Fryer developed his love of landscape while living in rural Vermont, California and presently in the farmland and mountains of central Utah. He paints primarily in oils but enjoys watercolor, printmaking and digital mediums as well. Fryer has taught fine art and illustration at several universities and art schools, including his alma mater, Brigham Young University, and the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, and he has illustrated for numerous clients in publishing and advertising. His works are of places, objects and people “that have been significant to me.”

The word “sketching” seems to refer mainly to drawings that are done quickly, with little attention to detail and more attention to concept, gesture and important generalities. Most of the drawing I have done in the past few years has been in relation to preparing compositions for paintings. The best drawings, however, are the drawings I have done from life or from the model. But, even the humorous little sketches from my imagination, made to entertain my kids, have been very enjoyable.

I don't routinely draw or sketch every day, and unfortunately not nearly as much as, say, when I was a student or teaching. I tend to go in spurts, and may do nothing but draw for several days at a time, especially when I am preparing compositions for paintings.

Much of my most valuable and satisfying drawing time is spent in sketching the figure. The immediacy of the process never fails to be an amazing, exhilarating experience. The human form is endlessly fascinating, challenging and beautiful.

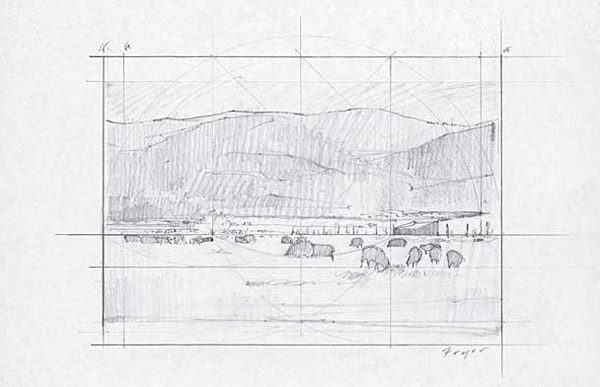

Also, I usually do compositional studies as preparation for paintings. These drawings are rarely what anyone would call finished or resolved, but mainly serve the purpose of solving design and compositional problems. Through these sketches I am able to explore the ratios of the rectangle in which I will work, the placement and flow of elements, and the division and balance of space, planes and masses within in the composition. Much of the initial conception and excitement about the finished piece is contained in the preparatory sketches I make. The essential subjects, patterns, relationships, gesture and flow are expressed and explored at an early stage.

It is rare that anyone sees my sketches or drawings. I don't usually mean for anyone to see them; they are usually only meant to be done.

The materials used to create a drawing are intimately tied to the character of the work. When working from the model, I most frequently use a more tonal medium like compressed or vine charcoal, Conté crayon, graphite stick or Nupastel, though sometimes a sharp graphite pencil is better for smaller drawings. Depending on the drawing, I also enjoy using subtractive methods that require different types of erasers. I use various papers (again, depending on the character of the drawing), but mainly look for something with a moderately smooth tooth — nothing too aggressively rough as to upstage the drawing with its texture, but nothing so smooth that it won't hold the pigment. It is also sometimes enjoyable to work on a gray or tan paper, as it adds an element of value and color to the final piece. I sometimes draw with a brush and pen with ink, or even with powdered graphite with brush and water.

Sketching can be a wonderful connection between the artist, his world, his ideas and values. Drawing — or the creating of any art, really — is best when I enter a profound, meaningful and enjoyable state of mind. It can be a physical, mental and spiritual exercise that is both fatiguing and exhilarating at the same time.

A wonderful benefit I have realized from drawing has been in having a greater ability to express and communicate what I feel and what I think. I also love to analyze the form and relationships of things. But I have to consider, apart from the merits of any finished work, that the process of drawing, the activity itself, is revealing and enlightening to me.

It is rare that anyone sees my sketches or drawings. I don't usually mean for anyone to see them; they are usually only meant to be done. Considering this, I should think that drawing is always freeing, uninhibited and unconstrained. But, unfortunately, I usually fret over even the littlest sketch, judging it as harshly as any finished painting — embarrassed if anyone should see its flaws.

A little planning ahead will certainly help most drawings. Thinking about the balance of elements within the working rectangle, the way the eye will travel and rest, and the relative importance of subjects within the composition should be initial considerations. Of course, the most important element to consider — one that is forgotten too often — is the emotion the subject inspires in you. It is around this emotion that the drawing will be constructed; the emotion will dictate what it wants as expression. Naturally, during the course of the drawing, the artist has to make conscious decisions and judgments: proportion, space, form, line quality, relationships between lines, relationships between adjacent tones, relationships between light and shadow, the quality of the light source. A good drawing (or any work of art, actually) will come after the artist both consciously and intuitively expresses the relative importance, meaning and beauty of all the elements considered.

Sketching and drawing, at their best, reveal and confirm important things about ourselves, our values, our motives and our beliefs. Drawings are concrete statements about the artist's state of mind at a given point; they are records of thoughts and processes. However, great drawings and great art don't speak to the viewer's head, but to his heart and to his spirit. Can, or should, all drawings aspire to this? Of course not. But even a little thumbnail sketch can be beautiful and meaningful in fulfilling the purpose of its conception.