s body, and whom one sees in the mirror.

MYTH: The gender change happens when you have the “operation.”

TRUTH: “Have you had the operation yet.” is the classic “talk-show” line—as if you go to sleep a man, have an operation, and suddenly wake up as a woman. It takes about five years to get comfortable living as the new gender. Internally, the transition is ongoing. For most transsexuals the change really starts when they realize they need to change their body. The biggest changes are psychological. Within a three-month period, I had between fifty and seventy-five dreams about a gender change. Finally it sunk in that I needed to do something about it. Starting hormones triggers the most dramatic physical and emotional changes that take place during the first year. If you can imagine, your body has been receiving a certain set of signals for most of your life and then suddenly it starts getting a whole new set of messages. It takes time to shift gears. The next step might be surgery. Some transsexuals, for a variety of different reasons, don’t have surgery. For those of us who do, it might consist of a series of surgeries, (i.e., for FTMs, chest and then genital) several years apart.

MYTH: Masculinity and femininity can he expressed through whatever body one is in.

TRUTH: I often wonder why it is that we ascribe “male” to one set of behaviors and “female” to another. Ultimately I believe we have access to all of it. For transsexuals, however, it’s a visceral experience along with the compelling desire to change the body to more closely reflect the psyche. For some, it is absolutely necessary to transform completely on a physical level. For others, not. There are many possiblities and ways to express gender. I feel it’s important that we find what works for us as individuals and, at the same time, respect the choices that others make for themselves.

—DAVID HARRISON

“Prohibido la entrada a hombres vestidos de mujer porque carecemos de un baño para personas de tercer sex.” (“Men dressed

as women are prohibited because we don’t have a bathroom for persons of the third sex.”)

“Prohibido la entrada a hombres vestidos de mujer porque carecemos de un baño para personas de tercer sex.” (“Men dressed

as women are prohibited because we don’t have a bathroom for persons of the third sex.”)

SIGN AT THE FLAMINGO NIGHTCLUB IN REDWOOD CITY, CALIFORNIA, WHICH IS POPULAR WITH LATINOS

The alliance between the gay/lesbian and transgender communities is characterized by suspicion and misunderstanding on both sides. In many ways, it is the age-old story of an enfranchised group overlooking the needs of and actively excluding a less empowered group.

Of course, a considerable number of gay men and lesbians are sensitive toward transgendered persons and our plight. But others do not see and are often totally unaware of the larger transgender community, which is separate and distinct from the gay community. They don’t understand the diversity of the transgender community, and they certainly give little or no thought to the advantages of working together. Consequently, they rarely think of transgendered persons when affirming their own rights to serve in the military, to love whomever they please, and to work in discrimination-free settings.

But there is much more going on than mere indifference. There is a pervasive distrust of, antagonism toward, and even hatred of transgendered persons. A few gay men and lesbians seem determined to mandate us out of existence. They deliberately misuse pronouns, force transsexual persons out of gay and lesbian events, and on more than one occasion have been physically violent toward transsexual persons.

If the levels of understanding and attitudes of many gay men and lesbians toward transgendered persons can be characterized as ignorant, indifferent, embarrassed, or hostile, it becomes puzzling how and why the gay community has accepted transgender behavior to the extent that it has. Female impersonation is frequent at bars and parties, and many valued members of the community have gender presentations that vary far from the usual gender stereotypes. But acceptance of the idea of transgender is partial and sometimes grudging, resulting from ignorance by the gay/lesbian community that many in their community are transgendered.

This has resulted in what I call Gay Imperialism, in which the accomplishments and the very identities of transgendered persons are collapsed into the gay community. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is Billy Tipton.

Tipton was an accomplished jazz musician, a husband, and father of two adopted sons. After his death in 1989, it was revealed that he was biologically a woman. Marjorie Garber has written elegantly about Tipton in her book Vested Interests. She points out that the facts of Tipton’s life make no sense except when looked at in a transgendered light. His life was much more than a means to express himself via his music, and much more than a way to live a lesbian relationship. Neither his wife nor his sons were aware that he did not have male genitalia. He was a husband and a father to them and a man to his neighbors and fellow musicians; he was a woman only to the press and the gay/lesbian community, both of which claimed him and exploited him after he was conveniently dead.

Gay scholars have similarly exploited transgendered persons, even while specifically writing about them. In books about transgendered two-spirited American Indians, some scholars look at their subjects through gay-colored spectacles. It’s true that the sexual orientation of many and perhaps even most two-spirit people was to those of the same biological sex, but the two-spirit people are also, with equal if not greater profundity, transgendered. Gay scholars have interpreted two-spirit people from a gay perspective, even as heterosexual anthropologists have interpreted homosexual behavior in various cultures from their own point of view.

With its newly found voice, the transgender community will no longer tolerate such colonization by the gay community. People like Billy Tipton, Radclyffe Hall, and Joan of Arc are being reclaimed as transgendered—queer, but not gay. And it’s clear that it is a reclamation and not a revision, for they were stolen from the transgendered community. And make no mistake: The murmur of today will be a roar tomorrow.

The gay/lesbian and transgender communities have much to learn from each other. The transgender community is eager for discourse. It has much to learn about politics, self-discovery, and self-acceptance from the gay/lesbian community. And the gay/lesbian community must come to understand that the voices of transgendered persons will forever after be in their ears.

It’s a marvelous opportunity for both communities. Here’s hoping that the cannons will be pointed outward, toward those who would deny “queers”—all of them, transgendered or gay—the right to live, and not inward, toward those who are more like us than we care to think.

—DALLAS DENNY

“When you think of a bombshell, you think of Monroe or Mansfield, you don’t think of a 300-pound man. People like to be shocked.”

“When you think of a bombshell, you think of Monroe or Mansfield, you don’t think of a 300-pound man. People like to be shocked.”

DIVINE, ACTOR AND BLOND BOMBSHELL

The radical drag underground. The Wigstock generation. Drag post-moderne. Whatever it’s called, there is a new generation of drag performers who have no desire to coddle their audience with the umpteenth rendition of Marilyn. Spurred on by both homophobia and AIDSphobia, this drag is fresh, fierce, and fighting mad.

But not all drag performers see false eyelash to false eyelash on the activist power of donning a dress. There are those performers, both male and female, who use cross-gender guise to bring attention to their political forum and those who do it strictly for entertainment value.

While Atlanta drag performer Lurleen and Los Angeles drag Vaginal Creme Davis are out on the front lines, involved in groups such as ACT UP, and giving benefit performances for the fight against AIDS, others, such as John Epperson as Lypsinka, see their roles simply as entertainers.

“AIDS has forced gay people to think about who we are and what our relationship with straight society really is,” says the strawberry-blond Lurleen. “It’s hard to be an apolitical person these days. I’m no strident Marxist, but when there is a reactionary government in power, it’s kind of hard to get up onstage and lip-synch Barbra and then say, ’Drink up, everybody.’”

Lypsinka, who hopes to cross over from the stage into mainstream network television, disagrees. “Some people opt to do that [be political]. I don’t. I set out to entertain.”

The disagreements over style and form between Lypsinka, Lurleen, Vaginal Creme Davis, and legions of other drag queens—politics versus entertainment—are not new.

The Judy Garlands of the drag queen world became the unquestioned norm during the heady disco days of the 1970s and 1980s, when drag bars blossomed throughout the country. Although there were several drag troupes, such as the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence and the Cockettes in San Francisco, who maintained a high profile at parades and demonstrations, it was not until the late 1980s and the acceleration of the AIDS crisis that drag embraced a political message.

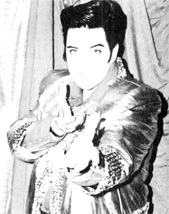

The late great Divine terrorizes and enthralls his 1978 audience at the Trocadero in San Francisco. (Dan Vicoletta)

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?

In 1974, Tommie Temple, a female impersonator, was fired from his job as show director and star of the Jewel Box Lounge for being gay. The Kansas City liquor ordinance said that a bar could not employ a homosexual.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Magnolia, a/k/a Tommy Keene, reigned over drag queens in West Alabama and Northeast Mississippi in the late 1980s and early 1990s, performing regularly at Michael’s, the gay bar in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, owned by and named after her stepfather. Her mother, Mary Ann, once joined Magnolia on stage for a lip-synched rendition of “Mama, He’s Crazy,” by the mother/daughter country-western duo Naomi and Winona Judd. Magnolia and fellow drag queens Princess DeShaye and Coco Chanel traveled and performed throughout the region, accompanied by their hair-stylist Grant LaTondress.

Clearly, today’s drag artists have a lot more on their minds than tight wigs. “[Political] drag is absolutely, unquestionably experiencing a comeback,” claims Martin Worman, aka Philthee Ritz, one of the original members of the Cockettes. “The Cockettes didn’t have a dogma. Now drag has an edge and a conscience because of AIDS.”

“The difference between old-line drag and new drag is that those performers took themselves seriously,” continues Lurleen. “That’s tedious in any form of self-expression. What we do reflects the mentality of our generation. We approach serious causes with humor and react to what’s going on in our culture and society.”

The setting for this rebirth can probably be traced to the Pyramid Club in Manhattan’s East Village, where acts like the band Now Explosion and performers such as Hapi Phace, Tabboo!, and the late Ethyl Eichelberger honed their considerable talents in front of an audience that included New York’s intellectual and social elite.

“Now drag is about trying new things,” explains New York drag figurehead Lady Bunny. “It isn’t limited to lip-synching. There is a new generation of queers whose icons aren’t Barbra, Judy, and Eartha.” Instead, blaxploitation films, 1970s sitcoms, glitter-rock bands, or parodies of other drags are now de rigueur inspirations.

“Drag adds an element of fun to politics so that it’s not all Maoist uniforms and being glum and gray,” says the platform-heeled Lurleen. “Hopefully it makes thinking about politics more palatable.”

Lypsinka, whose lightning-paced lip-synch revue I Could Go On Lip-Synching! has had tremendous financial success on both coasts, says that although he has performed at AIDS and gay-related fund-raisers, he sees himself as “not political at all.”

“It’s easier to digest Lypsinka’s kind of performance,” explains self-styled “blacktress” Vaginal Creme Davis. “It’s safer, and people aren’t challenged. But when people see an African American in this feminized role, they realize that there’s a whole spectrum of being out there and that the black experience or the queer experience is not just limited to one aspect.”

Of course, drag performance is not strictly the domain of men. San Francisco is also home to Leigh Crow, whose character. Elvis Herselvis, puts an ironic spin on Elvis impersonators, discussing the King’s drug problem and making copious references to “little girls in white cotton panties.”

Shelly Mars’s male characters have a somewhat harder edge. The New York performer’s best-known character is Martin, a leering, cigar-chomping man in a baggy suit who performs a striptease and fondles his dick. By the end of the performance, Martin transforms into a woman and the idea comes full circle.

Mars’s newest male character, Peter, is a person with AIDS is ho is slightly psychotic from medication and dementia. Modeled after people she met through ACT UP and friends who have died of the disease, Peter elicits very powerful reactions from her audience.

“It’s a scary thing to do,” says Mars. “You never know what kind of response you are going to get. Some people think that since I am portraying an insane character, I am making fun of him or saying all people with AIDS are this way. That narrow-mindedness comes from their own denial.”

Beyond the politics and the divisions it engenders, there is a common thread running through the drag community: the desire to get audiences thinking about their own sexuality.

“We challenge gender roles,” explains Glennda Orgasm of the New York public-access cable program The Brenda and Glennda Show. “And even though it’s a campy parody, it goes beyond that. A lot of gay men are bothered by their own femininity. Like ‘I’m gay, but I’m not feminine. I’m not a fag. I’m a man, even though I like to suck cock.’ Seeing a drag queen confronts all those fears. That’s why we do drag.”

Leigh Crow, performer and drag king extraordinaire, as her alter-ego, Elvis Herselvis. (Rink Foto)

“I hate that when they call me a transvestite. If I were a transvestite, I’d be sitting here with a little crocodile handbag

and a polkadot bow. Those are my work clothes. That’s how I make people laugh.”

“I hate that when they call me a transvestite. If I were a transvestite, I’d be sitting here with a little crocodile handbag

and a polkadot bow. Those are my work clothes. That’s how I make people laugh.”

DIVINE, DRAG LEGEND

“I understand the objection to drag from gays within the system who are working on gay and lesbian issues that way,” says Lurleen, “and yet I think that’s wrong. The issue is diversity and tolerance for people who are different and not just people who are different ‘our way.’ All oppressed people have something in common and need to work together.”

—JEFFREY HILBERT

Famed drag queen Miss Kitty, a/k/a Dan Jones (Dan Nicoletta)

“I speak for the individual. For anyone out there who’s ever had a dream and has had to listen to ‘Honey, you can’t do that.’ ‘We don’t allow blacks here.’ ‘We don’t allow fags here.’ ‘We don’t allow women in this bar.’ I am a giant ‘Fuck you’ to bigotry. Buddha, Krishna, Jesus, and now RuPaul. I’m about the politics of the soul. I transcend the gay community. I speak to everyone with pain in their heart.”

—RUPAUL, SUPERMODEL OF THE WORLD

“I mean, how political can a piece of clothing be?”

—GENDER, TAP-DANCING QUEER DRAG QUEEN

“The cross-dressers, to put it bluntly, we’re the ones who had the balls to say, Look—I’m gay!”

—JOSE SARRIA, FEMALE IMPERSONATOR AND LONG-TIME PERFORMER/ACTIVIST

“I kind of see drag queens as the suffragettes of the gay community.… I think the root of that problem really is various people saying, ‘I am ashamed of who I am and I don’t want anyone to remind me of what I am.’ ’Cause I can remember when I first came out of the closet, I hated camp men.”

—BOY GEORGE, POP QUEEN

“No matter what they say on Oprah or Donahue, I have never met a female impersonator who wasn’t gay. I met one guy who is married, but that’s a crock. I think those who are saying they are not and thinking that it will get them further are just wasting their time.”

—DRAG QUEEN POISON WATERS, 1992 QUEEN OF LA FEMME MAGNIFIQUE, THE WESTERN UNITED STATES PAGEANT TO FIND “THE MOST BEAUTIFUL FEMALE IMPERSONATOR”

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Wigstock, an annual drag celebration, attracts thousands of participants and spectators to Tompkins Square Park in Manhattan’s East Village every Labor Day. It was created in 1984 by New York—based Atlanta drag queen Lady Bunny in hopes of bringing “the drags of the New York club world into daylight.” The tenth anniversary festival in 1994 saw performances from the likes of Lypsinka and RuPaul.

For African American men, masculinity is a complicated issue: How do you define being a man in a society that doesn’t see you as one?

If you are homosexual as well, this issue is even more complex. All our cultural and social mores are based on heterosexual manhood. Furthermore, in the media—gay and straight—being gay is a white thing. I always believed, though, that I had society’s laws licked, that my being out challenged the notion that African Americans can’t be homosexual. It seemed so simple. But then I met Sydney.

Sydney is a six-foot-two, 225-pound nineteen-year-old with dimples for days, and Hershey’s chocolate skin. He is also a B-boy. That’s right—a ruffneck. There’s no such thing as a gay B-boy, you say? Sorry, but not all African American gay men walk the runway like RuPaul. Some of us appear on MTV and BET, rhymin’ and harmonizin’ up a storm. Of course, you can’t tell these home-boys are gay since they don’t “look” or “act” like it. Being banjie is the perfect disguise for an African American gay—or bisexual—male: Who would ever think that one of these hip-hop-lovin’, crazy crotch-grabbin’, droopy-jean-wearin’, forty-ounce-guzzlin’ brothers is a faggot? Yes, some wear a mask and wear it well.

But the mask slowly came off Sydney as he and I got to know each other, I was apprehensive at first. We have almost nothing in common (he worships Snoop Doggy Dogg; I love Rachelle Ferrell). He’s a bit too egotistical (he religiously wears a cap announcing I’M 2 SEXY 4 MYSELF). And he says the f word so much, you’d think it was his middle name. But a friend pushed me to give Sydney, who pursued me for two months after ringing up my groceries at the local supermarket, a chance. “You don’t know,” my friend argued. “He might surprise you.”

Well, he did. After a month Sydney and I became “a couple.” He’d drop by almost every day after school or work—sometimes with a rose or a bouquet of flowers—and I’d help him with his homework. We’d watch TV or play Scrabble or Trivial Pursuit (he’d usually win). Or we’d “max” in each other’s arms (which is a sight, since I’m six inches shorter and ninety pounds lighter) as he read me one of his poems (he wants to be a writer). Sometimes, though, he’d just cry on my shoulder—which he’d never do in front of his homies—because of the confusion he felt about his sexual orientation. He is a sweet, sensitive young man who, like most gay men, was brainwashed into believing he should be ashamed of who he is.

He was surprised when I told him his literary heroes—Langston Hughes and James Baldwin—were gay. He was shocked when I didn’t want to “get busy” with him on our first date. And he was even more bewildered when I refused to he “the woman” (as if his hand being attached to his penis 29–7 meant he was “the man”). Being around a gay man who respected himself and did not subscribe to a moronic machismo culture that brands women “bitches” and “hos” and homosexuals “punks” made him more comfortable talking about his sexuality. He let his guard down and let the real him come out.

As my relationship with Sydney blooms, I am filled with hope and love—but also anger. Our society’s warped ideas about masculinity have young men like him in limbo. Some commit suicide because they believe no one understands or cares; Sydney admitted he contemplated doing it once. Others adopt archaic sexual codes that force them to play roles. Sydney is beginning to see that acting “hard” doesn’t make him a real man, nor will it change who he is.

Through him I’ve learned that as long as there is heterosexism, it isn’t enough to open only my own closet door. I must make sure others know they can too, especially the next generation. If we don’t serve as role models for young lesbians and gays, who will? How can they value their true selves if they believe that wearing a mask will make their lives easier? As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., once said. “Silence is betrayal.” And what bigger crime is there but to betray yourself?

—JAMES EARL HARDY

Lesbians and gay men have taken great pains to convince everyone, including ourselves, that our movement is not just about sex. Of course it isn’t. We have a thriving movement for civil rights, a myriad of cultural experiences and discoveries, and day-to-day life that goes on outside of our bedrooms. But sometimes we forget that, while our movement is not only about sex, sex is an integral part of our lives, our loves, and our political struggles.

AIDS has changed the ways we relate to our bodies and sex. For many gay men during the eighties, AIDS made sex terrifying, a forbidden pleasure that could mean death. Since that time, most of us have adjusted to sex in the era of AIDS, accepting responsibility for protecting ourselves and others. Still, though, far too many of us are ignoring the warnings and having unsafe sex. And since the onslaught of the epidemic, an entire generation of gay men and lesbians have come to sexual maturity.

Lesbians, too, have experienced a revolution in sexual thought and deed. During the eighties, lesbians came out of the closet about leather sex, S/M, dildos, and pornography. In addition, while methods of HIV transmission via lesbian sex are still hotly debated, lesbians are discovering latex, cellophane wrap, and other ways of decreasing the risk of AIDS.

Sex has become so serious. But what we are learning now as a people is that serious does not have to mean bad, nor does it have to mean we can’t have fun. Sex is a crucial part of our sexuality. This section explores several different ways in which sex, far from equaling death, equals laughter, liberation, and life.

As a gay man living an openly gay life before Stonewall, the effects of the Riots in my life were immediate. The excitement of insurrection was palpable; my friends and myself, already connected to progressive leftist political groups, were elated: this was our revolution. I began going to Gay Liberation Front meetings in Manhattan two weeks later (and am still going to political meetings twenty-five years later). I had understood that feminist writings had some meaning for me, but now I had a real, vibrant context for specifically gay political theorizing—a way to think and analyze how gay men lived their lives.

But more than any of this, Stonewall meant sex. It is not as though gay men did not have sex before the Riots; they did, and much of the sex was good, nurturing, exciting. But after Stonewall sex was different. Not only was there less guilt and less anxiety, but the promise of Stonewall was, in a very real way, the promise of sex: free sex, better sex, lots of sex, sex at home and sex in the streets. As Tony Kushner writes in Angels in America: Perestroika, sex after Stonewall was the “Praxis, True Praxis. True Theory married to Actual Life.” This sexual energy fueled the movement. It filled us with fervor and desire—not only for one another, but to change the world.

The advent of AIDS changed all that. Suddenly sex had become something that enslaved rather than liberated, something that was not only dirty but, in the original meaning of the word, dreadful. Once we’d realized that AIDS could be spread by sexual transmission—a process that took several years—it was clear that we had to change some of our behaviors. But behavior was not the only thing that began changing. Homophobic social critics began labeling all gay male sex as dangerous. Early safe-sex guidelines preyed upon gay men’s uncertainties and proscribed all kinds of behaviors—especially the more socially unacceptable activities such as S/M—as life-threatening. Promiscuity—whether safe or not—was condemned as unhealthy and regressive; monogamy was now to become the norm. Some gay psychologists proclaimed that AIDS would shift gay men’s behaviors from an “adolescent” stage of sleeping around to the more “mature” stage of monogamous coupledom. It was perhaps inevitable that early attempts to promote responsible behavior dovetailed with the most homophobic, anti-sex attitudes in our culture, and in many ways “safe sex” came to mean less sex, fewer partners, and less sexual experimentation. The sexual promises of Stonewall seemed to have ended, betrayed by reality and disease, fear and loathing.

“One strain of 1970s gay liberationist rhetoric proclaimed that sex was inherently liberating; by a curiously naive calculus,

it seemed to follow that more sex was more liberating. In other words, I should consider myself more liberated if I’d had a thousand sex partners than if I’d only had

five hundred.”

“One strain of 1970s gay liberationist rhetoric proclaimed that sex was inherently liberating; by a curiously naive calculus,

it seemed to follow that more sex was more liberating. In other words, I should consider myself more liberated if I’d had a thousand sex partners than if I’d only had

five hundred.”

MICHAEL CALLEN, SINGER, SONGWRITER, AND AIDS ACTIVIST

But in recent years it has become clear that our more traditional ideas about safe-sex education have not been completely successful. Some have argued that they have, indeed, failed as we have seen gay male seroconversion rates in cities such as San Francisco once again rise. The political right has argued that this is because gay male sexuality is intrinsically disordered. Some AIDS educators have suggested that the epidemic has caused many gay men to have a death wish. Others have argued that it is simply human nature to act irresponsibly. I would like to posit another response.

The problem with our conceptualization of “safe sex” is—and has always been—that it did not value sex enough. Sexual desire has become something to fear and to contain. Sex with one person was better than sex with ten, sex at home was better than sex at the baths, sex with love was superior to sex for sex’s sake: Sex was being seen as a luxury, a bonus, to good health—not as a necessity for it. It’s no wonder that safe sex based upon these precepts would be a failure. It ignored the reality that sexuality is a powerful force in our lives, that desire itself can be nurturing, that sex—in any number of manifestations—is an affirmation of who we are as queers living in the world. Of course, we have to be responsible in our sexual behavior, but that is quite a different matter from restraining our sexual desire or curtailing our sexual lives because of fear or dread.

The promise of sex that Stonewall delivered in 1969 is still with us today and its message is as important—if not more important—than ever. If we are going to get through the AIDS crisis, if we are truly going to love and respect ourselves as gay men, if we are going to grow and thrive in this homophobic world we are going to have to learn—once again—how to love and embrace our sexuality in all of its forms, all of its desires, all of its manifestations. If we can begin doing this, the liberating promise of Stonewall will set us free again today.

—MICHAEL BRONSKI

The “second wave” of feminism brought with it a double-edged sword with respect to public attitudes about lesbian sexuality. On the one hand, feminists identified the sexual objectification of women as a weapon of sexism and worked to eradicate it. This fight took various forms, including attacking the pornography and advertising industries and criticizing the ways men are socialized to treat women as objects for their pleasure. Emergent lesbian culture during the 1970s and early 1980s rejected the traditional sex roles projected for women, and challenged the notion that sexual freedom was attainable for women in the decades following the so-called sexual revolution.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Safe Is Desire, released in 1993 by the Fatale line of erotic videos, was the first full-length safer-sex video for lesbians.

On the other hand, rejecting the ways women have been sexualized by the dominant culture did not automatically give women positive images of ourselves as sexual. For example, many of the fashions lesbians adopted kept us from appearing sexually available not only to men, but to each other as well. Carrying out the agenda of women’s liberation in our own sex lives was challenging.

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

Approximately 675 new gay porn releases came out in 1994, including both higher profile “major studio” releases as well as the products put out by the rapidly proliferating “fetish” and “specialty” mailorder companies. Since “hard core” was legalized in the early 1970s, an estimated 4,000 feature-length products have been put out.

Lesbian-feminists resisted being defined by the main-stream as primarily sexual beings. At the same time, lesbians were having sex and regarding those experiences as an integral part of lesbian identity. There was a tension among some lesbians between those who wanted more public representations of lesbian sexuality and those who argued that these representations perpetuated sexist oppression.

In response to the need for more explicit and radical forms of lesbian sexual expression, in the 1980s a “sex-positive” movement for lesbians emerged. In just a little over a decade, the United States and British lesbian communities have seen a burgeoning in the publication, production, and distribution of lesbian erotic materials, sexual performances by and for women, and stores or catalogues that sell “sex toys.”

The real dilemma of women’s sexuality and AIDS is fear, stigma, humiliation, and estrangement. The goal is to feel close,

sexy, and passionate—and turn on and dig yourself.”

The real dilemma of women’s sexuality and AIDS is fear, stigma, humiliation, and estrangement. The goal is to feel close,

sexy, and passionate—and turn on and dig yourself.”

LESBIAN SEXPERT SUSIE BRIGHT, IN SUSIE SEXPERT’S LESBIAN SEX WORLD

Nowhere was this emergence of the sex-positive movement more prominent than in San Francisco. It started with a big bang in 1984, when Blush Productions created venues for live erotic dancing for women at places like the now defunct Baybrick Inn. In women-only, safe spaces—a radical change from the male-owned clubs attended primarily by men—evenings were marked by a fevered, ecstatic, tangibly sexual energy and excitement that was surely a first. The dancers and the audience spanned a range of lesbian identities—butch, femme, and everything in between—in all manner of attire from lace to leather, front uniform to street clothes.

Today the sex-positive community has as many diverse components and variations as one can imagine. Sex-positive describes lesbians who are reclaiming sexuality as an aspect of creative, spiritual, political, and loving expression long denied to women globally. Publications range from mild erotica and depictions of nudity to erotic stories and poems and videotapes of women’s fantasies by and for women. Groups range from women’s workshops on “Creative Explorations of Intimacy With Your Long-Term Lover” to “Tantric Sexuality for Lesbians” to “Bondage 101” and “Making Safe Sex Fun.”

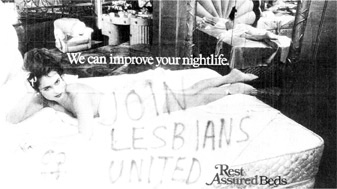

(Jill Posener)

DID YOU KNOW…

DID YOU KNOW…

In the industry, porn actors are usually referred to as either “models” or “talent.” They are normally paid by the sex scene (or “commercial scene”). They are never paid before completing a scene (commonly understood to require an oncamera ejaculation) and signing an elaborate model release providing iron-clad proof of legal age. The mean average pay today is about $600 per scene, with the range approximately $150–$1,400. There are a significant number of “top stars” who can work as often as they like and expect to always get at least $800. There are a small handful of “superstars” like Ryan Idol and Jeff Stryker who can demand greater one-time fees for a project. Idol was rumored to have landed $15,000 for his most recent flick.

—IDOL COUNTRY FOR HIS VIDEO

Sexually explicit publications created by and for lesbians began to appear on the market during the 1980s. A pioneer in this field was the lesbian-feminist S/M organization Samois, which produced the forty-five-page booklet What Color Is Your Handkerchief? A Lesbian S/M Sexuality Reader in 1979, followed by Coming to Power in 1981. On Our Backs was first published in 1984, about the same time as Outrageous Women and Bad Attitude came out of the East Coast. The year 1985 hailed the first lesbian erotic video, Private Pleasures and Shadows, followed in 1986 by Erotic in Nature, a representation of quiet and sensual lesbian-lovemaking in the summer trees. In 1987, lesbian-made and sexually explicit videos began to proliferate, including Rites of Passion, by Annie Sprinkle and Veronica Vera, and Burlezk Live, a lesbian striptease filmed at one of the Baybrick cabarets. Since the early 1980s, there has been a rapid increase in the number of magazines and books with all varieties of pornography and erotica. Even sex clubs—establishments open only to members and guests, safe sex only, alcohol and drugs not permitted—and the occasional sex party have been available to women in San Francisco off and on since 1978.

Thanks to the pioneering work of lesbians—Susie Bright, JoAnn Loulan, and Pat Califia—writing about forms and expressions of lesbian sexuality, lesbians in the 1990s are exposed to a wider range of possible sexual personae. The increased visual and written representations of lesbians as sexual beings and a cultural atmosphere that values sexual discussion and experience are some of the great fruits of the struggle for sexual freedom.

—MEGAN BOLER

Gay porn is the gay community’s perennial ugly duckling. All the same, it’s the most popular fowl in many gay households—more common than even the Thanksgiving turkey. Hardcore gay pornography is watched by a very large number of gay men. Even a lifelong conscientious objector to filmed carnality is likely to have at least a passing familiarity with some of the icons of the medium. In gay circles, exchanging frank viewpoints on Jeff Styker’s money-making member beats idle chitchat about the weather most any old day.

There are three basic positions gay men tend to take when talking about the sex-vid biz. And please—no snappy comebacks to that statement that begins “the first is hanging upside down in a full-body harness …” if you don’t mind! The first and perhaps the most common school of opining goes something like this: “Gay porn is just plain tacky and an embarrassment to our community. The production values in those videos are so shoddy! Surely as a group we can do better than this…” The second goes more like “Porn is a worthy pastime—but artistically expendable. It’s something to be kept by the VCR and watched now and then—but not if Murphy Brown is on.”

Zak Spears (left) and Tyler Scott, from the 1993 Hot House production, On the Mark. (Hot House Entertainment)

The third is along the lines of “Porn is its own art form, a valuable cultural tool, and a lot of fun.” In just the past couple of years, a small but growing number of perhaps more academically inclined individuals have begun to scrutinize porn video with less concern for its current artistic shortcomings and more attention devoted to its cultural potential. Because when you strip away the prudishness and societal stereotypes with which many of us have been preconditioned into approaching the subject of pornography, it can be argued that by the very nature of its explicitness, gay porn is well suited to portraying what it is that defines us as a group: who we choose to love and the way we go about engineering it. Mainstream Hollywood movies can (and occasionally even have) depicted our lives with vibrancy and insight. But Hollywood can never get the entire picture.

In the nineties, gay porn has infiltrated the American cultural mainstream more than ever. Whether it’s gay performers speaking out candidly on any number of daytime talk shows or the naked lusciousness that is porn boy Joey Stefano popping up in Madonna’s highly publicized Sex book, gay porn has obviously made its presence known across a broad range of folks who, a decade ago, would hardly have admitted to stopping in a bookstore and perusing the jacket notes on a copy of The Joy of Gay Sex.

DAVE KINNICK’S TOP TEN LIST OF GAY XXX VIDEOS

Best Friends, 1985, TCS Studio. Directed by Mark Reynolds.

The Bigger the Better, 1984, Firstplace Video. Directed by Matt Sterling.

Carnival in Rio, 1989, Sarava Video. Directed by Kristen Bjorn.

Cousins, 1983, Laguna-Pacific Ltd. Directed by William Higgins.

Getting Even, 1986, Videomo/French Art. Directed by J. D. Cadinot

Honorable Discharge, 1993, All Worlds Video. Directed by Jerry Douglas.

Pleasure Beach, 1984, HIS Video. Directed by Arthur J. Bresnan, Jr.

Sizing Up, 1984, Huge Video. Directed by Matt Sterling.

Two Handfuls, 1986, Bijou Video. Directed by John Travis.

The Young & the Hung, 1985, Laguna-Pacific Ltd. Directed by William Higgins.

An episode of the hit Canadian comedy series The Kids in the Hall summed up the lively public debate on the subject of gay smut when openly gay troop member Scot Thompson in a monologue featuring his flip and flouncy “queen” character, Buddy Cole, said, “On the topic of ‘Freedom of Choice’… The idea of persecuting gay porn is redundant. Gay life is porn. Nobody’s being exploited. What you see up on that screen are the community standards.”

—DAVE KINNICK

The gay and lesbian community is nothing if not complex. Millions of people with perhaps nothing more in common than an attraction to members of their own sex are lumped together as a community, wrongly assumed by many nongay people to have one set of shared values and goals. When it comes to sex, not everyone likes or wants the same thing. In the gay and lesbian world, there are a number of people, men and women, who find their identity and sexual fulfillment within the S/M and leather world.

Leather is about sex, costume, and erotic exploration. It is also about community, trust, and communication. The leather community has long taken care of its own; it was one of the first groups to insist that gay men and lesbians practice safe sex. Many early fund-raisers for AIDS causes were sponsored by the leather community, and among the responsibilities of the Mr. and Ms. International Leather titleholders each year is the promotion of AIDS and safe-sex awareness.

In the loose confederation of organizations, circles, causes, and individuals that make up the gay and lesbian community, few groups are more prone to misunderstanding by their fellow travelers than leatherfolk. The black-clad clan is as diverse as any other faction within the gay world, yet is narrowly viewed by many as a barely tolerable relic from homosexuality’s shadowing past.

Image-conscious critics see queers in black leather as a serious problem for a movement wanting to assimilate into society. The leather community’s confrontative public posture and its unapologetic advocacy of taboo erotic practices appear radical—even subversive—by mainstream standards. As a result, leatherfolk are often scapegoated by other gays as a reason for society’s dislike and distancing of homosexuals. Few such critics, however, would admit that the underlying reason for their prejudice toward the leather lifestyle is their own internalized homophobia and fear of difference. Leatherfolk, by their very nature, hold up a disquieting mirror.

What those outside the leather domain often fail to see is that through boldly exploring their bodies, many radical sensualists are nurturing spiritual growth within themselves. They’ve discovered that the S/M ritual helps to clear out the psychic basement, that deep inner place where troubling and fearful things are kept hidden. Long-held feelings of inferiority or low self-esteem, grief and loss, familial rejection and abandonment often come to the surface during S/M rituals. Rather than keep a tight lid on the psyche’s dark contents, these extreme sensual acts undo memories of the past and thus provide passage from the unconscious underworld to the aboveworld of self-realization and, ultimately, emotional healing.

Whether acknowledged or not, many urbanized gay men become attracted to radical sexuality because it offers some form of masculine initiation, the kind of rites of passage found in indigenous cultures around the world but usually lacking in their own. The process of masculine initiation traditionally begins with a rite of submission, followed by a period of containment, and then by a further rite of liberation—a psychological journey well known to leather practitioners.

Samois was a lesbian S/M support group that started is San Francisco in the late 1970s. For several years, the group produced a monthly newsletter, which included the advice column. “Ask Aunt Sadie.” The following is anonymous sample from this column, suggested to us for this book by Aunt Sadie herself.

Dear Aunt Sadie:

Here is “What S/M Means to Me” with gratuitous punishment, compliments of the Phantom Punster:

Sadism and Masochism

Sensual and Mutual (the basics)

Simply Magnificent

Sensory Memory

Sensual Magic

Sexual Magic

South of Market (San Francisco leather area)

Sex Maniac

Southern Methodist

Send Money

Sue Me

Service Manual

SM is the last word in feminiSM

Men, gay and straight, find their worth and define their manliness through trials of endurance. They must expose their limits, submit to fiery tests, in order to grow spiritually. It is the hero’s obligation to meet these rites of passage with faith intact, for they balance the eternal conflict between the claims of the ego and the soul. As any seasoned leatherman knows, one of the indispensable conditions of a successful S/M scene is the ability of the initiate to submit fully to the experience. A blackening must occur before any new light can dawn.

During the past decade, leatherfolk have been especially hard at work in strengthening the cultural ties that hind their community—in creating a new tribal identity. This collective effort has encompassed the preservation of the past (leathermen in major cities were among the first to fall from AIDS and also the first to rally against it), as well as a more profound articulation of radical sexuality’s spiritual implications—its potential for curing the wounds of the soul. For some leatherfolk, the definition of the term “S/M” has evolved in recent years from connoting sadomasochism, to implying sensuality and mutuality, to meaning “sex magic.” They see radical sexuality as an empowering, soul-making process—not the witless, pathological acting out of inner demons as some would claim.

Still, the idea that radical sexuality has spiritual value is a difficult one for most people to grasp. Even some leatherfolk reject the thought as well, confusing spirituality with religiosity and its condemning institutions. Few, however, would dismiss the transcendent moments of cathartic release they’ve experienced through intense erotic play. The enhanced physical, visual, and aural sensations of radical sex ritual allow for a transportation of self, or awareness of self, beyond normal even day references.

It is not unusual to find leatherfolk who are members of the clergy or the New Age movement, or who have explored psychoanalysis or various recovery programs—spiritually seeking individuals who are in some way seriously committed to personal and social change. By gaining the psychological insight made available to them through radical sexual practices, leatherfolk now stand among the gay community’s most consistently aware, socially responsible, and politically motivated members.

—MARK THOMPSON

Since the late 1970s, lesbians have been actively engaged in sharing their experiences and knowledge about the leather scene with other interested women. Support groups and safe-sex play groups have formed from San Francisco to New York. In the following excerpt from Coming to Power, “Juicy Lucy” provides us some insight into the lesbian S/M world.

Gabrielle Antolovich, an Australian native currently residing in San Jose, after being crowned International Ms. Leather in 1990 (Rick Gerharter)

Truth is an absolute essential. To build valid trust requires some ability to risk and some common sense. Since S/M is consensual there’s always some talking, before and after, so that you both (or all) know what’s going on. It’s a lot easier to trust a dyke when you’ve told her what you don’t want so you know she won’t accidentally cross your boundaries. It’s important to agree on a safe word, something you could say that would automatically stop the action.… I’ve found that I use the safe word much more often because my emotional boundaries are being crossed rather than because my physical boundaries are being crossed. Again, everyone’s experience is unique to her.…