38

It wasn’t long until the end of the service, but of course we had to drive back in the car through a Christmassy London and say our polite goodnights to the de Warlencourts before we could retire to the library and I could ask Nel what the hell she meant.

‘OK, what? What did you mean in the church?’

‘When?’ asked Shafeen.

‘In the confession,’ I told him. ‘She nearly nipped my arm off, and then said: Where are we?’

‘I didn’t,’ she said. ‘I said, Orare.’

She pronounced it Or-are-ee.

‘What’s an Orare?’ asked Shafeen.

‘You’ve heard it before,’ said Nel. ‘That is, you’ve seen it. Maybe it would make more sense if I wrote it down.’ She went to the blotter on the desk and took up a pencil. She slid a piece of Cumberland Place headed notepaper from its stack and scribbled a word. Shafeen and I craned to look.

ORARE

‘Still no clue,’ I said.

Nel said, ‘Maybe you’d recognise it if I wrote it like this.’

O RARE

Then she added two words:

O RARE BEN JONSON

‘His epitaph,’ I said. ‘Ben Jonson’s epitaph.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘It’s not in English. It’s in Latin. You see? We all said the spacing was funny, and the epitaph was weird. O rare Ben Jonson – it didn’t make sense. But in Latin it does.’ She looked at us both, her eyes very blue. ‘Orare means pray. His gravestone says, “Pray for Ben Jonson”.’

This gave me a shiver.

‘He arranged his own burial, remember?’ said Nel quietly. ‘With the Dean of Westminster. He wrote instructions and paid for it himself. That’s when it was decided he didn’t have enough cash to be buried lying down. And it was then that he must have chosen for his epitaph to be in Latin.’

‘So?’ I said. ‘Churchy things always are.’

‘Not then,’ broke in Shafeen suddenly. ‘Only if you were a Catholic.’

A silence fell and all we could hear was the crackling of the fire and the ticking of the grandfather clock.

‘So at some point,’ I said slowly, ‘Ben Jonson became a Catholic. Even though it was a really dangerous thing to be. I wonder when.’

‘Don’t wonder,’ said Nel, getting out her phone. I was struck, as I had been before in this house, that it was pretty weird to be sitting in the middle of a room full of books and searching for information on a phone. But that was the way of the Savage world – Google was the world’s library now, an infinite digital bookshelf of noughts and ones.

‘You’re not going to believe this,’ said Nel, her face backlit by the Saros. ‘Ben Jonson converted to Catholicism when he was in prison for – wait for it –’

‘– putting on The Isle of Dogs,’ I finished.

‘Yup.’

‘Makes sense, I guess,’ said Shafeen. ‘Queen Elizabeth threw him in jail, so he embraced the religion she hated.’

‘Betcha he’d been leaning that way before that,’ said Nel. ‘Remember, in The Isle of Dogs it was the Catholic rebels who got munched by the hounds. Jonson was pretty critical about that.’

‘True. I wonder if …’ Then I stopped and head-palmed myself so hard it hurt.

‘What?’ said Shafeen.

‘We were looking for a connection between Volpone and Guy Fawkes. It was there in front of us all the time. The connection isn’t the play. It’s the playwright – Ben Jonson himself.’

‘Explain,’ said Shafeen.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘we’ve got two historical figures here: Guy Fawkes and Ben Jonson. They both lived at the same time, right?’

‘Yes,’ said Nel. ‘The Gunpowder Plot was an attempt to kill James I. Ben Jonson was James’s court poet.’

‘And,’ I went on, ‘Professor Nashe told me that Ben Jonson was a spy. He worked for King James and Robert Cecil, but he was playing a double game. I asked Nashe who he spied for, and she said other rebels. She meant Catholics. So what if Jonson and Fawkes are – ya know –’ I said, going all Fargo, ‘connected? What if Ben spied for Guy Fawkes?’ I grabbed Nel’s phone. ‘I bet you any money they knew each other.’ I typed frantically into the search bar.

It took me all of two seconds to find an article on Prospect magazine online entitled ‘Gunpowder, Treason and Jonson.’ I scanned it quickly and could feel my eyes getting wider and wider.

‘Well?’ prompted Shafeen.

‘Did they know each other?’ This from Nel.

‘Know each other?’ And then I told them.

That Ben Jonson and Guy Fawkes had served together in the army in the Netherlands. That as a convicted killer and Catholic, fresh out of jail, Jonson had been an obvious choice to be drawn into the Gunpowder Plot. That he had been to one of the thirteen conspirators’ earliest meetings at a house on the Strand, at the invitation of chief conspirator Robert Catesby. ‘And here’s the best bit,’ I said. ‘When Guy Fawkes rented the cellar under Parliament where he stored the gunpowder, he used the name John Jonson. Fawkes took the surname of his co-conspirator and brother-in-arms. He gave the name Jonson again when he was arrested. And then, of course, Ben was arrested as a suspect too – almost certainly because Fawkes had used his name.’ I imagined another scene in my mental Gunpowder Plot Film – Ben Jonson’s moment of panic when he got that knock at the door; the constables’ torchlight in his face; his pupils contracting; his panicked mind fluttering like a caged bird trying to find an escape. ‘For Ben that would have been his third strike with the law, after The Isle of Dogs and the murder of Gabriel Spenser. He was in deep shit.’

‘So that’s presumably where the spying comes in?’ asked Shafeen. ‘Jonson changed sides and started working for the Crown?’

‘Not quite as scumbag as that,’ I said defensively. ‘He was a double agent.’ I read off the little screen, my eyes one step ahead of my mouth. ‘After Guy Fawkes was caught in the act, with his lantern in Parliament’s cellars, there was no saving him. But Robert Cecil still needed to find the rest of the plotters. He wanted to find a connected Catholic priest to flush out all the other conspirators. But it was a capital offence to be a priest at that time, so Cecil needed a known Catholic to access the secret networks. He called on Ben Jonson, known Catholic, ex-criminal, but court poet.’

‘And did Jonson find anyone?’

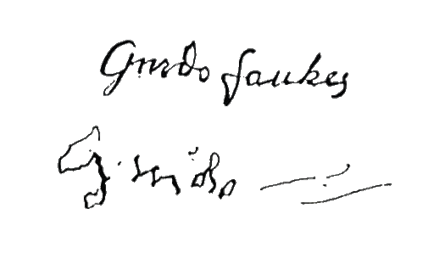

‘You’ll be amazed to learn,’ I said drily, ‘that after trying really hard, he couldn’t find a single priest. I guess as an insider, he was able to protect his Catholic friends. But then, of course, Cecil went another way – he tortured Guy Fawkes so mercilessly that he gave up all the other plotters. Oh Jeez,’ I said, for the search had thrown up something else, something I would rather have not seen. There was a little picture of two signatures, both saying Guido Fawkes. One was written by Fawkes before his torture. The other signature was from his confession, after his muscle and sinew had been stretched on the rack.

It was so apparent that he’d been broken by that dreadful machine of torture – that second, terrible signature was shaky and fragmented and barely legible. Clearly, he could barely put pen to paper.

‘Does it say if Guy Fawkes named Ben as one of the conspirators?’

I scanned the page. ‘No, but I don’t think he can have done. Everyone he did name was executed. Maybe his “brother” was the one person he couldn’t give up.’

Nel said thoughtfully, ‘But Ben Jonson’s involvement in the Gunpowder Plot doesn’t explain what Guy Fawkes has to do with the Order of the Stag, and with Longcross, and the Boxing Day meet. Ty said to see if you can find out about Foxes.’

Then my brain, in that funny stained-glass habit it had of slotting different-coloured thoughts together to make a whole, put everything into place.

The lantern at the Ashmolean with the tell-tale thumbprint.

Nel saying Orare and me mishearing.

The mask the protesters were wearing at Speaker’s Corner.

All those Jacks and Jills at the STAGS Club.

Shafeen saying, They can’t even be bothered to get their names right.

Right there in the middle of all those books, with the firelight on one side of me and the phonelight on the other, I said, ‘What if it wasn’t Fox?’ It was almost a whisper. ‘What if it was Fawkes?’

‘Are you saying,’ asked Shafeen slowly, ‘that Ty overheard something about Guy Fawkes?’

‘Why not?’ I asked. ‘She thought she heard the word fox, and she asked us to find out about it.’

‘And yet,’ said Nel, ‘this whole thing is also connected to foxes. What about that session in the House of Lords? What about the Boxing Day meet? What about the plan to reinstate the foxhunting?’

‘I know,’ I said, staring into the fire as if I might find the answer there. ‘That I can’t explain. But all I’m saying is, it’s possible that whatever the Longcross plot is, it’s somehow connected to that other plot 400 years ago.’

‘Well,’ said Shafeen, ‘there’s only one way to find out what Ty heard. And that’s to ask her. We’ll be seeing her in three days. Only two more sleeps until Christmas.’

It seemed incredible that the next day was Christmas Eve, and I’d be going home. Suddenly I wanted my dad very much. The world of dark cellars and plots was suddenly genuinely frightening. Like a kid, I thought tomorrow would come more quickly if I went to bed.

So I did.