A Shock—and a Mystery

When I got outside the station and stood in the busy town street, I realized that I had no idea where to go and dreaded asking anyone the way to the prison. They might guess my secret, or even think I'd done something wrong. At last I timidly asked a lady, but she had no idea where the prison was. Then I asked a boy, about my age, who looked friendly. But he just laughed and asked me what I'd done and how many years I'd got.

It was well past one o'clock, and I was getting desperate. I'd never felt so completely alone. I looked around and saw an old lady selling flowers, so I went over to ask her.

“Can you tell me the way to the prison?” I whispered, feeling very embarrassed.

“Prison, love?” she asked. “That's not far from here. Take the number 8 bus. It'll take you right close. Then ask again.”

I ran and caught the next number 8 bus, but it was going the wrong way. I had to get off at the next stop, cross the road, and catch the next one going the right way. I realized I'd had no dinner and was desperately hungry.

The bus conductor told me where to get off, and I hurried toward the prison at last, my heart feeling as light as air. I'd done it! I'd arrived! I thought of Don's words. “I don't care what you did, Dad,” I whispered to myself. “I'm your girl, and I've come.”

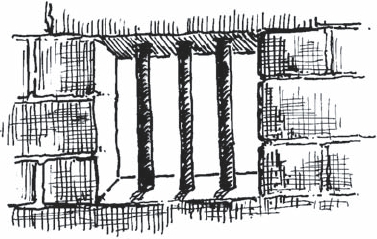

The entrance to the prison was an enormous door in a high stone wall surrounding a yard with buildings in it, and a smaller door with a grid set in it. The bell was too high for me to reach, so I knocked hard with my fists. No one answered at first, so I went on knocking, and my heart began to beat rather fast. Suppose visiting hours were over? I started kicking rather wildly, and at last the grid above my head opened and a voice said, “Hello?”

“Hello,” I answered, standing away from the door so that the person could see me. “I've come to see my father, Mr. Martin. He's been here about nine years, and I'm Lucy Martin, his daughter.”

“Sorry,” said a voice, “it's not visiting day today, and children aren't let in alone. Ask your mum to bring you next time.”

I could hardly believe my ears! I simply stared as the grid closed, and then I panicked. I ran at the door, kicking, hammering with my fists, and shouting at the top of my voice. “Don't go away! Please, please, don't go away. I haven't got a mother, and I've come alone. Oh, please, let me in! He's my father!”

I didn't notice the passersby forming into a little crowd to stare at me, but one lady, who thought, no doubt, that my father had just been locked up, tried to persuade me to come away. I pushed her aside and continued banging on the door, and in the end she rang the bell above my head and the grid opened again.

“Can someone speak to this little girl?” said the lady. “She seems very upset and quite alone.”

I heard footsteps going away across the courtyard, and the lady put her arm around my shivering shoulders trying to quiet me. Then we heard the sound of footsteps approaching, a key turned in a lock, and the little door set in the big door opened. A large man in a navy blue uniform stood looking down at me. “Now, now,” he said. “What's all this about?”

“It's my father.” I gulped. “He's here. I came all the way from Eastbury to see him and you won't let me come in, and I don't know where to go now, and I think I've missed the last train home, and oh please! I came all by myself, and I must see him. Please, please, please let me in!”

The officer looked down at me thoughtfully, and I'm sure I looked a most pitiful sight. “You'd better come inside,” he said kindly. “We'll see what can be done.”

I pressed through the open door without a backward look, and he led me into a small office just inside and pointed me to a chair.

“Now,” he said, “tell me all about it. What's your name and who's your dad?”

I told him everything, feeling sure he would not refuse me. He was a patient man. He listened right through to the end without interrupting once. “And I know he's a bad man,” I finished with a gulp, “or he wouldn't be here at all. But after all, he is my father, and I … I … well, we haven't seen each other for nine years and he wants me. He said so.”

The warden got up and sat down at the desk. He pulled out an enormous book. “John Martin,” he murmured, turning the pages. Then he sat for a long time gazing thoughtfully down at the book, as though he didn't know what to say next.

“Your dad wasn't a bad man,” he said at last. “We were all very fond of him … Nice chap, he was. But the trouble is … he's not here. He behaved so well, he got out early. Left here at the beginning of April.”

For a moment I sat rigid with shock as the real meaning of this dawned on me. Only one thing mattered. My father had been out of prison for over two months, and he'd never been near me or asked for me. It was all a terrible mistake. He didn't want me at all; I had no father. I crumpled up in the armchair and cried as though my heart would break.

The kind warden was quite upset but had no idea what to do. He lumbered off, scratching his head, and returned with some tea and cake and a comic and told me to cheer up as he was fetching a lady who'd help me. I tried to sip the tea, but my tears still flowed freely, and I cried until I could cry no more. Then a lady in a blue uniform arrived. She was a social worker called Miss Dixon. She acted as though she was quite used to dealing with brokenhearted children. She asked me a few questions and then said that what I needed was a meal and a good sleep, and she was going to phone my grandparents and ask them to come and fetch me. I worked myself into quite a state when she said that, and told her I had a return ticket and could easily get myself home. I didn't want an angry Gran coming to fetch me.

“Lucy, it won't be hard to find your father. There are records kept of all prisoners, and we should be able to trace him at once. But you must tell me your address, so he'll know where to find you.”

I fell into the trap at once. “Pheasant Cottage, Eastwood Estate, Eastbury,” I murmured, thinking that there was now no point in tracing my father. If he'd loved me, he'd have come to find me.

Miss Dixon went away and came back later saying she had phoned my grandparents and told them she was going to put me on the train back to Eastbury. “We had a long talk,” she said, “and there's nothing to be worried about. They will meet you at the station. They understand now about you wanting to see your father.”

“I don't want to see my father,” I muttered, “and I'm not worried.” Seeing I was about to cry again, she sensibly left me alone. I sat in silence looking at the comic until it was time to go to the station.

It was a miserable journey home, for I felt my brave adventure had failed completely. I sat dully staring out the window until the train stopped at Eastbury, and there were Gran and Grandpa hurrying forward to meet me. I noticed how white and old they looked.

I expected them to be really angry with me, but they weren't. I don't know what Miss Dixon had said to them, but Grandpa looked very miserable and kept blowing his nose, but he spoke cheerfully, and Gran had made a special cake for tea. It was all very strange.

Don arrived after tea. He seemed rather shy about meeting Gran, so he rang his bicycle bell at the gate until I saw him and rushed out with Shadow barking a welcome at my heels. Don's eyes were nearly popping out of his head with excited curiosity.

“Whatever happened?” he began. “Didn't you go? I got the bedding over to the stable right under my mum's nose, and she never guessed, and I went to the wood and hooted about a hundred times.”

“Yes, I did go,” I replied. “Come up the hill and I'll tell you all about it.”

He parked his bike inside the gate, and we climbed the hillside to a favorite place of mine. We settled down, and I told him every detail of my great adventure.

“Bet your Gran was mad at you!” said Don.

“No, she wasn't,” I replied slowly, stroking Shadow's ears. “She didn't say anything. I think Miss Dixon told her not to. But it was all for nothing, Don. He's been out over two months, and he hasn't come. I suppose he just didn't want to be bothered with me after all.”

Don shook his head slowly.

“He'll come,” he said. “Perhaps he's ill, or perhaps he wants to earn some money or find a home first or something. I'd better go—I've got loads of homework to do.”

We raced down the hill and he pedaled away, whistling. Happy Don, I thought to myself, speeding toward his beloved dad! I sighed and went into the house, glad that it was nearly bedtime.

Gran came up as usual, but she didn't tell me off. She kissed me good night and then lingered as though she wanted to say something but couldn't find the right words. Not like Gran at all!

“Lucy,” she said at last, “I'm sorry you couldn't tell us, but never mind about that now. But I want you to understand that if your father ever turns up, we will never stop him from seeing you. You are free to choose.”

She turned away and seemed to grope for the door, leaving me speechless and dismayed. What did it all mean? Had I been such a sly child that she did not want me anymore? Had I run after a love that never existed, only to lose the strong love I already possessed? My safe little world seemed to be crumbling all around me, and I panicked. “Gran, Gran,” I cried, and jumped out of bed and tiptoed downstairs to find them both. I had no idea what to say. I just had to get to them.

But on the bottom step I stopped as though turned to stone at a sound I had never heard before. Gran was crying, and between her sobs I heard her say in a broken voice, “Oh, Herbert, Herbert, whatever should we do without her?”

I turned and crept back upstairs. I had found my answer. I jumped into bed and fell deeply and peacefully asleep.