Figure 0.1 Manchester City 2, Liverpool 1, December 26, 2013. Raheem Sterling is “miles” onside as the ball is passed to him; he was flagged offside.

“Yeeeeeeeeeeesss!” That’s me, Harry Collins, a seventy-year-old university professor, my thirty-eight-year-old son, who works for an economics think tank, and my thirty-five-year-old daughter, a senior civil servant. We’re high-fiving and rolling about on the floor. The final whistle has just gone and Liverpool has held on at Anfield, their home ground, to beat Manchester City and put the Premiership title in their own hands. It’s Sunday, April 13, 2013, and we’ve been watching the telly at a friend’s house in London, where my kids live. My wife has gone home to Cardiff on the train because she can’t stand the tension and she doesn’t want to see me have a heart attack. Insanity!

But Manchester City fans must be, as the football community says, “gutted.”1 Not only because they’ve lost, but because they’ve been cheated. There should have been three penalties in that game, and none of them were given. City’s Vincent Kompany put two hands around Liverpool’s Luis Suárez’s chest and pushed him to the ground in the penalty area; Liverpool’s Mamadou Sakho took a kick at the ball and missed it, hitting a City player instead; and Liverpool’s Martin Škrtel simply punched an incoming ball out of the penalty area with his fist even though he’s not the goalkeeper and is not allowed to touch it with his hands. If those three penalties had been given, the match would have been a draw and City would still have had the Premiership title in their hands.

Figure 0.1 Manchester City 2, Liverpool 1, December 26, 2013. Raheem Sterling is “miles” onside as the ball is passed to him; he was flagged offside.

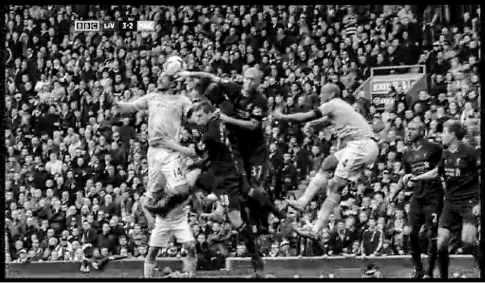

Figure 0.2 Martin Škrtel punches the ball out of the Liverpool penalty area. It was not spotted by the referee.

Are we saddened by the fact that we won by foul means? No—we’re whooping! First, because football fans like to win however it is done. But more importantly because this balances out what happened earlier in the season, when we played City at their stadium in Manchester. Liverpool’s Raheem Sterling was through on goal and would surely have scored but was flagged “offside” when he was two yards onside. City won, when it should have been a draw. What we saw on this occasion was the play of chance giving us justice. We should have had two more points at the Etihad, and City should have had two more points at Anfield. As they say, “It all balances out in the end.”

At least, that’s what most people say, but it isn’t true; and this book will prove it. What actually happens is that football fans are cheated, week after week. It is not only football fans, of course. On June 2, 2010, Armando Galarraga of the Detroit Tigers pitched a nearly perfect baseball game (it would have been only the twenty-first ever at this level) that was spoiled by an incorrect call, obvious to TV viewers and still obvious on the TV replays accessible on the Web; the runner was clearly out but the umpire called him safe (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armando_Galarraga%27s_near-perfect_game). The umpire even admitted, “I just cost that kid a perfect game.” But the baseball authorities learned their lesson, and since 2014 instant TV replays are available to baseball umpires. We will argue among many other things that they should be introduced in football.

Going back to football, we say fans are cheated because the lung-bursting effort and gut-wrenching emotion they imaginatively share with their teams is, as in the case of the Galarraga incident, made futile by clearly mistaken refereeing decisions. Ten million hearts are broken every week, and they do not need to be. “Cheated” is a strong word. The referees are not cheating; they are doing their best, and they often suffer along with the fans. Jim Joyce, the umpire who made the wrong call in the Galarraga incident described above, immediately felt terrible. In the book he wrote with Galarraga, he remarks that even though his mistake was not shown on a big screen, just a few moments later he felt humiliated as the fans were watching it on handheld devices and smaller monitors around the stadium (Galarraga and Joyce 2012, 212). A little after the game in conversation with reporters, he writes that he said “I feel like I took something away from that kid and I don’t know how to give it back.” And then he writes, “The rest is a bit of a blur because I break down at this point. Right then and there I start crying” (217). The players may cheat from time to time, but they too are not cheating the fans; they are trying to do their best for them.

Rather, it is the football authorities who are cheating the fans, because they could easily fix the problem but they won’t. In this book we’ll explain how they could easily fix it. We’ll ask why there has been such a fuss over the introduction of “goal-line technology,” used to determine whether a ball has completely crossed the goal line, when, in the 2011–12 and 2012–13 Premiership seasons, as far as we can see from the work presented in chapters 5 and 7, it could have corrected only five mistakes in total, and in the 2013–14 season, when it was brought into use, it resolved only six doubtful cases. That’s a maximum of eleven cases in three seasons. In those same three seasons we will be asking why, given our way of assessing these things, nothing was done about 161 incorrect penalty decisions, 86 incorrect offside decisions where goals were at stake, and 88 wrong decisions regarding red cards followed by sending offs—all crucial to the outcome of the games. Of course, you will have to decide for yourself if our way of assessing things is right, but even if it’s “miles out” it still makes goal-line technology pretty well irrelevant, while almost the entirety of what is going wrong can be fixed quite simply. Positions in the league table can change based on a point or even a single goal, so we’ll ask why, based on our calculations, individual clubs in the Premiership were cheated of up to a net nine points in the 2011–12 season or were unfairly awarded up to ten, cheated of up to seven points in 2012–13 and unfairly awarded up to six, and in the 2013–14 season were cheated of up to nine points and unfairly awarded up to eight. We’ll show that if these wrong decisions had been corrected, different clubs would have won the Premiership, different clubs would have filled the Champions League places, and different clubs would have found themselves in the relegation zone. So things didn’t “all balance out in the end.” And we’ll show how easy it would be to put all this right and let the players’ skill and effort decide the outcome of football matches rather than referees’ bad calls.

The results we’ve just outlined will be found chapters 6 and 7, but first, in chapters 1 and 2, we look at refereeing and umpiring in a new way and present a different way to think about the various technologies developed to aid umpires and referees. It is only by pulling all this together that we can justify our recommendation, which, to anticipate, is that TV replays should be regularly used by football referees for all the kinds of incidents described above, including goal-line disputes, while the way technologies are used in most other sports should be changed. We suggest that wherever possible, complicated technology should be avoided: “Use only what you need and nothing overly complicated or difficult to understand.” When complicated technologies are used, such as the Hawk-Eye “reconstructed track device” and its counterparts made by other firms, they should be used carefully to help match officials, not to replace them. “Reconstructed track devices,” by the way, is a bit of a mouthful, so from here on we’ll refer to them as “track estimators.” Track estimators use television cameras to try to reconstruct the track of the ball in relationship to the field of play and to try to predict its future path, impact point, and so forth. As we will see, even tracking a ball and estimating its impact point involves a certain amount of forward prediction from past data. We will argue that, currently, track estimators are used well in cricket but poorly in tennis, where they present a misleading impression of perfect accuracy.

We now set out the main arguments of the book that lead up to the reexamination of track estimators and to the three years of Premiership football. Among other things, we want to explain how this book differs from others that analyze decision making in sports. First, this book focuses on those who watch sports mostly on their home television screens which provide continual replays of incidents, and those who access TV replays on the big screens at some stadiums. This book is for television viewers, referees, and umpires, and it may be the first book on sports to put the needs of the TV viewer right up there with the other people watching, playing, officiating, and administrating. Second, the book blends a number of different ways of looking at things—we start, chapter 1, with some easy-to-understand philosophy to explain the nature of umpiring and refereeing. We then combine this with an understanding of the technologies used in sports to help match officials (chapter 2) and a simple explanation of the way measuring is done in science and engineering (chapters 3–5). It may seem complicated, but you need all these different ways of looking at things to understand how to solve the problem of better refereeing and better TV viewing. Without the philosophy it is too easy to be blinded by measurement; without the understanding of measurement it is too easy to be blinded by the technology; without the understanding of technology it is too easy to think that more technology is always better. What we conclude, and what drives the whole book forward, is that judging what is happening on a sports field is a matter not of ever-increasing accuracy but of reconciling what television viewers see and what match officials see—it is a matter of justice.

Resolving the problem does not require technology that is any fancier or more complex than the technology that caused the problem in the first place—regular broadcast-TV cameras. The drive toward higher and higher technology is motivated by conceiving of the problem of sports-officiating as exact accuracy in decision making. Thus, the high technologies claim to be able to resolve disputes about the position of a ball to within a millimeter; but such resolution is not needed if no human can resolve ball-positions in that way. Exact accuracy is, in any case, a shibboleth; this is obvious in games such as tennis, football, or rugby where the ball is filled with air. Such balls are “squashy,” and one cannot know the position of their outside envelope to within a millimeter because such accuracy does not exist. Nor are goalposts and the like erected using a micrometer. Again, in any game that uses lines as defining criteria, such as the goal line painted on a grass field in football, to say that one can define its edge to within a millimeter is ridiculous. What happens in the case of the high technologies such as track estimators is that the actual playing area and ball are replaced by a computer-generated virtual playing area and ball, but this is never made clear to the public; rather, the virtual is presented as actual. Nor is the public ever shown how likely it is that line calls produced by track estimators will be in error. In the body of the book we point out a number of such fallacies and misleading impressions.

What matters is not exactly where the edge of the ball is but where it appears to be to the human eye, just as has always been the case in sports. It is just that now the human eye can be enhanced, and is regularly enhanced, by TV replays. The use of this relatively low-level technology can solve the problems without misleading anyone. We show how it can be done without taking ultimate authority away from match officials and without slowing the game much or at all. The answer is that the umpire’s decision must stand unless TV can rapidly show that it was obviously wrong. If TV cannot rapidly show that a decision is wrong, then TV-watching fans cannot be seeing any obvious injustice.

But before we get to the details, we begin with a discussion of what justice means in sports.