Table 2.1 Classification of capture devices

Measurement technology in sports is a matter of capturing events. Match officials have to deal with fleeting moments; we want to grab the event as it passes and hold onto it for further examination so as to further enhance epistemological privilege. We can call sports measurement technologies “capture devices.” The moment of capture can also be time-stamped for comparison with the times of other captured events, such as in the case of the start and end of a race. We will now examine the technologies used in different sports and classify them in terms of five degrees of indirectness, as shown in table 2.1. We are going to use yet another new term and talk about “intermediation” instead of “indirectness,” because “indirectness” is a bit vague and all-inclusive. What we really want to get at is something more positive—the amount of “stuff” or number of processes that stand between the event itself and the view we get of it once it has been grabbed and held for further examination on a capture device. We want to look at how much is going on in the intermediate space between the event itself and the captured event that we get to look at in a more relaxed manner. This “how much is going on” is the “degree of intermediation.”

Table 2.1 Classification of capture devices

Level 1 technologies are the most direct: they have the lowest level of intermediation between the event itself and its frozen counterpart. Intermediation increases steadily as we go from Level 1 to Level 5. With more indirect technologies, the captured event is more and more distant from the original; more things have to happen in order for the event to be captured.

The cup on the golf green is a good example of a Level 1 capture device: there is almost no technological intermediation between the ball reaching the target and its fall into the cup where its position is held for all to see. Other Level 1 devices include the high-jump bar, the sand in the long-jump pit, the embedded javelin, the mark in the turf caused by the discus or shot, the surrounding wall in baseball, the chain between two poles in American football, and the pockets on snooker and pool tables. In other sports, the signal created by the capture device may not last as long, but the principle is the same. Thus, even though a basketball net does not trap the action, it does slow it down enough to capture it for all practical purposes; something similar applies to the goal net in association football and the winner’s tape in running events. In these cases, the technology enhances the epistemological privilege and ontological authority of match officials.

Some capture devices redefine the event to make it easier to trap. Consider cricket. We will return to cricket again and again as we work our way through the book, explaining it in greater and greater detail since it is a vital example of the use of sports technologies.1 We will start our explanation of cricket by looking at the differences and similarities between it and baseball.2

What we will refer to as “the basic transaction” in cricket is very similar to that in baseball, in that it involves someone projecting a ball and someone trying to hit it with a bat. In cricket, the person projecting the ball is called the “bowler” rather than the “pitcher,” and what the bowler tries to do is get the batsman or batswoman out. The batsman or batswoman is the equivalent of the batter in baseball. Because “batsman or batswoman” is clumsy, we will adopt the baseball convention and refer from now on to the “batter” even when it is cricket and not baseball we are discussing. Cricket is, however, a purists’ game, and we apologize to the purists for our abuse of terminology.

One way of getting the batter out in cricket is for the bowler to hit the “wicket” with the ball—there is no equivalent in baseball. The wicket (figure 2.1) comprises three vertical stumps—lengths of wood with a circular cross-section about an inch-and-a-half in diameter and twenty-eight inches tall, driven into the turf side by side so as to make a target nine inches wide. Thus the batter tries to defend the stumps, known collectively as the wicket. On some occasions it will be difficult to tell whether the ball struck the wicket with a grazing or gentle blow or missed by an imperceptible margin. To settle this kind of issue, two small sticks called “bails” sit in shallow grooves on top of the three stumps; the notion of striking the wicket is redefined as “breaking the wicket,” which means one or both of the bails must fall to the ground. Thus the falling of the bails traps the event—either the bails are both still balanced or at least one of them is on the ground—while redefining the event as a matter of dislodging the bails.3

But life is always complicated. Even with the use of the simplest Level 1 technology, things can go wrong. The bails may be affected by a gust of wind just as the ball passes, dislodging them even though the ball just missed the wicket. The golf ball sometimes teeters on the edge of the cup, and the player is not allowed to wait too long for it to fall but must walk up to it and tap it in without delaying overlong; it is the job of match officials to interpret what is to count as an “acceptable” delay. In football, the net does not always bulge when a goal is scored, as the ball can cross the line and bounce back out without touching it.4 It is also true that a high-jump bar can bounce around and fall off some time after the athlete has landed, and we need ways to judge what to do. In other words—and this is an important point to which we will return repeatedly in this chapter—there are cases where even the simplest technologies have to give way to, or be supplemented by, human judgment. Traditionally, in these cases, match officials have called on their ontological authority to determine the outcome.

Now we come to capture devices that involve a little more intermediation. The photo finish in horse racing is an example of a Level 2 technology: the positions of the horses at different times are presented in a single image captured by a special camera looking along the finish line. After some developments to the technology—going from a horizontal shutter to a vertical strip opening, from a still frame to a panning device and illuminating the finishing tape on dull days—the photo finish seems to have been readily accepted. The photograph is indirect because the horses are separated from the film on which their image is captured by the passage of light—unlike the golf ball, they do not fall into a pit when they reach their goal. Nevertheless, the technology is well understood and widely trusted. For example, no one worries that light takes a little longer to travel from the far horse than the near horse so the far horse might be around 1/10,000 of a millimeter, give or take or zero, further ahead than the photo finish shows. Compare this with the start of sprint races: the delay in transmission of the sound of the sprint-race starting pistol could disadvantage the far runner by hundredths of a second—and sprints are nowadays timed to hundredths or even thousandths—so in important races, each lane has its own loudspeaker with the signal transmitted across the track at the speed of light (electricity).

Crucially, however, the image produced for the photo finish still has to be examined and interpreted by a match official in order to determine who has won. In many cases, this is relatively straightforward—as it should be—but there are cases where the judgment and interpretation of match officials is crucial in explaining and justifying the decision. For example, in the 2014 Winter Olympics at Sochi, a close photo finish in which three skiers appeared to cross the line simultaneously was eventually awarded to Russia’s Egor Korotkov because he threw his arms in front of him and crossed the line head first rather than feet first.5

Turning to the spectators, from their point of view, capture devices help them share in the decision. They can see the golf ball topple, the bails fall, and the net bulge. The photo-finish image is a public document that explains why the match officials classified the result one way rather than another. The important point here is that the technology is trusted to gather the necessary data in a sufficiently accurate and reliable manner.

Matters become more complicated when several different pieces of information have to be integrated. Returning to cricket, consider the “run out.” This is akin to the decision in baseball as to whether a runner has made his or her base before being tagged. (See figure 2.2 for a diagram of the field of play in cricket.)

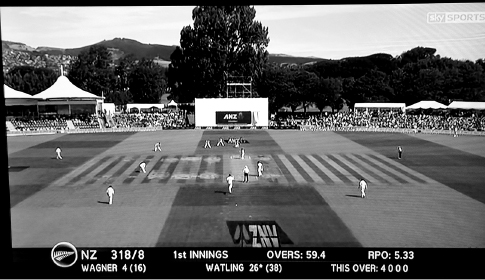

Figure 2.2 A cricket field with a very attacking field—all fielders are very close in. The field is set for a right-handed batter. For a left-handed batter, the offside and leg side (see chapter 3) and the fielding positions would be a mirror image. The boundaries are around eighty yards away; normally the field would be more spread with quite a few patrolling the boundaries and with a defensive field there would be fewer slips and no short leg or silly mid-on. The creases are shown with the gray box being the virtual space between the wickets. See figure 2.3 (and the figures in the “Bonus Extra” chapter) to see how this looks in real life, or search YouTube for more examples.

Figure 2.3 The field of play in cricket (Australia vs. New Zealand, February 2015).

A crucial difference, however, is that in cricket the batter does not score by running around bases on a diamond but by running directly toward the place from which the bowler projected the ball. Another set of stumps have been driven into the ground at that point, twenty-two yards away. The batter must reach that ground before that wicket is broken by the ball to score one run (runners are not tagged in cricket; rather, to get the batter out, someone must break the wicket with the ball before the runner makes his or her ground). If the batter has time to return and regain his or her ground at the end from which he or she started before that wicket is broken with the ball, then he or she scores two runs. If he or she can turn again and reach the far end once more, he or she scores three runs. On rare occasions he or she might return yet again to score four runs. A further complication in cricket is that two batters are on the field at once, one facing the bowler and one relaxing at the bowler’s end, awaiting his or her turn while the bowler bowls (unlike baseball, double plays are not allowed). To complete a run, both batters must make their ground at the opposite end from where they started before the corresponding wicket is broken; a strong hit will see both runners running backward and forward, passing each other in the middle of the “pitch”—the strip of ground that separates the wickets. If an odd number of runs is scored, the other batter will usually take over the batting, because the batters will now be at opposite ends. But bowlers change over every six balls bowled with the new bowler coming in from the other end, and the positions of the fielders switches around with him or her—six balls is known as an “over”—so it won’t always be the case that a new batter faces the bowler if an odd number of runs is scored; if the runs were scored at the end of an over, then the old batter will be at the facing end. In yet a further complication, the batters do not have to quite reach the far wicket to complete a run, but rather need to reach a line drawn across the pitch four feet in front of the wicket known as “the crease.” To avoid being “run out,” the batter—some part of the batter-plus-bat—must touch the turf beyond this line prior to, or simultaneous with, the wicket being broken. The wicket can be broken by the ball or by a player’s hand, so long as the ball is held in that hand. It doesn’t happen very often compared to the other ways of being out, but the run out does happen once or twice during a game.

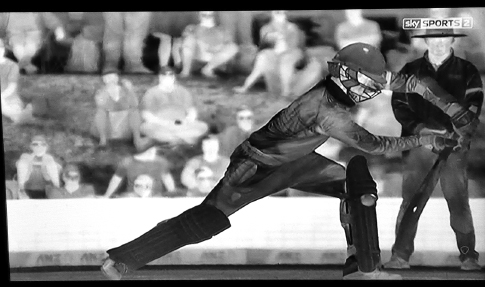

The “stumping” method of being out is closely related to the run out. Behind the batter stands or squats the wicketkeeper, roughly in the same position as the catcher in baseball though sometimes much farther back. The wicketkeeper’s job is to the catch the ball if the batter fails to hit it and it misses the wicket. Sometimes an ambitious batter will “leave the crease” and take a few quick steps forward when the bowler bowls so as to be in a good position to hit the ball really hard. But if the batter misses the ball, the wicketkeeper can grab it and break the wicket, catching the batter out of his or her ground. It is just like the run out except that the batter wasn’t trying to get a run, just get in position to strike the ball really well. What often happens in these circumstances is that the batter misses the ball, then turns and makes a desperate dive with bat outstretched to try to regain the crease before the wicket is broken; it is then up to the umpire to decide whether the wicketkeeper or the diving batter has been successful. Full-length diving with an outstretched bat is also often associated with attempts to avoid a run out, but in these cases the batter is running at full speed before the dive so it is even more spectacular and bruising.

The point to note is that in the cases of run outs or stumpings, it is not only a question of judging the exact moment when the wicket is broken—itself a much more difficult thing to judge than whether it has been broken at all—but also whether it was fairly broken (e.g., it would not be fairly broken if the wicketkeeper or fielder broke the wicket while the ball was spilling out of his or her hands) and the exact moment a third event took place four feet away—the batter’s grounded-crossing of the crease. In most cricket matches, there is no way to capture the exact moment the wicket was broken, the fairness of the wicket-breaking, or the split second at which the grounded-crossing of the line occurred. Instead, the ontological authority of match officials rests solely on their epistemological privilege: using their own perceptual abilities—somatic tacit knowledge—and viewpoint on the pitch, they must decide and categorize in real time and without the benefit of any technological support; of course, they have good epistemological privilege.

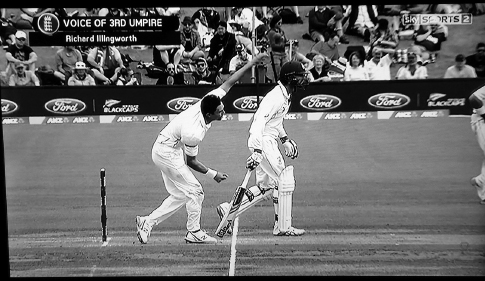

In televised games, however, technology can be used to assist the umpire: TV replays can provide a Level 3 capture device. It is a little more indirect than a photo finish because of the electronics in a TV camera, and a little more fallible than the photo finish because the technology was not designed for the sole purpose of assisting the umpires. As a result, the position of the cameras is less than optimal, the frame rate is slower than would be preferred for a purpose-built device, and more manipulation of the images—for example, zooming in and out, replaying in slow motion—is needed to provide the necessary information. In a typical stumping or run-out decision, a dedicated match official, known as the “third umpire,” has access to the various broadcast camera feeds; by zooming in, or selecting different views, he or she reaches a judgment about whether the batter should be “given out.” This decision is then relayed to the on-field umpire and to the spectators. As with the photo finish, the TV footage used to reach the decision can be made available to spectators, and, again like the photo finish, the technologies involved are pretty well understood and widely trusted. Needless to say, on some occasions the TV replays do not provide a clear image; but, when this happens, spectators can see the problem too and cannot reasonably feel that a great injustice has been done when the off-field umpire finally uses his or her best judgment to make the call.

Another kind of difficult judgment that cricket umpires often have to make is whether or not the ball just brushed the edge of the bat before being caught by the wicketkeeper. In cricket this counts as “a catch” and the batter is out. The difference between “caught behind” (by the wicketkeeper) and a foul tip in baseball, where the catcher catches a ball that has touched the bat, is nicely set out on Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foul_tip).

The foul tip is roughly equivalent to caught behind in cricket except that whereas in cricket a batter caught behind is immediately out, a caught foul tip only counts as one strike so a batter would only be out from a foul tip if he was already on two strikes. Caught foul tips are rarer than caught behind in cricket for two main reasons. The round shape of a baseball bat means that slight deflections are more likely to deviate significantly, making it more difficult to catch; by contrast, a cricket bat has flattish edges. Also, a baseball catcher must take position immediately behind the batter, meaning that he has less time to react to a tip. There are no restrictions on where the cricket wicketkeeper stands, and he or she can often be as much as fifteen yards behind the batter, giving him or her more time to react to edges, especially when facing fast bowlers. Furthermore, it is not unusual for there to be extra fielders beside the wicketkeeper, called “slips” (see figure 2.2), who can catch bigger deflections. Extra fielders behind home plate are not permitted in baseball and would probably be of little use anyway.

It should be borne in mind that in cricket the area of the field of play behind the batter is every bit as much part of the playing area as the area in front or to the side: there is no “foul area.” As a result, one elegant shot that a skillful batter can play is the “late cut,” where the ball is deflected very slightly as it speeds past the batter—the less deflection, the harder the shot—so the motion imparted by the bowler carries it past the wicketkeeper into the part of the field behind the batter, thus allowing runs to be scored. The “leg glance” achieves the same effect but on the other side. Other batting strokes, the meaning of which we discuss in the “Bonus Extra” chapter toward the end of the book, include the cut, the square cut, the hook, the straight drive, the on-drive, the lofted drive, the sweep, the slog-sweep, the slog to cow corner, and, introduced more recently in response to the emergence of the limited-overs game (see again the “Bonus Extra” chapter), the reverse sweep and the ramp shot (but don’t worry about them).

But perhaps the ball that seemed to touch the edge of the bat with hardly any deflection, leading to an apparent caught behind, actually just missed the edge! The visible effects of such slight contact are very hard to see in real time and are often below the resolution and frame rate of the TV cameras. As a result, television replays can provide little extra information and rarely provide a sound basis for overturning the on-field umpire’s decision. Level 4 devices (see below) have been introduced to try to resolve this kind of problem, but, in their absence, spectators can at least see that, whatever the umpire’s decision, he or she has made no glaring error—given the resources available, the umpire could not have done any better. There is no obvious injustice, and ontological authority resolves the issue.

More seriously, in some circumstances TV replays are known to be misleading. One is the decision over whether a ball has been fairly caught. As in baseball, a player is out in cricket if the ball is struck and then caught by a fielder before it bounces. In cricket, by the way, the fielders, other than the wicketkeeper, do not wear any kind of gloves—it is all bare hands. With a low fast catch it is sometimes not clear if the ball flew straight into the fielder’s hands or hit the turf just in front of the hands before being caught. All commentators agree that the foreshortening effect of TV replays means they often appear to show that the ball did bounce, and many commentators point out that this kind of TV replay almost always gives the benefit of the doubt to the batter, who is then given “not out.”

Level 4 devices differ from Level 3 devices in that the intermediating technologies do more than re-present events that were, in principle, available to an on-field match official with perfect vision and discrimination. Instead, Level 4 technologies generate new data that would enhance even the most perfect human’s perceptual abilities by allowing him or her to see things from new angles and via nonvisible wavelengths and transpose sound into a visible waveform. Level 4 devices can resolve the “caught behind” problem in cricket.

In cricket, Hot Spot is a Level 4 device that uses infrared cameras to detect the heat produced by contact between bat and ball and indicates whether the ball has touched the bat in case of a disputed catch. Impact between bat and ball will show up as a bright spot on the edge of the bat in the black-and-white infrared image captured by a special TV camera. Here the intervening medium is infrared light, which makes this technology more complicated and less well understood than standard photography. Higher-level capture devices, because they are complicated and involve novel applications of new technologies, tend to fail in unexpected ways. Thus, only after some years was it realized that Hot Spot may not work well if the weather is very hot and that it may fail to detect a slight contact if the edge of the bat is greasy.

As time has gone on, Hot Spot is often complemented by another Level 4 technology—“Snickometer” or “Snicko,” or some other propriety version such as “UltraEdge”—that generates an oscilloscope-type image of the sounds made at the crucial moment. This chart is synchronized with and superimposed over TV film to show whether the sounds heard were caused by contact between ball and bat or some other object. Because the shape of the trace will be different for different kinds of contact, Snicko seems to enable umpires to distinguish between the ball hitting the bat—a sharp, spiky trace—and some other kind of contact, such as the ball striking the batter’s clothing or pads (see below), the bat striking the ground, and so on, which will produce a more “woolly” trace. When used together with TV replays, Hot Spot and Snicko (see figures 2.5 and 2.6) seem to provide an acceptably reliable combination of Level 3 and Level 4 capture devices and to perform a useful function in correcting errors and reinforcing the epistemological privilege and ontological authority of match officials with the process viewed and understood by the TV audience.

Figure 2.5 Hot Spot.

Figure 2.6 Snicko.

Pundits and commentators also use a combination of capture devices to reveal the accuracy of offside decisions in football. Here the simultaneity of two events has to be judged, but the events are not colocated and may be as far apart as the length of the football field. The two events are the moment the ball leaves the foot of the player passing it forward and the position of the receiving player in relationship to other players at that moment. At that moment, no part of the receiving player’s body must be farther forward than the last opposition player (goalkeeper aside). The optimum position from which to judge the relative position of the receiving player is level with that player, while the optimum position from which to judge the moment the ball was kicked is level with the kicker. The duty of making this judgment is given to a specialist “assistant referee” (once called a “linesman”) who is advised to patrol the sideline, keeping up with the front players. TV replays that capture the whole field can usually reveal the moment when the ball was kicked, but they are less good at indicating the relative position of the front player, because the view of the TV camera will almost always be at an angle rather than along the line of the front players.

Introducing more intermediation moves us nearer to a solution to the offside problem. Computer graphics techniques can be used to capture the crucial TV frame as a virtual image, rotate the scene electronically, and draw a virtual line across the field that is level with the front players at the moment the ball was kicked; the TV viewer seems to be able to look along this line. BBC’s Match of the Day program uses such transpositions, but they do not, as yet, influence the decisions of match officials. There are no published statistics about the accuracy of such methods and the BBC would not respond to our requests to discuss this with them, so we cannot be sure how accurate they are—but we have no reason to doubt their accuracy. One might argue that the accuracy of this device does not matter, as it is not used by referees. But it does appear to reduce the epistemological privilege of referees and erode the grounds of their ontological authority, so it is important nevertheless, and we should know how well they work. We will assume they work accurately, but we do not know.

Now we move to highest level of intermediation, in which technologies—track estimators—are used not just to record or re-present data but to generate simulations of the on-field events. Hawk-Eye was the first and probably the most well-known of these technologies. Using specialist cameras, track estimators gather data that indicate the position of the ball in play and try to reconstruct its track in computer-generated graphical form within a virtual version of the playing area complete with boundary and other play-defining lines. The resulting animated computer graphic is taken to show the path of the real ball and, crucially, exactly where it bounced, or struck some other feature of importance such as a batter’s leg. We will discuss the use of track estimators at length in chapters 3 and 4. With the appropriate use of computer-generated images, the reconstruction offered by a track estimator can appear to be the equivalent of a television replay, but a much greater amount of inference, calculation, and computation stands between the events and reconstruction than stands between TV cameras and broadcast video. Also, the position of the reconstructed ball within the simulation is always judged in relation to the virtual model of the playing area and not against the actual playing surface, while the bounce footprint of the ball is a mathematical model, not a recording of actuality.

We will draw on this classification of technological aids in terms of levels of intermediation throughout the book. What we will try to establish is that, other thing being equal, less intermediation is better than more intermediation because the higher up the scale of complexity you go, the more expensive things are, the more things there are to go wrong, the more the public can misunderstand what is going on, and the less the technically assisted game is like the game the rest of us play. We will argue that more complex solutions arise out of an obsession with accuracy rather than justice; to resurrect justice in sports, we need to return as much ontological authority to the match official as possible.