Up until now, we have focused exclusively on vocal music, as the vast majority of music that was written down until the sixteenth century was indeed vocal music, sometimes with accompanying instruments. Of course, instrumental music was not absent from society; rather it was generally only used in fanfares or to accompany dancing, and not so much for pure listening or playing. Cultivation of instrumental music by churches and patrons increased significantly in the 1500s, and this is reflected in the preservation and dissemination (aided by printing) of instrumental music from this era and through the creation of new instruments.

Instrumental music in the Renaissance played a role in a variety of cultural situations, from public or religious ceremonies, to entertainment for social gatherings, to accompaniment to dancing. Generally speaking, instrumental music composed in the Renaissance can be divided into five categories: dance music, arrangements of vocal music, arrangements of existing melodies, variations, and abstract instrumental works.

Dancing was one of the high-lights of European society in the Renaissance, and knowledge of dance was expected of those in the upper social classes. In addition to improvising tunes or playing them from memory, instrumentalists also played from printed collections that were published for instrumental groups, lute, or keyboard4. Published dance movement served one of two purposes in the Renaissance. One, dance music written for ensembles (groups of players) was functional in that it simply accompanied dancers. Two, dances pieces for solo lute or keyboard were intended for the enjoyment of the player and/or those listening to the music. Dance music for ensembles was usually simple, with a melody played by a single instrument and accompanied by the rest, while solo dance music was highly stylized, often featuring ornamental and decorative flourishes. In any case, dance music conformed to preexisting dance forms that dictated that a particular meter, tempo, rhythmic pattern, and form be followed.

Paradoxically, another principal source of instrumental music was existing vocal music. While it was previously common for instruments to double the voices of singers in the performance of vocal music, it became increasingly common in the sixteenth century for instrumental ensembles to play vocal music without any voices at all! Keyboardists and lutists, too, would play arrangements of vocal works, either improvising them or playing them from a published manuscript called an intabulation.

Like the vocal music we've examined to this point (such as the imitation mass), instrumental music also incorporated existing melodies in new compositions. It was common for church organists in particular to improvise or compose music based on Gregorian chants or other liturgical melodies. In the Lutheran church, they used German chorales as the source material. Many times, the verses of chorales would alternate between congregational singing and a setting for choir or organ, with organists typically improvising their verses of the chorale.

The ability to improvise on a tune was considered a valuable skill, and the ability to do so while accompanying dancing incredibly important. Variations was the style of improvisation most common during the sixteenth century. An instrumentalist would begin by starting with a specific melody, either existing or newly composed. Then, without any pause or interruption, the instrumentalist would play a series of variations of that theme. This style of instrumental music was useful in creating fresh, interesting takes on existing music, as well as demonstrating the skill and virtuosity of the performer.

While the first four categories of instrumental music are based on vocal or dance music, composers did write abstract instrumental works, instrumental compositions to be played or listened to for their own sake. The principal form of keyboard music written in an improvisatory style was the toccata (from the Italian toccare, “to touch”). The name served to remind the listener that the music was being created by an actual person. Other forms of abstract instrumental music include the ricercare (from the Italian “to seek out”), whose music was imitative and motetlike, and the canzon.

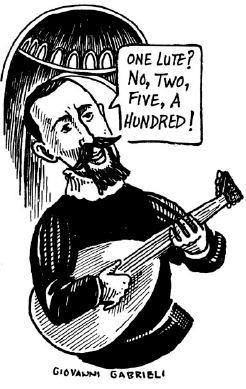

A chapter on instrumental music in the Renaissance would not be complete without mentioning Giovanni Gabrieli (ca.1555-1612). Gabrieli served as a church musician in the glorious St. Mark's Basilica in Venice. His compositions represent the glory of Venetian church music (particularly for the grandiose basilica), with many of his works to be performed by multiple choirs or instrumental ensembles. This genre of composition for multiple choirs was called polychoral motets. Music for divided choirs was not uncommon before Gabrieli, but he took the performing forces to new heights, often writing music for as many as five choirs of different vocal and instrumental timbres. Sometimes, these choirs would be divided spatially as well, perhaps with choirs in the two organ lofts, one on each side of the altar, and yet another choir on the floor.

Regardless of the impetus or occasion for the composition, instrumental music in the sixteenth century took the stage in a major way, setting the scene for future instrumental works including the seventeenth-century sinfonia and the eighteenth-century symphony.

4 In the Renaissance, the principal keyboard instrument was the harpsichord. The harpsichord has one or multiple keyboards called manuals, and pitches were created by a small quill plucking a string when a key was depressed. In comparison, the modern piano creates sound by striking a string with a small hammer.