Introduction

A Theory of Innovation, Flourishing, and Growth

Edmund Phelps

With the dawning of the 20th century, economics—from Wicksell in 1898 and Schumpeter in 1911 to Pigou and Ramsey in the 1920s and Samuelson and Solow in the 1940s to the 1980s—went beyond the static theory of prices and quantities, begun in the 19th century by Ricardo and generalized by Walras, to a theory of the economy’s development through time: the path of its capital stock and labor force, the path of the profit rate and the wage, and the growth of its productivity.1

That advance has been a central part of economics for decades. Besides providing better foundations for previously existing fields, it opened up new fields for analysis such as household saving and labor supply, business investment, exchange rates, and capital accumulation.2 Most striking, perhaps, was Schumpeter’s 1911 book going beyond the classical view of a nation’s development as simply its capital formation—investment and saving—to its innovation and entrepreneurship.

This “neoclassical” theory was nevertheless criticized as omitting features of a modern economy. In 1921, Frank Knight observed that firms making investment decisions typically faced “uncertainty” and J. M. Keynes wrote of “unknown” probabilities.3 In 1936, Keynes argued that, contrary to the neoclassical theory, markets cannot generally have the understanding needed to reach an equilibrium path, so the economy may drift into a slump or boom. In that event, he believed that monetary or fiscal policy could pull the economy back toward normal.4 Yet neoclassical theory remains the standard on growth—also wage and profit rates.

The most critical deficiency of this standard growth theory is its failure to recognize the core of modern life, of which Knightian uncertainty is just a part.5

Critical Shortcomings of the Standard Theory

In the standard economics, true economic growth—defined as growth of total factor productivity, a weighted average of labor productivity and capital productivity—comes out of a machinelike economy driven by “technical progress” (to use Solow’s term)6 that is solely or predominantly exogenous to the economy.7 This “progress” is the driving force: although some nations may maintain a higher level of productivity than some others, no nation can maintain a growth rate of productivity faster than the “rate of technical progress.”8 Technical advances with commercial applications prompt businesspeople with acumen and zeal to start new enterprises or reorganize existing ones in the expectation of profiting from the new step.

Schumpeter and others in the German Historical School thought that this “technical progress” arose from the discoveries made by the world’s “scientists and navigators,” which may have been true enough of Schumpeter’s Austria. Such discoveries were viewed as the prime mover while entrepreneurs undertook the commercial applications that a discovery made possible. This became the standard theory’s explanation of innovations—what Schumpeter called Neuren (new things). In his thinking, there were no people inside a nation’s economy who might be conceiving “new things” and thus potentially contributing to a nation’s innovation and growth—no indigenous innovation.9

But it is doubtful that these elements of the standard theory fit at all well the highly modern societies emerging in the past 200 years: largely the societies that developed in the 19th century—mainly in Britain and America, later Germany and France. Some points are suggested by the humanities, anthropology, and other social studies.

First, people in general—not just “scientists and navigators”—are capable of having original ideas, and many of these ideas (not only those of artistic people) might have commercial applications—just as scientific ideas might. Indeed, virtually every industry has had workers, managers, or others that hit upon new ideas at one time or another. Anthropologists have long believed that humankind has that faculty, and now there is evidence of that. Nicholas Conard and his team, exploring a South German cave once inhabited by some early Homo sapiens, found a functioning flute.10 If humankind has such remarkable talent, it seems possible that society, if willing, could institute an economy that permits and encourages the formation of new ideas, thus fueling innovation and economic growth.

Second, there is far more to a nation’s economy than growth. It is fair to say, painting with a broad brush, that the standard theory depicts people’s wants as entirely material: no more than their consumption (including collective goods) and leisure. Such a theory may have described life in a mercantile economy, like that in 18th-century England, but it omits the experiential dimension central to a modern economy—conceiving and trying out new ways and new things. In the standard theory, a person’s life is reduced to simply getting the best terms—finding where revenues are highest or the cost lowest.

Furthermore, the standard theory views the participant as atomistic, hence having no sense of impacting on the quantity or quality of any product supplied. Thus working life lacks any exercise of free will and hence any pursuit of the good life. The theory sees us as being robots from nine to five. That feeling is not the norm in a modern economy, however. There, the experience of acting on an idea of one’s own gives people a sense of agency—a feeling that they are making a difference in some small part, at any rate.

Because the standard theory does not recognize these dimensions, it can explain neither the intercountry differences in nations’ economic performance, material and nonmaterial, nor the rise and fall of this performance.

Regarding intercountry differences in material performance, the standard theory implies that productivity tends to be equalized, as capital and technologies flow to countries where they are scarcer. The data, though, show that, among G7 countries, productivity is far below what the theory would suggest in Britain and Germany while far above it in America.11 Conceivably, a country might keep ahead of the others if it had superior “entrepreneurship,” but Schumpeter made such an argument awkward for Schumpeterians with his insistence—in keeping with his theory—that the commercial opportunities opened up by discoveries were “obvious,” hence obvious to all.12

As for nonmaterial performance, the standard theory says nothing about any systematic intercountry differences either, since it does not see differences in the nature of countries’ economic experience. The data show that a measure of nonmaterial performance, mean job satisfaction, is high in Switzerland, Denmark, and Austria while low in Spain, Germany, and Italy.

Regarding intertemporal differences in economic performance, it is clear that the standard theory, having no predictive model of what it terms “technical progress,” does not explain them either. It is not capable of explaining such developments, material or nonmaterial. And there is a world of change to explain: historical evidence and recent studies show the rise of a secular exhilaration (the opposite of secular stagnation) in several nations, one after another, over the 19th century and a secular stagnation in one nation after another toward the end of the 20th. It is a serious failing of this prevailing theory that it offers no explanation whatsoever for either the exhilaration or the stagnation.13

How then to explain how a nation may gain—or lose—some of its economic performance, material and nonmaterial, relative to other nations and, for that matter, relative to its own past? Clearly, we will have to go inside the nations we are studying if we want to understand differences among them in what society wants to gain from its economy and in what it is able to gain. We will need to identify and gauge forces in society that help to explain how a nation might become able to innovate on its own.

A few theorists sought to show how a nation’s economy might play a wider role than Schumpeter conceived in the development of innovations—some going so far as to speak of endogenous growth in contrast to Schumpeter’s exogenous growth. In the 1960s, theorists (virtually all of us with ties to RAND) delved into the commercial application of scientific advances.14 Kenneth Arrow built a model of productivity gains through “learning by doing.”15 Richard Nelson and others wrote of “technological advances” through “industrial research” and the “diffusion” of new methods.16 In the 1980s, Paul Romer built a model in which successive variants of an original product line are introduced.17 In the 1990s, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt analyzed a model in which “research activities”—with probabilistic results—generate random sequences of quality-improving innovations.18 A 1990 model by Romer contains events labeled “new ideas.”19

We have to go beyond this—and in more than one way. We need to find forces that will produce sustained growth. Certainly, learning models do not if there are not new things to be learned. Industrial research teams seeking a commercial application of some scientific discovery appear to be creatures of Schumpeterian advances. (As Nelson said, industrial research would wind down if scientists closed shop.)20 Successive product lines do not constitute sustained growth either. “Research activities” and “new ideas” are a black box. The spark and the fuel are not described.

While, in modern economies and somewhat less-than-modern ones, organized corporate R&D—activities such as researching for new applications, learning by doing, and solving problems—may yield an occasional productivity gain or new product, no evidence has been presented to suggest that sustained innovation, growth, and job satisfaction are to some degree explained (in the statistical sense) by these activities. It is safe to say that these activities cannot have been the source of the productivity explosion of the past 200 years.

We also need to take into account the new ideas of ordinary people and the wellspring of those ideas. Even if some statistical correlations should be found, to view the organized research activities of technicians in companies and government offices as fundamental to innovation, thus job satisfaction and growth, does not get to the bottom of things: it is a blinkered view of what individuals, inside or outside companies, are capable of conceiving and doing—with or without advancing scientific knowledge—and what things they want to do for their satisfaction. Thus, the existing “endogenous growth theory” is inherently missing key dimensions in human possibilities: the same ones missing in the standard theory.

The thesis expounded in this introduction and to be tested in the body of this monograph takes a different view. Its fundamental premise is that people from all walks of life, not just scientists and lab technicians, possess inborn powers to conceive “new things,” whether or not scientists have opened up new possibilities. And a modern society allows and even encourages people to act on newly conceived things—to create them and try them—which stimulates people to conceive the new. The whole nation might be on fire with new ideas.

The implication is that, whatever Schumpeterian innovation may be occurring, in highly innovative nations, much of that innovating is indigenous: it springs from the powers of originality and creativity among large numbers of people working in the nation’s economy.

In this thinking, a nation may possess the dynamism—an appetite and capacity, a desire and capability—needed to create innovations and a willingness as a society to accept their introduction into the economy.21 Of course, such a nation may encounter obstacles—external ones such as wars or climate and internal ones such as regulation and bureaucracy. In general, though, the more of that dynamism a nation possesses, the more apt it is to attempt and succeed at innovating. Of course, current conditions, such as the general business outlook or political turmoil, may not warrant the attempt.

The next section points to major evidence of the sources and the rewards of this dynamism, drawing on histories of indigenous innovation in modern times—the early 19th century to the present age.22 These sources and rewards are tied up with the personal values that came to the fore in those times: the willingness to attempt innovation may be tied to developing conceptions of the “good life.” This theory has grown out of work beginning soon after the founding of the Center on Capitalism and Society in 2001 and culminating in my book Mass Flourishing, published in 2013. (Work on the present volume has led to a better understanding of many matters, but the basic thesis to be tested is unchanged.)

The Rise of Dynamism and the Impetus of Values

There were forerunners of Mass Flourishing, of course. Two scholars stand out for their accounts of the unprecedented economic performance that developed in large parts of the West over the 19th century.

In his first book, The Process of Economic Growth, the economic historian Walt Rostow, looking at centuries past, noticed that economic growth had always been episodic, and the rare outbreaks were typically reversed until, in the 19th century, there were—in his inspired term—“take-offs into sustained growth”: Britain and America around 1815, Germany and France around 1870.23 Countries busy copying the new methods and products passing the market test in a “lead economy”—the Netherlands and Italy, for example—saw their own growth rates pulled up. (The further they were outstripped by the leaders, the faster they grew.)24

In any nation where it took hold, this growth was immensely powerful. It transformed the nation from agricultural to industrial, from rural to urban, and from trading to producing. New cities sprouted up and new ways of life arose.

In a vivid portrait, The Birth of the Modern: World Society 1815–1830, the eminent historian Paul Johnson introduces us to many of the vast number of people whose originality and daring were characteristic features of the modern life that arose in Britain and to a lesser extent in America and continental Europe. Writing about hundreds of innovators—some businesspeople, some scientists, and some artists—he depicts the experimentalism, the learning from mistakes, the curiosity, and the courage to fail that personified the modern people. He also shows us that these people, though gifted for the most part, came mostly from ordinary, not privileged, backgrounds.25 Johnson was on to something quite important.

Mass Flourishing presents an explanation of this modern life—how it emerged and why it was valued.26 It points out the new outlook on life—the new attitudes—that permeated Britain and America: going one’s own way, seizing one’s opportunities, and, as Dickens conveyed, taking control of one’s life. The English spoke of “getting on,” meaning they were getting somewhere—perhaps getting ahead.27 Some of these attitudes have been found in contemporary documents by the historian Emma Griffin.28 My book argues that this new outlook on life spread through much of the West in the 19th century and is reflected by the Romantic movement in music and art. And it, more than anything else, brought about a transformation of the economy.

It was this new spirit that gave rise to an unprecedented dynamism. Businessmen might seize unnoticed or neglected opportunities to have better ways to produce existing products or have better-selling products to make—“adaptations,” in Hayek’s term.29 There were some adventurers in Renaissance Venice too, but that was nothing like the spread of entrepreneurial pursuits witnessed in the 19th century. Firms of a more entrepreneurial bent were springing up all over the economies of Britain and America. The agglomeration of such firms led to the emergence of more cities (but they were not a driver).30

Workers too brought this enterprising attitude to the workplace. The supply of labor—in the working class and middle class—shifted more and more from work that was routine or dull toward work that was challenging, hence engaging, in offices, yards, and shops. Employees might be keeping an eye out for better ways to do their job or organize their work. This new workplace was important. Marshall, observing in 19th-century England, thought so: “The business by which a person earns his livelihood generally fills his thoughts during by far the greater part of those hours in which his mind is at its best; during them his character is being formed by … his work … and by his relations to his associates in work.”31 Thus, both demand and supply brought people to the new kind of workplace. It was a subject of discussion for decades, from Tocqueville32 to the young Marx.33

But, far more important, the new outlook brought a spirit of imaginativeness to people in the economy. Some people might be dreaming up a new product, other people might be conceiving a new way to produce, and still others might be thinking up a new market for an existing product. Everyone was looking for a new way to do something, a new thing to do, or a new thing to use.

It was not a “trading economy” led by enterprising merchants and entrepreneurs that had arrived. It was an “innovation economy”—an economy built by a modern society. At its core was a “vast imaginarium”—a space for conceiving, creating, marketing, and perhaps adopting the new. Hume, decades ahead of his time, was its first philosopher: he saw the necessity of imagination for new knowledge, the role of the “passions” in human decisions, and the mistake of counting on past patterns to hold up in the future.34

The emergence of this phenomenon must have been breathtaking. While the adaptation achieved by “entrepreneurs” could pull an economy to its frontier, or “possibility locus,” innovation kept on pulling up the frontier itself, and people had no idea when it would come to rest—or if it would come to rest. The results were spectacular.

But what was it about this new kind of economy—this new way of work—that made it desired? And why was the necessary fuel present in some nations and not in others?

Fruits of the Dynamic Economies

The takeoffs gradually brought rising material rewards. Wages were pulled up by rising productivity. Profits gained kept on exceeding profits lost. More and better food and clothing led to improved health and longevity. In Britain, which kept records, wage rates, which had been up and down since 1500 and depressed from 1750 to 1800 (the years of the First Industrial Revolution), finally “took off”—ultimately growing at the same rate as output per worker. Moreover, workers found a growing number of ways in which to spend their time and money—from theater to sports to pubs. (While it is suggested that pollution and crime in British cities offset much of the wage gains there, a study estimates that, taking account of amenities as well as the disamenities, “city size, on net, is an amenity.”)35 Ultimately, there were invaluable public benefits as well. As revenues rose, governments could take measures to combat disease and boost public health.

Yet for increasing numbers of participants, the material reward—though historic—was not the extraordinary feature of this unprecedented period. Some rewards from the dynamic economy were unprecedented—spread over the breadth of the country from the grass roots on up: there was an explosion of choices, which brought with it a thirst for more choices. Different sorts of jobs kept opening up, different firms kept on entering, and different kinds of goods for use by households kept on turning up. People found this exciting, needless to say. Lincoln, back from his tour of the country in 1858, exclaimed that “young America has a great passion—a perfect rage—for the new.”36 What may explain that “passion” that Lincoln noticed?

The dynamic economy brought with it invaluable nonmaterial rewards as well. Even in economies that were not dynamic, there were the rewards of learning things, having interchanges of information with others, and simply keeping busy—all of which are nonmaterial in essence and arise from the experience of work. Those working in the dynamic economy, however, were in a different world. It was rich in experiences offering nonmaterial rewards that provided a sense of agency: people working in a modern economy—most of them at any rate—were taking responsibility, using their judgment, and exercising initiative. There was also the allure of setting out into the unknown. (We may never know whether Lincoln saw these experiential benefits.)

In the modern societies arising in the 19th century, most people evidently felt a gain from being able to participate in this kind of economy—the excess of benefits over the cost deriving from the inevitable crises and slumps. A great many Americans, for example, did not appear ready at any time to trade away careers offering the prospect of those extraordinary rewards, however uncertain they were thought to be, for a life of security.

Modern Values: The Roots of Dynamism

Much research has ensued on the effects of this unprecedented development—less on the causes. Why were people in some nations happy to have such an economy in which to pursue their careers—and this in spite of the uncertainty of success—while people in other nations were not? And why do we find today some nations less drawn to such an economy than they once were? In short, what was it in some nations that led to a society willing and able to provide an economy with the dynamism to innovate? We might think at first that the spectacular rewards offered by that economy explain its rise. But that would not answer the question of why such a miraculous economy arose over the 19th century in Britain, America, France, and Germany and hardly anywhere else.

The explanation hypothesized here is that a relatively innovative economy tended to be found in nations having (relatively) modern people. People are not the same. Even if all countries would have the same nonmaterial rewards had they acquired a modern economy, the people in some countries might have drawn more satisfaction from those rewards—and hence be more drawn to a modern economy—than the people in other countries: their appreciation of some or all of the nonmaterial rewards might have been more pronounced. It is possible that the relatively modern people of 19th-century Britain and America had outsize desires for some particular satisfactions offered by the modern economies. Several such satisfactions come to mind.

- These “moderns” may have been people who took huge satisfaction in achieving something through one’s own efforts—and may have taken further satisfaction if the achievement resulted in better terms or more recognition.37

- They may have been people who felt huge satisfaction in succeeding—an older term for which was prospering (from the Latin pro spere, meaning “as hoped,” “according to expectation”). Successes come in many forms: an office worker winning a promotion for his achievement, a craftswoman seeing her hard-earned mastery result in a better product, a merchant’s satisfaction at seeing “his ship come in.”38

- They may also have been people who took enormous delight in the sense of flourishing they got from life’s journey—the unfolding of their career, the thrill of voyaging into the unknown, the excitement of the challenges, the gratification of overcoming obstacles, and the fascination with the uncertainties.

- These moderns may also have taken deep satisfaction from making a difference—“acting on the world” and, with luck, “making a mark.”

- They may also have enjoyed competing alongside colleagues to build a business or to stave off rival firms.

Going deeper, we may form hypotheses about the values in society that underlie the desire for some or all of these satisfactions.

The influence of individualism on these desires cannot be overestimated. The modernist satisfactions are inherently individualistic. The satisfactions of achieving, succeeding, flourishing, and making a difference are only or mainly one’s own satisfactions. (They may extend to those closest to one.) Individualism was first celebrated around the early 16th century—notably by Pico della Mirandola, philosopher of the Renaissance, and Martin Luther, founder of the Reformation—and it spread widely well into the 19th century.

Another key influence is vitalism. The dynamic economy appealed to people looking for challenges and opportunities that made them feel alive. It is impossible not to think of innovators as generally full of energy and dedication. The restlessness of Don Quixote in Cervantes’s timeless 1605 novel epitomized the vitalism emerging at that time.

The value that might be termed self-expression is another influence attracting people to work in an economy of dynamism. In being allowed and perhaps inspired to imagine and create a new thing or a new way, a person can reveal a part of who he or she is.

Mass Flourishing argues that a modern society and the resulting dynamism of its economy bloomed in nations where the humanist values that could fuel the necessary desires and attitudes had reached a critical mass. Figure Intro.1 contains a table of these values and desires.

Testing the Thesis of Dynamism and Its Roots

Before proceeding to test statistical support for this break with the standard theory, it should be acknowledged that although what has been sketched so far is a new thesis outside the standard theory, it is not a theory in the academic sense, usually a mathematical model.39 And a formal theory may turn out to have some uses. Interested readers may enjoy the appendix.

This volume’s purpose is to test the thesis in Mass Flourishing. This has been a three-stage process.

First, there having been no existing time series on indigenous innovation, we have created an econometric model of the types of innovation in a multicountry world with which to estimate time series of indigenous innovation (in addition to exogenous innovation and imported innovation) in each of the countries under study. These estimated time series provide estimates of both intercountry differences in rates of indigenous innovation in the past and, for each country, intertemporal shifts in the rate of indigenous innovation.

Second, we have drawn on attitudinal data from household surveys of the countries under study to test whether intercountry differences in attitudes expressing the modern values of individualism, vitalism, and self-expression largely explain—better than intercountry differences in more familiar dimensions such as institutions do, at any rate—the intercountry differences in economic performance, as measured by a potpourri of variables ranging from the standard (such as fertility and labor force participation) to the modern (such as indigenous innovation and job satisfaction).

Last, this investigation can be seen as a test of the very existence of dynamism. And that is a radical venture, since the literature aiming to explain differences in economic performance does not admit into its framework the existence of dynamism. The prevailing explanation of differences across countries in economic performance is focused instead on the role of institutions—thus paying little or no attention to values.40

This is hugely important. Where there is great dynamism, there is also an abundance of its characteristic fruit: achieving, succeeding, prospering, and flourishing. And where it is lacking, there is a joyless society.

Values are subject to change, however. The Renaissance values—referred to here as the “modern values”—that finally attained a critical mass in the 19th century, though initially articulated in much earlier epochs, were not strong enough at first to overcome other values. We must look, then, for evidence that some of the values that fueled the historic dynamism in the West have weakened—and watch for evidence that some competing values have strengthened.

Some discussion may be worthwhile before the statistical investigations of these questions.

Losses of Dynamism? Losses of Modern Values?

Data collected by the Penn World Tables and, recently, by Banque de France show that total factor productivity growth, which had been fast by historical standards over the years 1950–1970 in America and extraordinarily fast in France and Italy, fell to very slow rates in all four countries over the years 1970–1990, then partially recovered to the earlier rates in America and Britain while slowing further in France and especially Italy. (Germany is a special case.)41 A longer history offers another perspective: among the large countries that were in the economic lead over much or all of the 20th century—Britain, America, Germany, and France—growth of total factor productivity was markedly slower over the span 1990–2013, and still slower in the span 1970–1990, than it had been in the interwar decades, 1919–1939, and the span 1950–1970, according to the Banque de France estimates.42

Figure Intro.1. Societal values and economic performance

Popular explanations of this development, in presuming that all or most innovation is Schumpeterian, attribute the slowdowns of total factor productivity to a drying up of commercially usable scientific discoveries—a fall in the exogenous “rate of technological progress” driving economic growth in the standard theory.43 Yet that inference looks questionable: if the slowdowns of total factor productivity—nearly all of which began around 1970, by which time all the countries had recovered from the war, so there were no slowdowns on this account—were the result of a decline of scientific discovery, and thus a slowing of Schumpeterian innovation, slowdowns of total factor productivity would have arrived more nearly at the same time and been more nearly of the same magnitude. But perhaps someone will someday show the presence of forces that prevented the slowdowns from being synchronous and equal. So, contentions that Schumpeterian innovation played a major role cannot be excluded on this account.

Our desire to understand these slowdowns motivates much of this volume. Not all of the statistical findings have direct implications for the slowdowns, of course, and nothing like a “general-equilibrium” time-series model of indigenous innovation is estimated. Yet we can draw from the pieces some plausible, perhaps persuasive, inferences. There are four layers of questions to probe.

If the nations of the West have been suffering from generally slower growth of total factor productivity in recent decades, are the slowdowns attributable to a structural slowing of innovation, not merely a run of adverse disturbances?

If the nations of the West are indeed in the grip of systematic slowdowns of innovation, are they results of indigenous innovation in some or all of the most innovative economies rather than Schumpeterian innovation?44

If there have been major losses of indigenous innovation, whether or not there has been some loss of Schumpeterian innovation as well, are these losses of indigenous innovation to a large extent a result of losses in dynamism—not merely a run of bad luck by plucky, ever-dynamic would-be innovators?

If there have been serious losses of dynamism, is there evidence of losses in the modern values—or gains in the opposing values—that Mass Flourishing argued were the fundamental determinants of the level of dynamism? (It will be an advance in understanding if, instead of attributing the slowdowns to a decline of dynamism by default, we can point to deadly sources of a decline of dynamism.)

A few preliminary inferences may be ventured in spite of the complexity of our thesis. It is plausible to think that the nations engaged in high levels of indigenous innovation on top of the rather equal levels of their Schumpeterian innovation, to which all countries had relatively easy access, would have high productivity growth and have reduced productivity growth when indigenous innovation is low.

It is paradoxical, then, that America, Britain, and France, normally the most highly innovative nations in the world, have seen large regions “ravaged by deindustrialization” since the 1970s, to use President Emmanuel Macron’s phrase: America’s Rust Belt stretching from Appalachia to the Midwest, Britain’s West Midlands, and France’s Lorraine region. In the old industries of these regions, there appears to have been deep losses of innovation—so deep that aggregate innovation slowed in spite of the astonishing innovation in the new, high-tech industries. But the structure of an advanced economy is apt to be complex. One could imagine that the fall of investment and employment in these regions was caused by a change in the structure of innovation rather than a drop of innovation.

To the extent that the thesis here—the good life through innovation and innovation through dynamism—finds empirical support, it may throw light on the intense dissatisfaction of many participants in the economies of the West. Certainly, the falloff of dynamism offers an explanation of the severe slowdown of wages. In the view of some commentators, the slowdown of wages in America was deeply disturbing to workers, for they had grown up believing that rising wages would eventually provide them with a standard of living significantly higher than that of their parents.

The thesis may also shed some light on symptoms of discontent with the workplace. Perhaps there has been a significant falloff of the nonmaterial rewards of work in those economies—rewards that may have been more gratifying than the material rewards were. It is significant that household survey data have shown over recent decades appreciable losses of reported job satisfaction in most, if not all, of the nations that were once big stars in the innovation firmament—and, roughly speaking, intercountry differences in job satisfaction explain some 90 percent of differences in “life satisfaction.”45

Lastly, research by Angus Deaton has found a range of pathologies running at uncommonly high levels in America: suicide, opioid addiction, depression, and obesity.46 It is plausible that these symptoms too—in the countries under study, at any rate—are the effect of losses of dynamism brought about by widespread weakening of the same values that fueled dynamism. The widely commented changes in the nature of jobs—the loss of a sense of agency, of the experience of succeeding at something, and of the sense of voyaging into the unknown—could drain much of the meaningfulness of many people’s work.

What might explain the significant losses of dynamism? Some observers have called attention to changes in the values expressed by society as early as the 1970s. The American sociologist Christopher Lasch wrote of a “narcissism” among young people in America that has made them self-indulgent.47 A White House aide, Patrick Caddell, wrote that one is “no longer identified by what one does, but by what one owns.”48 Margaret Thatcher, the prime minister of Britain in the 1980s, said that “life used to be about trying to do something.”49 In his famous “malaise speech,” President Jimmy Carter called for a “restoration of American values” and a “rebirth of the American spirit.”50 It is fair to say that Carter and succeeding leaders could not revive the “spirit” on which the economy’s dynamism depended since they lacked any theory of what that “spirit” depends on. Mass Flourishing laid out a thesis on the set of values underpinning the dynamism that has fueled indigenous innovation.

From the perspective of the theory here, it is natural to hypothesize that the losses in dynamism were caused—to a large extent, at any rate—by losses in the modern values that had sparked the dynamism at the outset. This hypothesis passes an obvious test: the countries that showed the greatest losses of indigenous innovation—even percentage losses—appear to be the nations in which innovation was once greatest. But looking at values and dynamism in just one cross section of countries does not provide an adequate test of the theory advanced here. Econometric tests must be performed before we can be confident that the theory sketched here—in this introduction—has an important place in our understanding of the rise and decline of indigenous innovation in the West.

If all these observations and explanations are true enough, they invite the inference that Western nations—the nations hit by the slowdown of their own indigenous innovation and the nations hit by losses of innovations to copy from the lead economies—are suffering from a deficiency of dynamism and the resulting innovation. Qualifications may be in order and complications may have developed. But no other explanation is apparent.

We come now to the value added of this volume. Of the ten chapters that follow, the first seven submit the foregoing body of speculative theory to statistical and econometric tests. (Mass Flourishing gave two short chapters to preliminary tests of its thesis, but the present volume is the first to devote a volume to a battery of tests.) Do the results tend strongly to confirm the presence of indigenous innovation, not solely Schumpeterian innovation? Do they tend to confirm the reality of dynamism—its power when it was at its peak and its power now that much of it has been lost? Do the results confirm the existence of modern values, not just traditional ones? And if so, are the nations most endowed with modern values or least possessing traditional ones found to have the most indigenous innovation?

In this volume, we also struggle with some of the big economic questions of our time. If we are in the grip of a structural slowdown, is a fall of indigenous innovation the cause? And if so, is it the result of policies and policy failures or more the result of a profound loss of dynamism internal to society?

Though these matters are crucial, we cannot end there.

Shifts in the Direction of Innovation: Labor Adding and Labor Multiplying

No sooner did we embark on the battery of tests presented here than we became aware that, besides whatever losses of dynamism may have occurred in some Western nations, there had been a change not only in the rate of innovation but also in the “direction” of innovation—to use a once-familiar term. No one will wonder why we must take up this new development. Many in the public have become alarmed over the redirection of innovation toward advances in artificial intelligence, specifically its effects on jobs and wages—much more alarmed than they were over the slowdown of aggregate innovation that took hold in 1970 and again from 2000 to 2012 up to the present time.

Even if no part of the public was alarmed over the matter, there would nevertheless have been more work to be done. Just as it was high time early in the 2010s to evaluate the standard theory of growth and venture beyond it to propose a new theory of indigenous innovation, it is now high time to evaluate the present understanding of the effects of advances in artificial intelligence, or AI, leading to more sophisticated robots and to develop a theory of what consequences unfold following the introduction of robots into parts of the economy.

A very simple model I sketched in the spring of 2016 suggests that the arrival of squads of robots causes a drop in employment and wage rates—also a drop in prices, for that matter—in the industry or sector that acquires the robots. But, I argued, those are only the immediate effects, not the final result. The reduction of costs brought by such a wave of robots is rather similar to the reduction of costs brought by a wave of foreign workers arriving in some industry of an otherwise closed economy: economics does not predict a permanent fall of wage rates and jobs. As the consequent drop in wage rates spreads throughout the economy, the capital stock can be expected to rise until a new steady state is reached in which jobs initially lost are regained and wage rates regain their former level. In addition, the initial boost in profit rates leads to additional investment until the ratio of capital to human plus robotic labor has regained its former level.

Yet we need to move beyond that simple model to richer ones.

The last three chapters address a kind of innovation that is different from what was the sole kind of innovation until recently. These chapters bring into the picture a kind of innovation that was traditionally called labor saving. It is ironic that these chapters in a volume challenging the standard theory hark back to issues that were raised in the essay “On Machinery” by Ricardo, which prefigured the standard theory, and addressed by Samuelson, whose brilliant work epitomized the standard theory.

These chapters explore the range of consequences that the introduction of robots can have. A crucial distinction is that between robots that, so to speak, add their labor to that of the workers and robots that potentiate the productivity of the workers—“labor-adding” and “labor-augmenting” robots.

In that framework, a single batch of labor-adding robots would have effects much like those just sketched: wages fall and then recover. However, in one such case wage rates show only a partial recovery.

Prospects are much improved when the robots are labor augmenting. The initial impact on wages is ambiguous. But it is unambiguous that the wage rates take a path of unbounded growth.

Our hope is that this introduction will draw readers into the research presented in the ten chapters that follow.

APPENDIX

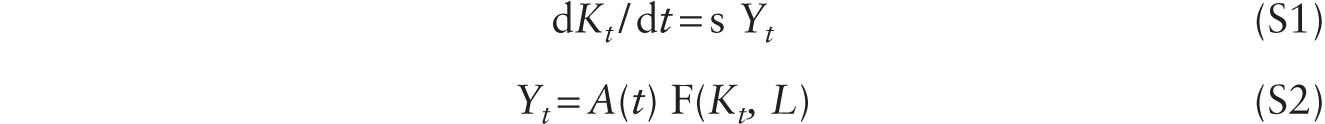

While a thesis may possess far more richness than a formal model can, models may reveal possible causal interactions or channels that might not otherwise be perceived. However, such models of indigenous innovation do appear to be possible. It took a long time for Schumpeter’s thesis to appear in formal models. The first growth model to be built on this thesis was first constructed by Solow:

Here, growth of aggregate output, Y, is driven by growth of total factor productivity, A(t), which is exogenous—generated by forces outside the economy.

Growth models can instead be built on the growth thesis tested in this book. We could replace Solow’s forcing function, A(t), with a state variable, B(Nt), measuring the force of cumulative indigenous innovation, Nt, brought by ideas born inside the economy.

A model in the spirit of the theory here describes an economy organized around consumer durables, intermediate and finished. In the labor force, homogenous and of size L, a number of participants are generally found engaged in creating new material, thus adding to the stock of intermediate capital, Kt. This is the number of participants, ξt, struck by ideas for new durables. (They prefer that sort of work to the others available.) The rest of the labor force is employed in producing from the intermediate assets a flow of new durables, thus constantly increasing the stock durables, D.51

This system is represented by the following pair of equations:

In equation (1), investment in D is an increasing function of both the current stock of undeveloped assets, K, and the portion of the labor force, L − ξ, engaged in its production—thus a decreasing function of the portion, ξ, creating new assets. In (2), investment in new undeveloped assets may be increasing in the existing stock of these assets and it is increasing in the part of the labor force producing additional capital.52

The latter model of growth puts people with new ideas into innovation but does not incorporate the possibly shifting values that lie behind the desires to imagine and create new products, just as the Solow model omits any shifting values governing efforts to make discoveries and achieve scientific advances.