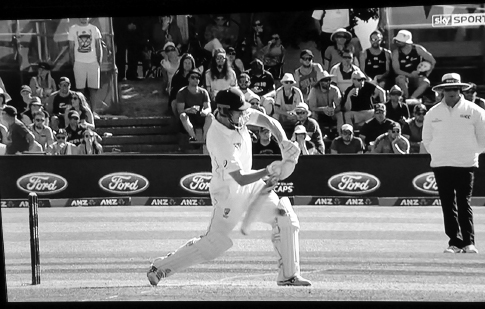

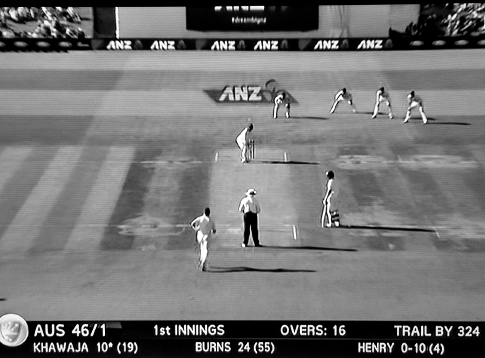

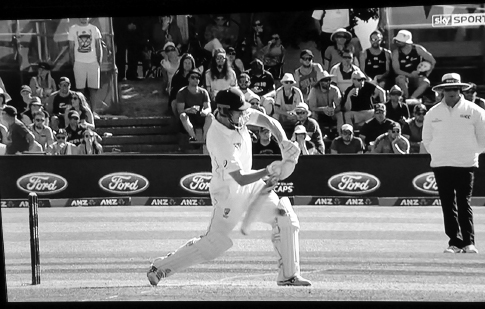

Figure A.6 A run out in a limited-overs game with colored uniforms.

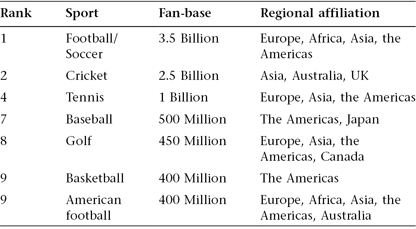

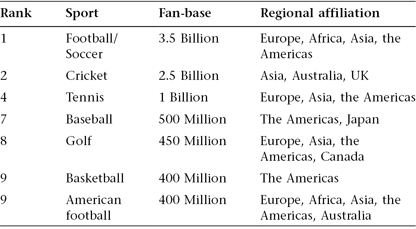

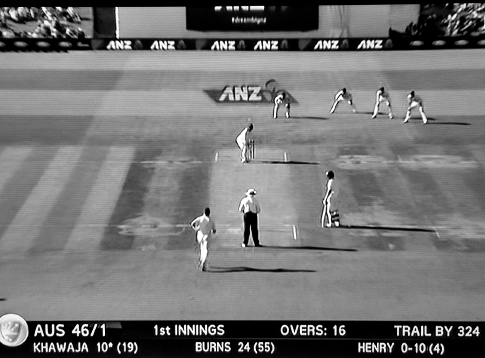

Table A.1 The popularity of some top sports according to website usage

Readers of this book from countries where they are unfamiliar with cricket have already had to learn a lot about the game. Having had to put so much effort already, they might want to learn a little more. After all, one website (http://www.topendsports.com/world/lists/popular-sport/fans.htm), using visits to sports websites as a metric, finds that cricket is the second most popular sport in the world; it may be coming your way! The website’s ranking of popularity of some top sports with their regional fan bases is shown in table A.1.

This means that learning a bit about cricket might not be a complete waste of time even if you don’t live in a cricket-playing-country, and it is, in any case, increasingly possible that you may get a chance to watch it on one of your native TV channels.

Let us start with the bat, the starting position of which in the batter’s hands is usually vertical, with the far end—the toe end—tapping the ground. It differs from the baseball bat, having a flat face a little more than four inches wide and twenty-two inches long, held by a round handle at the top about a foot long and an inch and a bit in diameter. It has thick edges about half an inch deep and bulges out at the rear to a depth of about two inches so as to create a sweet spot eight or nine inches up from the toe end.

The ball reveals a lot more about the game. A cricket ball is a more vicious weapon than a baseball: it is slightly smaller than a baseball, slightly heavier and it is a lot harder. In “test match” cricket, which has traditionally been played during daylight, it is red, whereas in “limited overs” cricket, which is played under floodlights as well as in daylight, it is white. “Test match” and “limited overs” will be explained in due course. The ball has two symmetrical halves held together by a central raised seam, but as the game wears on the players will “work on the ball,” shining one side and allowing the other to become rough so as to exaggerate its aerodynamically induced movement through the air. The ball is not exchanged for another unless it becomes very badly damaged or distorted, or hit so far out of the ground that it is lost; wear on the ball is an integral part of the game as it changes its aerodynamic properties and the way it reacts to the bat and bounces off the pitch. If a ball has to be exchanged for another, a similarly worn one will be selected to replace it.

In both baseball and cricket, the ball can be projected by the pitcher/bowler at up to 100 mph with a baseball typically going maybe 5 mph faster than a cricket ball. The reason for the slower speed in cricket is that the bowler must not bend his or her arm but must project the ball with the windmill action of a straight arm. Whereas the pitcher stands still when the ball is thrown, the bowler, who bowls from 22 yards rather than the pitcher’s 20 yards, runs in to bowl so as to gather speed and rhythm for the unnatural bowling action.

There are many kinds of bowler, but an initial classification turns on the speed of the ball: fast, medium, or slow. Fast bowlers may run up for twenty or more paces before delivering the ball, whereas slow bowlers may take only a couple of steps. The relative effectiveness of the three kinds of bowler depends on the nature of the pitch and the state of the atmosphere. If conditions are just right, slow bowlers, who impart spin so as to make the ball shoot sideways when it bounces, can be “unplayable.” All bowlers can be left- or right-handed, and slow bowlers, otherwise known as “spinners,” can bowl different types of ball as their characteristic weapon. Now one must remember the terms “offside” and “onside,” or “leg-side,” which were defined in figure 2.2 and chapter 3. A right-handed spin-bowler who releases the ball from the index finger side of the hand will tend to spin the ball clockwise as seen from the bowler’s end, and when it bounces it will tend to jag toward the offside of the pitch as defined by a right-handed batter; therefore, such a bowler is known said to bowl “off-spin.” “Leg-spinners” bowl out of the little-finger side of their hand and the ball goes the other way. A “googly” is bowled by an off-spinner who, disguising the action, turns the hand over with the fingers pointing back toward the chest so that the ball turns the opposite way from what is expected, while a “chinaman” is a left-hander’s googly. Medium-paced bowlers can be very effective when the atmosphere is heavy because they can make the ball “swing” through the air—travel in a sideways curve and also jag off the pitch if the ball is held just so. But some sideways aerodynamic movement and nonballistic changes in trajectory in the vertical plane—“dip,” which is mostly the provenance of the spinners—can be employed by all categories of bowler if conditions are right.

Fast bowlers also make the ball jag a little and swing, but one of their chief weapons is intimidation. It is a legitimate part of cricket for a fast bowler to try to hurt or injure a batter by bowling “short” so that the ball rears up and strikes the batter on the hands (gloves are worn but do not give very good protection), the body, or the head. The batter is entitled to try to hit and hurt the fielders who stand very close in the hopes of catching the ball should it loop upward off the bat—fielding positions known, not inappropriately, as “silly mid-off,” “silly mid-on,” or “silly point.” Cricket is not a contact sport, but, given the speed and hardness of the ball and the player’s legitimate intentions, it a more dangerous game than baseball. On November 25, 2014, the Australian International batsman, Philip Hughes, was fatally struck by a ball and died two days later; and there is a list of a dozen recognized names going back in time who have died, while injuries are frequent.

To understand cricket it is probably necessary to understand something of social class. As Collins, who has played cricket at a low level, can attest, standing up to a fast bowler requires a lot of courage: one must not back away as the projectile hurtles toward you but must face up to it and allow yourself to be hit if necessary; one must mutter to oneself, “stay in line,” “elbow up” (which keeps the bat vertical). Top-class batters sometimes have to try to hit a ball projected at their faces and sometimes the ball gets through and rearranges their features. This kind of courage was what was required of the English upper classes who were expected to lead their men “over the top” from the safety of the trenches and walk calmly into a hail of bullets. And, until fairly recently, cricketers would not wear protective headwear or padding except for pads in front of the lower leg, (since allowing the ball to hit the legs is part of the game); nowadays helmets and various other kinds of padding are worn by the batter and any really close-in fielders, but this has not stopped career-ending or even fatal injuries.

The top-class game also lasts for five days and is played while dressed in pure white tailored clothing—and one can see what that means and guess who wasn’t doing the washing and ironing—while the unnatural acts of both bowling and batting are best perfected with long training in top boarding schools—making those initial victories by sides coming from India and the West Indies difficult for some to bear, not to mention the Australians. Batting is unnatural because an “uncultured” swipe at a ball that is bouncing unpredictably will usually result in a miss or a catch, so the ideal stroke is played by keeping the bat vertical with a raised elbow and body behind the ball. The “cover drive,” where the ball as struck in this way slightly “inside out,” with a slightly bent knee so that it disappears toward two o’clock on the off side, is one the most elegant movements in all sport, with batters sometimes holding the pose for a moment after the ball has disappeared. Collins taught himself to play a good cover drive but, unfortunately, couldn’t play any other decent strokes and so did not last long “at the crease.” There is a good literature on cricket’s notorious early class structure with the amateur gentlemen refusing to share their dressing room with the paid players, and so on. Nowadays, that has mostly disappeared.1

But this is only to begin to understand the game; the crucial point is the role of time and the rhythm of the competition. “Test matches” are played between national teams and are the classic form of the game. A test match lasts five days, and its unique feature is that the game is a draw, irrespective of the score, unless all its phases are completed within the allotted time. Incidentally, there are three sessions in a day, each lasting two hours. After the morning session a forty-minute lunch is taken and after the afternoon session tea is taken—the break lasts for twenty minutes. In the old days of village cricket (a village match only lasted a day), the wives would provide a wonderful tea for the players.

The phases that must be completed for a test match not to be a draw comprise two “innings” for each team of eleven players. The British have an “innings” not an “inning,” and a completed innings means, not that every player has had a turn “at bat,” but that every player has had an innings. You have to know how to use the language: thus the “wicket” is not only the stumps, but is also another term for the pitch. And the pitch is not only the wicket, but also the place on the wicket where the ball bounces: one can say: “That ball was pitched too short,” or advise a novice batter “Watch the pitch of the ball.” For those who were following closely and noticed an inconsistency, since there are eleven players on each team but the game requires that two batters be on the field at once, an innings is complete once ten people are out rather than all eleven so an innings can be completed with one player being “not out” and therefore not having completed his or her innings!

In the case of test matches, rain or bad light can shorten the allotted time making a draw more likely. Cricket, at its best, consists of a series of hundreds of violent interactions that are played, overall, at a relaxed pace. Test-match cricket can be deadly dull when batters refuse all risks, and deadly disappointing when bad weather shortens play to such an extent that a tense confrontation is ruined. But when everything works out just so, it is the most tense and exciting game in the world. Such situations can be stage-managed by a captain who is prepared to surrender some of his or her team’s allotted batting rights—cut an innings short before every player has had his or her innings—for the sake of bringing about a result rather than allowing a game to meander to a draw. But “declaring” an innings closed before all the batters are out is fraught with danger because it can offer the other side the chance to win. Thus are created some of the most dramatic moments in sports that can be imagined.

But test-match cricket is too long and too unreliable to bring in enough of the kinds of mass audiences needed for today’s sports, so cricket has adapted by inventing various forms of the “limited overs” game. We have seen that there are two batters playing at once with one bowler projecting the ball from one end, and we know that after six balls have been bowled—an “over”—everything switches, including all the fielders, and a different bowler starts attacking from the other end, bowling at whatever batter happens to have wound up there. That is how it happens that if an odd number of runs are scored off the last ball of an over, the batter who hit the ball that results in the runs being scored will find him- or herself still “facing”—in this case facing a different bowler running in from the other end. If there had been no runs or an even number of runs off the last ball of the over, then the other batter would be facing the bowler. And remember that a batter can stay in as long as he or she likes so long as he or she is not out, and there is no need for the batter to try to hit the ball if he or she doesn’t want to. In test cricket the primary job of a batter is to last as long as possible without being out, and this imperative has led to some notoriously flawed cricket careers where certain batters would decide that not being out and improving their “batting average” are more important than winning the game for the team. Even though one is less likely to be out if one does not try to score runs, and even though there is nothing in the rules to make you score runs, if runs are not scored at a reasonable pace your team can never win. There have certainly been cases where notoriously slow-scoring batters have been deliberately “run out” by their teammate who is batting at the other end. In test-match cricket, batters have survived for two days and scored 500 runs, though a “century”—100 runs—is what every top batter aims for when they get their turn at the wicket. (Collins never made it to 50 and still remembers the flinch in the face of a fast ball that cost him his wicket the one time he was about to achieve that landmark score!)

Back to limited overs. In the pure form of the game—the test match—the duration is set by the clock, but in limited overs games each side is allowed to bowl a certain number of overs: 50 each in the one-day game, and 20 each in the 20/20 game, which is completed in an evening. The game is completed when both sides have bowled their overs. There are no draws, only the remote possibility of a tie if both sides score the same number of runs. The onus on the batting team becomes to score as many runs as possible in the course of the allotted overs. Limited-overs cricket has, therefore, become frenetic and sweaty and, correspondingly, is played in ugly colored uniforms rather than beautiful white clothing.

One way of scoring runs has already been explained—hit the ball and run before anyone can get the ball back from the outfield and break the wicket—but the majority of runs in most matches will be scored by hitting the ball across the “boundary”—a rope or other marker that defines the outer edge of the playing area. Four runs are scored if the ball crosses the boundary and six runs if the ball crosses the boundary in the air before bouncing: a “six” then, is the equivalent of a home run. In test-match cricket, sixes were a rarity because the aim was to keep the ball on the ground so it could not be caught; this is where a lot of the game’s elegance came from—a stroke designed to keep the ball on the ground is a beautiful thing. In limited-overs cricket, however, sixes are important, and the strokes required to hit them are often more like the baseball batter’s swipe. Before this becomes too snobby, let it be said that the feedback from limited-overs cricket to test-match cricket, in terms of willingness to take risks and the skills required to execute risky shots without being out, has been greatly beneficial to the longer game and improved the typical test-match as a spectacle.

So long as conditions can be created for the execution of the basic transaction of the bowler and the batters, cricket can take any form. Thus most kids in countries where cricket is popular will play their first games with someone bowling a tennis ball in the street at someone defending pile of coats with a bat cut out of a plank. At the top end, Collins has seen an all-star game played between retired professionals on a baseball field in Texas. Because baseball fields are smaller than cricket grounds, that game too had to be “one-ended,” like the street game. But it provided a wonderful display of six-hitting hugely appreciated in a stadium packed with fans—admittedly they seemed to be mostly of Indian descent. But perhaps this very baseball-like version of the game will catch on in in the United States—it is much more action packed than baseball itself.

Figure A.6 A run out in a limited-overs game with colored uniforms.

Table A.1 The popularity of some top sports according to website usage