It was during that period that I painted my MOTHER AND CHILD series. As a young mother, I believed I had a lot to say about the mother-child relationship. I felt that while that relationship was mostly positive, it also had its dark side. Each of the paintings in the

MY LIFE INTO ART

series was to portray a different aspect of the mother-child relationship. The series was to consist of large oil paintings, each 40" by 40", rendered in the chiaroscuro technique in oils in earth tones, mostly in raw umber with the mixture of black and white, as needed. The reason I chose earth tones was that I felt they expressed the elemental nature of the mother-child relationship, which was as basic to human life as Mother Earth.

I was pleased with the first few paintings in my MOTHER AND CHILD series. I felt that both the compositions and the color succeeded in conveying my feelings about the mother-child relationship. But when I brought some of these paintings to class for George Dergalis' critique, I was surprised and dismayed at his strong negative reaction to my paintings. He loved the compositions. But, in lieu of my monochromatic earth tones, he wanted me to do the paintings in clashing bright flat colors using all the basic hues of the color circle, with patterns like polka dots and stripes to boot. I soon found out that George Dergalis himself liked to create abstract works, with bright colors and clashing patterns and as many textures as possible. Apparently now that he was not bound by any Museum School guidelines or standards, he felt free to pressure his students to follow his personal way of painting.

I tried to resist George Dergalis' pressure on me to create my paintings in his paintings' image. But he was very sure of himself and controlling, and since I felt I still had something to learn from him by way of various mediums and techniques, I agreed to give his way a try and paint Dergalis versions of my mother-and-child paintings. So while at home I continued creating my earth tone monochromatic mother-and-child paintings, in class I painted new mother-and-child paintings on fresh canvas, using as many flat bright colors and patterns as I could. Of course I no longer brought my mother-and-child home-painted earth tone versions to class for critique. And, as for the class versions I painted, while George Dergalis was delighted with their bright colors and patterns, I felt they were at best merely decorative works, the product of a clever mind that liked to play games but had nothing substantive to say. So, as soon as I finished them and brought them to my house, I destroyed the Dergalis versions of my paintings.

MY LIFE INTO ART

Although I had painted them myself, I did so under duress and could not bear to look at them or even have them around.

Studying under George Dergalis at the Sidney Hill Country Club became increasingly stressful for me. We had a real personality clash. I had followed him from the Museum School to his classes at the Sidney Hill Country Club because I felt that the various mediums and techniques he had taught at the Museum School had broadened my means of self expression and I had hoped that he would now further enhance and encourage my ability to express myself. But he did no such thing. Instead, he tried to have me express his vision, not mine, and there was no way I could allow someone else's vision to be imposed on me.

And so one day, about a year after following him from the Museum School to the Sidney Hill Country Club, I said goodbye to Geroge Dergalis and never studied under him again. Years later, when I was taking classes at the DeCordova Museum Art School in Lincoln Massachusetts, where George Dergalis was teaching part time, I would sometimes walk along the path outside the studio where he was teaching, and, through the screen window wall, I could see all the little Dergalis paintings that his students were creating. But although I myself had closed the door on his attempted tyrannical imposition of his own vision on me, I never forgot all the good things I learned from him.

MY LIFE INTO ART

to show for my year there. But now I had worked on several series, such as FLOWERS, PORTRAITS, MOTHER AND CHILD and MYSTIC INTERIORS. I was proud of what I had accomplished in just a couple of short years and wanted to share my accomplishments with my father. I wanted him to be proud of me.

So a few days after we got to London, I showed my father the photographs of my paintings. David and Laura were already asleep, and my father was visiting me in the hotel suite I shared with the children. I handed the album to my father and, as he leafed through it, I tried to explain the why and how of various paintings.

"Very nice," my father said after he finished looking through the photos. "But I know nothing about art. Maybe you should show the pictures to Mother."

I wasn't sure I wanted to show the photos of my paintings to my mother. Because I had put my innermost thoughts and feelings into them, I considered them too personal to share with her. After years of watching her mistreating Bob, Saul and me, I felt alienated from her. I also had a sense that she was simply too judgmental to deal with, and that whatever she might have to say could not be taken seriously. But I did want to please my father, so a few days later, I showed my little album of photographs to my mother. It was hard to get hold of her, since she spent most of her days in London either consulting with doctors or shopping. But one evening I did manage to catch a few minutes with her in my parents' suite. She studied the photographs rather quickly and when she was done she said, "I still don't understand why you are not pursuing a serious career. With all the education you have had, there must be a way you can have a career and make a name for yourself and at the same time earn some income for your family. I don't imagine that a law professor's job brings in all that much."

To my astonishment, my mother's reaction to my paintings upset me. I had no idea that deep inside I was eager to please not only my father but my mother as well. It seemed that I wanted her to be proud of me, too, although I did not know why it should matter, as she had always seemed impossible to please. After hearing her response, I felt like breaking into tears. But I maintained my composure.

MY LIFE INTO ART

Since my mother was preoccupied with her own plans, my father, David, Laura and I were on our own, exploring various areas of London, enjoying feeding the pigeons in Trafalgar Square, watching the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace and even visiting the London Zoo. My father was a delight to spend the day with, energetic, friendly and always positive and uplifting. Each day he had a plan for us to explore new things, working out his plans for us around his business commitments. The children and I had a wonderful time with him and I hated to see our London holiday come to an end.

When I returned home, I completed the MYSTIC INTERIORS series. I felt that through these paintings, I had successfully expressed some of my feelings and questions about God. So that when I enrolled in a life class that fall at the DeCordova Museum Art School in Lincoln, Massachusetts, I was eager to hear what my new art teacher had to say about these as well as my other paintings, including my monochromatic MOTHER AND CHILD series. My new teacher's name was King Coffin, and he taught full time at the Museum School, where he had been a member of the full-time faculty for many years. But he was also conducting classes at DeCordova in his spare time. I had heard good things about him from some of my fellow students at the Museum School, and since I could not study under him at the Museum School unless I enrolled there as a full time day student, something I was not ready to do at that time, I opted to take his course at DeCordova. Lincoln turned out to be much more accessible from my house in Newton than Boston was.

I was interested in the life class because I felt that, as an artist, I could use the movement of the human figure to convey important ideas and feelings. I had tried to do so in my MOTHER AND CHILD series as well as in several other paintings I had done after completing that series. King Coffin's life class at DeCordova turned out to be beyond my wildest expectations. The teacher was a master at eliciting what was best in each student. Usually, he would have the model assume short poses, some only a minute or two long, for the first two hours of the class, and in the last hour he would have the model assume a single pose, so students could use drawing or painting or collage or whatever other medium they wished to use and create an

MY LIFE INTO ART

artwork based on the long pose. The short poses were intended to help the students "warm up" by having a chance to quickly capture the basic movement of the figure, without having the time to be distracted by details. It was also important for the students to pay close attention to the layout of the figure within the confines of their pad. In later years I used many of the quick studies I did in King Coffin's life classes to represent figures in my paintings, graphics, wall hangings and even in ceramic sculptures.

The life course was one of many life courses I took from King Coffin during my years of studying at the DeCordova Museum Art School in Lincoln. Over the years I also enrolled in several of his portrait courses, where he was just as broad-minded about the students' work as he was in the life class. What I liked best about King Coffin was that he did not compel his students to follow a particular path. Rather, he encouraged them to experiment and find their own way, and he was knowledgeable enough to understand what they were trying to do and why. King Coffin gave his students help when it was needed. He offered guidance without being overpowering. In the latter respect he was just the opposite of George Dergalis, whose vision was tunnellike and who seemed to believe that his job as an art teacher required him to force his students into the Dergalis mold. I remember that at one point, after I had studied with King Coffin for a number of years, I invited him to my house to see my paintings. It was impossible for me to bring more than two or three completed smaller paintings with me to class at any one time for his critique because more than that would not fit into my car, and some of the larger paintings would not fit at all. Besides, I wanted King Coffin to see my oeuvre as a whole and tell me what he thought. At that time David and Laura were a little older and I was wondering whether I should enroll in the Museum School as a full-time day student to make sure that I received a thorough art education. When King Coffin came to my house, I had several hundreds of paintings, as I painted pretty much full time while David and Laura were at school. After studying my works, Prof. Coffin told me that I was better off continuing to do what I was doing rather than enroll in the Museum School full time.

MY LIFE INTO ART

"But why?" I asked him, surprised that, being a long-time member of the Museum School faculty, he would discourage me from enrolling there full time. "I remember that D.A. told me that you encouraged her to go to the Museum School full time," I added, remembering a conversation I once had with a classmate of mine at DeCordova. The following semester she no longer showed up for classes, and I heard from other DeCordova classmates that she was now a full-time student at the Museum School.

"Because you are different. You are unique," King Coffin said. "You have your own ideas and your own way of painting. I wouldn't want you to lose your originality, the way so many Museum School students unfortunately do."

It was in 1968 that Bob and I realized that we needed to add a studio to our house if I was to continue painting. I had been painting in our bedroom, using an easel to place my canvas on and utilizing my little desk for my brushes, oil paints and turpentine. The smell of the paints and turpentine permeated the bedroom and there was always a risk that the freshly painted canvas would be knocked off the easel. There was also very little space to store my finished paintings. We decided to add a studio to the back of our house that would be large enough and convenient enough for me to paint in and store my rapidly growing store of paintings for years to come. I drew the plans for the studio myself, specifying doorways and windows and storage cabinets and the like. I wanted very high ceilings so I could hang up even very large paintings, and good enough lighting so I did not have to rely exclusively on sunlight, since it was not always available, especially because I wanted to be able to sometimes paint at night. In order to have the studio, we needed to do considerable interior remodeling of the existing bedrooms so that we could have a hallway leading into the studio. In my plans I included a half-bath off the studio and a sink area, as well as a small hallway and exterior door that opened out onto the driveway, so I could easily take my paintings to class and bring them in, without having to go through the house.

We found a local contractor-carpenter, who studied the plans and promised to finish the construction within two months. Although he was an excellent craftsman, I soon found out, to my dismay, that he

MY LIFE INTO ART

was in the habit of quitting work around noon every day, and not showing up for work in the afternoon. I was later told that the reason he failed to show up in the afternoon was that he was having an affair with a married woman from our neighborhood, and the only time he could safely see her was during the afternoon, when her husband was away working. Whatever the contractor's reason, the construction of my studio dragged on and on and was finally finished about six, rather than two, months after it began. It was difficult for me to do much painting while the construction was going on because of the constant interruptions from the contractor and his sub-contractors. But I did manage to escape once a week and go to DeCordova to attend classes.

During that time I learned that my father had a heart attack and was first hospitalized and then was recuperating at home. A few years before, my parents had purchased an additional, roof-top apartment in our apartment building on Pevsner Street in Haifa, which my mother had tastefully decorated inside and out, including having tropical plants planted in large containers all around the terrace so that the area looked like a beautiful tropical garden. The terrace was also high enough above the neighboring apartment buildings as to offer a magnificent view of Haifa Bay and the towns of Acre and Nahariya to the north and, beyond that, Mount Hermon. It was in that beautiful setting that my father spent his days recovering from his heart attack.

As soon as I heard that my father had been stricken, I wanted to go and visit him. I called my mother and told her I wanted to see him. But my mother strenuously objected, telling me that a visit from me would be so exciting for my father that it would endanger his health. Of course the last thing I wanted to do was to endanger my father's health. So I waited a week or two and again expressed my desire to visit my father. Again my mother was emphatic that I should not come. I have often wondered whether her objection was based on genuine concern for my father's health or on her own self-indulgent convenience.

My father finally recovered enough from his heart attack so that his doctor gave him permission to go to Switzerland for a couple of weeks. It seems that my father had an important law client in Switzerland, for whom my father had successfully concluded an

MY LIFE INTO ART

important case, and the time had come for the client to pay my father what he owed him, which was a substantial amount of money. My mother was eager to get my father to go to Switzerland so that he could meet with his client and get paid. My father called me and invited me to join him and my mother in Switzerland, where we could spend a week together. I had not seen my father since our visit in London the year before, and, because of his recent illness, I was especially eager to see him. Bob was kind enough to agree to take care of David and Laura during my absence, and I packed my suitcase to leave.

The night before I was scheduled to fly to Switzerland, a phone call came from my Uncle Haim, the husband of my father's sister, Raya, informing me that my father had suddenly and unexpectedly passed away. It seems that my father had been put by his doctor on blood-thinning medication, and the blood thinning medication resulted in internal bleeding, which was the cause of his death.

I immediately changed flight plans and went to Israel to attend my father's funeral instead of to Switzerland to have a holiday with him. It is required by the Jewish tradition to bury the dead as soon as possible after death occurs. When I got to Israel I found my mother hysterical. The nurses at the Elisha Hospital, where my father died and where his body was to be picked up for the funeral, told me that after my father passed away, my mother cursed him loudly and repeatedly for having abandoned her before their scheduled trip to Switzerland. The nurses said they had never seen such an outburst against a deceased person from anyone any time before.

MY LIFE INTO ART

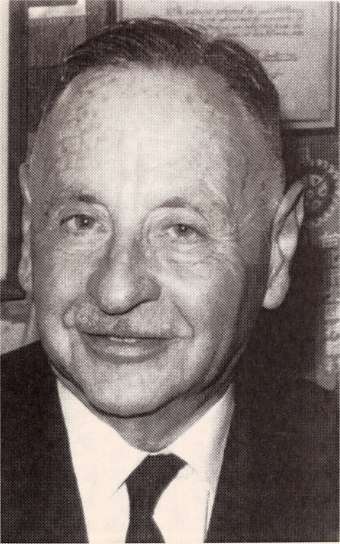

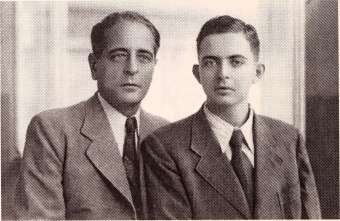

JUDITH'S FATHER, 1960s

This is the way my father looked

when my children and J enjoyed our European holidays with him.

MY LIFE INTO ART

JUDITH, WG8

(hoked sad in thh passport photograph taken in Haifa when I went there to attend my father's JunemL

MY LIFE INTO ART

before my mother began the renovations on the house, and told me that my mother was threatening to commit suicide if I didn't immediately give up any claims I might have to the house. Of course I immediately told my mother's lawyer that I would gladly forego my share in the house. Much as I disapproved of my mother's ways, I was not prepared to be responsible for her suicide.

My father's sudden death shook me to the core. I had second thoughts about the way I had chosen to lead my life. I was especially sorry that I chose to leave Israel back in 1955, after I had spent seven long years studying in America and dreaming of returning to my homeland, and finally going back and bringing Bob with me. I couldn't blame Bob for our return to America, since he was very happy in Jerusalem and would have stayed there forever if it was up to him. I had only myself to blame for missing out on a dozen years I could have spent following in Saul's footsteps and being close to my father and making him happy and proud.

In my grief, I threw myself into my painting more than ever. I painted some self portraits, through which I could explore my own psyche. I also painted some portraits of my father. I had never painted a portrait of him before, but now I knew I had to give expression to the way I felt about him.

The idea for how to do so came to me one day while I was in a fabric shop, looking for some fabric to use for sewing play clothes for Laura. I wanted the fabric to be so "busy" that it would not show stains. The fabric shop I was visiting had clothing fabrics as well as home decorating fabrics, and, among the latter, I discovered an earth tone print, with criss-crossing undulating lines done in brown as well as in black and gray all on a white ground. It did not take me long to realize that the fabric was patterned after Jackson Pollock's abstract drip-painting compositions. The fabric was made of sturdy cotton, and it seemed perfect for play clothes for Laura. But the longer I looked at the fabric, the more I felt that rather than using it for Laura's play clothes, I could use it for painting portraits of my father. I didn't have a clear idea of how I would do so, but I instinctively felt that I had found the right fabric for my father's portraits, and purchased several yards of the Pollock-print fabric.

MY LIFE INTO ART

I had never heard of any fine art painting done on commercially printed fabric, but I didn't see why it could not be done. After all, oil paintings were usually done on canvas, which might be cotton or linen, and the way that the oil was kept separate from the raw canvas was by means of a layer of gesso. I knew that oils are acidic and, if allowed to touch the raw fabric directly, they would eventually destroy it. But I could apply gesso to those parts of the commercially printed fabric that I wanted to paint on and leave the other parts of the print intact, so that the print would become part of the painting's design. There was no point in using commercially printed fabric if I wanted to cover it all with gesso and paint all over it, since that would be tantamount to simply using a blank canvas.

When I brought the Pollock print fabric home, I cut a piece of it and stretched it on 24" by 18" stretchers. I then proceeded to paint white gesso over some of the white spaces between Pollock's drip lines so that I could paint my father's portrait on the gessoed white parts. Since the portrait would not cover the Pollock drip lines themselves but only some of the spaces between them, the portrait, which would be a head-on view of my father, would make it seem that my father was peering from behind the printed Pollock lines.

As I was using a fabric only parts of which were gessoed, I had to be careful not to let my oil paints touch the ungessoed parts, which consisted mainly of the original Pollock printed lines. To make sure I portrayed my father's likeness correctly, I used a photograph of him taken at a photographic studio in Haifa in the 1930s, when I was a little girl. It was one of my favorite photographs of him, as it expressed, through the look in his eyes, not only his great wisdom but his kindness as well. I intended to portray my father in naturalistic colors and show his beautiful blue eyes looking straight ahead at the viewer, peering wisely and steadily through the maze of reality represented by Pollock's drip lines that ran helter-skelter over the fabric.

One day, while I was working on the portrait, the doorbell rang. It was my neighbors' daughter, Susan, who had come for a visit. Susan was then a teenager, the oldest of three children. She was quite bright and I always enjoyed exchanging a few words with her, usually at the

MY LIFE INTO ART

front door or when I happened to be outside and see her. This time, since I was engrossed in working on my father's portrait, I invited Susan into my studio so I could continue working while speaking to her. I had my father's portrait on the floor easel in my studio, as usual, and as soon as Susan entered the studio and noticed it, she stopped short and studied it for a minute or two. Then she said, "But Mrs. Liberman, how do you paint behind the lines?" I couldn't help smiling. I explained to Susan that although it might appear otherwise, I was not painting behind the lines but only between them. But I was glad that she had read the painting correctly, as if my father was behind the lines, looking steadily through the maze of the world.

This portrait of my father was the first work of art I ever exhibited publicly. Shortly after finishing it, I wrote to Dr. Ruben Hecht, a friend of my father's in Israel and the owner of the Dagon Silo Corporation, a grain elevator company in Haifa whose attorney my father had been, and offered to send Dr. Hecht my painting, to be hung at Dagon's beautiful lobby in my father's memory. Dr. Hecht was, among other things, an avid art collector, and years later founded the Hecht Museum at Haifa University. After I sent Dr. Hecht a photograph of the portrait of my father, he responded positively to my suggestion that he display it at the Dagon lobby, but said he could not do so permanently since the Dagon lobby's art display was dedicated to antique vessels and other artifacts relevant to grain cultivation and storage in ancient Israel, in other words, to a display that was connected to Dagon's function. Dr. Hecht suggested that after my father's portrait is exhibited at Dagon for a couple of months, it be sent to Beit Jabotinsky, a museum in Tel Aviv associated with the Revisionist party of Israel, of which my father had been a member. After my father's death, my mother donated my father's extensive library to Beit Jabotinsky, and it seemed fitting that my father's portrait be hung in the museum's library, amidst his books. Beit Jabotinsky agreed and I sent my Pollock-print portrait of my father to Dagon. I called the portrait "DOCTOR ABRAHAM WEINSHALL, MY FATHER."

Dr. Hecht was impressed enough with the portrait to include a full-color reproduction of it in the brochure he published about my

MY LIFE INTO ART

father in commemoration of the second anniversary of my father's death. Writing about my father in the brochure, Dr. Hecht said:

"In him were combined both professional conscience and national awareness and, even in his legal work, he cared for the public weal. He only represented clients whose interests were not at variance with these principles; if these conflicted with his convictions, he declined the case. He only undertook law suits when he was convinced of their justness, and he treated everybody equally, regardless of person. He was, therefore, esteemed by Jews, Arabs and all religious communities alike. Among his famous legal cases were those of the heirs of Sultan Abdul Hamid against the Mandatory Government concerning land, and the inheritance cases of Michael Pollak and of the Litwinsky family.

He frequently accepted most unpopular cases, where others lacked the courage, in order to help the weak against the strong.

He was never a cold, strict man of law. The human aspect was always decisive for him. It often happened that he realized that a case could be won on a legal basis but not on a moral one, and then he declined it. However, whenever he recognized the moral weight of a case which legally seemed almost hopeless, he undertook it wholeheartedly. He conducted many lawsuits in the National or Public interest, purely for the sake of justice, frequently with little or no remuneration, including cases for the National Institutions.

Of special importance for the development of the country was his activity over many years for the reclamation of lands, when he represented the National Institutions and the Jewish National Fund at the time of the acquisition of large parts of the (Valley of) Jezreel, (the Valley of) Zevulun and Western Galilee. Many kibbutzim owe the possibility of their existence and development to his effort. It was fascinating to hear him tell how he, together with E. Soskin and J. Loewy, acquired the land on which Nahariya stands today.

Often one had to argue with Dr. Weinshall that he should not forego his fees or take much too little for his great investment of effort and time; for he never did anything in a superficial way, but devoted himself, thoroughly and comprehensively, to every activity.

MY LIFE INTO ART

In addition, he was legal adviser to organizations like the Baha 7 Community, Barclays Bank and the Dagon Silo Company. In the case of Dagon and its affiliated companies he participated actively from the beginning, not only as Legal Advisor but also as one of the Founders, Member of the Board of Directors and Member of the Executive Committee. His well-considered counsel and untiring efforts helped to overcome the numerous difficulties encountered by Dagon and to develop it into an important economic institution.

In every task which he undertook, he was conscientious, devoted and thorough. He developed new horizons, fighting fearlessly for what he felt and recognized to be just, untiring in his perseverance and thoroughness. He combined great knowledge and a capacity for deep analytical thought with humaneness and objectivity, which were so strong that he could forego all rhetoric.

When, after the establishment of the State, Mr. Ben Gurion offered Dr. Weinshall the post of a Justice of the High Court, he declined the offer, in order to remain independent and to be active in politics. It is to be regretted that this man was never called to fill one of those tasks - such as that of Minister of Justice or of Foreign Affairs - in which he, with his abilities, could have contributed even more for the benefit of the people. In Dr. Weinshall we found the rare combination of political consciousness and complete integrity...

...Whatever public office he assumed, he put his whole mind to it. In Haifa he was co-founder and Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Japanese Museum; co-founder of the Haifa-Antwerp Friendship League; P/President of the Rotary Club, where he introduced activities for f Good Citizenship 9 , 'Youth Responsibility and Education'; member of the Board of the Israel-America Friendship League, and very active in the Jabotinsky Lodge, of which he was President for some time. He was a member of the B f nai Brith Lodge, and was made an Honorary Citizen of Haifa.

Dr. Weinshall was indeed an unusual personality with boundless energy, capable of enthusiasm, youthful and vigorous to the end of his life. He was upright and just, well-balanced and unbiased. Often he was sought as arbitrator. His were the highest

MY LIFE INTO ART

personal qualities and talents; he was quick-witted with a sharp analytic mind which always penetrated to the roots of the problem. He elicited the essential points, making them clear and easily understood.

He recoiled from opportunism. He paid dearly for his devotion to the revisionist ideal and suffered many personal and political hardships from the 'Establishment 9 because of his convictions. The Mandatory Government did not overlook him either and detained him in Latrun, together with political friends and adversaries.

He was always polite and friendly, at times almost shy, unfailingly modest and sensitive, full of charm and generosity, always tactful, never rude or raising his voice. Love for his fellow-men shone from his kind eyes.

Only his friends knew that until the last his life was overshadowed by the untimely death in action in the War of Liberation of his beloved son Saul. Solace came to him through his daughter Judith and her talented children.

He knew how to listen and to give generously of his well-balanced and helpful advice. Upright and honest, with a strong social conscience, he was one of the few who lived faithfully in accordance with a well thought out philosophy of life.

To use a Herzl-word - Dr. Weinshall was a true f Diener am Licht' (Servant to the Light), one of the 'Old Guard' of Russian Zionists, one of the last knights, who will live on as a shining example. ft

The portrait of my father which I had painted on the Pollock-print fabric was displayed at Dagon for a while. Although I was delighted to have the portrait on public display in Israel, I had become so attached to it during the months after I finished it and before I shipped it to Israel that I decided to paint a similar portrait of my father on the Pollock-print fabric, which I had fortunately purchased several yards of, simply for me to be able to enjoy. The second painting came out similar to the first but not quite as well, and I painted another and another. But I was not as pleased with any of these portraits of my father as I was with the first. It was not only the matter of the

MY LIFE INTO ART

particular configuration of criss-crossing drip lines that was different in each painting, but also the expression in my father's eyes. For some reason, I could never duplicate the expression of wisdom and kindness in my father's eyes that I had managed to capture in the first portrait.

After the portrait was shown at Dagon in Haifa, Dr. Hecht shipped it, as planned, to Beit Jabotinsky in Tel Aviv so it could be hung amidst my father's books at the Beit Jabotinsky library. But, as I found out years later when I visited Beit Jabotinsky during a trip to Israel, the portrait of my father was never hung in the library which housed his books, as it was supposed to be. To my dismay, I found out that those in charge at Beit Jabotinsky had no idea that the portrait was supposed to be permanently displayed in the library or even where the portrait was. When, with my help, the portrait was finally discovered to be lying abandoned in one of the storage rooms in the basement of Beit Jabotinsky, I took it back and hung it in my home, where I have had an opportunity to contemplate it every day and reflect about my great fortune in having had the father I did and in having had the opportunity to love him and be loved by him for all those years.

A few years after my father died, I took a course in autobiographical writing at the Boston Center for Adult Education. One of the assignments given by the teacher was for the students to write a fable about an important person in our life, past or present. The assignment made me think about my father and the important legacy he left behind, not only in Israel but also in the lives of all who knew him, including mine. I decided to write my fable about him. I had no idea what my fable would be, but as soon as I sat down to write, a fable simply popped into my head in the form of visual images that told a story. This is what I wrote:

"It was winter, and it was icy cold. An old bird huddled against a tree trunk. The old bird would have liked to fly to a nice, warm place, but he was too old and too sick to fly. That was why the old bird had not flown south this winter with all the other birds. That was why he was here all alone.

But no matter; he would try to forget his troubles and he would sing. He could still remember what happened long ago. He

MY LIFE INTO ART

was young when it happened, and was returning from his first winter journey with his father.

As they landed, music filled the air. It was the sound of many birds chirping and singing. He had turned to his father to ask where all those sounds came from. His father said, 'Those are the frozen sounds of dying birds, each bird's last song, thawing in the spring sun/

So now, sitting alone, the old bird opened his beak and chirped. No living creature could hear him. Yet he chirped on and on, singing his song. The sounds of his singing seemed to freeze in the air. But he kept on with his tune until he fell dead, his beak frozen open.

When spring came, the birds returned from their winter journey. And they heard music in the air all around the tree. A little bird turned to his father and asked, 'Father, where does that beautiful music come from?' And the little bird's father replied, 'These are the frozen sounds of a dying bird, his last song, thawing in the spring sun.'"

The following week, when the students assembled in class, our teacher asked each of us to read aloud the fable we had written for our assignment. I felt uneasy about having to read mine aloud in front of a group of strangers, because my fable was so intimate and personal. But, when my turn came, I gathered the courage and read my fable to the class. After I was done reading, one of my fellow students, an older lady, commented that the story would make an excellent children's book. It seems that her grandchildren had recently lost their father in a car accident, and she felt that if a story like mine had been available to read to them, they might have had an easier time dealing with their father's death.

The idea of making my fable into a children's book and memorializing my father in that way appealed to me, and for the next six months I worked on illustrations for my story. I instinctively felt that the story should be illustrated in black-and-white rather than in color because black-and-white would convey the contrast between life and death more effectively. I also felt that the story should be

MY LIFE INTO ART

illustrated with woodblock prints, which I had always found to be a wonderful medium for conveying subjects starkly, especially when this was done in black-and-white. So for the next six months I carved large pinewood blocks to illustrate my fable. I had gone to the Book Fair and studied children's books to get an idea of the number of pages customary in children's books and other related matters, and decided that mine should be a 32-page book, which meant that, in addition to the cover illustration, I would have to create sixteen block prints, the vast majority of which would be double-page ones,

When I was done carving the wood blocks and printing them in black printing ink on white Japanese rice paper, I took the illustrations, which were rather large, to a photocopying establishment to get copies of them made that were reduced in size. I used the photocopies of my illustrations to type up the appropriate words of the story on each illustration and created some book mockups containing the story and illustrations so I could have them available, in addition to the typed story and original illustrations, to send to publishers. I thought I would try a Boston area publisher because that would be more convenient for me to deal with, and, after speaking to the elderly lady editor in charge of children's books at Little Brown and Company, a local publisher, about my proposed book, I sent the materials out to her. She promised to get back to me with her answer within six weeks. At that time it was customary to send a manuscript to only one publisher at a time and wait until that publisher was heard from, and only contact another publisher if the first publisher rejected the manuscript. I waited for months to hear from Little Brown, hoping that the publisher's long silence was a sign of good news. I was wrong. After months of waiting, I received a package from Little Brown, containing my materials and a rejection letter signed by the lady editor. I don't remember whether it was the letter itself that gave Little Brown's reason for rejecting my proposed book, or whether it was something I learned in a follow-up telephone call that I made to the lady editor at Little Brown after I received the rejection letter. But I do remember clearly the reason she gave for rejecting my book proposal: "What child would be interested in an old bird?"

MY LIFE INTO ART

Although I was tempted to give up, I recovered enough to call Addison-Wesley, another local publisher, located in North Reading, Massachusetts. Addison-Wesley was primarily a publisher of educational materials, textbooks and the like, but in the mid-1970s, when I was looking for a publisher for my children's book, Addison-Wesley had a children's book division which, I believe, was called "Addisonian Press." This time I heard from the publisher within a week of sending out my manuscript and illustrations, and the answer was positive.

The editor of the children's book division at Addison-Wesley wanted to meet me in person as soon as possible after reading my fable and seeing the illustrations. I still remember how enthused he was about the prospect of publishing my book. One of the first questions he asked me when I came into his office was, "Tell me, what kind of bird is it?" Of course I had no idea what kind of bird the bird in my fable was. It looked a bit like a starling in my illustrations, but, when writing the book and even while doing my illustrations, I had in mind a rather abstract idea of a bird rather than a specific specie. But it was obvious that the editor was eager to find out from me what type of bird this was. So I said, "I really don't know the name in English. I come from Israel." That seemed to satisfy him. I was curious to find out why in the world he asked the question, and later learned that the editor of the children's book division at Addison-Wesley was an avid Ornithologist. Apparently, unlike the lady editor from Little Brown, he loved birds, old and otherwise, and thought that children would love reading about them, too.

Addison-Wesley did a wonderful job designing the book and printing it. The book was called "THE BIRD'S LAST SONG." I was especially pleased that the editor allowed me to include on the front leaf of the book a dedication to my father as follows:

To the memory of

my dear father

DR. ABRAHAM WEINSHALL

this book is dedicated

with love

MY LIFE INTO ART

THE BIRD'S LAST SONG was published in 1976, eight years after my father passed away. Some of the illustrations I created for the book were exhibited as part of the Marigold Garden show of New England illustrators' work at the Boston Public Library in November of that year. I later donated the original wood blocks and illustrations used in the book to the Children's Literature department at the Dodd Center at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, Connecticut.

Shortly after its publication, THE BIRD'S LAST SONG won a citation as one of the fabulous books of the year.

MY LIFE INTO ART

loved learning new things. Bob was also pursuing his long-time interest in investments, which began before we met back in Chicago. He followed the commodity market and the stock market daily, keeping charts of market movements to help him analyze the trends.

With my family thriving, I felt free to dedicate much of my time to art. And for the next fifteen or twenty years, I took courses wherever I found promising ones offered in the Boston area. While I continued studying at the DeCordova Museum Art School, I also took courses at the Massachusetts College of Art, Boston University School for the Arts, the Boston Center for Adult Education, the Cambridge Center for Adult Education, the Brookline and Newton High School Adult Education programs, as well as studying semi-privately under art teachers who taught outside the framework of an institution. I felt I needed to explore as many as possible of the means of expression that were available to an artist so I could use them, as needed, to say what I had to say. Among the courses I enrolled in were block printing, collagraphs, monoprinting, Oriental brush painting, painting on silk, tie dyeing, batik, book illustration, calligraphy, jewelry, casting, ceramic sculpture, stone sculpture, plexiglass, stained glass, watercolor, abstract painting, accidental painting and even interior decorating. I also repeatedly enrolled in King Coffin's life and portrait courses at DeCordova.

One of the courses I took at DeCordova in the early 1970s was a course entitled "Painting from Nature." When I enrolled in that course, I assumed that my classmates and I would spend class time going outdoors so we could create artworks based on some of the beautiful areas, such as the woods or the lake, that surrounded the DeCordova Museum. Instead, the teacher brought to class a basket full of natural objects for us to use as the subject of our artworks. In the teacher's basket were such items as leaves and flowers and sheaves of wheat and branches and shells and rocks. What immediately caught my attention as I took my turn looking through the teacher's basket was a small seal skull. I picked it out of the basket, took it to my table and proceeded to make a pencil drawing of it, carefully depicting its lights and shadows. I loved the seal skull's beautiful, curved lines and the deep shadows that defined some of its cavities. When I returned home, I created an oil

MY LIFE INTO ART

painting based on my pencil drawing of the skull The painting was essentially a portrait of a seal skull. The skull was seen from above and filled most of the area of the canvas. Over the next few months, I painted several versions of the seal skull, using a different hue in each, against a background of deep black and grays. After painting the seal skulls, I proceeded to paint other skulls, such as deer skulls, monkey skulls and turtle skulls, rendering each skull larger than life to fill out most of the space of the canvas, and letting the somber palette express my feelings. I felt that my SKULLS series successfully expressed some of my feelings about death.

After finishing my SKULLS series, I began a new series of paintings. As America was deeply involved in the Vietnam War, the media were full of war images, and I was moved to use some of these images to speak up not just about the Vietnam War but about war in general. The memory of the death of my boyfriend Gerard and of my brother, Saul, in war had never left me, and I knew I could use paintings about the Vietnam War to speak about war generally and about Man's inhumanity to Man. I was especially eager to say something about the way the women - the mothers, the wives, the girlfriends, the sisters - were left behind all alone to grieve long after their loved ones were killed, a subject I had not seen treated in painting but one that was close to my heart. Since the subject loomed so large in my mind, I decided to create large paintings, each 50" by 40", to convey my message. And indeed the first couple of paintings I created in my VIETNAM series were about the women touched by war. One of these paintings was called "WOMAN." It showed an old woman leaning on a cane and seated all hunched over, as if the whole weight of the world was on her back. The other painting was called "MEMORIES" and showed a seated old woman in profile, lost in thought as if she had a lot to reflect upon. Both paintings were rendered mostly in soft blues and grays, to express the melancholy condition of the women that war leaves behind. In the work COFFINS, I explicitly showed a woman grieving over the casket of her loved one. The dark lines and somber colors of that painting expressed the grief that befell surviving women.

MY LIFE INTO ART

What was unique about these paintings was that I instinctively felt that I should use repeated images of my main subject to express the universality of her condition. Therefore in each painting, the grieving woman is represented again and again in images that are similar except for their size, and the whole composition is integrated by the juxtaposition of the repeated images. I used the same idea of repeated images in other works that followed in my VIETNAM series, such as BAYONETS, BUDDIES, EXECUTION, FALLEN, ONE ON ONE, SOLDIER, SMALL CASUALTY, THERE. The technique of repeated images was used even more prominently in two collages that I also created as part of my VIETNAM series. Thus, in my collage AMERICAN FLAG, the stars and stripes of the American flag were made up of repeated images of a wounded soldier with a bandaged head. The images were reproduced in black-and-white from one of my Vietnam paintings, SOLDIER. The same image of the wounded soldier was also used in my collage PARADE, which showed a parade of soldiers with bandaged heads. In both collages, the repeated images underscored the universality of the horrors of war.

While I was creating my Vietnam works, I became more and more eager to show them so I could communicate my message about Man's inhumanity in general and war specifically. I found a gallery right in Newton, called "Gallery of World Art," which agreed to show my Vietnam works on condition that the gallery could also show some of my other, more "salable" works, such as my FLOWERS paintings and my woodcuts. It was 1973. I had been studying art for ten long years and seriously painting for at least seven or eight. This was the very first major solo exhibition of my art. The title of the exhibition was "PAINTINGS AND WOODCUTS." David and Laura invited some of their friends to the opening reception, and Bob was very proud to show off my work to his colleagues and friends.

It was King Coffin, my beloved teacher from DeCordova, who wrote the piece that appeared on the back of the folded invitation card:

"A sculpturally fluid and often sinuous form seen in a conceptual framework of symbolism that carries a compelling message - this, with color usage that heightens the total expression -

MY LIFE INTO ART

has given Judith Liberman 's paintings an intensity of impact that is a rich and elegant treat to the eye and mind of those who may be gallery-weary with the current offerings.

The movement of the forms and the glowing color combine to give an elusive, pulsating sensation. Thoughtful avoidance oftextural and surface 'gimmickry' further strengthen this play of form.

With velvet transitions from one passage to the next, a unique totality of effect is obtained.

If one is interested in the now current and popular controversy about the differences in gender and their influence on the creative process, with Judith Liberman it could be said that this argument becomes transcended. However, the symbolism that she has made her own comes through with such persuasive warmth and life-force feeling, that perhaps here is the eternal feminine under-writing of the creative thrust.

There are other facets to the artist that exploit an intriguing use of fabric. There are prints and woodcuts and she has been currently involved in sculpture; but it is to the painting that I personally return to enjoy the full scope of this unusual artist."

Overall, I was pleased with the exhibition. It gave me a chance to convey to others my innermost thoughts and feelings, especially about war. But there was one event that happened during the exhibition that distressed me, which was that one of my favorite paintings, TIGER LILY, was sold, so I could not take it back home with me. Some neighbors of ours, whom Bob and I had befriended, were eager to buy this painting, and had previously expressed their desire to do so during one of their visits to my studio. I had politely declined their offer, since I was attached to all my paintings and knew that selling one of them would feel to me like selling one of my children. Not only that, but the particular painting that our friends wanted to buy was one of my favorites. It was a 24" by 18" portrait of a tiger lily, done in bright oranges and yellows and using the egg tempera technique with oil paint glazes. The painting depicted one of the tiger lilies in Bob's garden in our back yard. Well, now it seemed that our friends had outsmarted me and bought the painting, which they were unable to purchase directly

MY LIFE INTO ART

from me, during the exhibition, where I could not refuse them since the gallery had insisted, as a precondition for showing my works, that all the works on exhibition be for sale. To this day, I remember my TIGER LILY painting, and to this day I am reluctant to sell my works, although over the years I have had to reconcile myself to having to part with many hundreds of them, largely via donation, in the interest of making sure that my works are owned by public institutions that will preserve and display them for posterity.

Working on my VIETNAM series took its toll on me. Having to think about that war brought back to my mind the war in Israel and my dear ones who had been killed there. Not long after the exhibition of my Vietnam works, I took a sharp turn in my art and escaped into the world of beauty and color. I pretty much stopped using oils and took up acrylics, because their short drying time was more suitable for the works I was planning. I created numerous series of works, both figurative and abstract, whose common denominator was that they gave me an opportunity to express my more "decorative" side. Among these works were some on architectural subjects (such as my NEW INTERIORS and CITYSCAPES), on the human figure (such as FIGURE COMPOSITIONS, WOMEN and PORTRAITS), works based on nature (such as LANDSCAPES, TREES, and FLOWERS), and a series on BOATS. I also created a large series called PRINTPAINTINGS, which was distinguished by its technique, consisting of the repeated use of block printing in lieu of a brush, rather than by a single subject matter. Others of the works I created during the period following my VIETNAM series consisted of abstracted landscapes (such as LANDSCAPES, POSITIVE/NEGATIVE and MOUNTAIN COMPOSITIONS) as well as abstract works such as the LIGHT SERIES, the CHARTS & GRAPHS, the NUMBERS series, the HARMONIOUS RECTANGLES, the KINETIC series and the MAPS. What gave all these works a measure of cohesiveness despite the diversity of subject matter and approach was that saturated color played a key role in all of them. I had always used color expressively. The palette of colors used in most of these paintings expressed an optimistic outlook.

MY LIFE INTO ART

In the early and mid 1970s, I also continued to exhibit my works. In 1975, two years after my premier PAINTINGS AND WOODCUTS exhibition at the Gallery of World Art in Newton, I showed some of my portraits of my father and also self-portraits which were painted on the Pollock-print fabric, in a solo exhibition called PAINTINGS ON PRINTED FABRICS at the West Newton branch of the Newton Free Library, which was Newton's public library. I had joined a cooperative gallery in New York a couple of years earlier, the Ward-Nasse Gallery, where I had a solo exhibition of my WOMEN series in 1975 and of my PRINTPAINTINGS in 1977.

By 1976 I had begun to feel that I would like to teach art, preferably at an elementary school. I knew how much pleasure Bob derived from his law teaching at Boston University Law School and, as I looked back on my year of teaching international law at the School of Law and Economics in Tel Aviv over twenty years earlier, I remembered that although I had not been particularly fond of teaching law, I had enjoyed the process of teaching as it presented the challenge not only of mastering given subject matter but also of using one's best efforts to present it to others in a meaningful way. Our children were now much older. David was nineteen and a student majoring in Math at Boston University, and Laura, although she was only sixteen, was already a student at Harvard, since she had skipped two years in Junior High and High School and had graduated and entered Harvard a couple of years before her eighteenth birthday. I found out that Boston University, the university in whose law school Bob had been teaching for twenty years, had an excellent Master's program in art education, where I could study while having my tuition at least partly remitted since Bob was on the university's faculty.

So in 1976 I enrolled at Boston University School for the Arts as a candidate for the Master's degree in art education. I was delighted to meet my dozen or so classmates who happened to be, with one exception, female, as well as the teachers, especially Mr. Vincent Ferrini, who taught the artisanry courses. Mr. Ferrini's classes met at the School for Artisanry, which was then part of Boston University, and in his class students preparing for a career in art teaching, as our group was, were exposed to a hugely diverse number of arts and crafts that

MY LIFE INTO ART

they might eventually be called upon to teach. One of the important subjects we studied in depth was metalsmithing. I had previously taken several courses in jewelry both at DeCordova and at the Boston Center for Adult Education, but Mr. Ferrini's course was far advanced, as we were required, among other things, to combine various metals and, in addition to creating jewelry, to create three-dimensional metal objects other than jewelry. We also studied weaving, and had to meet the challenge of constructing our own weaving loom out of wood on which to produce our weavings. I don't recall all the other mediums we studied in Mr. Ferrini's class but I do remember that some of them were already familiar to me in view of the numerous courses I had taken over the years, while others were not. My favorite part of the course involved the use of a medium I had never heard about before, the medium of wall hanging, in which fiber, which means fabric, is used for the body of a mostly two-dimensional work, which, when finished, is displayed by being wall-hung. For one of our class assignments in Mr. Ferrini's class we had to create an original wall hanging. The subject I chose for my assignment was Mr. Ferrini conducting our class. My wall hanging was to be humorous. It was 43" by 19" and showed Mr. Ferrini being tugged at by his students, each trying to urgently attract his attention. The names of the students and the teacher were embroidered and the students themselves were portrayed in various poses as they were busy doing their work and reaching for Mr. Ferrini. One of the ways this wall hanging conveyed the essence of Mr. Ferrini's teaching was that, through the use of beads and threads and fabric pieces appliqued onto the background, it echoed the various mediums we had to master in the class such as fabric, wood and even metal. This was the first of many dozens of wall hangings which I was eventually to create, and I was delighted to have an opportunity, years later, to donate the one I had created in Mr. Ferrini's class to the Boston University Special Collections department. I called the wall hanging "BOSTON UNIVERSITY DAYS." Although I never pursued a career in art teaching, beyond doing my student teaching at the Ward School in Newton and receiving my art teaching certification from the State of Massachusetts, I believe that my art might never have reached whatever peaks it eventually did via my creation of wall hangings if it had not

MY LIFE INTO ART

been for the fact that I was introduced to the medium of wall hanging in Vincent Ferrini's class at Boston University.

MY LIFE INTO ART

JUDITH, 1976

A(tdisoit~Wesky Publishing Ok used this photograph

in promoting my hook THE BIRD'S LAST SONG.

MY LIFE INTO ART

JUDITH, B77 This photograph was taken in my old studio after Bob first became ///,

MY LIFE INTO ART

gave a piano concert for his students at the law school shortly after he returned to work.

But fate had something else in store for Bob. About a month after his heart attack, while he was in class teaching, he again felt sick. He was transported to Newton-Wellesley Hospital, where he was diagnosed as having had a stroke. It seems that following his heart attack, a small piece of scar tissue from his damaged heart became detached and floated into his brain, thus causing his stroke. It was the left side of his brain that had been stricken, which affected the right side of his body.

It is painful for me to remember Bob's horror at having had a stroke. For many years he had expected to die young, but he never thought that, instead of dying, he might have to survive and live with a disability. In Bob's case the disability was worse than death. Because of the damage caused by his stroke, he could no longer play the piano. I remember that one day when I was visiting him at the hospital, he told me that he had found out that there was a piano at the hospital, and that he wanted to go and try to play it so he could see whether he was still able to play. He eventually talked one of the doctors into allowing him to go and try out the hospital piano. He was wheeled to the piano by one of the nurses, and he sat in the wheelchair in front of the piano keyboard and tried to play it. His left hand was as agile as ever, but his right hand could barely move. He later told me it felt to him like a club rather than a hand. He had no control over it or over his fingers. When he realized his great loss, Bob burst into tears.

It was the first time I ever saw Bob cry, but it was not the last. His stroke left him with a deep depression. He was no longer the cheerful, optimistic Bob I had always known but a beaten man wishing for death. The doctors and I persuaded him that he should undergo intensive therapy, both physical and occupational, so as to maximize the chances that his right hand would come back so he could play the piano again. And indeed, he worked very hard with the therapists that the Newton Visiting Nurse Association sent to our house almost daily to work with him. But, although I discerned definite improvement in his walking and even in his right hand, so he could at least hold a pen in that hand and write again, his right hand and fingers never regained

MY LIFE INTO ART

the dexterity required to play the piano. So one day, a few months after his stroke, Bob closed the lid on his piano and rarely opened it again.

Bob was back teaching at the law school at the beginning of the following term, while I was finishing up my studies in Boston University's art education program. During my year at Boston University, I had begun assembling materials for my Master's thesis and, after I completed all the courses required for the Master's degree in art education, I began looking for a position as an art teacher at an elementary school. It was not required that a prospective art teacher actually complete the thesis in order to be certified by the State of Massachusetts to teach art but only that the required courses and the Student Teaching be completed, as I had done. After receiving my certification, I decided in the interest of time that I would forego writing the thesis and simply get an art teaching position. Art teaching jobs were few and far between at that time. I was interviewed for a couple of them and had a good chance of being hired. But the more I looked into it, the more I realized that being an art teacher at an elementary school would require the kind of time commitment from me that would not allow me enough time for Bob or for my own art. It was not just the hours required for actually being there and teaching that concerned me, but the hours that would be taken up in driving to the school and back, and the additional hours spent preparing daily lesson plans conscientiously every day after I got back home.

But I felt it would be a good idea for me to get a job. Bob's health meant that we might reach the point where he could no longer work and our income would be cut, so that if we could count on me to bring in some income, that would be a comfort to both of us. At the suggestion of our son, David, who was a talented computer programmer and had worked as a programmer in hospital settings such as the Beth Israel Hospital and New England Medical Center since his teen years, I applied for a position as a programmer at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston, where the job sounded intellectually challenging and the hours were flexible, as programmers were supplied with a computer at their homes and could sometimes work from home. David had himself worked at the Beth Israel Hospital as a programmer when he was still a teenager, and apparently the Computer Medicine

MY LIFE INTO ART

Department at the hospital assumed that if I was smart enough to have raised such a talented computer programmer as David, I was worth hiring. In preparation for the job, I enrolled in a Computer Programming course at Boston University. The course was interesting but it turned out to be quite useless for my job, as the Beth Israel Computer Medicine Department was using MIIS, a dialect of MUMPS, an interactive language, rather than the computer language taught at Boston University and other educational institutions, and liked to provide its programmers with the Department's own in-house training.

I spent about three years as a computer programmer at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston. After my training, I was put in charge of the Radiology system as well as MISAR, the medical research system. While I enjoyed the intellectual challenge of the work, and was gratified to think that if Bob could no longer work, I would be able to at least bring in some income, which I had rarely done before, as time went by I realized that I had put myself in the same uncomfortable situation I had been in when I was teaching law at the School of Law and Economics in Tel Aviv about a quarter of a century before, namely, that while I enjoyed the intellectual challenge of the work, I was not getting from it the emotional satisfaction that I craved. Matters deteriorated to the point where, every day as I was coming to work, I would ask myself: "What in the world am I doing here? Why am I here instead of in my studio, painting?" I had no good answer and the longer I stayed away from painting the more depressed I became. Eventually I found that I had to quit my computer programming job if I was to save myself and not be an emotional burden on Bob.

Although Bob was functioning well at his job at Boston University Law School, he did not regain his optimistic outlook, at least as far as his own predicament was concerned. Just as he had waited for death to strike him after his forty-fourth birthday because his own father had died at the age of forty-four, he now awaited a second stroke. But this time it was not simply waiting to be stricken from year to year. His fear of having another stroke was a daily matter. True, after his first stroke he could no longer play the piano, so it was

MY LIFE INTO ART

not the fear of being unable to play the piano that made him fear a second stroke.

I believe that one of the things that worried him most about the prospect of having a second stroke was the possibility that he would no longer be able to teach. He loved the subjects he was teaching, which were now jurisprudence and constitutional law. His love for his law students had never abated. He remembered the name of every student he had ever taught, although the class size was large and his classes were always packed. He never had any restricted office hours, like other professors did, because his office door was always open to his students. He loved to talk to them not only about their studies and their professional future but about whatever matters they might want him to help them with, no matter how personal. He was repeatedly voted the law students' favorite professor.

But I think that the main reason for his concern about having another stroke was that he feared the effect it would have on me. He had always supported me in whatever I wanted to do and was proud of my accomplishments, whatever they were. His main desire was that I be happy, and he knew how happy I was when I had the opportunity to create art and how unhappy I could become when I was blocked from having a chance to do so. His main fear was that, if he suffered another stroke, I would have to devote my life to taking care of "an invalid," as he put it, even if we could afford to get some help, and he did not want to become a burden on me. His fear of having a second stroke made him reach the point where he simply wanted to die.

Again, fate was cruel to Bob. As he feared, he suffered another stroke in 1982, six years after his first. This time it was the left side of his body that was affected, so that his left hand now joined his right in being unable to play the piano. As before, Bob was stricken while teaching, but this time he was transported to Beth Israel Hospital, which was closer to Boston University Law School than Newton-Wellesley Hospital was. It seems that one of the students enrolled in his class happened to also be a doctor, and when he saw Bob beginning to falter and mumble, he suspected that Bob was having a stroke, and promptly arranged for Bob to be transported to the hospital. I immediately came to see Bob at the emergency ward, where

MY LIFE INTO ART

he was eventually diagnosed as having suffered a stroke. After the diagnosis, Bob was brought up to one of the hospital rooms to be further tested and treated and to have a chance to recuperate enough to be discharged.

But Bob could not wait to get home. He hated being hospitalized. He hated having to take his medications. He hated being fussed over by the doctors and nurses. He hated being treated as a patient and would not accept the fact that he was indeed sick. Although he knew that his doctors wanted him to stay at the hospital a while longer to undergo various tests and treatments, whenever I came to visit him in his hospital room, he would insist that I take him home, which I somehow succeeded in putting off until I realized it was hopeless. One day when I came to visit him, he told me in no uncertain terms that if I did not take him home right there and then, he would simply call a cab. I took him home because I knew there was no way out.

Again, Bob worked very hard at physical and occupational therapy to regain some of the functioning he had lost, this time on the left, rather than the right, side of his body. He also met faithfully with the speech therapist, who visited our house several times a week, because Bob was eager to get back to teaching as soon as possible and realized that he had to regain his ability to speak succinctly before he could do so. After a few months of hard work, he was indeed able to get back to teaching, and he was ecstatic at being able to see his beloved students again.

I was concerned about his driving himself into Boston, where Boston University Law School was located, since I had the impression, when sitting in our car while he drove, that his sense of timing had been affected by his stroke, as he seemed to be unable to maintain a steady speed in driving, and appeared to be increasing and decreasing his speed rather arbitrarily. It was odd that someone who had played the piano so well and had been able to keep such perfect timing should now, after a stroke, have this problem. But I knew how important it was for Bob to feel independent and self-sufficient, and since he left for work very early each day, when the roads were rather empty, and returned from work long before the rush hour, I went along with his

MY LIFE INTO ART

desire to drive himself to the law school and back. Bob never got into an accident and I was glad that my worry was for naught.

Strangely enough, Bob's second stroke seemed to have the opposite effect on him than his first one had. While before, he waited from day to day to be stricken again, this time he seemed to regain some of his positive outlook. I am hard put to explain this, but it has occurred to me that perhaps once he had his second stroke, he realized that no matter how hard he might be hit, he was strong enough to survive. Or perhaps he simply felt that the worst had already happened so that things could not get worse. At any rate, he now spent many of his free hours taking a correspondence course in fiction writing, and wrote short stories, two of which were published in prestigious magazines. He also spent a considerable amount of time planning and tending to his beautiful gardens, which he liked to show off to some of our neighbors, who, like him, were interested in gardening. He loved to play chess all by himself, using our beautiful Israeli hand carved wood chess set, and I used to tease him that perhaps he was playing chess by himself so he could always be sure to win.

One thing that doubtlessly contributed to Bob's, and my, sunnier mood was that our children were thriving. In 1982, our son, David, graduated from the University of Massachusetts Medical School and went to Baylor University in Texas to do his internship. He was to stay in Texas for a number of years, completing his internship and practicing emergency medicine, before returning to Boston around 1985. In 1982, our daughter, Laura, a student at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, got married to her long-time boyfriend, Dr. David Perlman, and Bob and I attended her wedding at a house belonging to the groom's family on Long Island. Laura had met David Perlman during her very first day of classes at Harvard back in 1976. Although David Perlman was then a student at Dartmouth in New Hampshire, he was attending Harvard summer school, which Laura was also attending. The two happened to be enrolled in the same class and happened to be sitting next to each other.

"My name is 'David'," the young man said, introducing himself to Laura.

MY LIFE INTO ART

"My name is 'Laura'," she responded. "I have a brother called 'David'."

"And I have a sister called 'Laura'," David Perlman said.

It seems that their fate was sealed at that first meeting. Although David Perlman returned to Dartmouth at the end of his summer term at Harvard, he and Laura continued to see each other all through Laura's years at Harvard, and, since, after graduating from Dartmouth, David Perlman enrolled at Einstein Medical School in New York, when it came time for Laura to choose a medical school, she chose a school in New York. She went to Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, from which she would graduate with honors in 1984, as she had from Harvard four ears earlier.

After I quit my job as a computer programmer at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston, I slowly returned to creating my art. I worked on a series of TREES as well as LANDSCAPES, both done in a technique I invented for the occasion of creating heavy texture through placing two painted canvases face to face and pulling them apart. Often the technique required me to repaint and pull the canvases apart numerous times before I could see a pattern of a tree or a landscape that I liked. I used a heavy coat of white acrylic on each canvas to create the texture, and I would follow up, after the textured white paint was good and dry, with thin glazes of acrylic paint to create the vibrant colors. Bob was especially fond of these paintings and I continued creating them and showing them to him to lift his spirits. I never ceased to marvel at the fact that Bob, a city boy from Chicago's urban West and South Side, had grown up with a lyrical soul that truly appreciated nature's beauty, whether expressed in his flower gardens or being reflected in my TREES and LANDSCAPES paintings.

By the mid-eighties I felt that Bob was feeling well enough for me to spend the required hours at DeCordova working in the medium of ceramics. I had taken a course in ceramics at Brookline High School's Adult Education program shortly after Bob and I first came to Boston, and later studied ceramic sculpture both at the Boston Center for Adult Education and with Peter Abate, a renowned Museum School sculpture teacher who had been fired from the School at the same time as George Dergalis and was teaching sculpture to small

MY LIFE INTO ART

groups at his studio in Chestnut Hill. Now, in 1985, I felt I wanted to get back to the medium of ceramics and enrolled in a course given by Makoto Yabe, a Japanese master who taught at DeCordova and was highly regarded by the art community as well as by his students. It felt good to get back to DeCordova after a long absence.

Although I had no plans when I enrolled in Makoto's class in 1985 to focus on any specific subject, I found myself creating works that were essentially Judaica, namely, works that bore an inscription or image derived from Jewish history. During that year and the following one, I created numerous works patterned after the coins of ancient Israel, among which my favorite was the coin surreptitiously minted by the Jews around the time of the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD. That coin featured three pomegranates and bore the words "Jerusalem the Holy" ("yerushalayim hakdoshah") in ancient Hebrew. I also used ancient Hebrew, as well as modern Hebrew, on many works featuring the Ten Commandments. Some of my other Judaica subjects were the Star of David, the Menorah and the Burning Bush. I had used some of these subjects in woodcuts years before, but the medium of clay seemed to give these subjects a new life. Although I also created some "universal" works, such as those dealing with mother-and-child or the family or the Tree of Life, I was especially gratified to have an opportunity to get back to my roots and explore Jewish history and Jewish symbols.

During my two years with Makoto, I created many dozens of ceramic works, whether in the form of plaques or mosaics or scrolls or fully three-dimensional sculptures. Bob was always happy to greet me after my day at the DeCordova ceramic studio, and even had the dining table all set with the salads he made for our dinner. He waited patiently as I showered so I could get rid of the clay dust that inevitably covered me. He was always supportive and interested in what I had been doing.

Eventually, long after Bob passed away, I was to donate over one hundred of my ceramic works to Temple Ohabei Shalom in Brookline, Massachusetts, for a permanent exhibition at the Temple's gallery. Since I was eager to have the Temple's Hebrew School use the display to learn about the Jewish past, I wrote an educational brochure

MY LIFE INTO ART

to be used by the teachers so they could integrate the ceramic display into their Hebrew School curriculum. I also donated about two dozen Judaica ceramic works to the Jewish Studies Department at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, Connecticut, for a permanent display at the Dodd Center. Both of these gifts were made by me in memory of my brother, Saul, who was killed in the Israeli War of Independence in 1948 at the age of twenty-one. I also donated several dozens of my Judaica wall-hung ceramics to Jewish Temples around the Boston area in Bob's memory.

MY LIFE INTO ART

Switzerland. I wondered as I walked through the corridors whether the nurses who were currently working there still remembered the incident. Now I found my mother lying quietly in her hospital bed. She seemed out of touch with her surroundings. I don't think she recognized me when I spoke to her. I don't think she saw me or even heard me. She didn't say a word. I was alarmed. This was not the mother I knew. That energetic, vocal, explosive woman I had expected to see was gone. Instead, there was a quiet old woman lying on the pristine white sheets of the hospital bed.

The following morning, I met with my mother's physician. Dr. Riek was a new physician as far as his relationship with my mother was concerned, since he had just been called in after my mother returned to Haifa from her trip to Switzerland and it became apparent to her longtime servant, Mr. Butbull, that something was amiss. The day after she got back, she couldn't see or even sit up. Mr. Butbull summoned emergency help and that was how Dr. Riek got involved.

Dr. Riek was in his sixties or seventies. He had a calm, dignified and thoughtful manner about him. I could tell by his accent that he hailed from Germany. When I asked Dr. Riek what the problem was with my mother, he responded that he did not know, but that he was conducting tests to find out.